Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Icon Books

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

'A spicy and original romp through Russian history' ROBERT SERVICE 'Poignant, comical, and in the best sense disturbing'PAUL FREEDMAN, AUTHOR OF TEN RESTAURANTS THAT CHANGED AMERICA 'This wickedly delicious tale uncovers the secret, gustatory history of the Kremlin and will leave you begging for seconds' DOUGLAS SMITH, AUTHOR OF RASPUTIN: FAITH, POWER, AND THE TWILIGHT OF THE ROMANOVS What's Cooking in the Kremlin is a tale of feast and famine told from the kitchen, the narrative of one of the most complex, troubling and fascinating nations on earth. We will travel through Putin's Russia with acclaimed author Witold Szabłowski as he learns the story of the chef who was shot alongside the Romonovs, and the Ukrainian woman who survived the Great Famine created by Stalin and still weeps with guilt; the soldiers on the Eastern front who roasted snails and made nettle soup as they fought back Hitler's army; the woman who cooked for Yuri Gagarin and the cosmonauts, and the man who ran the Kremlin kitchen during the years of plenty under Brezhnev. We will hear from the women who fed the firefighters at Chernobyl, and the story of the Crimean Tatars, who returned to their homeland after decades of exile, only to flee once Russia invaded Crimea again, in 2014. In tracking down these remarkable stories and voices, Witold Szabłowski has written an account of modern Russia unlike any other - a book that reminds us of the human stories behind the history.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 501

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Acclaim for What’s Cooking in the Kremlin

“If you want to understand the making of modern Russia, read this book.”

—Daniel Stone, bestselling author of The Food Explorer

“A riveting account of a uniquely sumptuous cuisine prepared in often grotesque and dangerous settings.”

—Paul Freedman, author of Ten Restaurants That Changed America

“As a chef and the daughter of Soviet Jewish refugees, I have experienced a lifelong fascination with, mingled with repulsion toward, the food on my ancestral table. What’s Cooking in the Kremlin gracefully captures this perpetual tension—it is what inevitably arises when an extraordinary cuisine becomes a weapon deployed against the very people who’ve made it.”

—Bonnie Frumkin Morales, author of Kachka: A Return to Russian Cooking

“[This book] is more important now than ever with the Ukraine conflict. The chapter about the famine in Ukraine was especially touching for me, as my grandparents and great-grandparents lived through it. You won’t be able to put it down!”

—Tatyana Nesteruk, author of Beyond Borscht

“By turns poignant and playful . . . [with] engaging stories and oral histories given by cooks who survived the vagaries of the Kremlin’s whims and who toiled through the great afflictions of collectivization, the Siege of Leningrad, the Chernobyl disaster, and more.”

—Darra Goldstein, author of A Taste of Russia

“This book will make your mouth water. Witold Szabłowski’s delicious dive into Russian imperial history comes complete with recipes for Stalin’s favorite Georgian walnut jam, the blockade bread that people ate during the World War II Siege of Leningrad, and the turkey in quince and orange juice served to Winston Churchill and Franklin D. Roosevelt in Yalta in 1945. . . . [It] explores how the way to the famed Russian soul has always been through the collective stomach.”

—Kristen R. Ghodsee, author of Everyday Utopia

ABOUT THE AUTHOR AND TRANSLATOR

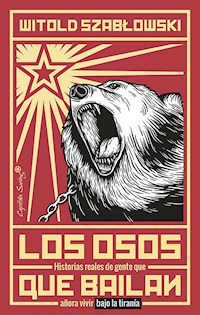

Witold Szabłowski is an award-winning Polish journalist and the author of How to Feed a Dictator and Dancing Bears. When he was twenty-four he had a stint as a chef in Copenhagen, and at age twenty-five he became the youngest reporter at one of Poland’s largest daily newspapers, where he covered international stories in countries including Cuba, South Africa, and Iceland. His features on the issue of migrants flocking to the EU won the European Parliament Journalism Prize; his reportage on the 1943 massacre of Poles in Ukraine won the Polish Press Agency’s Ryszard Kapuściński Award; and his book about Turkey, The Assassin from Apricot City, won the Beata Pawlak Award and an English PEN award and was nominated for the Nike Award, Poland’s most prestigious literary prize. Szabłowski lives in Warsaw.

