4,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

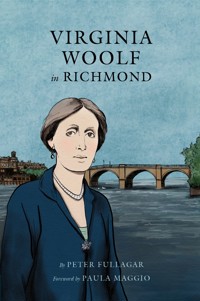

- Herausgeber: WS

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

"I ought to be grateful to Richmond & Hogarth, and indeed, whether it's my invincible optimism or not, I am grateful." - Virginia Woolf

Although more commonly associated with Bloomsbury, Virginia and her husband Leonard Woolf lived in Richmond-upon-Thames for ten years from the time of the First World War (1914-1924). Refuting the common misconception that she disliked the town, this book explores her daily habits as well as her intimate thoughts while living at the pretty house she came to love - Hogarth House.

Drawing on information from her many letters and diaries, the author reveals how Richmond's relaxed way of life came to influence the writer, from her experimentation as a novelist to her work with her husband and the Hogarth Press, from her relationships with her servants to her many famous visitors.

Reviews

“Lively, diverse and readable, this book captures beautifully Virginia Woolf’s time in leafy Richmond, her mixed emotions over this exile from central London, and its influence on her life and work. This illuminating book is a valuable addition to literary history, and a must-read for every Virginia Woolf enthusiast…”

- Emma Woolf, writer, journalist, presenter and Virginia Woolf’s great niece

About the Author

Peter Fullagar is a former English Language teacher, having lived and worked in diverse locations such as Tokyo and Moscow. He became fascinated by the works of Virginia Woolf while writing his dissertation for his Masters in English Literature and Language.

During his teaching career he was head of department at a private college in West London. He has written articles and book reviews for the magazine English Teaching Professional and The Huffington Post. His first short story will be published in an anthology entitled Tempest in March 2019.

Peter was recently interviewed for the forthcoming film about the project to fund, create and install a new full-sized bronze statue of Virginia Woolf in Richmond-upon-Thames.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 281

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Ähnliche

Peter Fullagar

Peter Fullagar was raised in Kent and studied for a BA (Hons) in English and Sociology at Anglia Ruskin University in Cambridge, before going on to complete an MA in English Language and Literature at the University of Westminster.

He is a published writer and editor, formerly an English teacher who ventured to work in Tokyo and Moscow. His short stories and articles have been published in anthologies and magazines, including English Teaching Professional as well as The Huffington Post.

He lives in Berkshire with his partner.

www.peterjfullagar.co.uk

First published in the U.K. in 2018 by Aurora Metro Publications Ltd, 67 Grove Avenue, Twickenham, TW1 4HX, UK www.aurorametro.com 02032610000 [email protected]

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Virginia Woolf in Richmond © 2018 Peter Fullagar Editor: Cheryl RobsonCover design © 2018 Scarlett Rickard

With thanks to Angie Thorpe, Ferroccio Viridiani, Piers Shepherd, Ellen Cheshire.

All rights are strictly reserved. For rights enquiries contact the publisher: [email protected].

We have made every effort to ascertain image rights. If you have any information relating to image rights contact [email protected]

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form, or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

In accordance with Section 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, the authors assert their moral rights to be identified as the authors of the above work.

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.ISBN 978-1-912430-03-1

Printed in the UK by T.J. International, Padstow, Cornwall, PL28 8RW

Permissions:

Excerpts from The Diary of Virginia Woolf: Volume I 1915 - 1919 by Virginia Woolf published by The Hogarth Press. Reproduced by permission of The Society of Authors as the Literary Representative of the Estate of Virginia Woolf. ©1977

Excerpts from The Diary Of Virginia Woolf,Volume I 1915 - 1919 by Virginia Woolf edited by Anne Olivier Bell. Diary copyright © 1977 by Quentin Bell and Angelica Garnett. Reprinted by permission of Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company. All rights reserved.

