28,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Crowood

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

Toyota MR2 details the full start-to-finish history of Toyota's bestselling mid-engined sports car, from 1984 until 2007, when production ended. This new book covers all three generations of models: the first-generation AW11 - Car of the Year Japan, 1984-1985; second-generation SW20, with a new 2,0 litre 3S-GTE engine and the third-generation ZZW30/MR2 Roadster. With detailed specification guides, archive photos and beautiful new photography, this book is a must for every MR2 owner and sports car enthusiast. Covers the background to the MR2 - the 1973 oil crisis and Akio Yoshida's designs; suspension improvements to the Mk II, significantly improving handling; the MR2 in motorsport; special editions and Zagato's VM180. This complete history of Toyota MR2 includes detailed specifications guides and is beautifully illustrated with 260 colour and 36 black & white archive photographs.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 426

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Ähnliche

OTHER TITLES IN THE CROWOOD AUTOCLASSICS SERIES

AC COBRA Brian Laban

ALFA ROMEO 916 GTV AND SPIDER Robert Foskett

ALFA ROMEO SPIDER John Tipler

ASTON MARTIN DB4, DB5 & DB6 Jonathan Wood

ASTON MARTIN DB7 Andrew Noakes

ASTON MARTIN V8 William Presland

AUDI QUATTRO Laurence Meredith

AUSTIN HEALEY Graham Robson

BMW 5 SERIES James Taylor

BMW CLASSIC COUPÉS James Taylor

BMW M3 James Taylor

CITROEN DS SERIES John Pressnell

FERRARI 308, 328 and 348 Robert Foskett

FORD ESCORT RS Graham Robson

FROGEYE SPRITE John Baggott

JAGUAR E-TYPE Jonathan Wood

JAGUAR XK8 Graham Robson

JENSEN INTERCEPTOR John Tipler

JOWETT JAVELIN AND JUPITER Geoff McAuley & Edmund Nankivell

LAMBORGHINI COUNTACH Peter Dron

LAND ROVER DEFENDER, 90 AND 110 RANGE James Taylor

LOTUS ELAN Matthew Vale

MGA David G. Styles

MGB Brian Laban

MGF AND TF David Knowles

MG T-SERIES Graham Robson

MASERATI ROAD CARS John Price-Williams

MAZDA MX-5 Antony Ingram

MERCEDES-BENZ CARS OF THE 1990S James Taylor

MERCEDES-BENZ ‘FINTAIL’ MODELS Brian Long

MERCEDES-BENZ S-CLASS James Taylor

MERCEDES-BENZ W124 James Taylor

MERCEDES SL SERIES Andrew Noakes

MERCEDES W113 James Taylor

MORGAN 4-4 Michael Palmer

MORGAN THREE-WHEELER Peter Miller

PEUGEOT 205 Adam Sloman

RELIANT THREE-WHEELERS John Wilson-Hall

RILEY RM John Price-Williams

ROVER 75 AND MG ZT James Taylor

ROVER P5 & P5B James Taylor

SAAB 99 & 900 Lance Cole

SUBARU IMPREZA WRX AND WRX STI James Taylor

SUNBEAM ALPINE AND TIGER Graham Robson

TRIUMPH SPITFIRE & GT6 James Taylor

TRIUMPH TR7 David Knowles

VOLKSWAGEN GOLF GTI James Richardson

VOLVO P1800 David G. Styles

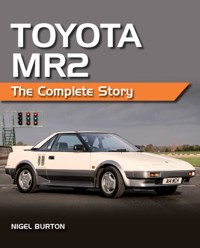

TOYOTA MR2

The Complete Story

NIGEL BURTON

First published in 2015 byThe Crowood Press LtdRamsbury, MarlboroughWiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book published 2015

© Nigel Burton 2015

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 84797 932 2

Acknowledgements

There are so many people who provided help for this book that it would be impossible to list them all. However, some deserve a special mention. I’d like to thank Jason S. Bell at the Toyota USA Archives for unseen photos and documents, PR manager Steve Coughlan in Australia, Alastair Moffitt at Toyota Motorsport and Erica Haddon, who trusted me with Toyota GB’s photographic resources. Peter Hunter of the Toyota Enthusiasts Club came up with some great photos of early MR2 designs and invaluable documents. Racing legend Dan Gurney, his assistant Kathy Weida and former CAR magazine editor Gavin Green gave generously of their time. Steve Bishop, editor of MR2 Only Magazine, gave me free rein to use images and information. Photographers Steve Brown (www.sbrownpix.com), Paul Kooyman, Keith Mulcahy, Dylan Alvarado and Miguel Gonzales gave permission to use their images and Tom Banks worked wonders on a photo shoot at Croft Circuit, near Darlington. Also, Bob Freitas and Pieter Lukassen were happy to answer dozens of questions about their rare cars. However, the biggest shout out of all goes to Michael Sheavills, who allowed me free use of his massive archive of cuttings, brochures and photographs. Without his help this project would have been immeasurably more difficult. Finally, thanks to my patient wife Jane and our two great children Jack and Mia.

Disclaimer

Every reasonable effort has been made to trace and credit illustration copyright holders. If you own the copyright to an image appearing in this book and have not been credited, please contact the publisher, who will be pleased to add a credit in any future edition.

