Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

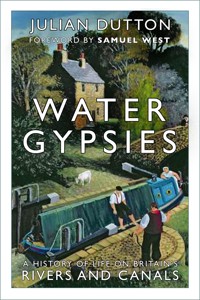

For centuries, living afloat on Britain's waterways has been a rich part of the fabric of our social history, from the fisherfolk of ancient Britain to the bohemian houseboat dwellers of the 1950s and beyond. Whether they have chosen to leave the land behind and take to the water or been driven there by necessity, the history of the houseboat is a unique and fascinating seam of British history. In Water Gypsies, Julian Dutton – who was born and grew up on a houseboat – traces the evolution of boat-dwelling, from an industrial phenomenon in the heyday of the canals to the rise of life afloat as an alternative lifestyle in postwar Britain. Drawing on personal accounts and with a beautiful collection of illustrations, Water Gypsies is both a vivid narrative of a unique way of life and a valuable addition to social history.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 244

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

First published 2021

The History Press

97 St George’s Place, Cheltenham,

Gloucestershire, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© Julian Dutton, 2021

The right of Julian Dutton to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 7509 9758 4

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed in Turkey by Imak

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

BOOKS BY JULIAN DUTTON

Shakespeare’s Journey Home: A Traveller’s Guide Through Elizabethan England

Keeping Quiet: Visual Comedy in the Age of Sound

REVIEWS OF JULIAN DUTTON’S KEEPING QUIET

‘... a lovingly compiled and thorough history of the genre beyond the advent of sound, writer and performer Julian Dutton extols the artistry of dumb-show, pantomime and slapstick… an absorbing, affectionate but critically rigorous account’ – Jay Richardson, Chortle

‘There’s nothing funnier than visual comedy done well. And there’s no more entertaining and informative book about its relevance today’ – Bill Dare, creator Dead Ringers, BBC

‘A custard pie in the face of those who say slapstick is dead, by the go-to writer of British visual comedy’ – Harry Hill

Author’s note: The word ‘Gypsies’ in the title is used generically as a term for nomadic or settled population groups choosing to live and work on rivers and canals, and not to describe any ethnic community.

There should be many contented spirits on board, for such a life is both to travel and to stay at home … and for the bargee, in his floating home, ‘travelling abed,’ it is merely as if he were listening to another man’s story or turning the leaves of a picture book in which he had no concern.

- R.L. Stevenson, An Inland Voyage

A narrowboat family, 1874.

‘Have you also learned that secret from the river; that there is no such thing as time?’

Hermann Hesse, Siddhartha

September Sunshine, by George Dunlop Leslie.

FOREWORD BY SAMUEL WEST

INTRODUCTION

1. INTO THE WILDERNESS

| ANCIENT BEGINNINGS | PRE-HISTORY TO AD400 | CELTIC & ROMAN BRITAIN | WORSHIP OF RIVERS | FISHERFOLK | ROMAN CANALS | RIVER TRADERS, THE EARLIEST HOUSEBOAT DWELLERS | THE THAMES AND ITS TRIBUTARIES | THE FOUNDATION OF LONDINIUM | EVOLUTION OF THE BOAT FROM CORACLE TO CLINKER BUILT | THE FIRST INLAND WATERWAYS VESSELS | LIFE OF A LIVEABOARD IN ANCIENT TIMES |

2. WHEREVER A DUCK GOES: RIVER DWELLING AD 400–1750

| RIVERSIDE LIFE | INNS | CHALLENGE OF WEIRS AND MILLS | THE LIFE OF BOAT DWELLERS | IMPROVEMENTS OF RIVER NAVIGATION | MEDIEVAL PROSPERITY | EVOLUTION OF THE ‘HOUSEBOAT’ FROM WIDE RIVER BARGE TO CANAL NARROWBOAT | BEGINNINGS OF LIFE ON THE CANALS |

3. THE CANAL AGE: 1750–1900

| EXPANSION OF RIVER TRADE | EXTENSIONS OF, AND LINKS BETWEEN, RIVERS | CONDITION OF ROADS | BLOSSOMING OF CANAL MANIA CREATING A FLOATING SUBCULTURE OF POPULATION | APPEARANCE OF THE BIG HAULAGE COMPANIES, PICKFORDS, ROCKS, ETC. | POSSIBLE ROMANY ORIGINS OF CANAL FOLK | LIFE AND CONDITIONS FOR LIVEABOARD FAMILIES OF THE NINETEENTH CENTURY | COMING OF THE RAILWAYS | SOCIAL CAMPAIGNERS | GEORGE SMITH AND THE CANAL ACT | LORE AND CULTURE OF NARROWBOAT FOLK | THE HOUSEBOAT IN LITERATURE | ROB RAT, R.L. STEVENSON | GROWTH OF LEISURE BOATING | GEORGE DUNLOP LESLIE’S OUR RIVER, JEROME K. JEROME’S THREE MEN IN A BOAT, ETC. | STEAM LAUNCHES AND EXPANSION OF COASTAL TRADE |

