Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Atlantic Books

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

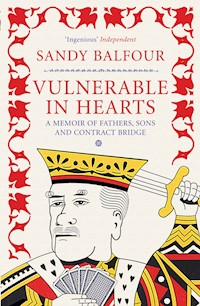

Sandy Balfour's father and the game of contract bridge were both conceived in 1925. Vulnerable in Hearts spans the eight decades of Tom Balfour's life and the same period in the epic story of bridge's spread around the world. Sandy Balfour's poignant and beguiling book traces both journeys to explore the relationships between a game and an empire (and the rules that supported it); and a father and a son.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 301

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

VULNERABLE IN HEARTS

Sandy Balfour was born in South Africa and emigrated to Britain in 1983. He is an award-winning television producer and the author of the acclaimed Pretty Girl in Crimson Rose (8): A memoir of love, exile and crosswords.

‘A rich book... Bridge has had a long and colourful history, which Balfour takes and gives much pleasure in recalling.’ Ronald Segal, Spectator

‘For the Balfours, bridge was both a passion and a rich source of catch phrases. Yet its strange rituals and terminology – penalty cards, takeout doubles, forcing passes and the crucial notion of “vulnerability” – also give Sandy an ingenious way of talking about the emotional undercurrents and communication styles in his family. Vulnerable in Hearts interweaves the story of a bridge obsessive with an account of the development of a game which happens to have acquired its definitive form in 1925, the year Tom was conceived. It explores grief, nostalgia and other painful feelings with great simplicity and candour. And it is full of sharp detail, whether of Tom’s physical presence, different styles of dealing, even the photos from girlie magazines and handprints in human ash on the walls in the back room of the crematoriums ... Even bridge virgins should enjoy the lively anecdotes about its history.’ Matthew J. Reisz, Independent

Also by Sandy Balfour:

Pretty Girl in Crimson Rose (8): A memoir of love, exile and crosswords

for my brother

First published in Great Britain in 2005 by Atlantic Books,an imprint of Grove Atlantic Ltd.

This revised paperback edition published by Atlantic Books in 2006.

Copyright © Sandy Balfour 2005

The moral right of Sandy Balfour to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

Every effort has been made to contact copyright holders. The publishers will be pleased to make good any omissions or rectify any mistakes brought to their attention at the earliest opportunity.

9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 78239 373 3

Design by Lindsay Nash

Atlantic Books An imprint of Grove Atlantic Ltd Ormond House 26–27 Boswell Street London WC1N 3JZ

The sights and sounds of my youth pursue me; and I see like a vision the youth of my father, and of his father, and the whole stream of lives flowing down there far in the north, with the sound of laughter and tears ...

R.L. Stevenson, from the dedication to Catriona

Contents

PART I ONE DAY IN JANUARY

1 Shuffling

2 Brothers-in-arms

3 Voices

PART II WHEN MY WORLD WAS YOUNG

4 Walking on the moon

5 Latitudes

6 Daft at cards

7 Capsizing an Optimist

8 Welcome to our world

9 Falling in, falling out

10 A house of cards

11 People not cards

PART III WHEN HIS WORLD WAS YOUNG

12 An evening in Panama

13 Travels with Cal

14 Remembering everything

15 Man bites dog

16 The man who made contract bridge

17 The square yard of freedom

18 The game goes global

19 Bloody Culbertson

20 Freetown

21 Second-generation bridge

22 A brief war

PART IV A VALEDICTION FORBIDDING MOURNING

23 The far side

24 Coming and going

25 A tour of duty

26 For the record

Acknowledgements

PART I

ONE DAY IN JANUARY

1. Shuffling

WE WERE A family of five, which is the perfect number for bridge. Four to play and one to make tea. I say ‘were’ because Dad is no longer with us. He died with a void in diamonds and a hole in his heart and, though I loved him dearly, I sometimes thought I hardly knew him. He died quietly and not quite alone in a hospital in Durban in the summer of 2003. He was angry and sad and he made me smile. When he laughed his whole body shook. It would start with his shoulders. They would heave up and down like a threshing machine. Then it would spread to his stomach and his cheeks. His jowls waggled like an old bulldog, while his bony knees knocked together like castanets. His laugh could fill a room or a hall or a young boy’s world until a coughing fit caught up with him and he would turn puce and hawk and spit to clear his throat of tobacco-stained phlegm. Even now people speak of it. It made us giggle and reduced him to tears.