CONTENTS

CHAPTER 1 ‘VALUE UNATTAINED IN ANY OTHER AUTOMOBILE …’

CHAPTER 2 AW11: THE START OF SOMETHING BIG

CHAPTER 3 SW20: ‘THE PASSION IS BACK …’

CHAPTER 4 MR-S: ’DRIVE YOUR DREAMS’

CHAPTER 5 RACING IMPROVES THE BREED

CHAPTER 6 TRANSFORMATIONS

CHAPTER 7 A NEW BEGINNING

REFERENCES

INDEX

CHAPTER ONE

‘VALUE UNATTAINED IN ANY OTHER AUTOMOBILE …’

The stevedores unpacking two small cars from the deck of the passenger liner President Cleveland at the Port of Long Beach, California, on 14 September 1957 almost certainly had no idea that they were making history. Nor did the modest crowd of journalists and civic dignitaries who gathered to watch the cars – one in Coronada Beige, the other resplendent in blue – as they were unloaded onto the dockside.

But for the Japanese officials present, the arrival of two Toyota Toyopet Crown sedans all the way from Yokohama harbour was a moment of immense importance: the first Japanese cars officially imported to the United States.

Earlier a group of thirty-five guests, including four Toyota executives, the Japanese consul general, the manager of the Bank of Tokyo, select pressmen and harbour officials, had gathered aboard the liner for a celebratory lunch. Afterwards they adjourned to the dockside for photos by the berth. No doubt, some of the photographers were more interested in Kyoko Otani, Japan’s entrant in that year’s Miss Universe beauty pageant, who hovered nervously clasping a bouquet of flowers while the cars were made ready.

History is made as the first Toyota – a Toyopet Crown – arrives in the United States. TOYOTA USA ARCHIVES

As the first vehicle was swung onto the dock, she glided forward and gently placed the bouquet on the bonnet: the first Toyota had officially touched down in the world’s biggest car market. (The guests were not to know, but the Crowns had been quietly unloaded in San Francisco a couple of days earlier to be washed and watered ahead of their formal unveiling.) The automobile industry would never be the same again.

The Toyopet Crown was designed and built by a new name in the international automobile world: Toyota of Japan. It was compact by American standards and the 1.5-litre 4-cylinder engine was comically small in a market where the best-selling car (the Ford Fairlane) came with either a 3.7-litre straight six or a 4.5-litre V8. However, Toyota was convinced that it would tap into the growing market for small cars. Instead of performance and speed, the Crown would sell on its value for money, four-door convenience and comfort.

To succeed, Toyota had to take on the Europeans. In the first five months of 1957 total imports exceeded $100 million. Volkswagen had a handsome lead with 40,139 cars, British importers came next on 34,141 and Renault was in third place with 11,587. Volvo accounted for 5,586 imports and Fiat just 1,127 vehicles.

The surge in small car sales encouraged Toyota executives to aim high. Seisi Kato, chairman of Toyota Motor Sales (TMS), remembered:

Exporting passenger cars to America, the ‘home’ of the passenger car; in those days it seemed like some wild dream come true.

During our test driving tour we introduced the Crown to various dealers, who all seemed impressed and spoke highly of the car’s market potential. From their responses our estimates were that 400 or 500 units could be sold a month; at that rate, we extrapolated that we could easily move a total of 10,000 units a year, and would just have to insist that Toyota Motor Company raise its production capacity to meet what we saw as clamorous demand.1

Toyota hoped to sell 500 Crowns a month in the US, but expectations were hopelessly optimistic. TOYOTA USA ARCHIVES

But the newsmen who watched the first cars arrive were sceptical. It had taken Volkswagen several years to achieve that kind of figure and the delicate-looking Toyopet Crown, despite its US-inspired styling, did not have the Beetle’s unique sales appeal.

Writing in the Indiana Gazette many years later, reporter Jim Bishop remembered his first meeting with a Toyopet: ‘My brother John … paid cash and drove it off an import dock. We crowded around it at the curb. [Our father] came out in his carpet slippers. His white head shook from side to side. “Did an engine come with that thing,” he said. “Or was it towed here?” ’2 His acerbic comment would prove to be uncannily accurate.

When the pressmen had got their stories and photos the Toyopets were checked by the customs examiner on the docks before being filled up and driven back to Los Angeles by Shotaro Kamiya, president of Toyota Motor Sales (TMS), and Shoji (George) Hattori, the head of TMS’s export division.

The following Monday the cars were driven to the Motor Vehicle Department where they were officially registered. A photographer from the Kyodo News Agency was on hand to record the moment for posterity and the pictures were sent back to Japan.

The happy photos, however, disguised major problems behind the scenes. A 927-mile test drive from San Francisco to Richmond, California, showed the little Toyopets to be out of their depth on America’s wide and smooth roads. Hattori sent an urgent message back to Japan:

Mr Kamiya and myself drove two Toyopets to Richmond, near Oakland, on October 15 and returned to Los Angeles on October 17. Mr Kamiya drove the RSL (beige color) and I drove the RSDL (blue color) [Crown Deluxe]. The California highway speed is 55mph (85km/h) at the present time, but there is now talk of lifting this maximum speed to 65mph (105km/h).

We did not have any trouble for the entire trip (not even a flat tire), but the RSL which was repaired prior to the trip (new camshaft etc) started to make the same noise again in the engine (just like a diesel) after 100 miles, but since we could not very well turn back, we continued with the journey.

There must be something wrong with the vehicle; therefore, now that the journey has ended, we are storing it until our Toyota service men come to the US in the future, since we cannot risk having it repaired over and over again for fear of ruining our reputation.

Toyota was so proud of its achievement in exporting cars to the USA that it marked every stage of their arrival. Here the first Crown receives its licence plates. TOYOTA USA ARCHIVES

In a follow-up letter, sent on 21 December 1957, Hattori said the exact cause of the engine malady could not be found and it would be shipped back to Japan for a full strip down.