Excerpts from The Diary Of Virginia Woolf, Volume I 1915 - 1919 by Virginia Woolf published by The Hogarth Press. Reproduced by permission of The Random House Group Ltd. ©1977

Excerpts from The Diary of Virginia Woolf: Volume II 1920 – 1924 by Virginia Woolf published by The Hogarth Press. Reproduced by permission of The Random House Group Ltd. ©1978

Excerpts from The Diary of Virginia Woolf: Volume II 1920 – 1924 by Virginia Woolf published by The Hogarth Press. Reproduced by permission of The Society of Authors as the Literary Representative of the Estate of Virginia Woolf. ©1978

Excerpts from Beginning Again: An Autobiography Of The Years 1911-1918. Copyright © 1964 by Leonard Woolf and renewed 1992 by Marjorie T. Parsons. Reprinted by permission of Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company. All rights reserved.

Excerpts from Beginning Again: An Autobiography Of The Years 1911-1918 by Leonard Woolf published by The Hogarth Press. Reproduced by permission of The Random House Group Ltd. ©1964

Excerpts from Beginning Again: An Autobiography Of The Years 1911 - 1918 by Leonard Woolf published by The Hogarth Press. Reproduced by permission of The University of Sussex and The Society of Authors as the Literary Representative of the Estate of Leonard Woolf.

Excerpts from Downhill All The Way: An Autobiography Of The Years 1919-1939. Copyright © 1967 by Leonard Woolf and renewed 1995 by Marjorie T. Parsons. Reprinted by permission of Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company. All rights reserved.

Excerpts from Downhill All The Way: An Autobiography Of The Years 1919-1939 by Leonard Woolf published by The Hogarth Press. Reproduced by permission of The Random House Group Ltd. ©1967

Excerpts from Downhill All The Way: An Autobiography Of The Years 1919-1939 ©1967 by Leonard Woolf published by The Hogarth Press. Reproduced by permission of The University of Sussex and The Society of Authors as the Literary Representative of the Estate of Leonard Woolf.

Excerpts from The Question Of Things Happening: The Letters Of Virginia Woolf: Volume II 1912 - 1922 by Virginia Woolf published by Chatto & Windus. Reproduced by permission of The Random House Group Ltd. ©1976

Excerpts from The Letters Of Virginia Woolf,Volumes II edited by Nigel Nicholson and Joanne Trautmann. Letters copyright© 1976 by Quentin Bell and Angelica Garnett. Reprinted by permission of Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company. All rights reserved.

Excerpts from A Change Of Perspective: The Letters Of Virginia Woolf: Volume III 1923 - 1928 by Virginia Woolf published by Chatto & Windus. Reproduced by permission of The Random House Group Ltd. ©1977

Excerpts from The Letters Of Virginia Woolf, Volumes Ill edited by Nigel Nicholson and Joanne Trautmann. Letters copyright© 1977 by Quentin Bell and Angelica Garnett. Reprinted by permission of Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company. All rights reserved

VIRGINIA WOOLF

in

RICHMOND

written and selected by

Peter Fullagar

Contents

Foreword by Paula Maggio

A Chronology of Virginia Woolf

Introduction

Virginia’s Richmond

The Hogarth Press

Woolf on Writing

Family in the Richmond Era

Virginia and her Servants

Gatherings with Woolf

Health

Photographs

Virginia at her Leisure

Woolf on War

Leonard’s Viewpoint

A Lasting Legacy

Recommended Reading

Endnotes

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank all those who made this book possible, especially The Society of Authors, Sussex University, Penguin Random House and Houghton Mifflin Harcourt for permission to include extracts from the published works of both Virginia and Leonard Woolf.

I’m grateful too for invaluable mentoring from Cheryl Robson at Aurora Metro and to Ferroccio, Angie and Piers for your support and encouragement. Special thanks must go to Paula Maggio for writing the foreword as well as Emma Woolf for her input and inspiration.

Thanks also to my family and friends for your support through the writing of this book, which is dedicated to my father, Gordon Fullagar (1942-2017).

