18,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Crowood

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

This practical book is aimed at all greyhound enthusiasts and will be of help to the more experienced professional trainer as well as the novice handler. The physical stresses of racing mean that every greyhound will, at some point, sustain some form of injury and it is therefore essential that the greyhound handler has some knowledge of injuries. Accordingly, the author places a strong emphasis on injury prevention, diagnosis, treatment and rehabilitation. Contents include: Choosing your first dog; The fundamental aspects of training; Kennelling; Breeding, rearing and training puppies; Exercising, the training routine and race preparation; Feeding; Examining your dog, minor ailments and serious illnesses; Foot problems; Injury rehabilitation and the skill of massage; Retired greyhounds. This wide-ranging and practical book is aimed at all greyhound enthusiasts including those who train and race them, care for them or own them as pets. Fully illustrated with 69 colour photographs and 20 drawings.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 322

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Ähnliche

TRAINING AND RACING THE

Greyhound

Darren Morris

THE CROWOOD PRESS

First published in 2009 by

The Crowood Press Ltd

Ramsbury, Marlborough

Wiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book first published in 2014

© Darren Morris 2009

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 84797 966 7

Photographic acknowledgement

The action photos in this book were supplied by Steve Nash. Steve has specialized in greyhound racing photography since buying his own greyhounds to race at the old Wembley Stadium back in 1984 and has been Racing Post’s greyhound photographer since the paper’s launch in 1986. His work has appeared internationally in numerous publications, books, advertising campaigns, websites and other media, and can be viewed at www.steve-nash.co.uk.

Disclaimer

The author and the publisher do not accept any responsibility in any manner whatsoever for any error or omission, nor any loss, damage, injury, or liability of any kind incurred as a result of the use of any of the information contained in this book, or reliance upon it. This book is not in any way intended to replace, or sidestep, the veterinary surgeon and, if in doubt about any aspect of their dog’s health, readers should seek professional advice from a qualified veterinarian.

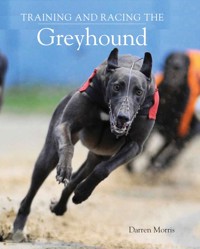

Cover: Ninja Jamie winning Derby Plate heats, Wimbledon Stadium, 24 May 2008. (© Steve Nash Photography)

Contents

Acknowledgements

Preface

1 The Greyhound and Greyhound Racing

2 Basic Care and Training

3 Breeding and Early Training

4 Feeding

5 The Training Routine and Race Preparation

6 The Anatomy of the Greyhound

7 General Care of the Greyhound

8 The Ailing Greyhound

9 The Injuries Incurred by the Racing Greyhound

10 Foot Problems

11 Injury Rehabilitation and Massage

12 The Older Greyhound

13 Buying and Selling a Greyhound

Glossary

Index

Acknowledgements

I have worked in the greyhound industry for over twenty years and during this time have benefited from the knowledge and expertise passed on to me by many of those with whom I have worked. Without their input I would never have gained the information that has enabled me to write this book.

The first trainer I worked for was the late Gerald Lilley; he was the only one who would give me a job when I was a small boy of thirteen. I then worked for Kevin Rushworth, Terry Townsend and George Curtis, who further extended my knowledge. Throughout my involvement with greyhounds I have always had a very keen interest in injuries, and I learned a great deal from the following vets and specialists: Plunkett Devlin, Ron Bradburn, Chris Backhouse, George Drake, Francis Allen, John Jenkins and Carol Patterson.

I would especially like to thank Laura Thorpe for her help with the photography, and Jackie and John Teal for their help over the last decade.

I would also like to thank my partner, Sophie, who strongly encouraged me to write this book, and who has shown incredible patience during the countless hours I have spent writing it.

Preface

The greyhound is a unique breed of dog; it has been around for thousands of years and has accompanied man as both hunter and companion. It is one of the fastest land mammals ever to grace our planet, and its speed has been used to hunt quarry around the globe. It has a laid back nature and loves attention, and this love is often returned unconditionally. Over the last century it has become better known as a racing dog, and it competes in races in many countries.

