6,49 €

Niedrigster Preis in 30 Tagen: 6,99 €

Niedrigster Preis in 30 Tagen: 6,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Buzz Editora

- Kategorie: Ratgeber

- Sprache: Englisch

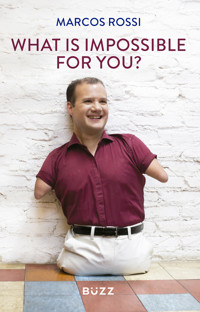

An obstetrician faints after he takes the baby out of his mother's belly. A young man surfs beyond the breakers, with his crutches supporting him on the board. More than a hundred musicians from a samba school watch in silence as a guy in a wheelchair, who wants to be part of the drum section, takes the test. A street musician touches people when he sings "I Believe I Can Fly" on weekends at Paulista Avenue. Benny, the mascot of the Chicago Bulls basketball team, puts his mask on a disabled spectator, to the delight of the entire arena. A grown man, lawyer, and father of two has butterfl ies in his stomach as he faces the crowd in his fi rst speech as a motivational speaker. What brings these episodes together? Born without arms or legs due to an extremely rare disability, Hanhart Syndrome, these are scenes from the incredible life journey of Marcos Rossi, described vividly and with good humor in this book, What is Impossible for You?. With the candor that only the courageous possess, Marcos shares with us the circumstances of each one of the conquests he had reached in his daily search to overcome challenges and limits (both our own as well as the ones that we impose on ourselves) without any self-pity or playing the victim. He teaches us not to carry frustrations or sadness out to the following day. His story shows us that it is required never to give up our dreams. In the end, there's one thing that will be really impossible for you: remain the same after reading this book.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 282

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Ähnliche

Table of contents

Cover

fontmatter

Acknowledgments

What is impossible for you?

Footnotes

Copyright

Landmarks

Capa

Folha de rosto

Créditos

Acknowledgments

I thank God for putting such good people in my journey, without whom I perhaps wouldn’t have made it this far:

My wife Lucimeire, who always gave me support, a lot of love, and on several occasions taught me to “step on the brakes” and to look at things differently. My perfect and eternal girlfriend, adventure companion, and Carnaval companion.

To my mother, for having guided me and supporting me for decades, even in the difficult times.

To my father, my best friend, who believed in me, encouraged me, and did all that he could so that the dream would come true 10 years ago, at the most important moment, when I decided to fulfill my life’s mission and show people how to reach their dreams through my talks.

To my children, for making me want to be a better person every day.

To my sister Nina, who is always here for me even though she has been living in U.S. for the last 10 years, to her friend Robert Jackson who has been a fan since the beginning of my career, who presented me with the first English translation of this book.

To my friends and life siblings: Fábio, Paulo, Alexandre, José, Weslley, Fernando Herrmann, Alessandro and Priscila, Didi, Maurício Patrocínio, Bruno Guazzelli, Sergio Pato, Rodrigo Pescador, and William Spinetti, for the several ocassions that they gave me that push so that my dreams could come true.

To my circle of mentors: Professors Mário and Orlando from the Souza Lima Conservatory; Aldo Novak, who, through his teachings, enabled me to open my mind and introduced me to Rosana Braga, who, for her part, welcomed me in her interview program and introduced me to the world as a speaker even before she was Rodrigo Cardoso’s wife, who taught me how to be a “person who goes beyond limits” and to defeat my inner barriers, as well as introducing me to the masters of the book pub- lishing, Anderson Cavalcante and Cintia Dalpino, who believed in and made the dream of making this book possible.

I love all of you! I felt like I was being thrown out. My heartbeat skyrocketed. I broke into a cold sweat.

“What do you mean, leave?”

That moment had been coming for a long time. I was 32 years old, which was itself a miracle, for since when I was a child doctors had been saying I wouldn’t make it past 30. I was 32 years old at that time and living with my mother. As a matter of fact, I was living in an apart- ment next door to her, but under her supervision. As if the umbilical cord was still attached, there were no secrets between us. It was a dependency that didn’t make me uncomfortable. On the contrary.

Yet, my mother gave me an ultimatum. And it was difficult to have to deal with another move. Another challenge. But this was a big one that came out at an unexpected moment. How was I, without arms or legs, going to leave this place for somewhere else? How would I make this shift on my own? How would I walk on my own legs, if I didn’t have any?

