11,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Oldcastle Books

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

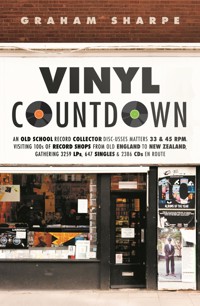

'You hold in your hand a miracle.A book about a passion, and the hipsters, oddballs and old heads who share it, written by one of their number, albeit a ludicrously erudite one' - Danny Kelly A revival of interest in vinyl music has taken place in recent years - but for many of those from the 'baby boomer' generation, it never went away. Graham Sharpe's vinyl love affair began in the 1960s and since then he has amassed over 3000 LPs and spent countless hours visiting record shops worldwide along with record fairs, car boot sales, online and real life auctions. After leaving his job at William Hill, his retirement dream was to visit every surviving secondhand record shop across the world. Whilst Graham still has a little way to go on his travels, Vinyl Countdown follows his journey to over a hundred shops across the globe including the many characters he has encountered and the adventures he accrued along the way. From Amsterdam and Angus (Scotland), to Bedfordshire and Budapest and Tennessee and Wellington (NZ), always returning to his local record shop Second Scene in Bushey to report on progress. Vinyl Countdown seeks to reawaken the often dormant desire which first promoted the gathering of records, and to confirm the belief of those who still indulge in it, that they happily belong to, and should celebrate the undervalued, misunderstood significant group of music-obsessed vinylholics, who always want - need - to buy... just one more record. Vinyl Countdown is a mesmerising blend of memoir, travel, music and social history that will appeal to anyone who vividly recalls the first LP they bought and any music fan who derives pleasure from the capacity that records have for transporting you back in time.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 638

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Ähnliche

To Julian & Helen, who run Second Scene and who not only made me welcome, tolerated my presence, answered my questions, and gave me discounts, but were happy not to demand to see in advance what I’d written about them. I thank them and really hope I’ve done them justice.

Redundancy after almost half a century spent working for the same company prompted Graham Sharpe to turn to his enduring first love to cushion the blow, sparking a unique autobiographical journey through his life via his ever-growing vinyl record collection; in the process forensically examining every aspect of record collecting; and launching him on an immersive, ongoing ambition – to visit every second-hand record shop in the land, perhaps, even, the world…

FOREWORD

by Danny Kelly (music fan, former editor of NME and Q, helpless vinyl junkie)

You hold in your hand a miracle. What other word can you use to describe a book, published two decades into the twenty-first century, about the myriad delights of vinyl records?

If, just ten years ago, you’d said that vinyl would now even still exist – never mind be the subject of widespread conversation, adoration and learned tomes – men armed with tranquiliser darts would’ve lurked outside your house, questioning your cognitive health.

All of which goes to show just what a long, strange trip the whole world of vinyl has been on.

For four decades, from the invention of the Microgroove some seventy years ago, to the coming of CDs, the plastic record (LP, single, album, 45, disc, platter, long player, shellac, EP and 100 other variants) ruled the musical roost. Records sold in uncountable numbers, became fetish objects; radiograms, stereograms, Dansettes and stereo systems competed with televisions to be the centre of household attention. Every home had records and the means to play them.

Discs became identifiers, cultural name-tags. When I was at school in the 1970s, the LP you carried under your arm – Deep Purple, Curtis Mayfield, David Bowie, King Crimson or Nick Drake – spoke of which tribe you belonged to, and broadcast a loud message of how exactly you saw your teenage self.

Records were important. Records were loved.

Then, with bewildering suddenness, it seemed over. Compact discs were the shiny harbingers of a new world of apparently perfect sound, less cumbersome playback gear and, for those with lots of music, fewer fears of catastrophic spinal damage.

Vinyl became old hat, a hissy, popping reminder of post-war austerity, the three-day week and greasy-haired youths in bell-bottoms.

People threw whole collections into skips; charity shops were swamped with Leo Sayer, ELO and Paul Young; people like me who clung on to their precious plastic were mocked in the street by local urchins, dismissed as geeks and freaks. The reign of vinyl ended, consigned to the dustbin of memory and the creaking, dusty shelves of a few diehards.

But somehow – mysteriously, incredibly – it didn’t quite die. Though record shops went bust and the gates of pressing plants were padlocked, records refused to completely depart the stage. Hip hop artists, recognising that the imperfect vinyl sound was human and warm, sampled it into their otherwise flawless digital robo-sounds. Advertising agencies used records and record players to convey an authenticity and tactility increasingly lacking from modern i-life. And music folk – fans and artists alike – began to ache for a connection with their beloved sounds that amounted to something more than a faceless file arriving in your download box. A whole technology that had been left behind was suddenly once again front and centre, gloriously ubiquitous, and hilariously hip.

I honestly can’t think of a historical precedent.

The enduring, often opaque wonders of records, record labels, record players, record shops, record cases, record shelves and record collecting do need chronicling, explaining, enjoying and celebrating. And who better to do it than a man who certainly never made the schoolboy error of offloading his Tamla Motown A-labels on to the local branch of Oxfam?

I first met Graham Sharpe when he invited me to become a judge on the William Hill Sports Book of the Year, the important literary award he’d developed with his great friend, the late John Gaustad. At first, if I’m honest, I thought he was just a sharp(!)-dressed man who worked for a bookmaker. My illusions were quickly shattered. It turned out that, sure, Graham was a smiling advocate for horse racing and betting, but also harboured ocean-deep passion for football, Luton Town, great writing of every kind and a host of other enthusiasms that most definitely included the universes of records and record collecting.

By the time I discovered that he had bought at auction the leopard-skin-design jacket of the late Screaming Lord Sutch, I knew for certain that this was a man with whom I could do business.

In the intervening quarter of a century, Graham and I have become firm friends. In between a full-time job and a busy career as an author – I talk about writing books, he gets on and does it – he continued, and still does in semi-retirement, to buy, collect, treasure and talk about music on physical, grooved, formats. His understanding of the quirks and foibles of collectors – a mixture of possessiveness, weird gallery curation, completism, lonely late-night filing and hopeless addiction – means that I can talk to him about my own out-of-control hoarding without fear of being embarrassed or judged.

Indeed, when I recently revealed to him that I was wasting my life savings on renovating a vast old rustic cowhouse to shelter my sprawling array of vinyl (sub-categories include Poetry 45s, Unlistenable Modern Classical, and Advertising flexi-discs) he just beamed broadly. ‘Can’t wait to see it,’ he said.