Antonia Lloyd-Jones has translated modern fiction, reportage, poetry, and children’s books by several of Poland’s leading authors. In 2019 her translation of Drive Your Plow Over the Bones of the Dead by Olga Tokarczuk, winner of the Nobel Prize in Literature, was shortlisted for the Man Booker International Prize. She is a former cochair of the UK Translators Association.

Copyright © 2021 by Witold SzabłowskiTranslation copyright © 2023 by Antonia Lloyd- Jones

Page 358 constitutes an extension to this copyright page.

First published in Poland as Rosja od kuchni: Jak zbudować imperium nożem, chochlą i widelcem by Grupa Wydawnicza Foksal, Warsaw

Map by Cyprian Zadrożny

Published in the UK in 2023 by

Icon Books Ltd, Omnibus Business Centre,

39–41 North Road, London N7 9DP

email: [email protected]

www.iconbooks.com

ISBN: 978-183773-019-3

eBook: 978-183773-021-6

The right of Witold Szabłowski to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Printed and bound in the UK

Designed by Jessica Shatan Heslin/Studio Shatan, Inc.

The recipes contained in this book have been created for the ingredients and techniques indicated. The Publisher is not responsible for your specific health or allergy needs that may require supervision. Nor is the Publisher responsible for any adverse reactions you may have to the recipes contained in the book, whether you follow them as written or modify them to suit your personal dietary needs or tastes.

In memory of Leokadia Szabłowska

CONTENTS

Preface

Introduction

I.

The Last Tsar’s Chef

II.

Lenin’s Cook

III.

The Great Famine

IV.

A Meeting in the Mountains: Stalin’s Eating Habits

V.

Beauty and Beria: Stalin’s Cook and His Wife

VI.

A Baker in Besieged Leningrad

VII.

Exhumation: Cooking in Wartime

VIII.

The Feast at Yalta

IX.

Gagarin’s Cook

X.

The Kremlin Chef

XI.

The Cook from the Afghan War

XII.

The First Return of Viktor Belyaev

XIII.

The Fairy-Tale Forest: Cooking at Chernobyl

XIV.

The Second Return of Viktor Belyaev

XV.

Wild Boar Goulash, or the Soviet Union’s Last Supper

XVI.

The Sanatorium Cook

XVII.

Crimean Tatar Cuisine

XVIII.

The Third Return of Viktor Belyaev

Afterword

Acknowledgments

Bibliography

Photo Credits

Preface

As I write these words, it has been several months since Russia unleashed its cruel war against Ukraine. Unfortunately, for that very reason this book has become extremely topical. To research it, I traveled the length and breadth of Russia, Ukraine, Belarus, and several other former Soviet republics. I spoke to some unusual cooks, including Viktor Belyaev, the head of all the Kremlin kitchens, who had a major heart attack soon after Vladimir Putin’s accession to power and had to retire; the cooks responsible for feeding the frontline troops during various conflicts instigated by Russia; the cooks who worked at Chernobyl after the nuclear disaster; and people who survived the Great Famine, cold-bloodedly planned and executed by Stalin.

Today I couldn’t have done the research for this book, because I wouldn’t be allowed to enter Russia or Belarus. And if I were, I’d soon be arrested for writing the sorts of things you’ll read here. In fact, in the course of my research I had to explain myself several times to the police, and I was once interrogated by the Russian special services. I managed to complete the work only because it never occurred to any of Putin’s state agencies that it’s possible to show the mechanisms of power— Putin’s and his predecessors’—through the kitchen.

I have no doubt that it is possible. Just as I’m quite sure that in the present conflict too, the cooks on both sides are stretching their skills to the limits to fill the stomachs entrusted to their care. These are people like thirty-five-year-old Natalya Babeush from Mariupol, Ukraine, who has a warm and gentle smile. Before the war she worked as a high-pressure-boiler engineer at the Azovstal steelworks, where her husband also worked. When the war began and the Russians were approaching the city center, she and her husband moved into the steelworks, which has hundreds of underground passages and shelters. It was easier to hide out there than at home during the Russian attack and subsequent siege of the city. Natalya and her husband ended up in a bunker where more than forty people were sheltering, including eight children. The youngest was only two.

While there, Natalya quickly became a cook, making meals for everyone on a primitive stove, using a scorched saucepan, the only one she had. Soon she was doing something that seems to come naturally to most cooks—the ones featured in this book, and the world over: she raised morale. She joked, she roped people in to help, and when she found some paper and crayons, she organized drawing contests for the children. She helped others to endure the hell of the siege. The smallest children couldn’t say her name properly, so she told them to call her Auntie Soup. And that’s how she’s remembered: Auntie Soup from the Azovstal works.