The problem turned out to be the engine’s crankshaft, which had three main bearings when it really needed five. This design was fine in Japan, where the poor road system made high-speed driving impossible, but in the USA sustained cruising stressed the components to breaking point. At anything over 50mph (50km/h) the engine vibrated so badly the whole cabin shook. Pushed further, it broke. As Seisi Kato explained:

When the Crown was tried out on US freeways at 80mph, loud noises soon erupted and power dropped sharply. More trouble occurred before we had logged even 2,000 miles.

Although many people had praised the Crown as a ‘baby Cadillac’, for example, our engines, designed for the narrow-road, low-speed driving of Japan in those days, could not even begin to handle the performance and endurance demands placed upon them.3

One of the ill-fated Crowns makes its way through the Yosemite National Park. Wide-open freeways and steep hills would prove too much for the Toyopet’s small engine. TOYOTA USA ARCHIVES

Despite reservations among Toyota officials in the USA, Japan insisted on pressing ahead with sales and an office was duly opened in Hollywood. TOYOTA USA ARCHIVES

After the Crown debacle, Toyota’s beleaguered US importer had to rely on the Land Cruiser to keep the marque alive until new models could be put into production. Luckily for Toyota, the Land Cruiser was engineered to survive any conditions. TOYOTA USA ARCHIVES

Climbing hills was a particular trial. As the engine wheezed and gasped, first gear was usually required to reach the top. Crown drivers crawled up steep mountainsides at 15mph as trucks roared past, their drivers looking down with disdain at the funny little car from Japan.

Faced with this horrifying realization, and fearing terrible reputational damage, Kato said ‘our dreams sank out of sight like a ship with a giant hole in its bottom’. The sales team asked for permission to pull out of the USA but, to their surprise, the request was turned down flat. Help was on the way. Changes would be made. The Crown had to establish a bridgehead: failure was not an option.

Toyota tried to entice customers with a variety of purchase packages, including monthly instalments, but the Crown was still more expensive than European small car imports of the time. TOYOTA USA ARCHIVES

In the Beginning

When Japan ended 250 years of self-imposed isolation in 1868, the West was not slow to explore the possibilities, as modernization meant money-making opportunities for those countries willing to do business. First, however, the country’s infrastructure had to be updated. Japan had a haphazard road system, much of it built by feudal warlords during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.

The first recorded instance of a car being imported into Japan was a French Panhard–Levassor in 1898, which created nothing more than polite interest in Japanese society. Ten years later there were still fewer than 100 automobiles negotiating Tokyo streets crowded with thousands of rickshaws and bicycles.

The Toyota story, therefore, starts not with cars but with cotton. Sakichi Toyoda was the son of a carpenter. Despite having only a basic education, Toyoda had an inquiring mind. He loved to examine machines and explore ways of making them more efficient. Indeed, he asked his father to teach him carpentry so he could use his newly acquired knowledge to improve the loom his mother used. In 1891 Toyoda patented a new wooden hand-loom that improved textiles productivity by 40 per cent. Anxious to capitalize on this breakthrough, he started a business in Tokyo making and selling looms.

Although his hand-loom invention did not take off, he had better luck with a device for winding yarn. So much so, that his younger brother Heikichi came aboard as company sales manager.

The big breakthrough came when Sakichi designed a steam power-loom that could shut itself down automatically if a warp thread snapped. This meant a single operator could oversee several looms at once, saving time and, most importantly, money. Because the power-loom could make a decision for itself (when to stop), Toyoda coined the term ‘jidoka’, which means mechanization with a human touch, as opposed to a machine that simply moves under human supervision. At Toyota, jidoka has been refined into a five-step concept: a machine detects a problem; the problem disrupts the normal manufacturing process; the line is stopped; the manager fixes the problem; and improvements are incorporated into the workflow to make sure it does not happen again. This philosophy is at the core of everything Toyota does today.

With the domestic operation up and running, Toyoda cultivated a small export operation. Looms were sold abroad through Japan’s leading general trading company, Mitsui Bussan, to countries such as Manchuria, Korea and Taiwan. Toyoda looms had three major attractions: they were surprisingly reliable, easy to operate and, best of all, far cheaper than European imports.

However, the fortunes of Toyoda’s family firm waxed and waned, often in lock-step with Japanese military adventures, when demand for cotton soared. The First World War brought an unexpected bonus. Imports from Britain and America were interrupted and Toyoda stood ready to fill the gap in the market. When the war was over the Toyoda Cotton Spinning and Weaving Company had more than 1,000 power-looms and a similar number of employees. By 1920 more than 90 per cent of the looms made in Japan carried the Toyoda name.

Although he stuck doggedly with cotton weaving, Sakichi saw the potential of automobiles on a fact-finding tour of textile factories in the USA. In a prescient move, he urged his son, Kiichiro, who was then studying engineering at the Tokyo Imperial University, to pay close attention to the emerging car industry. Kiichiro would get his chance thanks to his father’s belief that Toyoda’s superior looms – in conjunction with better productivity – could overtake the British to become the world’s market leader.

In 1929 the company received an unexpected approach from England. Platt Brothers, based in Oldham and the largest manufacturer of textile machinery in the world, had bought 205 automated looms for one of its factories in India. Having seen them in action it was now keen to purchase Toyoda’s patent rights. Platts offered up a simple royalty payment scheme but Toyoda held out for a lump sum payment and, on Christmas Eve 1929, he signed the deal. In return for £100,000 Platts received the manufacturing rights for every market except China, the USA and, of course, Japan.

