9,59 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Forum

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

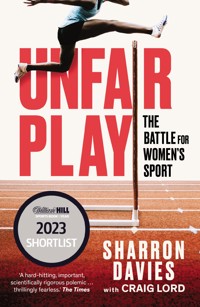

A TIMES AND DAILY TELEGRAPH BOOK OF THE YEAR SHORTLISTED FOR THE SPORTS BOOK AWARDS 2024 Sharron Davies is no stranger to battling the routine sexism of the sporting world. She missed out on Olympic Gold because of doping among East German athletes in the 1980s; now, biological males are being allowed to compete directly against women under the guise of trans 'self-ID'. This callous indifference towards women in sport, argue Sharron and journalist Craig Lord, is merely the latest stage in a decades-long history of sexism on the part of sport's higher-ups.Unfair Play provides the facts, science and arguments that will help women in sport get the justice they deserve. 'A compelling account of how women in sport continue to be subjugated' Daily Mail

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 520

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Ähnliche

This book is dedicated to my family, who’ve had to put up with my crusade for justice these last few years. It’s also for all the wonderful men and women who have taken on the abuse and fought alongside me for fair play, safety and the right for female athletes to have equal opportunities in sport. Sport is something I am forever grateful for. It has shaped my life.

Contents

List of Illustrations Introduction 1 This Is a Man’s World 2 Let the Doping Games Begin 3 How We Were Cheated 4 Moscow and the Manipulators 5 Sex Matters 6 Sporting Differences 7 Gonads and Gotchas 8 The Game Changer 9 The Swimmer Who Proved the Science 10 The Onslaught against Women 11 The Gender Industry 12 Why Girls’ Sport Matters 13 Green Shoots – and Swimming Turns the Tide 14 Truth and Reconciliation 15 The Fight Goes OnAcknowledgements Appendix 1: The Key Studies and Papers on Retained Male Advantage after Transition and the Meaning of Fair Play Appendix 2: Resources Appendix 3: Fair Play for Women’s Guide to UK Equality Law and a Woman’s Right to Single-Sex Spaces and Services Appendix 4: Letter from Fair Play for Women to the IOC Executive Board Appendix 5: The State of Inclusion Policies – Global Federations, March 2023 NotesList of Illustrations

1 The gender gap in Olympic sport 2 How long women had to wait to join men in Olympic sports 3 Androgenic-anabolic steroids 4 Mind the gap: GDR women’s and men’s swimming medals, Olympic Games 1976–80–88, individual events 5 Stasi document showing the positive tests 6 Petra Schneider and doping boss Manfred Ewald on the cover of GDR Schwimm Sport magazine, 1980 7 The reality of male advantage in sport 8 Katie Ledecky versus the boys: where the all-time great woman ranks among the best boys and men 9 Missy Franklin and Ryan Lochte 10 Shaunae Miller-Uibo and Wayde van Niekerk 11 GBR Olympic champions swim relay, Tokyo 12 The power of T: how 15-year-old boys beat the best Olympic womenIntroduction

There’s a moment before an Olympic final when time stands still and the champion mindset fills the void – or not. Mental toughness plays a big part. Races can be won and lost in that gap between the whistle that calls an athlete to their blocks and the firing of the starting gun.

Friends, family, coaches, even a nation, are confident on your behalf, while you, the athlete, have self-belief built on long, hard years of work and the knowledge that you left no legal stone unturned in your preparation. At that moment your enemies are not your opponents but fear of failure, fear of blame, fear of letting down the people who’ve made big sacrifices for you along the way.

Knowing that the next few minutes of a race are likely to define you for the rest of your life is scary!

In fact, when I get nervous today I always look back to that moment and think, ‘If I could manage that I can pretty much manage anything.’ Sport has been a blessing in my life – it’s made me strong, even if the strain has worn out a few bits of my body.

From a young age, my dad and coach Terry taught me to be tough, to be ready for any challenge. There were years of intense, all-consuming work before my first Olympics at 13, then four more years under huge scrutiny and expectation until I lined up in Moscow aged 17 at the Games again. This time, it meant the biggest moment of an Olympian’s life: the battle for an Olympic title.

I was in the form of my life for the 400 metres medley final in the swimming pool, but I also knew that it wouldn’t be enough to win. I might even miss out on a medal altogether because the lanes next to me included three East German women on male steroids and programmed to be decades ahead of their rivals.

‘Take your mark…’ Bang! For the next 4 minutes, 46 seconds, all thought and energy is ploughed into being the very best you can be when it most counts. The clock stops. It’s silver ahead of two East Germans and I’ve set a British record that won’t be broken for more than two decades. The 1980 Games end with me as the only female individual medallist on the whole GB Olympic Team. That’s how hard it is to beat an unfair advantage.

Enhanced by testosterone, the winner of my race sets a standard good enough to make most Olympic podiums and every Olympic final for the next 41 years.

We all knew why. I’d trained every day for years knowing I was facing that unfair advantage, knowing that I was being cheated out of medals at every passing international competition. It was the same for my teammates and women from countries all over the world. And not a single person in authority raised a red flag or fought at the top tables of Olympic power for us, for a level playing field, for the pledges set out in the Olympic Charter.1

Had it not been for the German Democratic Republic (GDR) fraud, I would have had Olympic and European titles as well as World Championship medals to go with my Commonwealth golds. My British teammate Ann Osgerby would also have been an Olympic gold medallist. She would have led a totally different life because of the opportunities that would have come her way. And Ann was far from being the only one. So many women lost their rightful rewards because of the GDR and because the International Olympic Committee (IOC) failed to stop the cheating and turned a blind eye to the truth.

We’ll show you just how bad it was later in the book.

Everyone in sport knew it. Most had to look no further than the shape and musculature of the East German girls. It turned out that not a single GDR medal-winning performance among women was achieved without drugs. We didn’t know precisely what those drugs were at the time, nor how they were getting away with it. When the cast-iron proof of mass systematic cheating came flooding in with the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, Olympic sports authorities let it go.