Foreword

by Paula Maggio

Richmond often fails to get the respect it deserves from Virginia Woolf scholars and readers. You won’t find it in the index of Virginia Woolf A to Z by Mark Hussey, the premiere reference book for Woolf scholars. You will hear it characterized as a place Woolf disliked. And if you made a pilgrimage to the very Richmond building where Virginia and Leonard lived the longest – Hogarth House, located at 24 Paradise Road – you may have failed to notice it at all. I made that trip from London on an overcast, rainy day in June 2016, meeting Emma Woolf, great-niece of the literary couple, in a small café across the street from the Richmond train station. Ironically, Virginia’s famous quote used by many food establishments and food writers – ‘One cannot think well, love well, sleep well, if one has not dined well’ – decorated the main wall of the café, suggesting a connection to Virginia but not explaining it. From the café, Emma and I embarked on a brief walking tour of Richmond. When we arrived at Hogarth House, we were chagrined to see that it was suffering from neglect. A thick overgrown vine covered much of the building’s front exterior at the ground level, almost completely obscuring the blue plaque marking it as an historic site where the couple lived from 1915-1924 and where they founded the Hogarth Press. Unpainted plywood covered the main entrance and its sidelights. A large sign with a colorful list of “Site Safety” cautions was prominently affixed to the front door of the Georgian brick home, warning visitors away.

Since then, some things have changed. In the fall of 2017, realtors put a refurbished Hogarth House on the market at a price of £4.4 million, garnering it much publicity as the Woolfs’ former home. Photos showed a pristine entryway set off by four glossy white pillars, with the formerly overgrown vine now neatly trained around windows and along the black wrought iron fence. It no longer obscured the historic blue plaque. Around that same time, a local arts charity, Aurora Metro, began promoting its campaign to erect a life-sized full figure statue of Virginia Woolf seated on a bench on Richmond Riverside and to raise £50,000 to fund its cost. Fittingly, the piece by acclaimed sculptor Laury Dizengremel is meant to recognize the ten years Virginia spent in Richmond.

Dizengremel’s sculpture also pays homage to the work Virginia completed there, as well as Richmond’s appearance in her later fiction. While living in Richmond, Virginia wrote countless reviews and essays, along with such fiction as Two Stories (1917), Kew Gardens (1919), Night and Day (1919), Monday or Tuesday (1921), and Jacob’s Room (1922). Richmond also figured as a location in her later writing as well.

Virginia Woolf in Richmond by Peter Fullagar, is a timely companion piece to this recent recognition – of Richmond in general and Hogarth House in particular – as locations important to Virginia and her writing. As a writer and editor who is a member of the Virginia Woolf statue campaign and someone who has reported on the effort for HuffPost UK, Fullagar is ideally positioned to make the case for Richmond’s importance in Virginia’s life and work. He does just that in Virginia Woolf in Richmond, providing a comprehensive analysis of the time Virginia spent in the suburb, a mere fifteen-minute train ride from central London. By mining Virginia’s diaries and letters – rich resources always ready to reveal new insights into her inner and outer life as well as her work – Fullagar explores how living in the town influenced Virginia’s life and her development as a writer.

He starts out by putting the lie to the negative quote about Richmond attributed to Virginia in the 2002 film The Hours, based on Michael Cunningham’s 1998 novel by the same title. Fullagar shows us that discerning Virginia’s true feelings about Richmond requires that one explore quotes garnered from her personal work. He leads us on that journey, quoting from Virginia’s diaries and letters to convey her feelings – overwhelmingly positive – about Richmond itself, Hogarth House in particular, and living, working, and writing in Richmond, whose ‘simplicities and refinements’ she extolled in a 5 February 1921 letter to Violet Dickinson.

Drawing from her personal writing, Fullagar describes Virginia’s life in the community – from her work with the Women’s Co-operative Guild to her efforts to set up a bread shop to her long walks around town and country. Her 23 January 1918 diary entry, which Fullagar includes, aptly conveys her positive feelings about the Richmond countryside: ‘We have glimpses of Heaven. So mild that the landing window is open, and I sat by the river watching a boat launched, and half expected to see buds on the willows’. Virginia was inordinately fond of Hogarth House, which the Woolfs made their home from March of 1915 through March of 1924. In her letters and diaries, she describes it as ‘a perfect house, if ever there was one,’ ‘far the nicest house in England’, and a ‘beautiful and lovable house, which has done us such a good turn for almost precisely nine years’.

