35,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Crowood

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

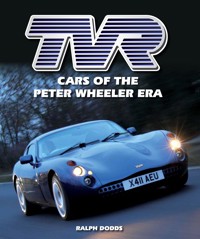

For nearly sixty years, TVR produced some of the most thrilling, spine-tingling, hand-built sports cars to emerge from any British motor manufacturer. Yet it was the period between 1981 and 2004, under the management of Peter Wheeler, when the company finally shook off its shed-built roots and proved that it could produce cars that could match anything from Maranello or Stuttgart in terms of performance, but at a fraction of their price. Illustrated with over 300 photographs, TVR - Cars of the Peter Wheeler Era tells the story of the design, development and engineering of some of TVR's fastest, outrageous and most successful cars, from the retro-styled S1, to the racing Tuscan, 1000bhp Speed Twelve and the brutal Sagaris.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 392

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Ähnliche

CARS OF THE PETER WHEELER ERA

RALPH DODDS

THE CROWOOD PRESS

First published in 2015 by

The Crowood Press Ltd

Ramsbury, Marlborough

Wiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book first published in 2015

© Ralph Dodds 2015

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 84797 998 8

Disclaimer

Every reasonable effort has been made to trace and credit illustration copyright holders. If you own the copyright to an image appearing in this book and have not been credited, please contact the publisher, who will be pleased to add a credit in any future edition.

The word ‘TVR’ and the TVR speedline logo are registered trademarks of TVR Automotive Limited and are used with permission.

CONTENTS

Acknowledgements

CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION – THE WILKINSON AND LILLEY ERAS

CHAPTER 2 A NEW HAND AT THE HELM

CHAPTER 3 V8 POWER

CHAPTER 4 BIG BAD WEDGES

CHAPTER 5 A NEW SHAPE FOR A NEW ERA

CHAPTER 6 GRIFFITH – A DESIGN ICON

CHAPTER 7 CHIMAERA – A TVR FOR THE MASSES?

CHAPTER 8 FROM SPORTS CAR TO SUPERCAR

CHAPTER 9 THE TUSCAN RETURNS

CHAPTER 10 END OF AN ERA

CHAPTER 11 COMPETITION: FROM CLUBMAN TO LE MANS

CHAPTER 12 PROTOTYPES, ONE-OFFS AND OCCASIONAL INSANITY

CHAPTER 13 TVR – THE FUTURE?

References

Index

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

When Crowood first approached the TVR Car Club to seek out an author to write the history of TVR during the Peter Wheeler era, I had no idea that the task would eventually fall to me. But after a fairly lengthy discussion, I was persuaded by members that I had the level of knowledge to do the subject justice. I must thank them for their support throughout this task, especially David Hothersall, who kindly read my drafts and highlighted the errors.

I must also thank those members of the TVR Car Club and other TVR enthusiasts who have kindly provided their photographs for this book, without which it would be a very monochrome publication. In particular I am indebted to Andy Hills (www.myfavouritephotos.com) whose superb photographs feature throughout this book. Other thanks must go to: James Agger, John Baillie, Andrea Bennett, Norman Bland, Stuart Bowes, Matt Bristow (www.rubberduckdoes.com), David Bruce, Tony Connor, Harry Cottrell, Tony Cottrell, Ian Dally, Richard Dredge, Oliver Edwards, Jasper Gilder, Trevor Goodlad, Ralph Gosden, Clive Harding, Gary Harman (www.garyharman.co.uk), Tony Hodgson, Newton Holmes, Dave Howard, Keith Hume, Paul Jackson, Nick Kay ([email protected]), Rupert Kent, David Lord (www.davidlord.co.uk), Steve McAllorum, Damian McTaggart, John Millington, John Morris, Noel Palmer, Tim Payne, Ian Renwick, Marc Scorer, Alan Smith, Paul Smith, Mike Spencer, Robert Steele, Adam Victory, Chas Whitaker/Str8six Ltd, Wiktor Wilczynski, Nick Williams of NWVT.co.uk, Simon Williams, Tim Woodcock and Chris Wright. These photos would not have been possible without in some cases people being willing to drive their cars all over the country. I am especially indebted to David Ancill, Nigel Lewis, Steve Perkins, Barry Stanton and Andrew Thorp who kindly brought their cars to Beaulieu for a photo shoot (with thanks to the National Motor Museum at Beaulieu and photographer Tim Woodcock).

I am also deeply indebted to those former members of the workforce of TVR who have gone out of their way to provide me with information. In particular I must thank Martin Lilley, Damian McTaggart, John Ravenscroft, John Mleczek, John Reid, Trevor Cooper, Dave Legg, Chris McGuire, Mike Vernon, Mike Williams, Paul Forrest and Heath Briggs. And I should like to thank the new owner of TVR, Les Edgar, for his encouragement and permission to use some of the old TVR Engineering images.

I must of course also thank my family, wife Fiona and children Scott and Emma, whose patience has been unparalleled over the past eighteen months while I have been writing this when I should have been doing other tasks around the house. Your support has made it all worthwhile. Equally I am thankful to Hannah Shakespeare and Emily Simpson at Crowood for the support and advice they have given me in writing my first book.

