18,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: ibidem

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

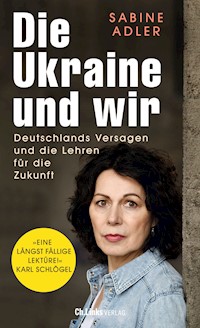

The war in Ukraine is putting Germanyʹs political and economic actions to the test. For decades, Ukraine, the second-largest state in Europe, was overlooked and Russia was courted. With fatal consequences. Germany has failed, as Sabine Adler states, an expert on Eastern Europe. Her analysis focuses not only on Ukraine and the current war, but above all on Germanyʼs role—in economic, political, and media terms—in relation to the country invaded by Russia. As a long-standing and clear-sighted observer, she gives a critical assessment: Political omissions, lobbyism, double standards, and a mendacious pacifism were dominant for long periods. Time for the West to learn from the bad example of Germany and to follow a sensible policy! Rarely do many years of local knowledge and familiarity with the history of the setting come together to such an extent as in Sabine Adler's Ukraine book. This is a long-overdue read!" —Prof Dr Karl Schlögel, University of Konstanz and European University Viadrina, Frankfurt/Oder. Dramatically enlightening book." —Christian Thomas, Frankfurter Rundschau (2023-01-14) An authoritative contribution." —Natascha Freundel, RBB Kulturradio (2023-01-10) Adler judges wisely and razor-sharp." —Viola Schenz, Süddeutsche Zeitung (2022-10-04) Sabine Adler's judgment is unflinching and free of doubt." —Peter Köpf, Karenina (2022-09-26) Adler manages with her book to hold a mirror up to us. She points out the errors in thinking." —Paul Toetzke, Liberal Modern(2022-09-07) This book explains a lot. You will be wiser afterwards." —Jörg Thadeusz, WDR 2 (2022-08-29) This might be unique at the moment, this form of depth of insight." —Bernd Schekauski, MDR Kultur (2022-08-18)

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 336

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Ähnliche

ibidem Press, Stuttgart

Table of Contents

Foreword

Introduction to the English edition

The tragedy

Chechnya as a blueprint for Ukraine

Putin, Schröder, Warnig—pretty clever friends

Merkel’s no to Kyiv’s NATO membership

Ukraine—a jewel in Putin’s tsarist crown

The Crimean “referendum”—a vote under Russian occupation

Sanctions as threatening as cotton balls

Fascists, patriots, and pacifists

Bahr, Eppler, Schmidt, and Schröder—the quartet of vain old men

German business in the interests of the Kremlin

Russia Day and climate foundation

Dangerous amateur historian—Putin declares the unity of Russians and Ukrainians

Blank spaces—Stalin’s terror and the unknown holocaust

One-sided consideration due to selective memory

More than just art theft—the Nazi foray through Ukraine

Merkel’s cold farewell, Chancellor Scholz’s tough start, and a scuttled joker

The Zeitenwende (turn of the times) speech

And in the future?

Sources

Acknowledgements

Foreword

by Andreas Umland

When the German version of this book, under the original title “Ukraine and Us” (i.e. the Germans), was published in autumn 2022 by Ch. Links Press in Berlin, this was an event by itself in Germany. Sabine Adler’s critical review of Berlin’s Ukraine policy represented then and still represents today a landmark in German political publicism. These are some reviews of the book’s German edition in a number of influential German media:

“A dramatically revealing book”—Christian Thomas for Frankfurter Rundschau;

“An authoritative contribution to enlighten [the readership about German-Ukrainian relations]”—Natascha Freundel for RBB Kulturradio;

“Adler evaluates [Germany’s relationship to Ukraine] with wisdom and the sharpness of a razor”—Viola Schenz for Süddeutsche Zeitung;

“Adler manages with her book to hold a mirror up to us. She points out the errors in [our] thinking.”—Paul Toetzke for Liberale Moderne;

“This book explains a lot. You will be wiser afterwards.”—Jörg Thadeusz for WDR 2;

“This [book] might be unique at the [current] moment, with its degree of depth and sharpness.”—Bernd Schekauski for MDR Kultur.1

Adler’s study was in 2022 and remains in 2023 one of the most consequential contributions to the currently ongoing German rethinking of the so-called Ostpolitik (literally: Eastern Policy) after the end of the Cold War. The German attitude towards Eastern Europe, in turn, has been one of the most significant international relations in Europe as a whole–in the past and until today. It will co-determine much of Europe’s future. It thus made sense to provide a wider public outside Germany with an English translation of Adler’s seminal study.

