9,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Terra Nuova Edizioni

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

After university Jenny Bawtree went to teach English for a year in Florence and lost her return ticket. She continued teaching there for five years, ending up as a reader in the University of Florence, but then decided to change career and set up a riding centre in the Tuscan countryside with, in her own words, “no money, no experience and certainly no business sense”. One thing she had plenty of was luck, and she managed to create one of the best-known and best-loved trekking centres in the country. This is the story of her Tuscan adventure. A protagonist of the book is the ramshackle farmhouse she fell in love with and restored over the years: it is no longer ramshackle, but still an easy-going place where guests feel immediately at home. During the story we meet her parents, who came out to Italy to live near her, and her son Nicholas, who at the age of eight decided to become a journalist (he succeeded). We also meet Pietro, a peasant farmer who right from the beginning helped her to create the riding centre and became a lifelong friend; Sergio, his son, whose ability to build walls, lay down a terracotta floor, grow vegetables, shoe a horse, you name it, is legendary; Mario, who laced his riding lessons with choice swearwords; a hundred-year-old horseman; the lady with the di-ag-on-al pee; a lascivious maresciallo; a portly lady with an ‘aubergine’; and many others. This is the light-hearted story of a courageous woman and her love affair not only with horses, but also with the Tuscan countryside, Tuscan art and architecture and the Tuscan way of life.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Ähnliche

© 2015 Jenny Bawtree

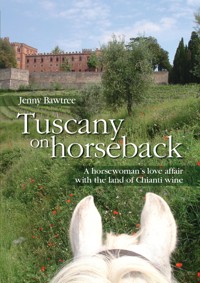

Cover design: Andrea CalvettiFront cover: Castle of Brolio (Gaiole in Chianti), photo taken by Jenny Bawtree riding Silver.Back cover: Jenny Bawtree riding Sheba with her dog Michie at Casa del Bosco (Mercatale Valdarno) in the sixties, photo by Raymond F. BawtreeLayout: Nicholas BawtreeIII edition May 2023

Published by Editrice Aam Terra Nuova, Via del Ponte di Mezzo 1, 50127 Firenze - [email protected] - www.terranuovalibri.it

ISBN: 9788866818915

Versione digitale realizzata da Streetlib srl

NOTA DELL’EDITORE

Caro lettore, cara lettrice, grazie per aver scelto Terra Nuova Edizioni. Fin dal 1977 siamo impegnati a diffondere le idee e le pratiche dell’ecologia, della sostenibilità ambientale e dell’economia solidale attraverso la rivista mensile Terra Nuova, i libri (cartacei e digitali) e il sito www.terranuova.it.

In ogni nostra pubblicazione troverai contenuti aggiornati, passione, senso di responsabilità nel fare impresa. Questo per noi significa in primo luogo avere rispetto per chi lavora, garantendo ai nostri collaboratori (autori, traduttori, redattori, editor, grafici, tipografi, distributori ecc.) il giusto riconoscimento economico per l’impegno profuso.

Ti chiediamo di condividere questo sforzo scegliendo di non duplicare questo ebook: se vuoi farlo conoscere o regalarlo, compralo nuovamente. La duplicazione illecita è un gesto che sembra innocuo a chi lo compie, ma i mancati introiti danneggiano le nostre attività e i nostri progetti, e chi lavora per realizzarli. Terra Nuova Edizioni non riceve finanziamenti pubblici e i tuoi acquisti ci consentono di mantenere relazioni di lavoro corrette e di continuare a difendere l’ambiente e tutelare la... bibliodiversità!

Per saperne di più: www.nonunlibroqualunque.it

I dedicate this book to Pietro, sadly no longer with us, who in turn dedicated many years of his life to the creation of Rendola Riding.I would also like to thank Sergio, Pietro's son, Marco, Pietro's grandson and the whole Pinti family which has stood loyally by my side for so long.Nor must I forget all those who have worked unstintedly for Rendola over the long years since its foundation way back in 1969.Lastly I would like to thank my son Nicholas who, in spite of all the constant demands on his time, has spent many hours helping me to produce this book.

Contents

Introduction

Chapter 1

Unpromising beginnings

Chapter 2

Riding in Tuscany

Chapter 3

Riding in the Abruzzi mountains

Chapter 4

A new way of life

Chapter 5

Moving to the mountains

Chapter 6

Centro di Equitazione Vallombrosa

Chapter 7

The secret treasures of the Casentino valley

PHOTOS

Chapter 8

Jenny buys Casa Padellino

Chapter 9

Ups and downs at Rendola Riding

Chapter 10

Riding in the Chianti region

Chapter 11

The years roll by

Chapter 12

Pietro and his book

Envoi

Plus ça change...

Introduction

As I lay in my sleeping-bag still half asleep I heard a continuous sighing noise and my heart sank. Another day of rain. We were towards the end of our autumn tour of the Chianti region on horseback and the previous day we had ridden through intermittent showers. None of our raincoats had seemed to be completely waterproof: water seeped in behind our necks, up our sleeves and into our boots. Once you get wet you get cold and at a certain point I had asked the riders to get off and walk, the best way to get the blood circulating again. Most of them were glad to comply, but the girl from New York complained that her boots were too tight and she was better off in the saddle, so I allowed her to stay there. Of course, when we got back on to the horses the saddles were wet and we could feel the damp spreading to our underpants. Luckily the last part of the ride the sun came out just as we came to the top of the Chianti mountains, and we trotted along the lane with the sheep-pastures on either side brilliant with raindrops, gazing down at the ragged clouds in the valley below us. With a flurry of bells the sheep raised their heads to watch us pass.

