28,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Crowood

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

By the end of Queen Victoria's reign, factories had become an inescapable part of the townscape, their chimneys dominating urban views while their labourers filled the streets, coming and going between work and home. This book is concerned with the architecture, planning and design of those factories that were part of the second wave of the industrial revolution. The book's geographical range encompasses the whole of the British Isles while its time span covers the Victorian and Edwardian eras, 1837- 1910, and the period leading up to the First World War. It also looks back to earlier buildings and gives some consideration to the interwar years and beyond, including the fate of our factory heritage in the twenty-first century. Factories, not surprisingly given their early working conditions, have had a bad press. It is sometimes forgotten that they were often the centres of thriving local communities, while their physical presence and wonderfully varied buildings enlivened our towns and cities. It is time for a new look at factory architecture. Well illustrated with 150 colour and black & white photographs.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2016

Ähnliche

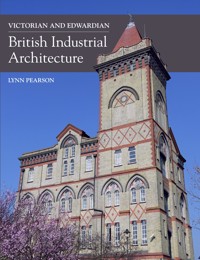

VICTORIAN AND EDWARDIAN

British Industrial Architecture

LYNN PEARSON

THE CROWOOD PRESS

First published in 2016 by

The Crowood Press Ltd

Ramsbury, Marlborough

Wiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book first published in 2016

© Dr Lynn Pearson 2016

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 78500 190 1

Frontispiece: Everard’s Printing Works, Bristol

Contents

Acknowledgements

Photography credits

Introduction

Chapter 1 Development of the Factory

Chapter 2 What Makes a Factory

Chapter 3 At the Works: Engineering

Chapter 4 Building Materials

Chapter 5 Food and Drink

Chapter 6 Textiles, Clothing and Footwear

Chapter 7 In and Around the Home

Chapter 8 Paper and Printing

Chapter 9 Victorian and Edwardian Factories Today

References

Bibliography

Index

Acknowledgements

Of the numerous people who have helped and supported the research and writing of this book, I should particularly like to thank Amber Patrick, who very kindly ran a critical eye over the text and offered welcome suggestions for its improvement. Of course, any remaining errors are entirely my own work. I should also like to thank Morag Cross for generously sharing her research on the Scottish Co-operative Wholesale Society and Shieldhall. I am most grateful to Penny Beckett, Mildred Cookson, Sue Hudson, Daphne Kemp, Gunilla and Michael Loe, Ian R. Mitchell and Margaret Perry for assistance in many and various ways. I much appreciated the help provided by the staff of the British Library, Bursledon Brickworks Industrial Museum, Frogmore Paper Mill, Gayle Mill, the Irish Linen Centre at Lisburn Museum, Laverstoke Mill, the Long Shop Museum in Leiston, Maryhill Burgh Halls, the McManus in Dundee, the Mills Archive, Stanley Mills near Perth, Strathisla Distillery, and Temple Works, Leeds.

Photography Credits

I am grateful to the following for allowing me to reproduce the images listed below:

Fig. 7 Courtesy of the Library of Congress (Photochrom Collection, LC-DIG-ppmsc-08610)

Fig. 54 © Gateshead Council

Figs. 65 and 113 © Crown copyright.HE

Fig. 109 Canmore DP 144384

Fig. 146 Historic England

All other images were photographed by the author or form part of the author’s collection.

INTRODUCTION

BY THE END OF QUEEN VICTORIA’S REIGN, factories had become an inescapable part of the townscape, their chimneys dominating urban views while their labourers filled the streets, coming and going between work and home. A hundred years or so before, the experience of such labour was rather different, as the vast majority of industrial employment was rural.1 Towards the end of the eighteenth century, in the early stages of the Industrial Revolution, mines, quarries, mills and works sprang up in largely rural surroundings. Towns and cities then grew as steam power became available and the railway network expanded; the needs of their populations and the inventiveness of manufacturers ensured that factories appeared to deliver the goods, the stuff of all sorts, that people needed and desired. Much industrial employment moved from the country to the city, where many of the new jobs were in manufacturing, although we should remember that the overall picture was complex; not all factories were large concerns, not all were in towns and cities, and many small workshops survived and prospered.2

Fig. 1 Former industrial buildings beside the river Avon in Bath. The red brick structure is Charles Bayer & Co.’s corset factory (1890 and 1895); to its left is Camden Mill (1879–80, extended 1892), a steam-powered flour mill designed by the inventive Bristol architect Henry Williams (1842–1912). Partly in view beyond is Camden Malthouse.