You hold in your hand a miracle. A book about a passion, and the hipsters, oddballs and old heads who share it, written by one of their number, albeit a ludicrously erudite one. I’ve no doubt that once read, it will take its place on those groaning shelves, proudly sandwiched between the gatefold sleeves, coloured vinyls, lead-heavy box sets and multiple copies of ‘Forever Changes’.

It deserves to.

Summer 2019

INTRODUCTION

IN WHICH THE AUTHOR ADMITS TO VINYL ADDICTION AND EXPLAINS HOW IT HAS IMPACTED ON HIS LIFE

‘Vinyl’s making a comeback, isn’t it?’

The man in the record section of the charity shop was making friendly conversation as he spotted me looking through the discs.

I looked up and regarded him, perhaps a little too sternly, before responding, perhaps a little too aggressively:

‘It never went away.’

I believe that anyone who owns two or more records is self-evidently a record collector.

Whenever you add another one to however many you already have you are enhancing that collection.

I have thousands of the things, and despite the incomprehension of my Mum who, when asked to make my Christmas present an LP one year, replied, ‘Why? You’ve got records already’, I continue to add to the total regularly.

This book deals with every aspect of record collecting I could think of. How it’s done, when it’s done, where it’s done, why it’s done, who does it and how one goes about it.

Read this book – with its tales of countless hours spent in 100s of record shops worldwide, at record fairs, car boot sales, online and real-life auctions, romances consummated in vinyl, fruitless searches for elusive records, selling, buying, exchanging, coveting, losing, loving, hoarding, hating, finding, wanting, demanding records – and you may just begin to comprehend the emotions involved in a lifelong vinyl love affair.

If you used to be a collector but believe you aren’t one now, think again. Get the record player out of the loft, gently caress the dust off the first disc to come to hand, and give it a spin. You’ll wonder why you ever stopped doing it. If you don’t, you’ve lost forever what would once have been one of your simplest, but greatest, pleasures – playing favourite records.

If you, your grandparents, Mum, Dad, brother, sister, aunty, uncle, friends, or workmates have ever shown an interest in, and/or collected, records, 33 and 45 rpm circular (usually, not always) vinyl discs, this book – my vinylography, although the publishing poohbahs wouldn’t let me call it that! – should prove a real treat for you or them.

Records have a greater capacity than Doctor Who’s Tardis for transporting you back in time. Even someone as ‘woke’ and on trend as the highly influential writer for The Times Caitlin Moran acknowledged as much when, in April 2019, she explained how records encapsulate ‘everything you were before’ and should therefore be revisited and revered, otherwise ‘you’re selling out the only person who has believed in you… : you.’

This book seeks to reawaken the often dormant desire which first promoted the gathering of records, and to confirm the belief of those who still indulge in it, that they happily belong to, and should celebrate the undervalued, misunderstood, significant group of music-obsessed vinylholics, who always want – need – to buy… just one more record.

1

IN WHICH… I COUNT MY BLESSINGS

When, aged eleven, I acquired my first single, American string-plucker Duane Eddy’s 1962 Top 10 hit, ‘(Dance With The) Guitar Man’, I had no thoughts whatsoever of creating a record collection.

But it wasn’t that long before the single – which hangs above my desk even as I type these words – was joined by my first long player. Which, it turns out, despite my belief when I began writing this book, was NOT the Rolling Stones’ debut, as I’ve been telling anyone interested for many years, but The Beatles’ Please, Please Me.

Odd how time can turn the truth – or the version of it you have adopted – on its head.

I can now be so sure, because I went through all of my Stones and Beatles’ LPs, and there on the back cover of my mono copy of 1963’s Please, Please Me (seemingly a fourth pressing, according to the Rare Record Price Guide 2020, and thus worth £150 if only it were remotely close to being in mint condition), written in a combination of black felt tip, blue and red biro are the following markings:

G.S. (1) G Sharpe. 20 Borrowdale Avenue, Wealdstone, Middx. HARrow 0257.

The (1) was clearly superfluous. At this point I owned just this LP.

The Beatles’ LP was soon joined by Number (2), the Rolling Stones’ eponymous April 1964 debut. Mine is, I believe, the second pressing with the 4.06 minute ‘Tell Me’ and listing ‘I Need You Baby’. (Which gets it a £200 rating, with the same caveat). It, too, boasts my initials – together with red biro ‘real writing’ signature, address and telephone number.

These two records demonstrate starkly the differences between The Beatles and the Stones in those days, when your street cred could depend on which of the two you were aligned with.

To refresh my memory, I decided to listen to, and look closely at, both albums, one after the other. I wouldn’t have done that since 1964.

Please, Please Me was released on 22 March 1963. I’m not sure when I managed to get a copy but it won’t have been long after release. I was 12 years old. The Stones’ LP, The Rolling Stones, was not released until 16 April 1964.

The first obvious difference between the two is that The Beatles’ album has its title on the front cover, the Stones’ on the back. The Beatles are smiling at their prospective buyers, the Stones gazing stern-faced at their potential audience. The Beatles offered 14 tracks for the money, the Stones a dozen.

I want to mention at this point how vital covers are to LPs. The number of records I’ve bought on spec, purely as a result of deciding the cover photograph or image suggests the musical content will meet with my approval, is astonishing. Occasionally it can mislead you, although, when it does, it is usually because the record company wanted to ‘suggest’ that the contents would be something they actually never were.

A poor cover can ruin any chance the record contained within it ever had of reaching its true potential. Check out Harsh Reality’s sought-after, £500-valued 1969 schlocky, gory, awash with fake blood Heaven & Hell cover. (‘Blighted by one of the most inappropriate sleeve designs of its day’ wrote John Reed in notes to a 2011 reissue.) It was designed by one Phil Duffy, but would have sold more with a better sleeve which didn’t shout ‘trying too hard’, although (ironically) it would now be worth less.

But a great sleeve design can enhance an average record to the point where its impact exceeds its quality – witness Quintessence’s 1970 eponymous £80 album cover’s inspired, innovative, eye-catching central door-style opening. To my ears the music came nowhere near matching the cover’s impact.

