11,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Oldcastle Books

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

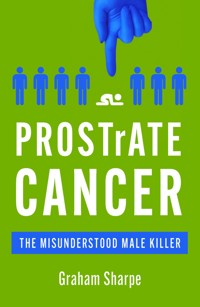

Prostate cancer really is the little understood male killer. 1 in 8 UK males will be diagnosed with prostate cancer, more than 130 new cases are discovered each day and, on average, one man dies from the disease every 45 minutes. Despite these statistics, and the fact that there are getting on for half a million men living with, or in remission from, prostate cancer in the UK, the condition is rarely discussed publicly and most men ignore the warning signs. Graham Sharpe wants to help change that. Faced with a sudden and unexpected diagnosis, Graham managed - just - to overcome a desire to punch the medic charged with the task of telling him he had prostate cancer but who was keener to answer his mobile phone, and set about trying to catalogue what he went through en route to acquiring the condition and how he dealt with the grinding process of his treatment, despite having no idea of the ultimate outcome. Along the way he met and befriended many others undergoing the physical and mental stresses of treatment, emotional turmoil comparable with watching their favourite football team lose every game they play. In this intimate memoir charting his own personal experience of coming to terms with prostate cancer, Graham brings humour and a light touch to a serious subject. Combating the shortage of reading material written by anyone with direct personal experience of the disease, this book seeks to educate the ignorant, raise awareness of the risks and dispel myths - including the widely held belief that the name of the disease is in fact prostrate cancer. Here's one man's personal truth about getting, having and possibly surviving prostate cancer...

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 532

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

THIS BOOK IS DEDICATED

to anyone who believes there are two ‘R’s in PROSTATE – I hope you don’t have to learn the hard way how to tell your ‘R’s from your elbow!

Letter in the Metro, 25 June 2021

‘I have lost count of the number of friends I know who have complained of “prostrate” problems. I have stopped bothering to correct them.’

– Ben Mundy, of Wells, Somerset.

FOREWORD

WHEN GRAHAM told me he had been diagnosed with Prostate Cancer it was at first a shock, but after I had taken the news in, all the previous GP and hospital visits he had been taking made sense.

He did not want anyone to be told, which I really didn’t like at all. That was something that I couldn’t do. So I made the decision to tell our two sons.

Our elder son, Steeven, lives in New Zealand, and we were going there to see him and his family for Christmas and New Year. I told him shortly after we arrived, and he took the news very well.

I then told Paul when we returned home, and it was agreed that when I updated him on G’s treatment and how he was feeling, he would keep Steeven in the loop.

This worked very well, and I felt much better, knowing that they were aware of what was happening. Graham was completely unaware that I had told them, but I felt then, and still feel now, that what I did was the right thing to do.

And now he knows what I did – as I have just told him.

Sheila Sharpe

INTRODUCTION

IN WHICH I PROSTRATE MYSELF

I VAGUELY recall having read an article many years ago, one phrase of which stuck in my memory: ‘Most people affected by the disease will die with prostate cancer, rather than from it.’ Thus it had never occurred to me to worry about the consequences of being diagnosed with prostate cancer, or ‘PC’, as I have come to call it. As a result of having read that article I did, though, at least become aware of the spelling and pronunciation of the word ‘prostate’.

Very few people – none, as far as I can recall – have ever told me of the time they found themselves or someone else prostate on the ground. Those who wish to, almost invariably use the correct word for that phrase – ‘prostrate’. There seems to be little confusion about the correct usage of the word prostrate in these circumstances. But many people have spoken to me about themselves or others being a victim of ‘prostrate cancer’.

I wonder why it is that a comparatively significant percentage of those who find themselves having to deal with the condition, or who are speaking of others who already have it, appear to struggle to name it correctly. I don’t find it disrespectful or upsetting when people use the wrong terminology, but it does strike me that perhaps there is an unwillingness amongst men of a certain age, predominantly those who are not suffering from this extremely common cancer amongst males of advancing years, to confront it. To the extent that they either genuinely do not, cannot, or will not absorb the pronunciation of the disease they fear that they, too, may find themselves having to deal with at some stage of their lives.

When those who are diagnosed with PC endure the ritual of confirmation, they may be temporarily shocked into a state of mind which doesn’t want to take in the enormity of what they are being told. Or they may feel that they have no intention of recognising the severity of the position into which they have just been inserted, for fear of the next step being to accept the potentially fatal consequences. Perhaps part of their rejection of the concept of having the disease manifests as not allowing its name to register. Or maybe – and this seems very unlikely – there are just too many hard of hearing, and/or illiterate men who are diagnosed with what they hear as prostrate cancer, possibly by less than clearly enunciating doctors, medics, specialists, consultants or oncologists.

Whether one calls it prostate or prostrate won’t affect the ultimate outcome, but, get it right, and at least you won’t be accused of not even knowing what you’ve been diagnosed with. Unless the accusation comes from someone who believes it really is called prostrate cancer, of course…

2

IN WHICH I WONDER HOW I HAD REACHED THIS POINT

MY EARLIEST indication of literally internal rumblings arrived on 11 December 2017, when I received a briefing on the results of an abdominal ultrasound which, wrote my GP, ‘show uncomplicated gallstones. In the light of these results we would suggest having a discussion about a surgical referral – and avoiding fatty foods as far as possible in the interim.’ Apparently, I was later informed, ‘uncomplicated’ didn’t necessarily mean uncomplicated. I may have got the wrong end of the stick, of course.

The best part of a year later, in October 2018, my gallbladder had left the building. More accurately, had been left in the building – the Central Middlesex Hospital. However, this satisfactory outcome did not mean that I could resume a life untroubled by medical issues, as I was now being gradually drawn into the process of receiving treatment for prostate cancer, although the medics had been happy that this shouldn’t delay the gallbladder removal as there was no direct correlation.