To this day, I feel a deep sense of despair that we don’t learn from history. Having failed female athletes for half a century by refusing to take action when a whole nation doped its females with a decisive dose of male advantage, Olympic authorities have watched the transgender crisis unfold and responded in exactly the same way. They’ve let it go.

Yet again, it’s female athletes who will pay the price. They are the only ones who will lose rewards, recognition, status, opportunities and lifelong benefits.

This time it’s not artificial testosterone in doses just big enough to guarantee gold. It’s the full force of male biological development that’s been given a ticket to female competition, making contenders out of mediocre males self-identifying their way out of biological reality to a new status in sport.

Having lived a lifetime of injustice, I was determined not to let it happen again. After five years of campaigning for the women’s category to be ring-fenced for females, I watched unfair play reach my own sport of swimming in predictable fashion.

I was transported back four decades by the cries for help from the women who faced Lia Thomas, a 6' 4" biological male, at the American National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) championships in 2022. Not only did they have to compete against an opponent fresh out of three seasons of racing as a man at the University of Pennsylvania, but they were also threatened with exclusion and expulsion if they complained that they’d been forced to change alongside an athlete with male genitalia intact and exposed.

It was a case of sports authorities being so influenced by the politics of societal trends that they failed female athletes in monstrous style.

We’ve been forced to confront increased physical danger in contact sports and rising mental-health challenges because inclusion has meant invasion, injustice and ultimately exclusion from our own category. There’s a denial of peer-reviewed science and wilful blindness to the loss of opportunities for women to make teams, finals and podiums or to write their achievements in CVs and on job applications. The consequences of being cheated out of such things span whole lifetimes, as we know from the fallout from the GDR years.

The threat to female sport, to women’s rights, including safety on the field of play and privacy in the locker room, reaches every level, grass roots upwards. Even on primary school sports days, mixed-sex races are being encouraged, leaving young girls with nowhere to shine. What message does that send?

Females have been told that we must pretend that male development has nothing to do with meteoric rises up the rankings by biological males who on transition go from average men to champions among women. Yet again, everyone on the side of the pool or track knows the truth. Few of them have been asked by their governing bodies to speak it.

For saying such things, I’ve been vilified, accused of being transphobic, a bigot, even sexist (not sure how that works) and a right-wing extremist. It’s got nothing to do with politics. I have always fought for everyone’s right to human equality and safety to be themselves. Radical activists don’t want to hear anything that they can’t turn into a weapon in their cancel-culture campaigns that result in loss of livelihood and death threats – something that my family and I have faced. We’re not alone.

It’s a successful tactic. The insults are meant to shut you up and the lies are used to ruin reputations, inflict financial harm and drain people of their will to fight back. It’s bullying, plain and simple, and we shouldn’t tolerate it as some suggest we should purely on the grounds that trans people are ‘an oppressed minority’. Whether they are or not, this member of a much larger, but still oppressed majority feels it’s only fair to mention that the United Nations Human Rights Council (UNHRC) and related UN 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development note that women’s rights, including those on equality and access to food and education, are among the most violated on a consistent basis.2

In his book Half the Sky, Nicholas D. Kristof notes that, in the last 50 years, more girls were killed precisely because they were girls than men were killed in all the wars of the twentieth century.3

Numerous UN reports, including depressing projections for poverty suggesting a worsening crisis, show how a range of key problems around the world have a disproportionate impact on females, at national and international level.4 Pay gaps across the developed world including in the UK are still a big issue.

I was one of those preparing for a forum in Cardiff in 2022, at which women just wanted to meet and discuss their concerns, when we had to inform police that trans activists were threatening to burn down the venue with all of us in it. We ought to have been shocked, but it’s par for the course in the vile debate over trans rights and how they impact others.

Activists turn up to women’s forums in balaclavas, hurling obscenities. Some get arrested for their attacks, yet many politicians are loath to openly defend women’s rights the way they should, and the way the vast majority of the general public want them to, as polls often show us. Why is society so scared of this extremely vocal minority?

We delve into that question in the pages of this book, which include the science that explains why sport must be safe, then fair, then inclusive, in that order, not inclusive at the expense of all else.

The exclusive nature of sport is the very thing that makes it inclusive to a wide range of people across society. Where the 15-year-old is excluded from the under-tens, the younger children enjoy fair play. Where able-bodied athletes are excluded from the Paralympics and Paralympians are divided into categories, there is fair play. Where heavyweights are excluded from lightweight bouts, lightweight fighters get to enjoy sport in a safe and fair environment.

Where males are allowed into female sport, safety and fair play are crushed.

It’s all such a very long way from the sport my co-author Craig and I grew up in, with our fathers as coaches. One of the myths trans activists have on repeat is that sport is based on gender not sex.

From school galas to national and international events, all the way up to the Olympic Games, for the entirety of sporting history (until very recently) sex and gender have meant the same thing: biological sex. Girls and boys or women and men. Those categories were not created to accommodate a feeling. They were created to facilitate equality.

Entry forms, starts lists and result sheets all have men’s events and women’s events. There has never been any other description, nor has anyone in sport I know ever assumed that the definitions of women and men have meant anything other than biological sex. The crusade to undermine this makes a mockery of sport’s classifications. The option is always there to create more if need be, not ruin the present ones, but even getting respectful debate has been hard.

I realised six years ago that women’s sport was about to face the same kind of systematic injustices female athletes faced during the 1970s and 1980s, during the East German doping era. My conscience would not allow me to sit back, carry on getting well-paid jobs and ignore what was unfolding. I felt compelled to spread awareness and help to stop the nightmare happening all over again.

