18,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: The Crowood Press

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Serie: A Gardener's Guide to

- Sprache: Englisch

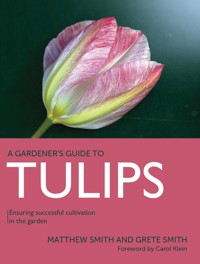

A comprehensive guide to growing tulips from bulbs, with expert advice on the most rewarding varieties. A Gardener's Guide to Tulips is a practical guide helping growers understand the tulip's lifecycle and ensure success in its cultivation. Alongside practical advice, the book also includes wider information for interested growers and admirers of tulips. With over 300 photos, a wealth of varieties and planting situations are considered, as well as case studies of gardens where tulips have been used to great effect. It will interest experienced gardeners and inspire those who may not have attempted to grow these beautiful plants before. Readers will find information on: Taxonomy and types, Cultivating and caring for tulips, Propagation and breeding, Designing with tulips in the garden, Tulip varieties, both current and past selections, Gardens and places of interest for tulips, What can be learnt from commercial growing, The fascinating history of tulips.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 261

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Ähnliche

First published in 2023 byThe Crowood Press LtdRamsbury, MarlboroughWiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book first published in 2023

© Matthew Smith and Grete Smith 2023

All rights reserved. This e-book is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication DataA catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 7198 4204 7

Cover design by Sergey Tsvetkov

Photo Credits

All photographs are taken by Grete Smith unless otherwise stated. Antsvgdal/Shutterstock.com: p. 164, bottom left; Barmalini/Shutterstock.com: p. 48; Evrenkalinbacak/Shutterstock.com: p. 133; Floralia Brussels, Castle Grand-Bigard: p. 132; John Amand, Jacques Amand Intl: p. 23, bottom, p. 145; John Wainwright: p. 150, bottom; Kelsey Gurnett/Shutterstock.com: p. 153; Dr Liang Guo: pp. 134, 135, top; Martin Duncan, Head Gardener Arundel Castle: pp. 126, 127, 128; PicoStudio/Shutterstock.com: p. 66, top right; Steve Photography/Shutterstock.com: p. 169, bottom; Stocker Plus/Shutterstock.com: p. 162; Teresa Clements: pp. 142, 150, top; Uhryn Larysa/Shutterstock.com: p. 14.

Google [Google Maps Europe/Asia]. Retrieved 10 January 2022, from https://www.google.co.uk/maps/@43.6123397,40.4405249,4.04z–p. 163;

Wikimedia Commons – Retired electrician // Map: user:STyx, CC0, Own work based on figure 1 in Christenhusz, M. et al. Tiptoe through the tulips – cultural history, molecular phylogeetics and classification of Tulipa (Liliaceae) // Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society. (2013, Vol, 172. pp.280-328)- p. 13.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank The Crowood Press for making this publication possible. There are many other people who contributed directly and indirectly with information, advice, suggestions and support, and we would particularly like to thank Teresa Clements for generously sharing her knowledge and expertise on the amateur showing of tulips in Chapter 8. Likewise, we would like to thank the Committee and members of the Wakefield and North of England Tulip Society for welcoming us to their show and introducing us to the fascinating world of the English Florists’ Tulips. We would like to thank all those who kindly supported us, shared their gardens and additional photography of gardens and spent time speaking to us about the tulips they grow: Dr Ellie McCann, Polly Nicholson, Martin Duncan, Dr Liang Guo, Nicole Pelgrims and Imogen Wyvill.

Thank you to John Amand from Jacques Amand International for the rare photos of historic tulips and of the photo Lawrence Medal Award Garden from RHS Chelsea Flower Show 1995.

We are very pleased to have included information from the adoptive country of the tulip, the Netherlands, and that would have not been possible without the help of Simon Groot. Thank you to Joris van der Velden and Adriaan Dekker for talking to us about breeding tulips and growing tulips for cut flowers.

Last but not least, we would like to thank our families and friends for patiently bearing with us when we disappeared from sight while our chapters were taking shape.

CONTENTS

Foreword by Carol Klein

Introduction

1 Tulip origins, taxonomy, types and classification

2 The bulbs and planting

3 Tulips in the garden

4 Incorporating tulips into your garden design

5 Propagation and breeding

6 Tulip varieties

7 Tulip gardens and places of interest

8 Showing tulips in the UK

9 Commercial growing

10 Tulip history

Bibliography

Abbreviations

Index

FOREWORD

Presumably if you have just bought this book or are thinking of treating yourself to it, you are already interested in tulips. You may very well grow them, perhaps you know quite a bit about them.

