Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Mercier Press

- Kategorie: Fachliteratur

- Sprache: Englisch

Tadhg Barry was the last high-profile victim of the crown forces during the Irish War of Independence. A veteran republican, trade unionist, journalist, poet, GAA official and alderman on Cork Corporation, he was shot dead in Ballykinlar internment camp on 15 November 1921. Barry's tragic death was a huge, but subsequently largely forgotten, event in Ireland. Dublin came to a standstill as a quarter of a million people lined the streets and the IRA had its last full mobilisation before the Treaty split. The funeral in Cork echoed those of Barry's comrades, the martyred lord mayors Tomás MacCurtain and Terence MacSwiney. The Anglo-Irish Treaty was signed three weeks later, all internees were released and the movement that elevated him to hero/martyr status was ripped asunder in the ensuing civil war. The name of Tadhg Barry became lost in the smoke. This is the first biography of a fascinating activist described by his British enemies as an 'Utter disloyalist' and by a comrade as 'a characteristic product of Rebel Cork – courageous, kindly, generous to a fault, bold and daring, and independent in speech and action'. It offers fascinating new perspectives on the dynamics of Ireland's long revolution, including glimpses of the roads not taken.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 409

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

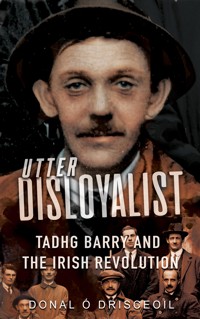

A memorial postcard issued following Tadhg Barry’s death in November 1921.

Courtesy of Cork Public Museum

Dedication

To the memory of another rebel and writer from Blarney Street, Mary E. Mulcahy

MERCIER PRESS

3B Oak House, Bessboro Rd

Blackrock, Cork, Ireland.

www.mercierpress.ie

www.twitter.com/MercierBooks

www.facebook.com/mercier.press

Cover Design: Sarah O’Flaherty

©Donal Ó Drisceoil, 2021

Epub ISBN:978 1 78117 800 3

A CIP record for this title is available from the British Library.

This eBook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

Printed and bound in the EU.

A handbill song-sheet featuring the ballad ‘For God and Ireland True (In Memory of Ald. Tadg Barry)’ (anon.).

Courtesy of Kilmainham Gaol Museum/OPW

Acknowledgements

Sincere thanks to Tadhg Galvin, grandnephew of Tadhg Barry, who has championed his memory for many years and has been an invaluable help. Thanks also to Barry’s grand-nieces and his other grand-nephews, especially Barry O’Shea. My gratitude to the McDonnells of Templeacre Avenue, past and present, who stimulated and sustained my interest in their relative. Special thanks to my colleague John Borgonovo, who has been unfailingly generous with sources and insights arising from his wide research on and deep knowledge of revolutionary Cork. My gratitude also to the late Peadar Murnane, Will Murphy, Niall Murray, Michael O’Keeffe, Andy Bielenberg, Michael Lenihan, John O’Donovan, Diarmuid O’Donovan, Richard McDonnell, Alan McCarthy, Sarah-Anne Buckley, Liam O’Callaghan, Diarmuid Ó Drisceoil, Ann Piggott, Trevor Quinn, Liam Ó Duibhir, and the late, great Ronnie Herlihy. Seán Ó Laoi very kindly translated a document handwritten in an cló Gaelach – go raibh míle maith agat, a Sheáin. I am indebted to Dominic Carroll, a friend indeed.

My appreciation as always to the gallant archivists and librarians: Brian McGee and crew at the Cork City and County Archives; the staffs of Cork City Library, the National Archives, the National Library of Ireland, University College Dublin Archives Department, the UK National Archives, Trinity College Dublin Manuscripts and Archives, the British Library, the Imperial War Museum and the Irish Examiner Archive. Special thanks to Dan Breen at the Cork Public Museum; to Niall Bergin and Aoife Torpey at the Kilmainham Gaol Museum/OPW; to all at the Boole Library, University College Cork, especially Cronán Ó Dubhlinn for going the extra mile; to Cécile Gordan and Daniel Ayiotis at the Irish Military Archives and to Andrew Martin at Irish Newspaper Archives.

Finally, my gratitude to all at Mercier Press for getting the job done so well under pressure (my fault!), and especially to the indomitable Mary Feehan.

Abbreviations

AOH-BOE: Ancient Order of Hibernians-Board of Erin

AOH-IAA: Ancient Order of Hibernians-Irish-American Alliance

AFIL: All-for-Ireland League

CIDA: Cork Industrial Development Association

CYIS: Cork Young Ireland Society

DORA: Defence of the Realm Act

GAA: Gaelic Athletic Association

ILPTUC: Irish Labour Party & Trade Union Congress

INAAVDF: Irish National Aid Association and Volunteer Dependents’ Fund

INNA: Irish National Aid Association

IRA: Irish Republican Army

IRB: Irish Republican Brotherhood

ISRP: Irish Socialist Republican Party

ITGWU: Irish Transport & General Workers’ Union

IWWU: Irish Women Workers’ Union

LLA: Land and Labour Association

OBU: One Big Union

PLG:Poor Law Guardian

RIC: Royal Irish Constabulary

UIL: United Irish League

UVF: Ulster Volunteer Force

‘Utter disloyalist … A notorious and irreconcilable revolutionary, who has taken an active part throughout his life in every rebel and revolutionary movement in Ireland.’