This book is aimed at the greyhound enthusiast, and contains information and advice on many different subjects, such as buying a dog to preparing a greyhound for a race; it covers several aspects of both racing and training. Issues such as feeding, anatomy and general care are all discussed to try and give the handler a closer look at this fascinating breed. At its heart is an in-depth chapter on injury diagnosis, and the accompanying problems that injuries may cause. Due to the physical stresses of racing and coursing, every greyhound will at some point sustain a fairly serious injury – indeed, minor injuries of some degree can be sustained every time the dog sets a paw on the track.

The book also takes a look at some of the serious and some of the not so serious complaints that a handler may need to diagnose. Unfortunately, it is often only in the later stages of injury or illness that a greyhound is actually taken to a veterinarian for treatment, when in some cases early diagnosis can be critical to the health of the dog. For this reason it is important that the trainer works in close conjunction with his veterinarian.

Whether you’re a novice handler or a professional trainer of long standing, I am sure that Training and Racing the Greyhound has something to offer.

Lenson Joker racing at Wimbledon in 2008. This dog was voted 2008 Greyhound of the Year, the sport’s highest honour. (© Steve Nash Photography)

CHAPTER ONE

The Greyhound and Greyhound Racing

ABOUT THE GREYHOUND

The greyhound is a medium to large breed of dog and can vary a great deal in both size and shape. At its smallest a bitch may weigh as little as 20kg (44lb), but a male dog may well tip the scales at anything up to 40kg (88lb). It can also be contrasting in shape, as some are tall and lean while others are short and stocky. But while size and shape can differ, its general characteristics are always easily distinguishable from any other breed, typically the long snout, deep chest, well tucked up abdomen, and the heavy musculature covering its frame. In its prime the greyhound should be well muscled and should look like an athlete in every sense of the word. Its strong, solid and pronounced musculature should be covered by very little fat, giving that rippling effect as it moves.

The greyhound’s coat is short, and because of this it is easily manageable: grooming, bathing and massaging can be readily accomplished even by the novice. Most pedigree breeds come in one or two colours; however, the greyhound is different and comes in a wide variety of markings and colours. First there is the plain dog that is a straight colour such as black, blue, brindle, fawn and occasionally all white or chocolate – though for the greyhound even these straight colours can have a variation, such as red fawn, blue fawn, blue brindle, silver brindle, light brindle and dark brindle. Second there is the coloured dog, which is basically white but with patches covering parts of it; the easiest way to describe it is to compare it to the markings of a dairy cow. The patches are most commonly black or fawn in colour, but blue and brindle patches are still plentiful.

A white and brindle dog; notice that the white is greater than the brindle.

As a rule the greyhound is placid and laid back in nature, and almost never shows any sign of aggression, especially towards a human; it is often happy to sleep for most of the day, as it loves nothing more than to chill out and relax. However, it must be understood that the greyhound is also a hunter by nature, and if provoked can get excited very quickly, especially in a kennel or pack environment. It is both strong and highly mobile, so it is important that the handler keeps his wits about him at all times; if you are caught off your guard, a greyhound can easily pull you off your feet.

As the greyhound has been bred to hunt, the handler must understand that small animals moving quickly in the line of sight are very likely to be chased. If your greyhound is being exercised with other dogs, then it is important to take precautions; for instance, always keep a dog muzzled, and never exercise more dogs than you can control.

Although the greyhound is not considered to be very intelligent when compared to other breeds of dog, it makes up for it in other ways. It has an abundance of speed and sheer enthusiasm when asked to perform a task. Its body is toned and conditioned like no other breed, allowing it to reach speeds in excess of 64km/h (40mph); this makes it one of the fastest land mammals on earth. It also loves attention, and will equally happily give its affection to everyone and anyone it comes into contact with. It rarely shows total loyalty to one person or master.

Altogether the greyhound is a remarkable animal, which is why many different breeds of dog are crossed with it, the idea being to breed in a little more intelligence to accompany the speed. These cross-bred dogs are known as lurchers, and are themselves remarkable animals.

A LITTLE GREYHOUND HISTORY

The greyhound is the most ancient breed of dog. Paintings and murals have been found dating back well over 4,000 years; it has even been noted that a mummified dog with the attributes of a greyhound was found in a tomb dating back to 6000BC. The greyhound is the only dog to be mentioned in the Bible.