We turned westwards and started to descend through woods of ilex and chestnut until we reached a natural platform above the ancient farmhouse of Scandelaia, where we paused to allow our horses to graze. From this point we could see the whole of Chianti, hill folding into hill, spread out before us: dark lines of cypresses stood out against the luminous yellow-green of the vineyards and the sombre hues of the woodland. It was the riders’ first glimpse of Chianti and they were enthralled.

The sun stayed with us although there was a keen wind and we descended in good spirits towards Corbina, the abandoned farmhouse where we were to stable the horses. Even the girl from New York did not complain when I asked everybody to get off and lead their horses because the track was particularly steep and stony. Up on the hilltop were Etruscan tombs, I explained, and there were others at the base of the hill, so this trail was probably made by the Etruscans more than two thousand years ago. Somehow this notion made the walking less arduous. After we had remounted there was less than an hour to go, and by the time we reached Corbina our clothes were almost dry.

As usual Pietro had prepared the picnic table in the barn, and when we had put the horses away and untacked them we were glad to satisfy our appetites, grown keen after nearly four hours of riding. There was hot soup, followed by mozzarella, tomatoes and Parma ham, accompanied by Chianti wine from a straw-covered flask, then a fruit tart and coffee. Their good humour restored, the riders got into the van and Pietro drove them off to Siena, all seven of them: two couples from California, the girl from New York and two robust and loquacious middle-aged ladies from the West Country. There were only two men in the group, but that was normal, in fact often there were only women. One of the men, an elderly lawyer, eased himself very carefully into the van, and I suspected that his back was aching again. But no doubt he had some pills with him to alleviate the pain: I have never known Americans to come without medication for every circumstance.

My riders had spent a day in Siena yesterday and the weather had spared them, though the wind was still keen. But today was going to be the last day of their ride, and I didn’t want them to get wet again. It was important that the last day should be fine, because it would be their last impression of the journey. Somehow it mattered less if it rained earlier on during the ride, as what they would remember best would be this last day. And it was raining! But was it? I opened my eyes, and saw that it was not raining at all; the sighing noise I had heard had been the breeze in the branches of the poplar tree just outside. I sat up on the bed and looked out of the barn. On the ridge the church of Nebbiano was etched against the lightening sky, laced with fine cloud. Mist lay in the steep valley in between, so that the umbrella pines seemed to be suspended in the air. Mist usually preceded a sunny day. With relief I pulled on my clothes, still damp after the night. In spite of the damp I love sleeping in the open-sided barn, as it is airy and, above all, silent: I find that I cannot sleep well in the stable because horses make a lot of noise during the night. They lie down with a thump, they get up with a scrabbling of hooves, they munch, urinate, defecate and sometimes squabble, uttering squeals of annoyance. I am a light sleeper and the least noise awakes me. My colleague Pietro can sleep through it all and likes to pass the night in the little room next to the stables. In the old days, probably more than fifty years ago, the stables were full of oxen. The little room, with a sink and a small fireplace, was probably used by the peasant when he was waiting for an ox to calve. Pietro props his bedsprings and mattress on bales of straw because he finds it easier to get up in the morning when the bed is high off the ground.

So I dressed, pulling on my dirty riding trousers. I would work in these, and then put on some clean ones when my clients arrived. As I sat on the bed I could smell coffee brewing, one of the most wonderful aromas in the world. It meant that Pietro had already got up, given a biscuit of hay to the horses, and then put the coffee on the gas stove. He is well over seventy years old, but an earlier riser than I am. Feeling a little guilty, I hastily finished dressing and went out of the barn to the former pigsty that we used as our kitchen: Pietro kept the crates of food in the empty troughs.

“How were the horses last night?” I asked as I sipped my coffee. “Vulcano got free,” Pietro replied, “he undid his knot again, so I tied him up with ten knots, and this morning he had undone only three.” I nodded. Vulcano is a sort of equine Houdini and would work all night with his teeth at the knots in the rope that tied him to the manger. Evidently he regarded them as a challenge. “And what about Rufus?” “This morning he started pawing, bang, bang, bang, always three bangs at a time. But he stopped when I gave him his hay.” I nodded again. Rufus is an Anglo-Arab and patience isn’t one of his virtues, particularly where food is concerned. Put something to eat in front of him and he quietens down immediately. There are people like that.

I drew on my stable boots and went into the stable. The horses, each tied to the mangers in front of them, turned their heads to look at me and then continued eating. These were stables designed for oxen, with a long, low manger running from wall to wall. A ring was attached at intervals to the front of the manger and it was to these that we had tied the horses. We had made partitions between them by suspending wooden poles from the rafters with bale string. The separate stalls created in this way looked precarious but the horses were used to them and would all lie down for an hour or two peacefully during the night. Many people believe that horses will not lie down unless they have spacious boxes to themselves, but this is not true: they are adaptable animals and will lie down anywhere for a few hours as long as they feel relaxed. To prove it you just had to look at Silver and Arabis, the two greys, whose sides were amply smeared with fresh manure. I sighed. They would have to be washed before the clients arrived.

Pietro and I watered the horses, filling the buckets from a circular plastic tub outside the door. Sergio, Pietro’s son, had filled it up when he had come with our lorry full of hay and straw. Yesterday morning a baby edible dormouse had fallen from the rafters into this tub, but luckily we were able to remove it before it drowned. The horses drank at least a bucket of water apiece. This farmhouse, which once housed a dozen oxen and at least as many sheep, now had no water supply, and the fields around it which once supplied the livestock with hay and straw were lying fallow, so we had to bring everything the horses needed in our elderly lorry.