In 2018, when tennis ace Martina Navratilova heard that trans activist Rachel McKinnon/Veronica Ivy, a biological male cyclist, had become a World Masters title winner in the women’s 35–44 category, she called it insane and tweeted: ‘You can’t just proclaim yourself a female and be able to compete against women. There must be some standards, and having a penis and competing as a woman would not fit that standard.’5

It amounted to cheating, said Martina. In my opinion she was spot on. It’s cheating given a green light by sports bosses breaking their own rules on safety and discrimination. But it’s cheating all the same.

Martina was accused by McKinnon/Ivy of having an ‘irrational fear’ of something that doesn’t happen. McKinnon/Ivy said: ‘There’s a stereotype that men are always stronger than women, so people think there is an unfair advantage.’6

Men being stronger than women is not a stereotype. It’s a biological reality reflected in every Olympic result throughout history. In these pages, McKinnon/Ivy’s ridiculous statement will be reduced to rubble, along with the other false gotchas of activists blind to the facts presented by well-qualified, world-class sports scientists and experts.

As Professor Margaret Heffernan notes in her insightful book Willful Blindness: ‘We may think being blind makes us safer, when in fact it leaves us crippled, vulnerable, and powerless. But when we confront facts and fears, we achieve real power and unleash our capacity for change.’7

Women have been battling for change in sport since it all began. We’ve only been able to run in the marathon at the Olympics since 1984, and even though swimming got going for females in 1912, we were outnumbered by men four to one when I raced at the 1980 Games. We’ve fought tooth and nail to get to a better place and look what’s happening now.

So let’s talk human biology, peer-reviewed studies and decades of Olympic results. Let’s banish the blind eye and welcome the truth.

My book is a personal quest to expose that truth and put pressure on those in authority to do the right thing, not the easy thing.

1

This Is a Man’s World

Let’s start where it all began. The inclusion debate needs to be understood within the wider context of sexism and misogyny in female sport throughout history. Women’s claims are ignored because sport is a man’s world – and few things illustrate this better than the history of the Olympic Games.

The Olympics: an ignoble history

The IOC strongly encourages, by appropriate means, the promotion of women in sport at all levels and in all structures… with a view to the strict application of the principle of equality of men and women.

– rule 2, paragraph 5 of the Olympic Charter 1996

This statement sounds good, but ‘strongly encourages’ is typical of Olympic guidelines, which proclaim positive sentiments all too vaguely. Sports leaders will agree to such statements but soon abandon them if they prove to be inconvenient.

When it comes to critical issues like equality and doping, which have a direct impact on the welfare and lives of athletes, the Olympic creed has more holes in it than a Swiss cheese from a dairy not far from IOC headquarters in Lausanne.

Women first joined the Olympic Games as token participants in 1900. As Image 1 shows, it was 92 years before female athletes made up more than 25 per cent of all participants at the Games. In Moscow, where I won my medal in 1980, I was outnumbered four to one. In my lifetime, there have been 19 Olympics, including the 12 I raced or worked at, and men have had the lion’s share of opportunities and events to target.

1 The gender gap in Olympic sport. Source: International Olympic Committee

At the Covid-delayed Tokyo Olympics of 2021, women got closer than ever to making up half of all athletes: 48.8 per cent to 51.2 per cent.8 This included the first three biological males to identify as women and be allowed by the IOC to compete against female athletes.

The official records don’t show that those athletes were males in competition with females, just as the official books of results and records don’t show that all the East German girls were on drugs at the time they won their medals. Of course, we know categorically that they were, just as we know that transwomen are biologically male.

It’s against that backdrop that we’re supposed to believe that ‘promoting gender equality within the IOC has been an important objective of the organisation since the creation of the Women and Sport Working Group in 1995.’9 As we’ll see later, the 1990s were devastating for generations of sportswomen as a direct result of IOC decisions, while the IOC’s boast that in 1996 it ‘took the historic step of amending the Olympic Charter to include an explicit reference to the organisation’s role in advancing women in sport’ is highly questionable in the context of the inclusion model that has ripped equality out of the heart of female sport these past several years.10 Olympic leaders know the movement has a very poor record on equality.

The truth is that the men who have run the show for over a century are not the ones who have promoted women’s sport. Women’s sport grew thanks to female athletes and coaches, strong mothers, members of women’s rights groups and sports organisations, who had to fight long and hard every step, stride, stroke, pull, push and throw of the way to achieve equality.

Pierre de Coubertin is celebrated at every opening ceremony as the founding father of the modern Olympics. The truth is that he was the father of men’s sport at the Games and the patriarch who effectively told women to stay out.

They could partake in the festivities in 1896 as long as they had ‘chaperones’ in tow – but forget the sport. That was all about a display of athletic performance reflecting men’s abilities, endurance, strength, virility and courage. Women had none of that, according to Coubertin, and so their participation was pointless. He did have a job for them, though.

Coubertin, a French baron, said: ‘Women have but one task, that of the role of crowning the winner with garlands. In public competitions, women’s participation must be absolutely prohibited. It is indecent that spectators would be exposed to the risk of seeing the body of a woman being smashed before their eyes.’11 He was still trotting out sexist tropes in 1919, when women dared to suggest adding track and field and other events for women at the Olympics. Coubertin scoffed at the idea and suggested it was impractical, uninteresting, unaesthetic and, he even added, ‘improper’.12

Frenchwoman Alice Milliat was not prepared to give up in the face of these attitudes. Alice met the IOC and the International Amateur Athletic Federation (IAAF), then an organisation of men for men, in 1919. She brought a gift, a chance for the men to show their vision and allow female participation in the Olympics. They declined, and sent her back to sewing and scrubbing dishes.

So, after some hard graft, Alice founded the Fédération Sportive Féminine Internationale in October 1921.13 After organising the Women’s Olympic Games in Monte Carlo in the same year, in 1922 she set up the Women’s World Games, which were held every four years until 1934.14 Before he stepped down from the IOC presidency in 1925, the disgruntled Coubertin felt the way the wind was blowing and agreed to add fencing for women.