British army intelligence report on Tadhg Barry, November 1921

Introduction

Tadhg Barry was the last high-profile victim of the crown forces during the Irish War of Independence. A veteran Republican activist, he was a full-time organiser for Ireland’s largest union, the Irish Transport & General Workers’ Union, secretary of its Cork branch and an alderman on Cork City Corporation at the time of his arrest and internment without charge or trial in early 1921. Barry was a well-known public figure, especially in Cork, having been a prominent journalist for many years, as well as a leading Gaelic Athletic Association official, a former Poor Law Guardian, a published poet and the author of the first rulebook for hurling. He had been a founding member of the Irish Volunteers in Cork, a central figure with Sinn Féin in the city both in its initial phase and its second coming after 1916, an elected representative of the short-lived constitutional-nationalist All-for-Ireland League, and an activist in the plethora of Republican/Irish-Ireland organisations that had proliferated in Cork in the first decades of the twentieth century.

He was coming close to the end of his third incarceration (having committed no crime to justify any of them) when he was shot through the heart by a sentry in Ballykinlar internment camp in County Down on 15 November 1921 while waving goodbye to comrades leaving on parole. In 1917 he had served seven months of a two-year sentence in Cork Gaol for making a speech calling for an Irish Republic; in 1918–19 he endured ten months in British prisons, where Spanish flu was rampant, having been arrested for taking part in a non-existent plot with Germany; and in 1921 he was interned in Ballykinlar for the crime of being a leading trade unionist and democratically elected rebel alderman. The sense of sorrow and anger at the cruel death of a widely loved, charismatic character was exacerbated by the timing: weeks later he would have been released along with all his fellow internees as part of the Treaty settlement.

Barry’s death was a huge, but subsequently largely forgotten, event in Ireland. According to the ManchesterGuardian, it excited ‘more popular feeling than anything which has happened since the truce’.1 A Pathé newsreel, A Patriot’s Last Journey, captures a ‘who’s who’ of republican leaders following his coffin in Dublin, including Michael Collins and Cathal Brugha, who would soon become civil-war enemies and victims. Dublin city came to a halt as a quarter of a million people lined the streets and the Dublin IRA had its last full mobilisation before the Treaty split. The funeral in Cork echoed those of Barry’s comrades, the martyred lord mayors Tomás MacCurtain and Terence MacSwiney.2 Irish newspapers were filled with reports of his death, his funeral and the overwhelming national, and even international, reaction. Cork Corporation called for the Treaty negotiations to be suspended. It seemed as if Tadhg Barry would join the pantheon of Irish-republican martyrs. Instead, his name is now little known, meriting at best one or two lines or a footnote in most historical accounts. He was also quickly erased from collective memory, even in his native city.3

Why was Tadhg Barry largely forgotten? Clearly, timing is everything in these circumstances. The Anglo-Irish Treaty was signed three weeks to the day after his death and this quickly monopolised attention; the united movement that elevated him to hero/martyr status was ripped asunder in the ensuing Treaty split and civil war, and the name of Tadhg Barry became lost in the smoke. Poignantly, he had written in December 1918 from Usk Prison that he did ‘not mind dying in gaol if it will do good’, and in a piece of verse composed in Ballykinlar he prophetically wrote:

And though home thoughts come thronging

I’d rather still die here,

And know that so by dying

I was making Ireland free,

When in my grave I’m lying

Near rebel Cork’s city.4

He did die there, but it did not make ‘Ireland free’, nor even do any ‘good’, beyond offering advanced nationalist Ireland the opportunity for a final, united show of strength. It was a tragic and futile end to a life lived proudly as – in the words of a British army intelligence report – an ‘Utter disloyalist’.5

The term ‘Irish revolution’ has become the most widely used umbrella term to cover the political change, social up- heaval, cultural ferment and military conflict that occurred in early twentieth-century Ireland. Its limitations as an ‘actual’ revolution have been well rehearsed and recently analysed in detail by Aidan Beatty, who emphasises its conservative nature and foregrounds continuity within the capitalist/colonial order over any ‘change’ that was brought about.6 Its use here does not imply a misunderstanding of its less-than-revolutionary nature in socio-economic terms, or of its conservative outcomes but, rather, is a recognition of how it was experienced by protagonists like Barry and the radical possibilities that arose in its midst as recognised by an activist who operated across its many fronts. A secret tribute from the British army in Cork after his death called him a ‘notorious and irreconcilable revolutionary, who has taken an active part throughout his life in every rebel and revolutionary movement in Ireland … He was a mischievous socialist, bolshevist, or Sinn Feiner as the occasion demanded.’7 His enemies seemed in little doubt, at any rate, that they were dealing with a revolutionary!

There has been an increasing recognition in recent years of the centrality, perhaps even primacy, of collective action in achieving political change in early twentieth-century Ireland, and a corresponding move away from the so-called ‘great man’ (and, to a lesser extent, ‘great woman’) approach, which is most associated with the genre of biography.8 Barry would have laughed at any ‘great man’ allusions; he was famously modest and unassuming. This biography does not seek to elevate him or present him as other than what he was, using where possible his own words and those of his comrades and colleagues to provide an account of his thinking and activities at different junctures. The aim is to establish a rounded picture of a fascinating activist’s evolving politics and activism; in so doing, it ‘uses’ him to explore the dynamics of the long revolution as they played out, mainly in Cork, which was transformed from a colonial city into the cockpit of a national revolution during the course of his adult life. His story provides insights not only into the multifaceted nature of the broad revolutionary movement, but also into the anti-democratic and coercive nature of the British state in Ireland when its legitimacy was challenged.