Like myself, Adler is an East and not West German with considerable life experience in the former Soviet bloc (we both studied, in different periods, at the Journalism Section of the then Karl Marx University of Leipzig). With her background in the GDR, Adler brings to the table a somewhat, in comparison to West Germans, different background and viewpoint on Russia, Ukraine, and Germany’s role in Eastern Europe. In her particularly long and strong skepticism towards Putin, as well as her explicit sympathy for Ukraine and other former Soviet republics, Adler joins a number of further influential German analysts of Eastern Europe with a biography in East Germany.2 They include, among several others, the late Werner Schulz who was a long-term member of both the German and European parliaments for the German Green party, Stefan Meister of the German Council on Foreign Relations (DGAP), Jörg Forbrig of the German Marshall Fund (GMFUS), and Andre Härtel of the German Institute for International and Security Affairs (SWP). Like these analysts, Adler has, for more than two decades now, been among those German experts on Eastern Europe who have, with their written publications and oral interventions, prepared the recent radical turn in Berlin’s attitude to Russia and Ukraine.

Readers should keep in mind that Adler’s book was originally written not for a foreign, but for a German-reading audience. It addressed especially readers among the political and intellectual elites of the Federal Republic, and, in particular, those living or working in Berlin. It is also not the only such recent German book which critically reviews German policies towards Russia and East Central Europe. Several important new studies by various journalists have come out after the start of the famous Zeitenwende (change of times) in February 2022. Among the most important and deep additional such studies are, in chronological order of their appearance:

Thomas Urban, Verstellter Blick: Die deutsche Ostpolitik [Biased View: The German Eastern Policy]. Berlin: Tapeta, 2022;

Michael Thumann, Revanche: Wie Putin das bedrohlichste Regime der Welt geschaffen hat [Revanche: How Putin Created the Most Dangerous Regime of the World]. München: C.H. Beck, 2023;

Reinhard Bingener and Markus Wehner, Die Moskau-Connection: Das Schröder-Netzwerk und Deutschlands Weg in die Abhängigkeit [The Moscow Connection: The Schroeder Network and Germany’s Path to Dependence]. München: C.H. Beck, 2023;

Winfried Schneider-Deters, Russlands Ukrainekrieg und die Bundesrepublik: Deutsche Debatten um Frieden, Faschismus und Kriegsverbrechen, 2022-2023 [Russia’s Ukraine War and the Federal Republic: German Debates on Peace, Fascism and War Crimes, 2022-23]. Stuttgart: ibidem-Verlag, 2023 (forthcoming).

Yet, Adler’s study represents, as of June 2023 when this foreword was written, still the only such German book specifically focusing on Ukrainian-German relations within Ostpolitik. Moreover, she has written not an academic study, but a book for a broader audience. Her investigation should thus be of interest also to a non-German and wider readership interested in the evolution of Berlin’s position vis-à-vis Kyiv and Moscow. It constitutes a vivid illustration, documentation, and interpretation of recent German debates, concepts and policies regarding the Ukrainian state, security in Eastern Europe, and the Russian threat. Whoever wants to understand the past, current, and future German relationship with Ukraine needs to read Adler’s book.

Stockholm, 11 June 2023

1 Source: “Die Ukraine und wir: Deutschlands Versagen und die Lehren für die Zukunft Gebundene Ausgabe–16. August 2022 von Sabine Adler,” Amazon.de, https://www.amazon.de/Die-Ukraine-wir-Deutschlands-Versagen/dp/3962891803/.

2 See, for instance: Jörg Thadeusz, “Sabine Adler - Journalistin und Expertin für Osteuropa,” WDR 2, 30 Jamuary 2023. https://www1.wdr.de/mediathek/audio/wdr2/joerg-thadeusz/audio-sabine-adler---journalistin-und-expertin-fuer-osteuropa-100.html.

Introduction to the English edition

When Europeans woke up on February 24, 2022, a war raged in Europe. Many think the first war since 1945, having forgotten the Balkan wars of the early 1990s and the war in eastern Ukraine that has been going on since 2014. Now Putin’s troops are attacking Ukraine from many directions; towns everywhere are being shelled with rockets, and tanks are moving in. A full-scale invasion is underway. Western military experts have long observed that more and more Russian troops are stationed on the Ukraine border. The US had warned the public in detail months in advance. The German government, the European Union, and the United States did their best to dissuade Vladimir Putin from his increasingly aggressive course toward Ukraine and NATO. But in response to Ukraine’s immediate need and request for help, Germany was late and persistently hesitant.