Lots of us gardeners grow tulips, love them and are fascinated by them. They are perhaps the most charismatic of flowers. On whatever level you appreciate them, from the elevated heights of their historical significance to the literally down-to-earth level of just planting bulbs in your garden and watching them grow, they mean a great deal to many people.

There is so much to discover about them – where do they come from? How long have gardeners been growing them? How did they come to cause the ruin of a country’s economy and centuries later become the cornerstone of that same country’s economic success?

There are chapters about how to grow this special bulb. What are the conditions that suit it? Are they best grown on their own? How do we integrate them into our gardens? On a gardening level, you will learn about the types of tulips we can grow, which to choose, and what about the species. And there are sections about how you might make your choices based on colour and flowering period. Can you grow tulips from seed? What about replanting offsets?

How do the Netherlanders grow their tulips so successfully? Their striped tulip fields are visible from space. Years ago, I made a programme entitled Plant Odysseys with Oxford Scientific Films for BBC 2. One episode was devoted to ‘The Tulip’ and in it I was lucky enough to visit the Netherlands’ bulb fields. Grete and Matthew let us into this fascinating world. They tell us not only about the techniques and practice of growing tulips but about the graft and patience, the industry and the love that goes into producing our tulip bulbs.

They talk about the Silk Road, where centuries ago merchants and travellers on horseback transported their bulbs on epic, often hazardous journeys westwards through mountainous terrain, thence to the courts of the Turks and the Ottomans and on to the flat fields of the Netherlands, to their tulip-advertising garden at Keukenhof, visited by millions, and to the Aalsmeer flower auction, the fourth largest building by area in the world, where the majority of the world’s cut flowers, especially tulips, are bought and sold.

We have insights not only into how tulips are grown commercially, but how they have been grown and developed over the centuries and how we can grow them for ourselves. Expert information about where to see tulips at their best in a variety of venues is included, not just dry data but what special features each venue boasts, illustrated with excellent photographs. When you are writing about any flower, words are brought to life by images and the photographs throughout the book are first rate. Of course the tulip has to be one of the most photogenic of flowers. The images here are mouth-watering.

The book is written by enthusiasts for enthusiasts, bursting with useful facts, informed by first-hand knowledge. You know the authors understand their subject intimately – from growing them and constantly gleaning extra knowledge from fellow enthusiasts. Within these pages you will find comprehensive and brilliantly researched answers to all you want to know about tulips, whether you are planting vast borders or a container or two. For all this information to have been brought together in one volume is a huge achievement. You need look no further except for the fact that reading these pages will inspire you to look even more deeply into this bewitching flower.

Carol Klein, Spring 2023

INTRODUCTION

This book is aimed at keen gardeners as well as budding gardeners interested in ornamental horticulture and, more specifically, in tulip growing. Practical aspects of tulip cultivation including aspects pertaining to the bulb as planting material, planting suggestions, conditions for thriving, tulip varieties and perhaps lesser-known information about cultivating tulips at a larger scale, have been included in the text. While not a central point of this book, we felt it was appropriate also to include a section on the current debate around the place of the tulip in history.

When approached to write this book, we thought of all the different ways in which through Brighter Blooms we have been involved with tulips, aside from growing them. We felt that there is often little printed information about flower shows which, after all, are a very important platform for Brighter Blooms and many other small size growers, and a great opportunity to interact with customers and people with a similar interest in plants and growing. Equally, based on Matthew’s experience of speaking to gardening groups and societies, we were aware there is a great appetite for information on public and private places open to the public that display tulips in such a way that excites and inspires visitors. Not only that, but we ourselves value the opportunity to visit, admire and understand the level of endeavour that other commercial tulip growers and amateur tulip enthusiasts invest in presenting tulips at their best to a wider public. The information provided in this book comes not only from our experience as horticulture enthusiasts and keen admirers of gardens in the UK and worldwide, but also from the experience of a small grower of tulips based in the northwest of England with over ten years’ experience of growing tulips at our nursery, and displaying at the Royal Horticultural Society (RHS) shows and other independent flower shows.

Each chapter concludes with a case study, which is a place, an aspect, or a variety that we felt we wanted to emphasise as being particularly representative for the topic further developed within the chapter.

In Chapter 1 we talk about the origins – tulips from Amsterdam? being our opening question. We then talk about taxonomy and different types of tulips, and it is this classification that we base the rest of the text on when referring to the different groups of tulips. Tulipa acuminata is the first case study, selected as such for being, in our view, a bridge between tulips past and present, an unusual reminder through its appearance of how things change, but at their core, remain appreciated.