Biographical treatments that present the subject’s life chronologically in a narrative structure continue to serve a function, not least because they remain the most popular genre of historical writing – witness, for example, the extra- ordinary success of the Dictionary of Irish Biography project. Historical biography’s key attraction is that it can humanise history and offer an opportunity to understand complicated past events through the personal encounters of a particular individual with those happenings; this can be reductive and/or distorting, but if approached with an awareness of the structural dimensions of historical continuity and change and an informed perspective on how individual agency interrelates with the collective, the results can be illuminating both in terms of the biographical subject and the broader historical context. Beyond that, biographies of lesser-known, ‘second-tier’ figures like Tadhg Barry allow more attention to be paid to liminal and marginal issues and debates that may get lost in biographies of leading figures whose roles in key events suck the attention towards the centre stage.

I make a conscious effort to avoid the common pitfalls of historical biography, such as exaggerating the subject’s influence or identifying with them to the point of losing critical distance, though I may occasionally sin in this regard. Barry’s acquaintance with so many of the leading revolutionary figures and his uncanny knack of being present at significant historical moments lend him a Zelig-like quality at times, while his decency and generosity combined with his cheeky wit, sarcastic edge and rebel spirit make it hard not to like him – especially for a fellow Corkonian.9 This is countered for this biographer, however, by his masculinist militarism, Irish-Ireland exclusivism and Catholicised Victorian moralising – so hopefully a balance is struck! These were common characteristics of many or most of his revolutionary generation, of course, and his views are presented critically in their historical context and not dismissed anachronistically from a ‘liberal’ twenty-first-century perspective or with the ‘enormous condescension of posterity’.10 His socialism and working- class identity were less typical of the so-called revolutionary elite, which created some tensions that shed interesting light on aspects of the history of the cultural revival and of the revolution, especially in a Cork context.

The lack of sources relating to the private individual prevents any in-depth treatment of Barry’s personal life. The focus is on the public person: the political animal, the journalist, the propagandist, the sports administrator, the cultural activist, the soldier, the trade-union organiser, the public speaker and representative. If more details were available about his private life, then a different book might have emerged that embraced more social and emotional history and allowed for a rounded portrait of a short life beyond the public/political. As it is, however, we will be neither standing on the shoulders of a giant and viewing events from a great height, nor burrowing into the domestic life of a romantic revolutionary. Rather, we will be hitching a lift on a winding, bumpy road with a small, pugnacious patriot and proud proletarian, ‘a characteristic product of Rebel Cork – courageous, kindly, generous to a fault, bold and daring, and independent in speech and action’.11 Our journey will reveal familiar landscapes, but also lesser-known terrain, including glimpses of the roads not taken.

1

’Neath Shandon Steeple

Timothy (Tadhg) Barry was born on 25 February 1880 and grew up on Blarney Street, on the Northside of Cork’s River Lee, in the shadow of Shandon’s famous steeple of the church of St Anne. Cork’s longest thoroughfare, with almost 400 houses and eighteen adjacent lanes, Blarney Street was a thriving, bustling neighbourhood – described by Barry, with typical literary flourish, as a ‘crowded purlieu’ – that would become a stronghold of militant Republicanism in the second decade of the twentieth century.1 The vast majority of the Barrys’ neighbours were Catholic and working class or lower middle class. They were vintners and shopkeepers, cattle dealers and pig buyers, factory workers and dock labourers, blacksmiths and farriers, seamstresses, dressmakers, upholsterers and domestic servants, masons and railway workers, shop assistants and bar workers, barbers, porters, watchmen, weighmasters, shoemakers, coopers, shirtmakers, dairymaids, together with a smattering of clerks, insurance agents and teachers.2

Timothy Joseph, as he was christened – he began using the Irish version of his forename, Tadhg, in 1906 – was the fourth child of Margaret (née Murphy) and Daniel Barry. Of his three older siblings, only one, Mary Kate, two years his senior, survived into adulthood, while at least three of his younger brothers and sisters also died as young children, highlighting the precariousness of life prior to the wide availability of vaccines and the discovery of antibiotics and other life-saving medicines. His eldest brother James died aged five from scarlet fever in December 1880, when Tadhg was ten months old, followed two years later by his sister Elizabeth, also aged five, who died from diphtheria. Daniel (b. 1881) survived, later emigrating to South Africa, but the next-born, Margaret, died at three months due to hydrocephalus, or ‘water on the brain’. The twins, Patrick (Paddy) and George, were born in 1885, but the latter only lived until May 1887, when he died from complications arising from a stomach infection.3 Paddy survived into adulthood but suffered with poor health throughout his life.

Faith, fatherland and socialism

Tadhg’s father, Daniel senior, was a cooper, a strong tra- ditional trade in that area of Cork linked to its long- established butter, provisioning, brewing and distilling industries. As with most of his generation in that era, he supported the constitutional-nationalist movement’s campaign for Home Rule; he was well known and well liked in his neighbourhood and was a Home Rule-party activist; he was a member of the Cork committee formed in December 1890 to support the William O’Brien and John Dillon-led anti-Parnellite faction in the Parnell split.4 His son later worked for O’Brien’s Cork Free Press and was elected a Poor Law Guardian (PLG) under an O’Brienite banner in 1911. Tadhg Barry eschewed the traditional route of eldest (surviving) sons of tradesmen by not following in his father’s coopering footsteps. Later in life, as a trade unionist, he railed against the closed-craft system that operated in many of the trades – an antiquated arrangement that privileged some on hereditary lines. ‘A boy’, he wrote in 1918, ‘no matter what his father might be – [should] be entitled, by acquisition of technical knowledge, to perfect himself in the handicraft that gives best promise to his talents.’5 Barry’s talents lay mainly in journalism and organising, and he later excelled at both, as we shall see.