Finally, I must thank the great man himself. Although sadly he is no longer with us, Peter’s legacy lives on and without his vision, determination and, at times, sheer bloody-mindedness, I would have had nothing to write about. So Peter, I thank you for saving TVR from the brink in 1981 and building some of the greatest cars the world has ever seen.

TIM WOODCOCK

CHAPTER ONE

INTRODUCTION – THE WILKINSON AND LILLEY ERAS

Ever since Karl Benz patented the world’s first true automobile in 1886, a relatively small number of car manufacturers have emerged whose products really fire the passions of not only those who are sufficiently privileged to own them but also those who can only gaze from afar. They might not generate envy in quite the way that, say, a Porsche 911 or BMW M3 can, but they can nevertheless cause heads to turn. Almost anything coming from the stables of Enzo Ferrari, Ettore Bugatti or Charles Rolls and Henry Royce would normally fall into that category, as would some specific models such as the classic Jaguar E-Type, the Lamborghini Countach and Maserati Birdcage. And then there are the manufacturers whose cars achieve that same cult status during a particular period, most usually following a change of ownership, such as Aston Martin, whose products since the arrival of David Brown in 1947 are recognizable throughout the world. It is in this latter category that a relatively small Blackpool-based manufacturer of hand-built sports cars falls.

For although TVRs have been produced in Blackpool since that same year that David Brown arrived at Aston Martin, it was from 1981 onwards, after the company was acquired by Peter Wheeler (also known by his initials PRW and referred to as such throughout this book), that they became instantly recognizable, causing young boys’ heads to snap round at a hundred paces. Nowadays, thanks to PRW’s legacy, TVR has a huge worldwide following. PRW produced some of the most iconic cars ever seen, such as the Griffith – for which TVR received the Design Council’s British Design Award in 1993 – and the utterly outrageous Speed Twelve. This is the story of the cars he built.

The most popular TVR – a Chimaera resplendent in Halcyon Midas Pearl, seen here at Beaulieu House. This example has the larger 5-litre engine. TIM WOODCOCK

The ultimate production TVR, the Sagaris. ANDY HILLS

Although the PRW era started in 1981, the TVR story began nearly sixty years earlier on 14 May 1923 with the birth in Blackpool of Trevor Wilkinson. His parents were shopkeepers and young Trevor lived much of his early life above the family shop, but it soon became clear that Trevor, who was academically bright and gifted with his hands, was destined for greater things than merely running the family business.

Trevor loved anything mechanical and as a schoolboy in his spare time he would turn his hand to repairing the prams and buggies into which his parents’ business had expanded. He left school at fourteen to pursue his love of engineering, starting an engineering apprenticeship with a firm close to the family home on Blackpool’s South Shore. Little did he know then, but these early experiences would result in his founding a car company that would, in his lifetime, produce some of the most stunning sports cars ever built; cars to rival iconic marques costing as much as ten times more. It is undoubtedly a great shame that Trevor, a modest, humble, diminutive figure whose vision it was that set the DNA for TVR for years to come, would benefit not a single penny from its later success. Yet without his initial energy, enthusiasm, determination and imagination, none of this would have happened.

In complete contrast, PRW was a tall, confident businessman who, having studied chemical engineering at Birmingham University, entered the burgeoning North Sea oil industry in the early 1970s and had made his first million before he turned thirty in 1974. Like Trevor, he was an engineer at heart and they both shared a deep passion for everything automotive although, perhaps surprisingly for someone with a background in chemical engineering, PRW hated a tidy workshop. ‘He believed if you had enough time to clean the workshop, you weren’t working hard enough!’ recalled PRW’s motor sport chief, John Reid.1 If Trevor was the inspiration behind TVR and gave the firm its name, it was PRW who turned that inspiration into one of the world’s most desired marques and gave it models that competed bumper to bumper with those from the likes of Ferrari, Porsche and Maserati.

There is something almost unique about TVR. Almost unique, because this special quality is shared with a very select group of other marques, such as Ferrari and Rolls-Royce, whose cars rule not the head but the heart, whose spirit can be traced back through their history. Throughout TVR’s history, but perhaps especially so during the PRW era, as former chief engineer John Ravenscroft observed, ‘TVR were different enough and outrageous enough to command a bit more money.’2 This was the DNA that flowed through the marque, linking the early cars with the most recent; a certain something that causes the heartbeat to rise just a little even before one gets into a TVR. It is important to recognize that at the heart of any Chimaera, Cerbera, T350 or indeed any TVR of the PRW era, what really makes them special is that link to Trevor’s earliest specials. To do justice to the cars of the PRW era, one must take a brief look at TVR’s early history.

THE TREVOR WILKINSON ERA (1946–62)

The initial years of TVR are well documented in other books. Students of early TVR history would do well to read Peter Filby’s three volumes, TVR: Success Against The Odds,3TVR: The Early Years4 and TVR: A Passion to Succeed.5 But this book is a stand-alone volume so, although it is not the intention to repeat much of what Filby has said, given the importance of understanding how the lineage shaped the later cars, this chapter provides a brief overview.