This newer situation had begun to reveal itself in early May 2018 when I learned that a urine sample I’d submitted did ‘show blood’. There was more on this subject from my trusted GP, who wrote: ‘The prostate does need to be checked via a blood test, then an appointment to see me.’

I duly took the PSA test and on 15 May 2018 was told: ‘Unfortunately the PSA has come back elevated (it was, I discovered, 40.46, which is not recommended) and this needs urgent further evaluation. I have taken the liberty of making an urgent referral to urology to investigate this further.’ Says the NHS: ‘The PSA test is a blood test to help detect Prostate Cancer. But it’s not perfect and will not help find all Prostate Cancers’.

It obviously was pretty urgent as I had an outpatient appointment scheduled at the Central Middlesex Hospital on 22 May – although, if I’m honest, I can’t now recall whether this was gallbladder or prostate-related, or a combination of both. But the next appointment was on 12 June at Northwick Park Hospital for a ‘Urology Flexible Cystoscopy’.

Mmm. That was something else.

Interestingly, the ‘consent form’ I had to sign began with a ‘Name of Procedure’ section which insisted they should ‘include brief explanation if medical term not clear’.

I got no explanation, but while I was disrobing prior to it being my turn, the chap before me, rather younger than my 67, walked into the changing room. He couldn’t stop laughing, in a slightly hysterical manner. ‘Oh, man,’ he said, looking at me and laughing some more, ‘Oh, man.’

A few minutes later, I knew exactly what he meant and was also feeling that the best way to cope with the situation was, indeed, slightly hysterical, disbelieving laughter, but minus the usual warm feeling which accompanies genuine guffawing.

You want to know what happened, don’t you? The official description is: ‘a telescopic examination of the lining of the bladder via the urethra (urinary tube). A local anaesthetic jelly is used to numb and lubricate the urethra to make passage into the bladder as comfortable (me, on reading this later – ‘hah!!’) as possible. Most patients experience some discomfort during the procedure (me – if you are one of those who apparently doesn’t/didn’t, kindly write to me, care of the publisher. I have zero anticipation that anyone will fit this description of experiencing no discomfort.) but the majority do not find it too troublesome.’

No, I didn’t find it too ‘troublesome’, but sitting there, aware of what was actually happening, really did cause one to think, ‘Is this actually happening?’ Even now, a couple of years down the line, writing this I’m thinking: ‘Seriously? They really did that? And I sat calmly and permitted them to do it!’

They also explained to me that I had to drink plenty of fluids for the next two days, and that for the next three or four I might find when passing urine that it would sting or burn slightly, and that my urine might be ‘slightly bloodstained’, but that all of this would ‘clear rapidly’.

And you know what? It did. It was. It cleared.

If that experience didn’t completely break my spirit, the one on 3 July 2018 for a ‘US-guided biopsy prostate transrectal’ came close to doing so – but for the intervention of a Kiwi nurse. The consent form offered a hand-written clue. Under the heading: ‘Serious or frequently occurring risks’ was scribbled: ‘BLEEDING, INFECTION, PAIN.’ And for suffering the risks thus described, what were ‘the intended benefits’? ‘DIAGNOSIS.’

Of course, I signed on the dotted line, then sat down amongst a small group of fellow victims to await the inevitable. I was the last to be seen.

If you don’t particularly want to know the gory details of what happened, I would advise skipping the next couple of paragraphs, which explain the procedure:

‘A small ultrasound probe is inserted into your back passage. The probe is slightly wider and longer than a finger. It is important to try and relax as this will make the test less uncomfortable. The doctor can then see an image of the prostate gland on a screen. You will be given a local anaesthetic injection into the prostate gland through the probe. Some small samples of tissue (biopsies) of the prostate gland are then taken, also through the probe. This can be uncomfortable but is not painful. The test should take about 20 minutes.’

Twenty minutes. That’s about half of the playing time of an LP.

‘The biopsies can be negative – no cancer seen. This is good news…’ But don’t get too excited, though as: ‘It is possible to miss very tiny areas of cancer in a set of biopsies.’

Then: ‘The biopsies may be positive. Not so good news.’

After the procedure you’re told to rest for a while. The info sheet suggested 15-20 minutes was appropriate, adding that it was ‘probably inadvisable to drive immediately after the test. Please drink some extra glasses of water each day for a few days.’

We were all told we couldn’t depart until we’d urinated after the test. Eventually I was the last patient left. I’d begun chatting with the New Zealand nurse. I have family in New Zealand. She had been exiled for some years, if I recall. I became aware that as soon as I was done she could go home, although not to New Zealand, of course. I began to feel guilty for keeping her waiting, even though she showed absolutely no signs of wanting me gone.

It took me a couple of hours to be able to go, before I could go… I’ll always remember that nurse’s patience and empathy. I know what a cliché it is to overpraise medics, and of course our emotions are heightened by our fears and state of mind at the time. But she was genuinely the difference between me heading home in a confused stupor and being able to do so in a calm, collected fashion, satisfied that one of my worst experiences was now, literally, behind me…

This is from the NHS website (in December 2020):

There’s currently no screening programme for prostate cancer in the UK. This is because it has not been proved that the benefits would outweigh the risks.

PSA screening

Routinely screening all men to check their prostate-specific antigen (PSA) levels is a controversial subject in the international medical community. There are several reasons for this.

PSA tests are unreliable and can suggest prostate cancer when no cancer exists (a false-positive result). Most men are now offered an MRI scan before a biopsy to help avoid unnecessary tests, but some men may have invasive, and sometimes painful, biopsies for no reason.

Furthermore, up to 15% of men with prostate cancer have normal PSA levels (a false-negative result), so many cases may be missed.