4. TWILIGHT OF THE TRADERS: 1900–1945

| DECLINING YEARS OF RIVERS AND CANALS AS TRADE ROUTES | DOMINANCE OF THE ROAD | BEGINNINGS OF HOUSEBOAT LIVING AS A LIFESTYLE CHOICE | NOTABLE HOUSEBOAT DWELLERS | A.P. HERBERT’S WATER GIPSIES | HOUSEBOATS AND WAR: THE RIVER EMERGENCY SERVICE | HOW THE SECOND WORLD WAR AFFECTED RIVER AND CANAL LIFE | HOUSEBOATS AND DUNKIRK | D-DAY | THE FUTURE |

5. AN ALTERNATIVE SOCIETY: 1945–2020

| LIVING AFLOAT AS A LIFESTYLE CHOICE IN POST-WAR BRITAIN | TRANSITION OF WORKING MARINAS TO RESIDENTIAL COMMUNITIES | NATIONALISATION OF THE CANALS | THE PLACE OF THE HOUSEBOAT IN CULTURE | NOVELS, FILMS | THE HORSE’S MOUTH, THE BARGEE, THE NAKED TRUTH, HANCOCK’S HALF HOUR | THE HOUSEBOAT IN FICTION | PENELOPE FITZGERALD’S NOVEL OFFSHORE |

6. A NEW LIFE: THE PRESENT

| CURRENT STATUS OF HOUSEBOAT LIVING | RENAISSANCE AS A RESULT OF ECONOMIC PRESSURES ON THE HOUSING MARKET | THREATS TO THE WAY OF LIFE | NEW DESIGNS AND ODD DESIGNS | THE FUTURE |

SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

ILLUSTRATIONS

I’ve never understood why motorways were introduced to Britain without a national debate. It was simply assumed that people wanted to live their lives faster, and get where they were going in the shortest possible time. I’m not so sure.

Imagine a time when rivers, not roads, were the DNA strands that gave Britain its personality. When canals, not railways, were the chosen way of cargo. A track that fords a stream gives a place a reason to exist. Over centuries, the reasons are made solid in wood, iron and brick; take to the stream and the reasons will show you their purpose. On day one you might feel itchy. Persevere, and the life of the waterways will slowly seep into you. Its slowness is its strength. Your heart beats to the speed of the water, the regular slog of the locks, the birds and insects that accompany you. You notice things more.

As our lives get faster and more digital, the desire to slow down and connect with the world outside grows. My parents, Timothy West and Prunella Scales, have very different attitudes to travel. He wants to round a new corner every day; she likes the comfort of familiar surroundings. It wasn’t until halfway through their lives that they realised they could have both if they travelled by water. Seeing Britain by canal – from backstage, as it were – has been one of their greatest pleasures since. As my father points out: at three miles an hour, if anything goes wrong you can always walk where you were going quicker. They’ve now had a narrowboat for more than thirty years. The vagaries of age (and in my mother’s case, dementia) only make them long for time on it more. It fits their shabby-bohemian need sometimes to be on the edges of society. Actors know that feeling well.

But however keen the family is on life on a canal boat, we always stopped short of making it permanent. The challenges of keeping a boat clean, tidy, safe (especially when children and now grand- and even great-grandchildren join you on the voyage) are considerable. And it’s HARD. I will sing the praises of a canal holiday to anyone, but I never pretend it’s not a workout.

Most of the working families and liveaboards that Julian Dutton celebrates in this wonderful book never had a ‘real’ home to return to. Their life was their work, and now that working boats have gone, it’s good to know more about what’s been lost. Then, as now, boat people were a tribe. A mix of Romany, ancient river traders, ex-miners and small farmers would migrate to where the work was, suffer when it wasn’t, and live and die on what they called ‘the Cut’. But beware the ‘semi-rustic idyll’, Dutton warns us: life for a canal family was often dark, cramped, unsanitary and dangerous.