But men were the real show, women a token warm-up act and novelty. Concessions were made where Coubertin felt the activity was ‘ladylike’ enough. Golf and tennis could be played in a skirt down to the ankle, so that was allowed in 1900. Those were extremely elite sports for women to gain access to, but, by 1912, women’s swimming was in. Well, sort of – at least on the surface.

The blokes made the rules and they’d been swimming at the Olympic Games since 1896. When permission was given for women to swim at the 1912 Games, the IOC restricted the number of events to just two, the 100 metres freestyle and the 4×100 metres freestyle relay. The men had six individual events in freestyle, backstroke and breaststroke and a relay twice as long.

The first women’s Olympic swim champion was Australian Fanny Durack.15 When she and fellow national swimming champion Wilhelmina ‘Mina’ Wylie made it known that they wanted to race at the Olympics, the New South Wales Ladies Swimming Association (NSWLASA) delivered the bad news handed down to them by the men in charge of the Australian Olympic Committee (AOC): they’d only pay for the Australian men to go to the Games, including the 21-day voyage.

Women protested and the men agreed to a compromise loaded with a gotcha. Fanny and Mina could go to the Games if they paid for themselves and the chaperones they were required to have with them. The AOC and the NSWLASA misread public opinion: Durack’s exclusion was seen as a national scandal. Fundraisers were organised and the women reached their target.16 Those women were real heroines, in my opinion. Fanny won the 100 metres to become the first Olympic women’s swimming champion. Mina took silver and Britain’s Jennie Fletcher took bronze.

With only two women, Australia could not enter the relay. Jennie Fletcher was joined by teammates Isabella Moore, Annie Speirs and Irene Steer, and Britain took the first women’s swimming relay gold in history.17 Years later Jennie recalled: ‘We swam only after working hours and they were 12 hours a day, six days a week. We were told bathing suits were shocking and indecent and even when entering competition we were covered with a floor-length cloak until we entered the water.’18

It wasn’t only in swimming that women defied the sexism of male event organisers. At the 1896 Olympics, pioneering heroine Stamata Revithi used the men-only marathon to prepare her answer to the sexism in her own way. Not all the blokes finished their run, but she did the day after, covering the 40-kilometre marathon course in five hours.19

It wasn’t until Los Angeles in 1984 that women were allowed to run the marathon at the Olympics. That was 18 years after Bobbi Gibb became the first woman to run and complete the Boston Marathon.20 She didn’t do so officially, of course. The 23-year-old had to hide in a bush near the marathon start line and disguise herself in a hoodie after she was disqualified from entering the race because of her sex.

A year later, in 1967, Kathrine Switzer entered the Boston event as ‘K. V. Switzer’ and organisers just assumed that the name was that of a man. When the male runners spotted the woman running alongside them, Kathrine was attacked by race co-director Jock Semple, who ran her down and tried to rip the number off her sweater as he screamed, ‘Get the hell out of my race!’ Kathrine’s American-football-playing boyfriend body-slammed Jock onto the verge at the roadside. They all ran off and Kathrine became the first woman to officially complete the race. Imagine having to have your own bodyguard just so you can run!21 Jock later made his peace with women running in the marathon.

Kathrine remembered that the all-male press were ‘crabby’ and ‘aggressive’ and made her feel ‘so afraid’ when they asked: ‘What are you trying to prove? Are you a suffragette or are you a crusader?’ When one said to her, ‘You’re never going to run again,’ Kathrine replied: ‘We’ll be back and we’ll be back again and again, and if our club is banned, we’ll form a new club… someday you’re going to read about a little old lady who’s 80 years old, who dies in Central Park on the run. It’s going to be me. I’m going to run for the rest of my life!’ Kathrine is still going strong and is one of a vast club of female athletes who showed the way, fought their corner, refused to accept discrimination.22

Charlotte Epstein was another pathfinder. A courtroom stenographer, she founded the Women’s Swimming Association in New York City in 1917 and became famous for promoting the health benefits of swimming as exercise. She staged suffrage swimming races and campaigned for women’s rights and changes to swimsuits to allow women freedom of movement. The swimmers she coached set 51 pioneering world records.23

In 1923, swimming regulator the International Swimming Federation (known as FINA, the initials of its French name, the Fédération Internationale de Natation) set up a committee to consider what they called the international swimming costume for women. Charlotte got wind of it and insisted they hear from the women who’d have to wear them. It took a while, but FINA consulted her at the 1924 Olympic Games and it was agreed that the suits would have to be black or dark blue, would be cut no lower than 8 centimetres below the armpit and no lower than 8 centimetres below the neckline, and would have material that descended into the leg by at least 10 centimetres for the preservation of modesty, including a slip back and front of at least 8 centimetres.24

Epstein served as a manager of the US women’s Olympic swimming teams in 1924 and 1928. As a Jew she boycotted the 1936 Olympics in Nazi Germany, where Coubertin was brought out of retirement to help promote the Berlin Games and sit alongside Hitler in a Swastika-filled stadium.

Coubertin and the Nazi Party were close bedfellows when it came to the role of women. In a 1933 speech, Joseph Goebbels, chief Nazi propagandist, said: ‘We do not see the woman as inferior, but as having a different mission, a different value, than that of the man. Therefore we believe the German woman… should use her strength and abilities in other areas than the man.’25

In return for Coubertin’s patriarchal promotion of what are sometimes called the ‘Propaganda Games’, the Nazis nominated him for the Nobel Peace Prize in 1935.26 And the winner was… anti-Nazi campaigner Carl von Ossietzky.27 IOC leaders still aspire to the Peace Prize. They’ll probably never get it because there’s something they just don’t understand and possibly never will. Cosying up to Putin, Xi Jinping, the leading family in North Korea and a flotilla of sheikhs and emirs hosting and funding the Olympic Movement isn’t an act of peace, nor one of understanding. For the Nobel Peace Prize, you actually have to do something noble, peaceful and courageous, like stand up to bullies and dictators and call out their corruption and human-rights abuses (in theory at least).28

Or, perhaps, stand up to the endemic misogyny and bullying of men in the way that Stamata, Alice and Charlotte, among many others, did. They endured the mockery of men and pressed for inclusion in the face of fierce resistance from the likes of Coubertin. Nowadays, he is celebrated as a great founding father by a generation of men who are forcing women to accept male advantage in female sport in the name of inclusion. How apt.