Trevor celebrated his sixteenth birthday in May 1939 just as Britain was teetering on the abyss of the Second World War. Unlike most of his generation, he was not called up for active service – Filby suggests there may have been a medical issue6 – so he was able to complete his apprenticeship and return to work in the family business. However, this did not offer Trevor the engineering challenges that he sought and, once the war was over, his time came. In 1946 the fully apprenticed mechanic persuaded his parents to purchase a half share in a new engineering venture, an old wheelwright’s workshop at 22 Beverley Grove, Blackpool. Trevcar Motors was born.

TVR No.1 and No.2

‘Trevcar’ did not last long. In 1947 Trevor took three letters from his Christian name and renamed the company TVR Engineering Ltd. In the same year he completed work on the rebodying of the stripped-down chassis of his Alvis Firebird. Although he drove it for a short while, he soon sold it to realize capital to fund the build of his first original car, TVR No.1. He was joined by his long-time friend and fellow engineer Jack Pickard to try to grow the business and provide sufficient cashflow to fund this project. Unlike the Firebird project, which retained the Alvis’s chassis and running gear, TVR No.1 incorporated Trevor’s own-design, multi-tubular chassis with running gear derived from a number of different sources including springs from a Blackpool fairground ride. TVR No.1 was sold as soon as it was completed but sadly the new owner promptly crashed the car and it was largely destroyed.

Where it all began. Trevor Wilkinson (right) with Jack Pickard at Beverley Grove in 1999 (the blue door behind Jack is the original entrance to Trevcar Motors). CHRIS WRIGHT

Trevor was determined that this would not be a major setback and set about designing No.2. It was slow work because their time was focused mainly on the light-engineering tasks that provided the finance for car development. Soon, sufficient funds were accrued to enable the build of TVR No.2 to commence. Completed in 1949, it is still in existence today and is the oldest surviving TVR.

Trevor continued to build occasional one-offs and specials for the next few years until 1954 when he started his first series model. Using the same principle of a multi-tubular chassis mated to a lightweight body, the TVR Sports Saloon was launched with a glass reinforced plastic (GRP) body sourced from RGS Atalanta. Trevor supplied purely to customer order and the bespoke nature of TVRs was born. Essentially, he would build as much or as little of the car as the purchaser demanded, from complete cars down to kits with or without engines. He engaged with every customer, and this practice continued until the company entered administration over fifty years later – customers were encouraged to talk to the factory staff about their requirements and even to visit to see their car in production.

In 1957, Trevor made a fundamental change to the TVR design. Although all TVRs since No.1 had used a multi-tubular chassis, the early cars were largely two-dimensional affairs in which the body sat on top of the chassis as in traditional ladder-style, chassis-body arrangements. The change that Trevor conceived, which was very clever, was to arrange the main structure in four longitudinal tubes forming a central backbone with extensions on which to hang the engine and suspension with outriggers to support the body around the passenger compartment. The benefit was immense, for not only was the chassis much stronger but it also lowered the centre of gravity, which improved the handling. This basic design has formed the chassis for every subsequent TVR.

TVR NO.2 SPECIFICATIONS

Engine

Ford E93A side valve with twin

SU carbs

Capacity

1172cc

Power

c.90bhp

Torque

60lb ft

Top speed

c.90mph (145km/h)

Suspension

Fully independent front and rear

Brakes

Drums all round

Wheels and tyres

24in Avon

TVR NO.2

RICHARD WRIGHT

After responding to an advert in Autosport in 1966, my father purchased TVR No.2, registration FFV 62. At that time, the car was still racing in the 1172 Formula and, although road legal, was still in its race trim. Along with the purchase came a box full of spare parts – including an Aquaplane head, which was used when hill-climbing and sprinting.

I acquired No.2 in the early 1990s and embarked upon a three-year period of restoration. Trevor was instrumental in the process and provided me with invaluable data and advice from his home in Menorca.

Some interesting facts emerged from my correspondence with Trevor; for instance, he told me that after TVR No.1 was destroyed in an accident, he used some of the tubular chassis, rails and other parts to build No.2 including a tachometer from a Supermarine Spitfire. Therefore, in some ways, No.2 is an embodiment of the very first TVR.

Further to this, I sent Trevor a colour chart, for him to pinpoint the precise colour. I also used an array of specialists during the restoration period. One of these specialists was Eric Marsden, who handmade the aluminium panels for Aston Martin. To watch and learn from this man at work was a real privilege.

When the restoration was complete, TVR No.2 won various awards, including the inaugural Trevor Wilkinson Trophy, awarded to the best restored TVR in the previous twelve months, the trophy being handmade by Trevor himself to commemorate the fiftieth anniversary of the forming of the company. It was the theme of various documentaries, books and magazine features and has also been exhibited at venues such as the NEC and Le Mans.

I have been fortunate enough to race TVRs, some over 400bhp, and I very much consider No.2 a unique driving experience, which must have been well ahead of its time. The steering is very positive, giving excellent handling at speed. It has large drum brakes, which were probably designed for a vehicle twice the size of No.2; therefore, coming to a stop is instant. It also runs twin SU carburettors, with a bespoke free-flow manifold. This, combined with the low weight, results in a surprisingly high performance, with no synchros in the gearbox and double de-clutching adding to the fun!