Natalya and her husband were successfully evacuated a couple of weeks before the defenders of Azovstal surrendered on the orders of President Zelensky and the Ukrainian chief of staff. They had spent more than two months underground. In that time many of their friends had died. Natalya still weeps whenever she talks to journalists. But she’s surprised to be asked for a recipe—what was on the menu in the Azovstal bunker? One or at most two cans of Spam, immersed in 30 liters (8 gallons) of water. (Natalya was able to get water from the plant’s industrial tanks.) That’s all they had to eat at the besieged steelworks, so everyone was permanently hungry. Every day, every second could have been their last.

The people who got out of there alive had various culinary requests. Some of them wanted pizza, while others longed for sushi or a juicy steak. The first thing Natalya ate was a slice of bread and butter—just like the women who survived the Great Famine, who still think of a plain piece of bread as the greatest treat they can imagine.

So people’s tastes don’t change when they’ve been to hell and back. Nor does politics change in Russia, the country that has built its power with a knife and fork—and famine. As I write this, Putin is trying to pressure other countries into giving him a free hand in the war against Ukraine by threatening to prevent ships carrying Ukrainian grain from leaving their ports. If the ships don’t sail, many countries in Africa and the Middle East will risk experiencing famine. Russia is deliberately blackmailing the world: either you meet us halfway, or more people will die of hunger, not just in Ukraine but also the world over. This book explains why it’s in Russia of all places that a regime could come up with such a diabolical idea.

But there is a glimmer of hope. Following each of Russia’s “interventions”—Putin never refers to the war in Ukraine as a war but insists on calling it “brotherly intervention”—the blinders imposed by propaganda have fallen from the eyes of the Russians. That’s what happened to Mama Nina, the cook you’ll meet in the chapter about the war against Afghanistan. Only there did she realize she’d been conned by the politicians, and millions of Soviet citizens came to have the same realization.

I am certain the same thing will happen this time too. By attacking Ukraine, Putin has made a major error, one that might cost him his power—or even his life. For many years it has not been the people in the streets who have overthrown Russia’s dictators but palace coteries, including members of the staff: bodyguards, cooks, and chauffeurs. Perhaps there’s already a cook at the Kremlin who’s going to add a few drops of poison to Putin’s soup, whether it’s borscht, shchi, or ukha.

I hope one day I’ll have the chance to ask them what kind of soup it was.

Introduction

All at once the smells of gasoline, fruit wine, and partly digested fried fish hit my nostrils. The gasoline was coming from a cutter that had headed out to sea around an hour ago, and the wine and fish must have been from the stomach of the drunken janitor who had thrown up under my window. There I lay in bed, still half-asleep, listening to the roar of the Black Sea and watching some policemen representing the Republic of Abkhazia—a self-proclaimed orphan of the Soviet Union recognized only by Russia—as they searched my room. In the doorway stood the flustered manager of the holiday resort where I was perching for the night, repeating, not exactly to me and not exactly to the policemen, “Not meant to be here. I don’t know how he got here.”

He was telling the truth. He didn’t know.

So for the second or third time I explained that I’d arrived late at night, that the drunken janitor—the same man who would later sing bawdy songs in Russian, and later still vomit under my window—had let me in and said I should go to bed, that we’d settle up in the morning.

When the police found nothing suspicious on me, it started to dawn on the manager that he’d made a mistake and set the functionaries on an innocent man. Luckily the policemen let it drop. They made some jokes, took a few Russian rubles off me for a cup of tea, and were gone.

I was left with the manager, who was feeling pretty stupid. He made coffee in a small pot, first for me and then for himself, and we drank it in silence while he wondered whether to try to placate me. He decided to give it a try and offered me a glass of chacha—a very strong spirit made of grapes—to go with my coffee (I refused it, because it was seven in the morning). Then out of the blue he asked if I knew where we were.

“In New Athos, in Abkhazia,” I replied, yawning.

But the manager violently shook his head, saying that it was true, but not entirely. And that I was to follow him. So we drank up our coffee, and off we went. First he unlocked a chain hanging on a gate, then he led me through a secret tunnel that ran under the street and a few dozen yards beyond. All of a sudden, we were in a garden of paradise. I’m not exaggerating. Around us grew both pine trees and palms; the milk from coconuts that had fallen and cracked against the asphalt was flowing down the path. Two beautiful black horses were licking it up, and two more, bays, were grazing a short way off. As we walked along the path, brightly colored birds chased one another between the bushes.