The PSA test can find aggressive prostate cancer that needs treatment, but it can also find slow-growing cancer that may never cause symptoms or shorten life. Some men may face difficult decisions about treatment, although this is less likely now that most men are offered an MRI scan before further tests and treatment.

Treating prostate cancer in its early stages can be beneficial in some cases, but the side effects of the various treatments are potentially so serious that men may choose to delay treatment until it’s absolutely necessary.

Although screening has been shown to reduce a man’s chance of dying from prostate cancer, it would mean many men receive treatment unnecessarily.

More research is needed to determine whether the possible benefits of a screening programme would outweigh the harms of:

overdiagnosis – people being diagnosed with a cancer that would never cause symptoms or shorten life expectancyovertreatment – people being treated unnecessarily for tumours that would unlikely be harmfulWhat’s a raised PSA level?

The amount of PSA in your blood is measured in nanograms of PSA per millilitre of blood (ng/ml).

If you’re aged 50 to 69, raised PSA is 3ng/ml or higher.

A raised PSA level in your blood may be a sign of prostate cancer, but it can also be a sign of another condition that’s not cancer, such as:

an enlarged prostateprostatitisurinary infectionHow accurate is the PSA test?

About 3 in 4 men with a raised PSA level will not have cancer. The PSA test can also miss about 15% of cancers.

Pros and cons of the PSA test

Pros:

it may reassure you if the test result is normalit can find early signs of cancer, meaning you can get treated earlyPSA testing may reduce your risk of dying if you do have cancerCons:

it can miss cancer and provide false reassuranceit may lead to unnecessary worry and medical tests when there’s no cancerit cannot tell the difference between slow-growing and fast-growing cancersit may make you worry by finding a slow-growing cancer that may never cause any problemsFriday 10 August had been on my mind while I was on holiday, and on that precise date I duly put in an appearance at Northwick Park’s Isotope Scanning facility for my ‘NM bone whole body’ Isotope scan.

Radioactive liquid was injected into a vein in my arm – no, couldn’t tell you which.

‘You will be required to drink extra fluids and empty your bladder regularly between the injection and the pictures.’

Then I was called to see Dr A on Monday 24 September at 2.20pm at Northwick Park. This resulted in Dr A sending me a copy of the letter she sent to the consultant urological surgeon, Mr Giles Hellawell, telling him: ‘We have been through the rationale, practicalities and expected side-effects of radical radiotherapy to the prostate and pelvis. He will need to remain on LHRH analogues for a minimum of two years. He is due to have the cholecystectomy (surgical removal of the gallbladder) in October and therefore we have agreed to meet in November to plan his radiotherapy for the New Year.’ That was all accurate but like, I suspect, many other patients, when I’d had meetings with Dr A I’d heard and agreed with what she’d told me, but found it difficult afterwards to retain the information she’d given me, other than in the vaguest detail.

As Santa was preparing for his busiest evening of the year, I received good tidings from the Mount Vernon Cancer Centre, dated 24 December 2018, whose anonymous ‘secretary to clinician’ was writing to confirm that an outpatient appointment had been arranged for me to be seen at the Mount Vernon Cancer Centre ‘under the care of: Dr A on 14 January 2019 at 14.30 in MVRG/GEN1’.

Happy New Year to me, eh?

There followed copious information about how to access the relevant car park and a semi-upper case warning that ‘PARKING FINES’ were ‘in operation’. This possible harbinger of doom was only slightly diluted by a reminder to bring the letter along with me ‘to provide confirmation that’ I was ‘a patient receiving treatment in the Cancer Centre to receive a reduced rate parking token’. What a relief to learn that acquiring a Premier League medical complaint entitled me to pay less than other merely fit mortals to park my car.

Of course, I had a trump card to play here – my Freedom Pass, acquired via great age, entitling me to completely free travel on the buses and Tube trains which could put me adjacent to the Mount Vernon car parks and in a position to guffaw and snigger at the poor car-bound travellers forced to shell out to attend their cancer treatment.

Three hours before the meeting with Dr A, though, I was ‘invited’ to attend a Pre-radiotherapy Group Information consultation, which was to last about an hour and end with refreshments at the on-site Lynda Jackson Macmillan Cancer Centre, a drop-in Centre for patients to talk and ask questions about all aspects of cancer and its treatments. We were indeed given a chatty welcome, herded around and shown where we would be receiving our treatment, and invited to ask questions.

It was a good PR exercise, but how much actual knowledge any of us acquired would be open to discussion. Although I enjoyed the cup of tea afterwards, it would be the last time that I would enter the Lynda Jackson Centre – no, I wasn’t banned, I just didn’t really think it offered anything that I specifically needed at the time. I would, though, certainly not try to prevent anyone else from taking full advantage of the facilities. It would definitely not be sensible to dismiss it without checking it out first, either.

Whilst there we were handed a great deal of bumpf from Macmillan, offering all sorts of information about all aspects of PC – including something I never ever plucked up the courage to use… The Macmillan Toilet Card…

‘You can use this card during or after treatment. If you need to use a toilet urgently, you can show it in places such as shops, offices, cafes and pubs.’ …yes, I’m sure one could, but equally, I just never would. This is purely a result of my own ridiculous self-esteem. I genuinely could not bring myself to admit in public that I was so likely to wet myself that I had to produce a card to prove it, thus doubly embarrassing myself!

Of course, I have kept the card ‘just in case’ I might ever need to use it and be so drunk I’d dare to… Please don’t emulate this totally foolish attitude should you ever be offered a ‘Toilet Card’. There’s nothing to be ashamed about in requiring to use one. Bear in mind that in late November, 2021, it was revealed that one in five public toilets in the land have been closed over the past six years.