Over the centuries there have been many cultures that have truly admired our beloved greyhound, such as the Egyptians, the Persians and the Greeks. The Egyptians held it in the utmost respect and gave it almost god-like status; it was kept both as a pet and a hunter, but many of the kings and high hierarchy would pitch their greyhounds against each other in races chasing wild game – to have a fast hound may well have brought favour in the king’s eyes. Many Egyptians have greyhounds portrayed in their tombs, and when you consider that only things of significance were selected for portrayal here, then it must be assumed that the greyhound was regarded as highly important.

Throughout ancient history the Greeks and the Romans are both associated with the greyhound; even many of the Greek gods are portrayed with one. The Romans loved their greyhounds too, and are known to have enjoyed coursing; however, they often ran their dogs for the thrill of the chase alone, and not for hunting for food.

Like the Egyptians, the Arabians held the greyhound in very high esteem, and it became much sought after; it was the only dog permitted to ride with them on their camels, and also to be allowed into their tents.

In the Middle Ages the greyhound became almost extinct during times of famine; it was rescued from this almost certain fate by clergymen. It was then cared for and bred by the nobility; in the tenth century King Howel declared that killing a greyhound would be punishable by death. During these times most dogs were considered of no value and almost treated as vermin; however, by contrast the greyhound was seen as elegant and noble.

A greyhound at play.

In the 1500s Queen Elizabeth I initiated the first formal rules of hare coursing, and these rules were still in use when the first official coursing club was set up in 1776 at Swaffham.

In the nineteenth century the greyhound was still favoured among the nobility and royalty, with greyhound coursing becoming even more popular; the Waterloo Cup was founded in 1837. It was during this period that the greyhound was imported to the United States to help in the control of the jack rabbit, which was wreaking havoc in the crop fields.

In July 1926 the first ever greyhound race meeting was held at Belle Vue in Manchester, and in June 1927 the great White City in London opened its doors for the first time; soon it was said to be attracting an estimated 100,000 people per meeting. Greyhound racing was born.

GREYHOUND RACING

Greyhound racing was brought to England by the American Charles Munn, who had the overseas rights to the mechanical lure or hare. The first track was opened at Belle Vue, and it made so much money that further tracks at Harringay and White City were soon being planned.

With the sport becoming increasingly popular and the potential for malpractice becoming ever greater, the promoters of many of the tracks held a meeting at Wembley to discuss the founding of a nationally controlled organization. It was agreed unanimously that a greyhound club along the lines of the horse racing jockey club should be set up. The motion was passed, and the club was formed on 23 April 1928. At this point in time forty-three tracks agreed to be regulated under the legislation of the newly founded club, known as the National Greyhound Racing Club, or the NGRC.

Greyhound racing continued to flourish, and became extremely popular with the working class, who found the urban locations and the evening race cards convenient for their life-style. Owners and patrons from all walks of life came racing, and the sport became very popular among gamblers; even today gambling is arguably the backbone of the greyhound racing industry.

Greyhound racing reached its peak in attendances shortly after World War II, but since then it has suffered a downward spiral largely because of the legalisation of off-course betting (betting shops), televised sports coverage, and most recently the introduction of Internet betting. All these facilities make it far easier for the punter to place bets to his heart’s content without ever leaving the comfort of his own home. However, greyhound racing has always had strong grass roots and is still popular throughout the world in all walks of life. It is the second largest spectator sport in England, with tracks spread over the length and breadth of the country. Because of its popularity, racing takes place on seven days a week, with meetings being run morning, noon and night to cope with the heavy demand of both punters and bookmakers.

Ballymac Touser, Trap 4 (right of shot), leading Da Vinci Smiler (Trap 5, left), Peterborough Stadium, 19 July 2008. (© Steve Nash Photography)

Ballybeg Honcho leading at the first bend in the Champions Night Puppy heats, Romford Stadium, in July 2002. (© Steve Nash Photography)

Greyhound racing also takes place around the world with Ireland, Australia and America being leading countries in the greyhound industry.

In England, Scotland and Wales there are tracks governed by the NGRC (National Greyhound Racing Club), but as well as these there are also independent tracks run under their own rules and regulations. It is somewhat similar to horse racing, where there are professional trainers who run under Jockey Club rules at recognized race tracks, and then point to point meetings run under the auspices of the local Hunt and held at local courses.