We started to clean the horses, using currycombs and dandy-brushes, with the body brush to give them an extra shine. Their feet I had cleaned, checked and greased the day before, to make sure that no horse was missing a nail, as on this rocky terrain a lost shoe can ruin a hoof. At a certain point I left the grooming to Pietro and started to saddle up, securing the girths very gently at first, as some horses object if you pull them up too tightly right from the beginning. Some try to nip you, some raise a back leg, most just give you a dirty look. I saddled all eight horses and washed the two greys with a bucket of cold water and a sponge. Later I would return to pull the girth up another hole, once the horse had got used to the pressure. Then I would put on the brushing-boots on some of the horses to prevent them from injuring themselves with their own ironclad feet. It takes as long to saddle a horse as to clean it because everything has to be done with great care: saddle a horse badly and a saddle sore can be the result.

Now the horses were all saddled and they were looking round at me expectantly: they knew it was time for their pellets. I removed a sack of feed from Pietro’s little ‘bedroom’ and began to distribute it with a measuring tin, throwing it into the mangers in front of each horse. The bigger ones received up to six pounds of feed, the smaller ones not more than four. As they waited their turn they whickered and pawed the stable floor. Once they were all munching happily we left them to it, as this was the moment that I felt they should be left in peace. Returning to the pigsty we had our breakfast too: some biscuits dipped in camomile tea for Pietro and a plate of muesli and milk for me. Experience has taught me to drink only milk for breakfast, because it passes more slowly through your body than other beverages, and so you do not need to stop during the ride to ’go to the restroom’, as my clients quaintly describe the process of squatting in the bushes in order to pee.

Pietro now drove away in the van in the direction of Siena, in order to fetch our riders for the last lap of the journey back to Rendola, our home. I tidied up my things, putting them away into my rucksack, and then sat on the wall outside my barn looking up the valley. The mist had dispersed, and the sky had become completely free of clouds. Thank goodness, it was going to be a wonderful day. We would ride in the direction of the Castle of Brolio, resplendently pink behind its grim grey walls, then descend into a wooded valley loud with streams until we reached the Brolio mill, now a farm holiday centre. We would then canter up through vineyards to the medieval village of Rietine, before descending towards the castle of Meleto, fortified with round towers. If we had time after a picnic we would take our riders to see the inside of the castle, decorated according to eighteenth-century taste and containing a tiny theatre not touched since its inception. After that we would climb the wooded hills up to the top of the Chianti range and down towards home, Rendola.

As I waited, enjoying this lull, I thought for the umpteenth time how lucky I was. People travel hundreds, even thousands of miles to take part in this trip, paying to do so, while I can do it several times a year, for free. It is true that it is quite a responsibility to guide a group of riders of mixed ability round the Chianti area. I can trust my horses to behave well ninety per cent of the time, but there are always unforeseen events that even quiet horses might react to with a shy or a buck. It could be a pheasant that flies out from under the horse’s feet, a motorbike suddenly roaring round the corner, even a harmless seeker of mushrooms who unexpectedly stands up in the undergrowth to watch us pass. It is then that you see the quality of the rider, as well as his experience. If something unexpected happens, and sooner or later it always will, the good rider grips his knees, shortens his reins, reassures his horse with his voice. The less experienced rider’s first reaction is to adopt what I call the fetal position: he crouches over the reins, making it all the easier for the horse to take off. Some (usually women, I’m afraid) resort to panic, abandoning the reins altogether and clasping their arms round the horse’s neck. If the horse has bounded forward, as soon as he stops the rider will fall off by the sheer force of momentum.

But most of those who take part in this tour of Chianti are reasonably good riders, so I can usually relax and enjoy myself. With eight people of like minds thrown together in close proximity for the space of a week, within a day or two you reach an intimacy which is surprising. I have made some of my best friends during these rides. So, though I have done this journey dozens of times I never get bored. The company is always different and nature itself changes from ride to ride, so none is exactly like another. I have been touring Tuscany on horseback for more than forty years now, and yet I enjoy the ride every time I do it.

Forty years! It only seems yesterday that I set up my riding-centre, full of enthusiasm but with little money and even less experience. I knew how to ride, more or less, and that was all. And yet now I was running one of the best known centres in Italy. How had it happened? Well, I admit I have worked hard. But perhaps luck had a hand in it: I happened to start just at the right moment, when riding was beginning to be no longer the prerogative of the rich, the noble and the military. And right from the beginning I had had people round me who shared my dream and helped me to realize it.

It was then, as I sat on the wall beside the barn at Corbina, waiting for my group of riders to arrive from Siena, that I decided to write the story of my riding-centre. It could certainly interest the hundreds of people who have over the years come to ride with us. It could interest anyone who loves riding and Italy, where this story is set. It might, who knows, even interest people who have never ridden at all but who are curious about this activity which seems to fascinate such a large number of people. Who knows, they might inspired to take up riding themselves. If so, I will really feel I have achieved something by writing this book.

CHAPTER 1

Unpromising beginnings

If you had told me when I was a child that one day I would be running a riding-stable in Italy I would never have believed you. My plan was to be a writer. My best friend Diana and I had decided upon our future at the age of ten. We were going to travel round the world with a horse-drawn caravan, writing books as we went in order to earn our living. Children’s books, of course, the only ones in our opinion worth reading. I had already written one, a tear-jerking story of a little boy and a horse, heavily influenced, I see now, by Mary O’Hara’s ‘My Friend Flicka’. Another one, ‘The Valley inside the Mountain’, a story featuring dragons both virtuous and evil, ran to hundreds of pages before I tired of it. These manuscripts remain in my bottom drawer: the first appears to be written and illustrated by Countess Atlanta, the second by Antonia Ekberg. I obviously found my own name unglamorous. Diana and I also produced a magazine called ‘Peanut Papers’. Together with two friends, Astrid and Shirley, we wrote short stories, poems and drew lengthy cartoon strips. Only Astrid was any good at drawing. I remember a cartoon strip of mine featuring the adventures of a red rubber ball, which even I could manage to draw. Any gaps we filled up with jokes pilfered from the Reader’s Digest. Somehow that was permissible: Shirley purloined other material, passing it off as her own, and was banished from the administration. Of course there was only one copy of the magazine, so we would pass it round the class charging one penny for the privilege of reading it.