The British cash was not earmarked for the textile business, however. When Kiichiro travelled to Britain, seemingly to finalize the patent rights deal, he used his free time to get a good look at the UK’s motor industry. As the negotiations dragged on he took the opportunity to visit car factories, such as the giant Austin plant at Longbridge in Birmingham. Motor magnate Herbert Austin already had an eye on Japan but he missed a trick when young Kiichiro visited his impressive factory and the chance of a cooperative alliance was lost.

Having gained what knowledge he could, Kiichiro next pitched up in the USA, again under the pretext of patent discussions, and had a good look at America’s car factories.

When he arrived back home the following March he gathered together a team of the company’s best brains and told them he wanted to start work on an internal combustion engine with a view to using it in an automobile. The project would be funded by cash from the Platt Brothers deal.

At the time, Japan’s modest car industry was still dominated by major overseas players, in particular Ford and General Motors, which assembled knockdown kits imported from the USA. Indigenous car manufacturers were at least twenty years behind the foreigners and most were still hand-assembling automobiles in very small numbers (they managed a mere 436 vehicles in 1929). Alarmed by the success of the US importers, the Japanese government urged would-be car manufacturers to give it a go. Kiichiro had his green light.

The Toyoda Company already knew how to manufacture complex machinery to tight tolerances and, thanks to the profitable textiles business, it had a handy cash pile for research and development. In addition, Kiichiro was able to call on colleagues and experts he knew from his time at university. Sadly, his father would not be around to see the birth of Kiichiro’s first car: Sakichi Toyoda died on 30 October 1930.

Kiichiro had no plans to hand-build cars in small numbers. His ambitions lay elsewhere. He bought in the very best machine tools from Europe and the USA, built an electric furnace and set up facilities for chrome plating of bodywork parts. A steel mill ensured there would be no supply-side hiccups when production began. On 29 January 1934 the board of the Toyoda Automatic Loom Works gave its approval for a new steelmaking and automobile division.

The division’s first engine was a reverse engineered Chevrolet, which took months to study and develop. By summer 1935 the first Model A automobile was finished. The A1 also had some parts commonality with the Chevrolet, which would be handy in the event of a shortage of Japanese-made spares.

With government approval, the Toyoda auto business was able to tap into the country’s need for trucks. War was coming and the Japanese military was busy building up its forces. Toyoda simply took the Model Al’s engine and a Ford commercial chassis and fashioned a simple truck that could be cheaply made in large numbers. Despite disappointing early trials, when the drive train failed on the first test, the company soon had a truck to add to its portfolio.

Things were suddenly going Toyoda’s way. The Japanese government introduced strict import controls on the US car-makers and limited foreign factories to no more than 3,000 vehicles a year. Toyota, Isuzu and Datsun stood ready to fulfil domestic demand (they also received generous tax breaks).

Toyota is Born

In 1936, before the Model AA passenger car went on sale, the company changed its name from Toyoda to Toyota. Legend has it that Toyota was chosen because the word requires eight brush strokes in the Japanese Katakana alphabet rather than ten, and eight is considered to be a lucky number in Japan. It is also easier for Westerners to say, although it is debatable how important this was in 1936.

In the same year an assembly plant for trucks and cars was constructed close to the Toyoda loom works at Koromo. In August 1937 the Toyota Motor Co. was established with Kiichiro’s brother-in-law, Risaburo Toyoda, as its first president.

Another member of the family, his precocious nephew Eiji, was hired from university. He came to Kiichiro’s attention after designing a diesel engine for his thesis and was soon put to work at a research and development outpost near Tokyo.

The early Toyota vehicles were not without their problems and the company was often on shaky ground. It was saved by the intensification of the Second Sino-Japanese War, which saw all the trucks Toyota could make snapped up by the military. The Japanese government pressed Toyota to expand still further during the Second World War. During this time, Toyota also manufactured its first four-wheel-drive vehicle after the Army saw how effective the US Jeep was at traversing difficult terrain. The knowledge gained stood the company in good stead after the war and, arguably, saved the US import operation from total failure twelve years later.

The Japanese capitulation came just in time for Toyota. Allied documents show that, had the Japanese not surrendered, the Toyota construction plant in Aichi was scheduled for destruction by US bombers a week later.

The Allied occupation force quickly restarted truck building and by the following September the production lines were running again. The following January, Toyota had a small passenger car ready. The Toyopet was just what Japan needed: small, cheap and rugged. It did not matter that the engine displaced just 995cc because no one could drive very fast anyway, since the road network was ruined.

Shortly before the Model AA passenger car went on sale in 1936 Toyoda changed its name to Toyota – and never looked back. TOYOTA GB

By the mid-1960s Toyota was churning out models, like the Corona saloon, that were proving popular all over the world.

Company fortunes looked up again when another war loomed. This time it wasn’t the Japanese government but the US Department of Defense that placed a lucrative order for trucks during the Korean War.

Toyota recovered from its near-death experience and started to prosper, but Kiichiro did not live to see it make good on his dream of becoming a major player in the auto industry: he died of a stroke aged just fifty-seven.

Risaburo, too, was not in the best of health and the company’s future was vested in Eiji, who pressed ahead with production plans. In 1955 he watched proudly as the production lines stirred into life and the first Toyota Crown rolled out of the factory. Eiji drove the first model off the line to generous applause and the pop of flashbulbs.

The Crown, Toyota’s standard sedan, was designed to be a big-selling family car, while the Master was a commercial variant often used as a taxi. They both used the same 1.5-litre 4-cylinder engine, which had been introduced on the previous Toyopet Super model. The Crown was quickly followed by a Deluxe model, which came with such popular ‘extras’ as a heater and a radio as standard. These were the models chosen to spearhead Toyota’s overseas market assault, and so were the first two cars off the President Cleveland in September 1957.