Without knowing it, she was providing the biggest challenge I would have to overcome in my life.

I felt the same way the very day I first surfed. Time had stopped for a few moments. A bead of sweat trick- led down my forehead and that sensation became even stronger. I closed my eyes. Took a deep breath. I could almost feel the ocean breeze. The waves breaking. I was being carried, fearful and anxious, beyond the breakers by my friends. From the beach into the ocean. That was where that feeling made me more powerful. The adrenaline made me tremble. I was on the surfboard, supported by crutches. People stared all over the place.

How would a guy without arms or legs surf? How was he going to keep his balance?

I didn’t know either but somehow I would. And if those questions didn’t have any answers up until then, the guys who were betting it would work out carried me out beyond the surf, that area where panic and pleasure set in. Panic and pleasure. How could those mix? It was a time where I knew anything could happen but I must have faith. Faith that things would turn out as planned. Faith that, in case I turned over on the board, I would be able to hold my breath for at least a minute until someone turned me back up. And faith was more or less the basis of my life. Faith in destiny, faith in God. Faith in life and in everyone around me.

I had believed, ever since I was little, that believing was the first step before anything could happen. I didn’t have the slightest doubt that faith could move mountains. But did we know how to move the right mountains? Did we all have the notion of our infinite, unlimited potential?

I trusted.

I trusted like I had never trusted in my life before. Every minute was precious. It was important. It was necessary. And my life was all about rejecting waste. Especially the way the minutes were wasted. That minute until being rescued. There, in that ocean, I closed my eyes and imagined it happening. That was my driving force. That was how I made everything happen. Believing and moving in the right direction. It would be the first time I would surf. That moment was historic. Epic. Suddenly, I heard that voice:

“MARCOS, NOW.”

And that sentence sent me off to another episode in my life. A day that I had replayed in my head so many times that I can describe it in rich detail.

I was 13, almost 14 years old, when I was expelled from school for the first time. A “boys will be boys” moment. The first time causing mischief is unforgettable. The entire classroom was throwing chalk at the teacher’s head while she was writing on the blackboard. She turned around angrily to punish whoever was responsible for that annoyance. She yelled at us, demanding to know who had done it.

Right away I came forward: “It was me, teacher.” But the joke, while led my classmates to roaring laughs, cost me dearly. She knew I was the only person who couldn’t have done that since I didn’t have any hands. When she said she was going to call security, I went to the front of the classroom, towards the door, blocking her exit, slowing down until the wheelchair stopped. “The battery ran out,” I said. That was like poking a jaguar with a short stick, what granted me my first school suspension, which I will never forget.

In my second piece of mischief, newly motorized with my wheelchair, I raced down the hallway, despite t school guards warnings, all the way to the drinking fountain which was at the end of the hall. Instead of slowing down as I got near it, I sped it up. Even though I didn’t know why, that made me happy. However, I was going too fast and I crashed into the drinking fountain, which broke, making water gush out everywhere. The janitor didn’t hesitate to report me to the director right away, who, after seeing my mischief record, expelled me from that school with no mercy. I describe this episode to show that in no occasion did I play the victim. Instead, I am very normal and love to joke around with respect to my situation.

In the lectures I give, I usually say that married couples have nowadays an average of one and a half children. When I read the results of that research I found it curious. So I thought: “I am that half.” But I’ve never felt like being half of anything. Quite the opposite. From the beginning, I was a guy who was completely whole in everything he did. Sometimes I was so intense that I seemed more powerful than a person who walks around with a full body and an empty mind.

All joking aside, at 13 years old I already had a voracious curiosity about sex. At 15, when I found out I needed to undergo a surgery in which the odds of surviving were 10%, the only thing I was worried about was not dying a virgin. Yes, I would have to go under a surgery. Yes, I could die during it, and the chances were so great it made me think of something known as your last wish. Even though I didn’t actually believe I would turn out to a ghost during something as predictable as a surgery.

After all, what else would a 15-year-old boy think about? Sex was a fantasy that practically drove me crazy, since I hadn’t had it yet. And I had no way of enjoying that pleasure other boys my age had already experienced for they had parts of their body helping in the process.

I was definitely worried about scoliosis, that damn illness that bent my spine and made it curve so much there was a risk of my ribs piercing my vital organs. The doctor said I might die if he didn’t insert a steel rod in my spine so it wouldn’t bend more. Leaving a doctor’s office hearing that really sucked. Putting in a rod would also suck. But that I would find out later.