Racing under the NGRC is run under strict rules, and the dogs’ welfare is closely scrutinized. The trainers will have their kennels checked on a yearly basis by a designated racing steward to make sure they are up to standard. Each and every trainer, kennel hand, track official and member of track staff will have to have a licence to operate or work at an NGRC track. A veterinary surgeon will be present at every race meeting to check each dog for injury or illness, and the dogs are regularly drug tested to prevent trainers from using illegal substances.

On the independent circuit each track is run by its own set of rules, which vary from one track to another. A trainer needs no official licence, and indeed anyone who owns a greyhound can turn up and race his dog. These tracks rarely have veterinary supervision on site, and drug testing is never undertaken. Over the years these tracks have been exceptionally popular, and until recently there have been dozens of them spread over the length and breadth of the country. However, over the last twenty years the price of building land has been high, and sadly many of them have been sold off for building development.

There are two types of race for a greyhound to compete in, depending on its ability: graded events, which are races where six dogs of equal ability are pitched against each other; and open events, where any dog may enter – though these races are generally aimed at the better class of dog. Each track also has a racing manager or management team, responsible for its day-to-day running.

The Racing Manager

The racing manager is also in charge of the day-to-day racing programme; it is therefore his job to assess the greyhounds competing at his track, and to grade or rank them accordingly. When any dog has a trial or race at a track it is timed by an electronic timing system, and this enables the racing manager to assess accurately how fast each greyhound is. He must also place each greyhound in the trap he thinks will suit it best, according to its trials or races.

When the manager is happy with a greyhound’s trial or trials, it will then be made available for the racing strength, and it is from this criterion that he selects the dogs to make up each race. It is ultimately his aim to place six dogs of equal ability into a race, and get them to finish as close together as possible at the winning line.

Trials

When a new greyhound is taken to a track it must compete in three trial runs so that the racing manager can assess its ability. A trial is basically a timed run around the track, and the dog can then be graded or placed into a race with dogs of a similar speed, judged according to the times they achieved in their trials. When a greyhound has been off the track with an injury, the racing manager will often require that it also has a trial run before it can be made available to run in a race again.

While in the majority of trial runs three greyhounds will take part, in the case of a dog having its first run at a new track, most trainers prefer to give a solo trial (with just the one dog). This is because many of the tracks, especially those in England, are totally different in size and shape, and if a dog has a solo run it can have a good look at the track before it competes with other dogs. A solo trial is also often preferable when a greyhound is having its first trial back after being injured, because it then has the chance to have a clean run without being bumped about by others.

Graded Races

Once a greyhound has had its three grading trials, and provided it is fast enough to compete, then it will be allowed on to the racing strength or quota. It is from this racing strength that the racing manager compiles his races, which usually range over about ten different levels. The track and its racing strength will largely influence how many levels or grades of racing it has. These levels are usually numbered from one upwards, and the lower the number, the better the class of dog; grade one therefore always includes the best dogs on the track.

In graded racing there are three different distances at each track: sprint races, standard races, and long distance races. Standard races are generally around 500m, and make up a large portion of the greyhound races that take place in England. Sprint races and longdistance races are often added to the racing card to supply a bit of variety.

Handicap Racing

Handicap racing is when dogs of different levels of ability are all placed into the same graded race. Each greyhound has its own starting trap and receives a designated number of metres’ start from the ‘scratch’ dog. Thus the best dog in the race runs from scratch, or the furthest trap back, then each trap is set at a distance in metres, as decided by the racing manager. For example:

Trap 1:

Billy the Kid

Receives 13m

Trap 2:

Sam the Baker

Receives 10m

Trap 3:

Mr Fish

Receives 8m

Trap 4:

Honey Bunny

Receives 6m

Trap 5:

Treacle Tart

Receives 4m

Trap 6:

Roach’s Pride

Scratch

On the independent circuit most of the racing is run in this way, the handicap form. Some greyhounds, especially puppies, gain a serious advantage at being put at the front of a handicap, because they then have a good chance of seeing the hare or lure without getting bumped and tipped about. It must also be appreciated that some greyhounds don’t chase the hare properly, and these dogs often benefit from chasing poorer quality dogs. In normal flat races they may well hit the lead too early and will then wait for another dog to run alongside, whereas in the handicap race they often have dogs way out in front to chase, which means they don’t catch them until near the finish, so they actually run a much better race.