TVR No.2 at Wells in 2004. TONY CONNOR

Jomar and Notchback Coupé

One of the very rare surviving Notchback Coupés, seen here at Rockingham for the TVR diamond jubilee celebrations in 2007. ANDY HILLS

The first car to be fitted with this chassis, which was also TVR’s first with independent front and rear suspension, was destined for Trevor’s first American customer, racing driver Ray Saidel, who was soon to become synonymous with TVR’s rise. The body, which was in fact two front halves of a Microplas Mistral body sandwiched together, became known as a Jomar, named (according to author Graham Robson7) after Saidel’s children, John and Margaret. While the Jomar was not in itself a huge success, selling only a handful of cars, it opened up a new market for TVR in the United States where a significant percentage of orders would originate for the next twenty years. Furthermore, the same chassis underpinned the new ‘Notchback Coupé’, which was TVR’s first in-house body.

The coupé was the first car to be built at the new Hoo Hill works. Trevor and Jack had outgrown Beverley Grove and, with a relatively healthy order book and new finance available, they took the plunge and moved into the old brickworks. Orders continued to arrive from Ray Saidel, who became TVR’s first US distributor. On face value this was excellent news; however, Trevor and Jack were good engineers but poor businessmen and they had not fully considered the implications of such a rapid overseas expansion. Two new directors, Bernard Williams and Fred Thomas, were brought on board to handle the business aspects, leaving Trevor and Jack to concentrate on another new model.

Grantura

The Notchback Coupé was smoothed out with the rear being streamlined and raised to produce the first TVR of a line that would effectively end with the launch of the wedgeshaped Tasmin in 1980. The Grantura was offered, like previous cars, with a choice of engines, although the earliest cars predominantly used a twin-carburettor version of the 1200cc Coventry Climax engine producing just over 80bhp. In March 1959 Autocar was the first national magazine to publish a TVR road test, which, as Robson has noted, ‘set the seal of respectability on the Grantura’ by publishing ‘one of their famous cutaway drawings showing the complexities of the chassis’.8

By 1959, the company had had yet another name change. The engineering versus business debate had resulted in a healthy order book but almost non-existent cashflow. TVR Engineering became Layton Sports Cars. Shortly afterwards, a second company, Grantura Engineering, was formed to separate sales from design and development. Grantura Engineering performed well, producing a number of improvements to the Grantura, but Layton continued to struggle. The lucrative US market was lost for a while when Saidel withdrew his support following Layton’s failure to supply the numbers he required.

As the 1960s dawned, John Thurner joined from Rolls-Royce to become engineering director while Manchesterbased TVR dealers Bernard Hopton and Ken Aitcheson took over the reins as the name changed again to TVR Cars Ltd. Trevor’s influence had been irrevocably eroded and he felt that he had no choice but to resign in April 1962.

This was timely. A hugely expensive but ultimately fruitless Le Mans campaign just two months later, coupled with the apparent loss of financial control by the remaining directors, led to TVR Cars ceasing to trade in October 1962. However, the decision taken three years earlier now proved to be incredibly fortuitous, for Grantura Engineering, together with its subsidiary Grantura Plastics, continued to build and sell TVRs.

The original TVR winged badge, seen on a Mk I Grantura. ANDY HILLS

Trevor Wilkinson tries out a T350c for size in 2003 – still the same basic concept as the cars he built all those years ago. TONY CONNOR

The Mk III, which used a new Thurner-designed chassis, had been launched in April 1962 and gained an 1800cc MGB powerplant the following year before a new rear end was developed incorporating Cortina Mk I ‘ban-the-bomb’ rear lights and a higher, truncated ‘Manx’ tail; these cars dropped the Grantura badge to become the 1800S. Though they did not know it at the time, this styling exercise hugely improved the handling as the cut-off tail markedly reduces lift, especially at high speed, which was proven in the much later T350s.

Griffith

The year 1963 also saw the birth of the now legendary TVR Griffith. The popularly accepted story – disputed by some – is that US dealer Jack Griffith transplanted the 195bhp 4.7-litre Ford V8 from Mark Donahue’s AC Cobra into TVR importer Gerry Sagerman’s Grantura and in doing so set the stage for TVRs to be equipped with huge engines and stunning performance. Prior to this, TVRs were quick but they were never going to challenge the might of Ferrari, Porsche or Aston Martin in a drag race. With the new Griffith 200 – a Mk III Grantura with a Ford V8 engine – they had a car whose performance Peter Bakalor described in Modern Motor9 as ‘shattering’, while John Bolster tested the car for Autosport10 at an astonishing 163mph (262km/h). This compared with just 114mph (183km/h) by the same test driver for an 1.8-litre Grantura Mk III.11 As Robson records, in straight-line performance the Griffith ‘was good enough to embarrass severely an E-Type Jaguar and many V12-engined Ferraris’.12

The vast majority of Griffiths – both in 200 form and the later 400, which had the Manx tail and an even more powerful 271bhp Ford Mustang V8 – were built without engines/gearboxes for export to the United States where Jack Griffith’s team fitted the powerplant. Sales were brisk, at one point in 1964 peaking at fifteen cars per week, which would not be matched again until the Chimaera in the late 1990s, but this in itself was to be the car’s downfall. Put simply, Grantura Engineering’s quality control could not support this level of production and Griffith’s engineers spent increasing amounts of effort correcting the poor build quality – most notably overheating – and responding to customer complaints.