How could this escalation have happened? What have we overlooked? What mistakes were made in Germany and the European Union? These questions have been hotly debated in public since the beginning of the war and are the focus of this book. To answer them, looking only at the current situation is not enough. For that, it is also necessary to look back into history. Not only to 2014, when Putin occupied Crimea and fueled the war in eastern Ukraine, not only to 2013, when Ukraine refused to sign the EU Association Agreement, or till 2008 when Ukraine and Georgia were denied accession to NATO. And even beyond 2005, the year in which Chancellor Gerhard Schröder launched the first Nord Stream project with Vladimir Putin. It is necessary to look back even further: to the Chechen wars, to the collapse of the Soviet Union, of which not only Russia remained, but 14 successor states of the USSR, and of course, to the Second World War, from which Germany’s responsibility for Ukraine arises in a very special way. It has not been fully recognized until today.

I have observed the developments of the past 25 years as a correspondent from Russia, Ukraine, and Berlin. This regular change of perspective between Germany and Eastern Europe has shaped my perception of our relationship with troubled Ukraine. This book will also discuss this issue.

Berlin, May 2023

The tragedy

... begins with a joke that makes you laugh your head off. The world will witness a gigantic Russian troop deployment along the Ukrainian border for almost a year. In January 2022, there will be at least 130,000 soldiers armed to the teeth. In the face of this threat, the Ukrainians’ request for German weapons is becoming louder and more urgent. On January 19, the government in Kyiv asks again and becomes precise: Can Germany help with helmets and protective vests? Later, Ukrainian Ambassador to Berlin Andrij Melnyk added warships and air defense systems. The capital turns a deaf ear.

They have neglected Ukraine since 2014. Only a few, very few, are hearing the cries for help. Robert Habeck is open about it. In May 2021—before the German election campaign—he was on the front lines in eastern Ukraine. Habeck is one of the two Green Party leaders. There, he not only has a close look at the war that has not wanted to end for seven years but also listens to the hardships of the Ukrainian population on the demarcation line to the separatist areas. While still on the trip, he makes a strong case for the people asking for support to defend themselves against the pro-Russian occupiers. “Weapons for defense, for self-defense, I think it’s hard to deny Ukraine,” he told Deutschlandfunk Radio. “Ukraine feels left alone in terms of security policy, and it is left alone.”

In Germany, he is received with shame and disgrace. The CDU-led federal government at the time pointed to the principle of not supplying weapons to crisis regions. This is a political line also taken by Habeck’s co-chair of the Green Party, Annalena Baerbock. Unlike former party leader Jürgen Trittin, Baerbock does not distance herself from Habeck openly, but she does so audibly enough: “That’s also in our program, and that’s how we both see it as party leaders.” Habeck relents for the sake of Baerbock, the candidate for chancellor.

Unlike the Greens, the then SPD parliamentary group vicechairman Sören Bartol is not plagued by doubts. Unlike Habeck, he has never visited Ukraine, nor have most members of the Bundestag, not before or after the annexation of Crimea, not during the fighting in the east, not since Russia’s invasion. With Habeck, he said, you can see where such a trip leads: “Habeck visits Ukraine and already he’s denouncing the consensus. That’s naive.” Germany would be well advised to rely on diplomacy.

Berlin’s former mayor, Michael Müller of the SPD, also warns against traveling to Ukraine in the Berliner Zeitung onApril 21, 2022. Not because there is a war there and it is too dangerous, but because Anton Hofreiter (Bündnis 90/Die Grünen), Marie-Agnes Strack-Zimmermann (FDP), and Michael Roth (SPD) have come back full of emotion and with demands on the federal government, which is really not helpful. Strack-Zimmermann, who is considered to be a far more capable defense minister than Müller’s party friend Christine Lambrecht, then spoke plainly in the Tagesspiegel: “I would be happy to offer the new security expert Michael Müller to develop emotions in order to understand that a brutal war of aggression by Russia against Ukraine is not something that can leave us cold.”

The Left Party Member of Parliament Sevim Dagdelen outrages Habeck’s empathy with the Ukrainians, who for seven years have been trying, if not to oust the occupants in the east of their country, at least to prevent them from advancing further. “Anyone blinded by hatred of Russia who ignores the ultra-right militias in Ukraine and claims that the country is defending Europe’s security and therefore needs to be armed is a real danger to security in Germany and Europe.” For Die Linke, the real security threat comes not from Russia but from Habeck, Strack-Zimmermann, Roth, and Hofreiter, and those who want to help Ukraine defend itself against the aggressor. Dagdelen is not the only one who would like to see the Ukrainians sacrifice themselves to Putin, hoping his appetite would be satisfied. They sell this as a peace solution, pointing to Germany’s historical responsibility. Daria Kaleniuk cannot hear it anymore. The young Ukrainian, who heads the Kyiv Anti-Corruption Action Center, gets upset that Germany is holding back on military cooperation because of its role as a perpetrator in World War II, saying it is “one of the stupidest statements ever made.” On Twitter, she asks as early as January 2022, “Germany’s history has already killed millions of Ukrainians once, and now more should die because of Germany’s history?”