The temptation of a life aboard has always been disproportionate. Even in the 1930s, when A.P. Herbert wrote his classic The Water Gipsies, it felt like a vanishing world. Luckily, campaigners kept many from closure and a life ‘deep, rich and valuable’ was saved.

Julian Dutton grew up on a houseboat and there could be no better or more informative guide to a history of life aboard. Whether you want to know about working boats, prison hulks, Dickensian houseboats, pleasure cruisers, floating restaurants or artists’ retreats, this book is for you. He’s particularly good on the story of bohemian Chelsea collectives that grew up after the Second World War, because of course it’s his story too.

Nowadays water-living is as expensive as land, and mooring fees have homogenised communities just as rising rents do elsewhere. A shame. We need the outsiders of the Cut, living on the edge, throwing darts at the landlubbers. I think perhaps they know something we don’t.

Rivers have often invoked a dream state for poets and writers. For Kenneth Grahame in Wind in the Willows the Thames was a living thing that ‘chattered on to him, a babbling procession of the best stories in the world, sent from the heart of the earth to be told at last to the insatiable sea’. The poet Shelley in 1817 wrote an entire epic work, Laon and Cythna, whilst drifting in a boat beneath the overhanging willows of Bisham near Great Marlow. Jerome K. Jerome’s bestselling Three Men in a Boat (also written in Marlow) is perhaps the ultimate ‘getting away from it all’ novel, and it is to the river that he and his companions, weighed down with late nineteenth-century civilisation, flee in order to satiate their longing for escape.

Is it this dream state, this liberation from the trammels of ordinary consciousness, that people seek when they choose to leave the land behind and live on the water? Or perhaps it is a quest to answer a deep ancestral call, to reawaken buried instincts: somewhere far inside the soul of an accountant a voice pleads ‘you must abandon these dry figures, and go off to sail, drift and fish’ – and the price of not heeding that voice is to suffer at best a restless discontent, at worst a spiritual death.

Whatever has impelled people to leave behind ‘ordinary life’ and take to the water, the history of the houseboat is an evolution from necessity to choice, and tracing its line all the way from the fisherfolk of ancient times to the bohemian artists and writers of post-war England and beyond, to the current wave of some 30,000 liveaboards, is to delineate a unique and fascinating seam of British history. In almost every history book, living and working afloat achieves at most only a passing mention, despite being an important part of British life for centuries. There are numerous works on the history of canals and rivers, yet most focus exclusively on the economic and industrial dimension; none tell the complete social history of the life and lore of those hundreds of thousands of Britons who over the past two millennia and beyond have spent their lives adrift.

This book attempts to fill that gap. Its aim is to chronicle a way of life dating back to prehistory. From the trading vessel where a sailor or merchant might live for weeks aboard his craft, to the generations of canal bargees plying their narrowboats along the industrial arteries of the nation for centuries until the railway – and later road haulage – signalled their decline, to the post-war baby boomers of the 1950s seeking a different lifestyle to that of orthodox mainstream society, and contemporary families searching for a more economic form of homeowning when house prices are challenging a whole new generation, the story of houseboat dwelling on the waterways of Britain is a rich and varied one, containing as many twists and turns as the riverways they have chosen to make their home.

The necessity began, of course, in the pre-Iron Age settlements before the invention of agriculture, when hunting and gathering meant a coast-hugging life of fishing or, for the inland tribes, harvesting the rivers and lakes. And what easier way to gather aquatic sustenance than by living on the water itself? Ghostly remnants of these water-borne villages still dot the British Isles – the blunted remains of jetties supporting long-vanished huts, the occasional glimpse of oak foundations when tides recede. At Llangorse Lake in Brecon one can experience a fine reconstruction of one of these ‘floating villages’, stretching out across the glistening waters richly inhabited by plump fish of all kinds, to be gathered daily by families living right above their quarry: stout piers supporting habitations whose foundations were buried deep in the mud of the lake or riverbed. Not strictly ‘houseboats’ on the lakes so falling outside the scope of this book, but the coastal folk trawling the oceans of this island would often travel for days, seeking the extensive shoals further offshore, living aboard. It is these anglers, along with inland traders stretching from the Neolithic age onwards, who are the ancestors of our modern houseboat dweller.