While biographies of Virginia recount the factual details of Hogarth Press history, this book does more. It explores the challenges and joys the Woolfs experienced in their day-to-day operations of the press. By quoting Virginia’s diaries and letters, as well as Leonard’s multi-volume autobiography, Fullagar conveys the couple’s feelings about their endeavor over the years, from the Hogarth Press’s ‘very awkward beginning . . . in this very room, on this very green carpet’, to its beanstalk-like growth, to its 1924 stature as a well-established and successful literary and commercial enterprise that had printed about 32 books during its years in Richmond.

Virginia Woolf in Richmond doesn’t stop with the Hogarth Press. It goes on to mine Virginia’s diaries and letters to help us understand her views on and experiences with writing, servants, family, leisure, and the Great War during the ten years she spent in Richmond. Scholars recognize the fact that the diaries and letters Virginia left behind are extraordinary resources that provide us with much territory still to explore on many topics. What Fullagar does in this book is give Virginia’s years in Richmond their due. By carefully focusing on Virginia’s own words written during that time period, he successfully argues that living in Richmond was an important and positive experience for this twentieth-century writer by showing how Richmond shaped Virginia’s life and work. Including Leonard’s thoughts about that time in their life reinforces its value. Indeed, Fullagar makes the case that Virginia left a rich and lasting literary legacy for Richmond, one that has yet to be duly recognized.

This book, published in association with the campaign to erect the first, full figure, life-size bronze statue of Virginia Woolf in Richmond, in celebration of the ten years that Virginia and Leonard lived there, gives recognition of that legacy a well-deserved boost.

“I ought to be grateful to Richmond & Hogarth,and indeed, whether it’s my invincible optimism or not, I am grateful.”

– Virginia Woolf

Chronology

1878 Leslie Stephen and Julia Duckworth marriage.

1879 [30 May] Vanessa Stephen born.

1880 [8 September] Julian Thoby Stephen born. [25 November] Leonard Woolf born.

1882 [25 January] Adeline Virginia Stephen born.

1883 [27 October] Adrian Leslie Stephen born.

1895 [5 May] Julia Stephen dies. Virginia has first breakdown.

1897 [10 April] Half-sister Stella Duckworth marriage. [19 July] Stella dies.

1904 [22 February] Leslie Stephen dies. Virginia’s second breakdown. Stephen siblings move to 46 Gordon Square, Bloomsbury.

[October] Leonard Woolf moves to Ceylon to work for Ceylon Civil Service.

1905 Beginning meetings of ‘The Bloomsbury Group’.

1906 [September] Vanessa and Thoby ill on return from Greece.

[20 November] Thoby dies. [22 November] Vanessa agrees to marry Clive Bell.

1907 [7 February] Vanessa and Clive Bell marriage.

[April] Virginia and Adrian move to 29 Fitzroy Square.

1908 [4 February] Son of Vanessa, Julian Bell born.

1909 [17 February] Lytton Strachey proposes to Virginia, but retracts.

1910 [10 August] Son of Vanessa, Quentin Bell born.

1911 [May] Leonard Woolf returns from Ceylon on leave. Virginia moves to 38 Brunswick Square with Adrian, Duncan Grant, Maynard Keynes and Leonard Woolf.

1912 [January] Leonard proposes to Virginia.

[February to March] Virginia has period of mental instability. [20 May] Leonard Woolf resigns from Civil Service.

[29 May] Virginia accepts Leonard’s proposal. [10 August] Virginia and Leonard Woolf marriage.

1913 Virginia has serious breakdown in summer. [9 September] Virginia attempts suicide.

1914 [4 August] War declared. [16 October] Virginia and Leonard rent rooms at 17 The Green, Richmond. Virginia and Leonard view Hogarth House towards the end of the year.