Meanwhile, Kyiv’s list of required weapons, helmets, and protective vests is on display at the Foreign Office, but the ministry remains silent. Finally, the defense minister sets a “very clear signal.” Christine Lambrecht announced on January 26 that Ukraine will receive 5000 helmets. President Zelenskyy cannot believe his ears and struggles to keep his composure. Vitali Klitschko rumbles: “An absolute joke! The mayor of the Ukrainian capital voices what is thought not only in Kyiv: ‘What does Germany want to send next for support? Pillows?’ “

While Germany continues discussing weapons assistance, more armed Russian soldiers appear on the Ukrainian border. Meanwhile, the country is threatened from three sides. From the east, where Russian troops have never really withdrawn after maneuvers despite repeated announcements. From the south, where the Crimean peninsula has been upgraded to a military base since the Russian annexation in 2014. And even in the north, there is Russian military in a foreign country, Belarus. There, the election fraudster Alexander Lukashenko is only holding on to power with the help of Vladimir Putin, to whom he has, in return, laid his country at his feet as a deployment area. The 200 kilometers to Kyiv are a stone’s throw. The engines are already running, initially for a Belarusian-Russian maneuver. In parallel, the Winter Olympics will begin in Beijing on February 4. Putin promises Xi Jingping not to overshadow them with war. At the 2014 Sochi Games, too, he sent his “green men “—special forces of the Russian armed forces in uniforms without insignia—to Crimea only one day after the closing ceremony. The countdown is on.

Poland, Latvia, Lithuania, and Estonia have long supplied weapons to the threatened country. Tallinn may have started supplying them in December 2021. The Baltic states wanted to give Ukraine nine howitzers. But because they came from stocks of the National People’s Army of the German Democratic Republic, the Estonians first had to ask Berlin for permission because German arms legislation requires a declaration of end-use. Anyone who buys weapons in Germany and then passes them on must state to whom and wait for approval. Berlin’s officials are taking their time. In mid-February 2022, when the three Baltic heads of government visited the new chancellor Olaf Scholz in Berlin, the Estonian colleague Kaja Kallas still received no answer as to whether she could use the old GDR weapons.

The German government has not decided whether or not it will be allowed to send these simply constructed guns to Kyiv. The Federal Republic of Germany sold 218 of them to Finland in 1992, and 42 howitzers were taken over by the Estonians in 2009, who now want to pass on exactly nine of them as quickly as possible. The new German government is putting on the brakes and acting like the old one in the coronavirus crisis: primarily bureaucratic. There is no trace of leadership.

Germany becomes an international laughing stock, first the helmets, then the howitzers. The Ukrainian house threatens to go up in flames, but Germany hands out the water bottle instead of calling the fire department. The traffic light coalition makes itself known to the world with a disastrous false start, to which Annalena Baerbock initially also contributes. On February 7, the foreign minister once again declared during her visit to Kyiv that there would be no arms deliveries from Germany. In doing so, she once again distanced herself from Robert Habeck. The Russian side would interpret Berlin’s massive armament of Ukraine as a provocation and make war more likely. Military aid could also damage Germany’s role as a mediator. However, this is impossible now because its reputation has already been permanently tattered on the world stage. Germany’s loss of authority means far more than just an image problem. The appearance as an international mediator, which Berlin would like to have, not least because of its supposedly good relations with Moscow, ended before it had even begun. Later—the war in Ukraine has already lasted almost two months—things worsen.

Frank-Walter Steinmeier is disinvited when he spontaneously wants to join a trip by his Polish counterpart Andrzej Duda from Warsaw to the Ukrainian capital in mid-April. The German head of state is an unwelcome guest in Kyiv now.

A scandal, an affront.

After Russia’s invasion, the German president sided with Ukraine and later admitted that he had made mistakes in his policy toward Russia. He seems to be getting away with it among Germans. However, German presidents have had to vacate Bellevue Palace for more trivial reasons. The Ukrainians do not make it so easy for Steinmeier. For them, he is the face of the German appeasement policy with Moscow par excellence. Moreover, no politician has so permanently and unswervingly championed energy dependence on Russia against all warnings. Steinmeier is now down for the count.

Meanwhile, Volodymyr Zelenskyy is waiting for Chancellor Olaf Scholz. Out of sheer consideration for those in his party who understand Russia, the so-called Russia-understanders, however, the Social Democrat wastes valuable time that Ukraine does not have. Scholz will first try his hand at crisis diplomacy and travel to Moscow to Putin’s white table in mid-February. Across the six-meter-long marble slab, he can only communicate with the Russian president via a headset. Since the coronavirus pandemic, Vladimir Putin has been extremely reluctant to go among people; when he does, he keeps an exaggerated distance.