While the river traders who traversed the Thames, Severn and Trent in ancient and medieval times were the first historic ‘houseboat’ dwellers, the first modern liveaboards were the inhabitants of the man-made waterways when canal mania carved the country with hundreds of man-made ‘cuts’ criss-crossing the nation. These arteries carried tonnages to the growing industrial centres of the nation, and in so doing created two things: Britain as the first powerhouse of the world and the boat as a place of permanent dwelling. In the period between 1760 and 1840 when railways displaced canals as the prime mode of industrial transport, people flowed from the land to the water, and thousands of families began a life afloat, lasting many generations right up to the 1960s (as late as 1964 life on the canal was still considered a sufficiently widely known way of life for Associated British Pictures to release The Bargee, a comedy about a canal worker starring Harry H. Corbett – admittedly a film that served as a eulogy to the way of life, but nevertheless a marvellous portrait of the dying days of canal living).

The first major modern boat dwellers, then, were the canal folk, whose homes traversed the country between the growing coal centres of Britain, fuelling the nation with steam power and eventually lighting all cities and towns with coal gas. As early as 1768 the promotion of the boat over the horse was noted in the House of Commons, its Journal proclaiming that, ‘one horse will draw as much upon a navigable canal as one hundred will draw upon a turnpike road.’ Such an elevation of the boat as supreme carrier of the nation bestowed an importance on the boat dweller that lasted nearly a century, for even when rail had overtaken the canals, water-borne trade continued as a driving force of British trade, albeit a weakened one as rail and road became supreme.

If the story of the canal boat as place of residence for the bargee and their family is a fascinating one, the development of the houseboat as an act of choice in pursuit of an ‘alternative lifestyle’ in the twentieth century is equally rich, and of huge cultural import. In the period up to the 1940s there was still extensive river-borne trade along the Thames, but alongside these working families plying their wares along the waterways the new century saw the rise of the non-commercial houseboat, many famous devotees of aquatic living giving credence and not a little notoriety to this alternative way of life. Noted barrister and author A.P. Herbert was one such legendary figure, famously residing with his family on a barge moored at Hammersmith. Whilst being known as a humourist, Herbert’s books on houseboat life were equally well received, his novel The Water Gipsies (1930) figuring high in the canon of houseboat fiction. It is Herbert’s life too that advertised the important role of the houseboat in war, for during the 1939–45 conflict houseboats, including his own, were enlisted in the hugely important River Emergency Service, undergoing patrols and other vital war work up and down the Thames and other British rivers.

In the post-war years the houseboat became bohemian and slightly raffish, a place of beat poetry, bottle parties and film actors: Dorothy Tutin famously inhabited a London barge, and films such as The Horse’s Mouth with Alec Guinness and The Naked Truth with Peter Sellers and Terry-Thomas made the floating villages of London famous on the big screen. I myself caught the ebbing tide of this wave of houseboat living, being born on a boat moored in Cheyne Walk, Chelsea, and growing up in the 1960s in what is now known as Chelsea Reach – and was, indeed, inspired to write this book when I made a return visit, years later, to this floating village.

I wondered how the years had wrought their changes on this little pocket of 1950s bohemia, this ensemble of actors, artists and boozers, this much-sought-after locale of films such as The Spy Who Came in from the Cold and many more. Who now was living in the boat where I used to sit on deck as a boy and watch the clouds of smoke from nearby Lots Road Power Station, or wave to the barges chugging past the Chelsea Flour Mills? Who now was being rocked to sleep by the ebb and flow of the Thames, the smell of boat tar, cracked leather and paraffin in the nostrils, feeling all the time that we were on a camping trip yet only yards from the King’s Road? Had houseboat living changed in the intervening half-century?

My return journey to the houseboat community where I grew up led me to make further investigations into the history of living afloat, and out of those investigations this book was born.

Chelsea Reach differs from many other houseboat communities in that none of the craft are narrowboats – they are mostly wide-beamed converted landing craft bought up by an enterprising marine owner in 1945. None has the cramped feel of the canal barge and most have two floors. Despite the size of the dwellings, however, the air of a shanty town still lingers. Growing up here in the 1960s I have dim but possibly apocryphal memories of wives beating washing on the stones revealed by the morning tide, much like folk on the banks of the Ganges. We lived on top of each other, borrowed each other’s food, money and clothes, heard each other’s parties, rows and intimacies. But who lived there now?

It took me ten minutes to navigate the busy traffic of Cheyne Walk, but as with all houseboat communities, as soon as you approach you enter a different, quieter world: hidden behind the huge Thames wall, reached only by gangplanks, here was Chelsea Reach – a world apart, a village in magical isolation, almost like Brigadoon.