To top it off I couldn’t lose blood since bleeding could be fatal due to my anatomy. But I knew I was going to stay alive. At that time, these matters of life and death weren’t mysterious to me anymore. But I had always been certain that I would live each moment I was inside of my body intensely. And even if I weren’t able to use 100% of everything, at least I would use all resources around me so that my time here on Earth would be spectacular and limitless.

That is how I’ve been thinking since I was a little kid. That is how I decide to live my life. That’s how I had gotten accustomed to it. Forgetting that there were physical limitations. That is to say, in fact, they don’t exist. But at 15 years old, I didn’t know of any theory that proved it. And at that age I wasn’t so daring either. I just wanted to have sex before I died. And that was so clear to me there was no way to avoid it.

I had been born with a rare disability known by the name of Hanhart Syndrome. I basically didn’t have - and still don’t have as they have not sprouted into existence - arms and legs. When the scheduling of the fateful surgery to put the aforementioned rod in my spine finally was set, what was I thinking about? Sex. Most friends of my age were also thinking about it. Perhaps not with as much curiosity as me. But they weren’t supposed to die soon; they also had arms and hands in case they wanted to experience sensations without a fem inine presence. I did not.

Out of the most difficult limitations I’ve had to face, this one makes it to the top 5 list. To want to do something and really not being able to do so, because you need the presence of a second person, made me want to hit my head against the wall. It was different than eating, peeing, or taking a bath. Those were basic needs for which I depended on some people.

I had already seen some pornographic videotapes. I knew what to do. Unlike people in wheelchairs whose lower limbs are paralyzed, I could feel my sexual organ throbbing. And not being able to touch it left me way too tense. Young people who are tense do stupid things, I know. But sexual tension in a pubescent boy is almost explosive, to say the least.

I told my mother I didn’t want to die virgin. As simple as that. And she was speechless. She was deep down afraid I would die in the operating room. The truth is that she was afraid the 90% mortality chance was real and she really could lose her son.

My mother had her natural worries over me at that time. And perhaps that specific one had never crossed her mind. While she was worrying about the outcome of that surgery I showed up with that curious inquiry, what turned everything even morecomplicated for her. I thought I wouldn’t be heard or even get a response, but it arrived a few days later.

After that conversation, which sounded more like a monologue, she didn’t say anything else. But, less than a week later, I was dressed in nice clothes, with a scent of eau de cologne, so that I could be taken to the doctor. Doctor? I knew there was something really strange about that visit to the doctor. A good family friend, who has being in a wheelchair as well, would be the one accompanying me. In fact, he was the disabled male role model I had as a child. A driver was ready to take me to the visit. This family friend had recommended that doctor, and the excuse given for this outing was that I would be getting a second opinion.

During the trip that day, I was wondering what they were up to, but everyone was quiet and no one gave me any clues. Suddenly I felt something was up: that friend of mine said we would need to take a detour to pick up something at a friend’s house.

Without knowing what was going to happen, I was taken by the driver to an apartment door. The driver sat me in my wheelchair and my friend gave the excuse that the driver would take me first because two wheelchairs wouldn’t fit in the elevator. Of course, I didn’t suspect anything at that moment. Everything appeared to be in order. We waited for a few seconds in the corridor until the door opened. At that moment, I knew what life had in store for me.

Yes, I deserved to have that dream come true. She was blonde and voluptuous under a tight black dress that showed off her waist and allowed her thighs to get my attention. May medicine forgive me, but that was much better than any drug. Her perfume was sweet and she played with her hair and her words in a way that any 15-year-old boy would be hypnotized. Before leaving, the driver was emphatic when he told her, “Take good care of him.” I said goodbye to the driver. I had already gotten the message. And if our friend thought that my last wish could be fulfilled by a working girl, who was I to doubt it? Definitely, I was not going to die virgin; moreover, my first time would be unbelievable.

The first thing she did, after saying goodbye to the driver and closing the door tightly, was to take me out of the wheelchair. But she didn’t seem to have much practice at that. I was only able to tell she was also an actress when she acted a little clumsy when pretending she didn’t know how to throw me in bed and fall on top of me.

But her performancedeserved an Oscar.