Then there was my historical period. My parents ran a hotel in the countryside near Oxford and a lady historian would come and stay in the summer bringing her bookish daughter Mary. We would sit on a little lead roof reached by climbing out of an attic window, therefore not attainable by adults, and scribble away incessantly. Our favourite theme was the return to the past of our hero or heroine – usually a heroine – by some magic means. It was hardly original but offered endless permutations. The past in my case was always the Middle Ages (still my favourite period in history, though I am now more interested in its art and architecture) and the story would be set in a castle, with all the secret passages, ghosts and skulduggery I associated with those times. I don’t think we paid much attention to style or quality: the important thing for each of us was to write more words than the other. As we finished each page we would count the words on it, and after a morning’s work we would tot up the total. Whoever had written more words won the contest. I remember too that we felt we should get as many words as possible on to a single page, and so our writing grew smaller and smaller. I don’t think we were in the least interested in each other’s efforts, so obsessed were we with pure numbers.

I used to write poetry too, but I did that alone, Poetry does not lend itself to group efforts. I remember a poem about a horse standing in the shade of a tree on a summer’s day. Another about a dream started:

“I galloped by the silver sea upon the silver sand.”

In the dream I was lifted with my steed into the heavens and there experienced all sorts of ecstatic feelings until I woke up sadly in my bed. I had been on holiday in the Tyrol and I think the ecstasy in my dream stemmed from the excitement I felt when we climbed to the top of a snowy peak near Innsbruck. But I found poetry hard work because in those days a rhyme scheme was obligatory, and I certainly couldn’t fill up the pages with the speed with which I wrote prose.

As you can see, horses often appeared in my scribblings. It was, and probably still is, quite usual for little girls to be horse-mad in England, particularly those who lived in the country. Ever since I was five I used to draw horses, all with blobby eyes and rigorously looking towards the left. I saw one of these drawings years later, and it struck me that like most children who draw horses, I made no effort to show the difference in shape between the back legs and the front ones: each leg was an elongated rectangle, with no bend at knee or hock even when the horse was supposed to be galloping, and with a black square attached to the end of it representing the hoof. The tail would spring exuberantly from the horse’s rump with no indication of a dock, the bone inside the top part of the tail. I probably didn’t know it existed.

We were not really a ‘horsy’ family. When my parents ran a pig-farm in Devon at the beginning of the Second World War they occasionally bought a horse, but it was usually when they went to a local fair and felt sorry for some elderly nag which would otherwise have ended up in the knacker’s yard. I remember hearing about one called Elsie which my father bought for five pounds. She took about an hour to cover the mile home and eventually collapsed into a ditch.

When the war broke out my parents had difficulty in finding foodstuff for the pigs and eventually had to sell them, no doubt for meat, though some of the sows were of valuable stock. They then tried rearing rabbits, but these all died of some mysterious disease, as rabbits tend to do. For a period they grew flowers – Devon has a mild climate – but they didn’t manage to make ends meet that way either. Perhaps one associates flowers with the happiness of peacetime, not war. Then my father set up a firm that contracted out farm machinery. He was also part of the local Home Guard. At the beginning of the war it was considered quite likely that Hitler would invade our shores and the people living near the coast had to be prepared, with pitchforks if necessary. (Most of the men were farmworkers.)

Children’s drawings of horses

Over the years I have seen a lot of children’s drawings of horses and it has been interesting to compare them. One particular I have noticed: in almost every case right-handed children’s horses face to the left, while left-handed children’s horses face to the right. I expect the same rule applies when they draw human faces. Withers are usually lacking and manes either stick up in a bristly manner or flow in the wind - even if the horse is standing still in a stable. One little boy drew a picture of a horse with such a big belly that he felt impelled to write underneath: “E’ incinto.” (It’s pregnant). However, the adjective, ending with an ’o’ and not an ’a’, denoted that the horse was male. My son Nicholas’s horses had a very curious anatomical characteristic: from behind the ears neck and body would slope down at forty-five degrees, making it well-nigh impossible for a rider not to slide down towards the tail and thence to the ground. As for the tack, bits rarely seem to enter horses’ mouths and saddles are usually drawn without a girth.

But even great artists can get it wrong. The eighteenth-century painter George Stubbs actually dissected equine cadavers in order to study their skeletons and musculature and his drawings of horses are anatomically accurate as well as beautiful, so much so that they still appear in the textbooks of veterinary courses. It was only when he painted one of his rare pictures of horses galloping that his study of dead horses failed him: the horse’s front legs were exactly parallel to each other as were their back legs, similar to their positions on a rocking horse. It was not till the gaits of a horse were filmed and then seen in slow motion that it became apparent that neither pairs of legs are lined up side by side when a horse is galloping.

It was during these war years that I was born, in 1942. Actually I was born in the nearest city, Plymouth, during an air-raid, my mother said. She was often given to exaggeration, but this time what she said was probably true because Plymouth was a port and was regularly bombed by the Germans. I was a very small baby because I was born after my mother’s pregnancy of eight months. My mother said that I fitted into a shoe-box. One of the neighbours had a look at me and said to my mother: “You’ll never rear ‘er!” My brother’s comment was that I looked like a monkey. I was certainly no beauty as I had hepatitis and was an unsightly shade of yellow. However, I survived.