The music on The Beatles and Stones’ records highlighted differences between the groups’ images. The Beatles were far more approachable, with eight self-penned tracks, all pretty much love-based, very catchy and almost sing-along, definitely ultra-commercial. The other tracks included middle-of-the-road fare by Goffin-King, and Bacharach-David-Williams. ‘Twist And Shout’ was the grittiest track, which had recently been a hit for the Isley Brothers, while ‘Anna (Go To Him)’ was by bluesy soul singer Arthur Alexander – from whom the Stones would shortly afterwards borrow and improve ‘You Better Move On’.

Paul and John shared lead vocal honours, but The Beatles showed a little group democracy by chucking ‘Boys’ to Ringo, and letting George lead the way on ‘Do You Want to Know a Secret’ a question markless song which Billy J Kramer would later take into the Top 10.

There was no question (and never has been) of Mick Jagger letting the rest of his group muscle in on his lead vocals, and he fronted 11 of the 12 tracks on the Stones’ album; the other, ‘Now I’ve Got a Witness (Like Uncle Phil and Uncle Gene)’ was an instrumental on which Gene Pitney played piano. Uncle Phil was a reference to Phil Spector, who co-wrote ‘Little by Little’ with the writer(s) of ‘Now I’ve Got a Witness’ – Nanker Phelge. ‘Nanker Phelge’, with occasional minor variations, was a collective pseudonym used in their early years as a catch-all songwriting name for several group compositions.

Explained bass player, Bill Wyman in his 2002 book, Rolling with the Stones:

‘When the Stones cut “Stoned” – or “Stones”, according to early misprinted pressings – as the B-side to their second single, 1963’s “I Wanna Be Your Man”, Brian (Jones) suggested crediting it to Nanker/Phelge.’

The entire band would share writing royalties. ‘Phelge’ came from Edith Grove flatmate Jimmy Phelge, while a ‘Nanker’ was a revolting face that band members, Brian in particular, would pull. The ‘sixth Stone’, Ian Stewart, who played keyboards on four of the debut album tracks was also included. Only one track was credited to Jagger-Richard – ‘Tell Me (You’re Coming Back)’. At this stage Keith was still Richard, rather than Richards. None of the Stones’ LP tracks was issued as a single.

This is a harder-edged album than Please, Please Me. There is far more R’n’B and blues than pop influence on the tracks. Andrew Loog Oldham’s sleeve notes justly describe it as ‘a raw, exciting basic approach’ while, in his Please, Please Me sleeve notes, Tony Barrow oddly describes the music as ‘wild, pungent, hard-hitting, uninhibited’ – a description not entirely justified by the tracks on offer.

Very different albums, very different groups and images – but both appealed to most of the same audience as a whole, as they were both so vibrant, young, and refreshingly different. Most of those listening had never heard such music before. But even at this stage, the ‘safer’ option to side with was The Beatles. If you wanted ‘edge’ you lined up behind the Stones. Both groups were pinching styles from older soul and blues artistes, adopting, adapting, sometimes blatantly stealing, yet it was all new to the majority of my baby-boomer teenage generation.

Money was tight for me as a young, still-at-school teenager, whose weekly pocket money was about half a crown. My LP Number (3) was, slightly oddly, Out Of Our Heads, from 1965, by the Stones – their third LP – and not, by the look of it, a new copy. I clearly hadn’t been able to afford a copy of their second outing; (4) was also second-hand, Aftermath, from 1966, the Stones again, while (5) was the 1965 Hang On Sloopy LP by US pop group, The McCoys, whose British fan club I would eventually end up co-organising.

Although I was clearly a Stones’ man, I had to wait to acquire 1965’s Rolling Stones No 2 – it was my Number 26 LP. Their Between the Buttons from 1967 was my Number 7, and the same year’s Their Satanic Majesties Request Number 9.

My ‘new’ records were coinciding with birthdays and Christmases, the second-hand ones indicating that I was now seeking out record shops selling such things. It was some while before I began to lose count of how many I had, but during the late 1960s that happened, as I began to store them all over my bedroom, in cupboards, on shelves and under the bed. It would be over 50 years before I could again say with certainty how many LPs were in my collection. I counted them specifically for this chapter.

This wasn’t a straightforward undertaking.

In the front room there were two cupboards-worth, plus one bookcase shelf full of LPs, half a dozen shelves containing runs of between 50 and 100. Oh, along with the two sets of Beatles and Stones records standing on the floor. Then I moved into my study area in the hall to count how many albums there were on the middle shelf to the right of my laptop. After they’d been added up, I moved to the wardrobes in the main bedroom, where there are a couple of hundred. Then there is the ‘library’ room where my horse racing and gambling books live alongside quite a few albums – several hundred here, in fact. Up the steep, alternate step staircase to the top room – which now holds the largest segment of the record collection. These used to live in the room immediately below – number two son’s bedroom which was, though, adversely affected when a leak enabled an ingress of water, responsible for the Great Cover Disaster of 2017.

As a result of this I now own more records with water-damaged covers than, frankly, I would have liked. Some of them very collectable items indeed. Amongst them, Little Free Rock (£175); Audience’s Friend’s Friend (£100); May Blitz (£400); Quintessence (£80); Bowie’s Hunky Dory (£50); and McDonald and Giles (£150).

This should make me feel angry and upset every time I see them. But, just as when I look at the sun-damaged, football-wrecked, alcohol-bloated, overwork-battered bodies of my now ageing friends of many years standing, it only makes me fonder of them to think of what we have gone through together, and despite all of this managed somehow to remain standing, albeit unsteadily.

My insurance company did shell out to enable me to replace the damp discs – well, with reissues. They even sent the covers off to a specialist company who endeavoured to bring them back from their watery grave. A valiant, but largely ineffectual, exercise.

Fortunately, water does not have an adverse effect on vinyl, so the only obvious evidence of their ordeal is in the condition of the covers which have concertinaed up, but remain obviously what they are.

I have no desire to chuck them out and bring in equally ancient copies with different marks of longevity about which I know nothing, or to replace them with prettier, younger yet not quite the same ‘reissues’. They are now uniquely ‘storied’ and I very much doubt that I would ever have parted with them anyway. Well, maybe Quintessence.

After five days of counting – a very frustrating undertaking as slippery plastic covers make it too easy to count three as two or vice versa – which wears down the will to live, and inflicts numerous small, but painful plastic- or paper-cuts, I completed the task.