I have not forgotten a fraction of a second of that day. I spent five intense hours learning absolutely everything on female anatomy, about the pleasures my body could provide, and the ones I could feel as well. On that day, I understood that my body was a good machine, that I could also give pleasure and, above all, that I could spend the rest of my life doing that. That is, if I survived that surgery. I left the apartment walking on clouds. Or rather, float ing on them, since the wheelchair was carrying me.

Who would have thought a visit to the doctor could be so full of pleasure?

The following days, and the days preceding the surgery, were calmer than I could have imagined. Although I was worried, something told me that I wasn’t going to die there.

There were odds up to 90% that everything would go wrong.

In my life, chances that things would go wrong were very large but I always challenged all of them. People were constantly telling me to be careful. Daring was a strong characteristic of my personality which I would not give up. I was starving to savor life. To devour it. I was certain that I had not been born this way by chance. I needed to make it happen. I needed to prove to everyone that limits were only mental restraints, that circumstances would always point at us obvious negatives, but that our mind… ah, it could go beyond that. Beyond beliefs, fears and whys. And, assuming this, even finding myself in an allor-nothing situation, I admitted that I wanted to live. My strength was greater than my fears. And I had to admit I didn’t believe I was going to die so young.

I had played with my mother’s psychological side because I believed in fact that my life would be long. That I would die at the right time and date. And that I still would have many things to live, learn and experience.

I went into the operating room and closed my eyes. My life’s movie would be played within seconds. I was 15 years old.

Who dies at 15 years old?

“MARCOS, NOW” - said a voice that seemed to come from far away.

“MARCOS, NOW”.

I started to play. There were 170 musicians in an agonizing silence while I had been observed and judged.

My intention was to join the drums section of a samba school. The only one that accepted the challenge was X-9 Paulistana. I had never imagined being in that place nor having that entire group evaluating me. And much less did I have the aspiration of doing that. But a good friend had teased me while we were at a Bloco de Carnaval1. When he asked, “Why don’t you play in a professional samba school, the kind that parades through a Sambódromo2?” I asked myself, “Why not?”. That was a question I used to ask myself every time a challenge came up. And if there is a thing I’m addicted to, it is a challenge.

I played solo for 30 seconds. It was 30 seconds of panic and pleasure. I didn’t know I could feel so many things in such a short time. That the music would flow through my bloodstream and that I would need to review my concepts of emotion after that experience. After so much work learning how to handle the instruments, I was put to test.

Adrenaline made my body shake. Every inch of my body followed that rhythm. If I could describe the feeling, I would say my blood smiled as it ran through my veins and jumped for joy with each heartbeat. My heart was pounding, beating to the rhythm of the instrument I played. There were so many vibrations there I thought about naming them. They were running through the air, reverberating through time and space. They gave meaning to my entire life. I didn’t need to pretend I wasn’t excited. There was so much life in that assembly hall it made me realize how much people were betting on me to succeed.

There are few things that made my heart beat like that. If inspiration somehow fail, I would look for that rhythm, that perfect beat that comes before surmounting something big. Was it an addiction? Perhaps. But this feeling is what makes these remarkable experiences in my life so meaningful, the ones I would be proud to tell my children someday.

While looking at each member of the drums section, surprised and slack-jawed, I remembered the astonished gazes from people who eventually see me holding my son on my lap for the first time, as well as each stare from those who see me typing, playing an instrument, or even singing at Paulista Avenue for the first time. You know, it’s always that expression: “How does he do that?”

It was the expression that tormented everyone at the beach on the first day I rode that wave I had dreamed about for so long. I accepted the call: “MARCOS, NOW”, and acted on it despite the fear. Me and my crutches on the board. Like a tripod. Two crutches in front and my hips on the rear. I remember people’s faces as they were watching that episode and saw the movement of my shoulder, playing with the board, putting my weight on the back to balance my body. Next thing I knew, there I was, surfing. The wind kissing my face, the wave breaking. It felt like freedom. Of overcoming one more challenge. Of defeating a fear, of allowing myself to live, in spite of the dangers. Even with its limits. Those seconds brought me life andenergy I needed to move forward. The guys brought me onto shore. We celebrated it. And that feeling of victory made me understand I had to go through all of that. That celebration granted meaning to all challenges.