I remember little about my early childhood, but I do remember the end of the war. To celebrate bonfires were built the length and breadth of England and one was built on a hill near our farm on the edge of Dartmoor. My sister told me that she was one of the two little girls that set it alight. The hill was called Bren Tor and it had a church on top of it, so it was a well-known landmark. I have only a vague memory of the bonfire but I remember all the people collecting there and the joyful excitement in the air.

In the end my parents left the farm and moved to Oxfordshire to start a hotel. They rented a large Elizabethan manor house about seven miles from Oxford. It was called Studley Priory because it was built on the site of a Benedictine convent. Some of the walls of the manor house had belonged to the priory and were ten feet thick. There was an arch in the garden which dated back to the twelfth century and we were told that the walled vegetable garden, which was about two acres, was of medieval origin. Once I was playing at the far end of this garden and I found a plant called birthwort. I was very excited because it had an asterisk in my flower-book, which meant that it was very rare indeed. The book said that the plant was used in the old days to induce miscarriages. One wonders what those nuns had been up to.

Starting a hotel from scratch entailed a lot of hard work for my parents and Wilma, a friend they had made in Devon and who had agreed to collaborate. None of the three had any experience in hotel management but what was worse, they had very little capital. To furnish the house, which was very big – it had more than twenty bedrooms to start with – they had to buy stuff at local auctions. They never managed to furnish the place as well as it deserved, and in consequence had to keep the prices low. I remember that some of the clients looked a bit sniffy when they arrived and saw the rather shabby appearance of the furniture. But they became reconciled to the place as soon as they discovered what a wonderful cook my mother was. My father entertained them in the oak-panelled bar – he was barman as well as manager and porter – and many of our clients became good friends. I think my father was happy with the job, it was only the weekly meeting with his bank manager that he dreaded. My mother on the other hand was tied to the kitchen and felt that she could not dedicate enough time to her three children, my sister, my brother and myself. It was, however, a wonderful place to grow up.

My sister went through a brief horsy stage in her early teens and we still have a photograph of her riding Jaunty, a cobby animal with shaggy hair. The occasion of the photo was a meet that was held on the grounds of our hotel and she admits herself that she took part only in the beginning of the hunt. Her riding phase did not last long. I think she was at the age that she soon became more interested in boys than horses.

I had my first riding-lesson when I was seven. There was a farm about a mile from the hotel run by the Honor family and they had a pony which they allowed us to use. Like most ponies he was very naughty and apparently couldn’t be trusted to carry me round on his back without being held: we were told that he would jump out of the field and gallop along the lane, with or without his rider, who in my case would probably have fallen off anyway. So Wilma, my parents’ colleague, used to run up and down the field holding the pony and teaching me how to trot and canter. I took it for granted then, but realize now what a noble undertaking that was.

Although I had a brother (Michael) and sister (Josephine), they were respectively five and eight years older than I was and I didn’t see much of them during my childhood. They both went to boarding-school and during the holidays they often went to stay with friends. When they came home they tended to stay together, ignoring my presence altogether. This I didn’t mind, as when they did take notice of me it was generally to tease me. Though I do have to give my sister credit for teaching me to recognize classical paintings from a catalogue published by ‘Medici Prints’, and also drilling me in the capitals of the world. “Morocco!” she would fire at me, fixing me with a schoolmistressy glare. “Rabat.” “Greenland!” “Reykjavik.” (Luckily I wasn’t required to spell the word.) However, in spite of these educational moments it was only when we became adults that we became friends at last.

I grew up into a quirky, fiercely independent, rather cantankerous twelve-year-old. In fact, I decided that twelve was the very best age to be and would have preferred to remain at that age. Nowadays, of course, twelve-year-olds are already experimenting with make-up and showing an interest in clothes, even having their first boyfriends, but in those days twelve-year-olds were still children and were in no particular hurry to grow up. I was quite a tomboy and loved wandering around the woods alone. Already from the age of seven I was interested in wild flowers after receiving a little book called ‘Wild Flowers at a Glance’. (I still have it.) Even now I remember the charming names of those wild flowers: jack-by-the-hedge, lady’s slipper, yellow archangel, creeping jenny… I got into the habit of pressing flowers, sticking them into an exercise book with little strips of sellotape and writing a description of them, no doubt ignorant of the proper botanical terms. I was later accompanied on my walks by my cocker spaniel Sooty. We had bought him as a puppy from Honor’s farm, and I remember carrying him home cradled in my arms. Three hundred acres of woodland came with the hotel and Sooty and I used to explore it together, crossing the walled vegetable garden and walking down the yew drive to reach it. There was one yew tree which I always stopped to look at: two of its branches about five feet from the ground had grown towards each other, fused, and then continued in their original directions. (Fifty years later I revisited the wood and found the tree again.) Beyond the wood was a copse which glowed with bluebells in the spring and then you entered into the wood proper, full of mature oak trees. There were endless tracks to explore. One led to the grave of some of the previous owners of the house: it was surrounded by a high iron fence and was decidedly spooky. Then there was Clay Drive, which ran down to the bottom of the wood and tried to suck your boots off if it could. Down there was Mokoe, the ruins of an abandoned farm, another forbidding place. But Sooty and I went everywhere. Sometimes I was accompanied by Wilma’s dalmatians, Julie and Gary. On one occasion they happened on a fox’s earth, pulled out the cubs and began to maul them. I tried to save the poor creatures, which had not yet even opened their eyes, but they were all injured except one. I had to finish them off smashing the heads against a tree, turning my head away as I did so. I carried the survivor home and my father tried to rear it, but it only lasted a few days.