I can tell you that as of 10.43am on Tuesday 27 June 2018, having earlier reached the 3000 mark by counting the Robert Cray Band’s Too Many Cooks, I was the proud(ish) owner of 3239 LPs – give or take a few. The last one counted was The Herd’s Paradise Lost (£70 if in good nick, which this one definitely isn’t). Technically this belongs to my wife, but on the basis of what’s mine is hers and what’s hers is hers, I’m including it. That’s probably 10 per cent more than I’d reckoned on, and a little down from the peak amount, given that I had recently been selling a few off, albeit also gathering more in, but please don’t tell Sheila that…

Really, who NEEDS over 3200 LPs? No one, if I’m honest.

Probably closer to 3500 by the time you read this. After all, I brought back two dozen from my last trip to the Antipodes in 2019 alone. Then there was the June 2019 San Francisco haul… I can thoroughly recommend Haight Ashbury’s Amoeba Records for its selection, its prices – and its bulldog clip system of enabling you to leave your bags at the counter.

It also contained many examples of my own vinyl catnip which explains why I persist in buying and listening to music from my formative years: records made in the late 1960s/early 1970s, by groups of similar age and thoughts to me, but which made no impact, weren’t played, publicised and popularised at the time, but were written for people like me and sound as fresh and exciting as the day they were recorded. Rediscovered and reissued by specialist labels, they are what I seek out.

I could spend five hours daily playing a completely different set of nine LPs for an entire year. And at the end of that year I’d still have played every record I own just once.

Do I collect to impress people by telling them how many records I own? That is quite possible, but if so, it doesn’t work. A look of uncomprehending pity is the default reaction should I admit this shaming statistic to someone. The next reaction, one word: ‘Why?’

I do it largely to impress myself, for sure, but that’s pretty pointless, isn’t it? Am I going to tell myself I’m NOT impressed?

I do it because I want to do it.

I do it because I CAN do it and because when I first started wanting to accumulate records I couldn’t really afford to do it without sacrificing some other, more essential purpose to which the money could be put.

I was thoughtful enough on my own and, soon, my wife’s account, when I was contemplating buying a dozen LPs at the Sellanby second-hand shop during the 1970s and 1980s, always to choose the cheapest version they had available – that was my idea of compromising and saving money, thus allowing us to pay the mortgage. Which does at least indicate that I wasn’t over-concerned with sell-on values.

I do believe collectors are divided into those who long for pristine, blemish-free, silent-background record reproduction and those who, like me, enjoy (indeed, possibly prefer) hearing the accumulated scratches earned during the long, active life of a second-hand disc bought frugally.

Having totted up the LPs, I was now wondering how many CDs I owned, so started to count them as well. I took a breather on reaching 1000. I counted double albums as one in the vinyl tot-up, likewise with the CDs. Box(ed)-sets I’ll call just one.

The CD count did not take as long as the vinyl, mainly because I wasn’t going to let it, so I may have slightly rushed. I’m confident the final total was, er, getting on for 2500. Ish. Thus, as well as playing nine different LPs every day for a year I could also play six different CDs without, etc…

I’ve also just realised that I left the 60-plus CDs by Free, Paul Rodgers, (Small) Faces, Bad Company, Bon Jovi, AC/DC, Humble Pie, The Killers, etc designated as Sheila’s, but which I bought for her, off the list. Because they’re stashed on a shelf in the kitchen – not my territory.

Are these excessive quantities?

A Facebook post from collector, Mark Turner, asked members of the vinyl group to which we belong:

‘How many records are enough?’

Before trying to answer this question, perhaps we should consider Rutherford Chang. The last time I checked, Rutherford Chang owned 2435 numbered copies of ONE RECORD alone – The Beatles’ White Album. Not content with that, he is constantly seeking more. His collection has been displayed at KMAC Museum, Louisville, Kentucky. ‘Each individual album is posted @webuywhitealbums. If you have a copy in any condition please let me know: [email protected]’ he pleads.

Mark Turner’s ‘How many?’ query prompted a deluge of responses, including mine: ‘To many of us there is no such number.’

By and large responders agreed:

‘When your wife/husband says “anymore and you sleep in the garden”.’

‘Just one more…’

‘The Limit does not exist.’

‘11,672.’

‘One more than I already have.’

‘The one you buy tomorrow will be enough.’

‘When you can’t remember how many you already have.’

‘I’ll let you know when I get there – 12,000 and counting.’ (Designer Wayne Hemingway MBE recently boasted: ‘I have more than 13,000 vinyl records.’)

I empathise with all of these sentiments, but let me now tell you how and why I came up with the idea for this book…

2

IN WHICH… I REVEAL HOW THIS BOOK WAS BORN

Because I was born in 1950, and am therefore of a certain vintage, collecting music by downloading or streaming just does not appeal to me. I want something to own, to hold, to look at – even better, something to read – while I’m listening, to give me a certain connection with the artist(e)s who originally created it. I’m happy to pay to do so. To tread this path, I can either choose to hunt for records online, or visit the constantly fluctuating number of shops selling only second-hand music.

There are also increasing numbers of shops which stock only new vinyl, albeit often containing reissues of previously issued music, or vintage sounds not deemed worthy of issue at the time.

New shops are appearing regularly, many of them combining food and drink facilities with records for sale. Some established shops are closing, for various reasons, perhaps because the owner has not taken notice of the old but established adage, ‘give them what they want and they will come’, or because (s)he has chosen the wrong location.

After I was made redundant, I realised I needed something to occupy my time. The idea of managing to take a look at the many record shops I was aware of, but had never yet visited, due to time constraints, loomed large.

I pitched a feature idea to one of the magazines to which I have subscribed for years: Record Collector, launched in 1979, and now the UK’s longest-running music magazine. I hoped they might not be able to resist a story about someone setting out to visit every one of the 90+ record shops in England selling second-hand vinyl which currently advertise in their mag. The article was duly commissioned and printed across two pages in October 2017.

I was pretty sure that it would immediately produce a barrage of complaints from readers that they had already visited all the shops and that my ‘mad quest’ as Ian McCann, then RC Editor had dubbed it, had been done before. It didn’t. It appeared that, if I could indeed create and complete this journey of, sorry, disc-overy, I might even have a valid claim for an entry in the Guinness Book of World Records.