A US dock strike in 1965 was the final straw that broke Grantura’s back, with the engineless Griffiths being lined up at the docks with no means for them to be cleared through customs; understandably Griffith had not taken delivery of the cars, so refused to pay his UK supplier. The banks grew increasingly frustrated and, in the autumn of 1965, foreclosed on the business. Yet another bankruptcy, but this time the resurrection would trigger a significant change in fortune.

THE LILLEY ERA (1965–81)

Although most Griffiths were built for export with only a handful sold in right-hand drive, one prominent UK-based customer was a gentleman named Martin Lilley. Martin had spent his spare time while at college studying engineering building and preparing race cars, predominantly Lotus. But he was closely involved with the Barnet Motor Company (BarMoCo), which later become the TVR Centre, and after some successes with Lotus and then an E-Type, Martin bought his first TVR, a Griffith 400.

The popular story suggests that his car was in Blackpool for repair at the time that Grantura Engineering went into liquidation and that it was in order to release the car that Martin and his father, Arthur, bought the company. However, Martin’s recollection of this story is very different, in that the Griffith had been repaired and returned well ahead of the liquidation.13 His father had recently bought from a friend some shares in Grantura Engineering that were of course effectively worthless once the company went into liquidation. Martin’s car-building was a hobby but he had always wanted to venture into manufacturing; this would give him that opportunity. Arthur Lilley engaged with the liquidators and, following negotiation, ownership of the remaining assets of Grantura Engineering changed hands for the sum of £12,000. The new company was formed on 30 November 1965 and regenerated the old name: TVR Engineering Ltd.

Four of the key figures in the early history of TVR come together at the 1997 golden anniversary celebrations in Blackpool. Seen here at the former Hoo Hill works are (from left to right) Martin Lilley, Trevor Wilkinson, Jack Pickard and Joe ‘the Pole’ Mleczek. AUTHOR

The Lilleys viewed that the key to making TVR a success would be to concentrate initially on improving build quality. Put simply, if less effort were expended on warranties, cashflow would improve, as would the balance sheet, which in turn would free up resources for investment. So the first Lilley TVR was an improved 1800S, known as the Grantura Mk IV, of which some thirty-eight models were sold in 1966–67. In order to ensure profitability, prices were increased by about 30 per cent to just under £1,000 for the customerfinished variant and nearly £1,300 for an ex-works car.

Vixen and Tuscan

An extremely rare and immaculate right-hand drive Tuscan SE. TONY CONNOR

The Grantura was replaced in 1967 by a new model, the Vixen. Although the Vixen was very similar in many respects to the Grantura Mk IV, the MGB engine was replaced with a 1600cc Ford Crossflow which, although slightly less powerful than its predecessor, was markedly lighter and, most importantly, cheaper. The combination of less power versus reduced weight meant that performance was roughly comparable with the Grantura although it is interesting to note that Autocar, in an early road test, recorded a maximum speed of 109mph (175km/h) against just 101mph (162km/h) for the Grantura;14 other contemporary publications had tested the 1800S at up to 114mph (183km/h).15

Martin and Arthur also recognized the need to maintain the flagship V8 and thus the Tuscan continued the Griffith tradition. Ostensibly, a Tuscan was a rebadged Griffith 400 with an improved cooling system, a more luxurious interior and the ‘cooking’ 195bhp engine, while the Tuscan SE had the wilder 271bhp unit. Sadly, a name change was insufficient to rid the car of the Griffith’s reputation for poor build quality and in the first half of 1967 TVR averaged just over one Tuscan per month. While reputation was one key reason for this, the other was price: while a Tuscan could seriously embarrass an E-Type Jaguar in terms of performance, the Jaguar was the sports car to own in the late 1960s yet in most configurations it was cheaper than its Blackpool-built rival.

The solution to improve sales of both the Tuscan and Vixen was to look to a new range and thus, in April 1968, TVR launched the … Tuscan and Vixen! To be fair, the new models were actually badged Tuscan LWB and Vixen S2 and incorporated a brand new chassis some 4½in (11cm) longer and with a commensurate lengthened body. Performancewise, the Tuscan remained the car to beat, with Motor magazine testing Martin Lilley’s own car (an SE model) in May 1967 at an estimated top speed of 155mph (249km/h) – and possibly as much as 160mph (257km/h) – but they ran out of test track with the car still accelerating.16 They described the car as the ‘fastest ever … production car’ from 0–100mph and recorded a time of 0–100–0mph of just 18.5 seconds, markedly faster than a 450SE over twenty years later. Despite this, Tuscan sales remained relatively poor with just twenty-four LWB and twenty-one of the later wide-bodied variant built, most of which went for export.