He was educated in the National school on Blarney Street and then at the North Monastery Christian Brothers secondary school, a fifteen-minute walk from his home. The ‘North Mon’, or simply ‘the Mon’, counts among its alumni the later Republican lord mayors of Cork Tomás MacCurtain and Terence MacSwiney, Cork IRA leader Seán O’Hegarty and his brother, the Sinn Féin intellectual and propagandist P.S. O’Hegarty. The latter claimed that his generation of activists ‘owed their first conscious impulse towards aggressive Nationalism’ to the brothers in the Mon, but the conventional assumption that the brothers were somehow responsible for ‘producing’ the revolutionary generation is now a matter of debate.6 It is more likely that those who went on to form the revolutionary elite in urban areas just happened to be those who were typical Christian Brothers pupils of this period – clever, ambitious boys from skilled working-class and lower-middle-class Catholic backgrounds whose parents regarded education as a route to upward social mobility. Whatever about the broader picture nationally, it seems clear that the Mon typified the faith-and-fatherland approach taken in at least some Christian Brothers schools in this period, whereby an emphasis on an Irish-nationalist interpretation of Irish history complemented Catholic indoctrination and Victorian classical education aimed primarily at preparing young men for the British civil service.7 A particularly formative influence on Barry was the Mon’s Brother Clifford, with whom he maintained a lifelong friendship. Originally from Castleisland, County Kerry, Clifford was an ardent advanced nationalist who ended his religious instruction classes with a call for ‘three Hail Marys for the welfare of Ireland, for the advancement of the Irish language, and that we may die for Ireland’. He also taught a number of selected students, many of whom ended up as Volunteers, how to use a gun, bringing them for shooting practice after school with his .22 rifle.8 In the early years of the new century, however, the brothers in general were seen by Irish-Irelanders as an ‘enemy of Gaelic culture’, primarily because of the playing in their schools of ‘foreign’ (that is, British) games, especially rugby.9 The Mon was among them and Barry was involved in the successful campaign to extend Gaelic games to schools and colleges, including his alma mater. This was regarded as essential to, in the words of Republican and Gaelic Athletic Association (GAA) official Thomas F. O’Sullivan, ‘saving thousands of young Irishmen from becoming mere West Britons’ and, in Barry’s own words, ensuring the GAA’s place in ‘the fight for national regeneration’.10

Whether the brothers ‘produced’ a generation of re- volutionaries or not, they certainly cemented the Catholic- isation of Irish nationalism among many of this cohort. Religion was as central to Barry’s identity as was his Irish nationalism, local patriotism and his class; in his youth he served as an altar boy at the local St Vincent’s church, and later as a mass attendant, and was active in the Catholic charity work of the St Vincent de Paul Society. However, he consistently opposed religious sectarianism in politics, epitomised for him above all by the Ancient Order of Hibernians-Board of Erin (AOH-BOE), a component of the Home Rule movement that became an immensely powerful force in Irish politics and society from 1907 to 1918. His hatred for this political faction led him to politically identify for a period with its key opponent in the constitutional nationalist field, William O’Brien’s All-for-Ireland League.

Catholicism and Irish Republicanism coexisted com- fortably for most Irish rebels of this era, and for a fewer number, Barry among them, a socialistic outlook was added to the mix – essentially an advanced-nationalist syndicalism based on James Connolly’s late-career approach, wrapped in the Catholic social principles of the 1891 papal encyclical Rerum Novarum. While Barry’s labour Republicanism was centred on the trade-union movement (and, for a time, the labour-nationalist element in the All-for-Ireland League), it later entailed a rhetorical support for the Bol- sheviks when they seized power, and for the red flags and slogans of post-war international socialism, but not an ad- herence to the full spectrum of Marxist, and certainly not Marxist-Leninist, ideology. His devout Catholicism fused with a generalised left-wing analysis and labour activism to make Barry a Christian socialist, a worldview epitomised in these lines from his final published poem, ‘The Future War’: ‘And we’ll teach the boss that the Bible says/ Go share with the poor your all’.11 (See Chapter 4 for a discussion of Barry’s Christian socialism.)

We do not know the context for his initial interest in socialist ideas, but it is possible that the source was Con O’Lyhane (aka Lyhane and, later, Lehane), the charismatic and colourful organiser of Cork’s Fintan Lalor Club, a branch of James Connolly’s Irish Socialist Republican Party (ISRP), between 1899 and 1901. It is known that Barry was a regular attendee at the debating guild of the Catholic Young Men’s Society in its rooms on North Main Street, a popular forum in the city at the turn of the century, where O’Lyhane was a star performer. Liam de Róiste re- called him as ‘a very fluent speaker, a good debater, ready in argument, pugnacious, aggressive, unshakeable in his opinions. He presented the case for Socialism with logic and force.’12 While he failed to convince the conservative de Róiste, it is entirely plausible that the young Timothy Barry would have come under his spell. He may also have been among the large attendance at Connolly’s lecture on ‘Labour and Irish Revolution’ in the city in February 1899 and, as a voracious reader, was likely familiar with the party’s Workers’ Republic, which briefly sold well in the city in late 1901. The ISRP in Cork was subjected to a barrage of clerical condemnation, including a bishop’s letter; O’Lyhane lost his job as a butter-merchant’s clerk as a consequence in late 1901 and emigrated first to London, where he was a prominent socialist activist, and later to the US, where he also cut a dash in left-wing circles. He clashed with Connolly over what he saw as the latter’s failure to take on the Church, scornfully referring to him as ‘Catholic Connolly’. Writing on the issue of socialism and religion in 1916, Barry, in a rare, if sideways, criticism of the Church, commented that ‘Con Lehane was driven from his home because he believed the redistribution of wealth to be the fundamental principle. Those who drove him forth saw in his ideals the doctrines of Karl Marx.’13