Toyota Motor Sales USA and Toyota Motor Distributor were set up in February 1958, with their first office on Hollywood Boulevard. After the disastrous first year, when total sales were just 287 cars (and one Land Cruiser), it was decided to switch attention to the Land Cruiser while urgently needed improvements were made to the Crown. Not even Zsa Zsa Gabor, who posed with one at the Los Angeles Motor Show in 1959, could give the car a touch of glamour, despite the advertising claims that year that the Toyota Crown Custom offered ‘Value unattained in any other automobile’.

By 1960 Toyota sales had reached 821 vehicles (659 Crowns and 162 Land Cruisers). Four years later Land Cruiser sales had increased ten-fold, confirming that the decision to stay in the USA had been the right thing to do.

Eiji, who had moved to the USA to study market conditions, had high hopes for Toyota’s next passenger car, the Corona, because it had been designed with feedback from America in mind. The 1,897cc engine was bigger and more powerful and an automatic transmission was available. The first shipments reached Los Angeles in April 1965, by which time the Corona had been renamed the Tiara, and sales took off.

Celebrations on the Corolla production line in 1966. Cars like this helped make Toyota a serious international player by the end of the 1960s. TOYOTA GB

The smaller Corolla followed in October 1966 and delighted dealers had sold 12,000 examples by the end of the year. Toyota was now firmly established in the US market.

A Sporting Beginning

In April 1965 the Sports 800, Toyota’s first two-seater sports car, went on sale. The svelte S800, which was largely the work of Shozo Sato, who was on loan to Toyota from Datsun/Nissan, was a Japanese response to demand for cars like the MG Midget and the Triumph Spitfire. Built around a steel monocoque with double wishbones and torsion bars at the front, allied to a live axle suspended by semi-elliptic springs at the back, it was as good to drive as it was to look at.

Sadly, whatever chance it may have had in the US market, then just waking up to its love affair with small sports cars, was ruined by the choice of engine: a twin-cylinder flat twin with overhead valves and hydraulic tappets. This power plant, which was a hand-me-down from the Publica saloon, displaced a mere 790cc. Americans, long used to big block V8s, would have looked down on the S800 with contempt.

The Publica Convertible showed that Toyota could create stylish cars as well as utilitarian workhorses. The convertible was built by Central Motor Co., which would become the manufacturing home of all three generations of the MR2.

Toyota, however, had no plans to sell the S800 anywhere other than Japan where the modest engine dimensions and humdrum power output of just 45bhp (33.5kW) were far less of a problem. Because so much of the bodywork was fashioned from aluminium, including boot, doors and roof, the S800 weighed next to nothing, which meant it could almost crack the 100mph (160 km/h) mark.

Toyota even crafted a targa roof, which could be unclipped for fresh-air enjoyment. The S800 also came with such niceties as twin-speed windscreen wipers, screen washers, a map light, full instrumentation and, of course, a cigarette lighter.

The svelte S800 was the corporation’s first real sports car and entered production in 1965. Despite its looks, the performance from the underpowered engine was modest, but the S800 could certainly give small MGs and Triumphs a run for their money. TOYOTA GB

The S800 also proved surprisingly adept at racing, helping attract a new audience for the car and emphasizing the importance motor sport could play in marketing.

The car did wonders for the company’s motor sport image by competing successfully in a number of domestic endurance meetings. It cost ¥595,000 and more than 3,100 examples were built between 1965 and 1969.

TOYOTA S800

Toyota is still immensely proud of the S800’s place in its sporting firmament. Here an S800 takes pride of place in a line-up that includes a 2000GT and the GT 86 in the background. TOYOTA GB

The S800 was a surprising way of proving Toyota could do more than build mere bread-and-butter cars, but the company had something much more impressive on the starting block. In 1964 Jiro Kawano, the Toyota factory racing manager, pulled together a hand-picked team for Project 280A, a sports car good enough to take on the cream of the European elite.

The 2000GT was a stunner, a genuine high-performance sports coupé capable of trading blows with the best in Europe.

TOYOTA 2000GT

Although Kawano was a racing man, he knew Project 280A would have to be more than a stripped-out competition car if it was to be a sales success. So he told his team that the car would have to be genteel enough for everyday use while still providing the foundations for a successful GT-class racer. As it was never envisaged as a mass production model, high quality was more important than parts commonality with other Toyotas and ease of manufacture.

Designer Satoru Nozaki already had a good idea of what the car would look like. Some years earlier he had begun sketching designs for a GT car in the hope that, one day, he might have the opportunity to make the real thing. He had no idea that Toyota would give him a chance sooner rather than later.

Yamaha entered the fray after a disastrous dalliance with Nissan that ended abruptly when Nissan, the senior partner, lost its nerve and cancelled plans for a GT car to have been powered by a 4-cylinder Yamaha-designed engine. Determined to save face, Yamaha offered its coachbuilding services to arch rival Toyota and was amazed to discover a secret GT project already underway.

Thanks to a bit of help from Yamaha, the 2000GT had an excellent performance and its 2.0-litre 6-cylinder engine produced 150bhp (111kW), a figure that was then unheard of. TOYOTA GB

Yamaha supplied the aluminium cylinder head and pistons for the longitudinally mounted 6-cylinder engine, which used the all-iron block normally fitted to the MS41 Crown. Twin overhead cams were chain driven and the power plant was fed by a trio of twin-barrel Mikuni-Solex sidedraught carburettors. Maximum power was a claimed 150bhp (111kW) and the car was good for a top speed of 130mph (209km/h). Other items of note included the five-speed gearbox, a limited slip differential and all-round servo-assisted disc brakes (a first for a Japanese car).