For this reason, the Russian youth calls him “grandpa in the bunker.” Neither French President Emmanuel Macron, who was in the Kremlin before Scholz, nor Israeli Prime Minister Naftali Bennet, who will come after him, can get through to Putin. The German cannot because he does not mouth three words in Moscow: Nord Stream 2. A timely stop to the second gas pipeline from Russia to Germany might have made the ruler in the Kremlin sit up and take notice. But it did not come. Not after the annexation of Crimea, not at the beginning of the war in eastern Ukraine, not after the shooting down of passenger plane MH 17, not after the Novichok poisoning of Alexei Navalny. No offense, no matter how egregious, was significant to German Chancellor Angela Merkel. She had reason enough to pull the ripcord, and her successor has stuck to this course so far.

Putin’s antennas, therefore, remain switched to transmit instead of receive. He follows only one agenda, namely his own. He shares with his rapidly changing interlocutors his insights from a multitude of history books about tsarist Russia and the communist Soviet Union, which he read during the coronavirus lockdown. He not only mourns both empires, which no longer exist in either extension, but he has also wanted to restore Russia according to their models for quite some time. This is impossible without Ukraine. The neighboring country became Putin’s obsession, especially when he lost his most important man in Kyiv in 2013: Viktor Yanukovych, the president loyal to Moscow.

For years, Germany overlooked Ukraine, despite being the second-largest country in Europe. Only when the war approaches the EU border, when millions of Ukrainian women and children flee to Poland, Germany, and other EU countries while their men defend their homeland, is Ukraine finally noticed. Unlike politicians, citizens in Germany immediately understand that they must help. They become active with an enormous willingness to help. Many pick up war refugees directly at the Ukrainian-Polish border, take them in their cars to shelters or help at train stations to support the arrivals in finding their way. People are donating more money than ever before. Rarely have the electorate and politicians reacted so differently to a new challenge. Some do what they can, and others can do more.

Chechnya as a blueprint for Ukraine

If there were a world championship of Putinunderstanders, the winners would often come from Germany. Sometimes the race might be closer because Victor Orbán from Hungary, Aleksandar Vucic from Serbia, or Recep Tayyip Erdoğan from Turkey have caught up. But in 2001 and several times after that, the winner would have been Gerhard Schröder at the top of the podium. Schröder was and is unchallenged because no other foreign head of government can call Vladimir Putin his friend. However, such a friendship has to be worked for.

In 2001, Schröder did not simply invite the Russian president to Berlin as he had done the year before; this time, the guest from Moscow was to speak in the Bundestag. When Putin stepped up to the podium on September 25, he was 48 years old and had spent the longest period of his life in the KGB. He looks different from today, much slimmer, almost lanky. Two weeks before his trip to Berlin, Islamist terrorists attacked the US, sending passenger planes into the two towers of New York’s World Trade Center and the Pentagon in Washington and probably crashing a fourth over Pennsylvania. Putin was the first foreign head of state to telephone his US counterpart George Bush and offer him cooperation in the fight against terrorism. It was an impressive gesture not lost on Russian-American relations, which appear to be turning a corner. Putin is now on the front line with the US, alongside President Bush, to fight together against terrorism. A front that, according to his account, has long since run through the North Caucasus, through Chechnya, where Russia is waging war against Islamists with all its might. After the declaration of solidarity with the United States, criticism from Western capitals of Russia’s numerous human rights violations in this struggle fell silent.

The Russian begins his speech in the Bundestag in his mother tongue but immediately switches to German. Now everyone can hear how well he speaks the language of the country where he has lived for years. He speaks of the end of the Cold War, for which he receives a standing ovation. Only CDU chair Angela Merkel murmurs to her seatmate in the Bundestag: “We have the Stasi to thank for the fact that he knows German.”

While Berlin politicians enthusiastically applaud Putin, his troops are fighting against the population in Chechnya. The speaker mentioned the war: It was the answer to the attempt to establish a caliphate in the Caucasus. But the methods to stop the Islamists have been extremely questionable for two years. Moscow’s soldiers commit crimes against the civilian population. Men with their hands tied with barbed wire are found in Chechen mass graves, as in Bucha near Kyiv in 2022. In 1999, a maternity clinic in Grozny is shelled, killing 27 mothers and newborns, and a similar attack is repeated in Mariupol in 2022. Anyone still in the Chechen capital in October 1999 is considered a terrorist. Twenty years later, Ukrainians are called neo-Nazis or fascists by Putin. To sell the Chechen war in 2001 as a fight against international terrorism is Putin’s very own truth. He manages to make the crimes against the civilian population disappear from the politics of the day.