1915 [March] Leonard acquires lease for Hogarth House;

Virginia’s mental health deteriorates; The Voyage Out published.

1917 [April] Printing press arrives at Hogarth House. Two Stories published by Virginia and Leonard.

1918 [11 November] Armistice Day. [25 December] Daughter of Vanessa, Angelica Bell, born.

1919 [May] Kew Gardens published by Hogarth Press.

[1 September] Virginia and Leonard take possession of Monk’s House, Rodmell. [October] Night and Day published.

1922 [October] Jacob’s Room published.

1924 [March] Virginia and Leonard move from Hogarth House to 52 Tavistock Square.

1925 [April] The Common Reader published. [May] Mrs Dalloway published.

1927 [May] To the Lighthouse published.

1928 [October] Orlando published. Virginia speaks at women’s colleges in Cambridge.

1929 [October] A Room of One’s Own published.

1931 [October] The Waves published.

1932 [21 January] Death of Lytton Strachey.

1933 [October] Flush published.

1934 [9 September] Death of Roger Fry.

1936 [April] After finishing The Years, Virginia collapses.

1937 [March] The Years published. [18 July] Death of Julian Bell.

1938 [June] Three Guineas published.

1939 [3 September] War on Germany declared.

1940 [July] Roger Fry: A Biography published.

1941 Between the Acts finished. [March] Virginia

becomes ill.

[28 March] Virginia drowns herself in River Ouse. [18 April] Virginia’s body found. [21 April] Virginia Woolf cremated.

1953 A Writer’s Diary published.

1961 [7 April] Death of Vanessa Bell.

1969 [14 August] Death of Leonard Woolf.

1975 First edition of Letters of Virginia Woolf published; 6 volumes, 1975-1980.

1976 Moments of Being published.

1977 First edition of The Diary of Virginia Woolf published; 5 volumes, 1977-1984.

2017 The Hogarth Press celebrates centenary with publication of Two Stories by Virginia Woolf and Mark Haddon.

Introduction

All the rooms, even when we first saw them in the dirty, dusty desolation of an empty house, had beauty, repose, peace and yet life.

− Leonard Woolf

Why Richmond?

Virginia Woolf, aged 32, was an aspiring writer who had recently completed her first novel when she moved to Richmond, in south-west London. Leonard Woolf, her husband, wanted to find somewhere quiet where Virginia could fully recover her mental health, as the strain of writing her debut novel, The Voyage Out had led to mental exhaustion and collapse. Central London was considered too busy, too full of distractions and social gatherings that could be detrimental to Virginia’s fragile state of mind, and so after considering Hampstead and Twickenham, Richmond was chosen as the ideal place for Virginia to reside. It was also close to the nursing home, Burley House, in Twickenham, where Virginia had been confined during her recent illness.

In October 1914, the couple first moved to a lodging house on The Green in Richmond. The Woolfs were pacifists and opposed to the war with Germany, but the reality of the conflict would have been inescapable, due to the large military presence in the town, with regular drills carried out at 8pm every evening on Richmond Green right opposite their lodgings. The town’s small population swelled with hundreds of Belgian refugees and troops moving through the town to the Front.

While renting rooms with their Belgian landlady, Mrs le Grys at 17 The Green, the couple spotted Hogarth House, which was only a few minutes’ walk away along Paradise Road. The Woolfs immediately fell in love with Hogarth House and set about acquiring it. They moved into the house in 1915, albeit under the dark shadow of Virginia’s struggle to get well and the on-going stress of what was referred to initially as the ‘European Crisis’. People had hoped the war would be over quickly but the food rationing and mounting number of casualties led to widespread distress. There was a Relief Committee to help those who were unemployed or widowed, while wounded soldiers were returning in large numbers to be nursed in Richmond Hospital and the military hospital which was created at the Star and Garter hotel. By May 1915, when the first Zeppelin airship bombing raids began over central London, the Third Battalion Signallers from the London Scottish Regiment were encamped in Richmond Park. In 1916, a new military hospital for South African soldiers was being built to house the hundreds of wounded survivors being transported to the town.