Exile, return and the genesis of Sinn Féin

Barry’s first steady job, as far as is known, was as an attendant at the Eglinton Asylum (later Our Lady’s Hospital) on the Lee Road, half-an-hour’s walk from his house. He started work there in April 1899 as a third-class attendant and was promoted to second-class attendant in November 1902.14 He was a member of the Asylum Workers’ Union and even after he left the job continued to write for the union’s journal. He later recalled objecting to the use of inmates and attendants to do essential works, such as painting in the asylum, rather than employing unionised painters. He would go on to serve on the board of management of the institution following his election to Cork Corporation in January 1920, where his inside knowledge of its workings proved invaluable as he fought to eliminate corruption and bad practices and to promote better conditions for the patients. While employed there he organised concerts involving staff and inmates to raise funds for the infant Gaelic League in the city. He also established a Gaelic football team among the asylum staff and was a member of the local St Vincent’s GAA club; a contemporary recalled that he was ‘not a great player. He was often relegated to the side-line.’15 He studied part-time and gained some qualifications, probably of a clerical nature, and in July 1903 resigned from his asylum job and took the well-trodden emigrant path to Britain, first to the Yorkshire port town of Hull and then on to London.

He was living in the Bloomsbury district of London in July 1906 when he purchased five £1 shares in the Sinn Féin Printing and Publishing Company, which had been established by the doyen of advanced-nationalist propa- gandists Arthur Griffith and others in April 1906 to fund the publishing of a new weekly paper, Sinn Féin; Griffith’s previous paper, the United Irishman, had folded following a libel action.16 The share drive was a modest success, with only 167 being sold in its first two years. Most of the funds came from the sale of £5 debentures purchased in significant quantities by wealthy sympathisers like Edward Martyn and Roger Casement. The paper was published weekly from 1906 to 1909; following the failed daily Sinn Féin experiment in late 1909, it resumed as a weekly in 1910 until its suppression in 1914.

We know little or nothing about Barry’s English years, but he was obviously active in the GAA in Hull, recalling years later the difficulty of having to go ‘seventy-five miles across Yorkshire’ to make up the numbers in a team.17 A friend from that time recalled that ‘his thoughts were always over here [in Cork]’, and this is clear from his nineteen-verse emigrant paean to his native city, ‘Memories of Cork’, penned in Hull: ‘From Blackpool to sweet St Barry’s, o’er each spot my memory tarries/ The Park, the Marsh, South Gate and Patrick’s Hill …’18 He wrote later that ‘Those of us who have lived in foreign lands know how different the surroundings seemed once we got into a Gaelic League room or a Sinn Féin club’, suggesting that his time there followed the familiar pattern of the separatist emigrants of that era, like his North Mon contemporary P.S. O’Hegarty and the younger Michael Collins.19 In the words of Darragh Gannon, the League provided ‘an Irish-Ireland haven for emigrants in the often unfamiliar, lonely and, at times, intimidating surroundings of the London metropolis in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.’20 Barry does not feature in the annual reports of the Gaelic League in London in this period, which suggests only that he was not an officer – he may well have been an ordinary member.21 While we also have no direct evidence that Barry was a member of the London GAA, he almost certainly was, given his lifelong enthusiasm for Gaelic games and a later comment about his experience of hurling matches in London, where cockneys sneered at the ‘dirty Irish’.22P.S. O’Hegarty was in London at this time also, and in 1907 wrote the following, which echoed Barry’s words quoted above and surely also his feelings:

None save those who have experienced the bitterness of exile will understand the place which the GAA occupies in the hearts of the London Gaels … When we enter the Association ground at Lea Bridge, on Sundays, we leave behind us a week spent in a foreign country and enter again into our own civilization, no ‘Bills’ in evidence, Gaels everywhere, clean-living, hard-hitting Gaels. And as we punt the football, or swipe at the elusive ‘slitter’, we forget that we are exiles.23

As was the case in Cork and elsewhere, the Gaelic League in London, of which O’Hegarty was a stalwart, was a hub around and out of which a variety of other cultural and political initiatives were generated, including the GAA, the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB) and its Dungannon Clubs, which became a constituent part of the new Sinn Féin party in 1907. Barry left London in the autumn of 1906 and is first mentioned in the press of his native city in September of that year attending a meeting of the Cork Celtic Literary Society (see below); in the following month he was a founder member and joint honorary secretary of the newly established Cork branch of Arthur Griffith’s National Council (of Sinn Féin), which became a constituent part of the new Sinn Féin party a year later.

The genesis of the Sinn Féin movement in Cork lay with a group of young Republicans who became active in cultural organisations in the city at the turn of the century; they were part of a nationwide revival in separatist and Republican politics that overlapped with and fed off the cultural revival in the years around the centenary of the 1798 Rebellion. In 1899 members of the city’s Gaelic League branch formed the Cork Young Ireland Society (CYIS) ‘to aid in the attainment of Ireland’s sovereign independence’ by disseminating Young Ireland ideas and countering ‘West Britonism’ in every form. The CYIS organised a large pro-Boer public meeting that led to the formation of a local Transvaal Committee. It also ran classes and concerts, and began the process of fundraising for a national monument on the city’s Grand Parade to replace the prominent statue of King George II that had stood at the river end of the street until the 1860s. The National Monument memorialising the rebels of 1798, 1801, 1848 and 1867 was eventually unveiled in 1906 and became a focal point for political gatherings in the city. However, the CYIS had suffered a split at the end of 1900 when five of its younger members left: Terence MacSwiney, Liam de Róiste, Dan Tierney, Fred Cronin and Bob Fitzgerald were frustrated by what they saw as the backward-looking priorities and lack of transparency of the older, conspiratorial Fenian cohort in the group. In January 1901, along with Batt Kelleher and Michael Radley, they established a new organisation called the Cork Celtic Literary Society.24 Despite its name it was, as local Redmondite J.J. Horgan recalled, ‘more revolutionary than literary in its aim’, which was, in essence, ‘To strive for the establishment of an Irish Republic’.25 The original Celtic Literary Society had been established in Dublin in 1893 by William Rooney to promote Irish culture and ‘independent political action’. The Celtic, as it became known, immediately became the Cork affiliate of Cumann na nGaedheal, an umbrella organisation of counter-anglicisation politico-cultural groups and societies launched by Arthur Griffith and William Rooney in September 1900, with veteran Fenian John O’Leary as president.