The 2000GT was unveiled at the twelfth annual Tokyo Motor Show, in Harumi, in 1965. Sitting atop a circular platform and picked out by spotlights, it was an overnight sensation with the thousands of car fans jostling behind the barriers for a closer look.

The GT was daringly different, especially at the front where the twin driving lights, which sat behind plexiglass covers either side of the grille, were supplemented by a pair of pop-up lights (added to meet international regulations that specified a minimum height for headlamps). The bodywork was a feast for the eyes with its curvaceous front wings, ‘coke-bottle’ profile, curved windscreen and smoothly tapered boot lid.

The interior was every bit as special as the exterior. Thanks to expertise from Yamaha’s piano division, it featured a rosewood dashboard and a steering wheel and gearstick fashioned from mahogany.

The 2000GT was no stripped-out racer. The interior was lovingly crafted and the polished wood facia came together with help from experts at Yamaha’s piano division. TOYOTA GB

Pop-up headlights were only added to get the 2000GT through minimum headlight legislation, but they helped create the car’s distinctive face. Pop-up lights would, of course, figure later on the first two generations of MR2. TOYOTA GB

The 2000GT was the first Japanese GT to appear in a James Bond film, when a customized soft-top version featured in You Only Live Twice. TOYOTA USA ARCHIVES

Western journalists who attended the show could not wait to get behind the wheel: Road & Track said: ‘Nobody in his right mind could need, or want, for more in a road vehicle than the 2000GT’, while Motor Trend simply said: ‘It can hold the road with any iron cradling a power plant with double, or even triple, the displacement’. High praise indeed.

Famous owners included George Hamilton and British model Twiggy. Film star Paul Newman also expressed a desire to own one.

However, the car’s greatest claim to fame came when it appeared in the fifth James Bond film, You Only Live Twice. The GTs featured in this were convertibles specially converted for the film crew by the Toyopet Service Centre at Tsunashima. The ‘conversion’ was something of a Hollywood fake: the cars (there were two) had no roof and the hump behind the passenger compartment was a prop styled to look like a folded hood. The decision to commission the chop top allegedly came about because Sean Connery was too tall to fit comfortably in the standard GT.

Toyota successfully raced the 2000GT both at home and internationally. A race-prepared car is here seen at the Las Vegas Raceway in 1968. TOYOTA USA ARCHIVES

A racing 2000GT at Las Vegas in 1968. TOYOTA USA ARCHIVES

The Shelby GT competed for honours in the USA and, despite a horsepower deficit, finished on the podium several times. TOYOTA USA ARCHIVES

The 2000GT fulfilled Kawano’s hopes for motor sport success, too. Three cars developed by Shelby American Racing competed in the USA, taking three one-two finishes in their first season against tough competition. A 2000GT also won the Fuji 24-hour race in 1967 and set a string of speed records, including driving at 128mph (206km/h) for seventy-two hours.

Although the 2000GT was the toast of critics everywhere, commercial success eluded it. At launch Toyota had high hopes of selling a thousand cars a year, but the hefty price tag (more than an E-Type or a Porsche at the time), and buyers’ natural caution about a manufacturer with no history of making sports cars, meant sales were a major disappointment. Only 343 examples were built between 1966 and 1970.

By then Toyota had another sporting star, the Celica coupé, ready to go on sale, but the 2000GT had sown the seeds that would lead eventually to the creation of the world’s most successful mid-engined sports car: the MR2.

By the 1970s Toyota’s Celica had established itself as a cost-effective rival to the likes of the Ford Capri in Europe and was also making waves in the competition world.

Two of Toyota’s greatest small sports cars: the AW11 MR2 Mk I and, in the background, the S800. TOYOTA GB

CHAPTER TWO

AW11: THE START OF SOMETHING BIG

You feel this car, you live with this car, and you’ll love to drive it. The MR2 is fun. Pure fun. And that’s a promise.

MR2 sales brochure, March 1985

Major international motor shows are always eagerly anticipated by motoring enthusiasts, but the build-up to the 1983 Tokyo Motor Show was of a different order of magnitude. For months the car industry had been awash with rumours that the Japanese were preparing something truly special. Wounded by criticism that their cars were bland, characterless transportation devices for the masses and nothing more, the Japanese had set their designers and engineers loose on exciting new models and concepts. Tokyo ‘83 was to be the moment when Japan announced itself as a major player in the high-performance arena.

King of the world. The mid-engined SV3 was unveiled to massive crowds at the 1983 Tokyo Motor Show. TOYOTA GB

When the doors opened on 28 October four-wheel steering, variable valve timing, turbocharging, advanced materials, bleeding-edge aerodynamics, digital instrument displays and sophisticated four-wheel drive were everywhere.

Nissan had the sleek gas turbine-powered NX-21 coupé. Mazda proudly showed off the innovative MX-02, with four-wheel steering and variable valve. Mitsubishi had a 350bhp Starion. Honda displayed a bizarre three-wheeler and a turbocharged city car. Even Isuzu had a wedge-shaped sports car (the ill-fated Piazza).

Then there was Toyota.

The largest of the Japanese manufacturers, Toyota had left nothing to chance. Its stand was the biggest, the brightest and the loudest. Visitors – and there were tens of thousands – were assured that the 1980s would be ‘the age of Toyota’ and there were plenty of new models to back up such a bold claim.

The FX-1 sports concept was a technological tour de force powered by a 6-cylinder 24-valve twin-cam engine, two small intercooled turbochargers, variable valve timing camshafts and an induction control system. The second concept was the TAC-3, a ‘lifestyle’ small SUV that looked like a Lego brick Suzuki Vitara.