The river is wide here between Battersea Bridge and Sands End, mud-brown and peculiarly desolate, contrasting violently with the warm, colourful nest of houseboats tethered to its bank. One is hit by the sudden, warm stench of a mossy grey river smell, a scent familiar to me from childhood. Also unchanged are the serpents of twisted steel ropes snaking through the sloppy mud, lashing their hulking charges to the great rusting iron rings sunk into the slimy Thames wall. The colours of the boats too had not altered – fairground pinks, flame, violet with gold curlicues, rich purples, curved splashes of flamboyant rose – an echo of the exotic boat-painting tradition from centuries gone by. And the names – The Patriarch, The Odyssey, The Dinty Moore, The Kandy-Koloured Tangerine …

And the Moby Dick, my birthplace? Living there now is a graphic artist couple; their neighbour is a barrister, and next door but one is ‘a lovely couple: he’s a production executive and she’s a production designer’, and they have ‘full plumbing and electricity’. The only remnant of the old days is a tank-duct for the chemical toilets. The Flour Mills further down the bank are gone, replaced of course with luxury flats. And the rent? Several thousand a month. (My parents bought our boat in 1958 for £500.) A vessel here will set you back a minimum of half a million.

And yet, for all these changes, one vital thing has not altered, and that is the social diversity of the occupants; indeed, the one thing they have in common is the impulse and desire to live afloat. It is an impulse borne from the need to live a different kind of life, away from mainstream society. Boat living attracts people from all sorts of backgrounds, rich, poor, the ambitious and the wastrel, the artist and the inventor. It is the desire to occupy a place outside the stream of normal belonging, where one wakes not to the sound of car horns or refuse lorries but to the whisper of the river, the song of the wind through the trees on the banks, the chatter of waterfowl. It is a perennial impulse that drives people to keep one foot firmly in nature, in a little bit of wilderness, as an antidote to the sometimes stifling effects of a suffocating modernity. E.G.R. Taylor, reviewing W.G. Hoskins’ seminal work The Making of the English Landscape, wrote that he:

views the industrial revolution with mounting horror, and the industrialists themselves are bitterly chastised as completely and grotesquely insensitive. Hoskins has happily moved to a quiet spot in Oxfordshire where he … looks out of his study window on to the past, (and) draws for us a last tender and evocative picture of the gentle unravished English landscape, and forgetting all the horrors, reaches back through the centuries one by one and rediscovers Eden.

It is that call, that inward impulse, that yearning for Eden, that thousands of British people have listened to across the centuries, and obeyed. It is that impulse that is the beating heart of this chronicle, the story of the British houseboat and life on Britain’s rivers and canals.

| ANCIENT BEGINNINGS | PRE-HISTORY TO AD400 | CELTIC & ROMAN BRITAIN | WORSHIP OF RIVERS | FISHERFOLK | ROMAN CANALS | RIVER TRADERS, THE EARLIEST HOUSEBOAT DWELLERS | THE THAMES AND ITS TRIBUTARIES | THE FOUNDATION OF LONDINIUM | EVOLUTION OF THE BOAT FROM CORACLE TO CLINKER BUILT | THE FIRST INLAND WATERWAYS VESSELS | LIFE OF A LIVEABOARD IN ANCIENT TIMES |

In the late 1880s the writer and sailor Joseph Conrad was gazing out from the deck of the yawl Nellie moored near Gravesend. With a stub of pencil he jotted down some notes for a novel he was planning, Heart of Darkness. He wrote:

The sea-reach of the Thames stretched before us like the beginning of an interminable waterway. In the offing the sea and the sky were welded together without a joint, and in the luminous space the tanned sails of the barges drifting up with the tide seemed to stand still in red clusters of canvas sharply peaked, with gleams of varnished sprits.

Conrad knew he was looking centuries back in time. For the sails of England’s riverboats were truly tanned, and had been since time immemorial, caked with the distinctive ochre pigment of horse fat, cod oil and seawater, turning the inland waterways of Britain into a flowing forest of reddish brown.

