14,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Parkstone International

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

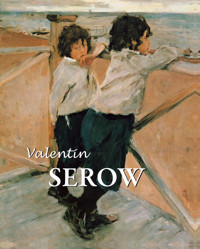

Among the “young peredvizhniki” who joined the World of Art group, the most brilliant portraitist was Valentin Serov. Like many of his contemporaries, he delighted in painting out of doors, and some of his most appealing portraits – such as Girl with Peaches, Girl in Sunlight and In Summer - owe their naturalness to their setting or to the interplay of sunlight and shadows. Indeed, Serov regarded them as “studies” rather than portraits, giving them descriptive titles that omitted the sitter's name. The subject of Girl with Peaches – painted when Serov was only twenty-two – was in fact Mamontov's daughter Vera. The model for In Summer was Serov's wife. When only six years old, Serov began to display signs of artistic talent. At nine years old, Repin acted as his teacher and mentor, giving him lessons in his studio in Paris, then let Serov work with him in Moscow, almost like an apprentice. Eventually Repin sent him to study with Pavel Chistiakov – the teacher of many of the World of Art painters, including Nesterov and Vrubel. Chistiakov was to become a close friend. Because Serov's career spanned such a long period, his style and subject matter vary considerably, ranging from voluptuous society portraits (the later ones notable for their grand style and sumptuous dresses) to sensitive studies of children. Utterly different from any of these is the famous nude study of the dancer Ida Rubinstein, in tempera and charcoal on canvas, which he painted towards the end of his life. Although Serov's early style has much in common with the French Impressionists, he did not become acquainted with their work until after he had painted pictures such as Girl with Peaches.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 129

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2012

Ähnliche

Author:

Dmitri V. Sarabianov

Layout:

Baseline Co. Ltd

61A-63A Vo Van Tan Street

4th Floor

District 3, Ho Chi Minh City

Vietnam

© Confidential Concepts, worldwide, USA

© Parkstone Press International, New York, USA

Image-Barwww.image-bar.com

All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced or adapted without the permission of the copyright holder, throughout the world. Unless otherwise specified, copyright on the works reproduced lies with the respective photographers, artists, heirs or estates. Despite intensive research, it has not always been possible to establish copyright ownership. Where this is the case, we would appreciate notification.

Dmitri V. Sarabianov

Contents

Introduction to Russian Painting

The First Master of Russian Painting

Ilya Repin, Valentin Serov, 1901.

Charcoal on canvas, 116.5x63.3cm.

The State Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow.

Open Window. Lilacs (study), 1886.

Oil on canvas, 49.4x39.7cm.

National Art Museum of the Republic of Belarus,

Minsk.

The sublime imagery of the great icon painters, the portraiture of the 18th and 19th centuries, the paintings of sea, snow, and forest, the scenes of peasant life and the historical works of the Itinerants, the stylishness of the World of Art movement, the bold experimentation of the artists of the early 20th century … To anyone unfamiliar with Russian painting, its richness and diversity may well come as a surprise or at least an exciting revelation.

The Academy of Sciences was established in St Petersburg by a decree of the governing senate on 28 January (8 February) 1724, following an order of Emperor Peter the Great. Peter the Great’s decision to build a capital that would be “a window on Europe” had considerable significance for Russian painting. First, he lured architects, craftsmen, and artists to Russia from various parts of Europe, both to design and decorate the buildings of St Petersburg and to train their Russian contemporaries in the skills needed to realise his plans for modernising the whole country. With similar aims in mind, he paid for Russian artists to study abroad and planned to establish an art department in the newly created Academy of Sciences.

After Peter’s death, these plans reached fruition with the 1757 founding of the Imperial Academy of the Arts, which opened in earnest six years later. For more than a hundred years the Academy exerted a powerful influence on Russian art. It was supplemented by a preparatory school, where budding artists were sent when they were between six and ten years old.

It was rigidly hierarchical, with titles ranging from “artist without rank” to academician, professor, and councillor. Students who had the stamina to do so toiled at their studies for fifteen years. And, until the last quarter of the 19th century, it was dominated by unquestioning acceptance of classical ideas. Russian artists frequently found the Academy’s regulations and attitudes frustrating, but it did have the merit of making a comprehensive and rigorous artistic education available to those who showed signs of talent.

Initially the staff of the Academy included a preponderance of foreign – mainly French and Italian – teachers. As a result, Russian painting during the second half of the 18th and first half of the 19th centuries owed a great deal to the fashions prevalent in other parts of Europe, which tended to reach Russia with some delay.

Given the distance from St Petersburg and Moscow to the Western European capitals, this lag is hardly surprising. But Russian painters did have considerable opportunities to familiarise themselves with Russian and non-Russian art, both thanks to the circulation of reproductions (often in the form of engravings and lithographs) and to the art-buying habits of the ruling class.