I saw a lot of him in his last few days. He was in a hospital in Durban in a room that looked over the bay. There were container ships out to sea and a breeze in the trees. We talked a lot too, more than in the twenty years since I left South Africa. There was nothing else to do. He couldn’t move, and I couldn’t budge. I felt bolted to the chair beside his hospital bed and I spent the hours watching the life ebb and flow in his strange, depleted white body. Some days he was tired; others he seemed stronger. Our conversations were as they had always been, coded, cautious and full of silences. They were like the bidding in bridge. Few words were needed, and those we used took on different meanings depending on when they were said and by whom. He said dying was sad only for those who insist on living. He asked whether it was cold, or was it just him? He said he had nothing to say and that he wanted to shave. He wished his bloody hands would stop shaking.

I said I was sorry.

He said to give his regards to the kids – my kids, his grandchildren.

‘Just regards?’ I asked.

‘Aye,’ he said. ‘The rest they’ll get from you.’

I wondered what the rest was. When I asked if he had any regrets, he made what in bridge is sometimes called a ‘forcing pass’. It required a response from his partner, although exactly what this response should be would have depended on the partnership understanding and on what the others at the table might have to say for themselves. Often a forcing pass comes into play when one or other pair at the bridge table is about to or has the opportunity to make a ‘sacrifice bid’. A sacrifice bid means that the partnership reaches a contract which it knows it is unlikely to succeed in making, but which it anticipates will be less expensive than allowing the opponents to make a rival contract. The scoring in bridge works that way. If you make a vulnerable contract of four spades, it’s worth 620 points to you. And nothing to your opponents. If they’re not vulnerable, they might decide to bid five clubs even though they know they’re unlikely to make it. Because, even if they fall three short of the required number of tricks, it will cost them only 150 points. They lose – but, relatively speaking, they win. Partners playing the forcing pass sometimes have to guess. Should I bid or shouldn’t I? And, if so, what? I knew that I would have to decide the question of Dad’s regrets for myself.

At least he was glad to hear I was playing bridge again. He thought it would do me good. He’d been playing a bit with a bunch of grumpy old men from the local club. Each afternoon they would meet in a different house. Their wives would put out sandwiches and tea and go to the movies. But they’d play in silence and it wasn’t much fun. In the last couple of years, he had more or less given it up. Pity, in a way, but what could you do? If it wasn’t fun, there wasn’t much point, not even to keep Alzheimer’s at bay.

‘Do you remember actually learning the game?’ I asked.

‘No, not in any detail.’

Detail was important to Dad. He liked things to be precise. He liked mathematics.

‘Everyone has to learn somewhere,’ I suggested.

‘Sure,’ he said, shrugging.

I told him I had read somewhere a story about Omar Sharif. Sharif is almost as famous for his bridge as he is for his movies. In one interview, he said that he learned bridge while relaxing on a movie set in Egypt in 1954. ‘I found myself with a lot of spare time waiting for the cameras to be ready. I found a dusty old book and read it. It happened to be about bridge. Had it been about fishing or gardening, I would have been a healthier, outdoor, tanned old man,’ he said.

Dad supposed he had learned bridge from his parents back when they lived in Edinburgh. Come to think of it, he was sure he had.

‘It would have been Pa that taught me,’ he said, ‘although Ma wasn’t so bad herself.’

‘A bit like you and Mum,’ I suggested.

But Dad was lost in a reverie that sped him back across the decades to Edinburgh. That’s where he grew up, in a house on a hill in the south of the city. This was in the late thirties, when bridge was at its most popular. His dad was a bank clerk and his mother a teacher. It would have been strange if they hadn’t taught him bridge.

‘Aye, but it was Uncle Willie made me love it,’ he said.