Beyond all this, the path began to lead uphill.

On the way we passed a sign that read PROPERTY OF THE PRESIDENT OF ABKHAZIA—NO ENTRY. Beside it stood two agents who were there to guard the grounds, but the manager waved to them and they let us through. Green-and-brown lizards raced underfoot, and bird after bird screeched overhead. Finally the asphalt ended, and we were standing outside a small green house on a hillside. The view was stunning: palm trees, forest, and the turquoise sea looming below.

“This place is top secret. It used to be Stalin’s summer dacha,” said the manager. “He came here on vacation every year toward the end of his life. The house where you slept was built later on, but it’s also part of his estate.”

Suddenly it all made sense. For decades this place had been accessible to only a small number of people. Stalin had died, the Soviet Union had collapsed, but no one had rescinded the order to keep it as hidden as possible from the eyes of outsiders. The cottages were probably rented to tourists illegally—maybe even Stalin’s villa was rented out. Who knows—in a nonexistent country, anything’s possible. But tourists from Russia, a common sight here, are one thing, while someone from Poland is quite another. That’s why the manager panicked and called the police.

I started wondering how I could see inside the dacha. And the manager seemed to read my mind.

“I don’t have the key.” He spread his hands. “But my colleague has it. If you’d like, I’ll ask him to let us in this evening.”

So I spent the day touring the sights of New Athos, and then went back. The manager was already waiting with several other men. One of them was named Aslan; tall and graying, he was the one who had the key, and in the days of the Soviet Union he’d recorded conversations with the people who’d worked at Stalin’s dacha. He let us in and told us step by step how it had been built, when exactly Stalin had arrived here, in which room and on which bed he’d slept.

Meanwhile, the other men made a bonfire and started to cook lamb shashliks. They put raw onion on some plates as well as adjika, a sauce for the meat made of hot red peppers, garlic, herbs, and walnuts. They also poured chacha—now was the right time to drink it. They all worked here on the dacha grounds: one was the gardener, another the watchman, and a third looked after the horses. They were old enough to remember the bloody war that had erupted in 1992, following the collapse of the USSR, when—with Russia’s help—Abkhazia had broken away from Georgia. We raised a toast to our meeting, we drank, and I wondered how to ask them what they thought about the war and what it had brought to their quasimini-country. Luckily the manager read my mind again.

“Russia, Georgia, what a pair of fuckers,” he said, chasing the chacha with watermelon. “Both of them are only after our beaches and our money. We shed blood, and that just makes things worse.”

The others nodded in agreement.

After the war Abkhazia separated from Georgia, but though once rich—it was known as the Soviet Côte d’Azur—the country came to a complete standstill. The only things they live on here are mandarin farming and Russian tourists. Because no one except Russia has recognized their statehood, hardly anyone but Russians ever comes here; within the mountain landscape, the richly decorated buildings are now buried in the undergrowth.

“Life hasn’t been good since Stalin’s day,” the manager went on, as his pals poured us each another glass of chacha. “He understood this land. He ate our bread, he ate our fish, he ate our salt.”

The others nodded again.

“Stalin was like us. He ate the same things as the ordinary people,” said the man who cared for the horses. “Over there, behind the dacha, is his kitchen. My grandfather worked there as a servant, he told me.”

We drank up again, and the chacha started singing in my head. As the shashliks roasted on the open fire, I went to take a leak. I chose a spot just behind Stalin’s kitchen, and on my way back I peeked inside through the window. As in the dacha, everything there was original—the burners, the floor, the table, even the pots and stools. I began to wonder who the cook had been who’d worked here. What had he made for Stalin? Had he wanted to run away from this place, or had he stood beside the Sun of Nations and bathed in his warmth?

It was just then, feeling slightly tipsy, that I first had the thought that I’d like to know if Stalin really did eat like “the ordinary people.” If so, then why? And if not, then why did they think he had?

So that was how, on a warm evening around ten years ago, the idea for this book was born.