The Celtic, which Barry joined on his return to Cork in 1906, was a small (its membership never exceeded thirty) but determined group of Irish-Ireland activists. As well as running classes in the Irish language, history and dancing, and organising excursions, outings and socials, it hosted lectures, produced a monthly manuscript journal called Éire Óg (Young Ireland) and successfully campaigned for bilingual street signs and the renaming of bridges after Irish patriots rather than British figures – part of a nationwide process of ‘reclamation’ of public space that became a key element of the de-anglicisation project. It protested against the frequent royalist gestures of Cork Corporation, campaigned for the closing of pubs on St Patrick’s Day (‘Ireland Sober, Ireland Free!’) and held protests against stage-Irish productions in the Opera House. In 1902 Maud Gonne visited Cork to establish a branch of Inghindhe na hÉireann, the women’s nationalist organisation affiliated to Cumann na nGaedheal that she had founded in Dublin in 1901 because women were excluded from membership of most of the existing nationalist organisations. Inghindhe na hÉireann shared premises and collaborated in many areas with the Celtic, and in February 1902 Gonne was made its honorary president. The Celtic pushed for Cumann na nGaedheal to adopt an unambiguous Republican position, but this was opposed by Griffith, who insisted on its object being ‘sovereign independence’; the Cork proposal was defeated, and it presaged future disagreement between Republicans and Griffith, who was studying international precedents to find a novel approach to securing independence.26

Griffith’s so-called ‘Hungarian policy’ was developed in a series of twenty-seven articles in his United Irishman paper in the first half of 1904; it was published as The Resurrection of Hungary: A Parallel for Ireland later that year. Its central argument was that Irish nationalists should follow the example of their Hungarian counterparts, who had secured autonomy within the Habsburg empire in 1867 through a campaign of passive resistance and the withdrawal of their representatives from the imperial parliament in Vienna. The settlement involved a ‘dual monarchy’ whereby Hungary and Austria were separate but subject to the one king; Griffith proposed a similar solution involving Ireland and Britain. He also developed wide-ranging ideas for Irish self-sufficiency in what would become known as his Sinn Féin (We Ourselves) policy, but it was the central political tactic of elected representatives withdrawing and abstaining from Westminster and establishing independent Irish political structures that gained most traction and was seen as a fruitful idea by Republicans like Barry, despite their distaste for dual monarchy. These marginalised political ‘beggars’ could ill-afford to be ‘choosers’ as they awaited a critical mass of support for armed separatism. As we shall see, once first-phase Sinn Féinism reached a political cul-de-sac by 1910, Barry took a diversion that most of his city comrades did not when he hitched his wagon to the most promising nationalist challenger to Redmondism in the shape of William O’Brien’s All-for-Ireland League.

‘The hand that flung the battle spear was trained at the camán’27

In 1903, the year of Barry’s departure for England, the Celtic had achieved its two most important successes: the establishment of a hurling club, Éire Óg, and the initiation of a committee to promote industrial development in Cork that would become the pioneering Cork Industrial Development Association (CIDA). The CIDA, of which Barry would become a long-time executive member, was founded in April 1903 following an initial meeting called by the Celtic in February. It brought together a diverse range of local figures from political, business and trade-union circles to promote industrial development and forge international investment and market links. It encouraged consumers to buy locally produced goods, patented the ‘Déanta i nÉireann’/‘Made in Ireland’ trademark that was adopted by Irish-Irelanders nationally and later by the Free State, and organised annual industrial exhibitions. Its most famous success was the establishment of the Ford factory in the city in 1917.

Éire Óg was one of the vehicles used by these Cork Republican activists – many of whom would become IRB members – to take control of the GAA in the county. The previous IRB takeover of the GAA in the late 1880s had been disastrous and counterproductive, effectively splitting and almost fatally weakening the organisation in the aftermath of the Parnell split. This time there was a realisation that, if it were to succeed as a national organisation and, by extension, feed into the movement for Irish independence, the GAA first had to be transformed so that it would attract players and supporters, and should tread carefully in a political sense so as not to alienate potential members and supporters.

At both the national and local level the GAA was in a poor state in the early years of the twentieth century. A dwindling number of clubs, lack of enclosed pitches and turnstiles, poor facilities, mismanagement, lack of punctuality among teams, serious ill-discipline (including frequent ‘pugilistic encounters’) among players, lack of uni- formity in jerseys and inconsistent and poor refereeing had seen the games lose both players and public support at the expense of better-run alternatives like rugby and soccer. Although a new generation of enthusiastic officials headed by Jim Nowlan (president) and Luke O’Toole (secretary) had taken over at national headquarters in 1901 and had begun the process of reform and regeneration that would see the organisation transformed, it required the energy and commitment of local activists to make the initial difference. As in Cork, many of those who took the initiative around the country – Harry Boland in Dublin, Austin Stack in Kerry, Cahir Healy in Fermanagh, Charlie Holland in Limerick – were also Republicans who would later feature prominently in the Irish revolution. Cork’s Republican-reformist team of administrators, which began to organise in 1904 as the Cork City and County Reform Committee, GAA and, later, as the self-styled ‘Progressives’, was headed by J.J. Walsh of Éire Óg. Other members included J.F. O’Leary, Micky Sullivan, brothers Paddy and Mick Mehigan and Tadhg Barry.