Dad remembered that his uncle Willie played until old age. He had lived in the Borders someplace, in Scotland, and suffered from Parkinson’s disease. His eyes shone and his hands shook. When he came to stay they would play through the night. Willie had been gassed in the trenches during the Great War. Dad said he kept everyone awake with his coughing. The next morning he’d put them to sleep with his analysis of the play. When he could no longer keep thirteen cards in his hands, his brothers built a special wooden rack to hold them.

I wondered what happened to the rack. Dad asked why it mattered. I said because things do and he said perhaps. He said it was a pity we couldn’t play. He would have liked to beat me one more time.

‘But we always played together,’ I whispered.

‘Och, aye,’ he said. ‘Boys against girls.’ He and I were the ‘boys’. My mother and sister, Jackie, were the ‘girls’. Sometimes thinking (erroneously, as it happens) that I was better than Jackie (and certain, it goes without saying, that he was better than Mum), Dad would mix us up a little, which is to say I would play with Mum and he with Jackie. But this arrangement never quite worked. There was no edge to it and we all played worse as a result. The former plan was better. They may have got all the points, but we got all the glory, and in Dad’s mind the pursuit of points was as nothing compared to the pursuit of glory.

‘So how could you beat me?’ I asked. ‘We were partners.’

But he passed again, which was my punishment for being too bloody literal. And, besides, it is not unknown at the bridge table for players to treat their partners even more brutally than their opponents. Zia Mahmood, one of the great players of the modern generation, writes (approvingly, by the way) of a particular player who frequents the New York bridge club scene and who ‘played what I call “Israeli Savage”, an aggressive version of “Paki Savage”. Basically, the system has two rules: 1) Bid no trump and 2) punish your partner and your opponents alike without mercy.’ Mahmood comes from Pakistan, though he now plays for the United States, and is a keen advocate of what he calls ‘Paki Savage’, an unbridled style of bidding intended to make life extremely difficult for your opponents. And if your partner can’t keep up? Well, that’s his problem.

Dad smiled at my discomfort, which must have hurt like hell. He wanted to laugh but his body couldn’t take it. Even the smallest movement pulled at the stitches from the operation to clear the cancerous blockage in his throat. He winced and closed his eyes, which was how he disguised his pain. I could see he was drifting off. It was time to go. He held my hand a moment.

‘You can still play,’ he said. ‘You’ll have David.’

David is my elder brother.

‘He doesn’t play,’ I said. ‘He doesn’t like the game.’

‘Och, ja, so he says.’ My father is the only person I have known to say ja with an Edinburgh lilt.

‘It’s true, he doesn’t.’

David is a scientist, a botanist and an ecologist. For many years he has lived and worked in South Africa’s game reserves. His fingers are scarred from working in the bush. He is tall, tanned and muscular. There is rhino dung under his nails and he smells vaguely of diesel. He doesn’t look like a bridge player and he doesn’t want to be one. If he were on a movie set and found a book about bridge, he would use it to prop up his wobbly workbench. Despite his upbringing, despite his father, despite everything, David has never shown any interest in bridge. Not a glimmer. Once, when asked to play, he said he would rather bathe in soggy lettuce, a vegetable to which he at that time had a near-pathological aversion.

‘Everyone likes bridge,’ Dad said. ‘They just don’t know it yet.’

2. Brothers-in-arms

DAVID DOESN’T EAT meat and I don’t drink alcohol, but this morning we’re doing both. Beyond the bougainvillea-laden fringe of the veranda where we sit, the sun drips on to a dappled lawn. There have been night rains and the air is clean and fresh and for the moment it is almost cool. There is enough cloud to suggest that it might rain again, but for now tendrils of steam rise from the leaves and grass and a slight breeze caresses the leaves of the jacaranda trees that line the driveway. A cat stretches out on the windowsill.

We’ve gone for the works. ‘Everything,’ David said to the waiter. ‘Eggs, bacon, sausage, mushroom, beans, maybe a bit of steak? Toast, hash browns, I don’t know. Bring us everything you’ve got. Maybe put some cheese on that steak.’

‘And champagne,’ I added. ‘Your most expensive. And orange juice and coffee and maybe a little fruit salad.’

‘With ice cream,’ says David.

The waiter looks at us and starts from the top.

‘Eggs for two?’

‘Please.’

‘Scrambled or fried?’