In contrast, sales of the smaller Vixen started to develop quite quickly with over 400 being built between 1968 and 1970. In 1969 the company broke even for the first time since bankruptcy. The following year the Lilleys turned their first profit and they continued to do so for the majority of the 1970s. Martin later described this as his greatest achievement, turning the ailing company around and keeping it going for fifteen years.17

If the Tuscan V8 was built for export, the new Tuscan V6 was designed and built for the home market. Fitted with the Ford Essex 3-litre V6 from the Zodiac Mk IV and later the Capri, it plugged the performance hole in the middle of the range. Performance was sluggish when compared with its larger-engine sibling but still extremely rapid when compared with most of its peers. Motor magazine again ran out of test track when they assessed the car’s performance at the Motor Industry’s Research Association proving ground at Nuneaton. They had to brake as the car was accelerating through 118mph but estimated that 125mph (201km/h) was easily achievable; the benchmark 0–60mph was despatched in just over 8 seconds. In comparison, the most popular of the early 911s, a 1970 Porsche 911T 2.2, took nearly 9.5 seconds to 60mph and had only a marginally quicker maximum speed of 127mph (204km/h). The strength of the V6 really came in its price. At just £1,492 for a component car, and £1,930 ex-works including purchase tax, it was a veritable bargain compared with its rivals. Prices for 911s started at around £3,700 and even the humble Porsche 914/6 – which took a positively lethargic 12 seconds to reach 60mph and ran out of steam short of 120mph (193km/h) – was £3,475.

Unfortunately the Tuscan V6 had one major flaw. The Essex powerplant did not meet the strict US emissions regulations and therefore TVR’s biggest potential export market was effectively closed to it. Martin Lilley’s solution was to use another new engine, this time the 2500cc Triumph straight-six, which first appeared at the 1970 Earls Court Motor Show. The engine, which was equipped with twin Zenith-Stromberg carburettors as the fuel-injected version that powered European TVRs was equally unsuited to the US regulatory conditions, was neither as powerful as the Ford V6, nor the car as quick; but it did sell well in the United States, where there was no real alternative if one wanted a new non-V8 TVR. It took a leisurely 10.6 seconds to reach 60 and ran out of power at just 111mph (179km/h), but despite this it outsold the Tuscan V8 by a ratio of nearly four to one.

With sales of Vixens expanding and Tuscans steady and the rapidly filling order books for the US market, TVR was running out of space in the Hoo Hill works, which had spread out from the main building into a series of sheds. The Lilleys found a new site (originally built for Busman Sidecars but more recently home to a kitchen-appliance manufacturer) about a mile away in Bristol Avenue. Production was moved there over the Christmas 1970 shutdown period and TVR were to remain on this site until the doors finally closed in 2006. It was a good move. The site was not significantly larger than Hoo Hill – around 40,000sq ft (0.37ha) – but it was laid out much better, had more scope for expansion and was significantly more flexible. The decision taken in 1970 would pay dividends in the 1990s when TVR needed to produce up to 2,000 cars per year.

M Series (1972–79)

Midlands-based TVR dealer/engineer Mike Bigland had undertaken some serious modifications to the chassis of a customer’s Tuscan V8 to improve its competition handling and suggested to Martin Lilley that many of these improvements could be incorporated into an improved chassis for the next generation of TVRs. Martin challenged him to turn his theories into practice and he joined the team at Bristol Avenue to design a new chassis. Thus the M Series was born.

The M Series was an epoch moment for TVR for their fortunes began to turn rapidly. The cars, with a choice of 1.6-litre Ford Kent, 2.5-litre Triumph or 3-litre Ford Essex engines, were the mainstay of the range throughout the 1970s with nearly 2,500 cars being built between 1972 and 1979. The main difference was the introduction of squaresection chassis members, thicker gauge steel and increased cross bracing together with improved suspension and steering rack. Externally the cars carried over the traditional TVR looks but they were markedly longer, especially at the front where space was made to mount the spare wheel above the radiator, which made serious improvements to the cars’ crashworthiness. Contemporary testers loved the new car with its sharp handling and progressive power. Motor Sport magazine compared the new 3000M with the TR6, Jensen-Healey and Datsun 240Z and concluded that the first two did ‘not deserve comparison with this delightful driver’s car’, while the Datsun lacked ‘the road manners and the V6’s splendid torque characteristics’.18

It went from strength to strength throughout the 1970s and had a number of new variants added to the line-up. First came the Martin, a limited-edition run of ten 3000Ms, each numbered sequentially and finished in gold and brown to commemorate ten years of ownership. More importantly, perhaps the biggest criticism that had been levelled at TVR since the Grantura was the difficulty of accessing any luggage in the rear of the car. This was improved in 1976 with the introduction of a modified 3000M, the Taimar, which had a hinged rear window that facilitated easy access to the rear compartment. The additional weight reduced the top speed from around 130mph (210km/h) to 119mph (191km/h) and marginally increased the 0–60mph time, but the car proved popular, in spite of its reduced performance, comprehensively outselling the 3000M in 1977, 1978 and 1979. Many people thought that the name Taimar came from ‘TAIlgate MARtin’ but Martin has recently confirmed that this was not in fact the case; instead, it was named after a friend’s girlfriend.19

A line-up of M Series cars at the Golden Mania TVR fiftieth anniversary celebrations at Brands Hatch in 1997. CHRIS WRIGHT

A very rare TVR 3000M Martin. This is No.5 of just ten built and named after Martin Lilley to commemorate ten years of the Lilley family’s ownership of TVR. ANDY HILLS