The feature was illustrated by a photograph of me standing outside Second Scene, my local record shop in Bushey, near Watford, run by Julian and Helen Smith, who have become friends over the past few years, and from whom you will be hearing in this book on a number of occasions.

There it was in print. I’d pledged to visit almost 100 record shops. That meant I would now actually have to set about doing it. Fortunately, I hadn’t been rash enough to set a time-limit and had realised, too, that on its own, such an idea wouldn’t sustain a full book, involving too many, too similar chapters. Instead, the idea was growing of combining multiple record shop stories with stories about every other aspect of record collecting.

I started to travel around the country – the world – somewhat randomly, ticking off shops as I went. I began to enjoy the experience of visiting new places, taking in the local record shops of Australia’s Blue Mountains, Salisbury, Liverpool and Stockton on Tees; San Francisco, Oxford and Cambridge; Harrow and Hereford; Oslo, Guernsey and Jersey; New Zealand, Norf and Sarf London. Always returning to Second Scene to report on my progress.

I decided that, unless a conversation began naturally between us, I would not go out of my way to instigate verbal contact with record shop staff, other than Julian, as I wouldn’t want them to clam up if I mentioned I was writing a book, or begin bigging themselves and/or their shops up to me.

It is amazing what you might hear if you just listen. Vinyl Revelations is located at 59 Cheapside, Luton, along with the message: ‘We do not have a letterbox so please do not use this address for postal correspondence!’.

The almost inevitable middle-aged proprietor is telling a customer, ‘I’ve been in the record business for twenty-four years. I’ve seen the ups and downs.’

The customer wanted to sell him two records: ‘I’d like a tenner for each.’

‘But I already have copies of both that I’m selling for four quid a throw.’

‘Well, how about a tenner for the two?’

Fortunately, it didn’t take long to find a publisher as keen on the book idea as I was, and as I travelled around, talking to knowledgeable, obsessive record collectors, phlegmatic record dealers, depressed record shop owners, optimistic online vinyl traders, I soon appreciated just how deeply ingrained the love of, and for, records and record shops has become over the years.

Virtually everyone to whom I mentioned the book idea was able to recite with very little prompting the names of the first record they had bought and the shop they had bought it from. Even though they may not have played or bought vinyl for many years they smiled at the memory of first hearing those amazing, new sounds on tinny, usually tiny, transistor radios. And at the way in which they then felt compelled to dash out to buy their own copies, enjoying the follow-up chat at school or work they created.

Reminded about that experience, most of them then said they still had that and many other discs stashed upstairs in the loft. They kept meaning to get them down to listen to them again on the vintage record player that was stored there as well. This had allowed them to stack up half a dozen singles which would, one by one, plop down satisfyingly on to the one which had just been played – albeit by that action they were leaving scratches and other marks which inevitably affected their sell-on value adversely.

But who then suspected there might ever be such a bonus for the far-seeing collector?

Back then, everyone owned, or had access to, a record player. Even the greatest sportsman to tread this planet – Muhammad Ali.

I met Ali’s biographer, Jonathan Eig, when he came to London, having been shortlisted for the prestigious William Hill Sports Book of the Year award in 2017. He told me that he owns Ali’s record player:

‘I found a listing for Muhammad Ali’s record player. The seller claimed to be the son of one of Ali’s early lawyers. The opening bid was $250. No one had bid. Figured it wasn’t really Ali’s record player. I bid anyway. I was ready to send the money, but the seller emailed me and said he was bringing it to Chicago. Definitely has to be a scam, right? Figured I’ll never get the record player. Then I got a call. He was in Chicago, and wanted to meet. He pulled up in a huge van. He was a big guy – 6ʹ5ʺ, 280lbs. He opened the trunk and showed me the record player. His name was Frank Sadlo. Frank knew Ali for years. He helped clean out the house after Ali’s mother died. That’s how he got the record player. Frank’s dad was a white lawyer working in the poor black neighborhoods of Louisville in the 1940s and 1950s. He represented Cassius Clay, Sr. and wrote the first professional contract for Muhammad Ali.’

How cool is that, owning Ali’s record player!? I do, at least, own a copy of his 1963 LP, I Am the Greatest.

The mechanics by which 1960s record players allowed discs to drop one by one could be altered to play the same record over and over, particularly when it was relevant to a recently terminated teenage love affair.

I recall listening to the Kinks’ ‘Tired of Waiting for You’ sixteen times in succession, in frustration that my then girlfriend, Pauline, from a few doors down the road, appeared to be far more interested in taking the bus to Heathrow Airport in the hope of seeing the Walker Brothers fly in or out than in walking up the road to see me.

The Kinks had already become important to me. The life-changing, instant impact of hearing the opening bars of ‘You Really Got Me’ absolutely charging out of the one tinny speaker of our black and white telly in the summer of 1964! I can’t remember whether the record was being played on Juke Box Jury, or the group was featured on Ready, Steady, Go, but I was left virtually paralysed as the record roared out – and into my heart forever. WHAT a sound. WHAT a riff. Whoever played it. I was thirteen and a half. Of course, I had to have that record, and rushed out to buy it at the first opportunity.

So influential to me were the Kinks that I would have laughed at the very idea of any group ever pretending to be them, and actually becoming successful by charging people to watch them not quite be the Kinks. But this phenomenon would emerge. I put it down to baby-boomers wanting to recapture their halcyon days…

3

IN WHICH… JACK WHITE DENIED VINYL WAS DEAD

Kevin Godley, of prolific vinyl hit-makers, 10cc, told Mojo magazine in January 2018, ‘I have a soft spot for vinyl. It reminds me of when music was rare, significant and a work of art…’

He was born in 1945, five years before me, and like most of my contemporaries, grew up with records and music always close at hand and ear. This attitude towards records was the prevailing one for many years – Jack White of The White Stripes, born almost exactly 30 years after Godley, inherited it and defends it to this day, recalling how:

‘I remember in 1999, and 2000, The White Stripes asking television hosts if they could hold up the vinyl record instead of the CD. And at that time they were like, “Why would we do that?” That’s how dead vinyl was.’

Unlike today, of course, there were relatively few competing personal entertainment options in earlier days, and hit records would sell hundreds of thousands, or even millions, of copies. Most of those who bought, or were given these records were, as I was, entirely devoid of any musical talent whatever. I may have had a toot on a recorder as a kid but displayed zero ability and have genuinely never even strummed an electric guitar to this day, other than in an air-guitar way. Yet music has dominated much of my life. But then there are people obsessed by football, golf or horse racing who can’t kick a ball straight or hole a putt from six inches and have never sat on a horse.