Through her diaries and letters, the reader can see how the war affected daily life, as Virginia describes the effects of the numerous air raids in and around London. For example, towards the end of the war in March 1918, Virginia writes:

‘…the guns went off all round us and we heard the whistles. There was no denying it.’1

We get a glimpse into how people at that time coped with the ferocity of the war, by hiding and sleeping in cellars and kitchens. Virginia and Leonard were no different; mattresses were laid down in lower rooms and the time was spent with the servants, Nellie and Lottie. Through this time, Virginia was extremely worried about the safety of her sister Vanessa and her friend, Katherine (Ka) Cox, but everyday life continued despite this – visitors were still received at the house and writing continued. The war was a time of great anxiety for the Woolfs. It would later permeate Virginia’s writing, most notably in Jacob’s Room and Mrs Dalloway, started in January 1920 and mid-1922, as The Hours, respectively. Jacob’s Room follows Jacob through his life in Cambridge, London and Greece, places that Virginia had visited. Although not directly referencing the war, the first lines of the novel give a great indication:

‘So of course,” wrote Betty Flanders, pressing her heels rather deeper in the sand, “there was nothing for it but to leave.”’.2

One of the most well-known poems of the war was written in 1915 by John McCrae, entitled In Flanders Fields, and, as some critics have noted, Flanders can be seen as a synonym for death in battle. There is an obvious connection between the character of Jacob and Virginia’s deceased brother, Thoby, who died in 1906 aged 25, and it has been suggested that Jacob’s Room was written not only as an elegy to him, but also to the countless numbers of young men killed in the Great War.

Today, Richmond is fortunate that the buildings at 17 The Green and Hogarth House still stand. They are both Grade II listed as historic buildings, meaning that they are of special interest and every attempt should be made to preserve them. Both properties have recently been renovated. Hogarth House has been graced with a blue plaque that testifies to the years the couple spent there and their creation of The Hogarth Press. Richmond Green remains largely as it was a century ago but Paradise Road is now a busy thoroughfare with regular traffic queues and Hogarth House is surrounded by office buildings and a public car park, but it isn’t hard to imagine Virginia watching the army trucks and soldiers on horseback passing along the street a hundred years ago. Being located close to the shops and only five minutes away from the station, the couple were able to easily travel by train to visit friends and family living elsewhere. The house is also close to the River Thames and to the semi-wilderness of the ancient Deer Park at the top of Richmond Hill, which offered the couple many opportunities for delightful walks in the area. Indeed, going for long walks was advised by Virginia’s doctors, and Virginia seemed to enjoy walking around the Richmond area, often wandering to Kew Gardens with her dogs, casually observing all manner of life and activity around her.

In her writing, Virginia presents Hogarth House as a solid building, with thick walls and doors, almost like a protective shroud. Leonard also refers to Hogarth House as ‘graceful and light’, demonstrating that the couple thought of the house not only as a safe haven, but also as a comfortable home. It was, indeed, ‘…a perfect envelope for everyday life.’3

Her first novel, The Voyage Out, had received warm reviews, and Virginia was determined to make a name for herself in the literary world. The time she spent living in Hogarth House, could be described as an embryonic period for her development as a novelist, which was to be further enhanced by the creation of the Hogarth Press.

The Hogarth Press

The Hogarth Press began as a hobby for Leonard and Virginia. In fact, Leonard had decided that it would be useful for Virginia to have something practical to focus on, as her writing and self-absorption took such a toll on her mental health. She needed a distraction from the psychological strain of writing which brought with it the anxiety of never being able to make a name for herself as a respected writer.

Having relocated to the suburbs to escape the constant demands of Bloomsbury’s hectic social scene, Leonard believed he had found the perfect place for Virginia to recover and settle down to a regular routine. In his autobiography, Beginning Again, Leonard describes the moment that the couple saw a printing press in a shop window:

‘We stared through the window at them rather like two hungry children gazing at buns and cakes in a baker shop window.’4

They attempted to learn the process of printing, but eventually bought a press which came with an instruction manual and they taught themselves from there. Although it was initially a struggle with some setbacks, the couple persisted in their aim to be able to publish their own work and the process of printing and publishing became a source of great joy and pride for both of them.