“Marcos, are you listening to me?” I was. My body was there, present for that discussion about leaving home, in front of my mother, but my mind was wandering. I was traveling through time and space. As if something was telling me if I could get through that crashing wave, I would be able to surf any waves. But I needed to go through that first.

I attempted to smile, like a confident person. I remember the day I was running the pickups, as a newcomer DJ at a nightclub, as well as the first lecture I gave to hundreds of people.

It was time to face one more challenge. “MARCOS, NOW.”

This time the voice came from my subconscious. And it has always showed up to tell me what to do.

I browsed through my childhood photos in an attempt to escape from that situation. I couldn’t believe what was happening.

It was a brand new feeling.

“Marcos, are you listening to me?” she shouted, anxious for a response.

She didn’t look like herself. She really meant what she was saying and I didn’t know what to think.

Being a father was not in my plans at that time. But she was pregnant. We weren’t married, we had sex a couple of times, and we were taking the first steps towards a real relationship, but… a child?

I imagined myself having a boy.

Everything would suddenly change in my life. I would have to deal with new things, with having a different per- spective on life. With the possibility of taking care of someone. I would be a father. And being a father wouldn’t be easy. Being a father required having to think more about someone else than about myself. Being a father required growing up. Being responsible. Being a provider. Being a role model.

Could I be all that? Would I be able to face that challenge as well?

“Marcos, are you listening to me?”

I was, but my body seemed to be far from there. I felt transported to a different time, a different place. I listened and captured the memories that brought me the same sensation. The same feeling, yet placed at another time in my life. With so many things that had already happened, I went thoroughly over my brain synapses looking for solutions for the things that sometimes made me apprehensive. I was lost. As if I was looking for references. Things that would tell me that everything would be okay. Every man who receives that sort of news feels a subconscious fear in their innermost self. Along with happiness comes that sense of responsibility. To me it was like a game absolutelyforeign to me. I had my own special needs and physical limitations. Would I be able to handle helping to raise another human being? It was too much information in my head. And it was the second time I had received that kind of news.

The first time, with a former girlfriend, things didn’t go as planned. She lost the baby at the beginning of the pregnancy; the dream and fear of being a father had been taken away from me since then. When I was getting used to the news, I received the bad part of it, which took away all expectations. But fate wanted to give me another chance to pass on my values. And, despite the fact that the reproductive instinct is one of the strongest of them all, I was still scared about how to face fatherhood.

I looked at some pictures. They took me away to a distant past, where I was still a child. Where I didn’t get so worried to the point of becoming uncomfortable. I was a little more than five years old in the snapshot, dressed as a clown. I was simply a child, yearning to participate, to have access to all the fun other people could have. I just wanted to be someone who enjoys the same sensations. And that was perfectly possible.

That seemed so distant, and at the same time, so current. Memories do that with us - they turn upside down everything people believe in. They bring new elements, make us push hidden information into Pandora’s box so that we can have ammunition to counter certain realities that are still unknown to us.

There I was - facing news that I would be having a child. In normal conditions, a child is already a big transformation. For me it was one more big challenge. That coming wave we don’t know if we’re going to drown or are going to surf the best wave of our lives. It’s a game- changer for many people.

I had friends with children. I knew it wasn’t that simple. At the same time, I was completely sure that the way I faced this would make all the difference.

What resources could I use to handle this new reality? Images were getting mixed up in my mind, flashes of my childhood games. Curious moments that proved to me that I was capable. Moments that were more meaningful than any word. They brought smell, color, and hope. They showed that the difficulties were in my mind. That the way I had always dealt with changes was decisive in molding my way of living, of celebrating life.

Celebrate life. That’s what it was. A child would bring me the chance to celebrate life like I have never done before. My heart was slowing down, but it was still beating irregularly. As if somebody had injected adrenaline into my veins and I had to put up with a bad change before a total breakdown. This was different than anything I had gone through until then. Stages of my life were coming and going and I was looking for each one of them in my memories. My sense of smell didn’t betray me. It followed every mental image and I shortly rediscovered my childhood through smelling each piece of it. The smell of my favorite dishes. The smell of the places I had been to. The smell of the perfume exhaled by my primary school teacher, who would always come up to me with a genuine desire to help me, looking at me like a person she knew could do more, bringing confidence. That was the look I needed. The look of an angel, as if saying, “GO MARCOS”. Go, things are under control. Although in fact nothing in life is.