‘Scrambled,’ I say. David prefers his fried.

‘And sausage?’

‘Ja.’

‘Also for two.’

We’re laughing now and the waiter is beginning to relax a little. After all, it is late for breakfast, a little after eleven in the morning, and we are the only customers in the restaurant.

‘Mushroom, beans, toast, steak. Everything,’ David says.

‘And champagne,’ I repeat.

‘The most expensive?’ says the waiter with the trace of a grin.

‘You got it. Two bottles.’

‘Two bottles?’ He looks at me and then slowly begins to write. ‘2 btle Chmp.’

‘But don’t open them, OK. I think we should open them. And cold please.’ I turn to my brother. ‘I can’t drink the stuff unless it’s really cold.’

‘OK,’ says the waiter. He looks at the list on his pad. ‘You want the fruit salad first or last.’

‘Together,’ says David. ‘Except the champagne. We want that first.’

‘And maybe the ice cream. Bring the ice cream and the champagne first.’

Eventually the waiter is confident that he has our order. As he disappears through the large French doors that open on to the veranda where we’re sitting, he casts one last backward glance at us as if he thinks we might make a run for it the moment he is out of sight. There’s something not quite right about these two middle-aged men behaving like schoolboys at this hour of the morning. And so well dressed?

It doesn’t add up, but it’s true. We are well dressed. I’m wearing a suit and dark tie, and a new white shirt. The gleam of my polished shoes mirrors my shiny face because for once I am freshly shaven. David, of course, isn’t. It must be twenty years since he was last clean-shaven and probably longer since he last wore a tie. But by his standards he looks quite respectable. His cotton shirt is neatly pressed and his trousers have a crease. He has even polished his shoes. He got married a decade ago, so maybe it’s only ten years since he last polished his shoes.

We look at each other; there is not much to say, but slowly the hint of a smile begins to form around the corner of his mouth, and I can feel mine starting too. Once we start to giggle, there’s no stopping us. Holding our sides, lying face down on the table, we laugh until we cry, and then we laugh some more. Our shoulders shake, but only moderately.

‘Oh, Christ,’ I say, ‘the porn!’

‘Jesus, I’ll never forget those bloody pictures. Did you see Mum’s face?’

‘And the handprints on the wall? Must have been ash!’

And we laugh again at the thought of Mum’s face, and the porn and the handprints of the ashes of the dead on the wall, even though the porn wasn’t hardcore, just the centrefolds from Scope magazine, South Africa’s equivalent of ‘Page Three Girls’.

‘Oh, dear God.’

But after a while the laughter can’t sustain itself, and we sit up a little straighter and look back to the French doors.

‘I hope I never have to do that again,’ I say.

‘You won’t,’ says David.

It takes me a moment to work out the truth of this statement. Just then the woman who owns the restaurant comes through the French doors. She is carrying a silver tray with a bottle of champagne, a carafe of orange juice and two bowls of vanilla ice cream.

‘So howzit, gents?’ she says in a South African accent so strong that if I had heard it in London it would have sent shivers down my spine. But here in Hillcrest, KwaZulu-Natal, on this warm summer’s day with a hoopoe on the lawn and a purple-crested loerie in the avocado tree, it sounds just about right. It is warm and throaty, filled with the sound of sun and cigarettes and the evening dop. ‘What’s the celebration?’

David is busy with the champagne bottle and so it falls to me to answer. ‘You don’t want to know,’ I say.

‘Ah, come on,’ she replies, ‘don’t keep it to yourselves.’

She’s maybe our age, maybe a little older, maybe quite a bit older, when I look too closely. I guess she’s fifty, which makes her ten years older than me, seven more than David. She’s not unattractive, here in the subdued light of a cool veranda in a quiet commuter suburb twenty miles inland from Durban. She’s wearing a loose terracotta skirt and a white blouse. Her eyes are blue and her hair – for today at least – is auburn. It’s not hard to imagine her story. The marriage, the kids, the divorce. No doubt the divorce was delayed long enough for the kids to grow up, go to university, leave home. Then came the settlement that meant she could buy the restaurant. Her finger has the shadow of a ring. Perhaps she took it off for us.