They shook up the moribund organisation in the county, mainly by establishing independently of the county board a series of new football and hurling cups and leagues, beginning with the Cork Hospitals Cup in 1907; Barry served on the Hospitals Cup Committee, which, one contemporary recalled in 1921, ‘did much in placing the G.A.A. in the proud position that it occupies today’.28 They also encouraged the establishment of new clubs. In 1908 Barry was a founder member of a dynamic new hurling club, Sunday’s Well, and he became one of its two delegates on the Cork County Board in 1909, the year that J.J. Walsh’s election as chairman announced the effective takeover of the county organisation by the Progressives.

In a 1909 ‘Review of Gaelic Work in Cork’, one of the group, J.F. O’Leary, noted that, as well as the factors outlined above, GAA reformers in Cork faced a hostile local press and a well-organised local rugby scene that was nourished by its dominance in the Christian Brothers and Presentation Brothers schools as well as in University College Cork and other third-level institutions. Underlying it all, wrote O’Leary in the classic Irish-Ireland rhetoric of the time, was the fact that much of the population was ‘afflicted with that disease called “classy notions”, the Johnny, the toff, the well dressed cad, the shoneen, the ape, the jelly fish and similar fry love to despise everything belonging to their own country and are anxious to adopt the games and manners of their conquerors’.29

More leagues and competitions were organised and more clubs founded; a paper that gave prominent coverage to the GAA, the Cork Sportsman, was established in 1908 and it featured Tadhg Barry’s first forays into sports journalism; turnstiles were installed at all major venues, which led to increased gate receipts; professional accountancy measures were introduced, more income allowed for more improve- ments, public confidence grew and so, too, did participation and public support. As well as creating a successful sporting organisation, Walsh, like Barry, had no doubt about the GAA’s role in whipping young Irishmen into the required mental and physical shape for the independence struggle to come, asserting in his memoirs that ‘The work put in by this band of enthusiasts bore a rich harvest in the sub- sequent fight for freedom, in which County Cork played a magnificent part.’30

The GAA was a central and important part of Barry’s life. In politico-cultural terms he viewed it as integral to the ‘national regeneration’ project, but he also simply loved the games, especially hurling. According to his comrade Nora Wallace, ‘nothing suited his fiery, impulsive and boyish spirit better than the wild dash for the ball, and the sound of camán meeting leather was balm to his soul.’31 For him hurling was ‘Ireland’s historic and unexcelled game’ and he was not alone; to most enthusiasts at that time (and, indeed, in the present day), hurling possessed quasi-spiritual, artistic qualities. GAA founder and sports journalist Michael Cusack summed it up in the following passage that would have resonated with Barry:

Is Hurling a Fine Art? I think it is. I know nothing except the Irish Language that gives more pleasure to those who take part in it, or to those who concentratingly observe it. The mighty spirit of Tolstoi was not more refreshed by his first sight of the mountains after his journey over the vast plains of Russia, than is the soul of a true-born hurler at the sight of a good hurling match. When I reflect on the sublime simplicity of the game, the strength and swiftness of the players, their apparently angelic impetuosity, their apparent recklessness of life and limb, their magic skill, their marvellous escapes, and the overwhelming pleasure they give their friends, I have no hesitation in saying that the game of hurling is in the front rank of the arts.32

The Well

Sunday’s Well, which absorbed the existing St Vincent’s minor hurling cohort at its foundation in 1908 (minor at that time referred to the lowest level of the game rather than underage), drew its players primarily from the Blarney Street area; according to Nora Wallace, Barry was its main recruiter. Sunday’s Well Rugby Club had been founded in 1906, signalling that game’s popularity among the youth of the area. Soccer was also thriving on the city’s Northside, and the need for a Gaelic counter-attraction was keenly felt by Barry and his fellow enthusiasts. The Well’s most famous alumnus was Seán Óg Murphy, who, as a youngster, was championed by Barry and went on to become one of the game’s greatest full backs. It was he who insisted on giving the young Jackie Murphy a chance; when the other Well selectors thought him too physically slight, Barry judged him – rightly, and in classic GAA parlance – to have ‘the makings of a great little hurler’. He christened him ‘Sean Óg’ after the legendary Limerick hurler Seán Óg Hanley of Kilfinane. Murphy went on to have a hugely successful career with Blackrock and Cork, winning three All-Irelands and five county championships, among much else.33

Sunday’s Well was a vibrant presence for several years at the minor level of Cork hurling and was an important factor in popularising hurling on the city’s Northside at a formative period. Hurling in Cork was dominated by the three senior clubs of Blackrock, St Finbarr’s and Red- mond’s (the Rockies, the Barrs and the Reds), all based on the Southside. The significant Northside clubs of Brian Dillon’s and The Glen were not formed until 1910 and 1916 respectively, and Na Piarsaigh, an offshoot of the North Mon, not until 1943, the same year as the revived St Vincent’s. The Well was one of a number of new small clubs that emerged on the Northside and, like its great local rival St Mary’s of Blackpool, also fielded juvenile teams. According to one local newspaper, The Well ‘never shirked a contest’ no matter how much travel was involved, and its participation in ‘invitation matches with young county clubs has given zest to the game and infused enthusiasm into new adherents, which ended in the formation of permanent clubs’.34 According to a Cork GAA contemporary, Barry ‘went with them everywhere. He wrote glowing descriptions for the Press of their achievements and he eulogised them in poetry.’35 Competition with other sports, emigration and the poaching of players by senior clubs made The Well’s survival precarious. In late 1912 Barry wrote bitterly that ‘the transfer cancer, together with the anti-national games and emigration have affected the well-known club to such an extent that few of the old brigade are left; but what remains is proof that traitors and deserters are no loss’. Within two years, however, those losses proved too much to bear and the club had effectively disappeared.36