The interior of the same Martin showing the upgraded dashboard. ANDY HILLS

Tony Connor’s 3000M at Goodwood. TONY CONNOR

3000M SPECIFICATIONS

Engine

Ford Essex

Capacity

2994cc

Power

138bhp

Torque

174lb ft

0–60mph

7.7sec

Top speed

121mph (195km/h)

Suspension

Double wishbone

Brakes

Discs front, drums rear

Wheels

14 × 16in alloys

Tyres

185 HR

Price

£7,244

The most popular model in 1978–79 was another new design, the convertible, which quickly became known as the 3000S. While the very first convertible was simply a 3000M with the roof cut off, the production car, TVR’s first true soft-top since the early 1950s (unless one counts the one-off Trident and Tina convertibles of 1976 and 1977) was in reality a very different beast with a lower windscreen, sculpted doors, sliding sidescreens, completely redesigned interior and an all-new rear end.

In spite of a major fire at the Bristol Avenue factory in January 1975, the Lilleys were responsible for a number of other innovations including the first ever use of the heated rear window filament as the radio aerial, something that is now taken for granted. Perhaps their greatest claim to fame would be the introduction of the UK’s first production turbocharged car, the 3000M Turbo. Actually available as an engine option on any of the 3-litre models, the turbo cars returned TVR closer to the supercar performance of the Griffith and Tuscan V8 with an extra 20mph (32km/h) and taking a full 2 seconds off the all-important 0–60mph time, reducing it to under 6 seconds.

This view of Tony Hodgson’s Taimar, following a full interior refurbishment, clearly shows the access to the rear luggage area – so much easier than the original 3000M. TONY HODGSON

Peter Wheeler’s Nightfire Red Taimar Turbo. This car had a complete bodyoff, nut-and-bolt restoration in 2000 and an engine overhaul/refresh in 2009; it had covered fewer than 2,500 miles since then when this photo was taken. Other improvements include a Borg Warner T5 five-speed gearbox, Salisbury differential, stainless-steel exhaust and Wilwood four-pot brake calipers and discs. WIKTOR WILCZYNSKI

Roger Coulsey’s concourswinning Taimar Turbo arriving at Chatsworth House for the 2011 TVRCC gathering. TONY COTTRELL

It’s easy to see from the stunning lines on this 3000S why Martin Lilley observed that if he had had the resources to fully develop this car, it would have outsold everything. ANDY HILLS

Another view of PRW’s Taimar Turbo showing the opening tailgate, a first for a TVR. This was the seventh Taimar Turbo built, the second in 1977 and the seventeenth turbo overall. It was purchased new by Peter Wheeler and registered on 1 August 1977 with all invoices made out to ETA Ltd. WIKTOR WILCZYNSKI

When Jensen Special Projects developed the convertible for TVR they lowered the windscreen and dashboard, which is why the major instruments had to be moved to a central position. ANDY HILLS

The 3000S proved extremely popular. As Martin recalled, ‘If the convertible had been sorted out, it would have outsold everything.’20 At the time TVR simply lacked the resources to invest in its development, and that was one of the reasons why the initial development of the car was put out to Jensen Special Projects – and why it had such a low screen, which came from a Jensen Healey.

As the 1970s came to an end, TVR seemed to be on a high. They had a range of popular cars that could trace back their heritage certainly twenty years to the inception of the Grantura. They had a full order book and were in the black, making a small annual profit. This was all about to change.

Martin Lilley, seen at the 2006 TVR Car Club Pre-80s Gathering at Crich Tramway. He is in the driver’s seat of the factory press 4.3-litre Griffith with current owner Paul Bennett. ANDREA BENNETT

CHAPTER TWO

A NEW HAND AT THE HELM

While the M Series had been a great success for TVR, by the end of the 1970s the model was starting to look a little dated and distinctly 1960s, especially when compared with competitors such as Lotus. After all, the basic style had changed little since the 1959 Mk I Grantura. More to the point, as the then owner Martin Lilley was keen to point out, the M Series was based on components that, as the 1980s dawned, were simply not going to be available. With the 1600M and 2500M dropped from the range in 1977, TVR was wholly reliant upon the Essex 3-litre engine but this was about to be phased out by Ford, in Europe at least, and replaced by the fuel-injected Cologne. Electrics and running gear, which historically had come from the British Leyland parts bin, were similarly becoming increasingly difficult to obtain as their donor cars, such as the Triumph TR6, had long since ceased production.

There was also a desire to make production more efficient. So although it would easily have been possible to re-engineer the M Series to take a new engine, improved electrics and so on, and even design a new rolling chassis, all at TVR felt that the time was ripe for a fundamental change. Martin’s original concept for this replacement model, conceived with Mike Bigland, was to have a common central tubular section with a variety of front and rear options, enabling customers to have choice over model design while simplifying construction for a wide range of models. However, this idea did not come to fruition. Enter stage left, in 1977, Mr Oliver Winterbottom.