She eyes us up and begins to flirt a little. I notice that she is even in her favours. Neither of us wears a ring. Perhaps she’s wondering which of us is older because, although I look it, David has a quiet authority about him. And anyway he’s better looking than me, despite the beard. Without it, he looks a lot like Dad. He has the same long, thin face and deep-set eyes, the same high cheekbones and caterpillar eyebrows. They’re both tall and thin, although David is not exceptionally so. Unlike Dad, he can stand against a window and still be seen. Light doesn’t refract around him.

‘You look a lot like him,’ I say.

‘It could be worse,’ he says. ‘I could sound like him.’

‘Like you,’ he adds, in case I’ve missed the point. The cork pops and David pours the champagne.

‘You’d better get yourself a glass,’ I say to the owner.

At first she demurs. ‘It’s your party, gents. Enjoy.’ But under a little pressure she begins to relent. There’s some bargaining to be done first. ‘I need to know what I’m drinking to,’ she says, as she sends the waiter off to fetch another champagne flute and takes a seat at our table.

David pours her champagne and we solemnly raise our glasses.

‘To Dad,’ I say.

‘Dad,’ David repeats.

‘It’s his birthday?’ she asks.

I’m shaking my head as we drink. ‘Uh, uh. His funeral.’

3. Voices

DAD’S FUNERAL WAS a simple affair, just the close family and no priest. By the time we came to say goodbye to him, he had moved sufficiently far away from the Catholic Church for the service to be ignored altogether. No Mass. No last rites. No repentance. None of ‘that’, at Dad’s request and to our considerable relief, although in fact he put it more strongly. Instead, we make it up, not quite as we go along. David says a few words. Mum reads John Donne’s A Valediction Forbidding Mourning. She must have nerves of steel for there is not the hint of a quiver in her voice. My sister Jackie prefers to say nothing.

We’re in the chapel of a cemetery on the outskirts of Durban. It’s a beautiful place, several acres of rolling hills surrounded by frangipani and jacaranda, erythrina and mango trees. While Mum speaks, I start to read the memorial plaques around the walls of the chapel. There are perhaps 200 of them. Robert Louis Stevenson’s Requiem is quoted no less than eight times, and I study the names on these plaques. MacLean, Borthwick, Lee. Scots, all of them, who had come this far and died here, 10,000 miles from ‘the auld country’, and I’m willing to bet every last one of them ‘wearied’, as Dad sometimes claimed to, ‘for the heather’ and the ‘green Highland hills of home’.

Then it’s my turn and, while the others gaze silently at the coffin or the ceiling or their feet, I stumble through the Requiem:

Under the wide and starry sky

Dig the grave and let me lie:

Glad did I live and gladly die,

And I laid me down with a will.

This be the verse you ’grave for me:

It’s the sixth line that gets me. Up to that point, I just about manage to hold it together and to obey Donne’s injunction:

... let us melt, and make no noise,

No tear-floods, nor sigh-tempests move ...

I’m reciting the Requiem from memory and, as line follows line, I realise that Dad must have taught us the words before my memories begin. Not once have I lain beneath the wide and starry sky anywhere in the world but that the lines have come back to me. The hunter is home, he would announce, coming in from the office. I gladly die, he would say at the bridge table before making a sacrifice bid of 5 and thereby robbing our opponents of their rightful game in 4 . And sometimes, apropos nothing in particular, he would recite the poem in its entirety and his voice would take on a slightly stronger brogue while his grey eyes misted over. And it wasn’t just the Requiem, but the entire Stevenson canon. In the restless forests of his life, A Child’s Garden of Verses was a constant and we might at any moment expect to hear a favourite line or stanza or entire poem quoted without context, except that the context was his life, and who he was. He liked the rhythm of Stevenson’s poetry and the journeys. He was much more interested in the journey than in arriving, though it is only now that I see it in the poems he used to recite from A Child’s Garden of Verses.

Dark brown is the river

Golden is the sand.

It flows along forever,

With trees on either hand ...

In the poem, the child narrating it builds boats and sets them afloat on the river, and watches them go out of sight, ‘away past the mill’. And my father’s eyes would cloud a little at the concluding line:

Other little children

Shall bring my boards ashore.