As well as funding the Academy (including travel scholarships for graduates), Catherine the Great bought masterpieces of French, Italian, and Dutch art for the Hermitage. During the French Revolution, her agents – and Russian visitors to Paris in general – were able to pick up some handy bargains, as the contents of chateaux were looted and sold off.

However, although the Academy boasted a diverse and fairly liberal collection of foreign masterpieces, not all of the students were content. In 1863 – the year that the first Salon des Refusés was held in Paris – fourteen high-profile art students (thirteen painters and one sculptor) resigned from the Imperial Academy of Arts in St Petersburg in protest against its conservative attitudes and restrictive regulations. Their next move was to set up an artists’ cooperative, although it soon became apparent that a more broadly based and better organised association was needed, eventually leading to the formation of the Society for Itinerant Art Exhibitions.

The Society was incorporated in November 1870, and the first of its forty-three exhibitions was held in November 1871 (the last one took place in 1923). The four artists who spearheaded the Society’s founding were Ivan Kramskoï, portrait, historical, and genre painter, who taught at the Society for the Encouragement of Artists school of drawing in St Petersburg before being given the rank of academician in 1869; Vassily Perov, portrait, historical, and genre painter who taught painting at the School of Painting and Architecture in Moscow from 1871 to 1883; Grigory Miasoyedov, portrait, historical, and genre painter who lived in Germany, Italy, Spain, and France after completing his studies at the Academy in St Petersburg and was one of the board members of the Society for Itinerant Art Exhibitions, and finally, Nikolaï Gay, religious and historical painter, portraitist and landscape artist, sculptor and engraver who also wrote articles on art. First a student of physics and mathematics at the St Petersburg State University, he entered the Academy of Arts as a teacher as of 1863.

One of their primary concerns, reflected in the name of the Society, was that art should reach out to a wider audience. To further that aim – perhaps inspired by the narodniki (the Populists then travelling around Russia preaching social and political reform) – they undertook to organise “circulating” exhibitions, which would move from one town to another.

And like the Impressionists in France (who also held their first exhibition in 1874), the peredvizhniki – variously translated as Itinerants, Travellers, and Wanderers – embraced a broad spectrum of artists, with differing styles and a great variety of artistic preoccupations. But, initially at least, the Society was a more tightly knit organisation, and ideologically its aims were more coherent.

Living at the time when the writings of Alexander Herzen, Nikolay Chernyshevsky, Ivan Turgenev, Fyodor Dostoyevsky, and Leo Tolstoy were awakening social consciences, most of the Itinerants were actively concerned with the conditions in which the ordinary people of Russia lived, and strove to stimulate awareness of the appalling injustices and inequalities that existed in contemporary society. The artistic movement that focused on these concerns came to be known as Critical Realism.

By the Window. Portrait of Olga Trubnikova (unfinished), 1886.

Oil on canvas mounted on cardboard, 74.5x56.3cm.

Peasant Woman in a Cart, 1896.

Oil on canvas, 48x70cm.

The State Russian Museum,

St Petersburg.

Village, 1898.

Gouache and watercolour on paper mounted on cardboard,

25.5x37.5cm.

The State Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow.

During the first quarter of the 20th century, modern Russian painters wished to confer upon art a vaster social resonance. To this end, they had to reconcile the profound attachment of Russians to tradition and the desire for renewal. The latter found expression in a wide variety of movements.

Russian Avant-garde offers multiple facets, drawing inspiration from foreign sources as well as those of its home country, making Russian art the spearhead of the worldwide artistic process at the beginning of the 20th century.

A hundred years or so later, Sergeï Shchukin and the brothers Mikhail and Ivan Morozov purchased numerous Impressionist paintings and brought them back to Russia. In 1892, the merchant and industrialist Pavel Tretyakov gave his huge collection of paintings (including more than 1000 by Russian artists) to the city of Moscow. Six years later, the Russian Museum opened in the Mikhailovsky Palace in St Petersburg. Today it houses more than 300,000 items, including some 14,000 paintings.

Exhibitions, such as that of Tretyakov in the Russian Museum, also played an important role in the development of Russian art. At the end of the 19th century, the artistic status of icons had been in eclipse for approximately two hundred years, even though they were cherished as objects of religious veneration. During that time, many of them had been damaged, inappropriately repainted, or obscured by grime.

In 1904, Rublev’s Old Testament Trinity was restored to its full glory, and in 1913 a splendid exhibition of restored and cleaned icons was held in Moscow to mark the millennium of the Romanov dynasty. As a result, the rediscovered colours and stylistic idiosyncrasies of icon painting were explored and exploited by a number of painters in the first decade or two of the 20th century. Similarly, when Diaghilev mounted a huge exhibition of 18th-century portrait painting at the Tauride Palace in St Petersburg in 1905, it resulted in a noticeable revival of interest in portraiture and in Russia’s artistic heritage as a whole.