A couple of hours later I was seeing Dr A, who was very reassuring about the treatment I would be undergoing. I think she liked me, mind you. Well, I saw a couple of letters she’d written to my GP about me, in which she’d written, ‘It was a pleasure to see Mr Sharpe…’ and ‘It was a pleasure to speak with Graham today…’ As well as calling me ‘this gentleman’.

Nor was she alone in this positively positive attitude towards me. A clinical oncology specialist who wrote about me declared: ‘It was a pleasure to meet Mr Sharpe…’ A locum consultant surgeon penned this: ‘Thank you very much for allowing me to see this pleasant 69-year-old gentleman…’ While yet another medic agreed: ‘It was a pleasure to review Mr Sharpe…’ Nor must I overlook the consultant orthopaedic surgeon I also visited: ‘Many thanks for sending this nice man up.’ His comment may have unknowingly told the truth – they were all just sending me up!

Clearly, though, all of these medical experts are instructed and/or trained to write their letters in a specific manner, and to ensure they compliment and respect their patients along the way. I have to admit that it does encourage the patient to think well of them – except, of course, for the arrogant, unfeeling bas*ard who broke the news that I had PC to me so gently.

3

IN WHICH THE PROBLEM BECOMES APPARENT

THE GENESIS of this book was the operation to remove my gallbladder in October 2018. In the build-up to this, I had to undergo various tests and procedures, being poked, probed and prodded innumerable times, all the while not having much idea precisely what each succeeding investigation was being done for, but knowing it was likely to lead to a conclusion as to whether or not I would be retaining the gallbladder, to which I had become rather attached over the past 60-plus years.

I wondered whether not only the imminent gallbladder operation would need to be cancelled, but also our scheduled trip to New Zealand to see our two-year-old granddaughter. The unanimous decision by the medics I asked was that neither should be. That in itself made me feel a little better about the PC which they clearly didn’t think was about to carry me off to my coffin.

My ignorance of medical matters was pretty much complete at this time. Not since the removal of a cartilage during the 1970s had I been admitted to hospital and my health had been consistently good overall. There had been a couple of small ops for carpal tunnel syndrome, one for each hand, but they didn’t even involve overnight stays.

However, after experiencing stomach discomfort sufficient to prevent me being able to join friends and family dining out on several occasions, I had realised there was almost certainly something not quite right. I was right that things weren’t right, which was how I ended up in the Central Middlesex Hospital, being de-gallbladdered.

This did involve an overnight stay in hospital, partially because when I was taken in to be operated on, an important-looking part of the equipment on which I was lying fell off unexpectedly. Blank looks all round in the theatre, but it was eventually repaired – or stuck back on – and I was duly anaesthetised and deprived of the gallbladder, albeit by then too late to be sent home that night.

Five days later I was in Liverpool with wife and friends, enjoying visiting the sights and hearing the sounds of that excellent city, and becoming stronger with each passing day. However, my optimism that this would be the end of my recent acquaintanceship with medical matters and venues was to be short-lived.

On the last day of January 2019 I enjoyed an excellent lunch with a small group of friends at the Betjeman Arms pub at St Pancras Station, feeling that things were going well. A bottle of Kiwi sauvignon was quaffed, celebrating the fact that I had recently returned, with wife Sheila, from the Christmas trip to New Zealand to catch up with son, Steeven, his wife Nicole and infant granddaughter, Georgia.

But the next day I not only spotted signs of blood in my urine, but also found I was needing/having to urinate more frequently. Perhaps I had cystitis. Whether as a result of preparatory tests for the gallbladder operation, or my own subsequent apprehension at noticing intermittent discolouration in my urine, I had recently taken my concerns to my GP, who had initially sounded confident that there wasn’t anything drastically wrong, but had reacted very quickly when a PSA blood test result revealed a concerning level in the 40s, and sent me off for a sequence of investigations, each of which seemed to lead seamlessly to another, even though I was still regularly advised that I shouldn’t be overly concerned. These investigations incorporated procedures I had never in my wildest dreams expected to experience.

Notably: Twice having a camera inserted down into my penis. Three, maybe four times (I gave up counting) having a finger – someone else’s – inserted into my rectum. Undergoing a prostate biopsy, as well as the ‘insertion’ of fiduciary pellets, when I had been anticipating only a chat with a medic. And during the latter intervention, an unexpected request from a nurse to: ‘Please hold your testicles out of the way.’

I submitted docilely to each successive experience – ‘Just pop your legs up into these stirrups’, ‘Lay down and relax while I…’, ‘Now, this shouldn’t feel too…’ – actually, almost enjoying them as potential anecdote fodder to some extent, once I’d rapidly realised that the most important element of this probably lengthy situation was to park one’s dignity firmly at the door and just do what I was asked, without objection and without really knowing why it was happening.

When subsequent body mining had made it obvious that I was indeed suffering from prostate cancer, it was equally obvious that I didn’t have much of a clue what that really meant. Once I accepted that I did have PC, and that it almost certainly wasn’t going to go away, I decided that, without having much choice in the matter, I’d better go along with the advice given and the treatment offered. At this point I hadn’t told anyone, other than Sheila, what was going on. Should I survive, I vowed to tell family and friends precisely what had happened and how I’d coped – preferably in technicolour detail.

I wanted to be able to tell them about my experiences and to warn the men to get themselves checked out on a regular basis, in case they might be at risk of following the same path with, possibly, a worse outcome. I wanted to do so, using my own experiences as first-hand evidence, and to be able to put into their own minds the possibility that they too might have to travel the same route at some point, and to be aware, I hoped, that it needn’t necessarily result in a literal dead end.