Moving on to the practical knowledge of bulbs as planting material and factors we need to bear in mind when planting them, Chapter 2 considers the ideal conditions for bulbs to grow well and tulips to thrive in, and concludes with a very small-scale, unscientific experiment looking at the results of growing different sizes of bulbs. Chapter 3 considers the post-bulb stage of the tulips, namely, the conditions in the garden while they are growing that provide useful growing notes for gardeners. A good understanding of the full life cycle of the tulips helps growers ensure the right conditions are provided and, in return, the best displays are the result they see.

Chapter 4 offers suggestions on including tulips in garden design, alongside a discussion on colour combinations, and includes in the case study a private garden from the northwest as a great example to allow for different colour schemes and planting styles in different parts of the garden successfully.

We then move back to looking at more technical aspects related to tulips and discuss propagation and breeding in Chapter 5, which we conclude with an interview with Joris van der Velden, a Dutch tulip breeder.

Following on from breeding, Chapter 6 is where we list varieties that we have been growing for many years and we invite gardeners who may not have grown them before to consider them. All tulip varieties included in this chapter are varieties that we are happy to recommend to gardeners and tulip enthusiasts for growing.

Back on the road, Chapter 7 includes several destinations in England, Europe and further afield where tulips are expertly grown and beautifully displayed, followed by Chapter 8, where we explore the world of tulips exhibited as part of flower shows in amateur and commercial displays. The only remaining UK tulip society is the case study for Chapter 8.

We thought that writing about tulips would not be complete without referring to the very well-developed tulip cut flower industry in the Netherlands. And while a completely different approach to growing from what has been presented in previous chapters, we felt it would be interesting for readers to find out more about the scale of the tulip cut flower industry. The case study for this chapter is that of a small company based in Hem, in the Netherlands.

Finally, the concluding chapter of this book gives a synopsis of some of the older and newer publications on Tulipmania. There is also a discussion on the known accounts of the story, which has been retold many times.

CHAPTER 1

TULIP ORIGINS, TAXONOMY, TYPES AND CLASSIFICATION

Tulips have been known for over 1,000 years, and it is easy to imagine that within this time span everything that could have been learnt about tulips has been learnt; however, this could not be further from the truth. Taxonomy is the branch of science concerned with classification (Oxford English Dictionary) often through naming, sorting and categorising. The tulip has been subject to extensive taxonomical scrutiny and change, with a vast amount of effort having been put into the classification of the genus over time. As science has developed, our understanding of the tulip has changed, and this has led to taxonomical reclassification and adjustments to the genus. Even now, work continues to fully understand how the genus should be classified at a genetic level and, while most gardeners will not be concerned with the current thinking on taxonomy or historical classifications, for the readers who are, further reading can be found in the Bibliography section.

A species tulip called Tulipa cretica. Originating from the isle of Crete. One of over seventy known species of which there are many hundreds of cultivars.

There have been many thousands of hybrids registered since the seventeenth century when the Dutch started cultivating tulips. Tulip ‘Verandi’ is just one of several thousand registered with the KAVB – the Dutch Bulb Growers’ Association.

In this chapter we will consider the origins of tulip species and their geographical spread. While this may not seem to be a priority, as we will discuss here, the origin of the species lies at the basis of the conditions needed for the respective species to thrive, therefore it has a direct impact on successful cultivation, be it from the point of view of the gardener who grows tulips in their garden, or the designer who proposes where tulips should go in the garden. We will then look more closely at the humble tulip species, the starting point of the impressive tulip hybrids with which we are now familiar. Finally, and having in mind selecting the tulips, rather than focussing closely on the complicated taxonomy of genus and species, we look a little deeper into the current classification of the hybrids as these are more familiar to most gardeners and readers. Making selections based on flower shape, stem length and flowering time can be made easier when the details of tulip categories are known.

TULIPS FROM AMSTERDAM?

When the general population are asked the question, ‘Where do tulips come from?’ the answer often received from most people is ‘Holland’, or quite often more specifically, Amsterdam. And why would the answer not be that? After all, there is a song titled ‘Tulips from Amsterdam’ and the internet has thousands of photos of the Dutch tulip fields. While the answer is not exactly wrong, with approximately 70 per cent of the world’s commercial supply of tulip bulbs being grown in the Netherlands, the tulip has no native origins in Holland, or indeed, Western Europe. The fact that so many see Holland as the home of the tulip is certainly a testament to the Dutch horticultural skills that have allowed a small country to corner a huge international market, popularise the genus worldwide and become associated with the masterfully cultivated tulip.