Open Races

In open races the best dogs race at various tracks up and down the country. Unlike in graded events where a greyhound will race at the same track on a weekly basis, the open race dog will travel from track to track, depending on where the open races are taking place. Generally a track will advertise an open race or competition, the trainer will enter his greyhound, and the racing manager will then pick the best six greyhounds out of those that have been entered to make up the race.

As well as single open races there are often open competitions where heats, quarter finals, semi-finals and a final may well be run. These events are often of great financial and prestigious benefit to the winning trainer and dog.

Open races are like graded racing in that the races involve a broad spectrum of distances. As well as sprinting, standard and long-distance races, there are also marathon races, which are anything up to 1,000m.

Types of Hare

In greyhound racing the dogs chase a mechanical hare that runs around the inside or the outside of the track. In the early days of racing the majority of tracks ran with a hare on the inner circumference of the track; however, as time has moved on, many of the tracks have changed to a hare system where the hare runs around the outer edge of the race circuit.

There are two types of hare system in use today: first, the Sumner hare system, which runs above the ground on a rail; the hare itself is situated on a short metal arm, usually on the inside of the track. Secondly there is the McGhee hare that runs on a rail situated in the ground; this system is always on the outside of the track. The McGhee hare runs along the ground in a more life-like manner.

Interestingly, some greyhounds will only chase one type of hare system. If a puppy is schooled or has learnt to run on one type of hare system it will sometimes not chase the other type. Some dogs will chase one type of hare 100 per cent, but when put behind the other hare they may well not chase it properly. This is often seen in greyhounds that play and fight with the leading dog of the race; they tend to run with the other dogs, and don’t chase the hare.

Greyhound Coursing

Greyhound coursing has taken place for thousands of years, but the Hunting Act, passed by Parliament in 2004, made it illegal to hunt with dogs; this included fox hunting, the hunting of deer, hares and mink, and organized hare coursing. The Act came into operation in England and Wales in February 2005. Greyhound coursing involved two greyhounds being pitched against live quarry in an open field designated specifically for this purpose. Hare coursing was not about killing hares, but about determining which dogs exhibited the most agility and the highest speed. Thus two dogs would compete against each other in a chase after live quarry, and the dog with the most points proceeded to the next round until a winner was declared.

Coventry Bees winning at Hove Stadium, 21 March 2008 (Good Friday meeting). (© Steve Nash Photography)

CHAPTER TWO

Basic Care and Training

If you have just purchased your first greyhound, or if you have just started working with greyhounds for the first time, then the prospect of handling them can be quite daunting. Most are laid back in nature, but when put in a kennel environment the greyhound can become a pack animal, and in training it can quickly become excitable, its laid-back nature changing in an instant. Indeed in training it can be a very Jekyll and Hyde character: while generally of a genuine, loving nature, it must be understood that it is also a natural hunter.

A young pup looks upon his squabbling siblings.

BASIC HANDLING TECHNIQUES

Because of the greyhound’s nature, it is important that the novice handler gets the basic handling techniques right – even collaring up a dog or feeding it can risk injury to both dog and handler if it is not done correctly. Loose dogs can cause fights, they can run into objects or people, or a nervous dog may break free and you may not be able to catch it. Here I will discuss some of the basic but important facts and techniques that a handler should observe.

Basic Control

Putting a collar and lead on a dog may seem an easy task, but it still needs to be done correctly. The best type of collar is a wide ‘fish’ collar, as a dog finds it much harder to pull its head through these; when a greyhound gets excited it has a tendency to turn and pull its head through the collar and slip the lead. The collar should be put on round the top of the neck just behind the ears and fastened tightly, but with enough slack to get your index and middle finger underneath it. It helps if the lead has a swivel on it to prevent it getting twisted and tangled.

A fish collar; notice its thickness, which helps to reduce the chances of the dog slipping it.

A swivel lead; this helps greatly with dogs that turn around frequently while on the lead.