The FX-1 was certainly an impressive showcase but that is all it was: a four-wheel rolling laboratory for various Toyota technologies. It was never going to go into production. Neither, despite being based on the running gear of a Tercel 4WD, would the TAC-3 see the interior of a dealer showroom, although it probably helped inspire the Toyota RAV4 a decade later.

All the Tokyo concepts suffered the same fate. With national honour upheld, and European rivals well and truly put in their place, the dream machines disappeared, never to be seen again.

All but one, that is.

The third ‘concept’ on Toyota’s Tokyo Show stand, a sports car called the SV-3, was actually very close to production reality. The SV-3 did not have a gas turbine engine, active suspension or four-wheel steering, but it did have a mid-engine layout and Toyota was deadly serious about building it. The SV-3 was destined to be Japan’s first production mid-engined car.

It took centre stage on a revolving show stand at the centre of the Toyota display, which had the added bonus of keeping the prototype well out of reach of inquisitive fingers. The base of the stand was packed with television monitors playing video footage of the SV-3 during testing weaving through traffic cones and skimming around a test track at full speed. Others displayed cutaways of the chassis and the impressive mid-engine packaging.

The SV-3’s wedge shape and sharp lines recalled the Bertone-styled Fiat X1/9, but Toyota’s new twin-cam 4-cylinder engine easily had the measure of the X1/9’s asthmatic old 1.5-litre power plant. The Toyota had been carefully honed by a team of enthusiastic designers and engineers who had worked long hours, sometimes in their own time, to ensure it was truly special. There were even rumours of Lotus involvement in the project.

Its upper body was finished in white with the lower third painted a light grey. The two colours were separated by a thin yellow pinstripe rubbing strip, which ran in a continuous line around the car and through the plastic bumpers. A modest spoiler sat on the boot and, although it was not a full convertible, the show car did have a removable roof panel.

The SV-3’s wedge shape and sharp lines were reminiscent of the Bertone-styled Fiat X1/9, but the engineering was all Toyota. TOYOTA JAPAN

The cabin was equally impressive with hip-hugging sports seats, a cosy cockpit, a tiny gear stick mounted high on the transmission tunnel and a full set of instruments. The only bizarre note was a pair of headrest-mounted intercoms: what was Toyota thinking?

Visitors to the show were impressed. Crowds flocked to the Toyota stand to see it for themselves and take pictures. Prospective buyers who asked after its availability were told that the SV-3 would go on sale the following year, in 1984.

This was no idle promise. The SV-3 had endured a somewhat convoluted birth, but the car shown at Tokyo was within an ace of being fully production ready. Just a few months earlier, it had been putting in fast laps of the Zolder circuit in the Netherlands under the watchful gaze of Toyota engineers who were delighted by its performance.

With a couple of modest tweaks, and a last minute change of name, the MR2 was almost ready.

1976: The Project Begins

The car that would become the SV-3 started life in 1976 as a fairly nebulous concept for a small, economical car for young drivers. It did not start life, though, as an out-and-out sports car. Although it needed to be reliable and cheap to buy, the overriding priority was that it should be fun to drive.

Chief development engineer Akio Yoshida, a Toyota veteran with eighteen years of experience, was the man chosen to head the project, working with a carefully selected team of engineers and designers. He had spent time in Los Angeles and during weekend excursions he noticed dozens of small sports cars, mostly MGs and Triumphs, but some times an Alfa Spider or even a Lotus Elan, using the same roads. Even though many were relics of the 1960s, he could see that their owners still took pride in how they looked. As he recalled:

Although it started life as a small economical car for young drivers, the project soon took on the proportions of a sports car.

While working in Los Angeles, I commuted to the office by car because I thought it would give me the ‘feeling’ of how a car is used in everyday life. I drove typical American cars of various sizes and types and evaluated the merits and problems of American cars from which Toyota should learn and improve upon.

On the weekends, I tried to drive long distances to experience how the cars were used for recreation. These experiences made me see the need for a quick, manoeuvrable car with good acceleration. For commuting, a twoseater would be sufficient. And if it also has good fuel economy, that would be great. At that time, I still had not come up with the image of the mid-engine car.1

Yoshida’s thinking was supported by feedback from Toyota’s American arm, which was lobbying hard for a cheap sports car.

However, as the team racked their brains to come up with fresh ideas, the project was dealt a blow by external events when international economic upheaval, which had far-reaching implications, rocked the automobile industry.

In the 1960s and early 1970s Toyota enjoyed a period of unparalleled rapid growth, but by the mid-1970s things were not looking so rosy. The 1973 oil crisis, and subsequent strangulation of oil supplies from the Middle East, had thrown the global economy into reverse. Every car manufacturer was feeling the heat, particularly in America, the world’s biggest car market, where sales had stagnated. As pump prices soared President Eiji Toyoda summed up the sombre mood: ‘In the past we tended to approach the solutions to all problems through the lens of expanding volume, but in the future we need to transform our thinking … so we can maintain operations without relying on volume.’2

Toyota’s response was to pour more resources into research and development. Teams were set up to examine new technologies like electronic engine control systems, new powertrains, miniaturization and the use of lightweight materials like high tensile steels, plastics and resins. Groups were also set up to examine every process, spare part and production line for possible savings. This work, which was carried out in the second half of the 1970s, laid the foundations for Toyota’s incredible success in the 1990s and beyond.

However, in the short term, with investment funds tight, management had to decide which projects took priority. Topping the list was Toyota’s first front-wheel-drive design, the Tercel, which was crucial to reinvigorating the company’s short-term fortunes.