Chechnya could be a blueprint for Ukraine: first, a region is reduced to rubble, then the civilian population is further decimated and massively intimidated by massacres, and finally, it is forced under Moscow’s thumb by force. After the small Caucasus Republic, Putin has now set himself a much more ambitious goal with Ukraine, but the man in the Kremlin has long since lost touch with reality. He will not voluntarily return to the negotiating table, but only if defeat threatens and his calculations do not add up.

For German Chancellor Gerhard Schröder, who criticized Russia for the violence in Chechnya in 1999, it ceased to be an issue in 2001. Six months before September 11, he initiated the Petersburg Dialogue with Vladimir Putin. The two are close, have the same macho posturing, and have a similar background from a low-income family. The supposedly civil society forum is linked to the German-Russian government consultations. The organizers see the presence of the chancellor and the Russian president as a maximum dialogue enhancement. But the media interferes with this right from the start. At the founding event in April 2001 at the University of St. Petersburg, Peter Boenisch, ex-government spokesman for Helmut Kohl and now chairman of the steering committee, was telling German journalists that they were not needed here. Reporting with their negative headlines about the war in the Caucasus would only spoil the mood. A declaration of war from the highest—German!—place. From now on, reporters and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) that receive a similarly brusque reception are considered troublemakers.

The business representatives regard the Petersburg Dialogue more as a club of dignitaries than a platform for civil society exchange, which is how the committee should be sold to the public. Those who do not allow their interest in Russia to be paid for with sponsorship money, who are interested in an open exchange of opinions, have not understood the actual purpose in the eyes of these people and are out of place here. Since the German economy partly finances the association, it belongs to it. This is, to put it casually, the motto. A business card as a member of the Petersburg Dialogue opens many doors for Moscow companies. And, of course, no one wants to be seen forgetting about democracy and freedom when contacts can be made. Human rights activists and the media are in the way. They are treated with corresponding hostility. The Russian side makes it even easier by inviting almost no Kremlin critics at first and, later, none at all.

At that time, Vladimir Putin had been president of the Russian Federation for just under a year. Before that, he had been prime minister for a few months; a post President Boris Yeltsin offered him in August 1999 because no one else wanted to lead the ailing Russian state. Yeltsin went on to fight the first Chechen war from 1994 to 1996. The second war in the Caucasus Republic is added to Putin’s new post gratis. Despite his past as head of the Security Council and director of the domestic intelligence service FSB, he is completely unknown in his own country. Russia is in a ruble crisis; the oil price is so low that extracting it is proving more expensive than selling the fuel. There is still no peace in the Caucasus, despite the first war. Quite the contrary. There is fighting again. This time, foreign Islamists want to establish an Islamic state with Chechens and Dagestanis. All the politicians had only waved them off when Yeltsin offered them the post. Putin jumped at the chance. He is the right man for the outgoing president because he is prepared, without much ado, to grant Yeltsin lifelong immunity from prosecution.

“Who is Mr. Putin?” everyone asks in 1999. But soon, the answer is known. In early September, apartment buildings explode in Moscow, Buinaksk, and Volgodonsk. These are attacks in which more than 300 people die, and the Russian security authorities attribute them to Chechen terrorists. An accusation that is never proven in court. Rumors persist that Russian intelligence blew up the houses to provide a new pretext for another Chechen war. Duma deputies and journalists pursuing this lead are killed. The ex-agent Putin puts himself in the spotlight. Russians are supposed to understand that he is the antithesis of the incumbent head of state with his heart and alcohol problems. To demonstrate strength and determination, Putin issues a threat in a televised address to the nation on September 23, 1999: “We will follow the terrorists everywhere. Whether we get hold of them in airports or—excuse me—in toilets. Then that’s where we’ll kill them!” Many viewers will never forget the ice-cold look on the prime minister’s face, distorted with rage, and will recognize it in the later hate speeches against Ukraine.

The Ukrainians are currently experiencing the same mercilessness of Putin as the Chechens before them, who are also citizens of his own country. The czars had already cut their teeth on Chechnya. The ex-KGB spy used force to bring the small rebellious people in the Caucasus to their knees. It was only after ten years that the “Anti-terrorist operation” ended. Alexander Dvornikov leads it. Putin later relied on this general in Syria and Ukraine, who was known for his brutality. Much is repeated in terms of warfare. The Chechen capital Grozny is completely bombed, as is Aleppo in Syria in 2015 and Mariupol in 2022, where Chechen special forces are deployed.