Initially, popular, or ‘pop’ records released in the late 1950s and early 1960s were likely to have been heard by eager, young, potential consumers on non-BBC, usually foreign, radio stations like Radio Luxembourg and American Forces Network.

Rock ‘n’ roll music was leading the way then. Guided by usually financially motivated managers and agents (okay, some things never change), Elvis Presley, Chuck Berry, Fats Domino, the Everly Brothers and many others first embraced, then pop-ified rock ‘n’ roll’s harsher elements, which emanated from the States, with their roots in the blues.

Their influence quickly spread across the water, but was then somewhat emasculated in Britain when Cliff Richard, Marty Wilde, Billy Fury, Adam Faith, Tommy Steele et al began to move from their imitative, wannabe Yank teen-idol phases, towards a more middle-of-the-road, commercially attractive, yet blander, sound.

Then, though, The Beatles arrived to stop in their tracks the careers of those who had thought they had the mainstream music scene sewn up, and to spark the whole 1960s explosion of pop, psychedelia, rock music and so much more, leading on to prog(ressive) rock, punk, heavy metal and many other hybrid styles of music.

Soul and ska music also became important, particularly to those youngsters who loved to dance. Stax, Tamla Motown and Trojan became go-to labels for those attending and DJ-ing at discos.

In 1964, the massively influential commercial ‘pirate’ radio stations arrived – amongst them Radios Caroline, London, and Sutch. Music was avidly consumed by those of a certain age – mine – almost by osmosis, and a huge proportion of those so affected wanted to own that music for themselves, so that they could play it whenever they wanted, rather than having to wait for it to be played on the radio.

BBC Radio continued broadcasting what was described as ‘light’ music to an indifferent British audience, until 1967 when, under pressure from the ‘pirates’, it launched Radio One, but, as the name suggested, it was largely inoffensive, repetitive, chart-based bland fare, unlikely to appeal to the more musically adventurous.

Nearly everyone of my acquaintance in the mid-1960s soon owned, or had access to, a portable or transistor radio, a record player (often a ‘radiogram’) and/or a portable cassette recorder/player.

Discs, as the presenters invariably called them, spun on the programmes hosted by popular disc jockeys, would enter the collective consciousness by being bought or recorded, then played almost continuously. Some programmes, usually going out late in the day or overnight, became a cult listen for those seeking to dig deeper into the sounds available. Leading the way in this respect was John Peel.

Ageing baby-boomers may today struggle to recall their own names as advancing years take their toll, but will almost invariably still be able to remember the first record bought for, or by, them. It would usually be a 45 rpm single. ‘The 7ʺ single, as an entity is an absolutely powerful, possibly other-worldly object’, guitarist Johnny Marr would perceptively observe.

Singles were really, more accurately, doubles, containing at least two songs – or tracks – one on either side. Although to my schoolfriend, John Maule, they really were singles. Every time he bought one from our local record shop, Carnes in Wealdstone, and brought it home, he’d take it out of its sleeve, play it, then throw it across the room to join the growing pile on the other side. Why? Because, as he told me at the time, ‘There’s never anything any good on the B-side.’

How wrong I felt he was – then, and particularly now – both in his dismissal of the ‘other’ side, and in his cavalier treatment of his vulnerable vinyl. I’m certainly not alone in believing that. In his introduction to his biography, Bowie, Paul Morley writes of how the first singles he bought were ‘carefully chosen and cared for like nothing else in my life’.

My fellow baby-boomers also retain fond memories of the (often small, usually local and frequently independent) shops where they lost their vinyl virginity. Yes, there were places like Woolworths and Boots, as well as department stores, that sold them, but it was much more interesting to build a relationship with the local independent outlet and the person there who would generally be knowledgeable about forthcoming releases and records similar to the one(s) you were about to buy, but which you may never have heard of. They’d tell you what new discs would be appearing shortly and, if there was likely to be high demand, reserve you a copy.

Another of my friends and contemporaries, Martin Wilson, also challenged John’s B-side disdain, when he told me: ‘I invariably played the B-side first – I already knew what the A-side sounded like, but who knew what treasure might be lurking underneath when you flipped it over?’

John, later a ‘£10 Pom’, and I met up for a reunion in New Zealand in 2018. I’d brought with me a late Christmas present for him, which he hastily unwrapped – duly discovering that I was returning to him several of the singles he’d given to me when he fled the country half a century earlier.

Those from better-off families or with well-paying Saturday jobs (something else which my generation experienced almost universally, but which now appears to be heading towards obsolescence) may have bought, or been given LPs. Even John Maule didn’t hurl these pricey behemoths across the room. But he did manage to scratch them, if not in the way that club DJs later started to do, either. So, by the time he moved to the other side of the world allowing me to inherit most of his badly wounded records, few of them remained playable.

One of them that did, was the Small Faces’ LP, Ogdens’ Nut Gone Flake, the ground-breaking psychedelic record Steve Marriott, Ronnie Lane and company created with the help of the gloriously word-mangling comedian, Stanley Unwin. The latter’s crazily hilarious interventions between tracks helped it become one of the iconic records of the period, thus ensuring that the value of a copy in decent condition soared consistently over the years. It also boasted a unique-at-the-time round cover.

For reasons best known to himself – surely he didn’t fancy her? – John had handed his little-played copy of this LP to my sister, Lesley, who resisted every attempt I made, once I learned that she had it, to acquire it from her. Eventually, and only as recently as 2017, I had to shell out a substantial, three-figure sum to do so. Sisterly love, huh…

This raises a question. When did records, initially regarded as disposable items with little intrinsic value, begin to acquire a serious financial worth, which would appreciate with time?

Once records became established as a teenage essential of the 1960s and 1970s, shrewd entrepreneurs spotted a gap in the market. They began to offer the opportunity for those with too many records, or ones which they had grown bored with, to part with them for a modest fee. Whereupon the profit-savvy purchaser could sell them on, a little more expensively, to buyers who did not already have, and wanted to acquire them, but without having to pay the full cost of a brand spanking new version. Thus did the second-hand record market first appear, and rapidly grow, helping committed but impecunious vinyl addicts remain active.