Then there was a new Corolla, the model that was the bedrock of Toyota’s worldwide success. By 1976 work was already in motion on the fourth generation model and nothing could be allowed to compromise the company’s bestseller (6.2 million and counting by the end of 1977).

With development of the new front-wheel drive Camry/Vista also underway, less important projects were put on the backburner. The small twoseater concept could easily have been cancelled altogether but, thanks to Akio Yoshida’s determination, it survived.

By 1979, when the first fruits of Toyota’s technology sprint began to arrive and sales took off again, the project was back on and the team was given the green light to create a pre-production prototype. But what kind of car should it be?

The obvious choice was a small front-engine, rear-wheel drive (RWD) two-seater, rather like the MGs and Triumphs Yoshida had admired during his stay in North America. Front-wheel drive was not thought to be suitable for a two-seat sports car and, anyway, a front-drive Corolla GTi hot hatch was already being readied for production with a tentative launch date in 1984, the same year the sports car was due to go on sale.

There was a third way, however. The Fiat X1/9 had been designed by Bertone, the legendary Italian styling house behind the Lamborghini Miura, the Espada and the Ferrari 308. Although a common lament was that it needed more power (even after the 128 engine was dumped for a more powerful 1.5), in every other respect the X1/9 epitomized everything Toyota hoped to achieve with its forthcoming two-seater. The Lancia Montecarlo, which had begun life at Fiat as a larger companion to the X1/9, also showed what was possible with a mid-engined chassis powered by a larger twin-cam engine.

The MR2’s most obvious rival was the Fiat X1/9 although, after a promising start, the Italian car had been rather neglected by its parent.

FIAT X1/9

Before the X1/9 Fiat already had a rich tradition of making small sports cars for the masses, unlike Toyota, so it seemed perfectly natural for the company to take the new 128 and use it as the basis for a compact two-seater sports car.

The X1/9 was conceived as a replacement for the ageing 850 Spyder, which had been a huge success in the US market. The idea was handed over to coachbuilder Bertone, which already had some experience of mid-engined cars after working with Lamborghini. On seeing the proposal, Fiat boss Giovanni Agnelli gave his approval and a concept, dubbed the Runabout, was shown at the 1969 Turin show.

Bertone made the most of the mid-engined design by giving the X1/9 two storage areas for luggage, one at the front where the engine would normally be and one at the back behind the power plant (Toyota would use the same layout for the MR2). A frontmounted radiator helped the 1290cc 4-cylinder engine keep its cool in the Italian summer.

The X1/9 was launched in November 1972 (although right-hand-drive versions did not arrive in the UK until late 1976) and was a huge success.

In typical European fashion, however, the X1/9 was rather neglected thereafter. The biggest change came in 1978 when the 1300 engine was replaced by a 1500 from the Ritmo (Strada to UK and US drivers), which gave a useful performance boost. Three years later Fiat handed over responsibility for production and sales to Bertone, which attempted to maintain interest with a series of special editions.

To combat the MR2’s arrival in Europe, Bertone initially introduced a high-specification VS (limited edition) version. When that failed to do the trick, a cheaper permanent addition to the range was introduced from February 1986. Both variants cost less than the Toyota, but the big difference in performance between the two made the MR2 the more popular choice among enthusiasts.

The X1/9 was finally withdrawn in 1989 after remaining largely unchanged for seventeen years, unprecedented for a small sports car.

Other cars studied by the team during the design phase included the French Matra Murena, the Ferrari 308 GTB and the Lotus Esprit. Astonishingly, the engineers were most impressed by the Matra. Its good showing was a surprise because it was based on the rather dreary Simca 1100 hatchback, cleverly rejigged into a mid-engined layout by adding stylish plastic panels to the steel chassis. The Murena did have bespoke MacPherson suspension at the rear, but its 1.6-litre 4-cylinder engine was no Ferrari chaser. Later Murenas were available with the Talbot Tagora’s 2.2-litre engine but, even then, performance was leisurely at best because it only had 118bhp (88kW) with which to push along 2,277lb (1,033kg). The Murena’s one true innovation, its three abreast seating, was out of the question on a small Toyota because such a layout would make it too wide.

Nevertheless, Yoshida’s team felt the Matra was an interesting experiment in creating something special from an everyday car:

We [had] received information from Toyota in America suggesting a potential market for an affordable sports car, so the concept of the compact mid-engine twoseater with good economy, performance and practicality was born. The realization of the concept was presented in the form of a prototype production project.3

If the new car was to meet the aim of creating something that was truly fun to drive, with compact dimensions and attractive looks, then a mid-mounted engine layout was the way to go. Although the home market for two-seaters was small, worldwide potential (particularly in North America) looked far more promising.

Having carefully considered the arguments, the Toyota board agreed. In signing off the project, president Eiji Toyoda was writing a new chapter in the company’s history: the new car would be the first Japanese mass-produced, mid-engined car.

As the engineering teams set to work, the designers had to come up with an appealing ‘look’ for the new model that would wrap around the small mid-engined configuration without making access, particularly to the engine, too much of a headache. This was no easy task.

When Toyota’s engineers examined the competition they were especially impressed by the little-known Matra Murena.

This early concept art looks almost American in its execution.

Seiichi Yamauchi took his inspiration from the Japanese katana sword, characterized by its elegance.

The car’s proportions are clearly visible in these artists’ concepts.

The original prototype was an unhappy melange of Triumph TR7 nose and Fiat X1/9 boot. It was, almost literally, a car crash of a design that looked like a distillation of general sports car thinking in the late 1970s, but it lacked a personality of its own.