I’d heard and read stories about celebrities who had suffered from PC and survived – Rod Stewart, Stephen Fry, Elvis Costello, Robert De Niro, Harry Belafonte, Roger Moore, Ian McKellen and Bill Turnbull amongst them. Golfer Arnold Palmer even founded the Arnold Palmer Prostate Center following his diagnosis. But few of these celebrities’ comments and little of their media coverage delved in any detail into what such a diagnosis meant for the recipient. Odd that almost all of them (maybe Mr T gets an honourable exemption), people usually so keen to publicise their every move, change their tune when they are unwell and during their treatments.

I decided to tell of my path to diagnosis in detail, what goes on during treatment, of any potential ‘cure’ and all that would happen to me along the route. Of the people in similar and worse positions that I met and bonded with during the hours spent being given the significant doses of radiotherapy I underwent – which also meant that I would have to drink an alarming amount of water during the process. In my case, with two buses and a Tube train to negotiate, followed by a dash for home, all with a bursting bladder, this required no insignificant planning in order to ensure I arrived home with still-dry trousers…

Before we really get into this story, though – although I don’t want to come across as an unreconstructed pessimist – I have to say I just cannot accept that anyone can actually ‘battle’ against cancer. I certainly didn’t. I endured it, for sure. Lived with it, yes. Came to terms with it, possibly. Worried about it. Stressed out over it. Wondered about it. Confronted it, even. All of those things.

But battled, fought, struggled against it, took it on? No, I don’t think so. I don’t see how one can. You just submit yourself to the steps the doctors tell you are necessary to give yourself a chance of surviving, even though this will ultimately mean living with what has already happened to you once, and could easily return to do so again.

I’m also not that sure you can ever actually ‘beat’ cancer. You might be told that your treatment has done what it set out to do, and that, as of now, all of the indications are that you are no longer a cancer patient. But, as far as I have understood things, such a verdict can never guarantee that it can’t return, or that you won’t find yourself affected by another variant of the disease.

Support for this point of view emerged from an unexpected source in December 2020 when former Woman’s Hour presenter Jenni Murray appeared in an ITV programme called The Real Full Monty On Ice, in which she joined other celebrities promoting cancer charities by stripping on ice live. Jenni, who had had a mastectomy for breast cancer in 2007, declared: ‘You don’t battle cancer, or fight it, or beat it. You have it and you get on with it.’

TV presenter Bill Turnbull, who has PC, observed: ‘You can’t fight cancer, you just have to deal with it…’ They were both absolutely spot on.

4

IN WHICH I RECEIVE A SPICY WELCOME TO LA

I WAS scheduled to begin the first of 20 radiotherapy treatments, intended to reduce my PSA levels, on Monday 4 February 4 2019. But for the preceding few days the frequency with which I was needing to pass water was definitely increasing. Over the weekend I was seeing blood in my urine and I began getting up two or three times each night to go. Perhaps I had cystitis again? Or it could just be a reaction to those fiducial markers, I supposed. That, and the fact that the need to remain well hydrated, drinking two litres of liquid per day, was obviously going to increase the frequency of going.

But I really wasn’t happy about the visibility of blood. So I forfeited a Saturday night out and on Sunday went online to book a GP appointment for Tuesday morning, even though I should by then have begun my radiotherapy treatment and could have perhaps asked then whether this was something or nothing.

Regarding my first radiotherapy appointment I had no idea whether I should report for duty with a full or depleted bladder. I’d previously been up with a group of around a dozen or so other imminent patients to be given a bit of a tour of facilities and an indication of what would happen when and how. I’d also been called in to have a CT scan, prior to which I was asked to drink half a dozen cups of water. I’d later learn (if I had understood correctly), that this was something of a dummy run, designed to reveal certain items of information which would be used to assess the conduct of the daily radiotherapy appointments.

My route to Mount Vernon was not that difficult. Starting with the H12 to Pinner Green. I’d gambled that I had time to visit the post office before catching the bus but as I exited from sending off a package, into the rain, there was the arriving H12. Could I shift quickly enough to catch it? I jogged towards the bus stop, waving like a demented windmill. Not only did the driver see me, he reopened the closed doors to let me on.

At Pinner Green, a brief wait for the H11 straight to Mt V, a mere hour and a quarter early. As I walked damply towards my fate I spotted an on-site charity shop, and bought a David Bowie CD for four bob, surely a good omen for today’s adventure.

I used the new-fangled, now soggy, check-in ticket I’d been given, which showed that I had been allocated ‘Machine LA 10_2018’ at noon. Up came confirmation that I was now to report to LA3 at 12.05. Not a major inconvenience, timewise, but it transpired that LA3 was the only machine without a dedicated waiting room.

I was told to sit in the dimly lit general waiting room and, well, yes, wait for a call. Oh well, I thought, it will be quite interesting to sit amongst the masses who know more about the procedure than a newbie like me.

In such situations I usually prefer to look for a corner position to gaze out at others from, rather than be one at whom others are gazing. Instead, I told myself that as I was about to commence an altogether alien experience it might not be a bad idea to take notes and to begin a treatment diary.

I soon heard patients who were clearly already old hands at this business, chatting about their individual thoughts. Some were complaining about how tired their treatment made them. It was also immediately evident that there were a wide range of complaints and illnesses being treated here, but, crucially, we were all in ‘it’, whatever ‘it’ might be for each specific one of us, together.

Said the wife of one patient: ‘The other night we were sitting up at 2 am watching the Men Behaving Badly Christmas Special from 1980-something.’ Desperation tactics, indeed.

I heard grumbles about the difficulties of accessing the confusing reduced car parking facility for cancer patients. Others were talking about breakfast. I’d had a very early morning slice of toast followed by half a bowl of cereal… I wasn’t sure whether this might leave me feeling weak after the treatment. Well, I thought, I’ll soon find out.

Steam was rising from damp raincoats, wet footwear and, in my case, a dripping brolly and leather hat, which were slowly drying off, as the packed room held a good number of people waiting for appointments for consultations, follow-ups and treatments.