Letter to M. Macron

At the 139th IOC session, during the controversial Beijing Winter Olympics in 2022, Guy Drut, the 1976 French Olympic hurdles champion and now IOC member, proposed that Coubertin’s remains be reinterred at the Panthéon in time for the Paris 2024 Olympics.29 Drut wrote to French president Emmanuel Macron to propose his plan. The current IOC president, Thomas Bach, thought it a wonderful proposal but he doubted the IOC could help. Bach wished Drut the best of success with his initiative.

Men are still celebrating men a hundred years on. So, early in 2023, I wrote to President Macron, too, as well as the head of the French sports ministry until 2022 Roxana Maracineanu, an Olympian and a world swimming champion for France in 1998. I asked them to use Paris 2024 as an opportunity to celebrate the women who made it all happen for female athletes, not the misogynist who blocked them. Of course, we should not erase Coubertin from history and it’s hardly surprising that the IOC and France would wish to commemorate his founding-father status at an Olympiad held in Paris. At the same time, in 2024 we should also expect, at the very least, Coubertin’s regressive and sexist views to be recognised by the IOC and organisers.

Let’s celebrate the women like Alice Milliat who fought for equal rights, Monsieur Macron, not the misogynist who never included women in that famous French ‘liberté, égalité, fraternité’ of yours.30

The truth is that the spirit of that grand French national motto has only ever truly applied to men in sport.

When Qatar was making headlines over its human-rights record and not its hosting of the FIFA World Cup in 2022, Macron said that politics should be kept out of sport. By just saying that as the president of France he was of course bringing politics into sport. Perhaps diplomacy with the IOC is what he had in mind.

What he didn’t mention was the scandal of France’s involvement in the 2022 World Cup host bids. Perhaps the meeting before the FIFA vote that year between the French president Nicolas Sarkozy, Michel Platini and the emir of Qatar at the Élysée Palace was entirely innocent and had nothing to do with Sarkozy’s desire for Qatari investment in Paris Saint-Germain.31 What is certain is that Platini chose to vote for Qatar shortly after. Former FIFA president Sepp Blatter is on record as saying that Sarkozy had asked Platini to vote that way. Bidding has been inherently political for a long time.

We should be asking serious questions about whether countries with some of the world’s worst human-rights records, including with regards to women’s rights, should be hosting major sporting competitions. This is particularly the case when it comes to football.

It’s striking that 2022 World Cup host Qatar was close to the bottom of the World Economic Forum’s ‘Global Gender Gap Report’ that year.32 This tracks gaps between women and men in employment, education, health and politics. Rights groups say that the Qatari legal system and its male guardianship law hinder women’s advancement and are highly discriminatory.33 There is a discussion to be had about whether sport should get involved in any debate about the practicality or advisability of imposing Western moral values on Islamic countries.

That issue cropped up during the World Cup in 2022, but with narrow focus: there was constant coverage of protests in support of the LGBTQ+ community but we heard very little about the lack of equality for women, which affects a much larger number of people.34 It often appears that the rights of males, including gay men and transwomen, come right at the top of the political agenda in sport. Women are an afterthought or not even thought of at all.

Sports leaders who claim to be staunch supporters of gender equality and have been telling female athletes to be reasonable, stop complaining and be more welcoming to a new wave of biological males self-identifying as transwomen are the same men who voted to have Qatar, a country with no elite female athletes, host its showcase events.

It’s no use Macron or anyone else saying we should keep politics out of sport. Sport is up to its neck in politics, power, business and the money that it generates.

Think back to the pre-World Cup press conference in Qatar. FIFA boss Gianni Infantino tried to brush aside all the human-rights concerns about football’s controversial choice of Qatar as host when he said:

Today I feel Qatari. Today I feel Arabic. Today I feel African. Today I feel gay. Today I feel disabled. Today I feel like a migrant worker. Of course I am not Qatari, I am not an Arab, I am not African, I am not gay, I am not disabled. But I feel like it, because I know what it means to be discriminated against. To be bullied, as a foreigner in a foreign country. As a child I was bullied – because I had red hair and freckles.35

Spot the missing ‘I am’. Infantino didn’t mention feeling like a woman. At least not until a journalist pointed out he’d missed half the world, to which the Italian official answered: ‘I feel like a woman too!’36

He hasn’t a clue what it feels like to be a woman. This is all about the business of men.

Swimming to equality?

From the start of the modern Games, women have had to fight tooth and nail with every passing Olympics to get closer to true equality. It’s been a long haul. In 1900, there were just two women-only events. Men had 95. Parity has been hard fought for. Even where a sport includes both men and women, women have often been deemed incapable of covering the same distance, enduring the longer match, taking on the same number of events. We’re still not there when it comes to tennis or the decathlon.

Women started swimming at the Olympic Games in 1912, but it was 2021, in Tokyo, before the women swam the same events as the men. Some of the gender gaps in Image 2 are breathtaking.

Women swimmers did quite well. They only had to wait 16 years to compete at the Olympics. For athletes and gymnasts, it was 32 years, speed skating 36 years, equestrianism 52 years. Women couldn’t be trusted with a gun for 72 years; rowers waited 76 years, cyclists 88 years, women water polo players 100 years. But the prize for the record wait is wrestling, a sport that has been part of the Olympics from the beginning in 1896: 108 years.