Nowadays no parent would allow a child to wander about alone so far from home. But there were fewer dangers then. I suppose paedophiles existed, but we were not aware of them. It is true that at school we used to repeat a choice bit of conversation:

“To the woods! To the woods!”

“No, my mother wouldn’t like it!”

“Your mother’s not going to get it!” These words were spoken in a definitely lecherous voice which left no doubt that we knew what “it” was.

“I’ll tell the vicar!”

“I AM the vicar!”

We would rehearse this interchange with relish, but still felt no fear about wandering about the woods unaccompanied. It is sad that children can no longer enjoy this freedom.

It was about this time that I went for a week’s riding-holiday in the New Forest and I began to have proper riding-lessons at last. For a treat we were taken out into the forest to ride. I made friends with a boy called Duncan and I remember that once we galloped off together away from the other riders, urging our ponies over grass and bracken. When the guide scolded us, we said that our mounts had run away with us and that we hadn’t been able to stop them. I don’t remember if she believed us. I remember too that every afternoon Duncan and I would have to clean tack, which seemed the most boring occupation in the world. I still find it boring.

There was a riding-stable on Port Meadow just outside Oxford, and once my brother and I went riding there. I was given a chestnut pony called Flash. The horses would get very excited galloping over that wide expanse and at a certain point my pony bucked and I was flung to the ground. My brother wanted to disown me when I announced through my tears that I had wet my pants. Whether or not I had hurt myself was a minor concern. Brothers!

Then my father began to take me every Saturday afternoon to a riding-stable near Headington, just outside Oxford. I remember that we had lessons there too, but in a big open field. Once our instructor wanted to demonstrate how to go over a jump and she fell off. Heartless children as we were, we all thought this was very funny. It was at this riding-stable that I met Abbie, a sturdy bay, half-thoroughbred, half New Forest pony. She was a forward-going, comfortable ride and I fell in love, as girls do. I begged my father to buy Abbie and he finally did, for sixty pounds. (I could wrap him round my little finger.) Pony-mad as I was, I was in my seventh heaven.

I had just finished my day-school and during the long summer holidays I rode almost every day. We wandered round the woods and fields with Sooty at our heels, and had some splendid gallops down by Mokoe farm. Or I would go along the drive and ride down to Otmoor, a wild, swampy area on the other side of the village. At the gateway stood a thick holly bush, and I would thrust my riding hat into it as I passed. After my ride I would retrieve it and put it back on my head for my parents to see as I approached the house. I’m not saying this was a clever or sensible thing to do, just that I did it. I’ve always hated wearing things on my head, and have only now at the age of seventy begun to wear a riding-hat regularly (well, most of the time). We are more safety-conscious now.

The idyll finished when I went to boarding school at the age of thirteen. Abbie spent her time in the field behind the house. (It was the same field that featured in the film A Man for All Seasons filmed many years later. Henry VIII and Sir Thomas More strolled, discussing affairs of state, among the buttercups where my pony had grazed.) She was regularly fed during the winter months, but there was no one to ride her. When I came back to the hotel after thirteen weeks of term I found that she had changed, as she had hardly been handled at all during my absence. She had always been difficult to catch and now it was well-nigh impossible to do so. I used to get within a few yards of her, holding out a bucket of oats, and then she would wheel round and gallop away, kicking her heels up into the air. Sometimes three or four of us could catch her only by trapping her in a corner of the field. When she realized the game was up she would come quietly and allow herself to be led to the stable. But catching her was not the only problem. She had always been headshy and now I could no longer manage to bridle her without Wilma’s help. Once, I remember she escaped and my mother valiantly tried to stop her running along the village lane by hanging on to a dangling stirrup. Later I described the incident to my father, telling him that my pony had galloped away with her nostrils ‘diluted’.

I still had some happy rides with Abbie. Twice we went hunting but only twice, as usually the meet took place far from our village and we had no horsebox to carry her there. My memory of the hunts is not very clear, but I remember galloping for what seemed like ages with about fifty horses beside me. I lost complete control of my pony and concentrated at least on staying on her back, which I managed most of the time, though I did take a couple of tumbles. Luckily jumping hedges was not required, as a huntsmen held gates open for the younger or less experienced riders to rush through. Once the gate began to close as I passed through it and I caught it on my knee. I was blinded with tears as I galloped on, but by some miracle no permanent damage resulted. On my second hunt I was the only child present at the kill, which, luckily, I did not actually witness. I was awarded the tail, oops, the brush, and rode proudly home with it dangling bloodily over my horses’s neck.

So I did go hunting with Abbie but soon I began to have problems with her. Of course I considered myself to be a good rider at the time, but I realize now that I was far from being one, having had very little tuition. Left so much to her own devices during term-time Abbie began to cultivate some nasty tricks. Apart from being difficult to catch and bridle, she began to buck. When a horse wants to buck the experienced rider feels it coming and stops his horse from pulling his head down. If the horse can’t get his head down he finds it difficult to kick his heels up into the air, so the naughtiness is thwarted from the start. But Abbie had an unusual kind of buck: she would twist her head in the direction of her heels, so the buck was not a simple up-and-down movement, there was a violent sideways lurch as well. If she didn’t unseat you at the first buck she would try again, until she finally got you off. And the more often she succeeded, the more she developed a liking for the trick.

We had a lady staying at the hotel at the time called Mrs. Rose. Actually, I don’t think she was a Mrs. at all, gossip had it that she was not married but had come to the hotel to pass her pregnancy in secret. People were much more prudish in those days. She was very friendly towards me, perhaps because at that age I was little interested in gossip. She was an experienced horsewoman and came out into the field behind the house.