Barry was also an early supporter of camogie, the women’s version of hurling, which began in Cork shortly before his return from London. The first-ever camogie match was played at a Gaelic League event in Navan in June 1904, and Cork’s first club, Fáinne an Lae, was established in the summer of 1905 in Barry’s bailiwick of Blarney Street by May Conlon, Annie Walsh and her sister Eilís, who later married Tomás MacCurtain. On his return, Barry and May Conlon’s brother Seán trained the team. At that stage the Walshes had established a second team in Blackpool, Clan na Gael, allowing Cork’s first camogie match to be played at the O’Neill Crowley Grounds at Victoria Cross in 1906. More clubs followed and by 1911 camogie was firmly established. In that year An Cumann Camógaíochta was founded in Dublin and games began to be organised by the GAA Cork County Board. In his book on the rules of hurling, privately published in 1916 and publicly issued in 1920, Barry specified that ‘Camogie players will find the suggestions adaptable to their own branch of the game, the root-idea being the same’.37

Strongholds of anglicisation

The campaign to ‘rescue’ schools and colleges from the grip of ‘foreign games’ became a major battleground in the cultural war against anglicisation. The GAA’s notorious ‘ban’ – which included the rule forbidding members from playing or attending non-GAA sports, as well as that deny- ing membership to members of the police or crown forces, a rule that Barry vigorously promoted – did not extend to schools and colleges in the hope that this would facilitate the gradual introduction of Gaelic games into these institutions, where rugby and cricket held sway. Gaelic com- petitions for Cork schools began in 1902, but by then rugby had long been the chosen sport of the city’s three main Catholic schools: Presentation Brothers College, Christian Brothers College and the North Mon. The rugby- and cricket-playing tradition and culture were deeply ingrained and, according to the 1911 Gaelic Athletic Annual, produced in the students ‘during their formative years, a prejudice in favour of the carefully fostered alien games, on the one hand, and a strong antipathy to the neglected and despised national games on the other’.38 Furthermore, according to J.F. O’Leary, the Cork Catholic schools’ embrace of rugby had the effect of increasing that game’s broader popularity as these schools were ‘generally believed by the man in the street to be models, worthy of emulation’.39 The campaign to Gaelicise the sporting culture of schools and colleges yielded gradual success. Munster led the way and, by 1911, many of these ‘strongholds of anglicisation’ in the province had been ‘attacked and conquered’, but the war would be a long one.40J.J. Walsh, along with Barry and others, in- cluding a number of sympathetic brothers in the school, maintained a steady campaign to pressurise the Mon to embrace Gaelic games, but it did not do so until 1916, despite reports to the contrary that appeared sporadically in the local press. As we shall see, that development was one that brought immeasurable joy to Barry in a fateful year that was otherwise characterised by dashed hopes and tragedy.

More infallible than the Pope

Barry was an enthusiastic GAA administrator who was constantly seeking ways to expand the organisation in the city and county. He was a founding vice-president and honorary secretary of the inaugural Saturday Hurling League in Cork, a new departure that began in November 1908 and proved highly successful. Matches were usually played on Sundays, but the Saturday development helped the GAA to compete directly with soccer and rugby on their more usual match day. In August 1909, following the completion of that season’s Saturday League, Barry convened a meeting to inaugurate the Sunday Hurling League, of which he became chairman. He argued that ‘The success of the Saturday League shows that proper management alone is needed to make the project one which will not only be a financial success but a training ground for those to whom the honour of Cork county will have to be entrusted in the near future.’41 He was well known as a referee and served for a period as secretary of the county’s Referees’ Association. Poor refereeing continued to dog the GAA and damage its reputation, and Barry was ardent about the importance of consistency and high standards. He brought forward a recommendation to the county board in April 1911 on behalf of the Referees’ Association that when the GAA’s new rules were adopted, referees should have to pass an examination before being awarded certificates. The idea was initially met with laughter and scorn, but Barry insisted that he was serious and the motion was brought to the GAA’s national convention. In his book on hurling he made clear, tongue-in-cheek, how elevated a vocation it was: ‘Above all, remember that a referee on the field is more infallible than the Pope. The latter has to consult others before giving judgement. The referee consults no one.’42 He also brought his characteristic wit to the job itself. On one occasion – which showed that, despite improvements, the GAA was still organisationally a work in progress – he was refereeing an intermediate hurling final in Turner’s Cross between St Finbarr’s and Rangers. The game ended in dramatic circumstances: Rangers were well ahead and extended the lead when a free was driven between the posts. The sliotar flew across the Curragh Road and into a field on the other side; a youngster picked it up and ran away towards Douglas. St Finbarr’s had a replacement sliotar but refused to produce it, hoping for abandonment and a replay. After a long interlude, Barry put an end to proceedings when he ‘announced it was time for his dinner!’43

An Ciotóg

It was as a journalist, however, that Barry made his biggest sporting impact when writing a GAA column for the Cork Free Press under the pen name ‘