The following facts and techniques regarding control should also be observed:

It is important that you have full control over the dog at all times; if it gets free then it may well injure itself or other dogs in the immediate vicinity.

If a dog turns itself and tries to slip the lead, it is important not to let the lead get tight: do your best to follow the dog, all the while coaxing it to calm it down. It is when the lead is pulled tight that the dog can get some leverage and slip its head through the collar.

When walking a greyhound in public, and in particular when walking more than one, it should be muzzled. A large box muzzle should be used, and put on so that the muzzle is tight, but not so tight that the nose is pressed against the front. While I would consider this essential for any dog in training, a greyhound that is retired from racing should soon calm down, and the use of a muzzle may well not be needed. However, always proceed cautiously.

When bending over a dog to examine it or to clip its nails, it is advisable to keep it muzzled. It is also advisable to position your arm between your face and the dog’s mouth, because if you happen to cause the dog a little pain, even the most placid might turn round for a nip.

When getting a greyhound out of a kennel it should always be done with your foot or knee held firmly behind the door to stop the dog pushing past you and escaping. Greyhounds are generally kennelled in pairs, and while one dog is being collared up, the other may well be trying to escape. A loose dog is always an accident waiting to happen.

If a greyhound is running at you, or is loose and is running in your direction, then spread your arms and move backwards; and if it doesn’t begin to slow you may have to retreat a little faster. As the dog comes past you, try to grab it, but go with it as you do so: it is not wise to rugby tackle it because you could do the dog or yourself – or both – serious damage. Similarly, if you stand still and a dog runs into you, then you may be seriously injured: more than once I have seen a handler suffer a broken leg when struck by a fast-moving greyhound.

When a greyhound is loose, never chase it, because it will always run away from you, but always try and coax it back, especially if it is nervy; walking or jogging away from it will often encourage it to follow. If it is extremely nervous you may have to get another dog to try and coax it back to you; and if a familiar dog or kennel companion doesn’t work, you may have to resort to coaxing it with food.

The use of excessive force on a dog is not necessary; a naughty greyhound will not come into line by slapping it. The only time a dog should be hit is in the unlikely event of a fight, when you may need to use whatever comes to hand to break them up. If possible a bucket of cold water should be slung over the brawling dogs, though the down side of this is that it takes time to fill a bucket of water, and it might be critical to get the dogs separated without any such delay.

A box muzzle; this is used not because the greyhound is vicious in nature, but because it tends to get excited very quickly when in training.

Feeding Guidelines

When two dogs are kennelled together, you should feed them separately. If they are fed together they may well fight, nor do you know exactly how much food each dog is consuming. Place one food bowl outside the kennel and open the door to let one of the dogs out, then place the other bowl inside. Once a dog gets used to feeding outside, then it will usually come out for its food with few problems. If you have a new dog it may be advisable to put a lead on it in order to bring it out of the kennel.

When collaring up a dog to feed it outside its kennel it is advisable to place the end of the lead over its back. Some dogs are very over-protective of their food, and if you bend over the dog first to collar it up, you risk being bitten in the face. By placing the lead on its back, if it does have a little snap then you are standing up and ready to deal with the situation.

If you are working in a larger kennel environment, never feed the dogs that are outside their kennels too close together, but always leave enough space between them so they can’t get near to each other. Also, never walk a dog past another that is feeding; greyhounds can be very aggressive in proximity to their food, especially in a kennel environment.

When the dog has finished feeding, always move the bowl away from it with your foot before you bend down to pick it up.

While the greyhound is a soft, lovable, human-friendly dog, it is always best to err on the side of caution when working around any breed of dog and food. Thus, if you bend down to pick up the dog’s bowl without first moving it away with your foot, you unintentionally risk your face being bitten.

Basic Exercising and Travel Guidelines

When walking greyhounds you should never walk any more dogs than you can handle. I have seen trainers let very slightly built handlers walk sets of eight dogs. If a rabbit pops up or a loose dog runs into the set, then what chance does the handler have of staying in control? I would suggest that four dogs are enough for any one person to handle safely.

In the summer months when the days are hot, exercise your dogs in the morning and in the evening to avoid any heat-related problems. Over-exposure to the sun can be a killer, so there is no point risking their health by exercising them in the heat of the day. Black dogs always seem to suffer the worst as the colour black absorbs heat.