2 How long women had to wait to join men in Olympic sports

The governance gender gap has been even worse. It’s hard to believe, but when I raced at my second Olympics in 1980 there had still not been a single woman member of the IOC. The first one was elected in 1981: one woman and 14 men. Today, there are more women but still five times more men than women at senior executive level and twice as many men in the boardroom overall.37

At executive level, there are five senior positions, only one of which is occupied by a woman, Nicole Hoevertsz, from the Dutch island of Aruba in the Caribbean, who finished eighteenth out of the 18 duet teams in synchronised swimming at the 1984 Olympic Games with teammate Esther Croes for the Netherlands Antilles.

In simple online searches for news and features from around the world, I cannot find any references to a single one of those women speaking in support of female athletes in the trans debate. Nor do I see any support for inquiry, truth and reconciliation over the East German doping decades.

In total, there are 102 full members of the IOC, 43 honorary members and one ‘honour member’ (Henry Kissinger). Of the 146 members in total, just 38 are women. The list includes two kings, six princes and three princesses. Of the 38 women, 16 are from countries where women are distinctly treated as second-class citizens and suffer life-shaping discrimination of the kind illegal in many parts of the world, including the UK, according to the country profiles of organisations such as Amnesty and Human Rights Watch.38

And we’re not even talking about the standard, ever-present struggle highlighted by the World Bank on International Women’s Day in 2022.39 It noted that about 2.4 billion women of working age are not afforded equal economic opportunity and that 178 countries maintain legal barriers that prevent women’s full economic participation. More than a dozen female IOC members hail from countries that human-rights groups cite as places of deep discrimination towards women. The human-rights violations perpetuated by these countries include beatings, stoning and differences in the age at which men and women can marry, with girls as young as 12 being forced into arranged marriages with men decades older than them.

There are more than 50 countries in the world, including IOC member nations, where rape within marriage is still legal. No surprise, then, to find that women are not encouraged or even allowed to participate in elite sport in many of those countries that are represented in decision-making roles at the IOC.

The governance structure and gender gap in my own sport, swimming, provides insight into many Olympic sports. In 2020, the ‘Third Review of International Federation Governance’, published by the Association of Summer Olympic International Federations (ASOIF), put FINA at the bottom of the league, along with weightlifting and judo, over matters of discrimination and transparency.40

A glance at the gender gap in swimming governance highlights one of the key findings of the governance survey. Founded in 1908, FINA was 113 years old before it included a single woman on its top team, now known as the executive. It took until 2000 to add a single woman to its board.

Reform is now reshaping the sport, and, in December 2022, FINA was renamed World Aquatics and a heartening decision was taken to set a minimum quota for women on the board (or bureau) that works out at just shy of 40 per cent.41

There’s more work to be done. By the end of 2022, there was a commitment to reduce some of the 400-plus voluntary governance roles on 27 committees at FINA, which are 80 per cent male and at least half of which are occupied by political appointees. On the cusp of reform, 11 of the 27 groups had no women representatives even though their work involves particular focus on issues that affect women.

Between 1998 and 2021, there has been a tenfold increase in delegates from the Middle East and countries that have very few male elite aquatic athletes and almost no female athletes of any standard. This means that men from countries where women’s rights are restricted have risen to key positions of authority in FINA.

It is true that there are women involved in sports governance, and there is no doubt that there are some good women in governance positions today. But when I look through the ranks of those who are there, I can’t help thinking that they represent what men in sports governance may well consider to be the right kind of women: those who will cause them no problems, will do good work to a certain level but will never raise a red flag on a whole range of big issues because to do so would probably mean that they would lose their positions.

Frankly, it’s been very disappointing to see how many strong women go into governance and then prove totally ineffective. I understand that these people have sometimes fought to get to those places. There must be something in them that motivated them in a good way. But it’s frustrating to see fine athletes who must have had a fighter instinct to win races as sportswomen just roll over and become part of the machine, keeping their heads down, staying on message, avoiding issues if they aren’t convenient to the leadership.

Those women who do get into positions of authority in FINA have faced a rampantly misogynistic culture. Craig once interviewed Julio Maglione, the Uruguayan president of FINA, in the lobby of a five-star hotel. Just as the interview was about to start, the FINA boss spotted an old friend and shouted out, ‘Eh! Hijo de puta!’ – meaning ‘son of a whore’ – as women and children wandered past. He engaged in a short but foul-mouthed exchange that the two individuals had dragged straight out of the locker rooms of their youth.

At the time, Maglione was staying in the suite, had a chauffeur and limousine at his beck and call, an ‘executive volunteer’ credit card and enormous, often pre-paid privileges that extended to first- and business-class travel, all meals, and a daily allowance of over $500 even though he had no expenses. They were all covered. It’s not my definition of a volunteer.

Where Maglione might have been considered one of the boys for his foul language, a woman would be deemed a disgrace if she spoke that way. Where a man might be called aggressive, a woman is a bitch or, that favourite, a ‘difficult woman’. If a girl is said to have slept around she’s a slut, whereas a man doing that is just a lad. We’re in the 2020s and that negative terminology used for women is part of the culture that keeps us in our places, and men in the driving seat.

Some of that old culture left with the departure of Cornel Mărculescu after 34 years as FINA director, and the reform process under way is already reaping fine dividends, as we’ll see in Chapter 14.

The old guard are well past their sell-by date. For far too many years, they’ve been telling sportswomen what to wear – and like it. We’ve had volleyball players being told they’re not showing enough bottom and that the shorts men wear just wouldn’t be aesthetic enough.42 There are countless other examples, many infuriating. I know young gymnasts who were asking to be able to do their routines in more comfortable, athletic kit, like shorts, not leotards, and being told they couldn’t. Then transgender competitors arrived on the scene and all of a sudden they were allowed to wear shorts.

An illusion of progress?

Sport is a tough place: females already have less prize money, less access, less media coverage and less profile in general. Now we’re also supposed to compete at a disadvantage, against known males who have gone through male puberty. The consequences include loss of places on teams, loss of chances to make finals, loss of chances to win medals and gain access to all the related opportunities that follow.

Despite this, the success of the Lionesses and Emma Raducanu, and the fact that the media like to boast of having a women’s sports correspondent on their team these days, has given the impression that we’re talking about a new golden era for women’s sport.