Attitudes to fox-hunting

Nowadays a lot of people are against hunting, as they consider it cruel. I can see their point, but I was not concerned at the time. When you live in the country you are more used to the death of animals: I had killed those baby foxes, not with pleasure, certainly, but I knew it had to be done. On the farm behind the hotel we reared pigs and chickens, and I took for granted these had to be killed for the table. Our dogs regularly killed rabbits when we took them for walks and we thought nothing of it, as rabbits were considered to be vermin. Foxes, particularly, were the farmer’s enemy as they would carry off hens and ducks even in broad daylight and we knew we had to get rid of them somehow. Another enemy was the grey squirrel, and I remember that the government would pay you a shilling for every tail you handed in. Rooks too had to be shot, as they would eat up the seed you had just sown. I loved animals and cried buckets years later when Sooty was run over at the age of fourteen. (He had gone out on some amorous expedition, so you could say that he had died doing what he loved to do.) But the death of a fox didn’t upset me at all.

A lot of people are against hunting because they consider it the prerogative of the upper classes, but generally this is not true at all: the fact that I took part as a fourteen-year-old, the daughter of parents with little means proves my point. Anyone could take part, as long as they and their horses were well turned out and paid their dues. Many of the riders were local farmers, who could certainly not be excluded for social reasons as for most of the time we were riding over their land. Some hunts may be exclusive but most are not. My problem is that though I understand the reason why many people oppose foxhunting, I support it also because it is part of the countryside tradition. Since the hunting with dogs ban was passed in 2005 there are more people joining hunts than ever, so they obviously agree with me.

“Try putting Abbie into a fast gallop,” she said. “Horses can’t buck if they are going flat out.” So, full of confidence, I set off at a brisk gallop. When we had got up speed Abbie launched a huge buck and I went sailing into theair. She then swerved so close to Mrs Rose that the poor lady fell over. I was so afraid that she might give birth on the spot that I forgot my bruises as I scrambled back to my feet. Luckily the baby did not emerge until a couple of weeks later, in hospital in the regular way.

One day I went riding along the lane past Honor’s farm. At the T-junction at the end of the road I turned into a field for a canter. Abbie did one of her screw-bucks and I fell heavily on to one arm. I felt a sharp pain in my wrist. As I got slowly up I saw Abbie galloping off towards home. I got up and began to follow her, cradling my wrist. After half a mile I found Abbie tied by her reins to a fence beside the road. I managed to mount her and rode slowly home, my wrist throbbing. A car with a couple inside stopped beside me. “Are you all right?” said a kind voice. It must have been the person who had tied Abbie up. “Yes,” I said curtly, without even thanking them, and they drove off. I feel guilty to this day that I didn’t thank them. My only excuse is that I was probably in shock.

As soon as I got home I put the pony away and went to the bathroom. For ten minutes I stood with my wrist under the tap, hoping that the cold water would make the swelling go down. It didn’t. I lingered in my room for a while. I didn’t want to tell my parents that I had hurt myself because it reflected on Abbie and I was afraid they might want to sell her. But finally I had to go to them and tell them what had happened. I ended up with my arm in plaster.

Of course riders expect to injure themselves some day or other. This was not my first fracture, anyway. When I was ten I had been playing billiards with a schoolfriend. The table was a heavy mahogany one, constructed within a frame: if you turned it over it became a pingpong table. But it hadn’t been latched properly, and as we were playing it began to swing round of its own accord. As the balls began to fall on to the floor I put up my hands to stop it. But the table was heavy and crashed down, imprisoning my arms. My friend ran all the way through the big house to fetch my father, who came running, big man though he was, and eased my arms out of the trap. One arm was broken, the wrist on the other arm badly bruised. I don’t remember the pain, but recall the pleasure I had when my big brother came to my bedside to read to me. I even remember the book, Told on the King’s Highway, a collection of stories from medieval literature. The kindness shown by an elder brother who usually ignored me was more memorable than the pain.

But somehow the riding accident turned out to be more traumatic. When my wrist was better I went confidently out to the field to catch Abbie and I suddenly found myself shaking and sweating. In my head I wanted to ride, but my body resisted. From then on I rode only reluctantly, always finding some excuse not to go out. When I did ride I only walked and trotted, as the very idea of cantering made me feel even more apprehensive. When my parents realized what had happened they asked a client, who was also an amateur jockey, to ride the pony. He did so several times, and found that she was an excellent jumper, clearing five feet with ease although she was slightly under fourteen hands. However, on occasion she managed to buck even him off.

When I went to boarding school and spent weeks away from home Abbie spent more and more time alone in her field. Then one day my father wrote to me asking gently if I would like him to sell her. At first I protested warmly, then I agreed it was the best thing to do. When I came back from school and saw the field empty I burst into tears that expressed relief as well as sorrow.

I think that when I opened a riding centre so many years later I was never impatient with people who were apprehensive when they started riding, or even when they were experienced riders. I had been through it all myself, and knew that the fear was not always rational, but very real all the same.

The next few years of my life were taken up with school and university. The only time I went riding during that time was when I went to a riding-centre with a boyfriend. It was Sunday morning and most of the horses were booked. “There are two left,” a stable girl told us, “one bucks and the other bolts.” Mike took the bucker, which, true to its reputation, bucked continuously, even at a walk. I realize now that it might have had a back problem. As for the bolter, we decided that when we returned to the stables we would go only at a walk, as horses usually bolt towards home, not away from it. So we got back to the stables without incident. I realize now that it was very foolish of the riding-stables to give such horses to a couple of riders whose ability they had not bothered to check. This wouldn’t happen nowadays as we are more safety-conscious also in this respect.