The Netherlands is often cited as the home of the tulip, understandably so when you see the fantastic displays created at Keukenhof gardens. However, no tulip is native to the country or indeed, to Northern and Central Europe.

One of the first things to establish is the fact that there are no tulip species that are native to Central and Northern Europe. The difference between a native and a naturalised plant is that a plant that is naturalised is one that has been brought to an area with human assistance, whereas a native plant originates from that location.

The tulip originally had a quite narrow geographical spread. The most diverse cluster of native tulips is found in the Tien Shan and Pamir-Alay mountain ranges in Central Asia. Taxonomists generally believe that this is the area where the tulip first appeared. Uzbekistan alone has twenty species native to the country. The native tulip populations then form a band between western China, Mongolia and the Himalayas in the east. The Balkans are often said to form the most western extent of the native spread of the tulip, although there is one species found to be native to southern Portugal, Spain and North Africa. The band spreads no further north than southern Ukraine and central Siberia and no further south than Egypt, Iraq and Iran.

Map showing the native and naturalised distribution of tulips. The mountain ranges represent the area where the largest diversity of tulip species is found. The red lines indicate an approximate widening distribution over time.

Tulipa sylvestris is a species tulip with quite a large native spread (Central Asia – Northern Africa) that has successfully naturalised in many locations through Central and Northern Europe. It grows well in grassy meadows and deciduous woodlands.

The tulip has been naturalised in many locations around the world, and across a very long period of time, leading to a situation where establishing whether tulip species are native or naturalised can be a difficult task for researchers. Most of Europe, including as far north as Norway, Finland and Scotland has naturalised colonies of tulips with the most common species being Tulipa sylvestris. The naturalised spread of the tulip is very much linked to the historical spread of the tulip and is expanded on in Chapter 10 – History. Fifteen or so varieties have been identified growing wild in Turkey and are considered naturalised. It would appear, however, that only four of them are native to Turkey.

It is worth noting at this point and bearing in mind the growing conditions of the locations where the largest diversity of tulip species is found. Tulips are found growing in mountain ranges in some very inhospitable and remote locations, often extremely cold and wet in the winter and hot and dry in the summer. This is important, as conditions from the place of origin will influence the growing conditions needed to thrive, even when the original species have been hybridised. The tulips grown in parks and gardens nowadays bear little resemblance to the species native to the slopes of the Tien-Shan mountain range; however, they require similar growing conditions as the species to thrive.

TULIP SPECIES

Originally small, generally low growing with modest flowers, tulip species bear only a slight resemblance to the modern-day hybrids that most of us think of when we talk about tulips. Most tulip species have pointy petals which can be described as somewhat thinner in texture than the petals of the tulip hybrids. The colour ranges are more limited, with pink, yellow, lilac, purple and orange being the colours most associated with tulip species. While tulip species may not have quite the opulence, stature and presence of the hybrids, they are nevertheless highly collectable among the tulip enthusiasts community and, if the correct growing conditions are available, they will provide a display year after year, sometimes being considered more reliable as a grouping of tulips at reflowering than the tulip hybrids.

Species tulip growing in the Chimgan mountains in Uzbekistan.

The number of recorded species of tulips is subject to some debate with some papers documenting as many as 114 and others around the seventy-five mark. The problem of pinpointing an exact number is down to the variability within the species. The breeding of varieties within species and varieties documented as species that have never, as far as we know, been located within the wild has added to the confusion. A species in one part of the globe can look and grow very differently to one established elsewhere. If all species are eventually DNA sequenced, then an exact number of species will be decided upon. Until then, however, there will continue to be much debate on this subject. The seventy-five plus species documented do have quite a variation and we do not have space in this book to document every one of them. Richard Wilford’s book Tulips, Species and Hybrids for the Gardener (2006) is a great publication which describes some of the more well-known, cultivated and commercially available species and varieties.

To the general gardener much of the species debate is inconsequential, and whether or not they can be grown in the garden is the most important aspect. Some of the species do indeed require very specific growing conditions, often liking very dry or cold conditions at specific times of the year. The intolerance to wet conditions means these species tend only to be suitable for managed cultivation in glasshouse growing. Apart from those requiring specific conditions, on the whole, most species require free-draining soils; silty loam soils are perfect, heavy clay soils are not ideal. However, Tulipa turkestanica has been known to grow in a wide range of conditions and will even survive on heavier soils. Tulips are best grown in open, light sunny locations. The following three varieties lend themselves to growing in garden situations.