I found myself remembering the first time I played soccer. I was a child, and I would be the team’s forward, without ever having played. I was afraid, but she looked at me. The teacher with the pleasant smell. She looked at me and made signals for me to go ahead. It was a kind of carte blanche so I could trust myself in the way that I needed to do it. I went on to the field, with my two crutches fitted to my arms and took a deep breath. I had bigger enemies than people could imagine. My friends wanted me to play, but my fears were going against me in that moment.

When the game started, I began to run. Today, looking back in perspective, I was something like an out- -of-control Forrest Gump. But without the legs, since those little crutches took their place. I ran without fear that anyone would see me. I ran beyond my humble capacities. When I was running, I sensed that the capacities and limitations I thought were real, were actually in my head.

The teacher looked at me, and I accepted, finally, that I was ready for the game. The ball started rolling and I chased it like a professional in the middle of a deciding game in a world championship. I felt like the world had stopped to look at me. And the magic that accompanied me in that moment would be hard to explain to anyone, as it brought some luck. A little prayer, perhaps. My teacher’s cheering. My hidden desire to be able to impress everyone. And, above all, to leave there telling myself that I could.

I could.

When the ball finally stopped in front of me, everyone looked at each other. Quickly, without thinking about the movements, without calculating what I would do next, I dribbled once, dribbled twice, and just got in front of the goal. That goal seemed gigantic. That is to say, what wouldn’t seem gigantic for that boy on two crutches? It was rather unlikely that I could kick the ball inside it. The goalie seemed much taller up that close. He was a giant in front of a gate. At that moment, I chickened out. And then I felt it. Once again I could smell the wet ink on the wall of the field where we were making our debut. And there I was, running towards the goal. The ball and me. I tried to think, but a child feels more than he thinks. A child is pure instinct. A child was what I was, and what I would be, even after years of experience. Someone who don’t see limits in dreams, who is bigger than anyone can imagine. And I realized I was capable of making that goal. As if the world was televising that event, as if the stands were full, with all spotlights over me. I glowed. And, glowing, I understood that I could be much bigger than I was. I understood I didn’t need to believe in limits. And I needed to make that happen.

When we want to prove something to ourselves, the internal fight is very big. I had already faced my demons from very early stages of my life. Since I was a child, I knew I would have to confront that voice in my mind that always try to prove the opposite of what I believe. However, there was no limit in the scene above; nothing I couldn’t do. I saw the goal. I was able to feel the net shaking, even before shooting the ball. However, in real life, when we think too much, we allow monsters to destroy our dreams. And that’s what happened to me that time.

At that moment, a boy from the other team came forward, just like that, out of nowhere, in front of me. It was as if he knew that he could fly away me and my dreams. As if he knew that his threatening presence would make me sick and he would be able to upset me. It was as if his smile could stop me. And he was able to get the ball. With- out hesitation. Without embarrassment. Without pity.

I didn’t want mercy. I didn’t want sympathy. I remembered all the times that I fought against that. All the times my mother had confronted prejudice so I would be able to be treated like an equal at school; how she had persisted until she found one that would take me in and wouldn’t treat me differently.

What was I complaining about? By acting like this, he was just showing he saw me as an adversary at his level. Isn’t that what I wanted? To be treated like a person with- out a disability? I thought about how he could have made it easy for me. Perhaps, had he made it easy for me in that big, decisive game, things now would not be the way they are. I didn’t want easy things that sprang out of pity. I wanted challenge, courage. I wanted people who would look at me and take on a challenge.

For better or worse, I would achieve that. And unconsciously he made me become stronger. They say suffering molds people, that everything we go through in life gives us strength, if we are able to get out of the victim role and transform ourselves.

That was going to change me.

But hold on. I was still a child. Children don’t see that far ahead, nor do they have such elaborate thoughts. What I wanted was to win the game so that he would see what he had gotten himself into. I wanted to win. And my victory went beyond anything else. Though his legs were longer than mine, his determination wasn’t as big as mine.

Armed with an absurd willpower, I used a resource that was available to me at that moment. Without thinking about it, I used the crutches to my advantage. I got the ball back, in a historic dribbling. Some players have seen the scene, others haven’t, but the truth is that I hit the boy’s shin with my crutch. I didn’t understand much about ethics at that time, but I did know one thing: I was going to make up my own rules. And if he was going to use his long legs, I was going to use my crutch. You bet I would!