They are “Kadyrovtsy,” troops of Ramzan Kadyrov, to whom Putin has entrusted control of the punished rebel republic. Kadyrov enjoys a fool’s license in the Kremlin; he is Putin’s man for the rough stuff. He has journalists and politicians shot, such as Anna Politkovskaya in 2006, Natalya Estemirova in 2009, and Boris Nemtsov in 2015. Renegade Chechens are executed in Austria and also in Germany. Zelimkhan Khangoshvili is shot dead in the so-called Tiergarten murder in Berlin in 2019. Investigations at home and abroad lead directly or indirectly to Chechnya and thus to the head of the Russian constituent republic, as in the case of the murder of the Russian opposition politician Boris Nemtsov, the two female journalists and other colleagues of the independent newspaper Novaya Gazeta, or the victim in Berlin’s Tiergarten.

However, the president is also guilty of several other law violations. But no matter what Kadyrov is guilty of, Russia’s criminal authorities, who take the toughest possible action against the free press or the opposition, look the other way in the governor’s case, born in 1976 in Zentoroi, Chechnya. Corruption, rightly deplored in Ukraine, is blooming wildly in Chechnya. A palace on a plot the size of two soccer fields in the center of Grozny, costing more than four million Euros, belongs to Fatima Khasuyeva. The 30-year-old owns other apartments in other cities. Her official salary in the presidential administration, where she works, is less than 900 euros. How the office worker owns a palace, Maria Sholobova has found out. She is a journalist in the Russian investigative research group “Project” and uncovered a major real estate and corruption scandal involving Kadyrov in 2021, with the result that her Internet portal was closed and she had to flee abroad.

Maria Sholobova’s research team did what would have been the duty of the tax authorities and the Land Registry office: to determine whether everything was correct with this palace. The journalist made inquiries and found out: Kadyrov has a second wife, Fatima Khasuyeva, in addition to his first, and lives with her quite openly. Russian laws also apply to the constituent republic of Chechnya; polygamy is forbidden. Ramzan Kadyrov does not care. Rather, he lectures on how several wives must be treated simultaneously: equally well dressed, with equally valuable houses, and given furs, and cars. The devout Muslim Kadyrov has introduced a strict traditional regime in Chechnya; the laws of blood feud apply, and women have to wear headscarves. Medni Kadyrova, whom he first married, obeys him. According to Kadyrova, her religion allows her husband to marry three more women. If that is what he wants, she agrees. Medni Kadyrova also owns several valuable properties. Since the marriages with the second, third, or fourth wives are only concluded in front of the imam, but not in the registry office, everything is supposedly legally in order. Almost, because with the help of the two wives, whether in registered marriage or not, Kadyrov is allegedly concealing part of his wealth. Real estate alone amounts to 800 million rubles, or just under nine million Euros. The head of the 1.5-million-strong republic earned around four million Euros in 2020. The year before, he earned only 1.6 million Euros, and in 2018, as little as 80,000 Euros.

The citizens do not find out how these large fluctuations occur. According to him, the car fanatic does not own a vehicle as he often presents himself. Not a single car in his impressive fleet, including sports cars from the most expensive brands such as Bugatti, Ferrari, and Mercedes-Benz since the beginning of his political career, is his own. The Russian news portal lenta.ru added up the horsepower gathered there and came up with over 3800 hp, although allegedly only the luxury models were counted for this. Similarly, the more than 100 horses of his racing team do not appear in the official data of his ownership. They win almost a million Euros in prize money from 2014 to 2018 in the United Arab Emirates and Russia. The secretary general of Transparency Russia, Ilya Shumanov, was careful to point out in this context that it is possible to earn money in horse racing, but it must be controlled.

Ramzan Kadyrov becomes prime minister at 29, then president of Chechnya at 30. He succeeds his father, Akhmed, in office. Akhmed is killed in an assassination attempt. The son feels himself to be the unrestricted ruler of his empire and beyond. He likes to brag about his possessions, which should be of interest to tax inspectors, and at the same time, raise questions about their finances. Kremlin spokesman Dmitry Peskov summarily dismisses the discrepancy between Kadyrov’s income and his wealth, as the report by the research group “Project” proves: “Research is one thing, declarations are another. All the heads of the regions fill out declarations, which are then checked. The data checked by state anti-corruption units are much more reliable than that of the media.”

Independent journalists like Maria Sholobova of “Project” live dangerously in Russia, so many work from abroad. The award-winning author took a big risk with her research on Kadyrov. Russian authorities are often not interested in those who violate the law but in those who expose it. This has never been as obvious as in the case of the anti-corruption activist Alexei Navalny. For Kadyrov, such publications have so far remained inconsequential. He is untouchable. If secret torture prisons and extrajudicial killings do not resonate with law enforcement agencies, his illegal enrichment certainly does not.