In the States, a gentleman called Jerry Osborne began producing guides to the values of popular records from 1976 onwards. A Facebook acquaintance told me that ‘in 1978 I purchased a book titled The Record Collector’s Guide by O’Sullivan & Woodside.’ A year later, Record Collector magazine appeared.

Suddenly records had a calculable worth. This wasn’t, though, why I was already collecting. I just loved LPs and singles, and the life-enhancing qualities of recorded music, and wanted as many of them as my meagre disposable income would permit.

Today, the collecting world is divided into those who collect for the love of music, and those who collect to profit from collecting, the latter group described by Record Collector editor, Paul Lester as ‘Machiavellian high-end dealers for whom vinyl is a semi-abstract commodity much like stocks and shares.’

Most people’s vinyl love affairs dwindled as real-life responsibilities took over from their party-central teenage years. I was amongst a select few, like-minded, stubborn vinylholics, who continued to acquire, purchase, cadge, borrow, review, and occasionally sell records, for nearly 60 years after Duane Eddy first came to my attention, persisting long after the novelty had worn off amongst most of my friends, most of whom stopped buying records completely once they embarked on permanent relationships.

Music dropped off their radar, probably until their children had grown up, at which point they slowly began to realise that some of the groups whose records they had liked and bought all those years ago were still around and touring. Perhaps they were coming to a local theatre, albeit with some new, some deceased and increasingly few original members – like the ‘Herman’s Hermits’ I saw once, with no Herman (aka Peter Noone), and then again, even later, when only the original drummer remained, who still had the cheek to claim all the credit for the ‘30 million records we’ve sold’.

But as other groups packed it in, fell out with each other, retired and died off they created a gap in the market – soon filled by bands such as the Small Fakers, who replicate the original performances of Steve Marriott, Ronnie Lane, Kenney Jones and Ian McLagan; the Bootleg Beatles and Rollin’ Stoned, who do likewise, resuscitating a heavenly John Lennon, George Harrison and Brian Jones along the way. Obviously, even though these guys quite probably play the original songs more enthusiastically than the ageing ‘real thing’ could do today, they make no claims to being anything other than a pastiche of the band itself.

What does that make a group like the Kast Off Kinks? They play all of the Kinks’ great hits, and initially included two long-serving members of the band in their number, drummer Mick Avory and bassist John Dalton, while another former ‘proper’ Kink, the late Pete Quaife, used to turn up for occasional shows. But they had no one called Davies in the line-up. All the great songs were written by Ray Davies, and brother Dave contributed the slashing guitar riffs to those songs. The KOK clearly had almost no genuine claim to be the original ‘group’.

The current Dr Feelgood, who legally own that name, and who all joined the band as it progressed, while the originals dropped out, or died, contain no original members whatsoever. (In passing, my sister recently told me she had bought tickets to see Dr Feelgood. I told her I was surprised as she was not a ‘rock chick’. ‘No,’ she said. ‘To be truthful, I thought I was booking for Dr Hook!’) So are Dr F the real thing or imposters? Legally the former; morally, perhaps, the latter.

The Drifters, formed in 1953, and a wonderful original band, perhaps set the trend for groups to change over time, effectively becoming brands, with the music taking priority over the individuals in the group. The latest list of one-time members of the group shows 65 different names – including one familiar to baby-boomers – the late Doc Green!

If you delve far enough back into the 1960s there was a phase when anyone attending a gig by, for example, Fleetwood Mac, Moby Grape, The Zombies, might wonder why the band members did not look familiar. It was because rogue promoters were duping concert-goers by deliberately sending out ersatz, fake groups which, unlike today’s tribute acts, were actually pretending to be the real thing.

A conscientious tribute band will have worked very hard to ensure that their sound is almost a precise match, note by note for the original version to which they are paying tribute. When Sunday Express editor, Martin Townsend went to see the Small Fakers in autumn 2017, he was so impressed that he declared their versions of the hits ‘so good they made the hairs on the back of my neck stand up.’ I’ve seen the Small Fakers several times and also rate them highly.

But in 2018 the Fakers marked the 50th anniversary of the band they celebrate, by playing their psychedelic masterpiece, Ogdens’ Nut Gone Flake. My local venue, ‘Tropic’ in Ruislip, was packed, so much so that it was difficult to find somewhere to sit. The band announced that Ogdens’ would take up the first section of their performance, and that they would then take a break, returning with a ‘greatest hits’ set. I was particularly looking forward to Ogdens’, and the audience pressed forward eagerly. Gradually, though, the crowd eased as people nipped to the bar, to the toilets, for a fag, realising they didn’t recognise much of this material. As the group moved on to the LP’s surreal second half, interspersed with (to me!) hilarious vocal interventions as contributed by the late, great Stanley Unwin to the fore, the crowd thinned even more – many sat down to chat with friends. But when the hits began the crowd thickened, surged forward and danced with delight. I went home.

The truth is that people who support tribute bands tend to be those who might have bought the original band’s Top 10 singles and ‘greatest hits’ records, but who rarely, if ever, delved into the material they produced outside of these iconic songs. Nothing wrong with that, of course, but probably depressing for the originals, let alone the tributes, when they feel the need to stretch out a little from their tried, trusted and adored golden oldies only to be firmly steered back to familiar, safe territory by the lack of audience appreciation.

To give additional support to the originators of great music worth paying tribute to, I must add that, much though I have enjoyed watching The Counterfeit Stones, Rollin’ Stoned, The Bootleg Beatles, Like The Beatles, Small Fakers, AC/DC UK, Counterfeit Quo, Kast Off Kinks, Absolute Bowie, Roxy Magic, Fleetwood Bac, and the brilliantly named Creedence Clearwater Revival Revival, I have never bought a record by any of these acts.

Many of my contemporaries are astonished that anyone should have retained a love of the original music of their youth into their dotage. They are happy to recall and relive it on occasional nights out, but seem neither to notice nor care that it isn’t as it was, because to them that’s all it ever was – background sound accompaniment to their way of life at the time. But there are still surprisingly many early enthusiasts who have stayed the course and are proudly flying the vinyl banner. Facebook group, Vinyl Hoarders United boasted 24,865 members when I last checked. The site offers the ‘opportunity to share pictures and information of your vinyl collections, ones you want to hunt down, or any interesting vinyl you think the rest of the members should know about.’ Vinyl Records Forever, had attracted 13,449 members, Vinyl Records For Sale & Wanted had another 8,500. These are far from the only ones…

As for that Kevin Godley quote from the beginning of this chapter, it continued: ‘… though I no longer have a record deck.’ D’oh!