Fig. 2 Part of the 1913 extensions to Reeves Artists’ Colour Works (1868), an artists’ materials factory in Dalston, London; a storey was also added to the adjoining works, which now houses small businesses. Note the delicate mosaic detailing.

This book is concerned with the architecture, planning and design of those factories that were part of the second wave of the Industrial Revolution. They carried out manufacturing and processing activities rather than housing the extractive and heavy industries, transport or utilities. Our focus is on mass production, assembling and finishing in factories and works, although offices are included when they are integral parts of factory buildings, as are warehouses as they were an essential part of the distribution network. This is the architecture of making things, of consumption, an architecture that transformed our towns and cities in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries through the construction of numerous factories and works, many of them proud architectural advertisements for the processes taking place within.

Britain had become the world’s leading industrial nation through its technological innovations during the late eighteenth century, but by the time of Victoria’s accession other nations were increasingly able to compete and England could hardly be called the workshop of the world.3 However, the new factories broadened Britain’s industrial base, adding in light engineering, a wide range of processes based on organic chemicals, a huge amount of food and drink processing and manufacturing of all types. Fortunately, many of these nineteenth and early twentieth century industrial landmarks still remain as part of our townscapes today, although our stock of such factories is diminishing, along with the visual evidence of their original appearance.

The book’s geographical range encompasses the whole of the British Isles while its time span covers the Victorian and Edwardian eras, 1837–1910, and the period leading up to the First World War. We also glance back to earlier buildings and give some consideration to the interwar years and beyond, including the fate of our factory heritage in the twenty-first century. Factories, not surprisingly given their early working conditions, have had a bad press. We forget that they were often the centres of thriving local communities, while their physical presence and wonderfully varied buildings enlivened our towns and cities. It is time for a new look at factory architecture.

Chapter 1

DEVELOPMENT OF THE FACTORY

EARLY FACTORIES OR WORKS WERE OFTEN no more than small, utilitarian shed-like additions to or conversions of homes and mills, but when greater power became available towards the end of the eighteenth century, along with larger machinery, purpose-built structures were a necessity. For clarity, we should first define factories – buildings where goods are manufactured or assembled – and works, where industrial processing is carried out, involving construction or repair. These terms are often used interchangeably, but in general works are more likely to house engineering-based activities and be based around an erecting shop; this book covers both factories and works. Industrial architecture originated as an efficient, functional solution to the problem of accommodating machinery that was powered first by water and then by steam. The spatial relationship between machines and power source, together with the need for light within the building, resulted in rectangular, multi-storey blocks with long ranges of windows allowing good light penetration. By the 1780s this basic factory form, which could withstand the forces generated by machinery in use, had been developed by engineers and manufacturers.1

The Georgian Factory

Although many of the early water-powered mills were visually rather bleak, their spectacular setting besides rivers and streams in often beautiful countryside, for instance the Cotswolds, Tayside or the Derbyshire Dales, gave them an intrinsic beauty. The lack of smoking chimneys and soot-blackened buildings undoubtedly reinforced the impression that they were ornaments in the landscape, just as Georgian mansions were in their estates. As factories spread across the country, some industrialists began to give greater consideration to the appearance of their new buildings, the better to impress their peers, clients and workforce. The prevailing architectural style of the Georgian period was classical, more particularly Palladian, and this treatment could easily be applied to the factory facade.

Fig. 3 The main facade of Titus Salt’s massive Italianate alpaca wool mill (1851–53) at the heart of Saltaire, near Shipley in Yorkshire. It was designed by the Bradford architects Lockwood & Mawson, advised by the millwright and engineer William Fairbairn. Now known as Salt’s Mill, its huge floor space is devoted to cultural and retail uses.

Fig. 4 An early twentieth century postcard view of Samuel Fox & Co.’s steelworks at Stocksbridge near Sheffield. The site was first a silk mill, in the mid-eighteenth century, then a cotton mill before Fox took over in 1842. The works, which initially specialized in wire and umbrella frames, was expanded greatly during the 1860s. The little office building (1868), topped with a clock, was by architects Paull & Robinson of Manchester.

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!