But just from my own experience I know that isn’t true. It actually means more coverage for women’s football, rugby and cricket or any Brit who wins a big pro title. But this isn’t the case in many other sports. When it comes to female swimming, the new coverage has displaced much of the old. In many sports, historically there was no need for a women’s correspondent: sport-specific specialist correspondents like Craig have been writing about women in sport for decades, and in my racing days we had three international matches a year, all televised. We had big companies like Esso and Green Shield sponsoring youth and senior swimming. Now, apart from track and field, Olympic sports are lucky if they make TV once a year, and often that’s on a red button.

If you take a straw poll on the high street, and ask people to name five female Olympians, they’d probably end up naming mainly retired ones, or a couple of track stars who appear on yoghurt adverts. They’d struggle to name the current top British female swimmers, even the ones who won relay gold medals in Tokyo. And that’s because we get less coverage between Olympics now than we did in my racing days.

The ‘Gender in Televised Sports’ report, issued by the Center for Feminist Research at the University of Southern California, was published in 2010 and covered the 20-year period from 1989 to 2009, citing a survey of early-evening and late-night TV sports news across a range of broadcast media. By 2009, men received 96.3 per cent of all airtime, women 1.6 per cent and neutral topics – whatever they are – 2.1 per cent. Another study ten years on found that the picture was practically unchanged and that 80 per cent of the televised sports news and highlights shows included zero stories on women’s sports. Not one. The findings were written up in a paper subtitled ‘The Long Eclipse of Women’s Televised Sports, 1989–2019’.43 The research is excellent, the findings truly depressing.

While women are no longer portrayed in demeaning ways as sexual objects or as the brunt of commentators’ sarcastic ‘humour’, editors pay less attention to women in general. It is not only women who are overlooked. Seventy-two per cent of airtime goes to men in just three sports: basketball, American football and baseball – all traditional magnets for advertising revenue and generators of the biggest audiences that accounted for the bulk of coverage even out of their season. The popularity of individual sports has to be taken into account, but there’s more than a little ‘chicken and egg’ about it: if people don’t ever get an opportunity to see certain sports and women in them, it’s obvious that there won’t be an audience to grow. The rise in popularity of women’s football has surely made that point.

That said, governing bodies could do so much more to grow the viewing figures for women’s events, like putting major games on after the men’s matches at venues such as Twickenham and allowing full stadiums to stay and watch. Invest to grow. Stadium numbers are increasing. Mainstream TV stations are airing big finals with big build-ups, especially in team sports. And the women are delivering. We can see the skill and fitness of the women’s game. Men are also chatting about the tactics and talent in women’s games. That’s a very recent trend. It’s heading very slowly in the right direction but men in boardrooms could still do so much more.

Olympic sports federations have a constitutional obligation to ‘grow’ and promote their sports, but the difference between the periods of popularity during a Games every four years and what happens in between is often stark. Why? Where are they going wrong and what might be done about it? In the digital age, when organisations seem to think they have it covered by appealing directly to ‘the fans’, where is the engagement with the mainstream media that provides a fundamental part of coverage in big pro sports? You can’t grow a sport if you only ever talk to those who already love you.

Tributes to Dickie Davies, the frontman on ITV’s World of Sport, who passed away in February 2023 aged 94, included a clip from his 1981 review of the year in which he tells viewers: ‘Whatever the sport we cover – and that’s right across the spectrum – there are those moments that occur that enliven, humanise and soften the serious business of competition. They so often spark off sporting chat in the pubs and living rooms and they provide us with warm and amusing memories.’44

‘Right across the spectrum’ is the key phrase. It’s not happening in the UK today because emphasis is so heavily on the top handful of sports that take up all the oxygen in the media room. Craig tells me that things are different in Germany, where TV sports shows and even news bulletins still cover a wide range of sports and celebrate any German athlete who excels in any sport, regardless of whether the audience is the size of football fandom or that of handball fandom. Success makes the news and feeds into follow-up profiles written by print media and television documentaries.

If those news stories and profiles get no airtime or column inches in print, then success is something we only celebrate for those engaged in the most popular of activities. If we set sport aside and turn briefly to music, we find that, in the United States in 2018, pop, hip-hop and rock accounted for 56 per cent of all album sales, while classical accounted for 1 per cent. Does that mean we can’t find public and commercial broadcasts and constant newspaper reviews of classical music? No.

Of course, unequal treatment by sex and sport is not confined to media coverage. Men’s teams travel with dieticians and personal chefs, while the women muck in at the hotel buffet or tournament canteen. In 2019, the Lionesses flew from London to Nice for the World Cup on a British Airways flight and then made headlines when they took an EasyJet flight to a friendly in Portugal months after the England men’s under-21 squad had flown to their European tournament on a private jet, the class of travel the England men’s team has become accustomed to.45 In 2020 the Lionesses flew to the United States for the SheBelieves Cup in premium economy and returned business class.46 While the return journey was a step up from the economy class that most Olympic athletes travel in, the Football Association’s decision on the women’s flights came less than two years before the England team lifted the European trophy and attracted the biggest TV viewing figures for a home tournament in history, highlighting the ugly gap between women and men in the Beautiful Game.47

Similar things happen far and wide. Sedona Prince, the Oregon Ducks basketball star, highlighted the same issue in the United States in a video revealing the difference between the NCAA women’s and men’s weight-training rooms.48 Women got the IKEA flat-pack version in a tiny room while the men got a state-of-the-art palace of pumping to work in.

However, we do need to retain a note of realism. We pay male footballers millions of pounds: their female equivalents get less in a year than a male Premiership footballer gets in a week. Some say that this situation should be equalised, but the hard truth is that the market for that is just not there. I do understand supply and demand. Sometimes women prefer to go shopping, or to watch Strictly, Coronation Street or The Kardashians rather than sport. Fact: there are a lot more male spectators on a Saturday afternoon than there are female spectators.