Conrad goes on to imagine what a Roman might have seen on his first encounter with ancient Britain: swamp, mist, lowlands carpeted with forest – essentially a wilderness. London did not exist, being an estuary of swampland and thick woodland stretching to the north and west on deep beds of clay. No bridge crossed the Thames. The Romans laid down the foundations of Londinium only by dint of the two gravel spurs making that part of the river fordable. If those two spurs had been situated 30 miles upstream, the capital would have been Maidenhead. The very existence of any inland settlements, let alone towns or villages, lay far in the distant future, and would owe their birth and growth solely to the waterways that ran through their locality. Apart from the occasional man-made mound, barrow, cairn and isolated farming communities of stone huts and thatch, Britain’s landscape was wild. Even as late as the Elizabethan era travellers would describe the country between towns as ‘heath and wilderness’. From the very beginnings it was the inland waterways of this country that dictated the entire geography of human settlement and activity in the ensuing centuries.

It is in this wilderness that the houseboat is born.

The Dover Boat, sailed by Bronze Age traders. At 3,500 years old, it is Britain’s earliest vessel. (Dover Museum)

The Romans had long known that Britain was a boating nation. The first-century writer Lucan writes in his Pharsalia (also known as The Civil War):

When Sicoris kept his banks, the shallop light

Of hoary willow bark they build, which bent

On hides of oxen, bore the weight of man

And swam the torrent. Thus on sluggish Po

Venetians float; and on th’ encircling sea

Are borne Britannia’s nations.

It’s an extraordinary eulogy to the ancient coracle, or curragh, bearing testament to the robustness of Britain’s international reputation for seamanship, for while Venetians drift idly down the ‘sluggish’ Po, Britons brave the oceans. Other historians bear witness to British sailors traversing the North Atlantic in the humble leather-bound vessels.

Brave though the Ancient Britons may have been, when we travel back in time to those ancient days beyond the Roman conquest it is important not to downplay the dangers of travel by water, and to adopt vicariously the very real fears and anxieties many of our ancestors would have harboured towards the rivers of this island. Compared to prehistoric times our rivers are now (relatively) tamed, domesticated, parcelled, with locks and weirs controlling the flow, man-made embankments cauterising floods (in many cases), and fragrant towpaths occupying the margins of the waterways where once woods and forests hid wolves, bears and other predators. For our ancestors, to set out on the river was often to take one’s life in one’s hands, submit to the fitful whimsy of wild current, waterfall, or attack both animal and human. There were many reasons that inspired or compelled our ancestors to overcome these perils and travel and live on the waterways – migration from hostile tribes, fishing for subsistence and trade.

It is only the latter – trade – that began the slow creation of what was to become a significant subculture of ‘live-afloats’, and it is that subculture that we are setting out to trace from prehistoric times to the present day.

The first true ‘houseboat dwellers’, then, were traders, and the earliest characters in the long story of living afloat are those who took to the water in a primitive vessel – large dugouts, and then wider vessels made from several dugouts attached by horizontal planks – probably loaded with Neolithic axe heads from one of the many ‘factories’ to another part of the country. The journey of these early liveaboards, though inland, was nevertheless not without peril.

It is only through this lens of danger that we can gain a true picture of what our forefathers felt towards the waterways that have snaked through Britain since the retreat of the ice 10,000 years ago. To our ancestors, nature was untamed, full of gods and unseen forces to be feared and placated. It is a short mental step from fear to placation and devotion. To find out precisely how ancient Britons felt one can do worse than observe contemporary Hindus of India, who to this day descend the stone steps (ghats) of their towns along the banks of the Ganges every morning to bathe and give worship.

Such votive reverence would have been the same for our ancestors. Even in the post-pagan Middle Ages pilgrim effigies – small crudely carved statuettes – were tossed into the Thames; in pre-Christian times to supplicate gods, in Christian times Saints, the reverence is the same.

The worship of water is as old as history. And this imputing of divine or supernatural qualities to waterways lingers to this day. Even as late as 1882 during a search for a drowned woman in the River Derwent at Milford, people took with them a drum which they beat over the water. Tradition held that at the point where the drum gave forth no sound, there lay the body. To this day, supernatural powers are projected onto natural phenomena, such as the Aegir of the River Trent, a high spring tide meeting the downstream flow that causes a high bore wave that for centuries has swept unsuspecting folk to their deaths. The ghosts, gods and monsters of the rivers are sometimes nurturing, sometimes avenging, to be appeased or thanked accordingly.

As with the waterways, so too the craft. Even now vessels are launched onto the rivers and seas with a mysterious ceremony, including the breaking of the ‘neck’ of a bottle, thought to be an echo of the human sacrifice sometimes made before a water-borne journey. The entire lore of boats is steeped in folklore, superstition and ritual, and will be etched throughout this book.