The Chechen government orchestrates mass arrests, abductions, and mistreatment of people because of their sexual orientation. Veronika Lapina of the LGBT network has tried to initiate investigations. “But Russia either doesn’t have the capacity or the will to deal with it,” she states. Since 2017, 235 persons have been arbitrarily arrested, imprisoned, and tortured by Chechen security forces, or at least that is how many have contacted the St. Petersburg-based network. Most affected are homosexual or bisexual men whose way of life does not fit with Ramzan Kadyrov’s understanding of gender. Russian law enforcement agencies do not deal with these crimes. The reason for this is an agreement, the human rights lawyer from St. Petersburg is convinced: Kadyrov ensures that terrorist and separatist activities are stifled, and in return, he receives full freedom of action in Chechnya. President Putin spreads his hands protectively over Ramzan Kadyrov.

Russia could wage war in eastern Ukraine, Syria, Georgia, or Chechnya—for the Germans, everything was far away, too special, and not important enough for a continuous and intensive occupation. Those who pointed out the crimes and demanded consequences were only annoying. Russia was just different, too big, and incapable of democracy, were the explanations of those who understood Russia, who did not notice how much arrogance was in their words. But above all, it is about business.

Not supplying Ukraine with weapons would not mean ending the deaths faster, as some pacifists are convinced, but it would mean that Putin can establish another terror regime—on Ukrainian territory.

Putin, Schröder, Warnig—pretty clever friends

Despite the start of the second Chechen war in 1999, German Chancellor Gerhard Schröder does not keep his distance from the Kremlin but gets closer and closer to it. Ten days before the 2005 federal election, whose outcome is expected to be close, Schröder and his now longtime friend Vladimir Putin strike a deal. They wrap up a deal in case the Social Democrats lose the election. On September 8, in Schröder’s and Putin’s presence, representatives of Russia’s Gazprom, BASF’s German subsidiary Wintershall and E.ON sign a contract to lay a gas pipeline on the seabed of the Baltic Sea from Vyborg to Lubmin. The German-Russian agreement seals the creation of the operating company Nord Stream. Matthias Warnig becomes managing director. The idea for such a 1224-kilometer pipeline originated in 1997 from the Russian gas producer Gazprom and the Finnish oil and gas company Neste. Now Putin wants to turn it into reality.

On December 9, 2005, the former chancellor receives a call on his cell phone from the Kremlin. At a late hour, Putin offers him the Nord Stream shareholders’ committee chairmanship. Schröder finds this premature, less than three weeks after leaving politics. But since he has never kept a secret that he mainly wants to earn money in his new life, Schröder agrees. Criticism is not long in coming because it is one thing to stand up for his country’s energy security as a politician but quite another to profit personally from an investment project worth billions that he has just pushed as chancellor. But nothing blows Schröder away that quickly. He has always been proud of his friendship with the Russian president, whose closest allies for the new pipeline are now two Germans. For Putin, the SchröderWarnig duo represents the ideal appointment. The Social Democrat has had an ardent career as prime minister of Lower Saxony and chancellor of Germany and has left politics at just the right time for Putin’s taste. And he has the necessary temerity. A few days before his resignation, the outgoing chancellor secured a loan guarantee of over one billion Euros from the German government for Nord Stream. This was completely overlooked in Berlin’s political scene amid coalition talks. The bombshell only explodes six months later when the finance ministry informs the Bundestag’s economic committee in writing. The SPD comrades, who had entered into a grand coalition with the two CDU/CSU parties, were mortified by the billion-euro guarantee. But the former chancellor is long gone by then. Frank-Walter Steinmeier has to prove himself for the first time as Schröder’s most important man in the new federal government and sweep up the pieces as quietly as possible. But after twelve years at Schröder’s side, the chief diplomat has had practice at this.

The ex-chancellor needs a new sense of achievement. The consulting contract for the Swiss publishing house Ringier, which he signed just a few days after leaving office as head of government, is a nice start, but he needs more. At 61, he is still bursting with energy and has excellent contacts with the EU heads of state and government. He wants to keep them on the ball. When he calls, he does not have to introduce himself. Ideal conditions for Nord Stream. Above all, the countries bordering the Baltic Sea are needed now because they are supposed to approve the gas pipes on their section of the seabed. Since Poland, Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia are likely to give up on a project initiated by Russia, the route for the pipeline has been defined differently. Finland, Sweden, and Denmark have to be asked. Fortunately, their heads of government come from the international social democratic party family. For Schröder, this is a manageable task.