Tulipa turkestanica

Tulipa turkestanica grows with a few narrow grey-green leaves. Flowering In early April, flowers are creamy-white with a yellow centre and star shaped when open, growing to a height of around 25cm (10in). A single bulb will often have five or more flowers so a well-established, dense clump can be quite a sight. Tulipa turkestanica is very tolerant of a range of conditions including heavier soils so long as they do not stay waterlogged, making it one of the easiest of the species tulips to grow and multiply well over time. Its height means it sits well in the flower border without getting lost among other early spring flowers. The early flowers of Tulipa turkestanica are often covered in bees on sunny spring days.

Tulipa turkestanica is a species tulip that will tolerate slightly damper but not waterlogged soils.

Tulipa tarda

Tulipa tarda usually flowers after Tulipa turkestanica, and grows low to the ground, to approximately 15cm (6in). It produces star-shaped flowers which are intense yellow in the centre and white around the tip and the exterior top part of the petals, a colour combination which makes Tulipa tarda glisten in the early spring sunshine. The foliage is relatively insignificant with thin, linear green leaves surrounding the flowers, which emerge centrally. When planted in dense clusters, Tulipa tarda produces great splashes of early colour to gardens. Tulipa tarda was assigned the Award of Garden Merit by the RHS in 2015.

Species tulip Tulipa tarda works well planted in rockeries or right at the front of well-drained flower beds.

Tulipa humilis

Tulipa humilis is a species that has numerous varieties in cultivation which we feel gardeners should consider, due to its versatility and reliability. The original Tulipa humilis is of a lilac colour, with the interior centre of the flower yellow. Most other varieties pertaining to this species retain the yellow centre, but many are more intense in colour. Varieties such as ‘Persian Pearl’, ‘Little Beauty’ and ‘Little Princess’ perform very well in gardens, in sunny, well-drained locations where they multiply freely.

Tulipa humilis has many cultivars that grow very well in sunny, free-draining garden areas. The true species is rarely grown, as its cultivars have a broader appeal.

HYBRID TULIPS – CURRENT TYPES AND CLASSIFICATION SYSTEM

Tulips have been grown, bred, described and classified for hundreds of years, and many books have been published detailing links between historical developments and classifications. For all plant species that have been subjected to extensive breeding over a long period of time, classification systems have been adapted and altered over the years. Tulips are no different. The current classification arose out of a need to organise the vast number of new varieties that had been bred at the end of the nineteenth century. Nomenclature at the time was also very confused, with many of the new varieties being given names that were already in use for a different variety. In 1913 the Royal Horticultural Society (RHS) decided to address this issue by creating a Tulip Nomenclature Committee with the task to establish a classification scheme and resolve the overlap in names. Tulip trials were established at Wisley Gardens during 1914 and 1915 and a final report was published in 1917.

The following fifty years saw a tremendous amount of work into further classifying and renaming tulip varieties. Many subgroups or divisions were discussed at that time, including Broken Breeder Tulips, Mendel Tulips and Cottage Tulips, the latter being a subdivision dropped a long time ago, but which is still mentioned occasionally today. By the 1960s there were twenty-three different subdivisions listed in the tulip classification system, and in 1967 it was decided that a complete overhaul of the system was needed again. Consequently, the subdivisions were changed leading to a reduction of just fifteen subdivisions. Between the first RHS publication – ‘A Tentative list of Tulip Names’ in 1929 and the last paper publication by the Dutch Royal General Bulb Growers Association – ‘Classified List and International Register of Tulip Names’ in 1996, which had a supplement published in 2005, there have been fourteen editions of an official tulip list. These have been produced to assist both the horticultural industry and keen gardeners with correct names and specific information for each variety, such as flowering class or type, colour and height.

The 1996 ‘Classified List and International Register of Tulip Names’ was the last official paper publication, although in 2005 the long-awaited supplement was published (in Dutch mainly) that contained approximately 1,500 new tulip cultivars, updates and corrections that had occurred since 1996. The 1996 edition contains over 5,600 tulip names, of which 2,600 were in cultivation at the time and in most cases readily available to the trade and consumer, according to the preface. The 1996 edition includes all the cultivars in the 1987 edition plus all the new cultivars since 1987. The edition also tries to correct some of the duplicated naming that was created by the practice of reusing names after a few years of cultivars not being seen in commercial production – a practice now frowned upon. This, we assume, has led to some of the inventive names we see nowadays –Tulip Hotpants, for example. Naming of tulips has always been down to the breeder of the variety, with some named varieties gaining popularity through associations. Tulip Rococo, for instance, is aptly named after the elaborate art style.