He also loved the rhythms of ‘From a Railway Carriage’ with its

... child who clambers and scrambles,

All by himself and gathering brambles;

Here is a tramp who stands and gazes;

And here is the green for stringing the daisies!

Here is a cart runaway in the road

Lumping along with man and load;

And here is a mill, and there is a river:

Each a glimpse and gone forever!

Dad’s life has been full of such glimpses.

When it came to the funeral, I knew there was only one tribute I could pay. The Requiem continues,

Here he lies where he long’d to be ...

But, at the thought of Dad’s longing, my voice breaks. Tears well up and I lose it completely. I stand, unable to speak or move, wracked by wave after wave of sobbing. I have one hand on the coffin. I’m sure that if I lift it I will fall over. I wonder what one does when one can’t speak, and can’t move and everybody’s watching. Does it stay like this forever?

It doesn’t. The spell breaks and I manage to blunder my way through the last three lines, thinking all the while that it was perfectly possible that none of them was true:

Here he lies where he long’d to be;

Home is the sailor, home from the sea,

And the hunter home from the hill.

And then it is time for the coffin to be taken through the doors at the back of the chapel to the crematorium. To the funeral director’s surprise, we have said we will carry the coffin to the furnace ourselves. I don’t know why; perhaps we wanted to prolong the moment of parting. Perhaps we are just being Balfours, which is to say we are copying Dad’s perennial insistence on doing every last bloody thing ourselves. He was the declarer and he played the hand. The rest could do as they wished.

David, Jackie and I push the trolley through. Mum follows behind, as we go through some heavy curtains, not knowing quite what to expect. We enter a room the size of a squash court. In the middle is a large oven. There are no windows and only a pale neon light illuminates the room. Around the side are a few bare tables and chairs. And in the corner a shovel. The pillars near the door are marked with handprints of grey ash. And seated at the table are the men whose job it is normally to take the coffin and shove it into the oven. They’re leafing through Scope and Hustler and they have put up centrefolds on the walls, silent witnesses no doubt to their daily rota of cremations. They stand up when we come in, but the funeral director motions to them to stand back and they let us do it ourselves. One of them picks up his magazine from where he dropped it on the floor and resumes his reading, if reading is what he was doing.

It is only later that we find this funny. For the moment, we concentrate on the furnace. It is big and dark and has a little glass panel through which one can see whatever goes on inside. A small blue pilot light hisses softly. David and I heave the coffin in. We close the door with a bright metallic clang and look to the funeral director. He indicates a dial on one side of the oven.

‘All the way?’ David asks.

He nods. ‘You want it good and hot.’

While I wonder what it is, exactly, that I want, David turns the dial. Through the glass panel on the door we watch the blue flames begin to lap the sides of Dad’s coffin. And even in that broad daylight on a summer’s day in Durban, I feel the sky growing darker yet and the sea ever higher.

As we turn to leave, I feel the eyes of naked women follow me across the room.

There are matters to be attended to for the memorial event that afternoon. Catering must be arranged, phone calls made. Mum and Jackie will head home. David and I have to fetch a few things from Hillcrest. We’re on the way there when we decide to stop for breakfast.

‘Thank God it’s over,’ I say, but David’s not sure it ever will be.

That evening, Mum is on the phone for the umpteenth time talking to another friend. I listen to her side of the conversation.

‘Yes, on Tuesday ... Yes, I’m sure ... Oh, no, I’ll be fine ... Yes, Jackie’s here, and the boys too ...’

I’ve flown in from London, Jackie from Brussels. David lives and works in a game reserve three hours’ drive away. At the memorial event that afternoon, friends of my parents whom I haven’t seen for twenty or thirty years peer myopically at me.

‘Now which one are you, dear?’ they ask.

‘I’m Sandy.’

‘My, haven’t you grown ...’

But their voices invariably trail off and I never know how the sentence will end. Bald? Fat? Just like your father, who was neither of those things?

And Mum’s holding it together pretty well, quietly answering the same questions over and over. ‘No, there was some pain ... Yes, the drugs helped ... Yes, completely, ’til the very end.’