At the time when their new press was delivered, Virginia was not writing regularly in her diary, but she was sending frequent letters to family and friends. She describes the new arrival with great excitement, but also describes the difficulties with the typesetting process. In a letter to her sister, Vanessa Bell, on April 17th 1917, she says that, ‘…the arrangement of the type is such a business that we shan’t be ready to start printing directly.’5

She goes on to describe how the large blocks of type would need to be split into separate letters and fonts, which then have to be placed into the correct partitions. Unfortunately for Virginia, soon after starting, she confused the h’s with the n’s, leading them to start the process of typesetting all over again.

In a later letter, she describes Leonard’s feeling of never wanting to do anything else but printing and it seems that Virginia is very happy at this particular moment. Their first attempt at producing fiction was in 1917 when they decided to print a short pamphlet which contained two stories; one each by Virginia and Leonard.

Two Stories was officially published in July of the same year and included Three Jews by Leonard and The Mark on the Wall by Virginia. The pamphlet was around 34 pages long but took the couple more than two months to produce due to the lengthy process of setting the type manually.

The couple had decided that they would publish other authors too, and their second endeavour was Prelude by Katherine Mansfield in 1918, followed by Virginia’s short story Kew Gardens and T.S. Eliot’s collected Poems in 1919. These first four publications were printed and bound by the Woolfs themselves, but this was not the case for all the publications that followed. In the first four years of the Hogarth Press, the Woolfs had published nine books. It is worth noting the earnings from these books, as laid out in Leonard’s autobiography, Beginning Again6:

.

Two Stories £7 1s. 0d.

Prelude £7 11s. 8d.

Kew Gardens £14 10s. 0d. Eliot’s Poems £9 6s. 10s. Murry’s Critic in

Judgment £2 7s. 0d.

Forster’s

Story of the Siren £4 3s. 7d.

Mirrlees’s Paris £8 2s. 9d.

Stories from the

Old Testament £11 4s.5d.

Gorky’s

Reminiscences £26 10s. 9d.

With total expenditure amounting to around £38, the total net profit at the end of the first four years was around £90. The couple also paid the author 25 per cent of the gross profits and had to include printing costs when they didn’t print and bind the book themselves. What seems incredible, is that even with Virginia’s fragile health, leaning on great support from Leonard, they were able to start a small publishing business with no capital. Leonard himself expresses surprise at this fact, and that ‘…ten years after…the Hogarth Press was a successful commercial publishing business.’

From the publication of Jacob’s Room in 1922, Virginia decided that she would not write for other publishers again:

‘A 2nd edition of the Voyage Out needed; and another of Night and Day shortly; and Nisbet offers me £100 for a book. Oh dear there must be an end of this! Never write for publishers again anyhow.’8

Accordingly, all her subsequent work was published by the Hogarth Press. Leonard describes this decision as arising from Virginia’s hypersensitivity to criticism, and that publishing her own works without having to suffer the negativity of sending manuscripts to publishers for scrutiny, filled her with delight.9

By 1917, the couple were at the centre of a group of emerging writers who wanted to look at the world with fresh eyes. Europe was still in the deadly throes of the Great War which had blighted an entire generation. In Russia, the Tsarist regime had been replaced by a new government, which was overthrown in October by Lenin’s Bolsheviks. Leonard Woolf had socialist sympathies and would have understood the importance for workers to control the means of production. He would also likely have known of William Morris’ small press, the Kelmscott Press, which published over fifty works in the 1890s, with many books including illustrations by Edward Burne-Jones. This may well have provided a model for their own small press enterprise and their choice to involve Virginia’s sister, Vanessa Bell, to design the covers for the books.