A good use of creative, if not descriptive naming, Tulip ‘Hotpants’ and Tulip ‘Healthcare’.

Varieties with people’s names often have significance with individuals, making them popular choices, Tulip ‘Shirley’ being a case in point.

Since the last paper supplement in 2005, the Dutch Royal General Bulb Growers Association has overhauled its website to allow for new tulip varieties to be registered, catalogued and updated online. This change is a much welcome one, as the list is now always up to date and can be searched electronically. Today we have a tulip classification list that contains fourteen subdivisions, or fifteen if the Miscellaneous group is included. The Miscellaneous section is not a cultivar group, but is used to cover the entirety of the wild species and their cultivars that do not have a place in the fourteen groups. As breeding continues, new and interesting varieties emerge that blur the boundaries of the groups. For example, which group should Tulip Exotic Emperor feature in? It is both a double and a Fosteriana tulip. The same could be said for Tulip Green Mile, which is registered a lily-flowered tulip, but displays very prominent green marking as categorised in the Viridiflora group and also has fringed edges. There is further an argument that the current list is ready to be augmented with an additional tulip group – the Coronet (or Crown) group. Unlike other groups, tulips from the Coronet group have a very distinctive appearance, with the tips of the petals giving the impression of having been pinched, thus creating a crown-shaped flower. Tulips from the Coronet group are also described as having a much firmer texture than other varieties.

Tulip ‘Green Mile’ crosses three group boundaries: officially registered as a lily-flowered tulip, it could quite easily be classed as a Viridiflora or a fringed tulip.

A new group of tulips yet to be classified by the Dutch Bulb Growers’ Association, Coronet tulips have distinctly pinched petals, making them look like a crown. Top to bottom: Tulip ‘Red Dress’, Tulip ‘Striped Crown’ and Tulip ‘Elegant Crown’.

We have included this classification for tulips in our book, as we think it is important to be aware of particularities of tulips that belong to the same grouping, this classification providing gardeners with an easy way to distinguish between tulips in terms of flowering time, petal or flower shape or flower opening habit. The groupings that different varieties fall under are included in information available when purchasing the bulbs and are a very helpful shorthand for busy gardeners. The classification of cultivars in Tulipa (1996 ‘Classified List and international Register of Tulip Names’, Royal General Bulb Growers’ Association KAVB) is detailed next, together with examples of varieties in each grouping and further explanation where necessary. Most of the varieties we have included here are commercially available and we have grown them on our nursery for many years. Further examples are provided in Chapter 6, with additional information for each variety.

Single Early Group

Single-flowered cultivars, mainly short stemmed and early flowering.

Examples of Single Early Group varieties. Left to right: Tulip ‘Flair’, Tulip ‘Christmas Dream’ and Tulip ‘Purple Prince’.

The early nature of this group means that some of these varieties can be the longest lasting; they flower when the sun is still weak and the days are a little shorter. The shorter stems also make them a great addition to the flower border, especially on windier sites. Often used in the forcing trade for very early cut flower tulips.

Varieties: Tulip Flair; Tulip Christmas Dream; Tulip Purple Prince.

Double Early Group

Double-flowered cultivars, mainly short stemmed and early flowering.

Examples of Double Early Group varieties. Left to right: Tulip ‘Abba’, Tulip ‘Monsella’ and Tulip ‘Foxtrot’.

Fully doubled flowers that tend to last a long time without getting top heavy like some of the longer stemmed later varieties. A good range of colours is now available.

Varieties: Tulip Abba; Tulip Monsella; Tulip Foxtrot.

Triumph Group

Single-flowered cultivars, stem of medium length, mid-season flowering. Originally the result of hybridisation between cultivars of the Single Early Group and the Single Late Group.

Examples of Triumph Group varieties. Left to right: Tulip ‘Jimmy’, Tulip ‘Abu Hassan’ and Tulip ‘Don Quichotte’.

This group contains by far the largest number of varieties. A lot of varieties being bred currently are for the cut flower industry and this group is favoured amongst the cut flower growers. The medium stem length makes them a popular choice in the garden.

Varieties: Tulip Jimmy; Tulip Abu Hassan; Tulip Don Quichotte.

Darwin Hybrid Group