I noticed a small café dispensing hot drinks, sandwiches, rolls, biscuits and crisps, all at very reasonable prices. Trade was brisk at just after 11am. My gallbladder-free stomach began to rumble a little.

The majority of patients were looking at their mobile phones. Notices on the wall warned against using mobile phones. Being an obedient lad, I’d turned mine off and put it away. I waited in vain for anyone to discipline the illegal users.

A nurse chatted to a handyman who had arrived in the room carrying a step ladder, telling him: ‘The poor patients are complaining because it’s so dark in here – and if they’re not, they’re complaining because it’s so cold.’ She turned and addressed the crowd: ‘I’m after two young men…’ There were one or two sniggers as the two she was after revealed themselves and she took them away. Who knows where to?

Then I was called for and taken into a room, to be told: ‘Empty your bladder.’ I had to ask where. Having complied, I was then asked to empty some more to provide a sample, after revealing that I had been seeing blood in my urine sporadically over the weekend. Of course, I could no longer go, having previously done so. So, I had to drink some water to help produce the goods. A charming nurse was fussing over me as a result. A couple of glasses of ice-cold water finally provided a successful conclusion as I silently told myself, ‘It makes a change for you not to be taking the piss, but giving it, instead.’

It was tempting to believe that this chain of events was some kind of daily comic sketch laid on for the benefit of newbie patients to calm their nerves. A man walked up to the radiotherapy coffee bar ‘Managed by Comforts Fund Charity’ counter, holding two empty bottles, and asked the lady behind the counter to fill them. She appeared to be considering whether to ask him precisely how she should do so. Then the man with the step ladder wandered back in, without actually mounting it or appearing to serve any particular purpose. At this point, a man looking rather closer to death’s door than anyone else in the room was wheeled through on a bed, on his way to who knows where… Now a guy dressed like a refugee from a hippie music festival sashayed in, somewhat spoiling the grand entrance by dropping a packet of tissues on the floor.

I’d no idea whatsoever how long it might take to run a check on a urine sample, but I began to worry a little when no one came to tell me it was time to drink the six glasses of water I’d been informed were required. Earlier on I had, though, been warned things were running a little late. But what constituted ‘a little’? I turned my attention to thinking about the birthday trip to San Francisco I’d booked for my wife and me, knowing that it was one of her ambitions to visit the famously bridged city. I’d been told that the after-effects of my treatment should be over in seven – or so – weeks after it had finished. Which should, I was hoping, just about meet the date we were due to travel.

Suddenly I heard the café lady ask a customer: ‘Where are you from?’

‘Ware.’

‘Yes, where?’

‘No, Ware…’

‘Nowhere?’

‘… in Hertfordshire.’

The café lady told her colleague that people were buying her cakes and sandwiches to take home with them. Cost or taste, I wondered? I hadn’t yet sampled them for myself. With tea, coffee, Bovril at 90p, bun/butter for £١, crisps 70p, Cheddars 80p, cake £1, milk 35p, soup 80p, hot chocolate 90p, toast 30p per slice, we’re spoiled for choice. Even better, food hygiene rating: 5 out of 5.

The chatty nurse asked a lady what colour she intended to dye her hair.

‘Violet.’

No one stayed anonymous for long in there, as various people wandered in with clipboards and shouted out to the room in general:

‘CROW? Paul Crow…’

‘TYSON? Henry Tyson…’

‘BITCH!’ The nurse didn’t seem to be shouting at anyone, but… ‘Bitch?’ she said again.

‘BITCH?!’ Again, louder… ‘Valerie Bitch?’

Ah, yes, here she was – Valerie BEECH, apparently used to the mispronunciation…

‘WINDY?’ I’ll let you guess…

Eventually I was called to drink my six glasses of H2O. Out into the corridor to find a dispenser. Sounds easy enough, but it turned out not to be the most pleasurable of tasks, and this was Day One. Phew, done. Back to take a pew again, preparing for… whatever. It feels like the water has gone to my head…

A lady is instructing a nurse about how ‘faith’ is a ‘really important’ part of her life. She emphasises: ‘We keep on going day after day.’

Having been told I’d need a dressing gown in which to receive my treatment, despite not possessing such a thing, I was surprised to then be informed, ‘Okay, just keep the top you have on, that’ll be fine,’ as I was called in to be zapped. I’d removed my shoes and trousers, retaining pants and socks. The lady in charge asked me to confirm my address and date of birth… ‘That’s my birthday, too’ she said, adding quickly, ‘A different year, though.’ We shook hands, two people linked by a random date. What are the odds? Well, obviously, 364 and a bit/1 – the ‘bit’ included to allow for leap years.

They put me on the machine, just stopping me in time from lying down the wrong way round. ‘Don’t move yourself when we move you,’ I was warned, a tad confusingly.

There was a senior medic, male, with a colleague, female, there too. Both matter-of-fact but friendly and efficient sounding, as they lined up my ‘tattoos’ with, I imagined, my fiducial markers.

Ah, yes, the fiducial markers, aka fiduciary pellets. They’d been ‘fitted’ a while earlier. ‘Fired’ might be more accurate. That had been, er, an interesting experience. I won’t bore/frighten/disgust you with the gory details (which, safe to say, involved some kind of apparatus which reminded me of the steps on a rope ladder up to a trapeze, although I could have been hallucinating at the time), but instead quote from a website which seems to replicate my memorable experience which, once endured, I tried to lose the memory of as quickly as possible! Seriously, though, another example of parking one’s dignity and just letting them what knows get on with it:

Fiducial markers are used to help target the radiation at the prostate gland better. They are tiny, smaller than a grain of rice. They are made of pure gold, so the body does not react with them.