When travelling on a hot day, always ensure that your transport is well ventilated, and be sure to park it out of the direct sunlight. Never leave a dog in a car on a sunny day: a dog can die of heat stroke in a very short period of time.

When a greyhound has raced, it is important to let it catch its tongue before it is put on a transport or in a car; in warm weather it could be dead by the time you get back to your kennels.

Rules around the Kennels

Any dog that is ill through sickness or disease should be quarantined as best as possible. Many illnesses are highly contagious, and you should do your very best to stop any contact between your greyhounds. Many larger kennels often have their own quarantine block.

Never let young children run around in the kennel or the kennel environment; the greyhound can become excited very quickly, and accidents need to be avoided when possible.

Wheelbarrows and other such objects should be moved out of walkways and kennel areas after use. The greyhound can often be clumsy, and could do itself a lot of damage if it inadvertently walks into such objects.

Always keep your kennels clean and tidy, disinfect them at least once a day, and always try and clean up any kennel mess swiftly. Leaving faeces in a kennel not only causes bad odours, but can spread germs and disease.

A greyhound in transit. It is an advantage if the vehicle is caged out so greyhounds are kept separate while travelling; this also prevents them moving and falling about while the vehicle is in motion.

THE BASIC TRAINING OF GREYHOUNDS

There are differing definitions of a good greyhound trainer. Firstly, some people may be under the impression that because you have a very large bank balance and can afford to buy top class animals, then you must be a good trainer. However, a testament to this misconception is the number of good dogs that are put into early retirement because of the trainer’s ignorance. If you can afford to buy very expensive dogs it won’t matter how bad a trainer you are, because you will still win races, for a while.

Secondly, some people believe that trainers who can pull a large betting gamble must be very good. However, there have been some trainers, and no doubt there will be others, who have used certain pharmaceutical compounds to slow down, or speed up, their dogs. This despicable practice is, of course, illegal, and those who engage in these practices are the antithesis of what constitutes a good trainer.

In my opinion being a good greyhound trainer is about knowing your dogs and being able to give them a decent level of care. It is also important that you have a good knowledge of illness and injury so that your dogs are given proper attention and treatment. Being able to condition a dog and bring him to peak fitness at the right time is another aspect of becoming a good trainer; thus preparing a dog for a particular competition or certain race is a skill that needs to be mastered. When you can land a gamble through your own initiative and hard work, then maybe you can start to think that you can train a little bit.

If you are to become an accomplished trainer it is important that certain key areas in your training regime are set up correctly, and that all the criteria for good management are fulfilled.

Two greyhounds turned out within a large paddock.

The Kennels

A good starting point is to ensure a clean environment in which to keep your dogs. The bed should be spacious and have a plentiful supply of fresh bedding. As previously explained, any dog mess should be cleaned up promptly to combat the spread of germs and to try and keep the kennels smelling relatively pleasant. In summer the kennels should be well ventilated to prevent the occupants overheating. In winter the dogs should be kept warm with a generous supply of bedding, and you should put coats on the dogs, whether they are feeling the cold or not.

Feeding

Learning how to feed your dogs correctly is a major part of your training. Not only will you have to adjust what you feed according to whether the dog needs to pick up in condition or be let down, but you must also experiment to try and find each dog’s best racing weight. Some dogs will run well with a good healthy back, whereas others are better when they are much leaner. It is also important that your dogs are given a good supply of vitamins, minerals and other supplements, especially when they are sick or lame.

Exercise

How you exercise your dogs will also have a major effect on how they perform. Walking and galloping routines can be used to bring your dogs into condition, but great care must be taken as too much or too little work can be counter-productive. It is also important that your dogs are let out frequently so they can relieve themselves; some will contain themselves all night if they must, which is not a healthy situation for them.

Managing Injury

Having a good knowledge of the greyhound’s anatomy, and learning how to examine and treat your dog correctly, can have a considerable bearing on your success as a trainer. Failing to identify injuries, and running dogs that are lame in one form or another, can lead to frustration for the handler. Injuries are often more complicated than most trainers and even vets, would realize, and by taking the time to extend your knowledge of injuries and how to treat them will reap its own rewards.