It also needs to be said that if women want to have equal prize money, then women need to run as far and play as many sets. We shouldn’t have a heptathlon on the track in the Olympics for women. We should have decathlons for men and women. If men can do ten events over two days, so can women. None of those events in the decathlon is anything that’s not done by women as an individual sport today. If it’s about the ultimate athlete, then the ultimate athlete does ten events, not seven. Let’s have real parity.

There are grounds for optimism. We all saw the outpouring of love for the Lionesses and that has to be a positive development. The problem is that the bosses still think of them as economy-class ticket holders and it’s yet to be seen how long the drive to promote the women’s game will last. I know they have had sessions in the UK Parliament to discuss how to harness all this enthusiasm. I hope it lasts longer than last time!

Whether it’s big professional or Olympic sport, there is often only a small window of opportunity for women to grab attention, while men’s sport gets huge coverage every single day.

2

Let the Doping Games Begin

Sporting crime of the century

Let’s face it, female athletes have been abused, denied, discriminated against, ignored, robbed, sacrificed and starved of justice by men manipulating women and breaking fair-play rules for as long as anyone can remember. To those of us still haunted by the ghosts of East German doping in the 1970s and 1980s, that era serves as a particularly cruel reminder of past wrongs.

Two groups of men bear responsibility for that dark chapter in Olympic sport.

First, we have the all-male leadership of the Communist GDR, hungry for success in sport to promote its political ideology at all costs. And then there are the Olympic bosses who not only failed to protect athletes through adequate policing of the scam unfolding on their watch but actually placed some of the leaders of the East German doping programme on the committees tasked with catching cheats and keeping sports clean. The aim of those GDR leaders was to guarantee that a nation of 17 million people punched well above its weight in sports based on speed, strength and endurance.

To do that, the leaders and those following their orders doped generations of athletes with anabolic steroids. Cheating with banned substances proved immensely successful for the politicians and perpetrators, but catastrophic for female athletes on both sides of the Cold War in sport.

What might be called the ‘sporting crime of the twentieth century’ was highly misogynistic. Success relied overwhelmingly on administering testosterone to teenage girls to give them some of the male advantages that naturally come from the steroid. As we’ll see in Chapter 5, the best boys can beat the best ever females in a range of sports by the age of 15.

I was just 11 when I raced at my first junior international for Great Britain, and 13 in 1976 at the first of my three Olympic Games. At the same tender age, some East German girls in sports such as swimming, rowing, track and field, cycling, weightlifting and gymnastics were on a schedule of testosterone pills and injections and on their way to becoming Olympic, world and European champions, some as young as 15.

GDR athletes were weaponised in the biggest clinical trial on athletes in history, females the key target. Estimates suggest that up to 15,000 athletes, known as ‘ambassadors in tracksuits’, had been doped between the late 1960s and the fall of the Berlin Wall on 9 November 1989.

The girls were very strong and very fast, and had male physical characteristics as they lined up against us. In some of the sports that relied heavily on explosive force and strength, like shot-put, javelin and hammer-throw, GDR women were the size and shape of men as a result of the huge doses of testosterone they were given.

Brigitte Berendonk, who competed in track and field for West Germany and later became an author and lifelong, award-winning campaigner for clean sport, and her husband Professor Werner Franke, an oncologist who was also honoured by the German state for his anti-doping work, were two of the leading voices for truth and justice on GDR doping. They helped save hundreds of official state-secret documents from the shredders as East German security police tried to get rid of the evidence the moment it became clear that the days of the GDR were over.

In a 1997 paper presented to the Doping in Sport Symposium in Leipzig, they summed up what they had unearthed in 1990, and what Berendonk had published in her book Doping: von der Forschung zum Betrug (Doping: from research to fraud)in 1992, as follows:

Several thousand athletes were treated with androgens every year, including minors of each sex. Special emphasis was placed on administering androgens to women and adolescent girls because this practice proved to be particularly effective for sports performance. Damaging side effects were recorded, some of which required surgical or medical intervention.49

Olympic shot-put champion Heidi Krieger was among those given doses of testosterone in her youth so extreme that medical intervention was required. By 18, Krieger had developed many masculine traits. East German records noted by Prof Werner Franke and Brigitte Berendonk show that she was administered with 2,600 milligrams of male steroids in 1986 alone. That’s nearly 1,000 milligrams more than Ben Johnson took when cheating ahead of being banned during the Seoul 1988 Olympics.

In 1997, at the age of 31, Krieger underwent sex-reassignment surgery and changed name to Andreas. A year later, Andreas would testify against the doctors and coaches, who were convicted of bodily harm. Krieger has since married former East German swimmer Ute Krause, who was also a victim of systematic doping in the GDR. Andreas told Heidi’s story and his story of transition in a moving documentary for the US Anti-Doping Agency (USADA) in 2015.50

The architects of cheating put national glory above human safety. Some of the banned substances used were even tested on teenagers who had been hand-picked at six years of age, measured for expected growth and development, allocated to a sport they and their parents were told they were suited to, and placed in special schools. It appeared to be an honour, but what no one told the families was that coaches and doctors awaited the youngsters with a toxic tonic of banned substances.

Among those given drugs were many who never made it to international competition. During the doping trials in 2000, some of the athletes described themselves as guinea pigs in the GDR experiment to find the champions whose names we got to know. I’d never heard of Jutta Gottschalk and Martina Gottschalt (we learned from the doping trials that the latter was an age-group backstroke champion at 13, around the time she was put on a doping regime), but their evidence in the trials was among the most moving. Jutta’s daughter was born blind while Martina’s son was born with a club foot. Der Spiegel reported from the trial that Dr Lothar Kipke, the senior swimming doctor in charge of doping, had told his bosses that in pregnancy embryos could be damaged by the anabolic steroids. He wrote: ‘During pregnancy, transplacental virilization of the female fetus.’51

In an interview with Die Zeit