International exhibitions (like the ones organised by the Golden Fleece magazine in 1908 and 1909), together with foreign travel and visits by foreign artists to Russia, allowed Russian painters to become acquainted with movements such as Impressionism, Symbolism, Futurism, and Cubism. What is particularly fascinating is to see how artists as diverse as Igor Grabar, Mikhail Vrubel, Marc Chagall, Mikhail Larionov, and Natalia Goncharova adapted these influences and used them to create their own art – often incorporating Russian elements in the process.

Girl with Peaches. Portrait of Vera Mamontova, 1887.

Oil on canvas, 91x85cm.

Portico with a Balustrade, 1903.

Oil on canvas, 49.5x63cm.

The State Russian Museum, St Petersburg.

To assess the creative endeavour of a major artist is to ask what makes him great, what is his main contribution to art? The answers to that question may vary widely. Some artists discover new facets of life, facets previously inaccessible to art. Others develop an entirely new approach to the painting of their time and blaze a trail to new painterly techniques. Still others consummate a whole trend in the evolution of art. Valentin Alexandrovich Serov, who stands apart in the Russian painting of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, was all three – a great reformer, a pace-setter, and an artist who linked two important periods in Russian painting.

Serov began his career in the 1880s, when the realist artists of the Society for Circulating Art Exhibitions were at the pinnacle of their success. His first officially exhibited pictures, Girl with Peaches and Sunlit Girl, were done in 1887-1888. Several years earlier, his teacher Ilya Repin, an active member of the Society, had displayed his Religious Procession in Kursk Province, followed by the canvases They Did Not Expect Him and Ivan the Terrible and his Son Ivan. The foremost Russian history painter of the time, Vasily Surikov, completed his most outstanding creation, Boyarina Morozova, in the same year that Serov produced his Girl with Peaches.

When, on the other hand, the artist was painting his last masterpieces, The Rape of Europa and Odysseus and Nausicaa, Russian art was striving, not to recreate real-life scenes, but to paraphrase life, seeing in the artistic image a self-sustained artistic reality. It was now concerned not so much with analysing the relationship between man and society as with finding a new symbolism, a new mythology, and poetry to reflect the modern world.

This transition to a new set of creative principles that were to become the cornerstone of 20th-century art spanned the end of the 19th and the dawn of the 20th century, and Serov was fated to be the artist who carried that transition through. It can even be said that the road travelled by Russian art in the course of twenty-five years – from the late 1880s to the early 1910s – was the road from Girl with Peaches to the Portrait of Ida Lvovna Rubinstein.

Without violating any of his teachers’ traditions, the young artist initiated a new method which was to evolve further in the work of most of the artists of his generation. On that road he was sometimes overtaken and even outstripped by others. When this happened, Serov would size up those who had forged ahead, evaluating them soberly, often sceptically. But the scepticism would pass, and he would feel obliged to take up his brush again to keep from falling behind the times. Serov did not want to stand in anyone’s way; he was deeply conscious of his duty to Russian painting, to his school, his teachers, and his pupils. He spurned the privileges usually accorded to a master. He was no master, he was a toiler; in fact, to a certain degree, he was even a pupil. It was by dint of great effort that he lived up to his role as a leader. Serov was an artist who honed his extraordinary talent on the whetstone of prodigious industry.

Serov was not alone in his search for new trends in art. His life was marked by a long-standing friendship with Mikhail Vrubel, Konstantin Korovin, Alexander Benois, and other artists from the World of Art group. With many of them he shared common creative interests. This is especially true of Vrubel, with whom the artist was closely associated in his youth.

Winter in Abramtsevo. The Church (study), 1886.

Oil on canvas, 20x15.5cm.

Pond in Abramtsevo (study), 1886.

Oil on wood, 34.5x24.5cm.

Autumn Evening. Domotkanovo, 1886.

Oil on canvas, 54x71cm.

The two studied together and collectively dreamed of steering new courses in art. Their aspirations, however, did not entirely coincide. Vrubel broke with the traditions of the Itinerants and made an abrupt and unhesitating turn in another direction – to Symbolism, to a new style of painting, thereby dooming himself to temporary isolation. Vrubel developed rapidly, changing to another manner with the resolve of a genius, a true revolutionary in art. Serov, on the other hand, proceeded cautiously, weighing every step along the difficult road ahead before finally combining the old with the new.

Konstantin Korovin was a close friend of Serov’s in the 1880s and 1890s, and at the beginning of the 20th century he became his colleague on the staff of the Moscow School of Painting, Sculpture, and Architecture. To the end of his days, though, Korovin never once stepped beyond the principles that he and Serov had evolved together. This was not the case with Serov, who outgrew these principles and went on to new discoveries.