This was my only riding experience during three years at Oxford University. One would deduce that my childhood passion for horses had faded away. It was to be revived in an unexpected place: Italy. After taking my degree in French and Italian in 1964 I went to Florence for a year as ‘reader’ at an Italian secondary school. This meant that I had to stand beside the teacher during lessons and read from the text-book when required. Sometimes I would have to ask the students questions. I enjoyed the work but found the salary barely enough to live on, as I had to pay the rent of a flat as well as feed myself, so I took a second teaching job at the British Institute, a well known language school in Via Tornabuoni, the most fashionable street in Florence. Of course, like most young English people starting to teach for the first time, I imagined that I could teach my language to Italians simply by virtue of being able to speak it. I soon discovered my mistake: I had to see my language from a completely different viewpoint, that of an Italian pupil, and learn to teach it step by step. Luckily my text books served as a guide. Nowadays, of course, you have to take exams in teaching English as a foreign language. Then you needed only to speak ‘Queen’s English’, as it was called then, to be accepted by the school director.

I found that I loved teaching, and accepted a post at the British Institute for the following year. I had by this time made friends with a group of young artists. They were pupils of Pietro Annigoni, and we would meet the great man every Tuesday for lunch at a trattoria in Via Santo Spirito, on the south side of the Arno river. Then in the evenings just the young people used to meet for supper at a trattoria called Oreste’s in Piazza Santo Spirito, the square round the corner. Often we would spend our free time together. One day Nando, my boyfriend, said: “At San Donato-in-Collina there’s a ranch: let’s go riding!” And though I was the only one in the group who had actually ever sat on a horse, that’s what we did.

CHAPTER 2

Riding in Tuscany

To get to the ranch we had to drive a few miles out of Florence and then take a steep, dirt road that zigzagged uphill to a long ridge, at one end of which was a farmhouse with a bar and restaurant and behind it the stables, all rather ramshackle but with a friendly atmosphere. The place was run by Benito, a skinny, jovial fellow dressed as a cowboy. I don’t think I ever saw him without his wide-brimmed cowboy hat and a checked scarf knotted round his neck. We were handed a horse each and allowed to go off by ourselves. No one thought of asking whether we knew how to ride. Possibly it didn’t matter very much with those docile animals, used to constant changes of rider. I don’t remember any of us ever falling off, which was lucky, as the ground there was very stony and a fall could have been disastrous. We didn’t wear hard hats, of course. To tell the truth it had never even occurred to us to acquire them.

Sometimes I would go to the ranch alone, taking the bus to San Donato and then walking up the stony track. On occasion I would even stay the night. We all slept on mattresses in a single room, so I think the family must have been very poor. Like many poor people they were very hospitable and they soon treated me like one of the family.

It was at San Donato that I acquired my first dog. There were a lot of dogs there, I expect they were strays that had been taken in: hospitality was extended to them too. One day three or four of them began to fight. In an attempt to divide them I threw myself into the fray and managed to get bitten in the arm. When the fight was over Benito said: “It’s the fault of Dick, that black hairy dog, he’s the attaccabrighe, the quarrelsome one. Perhaps you would like to have him?” I had been longing to have a dog to keep me company in my little flat in Florence and I accepted at once. Benito gave me a length of string and Dick and I walked together down to the bus-stop. Luckily I was able to take him with me in the bus for a small extra charge.

Dick is a common name for dogs in Italy, as I don’t think Italians know that the word has a secondary meaning. Another common name is ‘Black’: I knew an almost white English setter with that name. A neighbour of ours had a male alsatian called Lassie... Anyway, I looked in my Shakespeare glossary and found the name ’Michie’, which meant a truant and sounded satisfactorily black and hairy. Michie was to be my companion for another sixteen years.

I can’t say that I liked everything that went on at the ranch. I had begun to ride Pedro, a horse that was kept at livery there, and he was a fine, gentlemanly fellow that gave me many a happy ride. His owner allowed me to go out alone on him and I did so with much more confidence than when I had ventured out with Abbie. But I could not help noticing that a lot of the horses at the ranch were overworked. During the season they were saddled up in the morning and were ridden till dusk by various groups of riders, usually young men. I remember once seeing a group come galloping home along the stony road where I was accustomed to travel at a cautious walk. When the horses reached the ranch they stood with their sides heaving and sweating so much that the sweat formed puddles on the ground under their bellies. The riders paid and then another group of lads jumped on and galloped away, not giving the horses even the chance to get their breath back. One of them I had already noticed was lame. Benito himself once said to me: “During the season a horse lasts me about a month.” In fact I once saw a sleek five-year-old bay arrive, prancing as he descended from the van. A month later he was taken away with a group of other horses, his head hanging down and his ribs showing, straddling his legs to stop himself falling down. In the centre of his spine, now sadly evident, was a sitfast, a hard growth caused by an ill-fitting saddle. I think all the saddles there were ill-fitting, as I often saw horses with bad saddle sores. Certainly the equipment was never cleaned or mended.

I am glad to say that a riding-centre like Benito’s ranch could not exist any more. Thank goodness that people are more sensitive about cruelty to animals than they were then, and no doubt the Italian equivalent to the RSPCA would have forced the place to close. You may ask why I went there myself. One reason was that there was at the time no alternative, another was my affection for that aimiable rogue Benito and his family. Of course I saw that the horses were overworked in the summer, but we went riding mostly in the cooler seasons when the horses were in better shape. And we didn’t ride fast, the terrain did not permit it it, nor did the abilities of my companions. Most of the time we simply ambled.