Three seeds are injected into the prostate gland by your urologist or sometimes by another physician. The procedure is very similar to a biopsy: you need to do a bowel cleanse with an enema or magnesium citrate beforehand. You need to take preventative antibiotics for a few days, usually starting on the evening before the procedure. You may be given a sedative at the time of the procedure. An intrarectal ultrasound is used to help guide the insertion of the ‘needle’.

One advantage of this compared with the biopsy is that there are only three needle pokes instead of twelve!

The three seeds form the corners of a triangle inside the prostate. When the radiation therapist sets you up for treatment each day, they do a scan which shows the marker seed triangle, and they can finely adjust the treatment table position so that the three seeds line up perfectly with where they are supposed to be. This helps the treatment machine “lock in” on your prostate gland. Think of it as GPS for your prostate.

The other great benefit of all this is the anticipation that one day I’ll be asked at an airport check-in whether I have anything of value to declare, and be able to admit: ‘Yes, three pieces of gold. Would you like to see them?’

As for the ‘tattoos’… I’d always vowed I’d never have one on my body, but I ended up with three, courtesy of PC. Only small ones, and they don’t feature slogans or represent loved ones, flags, rock stars, or football clubs. They’re blue and initially, I was not really sure what they were put in place for, to be honest. Also helping to line up the zapping rays, I guessed. Cancer Research UK know for sure, though, who say:

During your radiotherapy planning session, your radiographer (sometimes called a radiotherapist) might make between 1 to 5 permanent pin point tattoo marks on your skin. For some types of radiotherapy, for example, electron treatments, you won’t have tattoo marks.

Your radiographer uses the tattoos to line up the radiotherapy machine for each treatment. This makes sure that they treat exactly the same area each time.

I’m proud of my three, but rarely show them off these days. Anyway, back to me, stretched out awaiting my first dose of radiotherapy…

‘That’s it. We won’t be a minute,’ says the medic guy, as he and his sidekick bolt for the door to get outside as fast as their legs can carry them: in well under a minute as it happens. For what seemed like between ten and fifteen minutes I lay passively, with my hands knitted together on my chest, listening and watching, fascinated, as the radiotherapy machine buzzed, clicked and whirred, and its laser shifted around me several times. I couldn’t feel much at all, although I imagined I was experiencing some level of warmth being projected into my nether regions.

There was a rather tinny, pop-y style of background music playing which did not appeal to, or comfort, me. Once the machine had stopped and the huge, thick doors of the room reopened, I was swiftly told to dismount and dress before departing from the room.

‘How was that?’ I was asked by one of the radiotherapists once I’d emerged.

‘Absolutely terrible. I’m shell-shocked. If that’s what it is going to be like every time, I’m not coming back,’ I told her. She looked crestfallen.

‘Oh dear, what happened?’

‘I had to listen to the bloody Spice Girls in there. If that’s going to happen every day, I’m out of here.’

She laughed. ‘Oh… you can bring your own music if you like.’

So, in the future, I vowed I would do so.

Setting off home, I quickly realised that finishing the treatment each day was not going to be the most difficult element of the entire experience. Getting home with dry trousers and pristine pants would be.

I’d utilised the facilities before leaving to wait at the bus stop terminus within the hospital where I was going to catch the H11 to head back homewards. But bus was there none to be seen. There was one due. But how long until it arrived? Remnants of the six cups of water were beginning to stir and inform me that they would like to emerge. So, I popped back to liberate some more liquid.

Still no bus when I returned. Looked like traffic problems were to blame. I began to walk, planning to make it to the nearest Tube station at Northwood. I passed a car whose frontage had been staved in, then decided to catch the 282 bus when it came along, which dropped me off at the station, whose platform boasted a red-coated lady walking up and down whilst plucking away at a Jaw harp.

I got off at Pinner where I had to bolt into the gents before emerging to catch the H12 home, speaking sternly to a boisterous schoolboy who tried to queue-jump: ‘Oy, you little jerk, I haven’t been standing here waiting so that you can jump in front of me, piss off… !’ (Before I do just that, I didn’t add!) The young lady getting on in front of me thought I was aiming these remarks at her. Awkward.

The next day I had an appointment at my local GP practice for a urine test, before heading back to Mount Vernon for Day Two. I acknowledged a small gesture of kindness by the bus driver to an elderly chap – no, not me – having difficulty in walking and carrying a large shopping bag. The driver generously stopped the bus before the scheduled stop in order to leave him nearer his destination.

I was again in time to drop into the charity shop at the hospital, this time snapping up CDs by veteran pop stars Crispian St Peters and Tommy Roe – 20p each. What do you mean you’ve never heard of them? ‘You Were on My Mind’ and ‘Pied Piper’ were CSP’s chartbusters, ‘Sheila’ and ‘Dizzy’ were big hits for Mr Roe on both sides of the Atlantic.

I started chatting with the elderly lady (a good two years older than me) behind the counter. Like a verbal game of tennis, we lobbed back and forth the names of forgotten (by all but us) pop stars like Wayne Fontana, to which she countered with Long John Baldry; and Gene Pitney, to whom she retorted with Freddie Garrity. I enjoyed this diversion so much that I forgot to ask for change from the 50p piece I’d handed over, thus boosting the day’s profits for them by two bob (younger readers, ask your grandmother!).

Having checked in again, I was soon ensconced opposite the café, in time to hear a heated discussion which featured the phrase: ‘She’s so competitive – it’s just a bloody game!’ Rather the point of any game worth playing, surely? I thought.

The café display was somewhat reduced today – no cake or buns to be seen. Yesterday’s somewhat under-employed handyman reappeared, minus his step ladder, but plus a colleague. They studied the lights illuminating the waiting rooms. ‘That’s good, only two bulbs missing,’ observed one. ‘Just as well. We haven’t got any more than that,’ replied the other.