This ownership of the means of book production gave both Leonard and Virginia the autonomy to be able to decide their own work schedule; it gave them editorial and artistic freedom too. It could be argued that the facility of the Hogarth Press saved Virginia from further mental instability caused by the demands of outside editors and publishers. As she writes in her diary, before leaving Richmond on January 9th 1924:

‘Moreover, nowhere else could we have started the Hogarth Press, whose very awkward beginning had rise in this very room, on this very green carpet.’

The slower pace of life in Richmond was clearly beneficial for Virginia too, both for her writing career and her mental health. Apart from the artistic control which the Hogarth Press gave to the couple, it also gave them a measure of financial security too; by April 1938, Virginia writes:

‘Press worth £10,000 and all this sprung from that type on the drawing room table at Hogarth House 20 years ago.’10

Becoming a Writer

Living in Richmond from 1914 to 1924 was a prolific time for Virginia, the writer. As well as countless essays, reviews and stories, including Mr Bennett and Mrs Brown, Kew Gardens and The War from the Street, she completed and published Night and Day, Monday or Tuesday and Jacob’s Room, which, as she mentions in a letter to Philip Morrell in 1938, she describes as her favourite novel. In addition to working on these, during this time period she was also writing The Common Reader and Mrs Dalloway, which were both published in 1925, a year after leaving Richmond.

In a diary entry in March 1927, Virginia writes; ‘So I made up Jacob’s Room looking at the fire at Hogarth House.’ It is no surprise that she was looking at the fire while creating a novel. Virginia’s way of writing has been described in great detail by Leonard in his autobiography. Rarely using her writing room to actually write her novels, she would sit in an armchair with a piece of plywood on her knees, upon which she had glued an inkstand11. This, according to Leonard, was the way in which she wrote the first drafts of all her novels. While writing, she was completely ensconced in her work, or as Leonard calls it ‘writing with concentrated passion’. One can imagine Virginia, sitting by the fire in Hogarth House, furiously working away on one of her novels.

Leonard describes two stages of passion and excitement when Virginia was working on a novel; the first, being the creation or actual writing, during which she would be most concentrated. The second occurred when she was going to send the manuscript to the printers – he called it a ‘passion of despair’12, and it is from this stage that she was most vulnerable to a breakdown. Leonard had witnessed this in 1913 just after she had finished The Voyage Out. Again in 1941, Virginia succumbed to this ‘passion of despair’ after finishing Between the Acts and it was this and other factors including the horrors of the Second World War that contributed to her taking her own life a few months later, by drowning in the River Ouse near their Sussex home, Monk’s House.

Through her diaries, it is clear that she enjoyed writing Jacob’s Room, calling it the most amusing novel she had worked on. Aside from the usual falls in confidence, especially with the form of the novel, Virginia found that Jacob’s Room, although an experiment, left her with an elevated sense of herself, as she writes in her diary: ‘There’s no doubt in my mind that I have found out how to begin (at 40) to say something in my own voice.’

Jacob’s Room was considered to be Woolf’s first experi-mental novel, with critics calling it her first mature work. The narrative is not conventional, but flows from moment to moment, rather like a stream of consciousness. From the diary quote above, it seems that Virginia had finally found the voice that she wanted to present, and this discovery of her writer’s voice had its beginnings in Richmond. The writing of Night and Day, completed earlier than Jacob’s Room, seems to have been easier (and certainly was in comparison to the numerous drafts of The Voyage Out).

Published in 1919, Night and Day follows the romantic lives of two women, Katherine and Mary and reflects the debate about love and marriage that was current at the time. Mary works for a suffrage organisation and although some women had been granted the right to vote in 1918, there was an on-going campaign for all women to be granted suffrage which continued until universal suffrage was finally granted in 1928.

During the First World War, many women left their homes and entered the work place, taking on roles vacated by men who were then on the front line. As the men returned, some women were reluctant to go back to their previous domestic roles. This caused a lively discussion in the press and in society about ‘women wanting to wear the trousers’.

Virginia considered Night and Day as a development of her work from The Voyage Out, as well as having more depth and eschewing a neat resolution. One of her characters, Mary, in Night and Day,