The Tasmin

An early Tasmin fixed head coupé (FHC). ANDY HILLS

Oliver was a renowned car designer who had previously worked for Jaguar and then Colin Chapman at Lotus where he had risen to become head of design, responsible for the Elite and Eclat and initial design work on the V8 engine destined for the Esprit. By the late 1970s he had taken a break from Lotus and was working as a freelance designer. He had penned a proposal for a new sports car, which Colin Chapman had allegedly turned down, and was introduced to Martin through a mutual friend, Mick Rawlings, whom Martin knew from his days at BarMoCo. This meeting breathed new life into Oliver’s project even though it was a radical departure from almost anything that TVR had built previously. Although there was some similarity with the 1960s’ Trident and Zante, but no direct lineage, its real styling origins lay not in Blackpool but Hethel, where it shared the angular definition of its Lotus cousins.

Another view of the same car. Note that this car has the full leather interior upgrade and a wooden ‘personal’ steering wheel; ex-works, it would have been fitted with a deep dish springlex wheel. Note also the early dish alloys. This style did not last long. ANDY HILLS

Martin was quickly sold on the proposal, which he originally saw in drawing form only, the quarter-scale styling buck coming much later, even after the first full-size bodies had been produced, recalled Martin.21 He decided to commission Oliver’s design, calling it the Tasmin. It has often been reported that the car was named after Martin’s girlfriend of the time, but that is not in fact the case. Martin was looking for a name that logically followed on from Taimar and he came across it when searching through a dictionary of names.22 He admitted that when he initially saw the first full-size car, he was somewhat disappointed as it did not look like the drawings Oliver had presented, which he recalled as being slightly softer, more rounded and more in keeping with the traditional TVR look, but by that stage it was too late.23 Too much money had been invested and there was no turning back.

The Tasmin was not going to be cheap. There were almost no parts in common with the M Series and it was going to take a radical shift for the factory staff and a huge capital investment to make this work. But Martin was convinced that he was on to a winner, as did his bankers who put up a significant proportion of the £250,000 investment. As Robson records, ‘He wanted to fight for markets which were progressively being abandoned by Triumph and MG.’24

In addition to Triumph and MG’s demise, a massive hole was opening up in the sports car market in the late 1970s. Manufacturers were shying away from convertibles for fear of litigation. The last E-Type had been produced in 1975 to be replaced in September of that year by the XJ-S, with Jaguar dropping the E-Type’s sports car credentials in favour of a relaxed, softer, grand tourer design. The convertible XJ-S did not appear until 1988. Lotus were producing some fine sports cars in the late 1970s, as were some of the new crop of Japanese manufacturers such as Datsun with the 240Z, and even the mainstream manufacturers had tried to fill the gap with, for example, the Ford Capri and Opel Manta, but TVR were largely filling a niche hole in the sub-Porsche/Ferrari market. The new styling, dragging the M Series into the 1980s, ought to prove a great success.

THE SPEEDLINE LOGO

JOHN BAILLIE

TVR’s famous Speedline logo, designed by John Baillie, first appeared on the Tasmin. John recalls the story.

I was involved with Oliver and Martin when TVR had their Research and Development set-up at Walton Summit. It was at this time that I took the TVR logo and refreshed it. In my view it was, and still is, a really classic car brand/logo. I believe the original was introduced around 1964, possibly created by Trevor Fiore, but Paddy Gaston comes to mind too. Rather like the GKN logo it was and still is, one of very few logos that ‘reads’ (T…V…R) but also forms a most satisfactory graphic shape.

The early Speedline logo seen here as a decal on the broad expanse of a very wet 350i nose cone. AUTHOR

The later 3D version produced as a chromed badge. The main difference is that the early design has no outline. This on a Griffith 500. TIM WOODCOCK

While working with the prototype Tasmin I felt that the traditional enamel bonnet badge would look rather lost on the expanse of relatively flat surface between the pop-up headlights, and so I took the opportunity to take the original logo and ‘stripe’ it. This was then produced in vinyl and applied flat to the surface at a larger but proportionally acceptable size. Being striped in a contrasting colour and allowing body colour to show through these elements rendered it a graphic form as well as making it clear that this was indeed a TVR! The factory designers ultimately developed this logo further through the 1990s and indeed it continues on the TVR Car Club logo and hopefully the future generation of TVRs! But it was me who first striped it, and I’m quite proud of that!

Chassis Development

First the Tasmin needed a new chassis. A 4in (10cm) longer wheelbase and a 3in (7.5cm) wider track meant that the Tasmin would be a markedly bigger car than its predecessor. This should not only provide improved comfort in the cabin area (larger drivers and passengers had struggled to squeeze into or out of the M Series cockpit) but also – more importantly – significantly improve the car’s handling and stability at high speeds.

Mike Bigland had left TVR and so, in keeping with the Lotus connection, Martin brought in ex-Lotus engineer Iain Jones to design the new chassis. Perhaps unusually, he dropped the M Series rear wishbones and introduced a trailing arm rear suspension, which was to prove to be the Tasmin’s weak point, especially as the engine power was increased. However, as Martin pointed out, the trailing arm rear suspension had been highly successful in the Lotus chassis that Jones had previously designed, so it was logical that he would use this design in the Tasmin.25 Furthermore, although the trailing arm might now be seen as a retrograde step from the M Series wishbones, at the time it was considered to be more than adequate – and in fairness, if TVR had stuck with just the 160bhp Cologne engine it probably would have remained that way.

The dreaded trailing arm rear suspension seen here on an early 350 chassis. TVR AUTOMOTIVE LTD