The lady from ‘where, Ware?’ was also back from Warever, revealing to the much younger lady sitting next to her that she’d had a heart attack and hysterectomy – not, I very much hoped, concurrently. At this point my concentration was interrupted by the radiographer telling me, as though she were the starter for a Grand Prix, to ‘Start your waters…’ Six more cups of, this time room-temperature, H2O – preferable to the freezing stuff, I’d decided. Before I went, I heard Mrs Ware telling her companion that of the two, the hysterectomy was the more pleasurable experience.

By now I’d taken to encroaching on the ‘posher’ part of the not-overly-posh (but bloody wonderful, nonetheless) hospital. For ‘posher’ read ‘private’, so it was no surprise when I nipped into their section on the excuse of using their water-dispensing machine pre-treatment, to discover I was able to watch a few minutes of Wanted Down Under, a daytime TV favourite in which some working class Brits, pretending to fancy moving to Oz or New Zealand, are flown over to one of those two countries, shown loads of houses they can’t afford, offered jobs which will pay poorly, then asked to decide what they wish to do. Which is almost invariably – having seen members of their families tearfully begging them not to go (despite probably not having actually seen them for years) – that they will stay home, no doubt to the relief of Kiwis and Aussies everywhere.

A very posh-plus couple were sitting watching the programme. ‘We used to play golf every day,’ they said, ‘when we lived in America.’ But now, they confessed, ‘not so much’.

I think the posh gent’s treatment was coming to an end, either that or he’d upset the chap at reception, who was now telling the posh man that he hoped he wouldn’t have to see him again, but wishing him well for the future. While the posh man popped to the gents prior to leaving, his wife confessed to the receptionist that she could smell the treatment he’d had on him when they drove home together in their posh car. She didn’t actually say the car was posh, but it seemed an odds-on shot.

On my return to the waiting area, two young ladies were discussing their cancer-treatment hair loss. One pulled out a wig:

‘£15.99 on Amazon,’ she laughed.

The other – ‘I’ll be 51 in May’ – had paid £72 for hers, albeit ‘with a voucher’.

‘Yes, I think it’s synthetic,’ said the £15.99 lady, ‘but it looks quite nice on me.’

They then discussed how other wig wearers could possibly pay ‘two and a half to three thousand…’

The 50-year-old tried on her friend’s wig, brushed it into place and added a hat. ‘I look like Kim Kardashian now,’ she said, as the pair took selfies of each other, laughing uproariously.

A girl in a bobble hat was sobbing. Her male companion stroked her head. I think she was the one there for treatment.

Much earlier than had happened the day before, I was being pushed and shoved into place on ‘the slab’. Tuesday’s audio entertainment – I’d forgotten to bring my own – was Robbie Williams’ ‘Angels’, followed by Britney Spears, then Cher, then young-folk stuff, of which I had no recognition factor.

‘Don’t you have any heavy metal?’ I asked a baffled-looking radiotherapist, before quickly re-robing, squeezing out as much as possible of those six cups’ worth of water, dashing off to jump on the waiting H11, followed by another short wait for the H12 and finally back indoors – admittedly straight to the bathroom – before my favourite soap, Doctors, started at 1.45.

Shock news on Wednesday, 6 February: I was to switch from LA3 to LA10! Promotion or relegation? I had no idea.

Promotion, I guessed, as LA10 had its own waiting room, with two people doing just that when I arrived. One of them, a chap who had driven 40 miles to get here, and the other, a lady from Wembley, who was worried about the driver of the vehicle sent to collect her who kept knocking on the door. ‘My dog goes mad if anyone knocks on the door,’ she fretted. Yes, but could the dog bring her to LA10? I doubted it.

Almost as soon as I arrived, they asked me to begin drinking. I lost count during the process, so when I got to what I wasn’t sure was either the fifth or sixth cup, I decided to swig an additional half, thus knowing I was only either half a cup over or under the required dosage.

I was called for shortly after, and my treatment began 15 minutes ‘early’. I had a laugh with the radiographers who again confirmed that they had no objection to me bringing my own CDs in, if I could actually remember to do so, and also because they played me two Phil Collins or Genesis tracks, followed by Bon Jovi’s ‘Living on a Prayer’, the latter of which I said I hoped wasn’t their diagnosis of my condition… However, when they finished the session with more Spice Girls, I knew it was definitely time to fight back with my own selections.

I was dismissed, clutching a new dressing gown for future appointments. But I was far from sure if I’d ever use it.

Opting for a slightly different trip home I caught a 282 bus, quickly visited a couple of charity shops in Northwood, then jumped on a passing H11, on which were some elderly (well, by my standards, anyway) ladies who had all been to the same meeting. One was telling the others how much she loved eating fish.

‘Can’t see your fins yet,’ replied another.

I had to almost physically restrain myself from butting in with, ‘Sorry, ladies, fins ain’t what they used to be.’ Fortunately I’d already got my coat…

I realised that the medical experts really hadn’t been joshing when they banged on about pelvic floor exercises helping to extend urination intervals, after I had to get up twice overnight to relieve myself. I told myself firmly to start pelving seriously. I’d also read that Pilates can be helpful in that respect, so I thought I might have a chat with my next-door neighbour, Dr Phil, who had been trying to persuade me to join him in his weekly classes.

I struggled to get an empty bladder on Thursday morning, prior to leaving for Mount V. I was allocated LA10 again and was in position bright and early.

Forty-Mile-Each-Way Man was in residence, as was a family of three: the early-middle-aged (hope she doesn’t read this if she turns out only to have been 26) female patient with a supportive crutch and her mum and dad. The latter was a former cricket umpire who, it turned out, was listening to a Big Bash cricket match on his radio as we waited.