This last comment refers to Dad’s mind, which, unlike his body, was in pretty good shape when he died.

In the early afternoon, I head back to the crematorium to pick up Dad’s ashes. The funeral director is expecting me. He has a cardboard box on his desk. It’s labelled neatly ‘Mr Balfour’.

‘It doesn’t look like me,’ I say.

‘Sign here,’ says the director.

I sign and then pick up the box. It’s still warm.

‘Busy day?’ I ask.

The director chooses not to reply. I can tell from his face that he has learned under these circumstances that it is better to say nothing.

‘Thank you,’ I say.

My parents live in a house on a hill in a suburb near Durban. On clear days, it is possible to see the Indian Ocean to the east. To the west lie rolling hills covered with well-tended trees and large houses on acre and half-acre plots. The garden at our house slopes away to either side. In the front is a main lawn, a vast expanse of grass, the centrepiece of which is an old flat crown tree. It is very big, the biggest I’ve ever seen. We spread Dad’s ashes there just as dark falls.

Dad loved the tree and it reminds me of him. Its branches spread out above the lawn reaching from one side of the garden to the other. In full leaf it provides perhaps half an acre of shade. It takes in the lawn and the strawberry beds, the banks above what used to be the tennis court and the flowerbeds. It has a huge, thick, smooth grey trunk and flat overarching branches, which stretch out magnificently like some kind of Angel of the South. Below it other plants flourish. This is high summer and the garden looks particularly good. The lawn is green and the azalea is in bloom. The avocado tree is laden with fruit. And the tree has other uses. For as long as I can remember, the monkeys that live in our part of South Africa have used it as a highway from one side of our property to the other. We used to shoot them with the pellet gun in the vain hope that they would eat the neighbours’ fruit instead of ours. The bark of the trunk is pockmarked with pellet scars from where we used to do target practice as kids. Near the base around the back, I find my name half-scratched in the bark. I must have been twelve when I found a sharp knife and started to carve, but I never got beyond the ‘A’. Dad stopped me with a shake of his head. ‘There are better ways to make your mark,’ he said. ‘Let the tree grow.’

As darkness falls, the last guests leave and the telephone stops ringing. Quiet settles on the old house. The four of us gather in the sitting room, unsure what to do or say. Instead, we listen to the sounds of the suburbs. Dogs bark. From across the valley the sounds of a party are carried on the night breeze. A thousand frogs croak. I am struck, and not for the first time, by how comically precarious the suburbs appear to be. For all their appearance of solidity, one has only to witness the extraordinary scale of work that is required to keep ‘the bush’ at bay, the gardeners and lawn-mowers, chemicals, irrigation systems, planting, pruning, hoeing and weeding, to know that should the people disappear it would take only a few years, months even, for the bush to reclaim these immaculate lawns with their swimming pools and herbaceous borders, their tennis courts and arbours. Our property is large and the house too far from the roads for us to hear the traffic, but we can hear the trees creak in the breeze. Every now and then, the old house seems to sigh.

Ours is the kind of household in which a pack of cards is always near to hand. I find myself staring blankly at one such pack on the table in front of me.

‘We could always play bridge?’ I say. But no one takes me up on the offer. They don’t think it’s true any more.

PART II

WHEN MY WORLD WAS YOUNG

4. Walking on the moon

LET ME TAKE you back.

It is the South African winter of 1969. I am seven years old and I do not yet know that I like bridge. In other areas, I have learned to discriminate, which means that, while some things impress me, others do not. I do not, for example, think much of the neighbour’s dog, which barks and dribbles. But I am impressed that every morning the postman cycles up the hill to deliver our letters. He wears a grey uniform and has a drooping moustache. One side is slightly longer than the other. At the back door, my mother offers him a glass of orange squash, which he drinks gratefully.

‘Thank you,’ he says. Beads of sweat form on his brow. He wipes them aside and replaces his cap. I run to the garden gate to watch him cycle away. As he starts to descend the hill, he lets go of the handlebars. I envy the way the wind lifts his shirt.

‘When I’m big,’ I say, ‘I’m going to be a postman.’

My mother smiles indulgently. ‘I don’t think you can,’ she says absently. ‘It’s a job for Indians.’