4

IN WHICH… VINYL ESCAPES FROM THE GRAVE

Like some kind of vinyl vampire, the long player refused to die, no matter how many times popular opinion wrote it off and consigned it to the dustbin of history. Slowly but surely it clawed its way out of the graveyards created for it when firstly CDs, then downloads and streaming looked to have all but buried it under a torrent of seemingly fatal disdain and abuse.

Vinyl was uncool, unloved, unmourned. Yet, though backing away to the musical margins, vinyl’s valiant rear-guard action not only halted its retreat, but fought off those who would condemn it to the past, and began to attract the attentions of contrarians, opinion-formers and hipsters cool enough to recognise its unique qualities and realise it still had much to offer.

Slowly, but inevitably, even big business began to notice the reactivation of the vinyl market. It must have done, surely, as while I was eating my breakfast recently, I looked at the box from which my wife was spooning her ‘Dorset Cereals’, made of trendy ‘nutty granola’. There on the back was the legend: ‘Life’s not a dress rehearsal… So, go on, join a choir, make a bark rubbing… go record shopping.’

The Times’ colour supplement magazine of 18 November 2017 featured in its ‘Shop! 150 Christmas Gift Ideas’ display, a full-page photograph of a Santa-and-his-sleigh toy figure and other items, all scattered on a turntable playing a 45 rpm single. Marks & Spencer featured the image of a vinyl record playing on a turntable as an important element of their Christmas 2018 TV advert. Not only that, McDonalds launched a 2019 TV advertising campaign promoting the addition of bacon to their Big Mac, with one of the scenes set in a busy second-hand record shop specialising in jazz. In May 2019 TV ads for a new Seat car featured what was clearly a second-hand record shop.

These and similar adverts and features are aimed not at me and my already hooked vinyl contemporaries, but at what they, and I, believe will become the new generation of vinyl fans, ensuring that records remain desirable objects for many years to come. Even we hardest of the hard proponents of second-hand vinyl will accept that there is a place not only for newly released reissues, but also for freshly released original records.

The only problem I can see with millennials embracing vinyl is its sheer cost. I have a very few newer acts in LP form – but I baulk at paying 20 plus quid for them – and I definitely won’t pay that for new editions of old records, the costs of making which were covered many years back. Don’t under-estimate the danger of greed once again putting vinyl’s future at risk.

That said, some of the new vinyl covers are extraordinarily attractive objects, and really can outshine even pristine old albums – but don’t have the built-in memories and effortless elegance of what we more mature types will always regard as the real deal.

Some vinyl has become so desirable and valuable over the past half a century that certain records must eventually become genuine antiques. Not, though, the LP featuring one of his own tracks that ‘Little’ Jimmy Osmond bought when appearing on TV’s Celebrity Antiques Road Trip, selling on for a tiny profit.

I am fortunate to own a good few records, originally sent to me to review when I was a local newspaper hack, and which I liked enough to keep, but which sold in such tiny numbers that they have acquired considerable rarity value. Largely ignored then, almost no one got to hear how good they were, even in the heyday of pirate radio stations. I had convinced myself on occasion over the years that I should cash in on the current value of these records as, surely, it must be set to plummet as vinyl ‘freaks’ begin to age and ultimately disappear. So, I took the plunge and offered some for sale. I sold a much sought-after album by a totally obscure band for a little under £400. It would have cost under three quid to buy it on its original release date. I let several others go for significant sums, but soon began to regret this aberration.

Not because the sales cost me potential profit – they didn’t really, because antiques, and record sell-on values are like shares – you can never really know for sure where the bottom or top range of their value is. Some long-standing valuable vinyls are, though, now beginning to shed, or not enhance, some of their financial potential as their current/prospective owners/purchasers die off.

My plan now is to hold on to most of my 1960s and early 1970s record rarities, so that I can not only enjoy the bragging rights of owning them, but also the memories they retain for me, regardless of value. It’s different, of course, even for confirmed collectors if someone offers you serious money for a record you don’t like. But then, why would most people have that record in the first place? The ones I didn’t like when I was reviewing were the ones which ended up in one or other of my local second-hand dealers’ shops.

My collecting of vinyl was definitely boosted by a man who inspired and promoted so many of the artists I grew to admire – John Peel. An article in the Radio Times many years ago was illustrated by a photograph of him in a room entirely surrounded by floor to ceiling shelves – all bulgingly full of LPs. I gazed at it, entranced, for some minutes, marvelling at what it would be like to own such a cornucopia of treasures and to be able to reach into it and discover at will something you’d be guaranteed to enjoy. From that moment, I set about emulating JP, albeit, inevitably, on a slightly lesser scale.

These days, of course, I no longer buy records I don’t already know and like – at least, not without listening to at least some part of them first. Really? Who am I kidding? I do, as you will no doubt have already assumed, frequently buy records just on the basis of looking at the cover, reading the sleeve notes, or second-guessing what the tracks will sound like, based on their titles and writers, the label the record is on, the year it was made and maybe the name of a session musician or two that I recognise. So I certainly do buy records blind or, at least, deaf…

I could check them out on YouTube first to hear whether I will like them – but the reproduction on my laptop is tinny, and really that also takes away much of the anticipation of owning a record I didn’t even know existed just a few minutes ago. Better to wait until you can play and hear it for the first time on your own. That way, no one else will get to hear should you have misjudged, and it actually sounds like a gang of squalling cats retreating from a bunch of barking dogs.

There is also the risk that if you ask to listen to the record in the shop where you’ve found it, the dealer will hear it and think, ‘Hm. That sounds better than I remember, I think I’ll keep it for myself.’ That’s genuinely happened to me before now. Either that, or someone else in the shop might offer more for it than you…

I have become acquainted with record shops of virtually every description – tiny, huge, filthy, spotless, floating, spooky, invisible, friendly, neutral, unwelcoming, expensive, reasonably priced, cheap, accessible, hidden away. One with a water well in it; one with water all around it. Others that also deal in fireplaces, boxing memorabilia, jewellery, menswear or offer wine-quaffing alongside the discs.