It spent a few years marinating inside me, and once I finally got down to some serious work on it, I traveled throughout several of the former Soviet republics. I talked to the chefs of Communist Party general secretaries, cosmonauts, and frontline soldiers, and to cooks from Chernobyl* and from the war in Afghanistan. I soon discovered that Stalin hadn’t eaten like the average Abkhaz at all, nor like the average Soviet citizen. And along the way I discovered several other culinary secrets— both his and his successors’.

In this book you will learn how, when, and why Stalin’s cook taught Gorbachev’s cook to sing to his dough. How Nina, a cook during the war in Afghanistan, forced herself to think about something pleasant in the hope of imparting her good mood to the soldiers. How in Chernobyl, a few weeks after the catastrophe, a competition was held for the best canteen, and who won it.

You’ll read about Stalin’s food tester, who fought an unequal fight against the tyrant and his cronies in an effort to save his wife’s life. You’ll also find a recipe for the first soup to have flown into outer space. And for pasta with turtle doves, eaten by the last tsar, Nicholas II. You’ll find out why Brezhnev hated caviar.

And you’ll read about people who had nothing to eat at all: in Ukraine, when Stalin tried to break its back by starving its citizens, and during the siege of Leningrad.

But above all you’ll see how food can be a tool for propaganda. In a country like the Soviet Union, every pork chop fried and dished up in every canteen and restaurant from Kaliningrad to the Arctic Circle, from Kishinev to Vladivostok, was of service to propaganda. What the general secretary of the Communist Party ate and what the ordinary citizen ate were political. Just as the USSR did for decades, Russia still feeds its people on propaganda.

It’s no accident that Vladimir Putin, grandson of the cook Spiridon Putin, is in charge there. You’ll read about both of them in this book.

I’m told that these days you can visit Stalin’s dacha in New Athos legally—you just have to buy a ticket for around fifteen rubles. But as I learned from friends who went there a few years after I did, there’s still no entry to the kitchen and the door is locked.

This book aims to unlock it.

* In this book, the name “Chernobyl” is used historically to designate the site of the nuclear power plant where in April 1986 one of the reactors exploded, causing a major disaster. In the days of the Soviet Union, the name of the city was spelled in its Russian form, “Chernobyl,” though now, as a city in Ukraine, its name is spelled in Ukrainian, “Chornobyl.” As the story of the cooks that is told in chapter XIII is about the immediate aftermath of the 1986 disaster, the Soviet-era name is used here.

What’s Cooking in the Kremlin

I

The Last Tsar’s Chef

She’s in a neatly pressed suit and her hair is dyed blond. She has invited me to her apartment because her legs ache and she prefers not to go out, but for the past two hours she’s been keeping me at a distance. We’re sitting in the living room, having tea served from a samovar and some extremely stale cookies.

All her life, Alexandra Igorevna Zalivskaya has worked at an institute of higher education, and has developed a suspicion of others that’s typical of Russian state organizations; to let anyone come close, she must first form an opinion of them. And that takes time. So she spends two hours telling me about her great-grandfather Fyodor Zalivsky, who worked in the kitchen of the last tsar, Nicholas II; she doesn’t remember him, but he left the family a souvenir cup and a photograph of the tsar and his wife. And every time, as if reading from a book, she says, “His Highness Nicholas II,” never just “the tsar,” and if she’s talking about Nicholas, his wife, and their five children it’s “the holy imperial family.” She watches to see how I’ll react. Because to a Russian, a Pole is always a bit of an enigma: we’re sort of similar, but we give things quite different names and don’t understand them in the same way. She knows I want to ask her about a friend of her great-grandfather’s, the tsar’s last chef, Ivan Kharitonov. She also knows that Kharitonov’s descendants have refused to give me an interview. Mrs. Zalivskaya has to sort it all out in her head.

Ivan Mikhailovich Kharitonov

Eventually something falls into place: some algorithm in her mind decides that although I’m a Pole I’m not too bad, and she can trust me. And something happens that I will experience over and over again in Russia. Mrs. Zalivskaya takes two shot glasses and a bottle of Moskovskaya vodka from the minibar and says that’s enough chatting here, let’s go to the kitchen. And in the kitchen, by applying some special magic of her own, in under fifteen minutes she has covered the table in zakuski, or hors d’oeuvres: pickled mushrooms, pâté, a macédoine (if you don’t know what this is, please read on patiently), the pickled gherkins and sauerkraut that are standard fare on every Russian table, Olivier salad (also known as stolichny salad or simply “Russian salad”), and plenty of other little dishes that she must have had ready long before my arrival. But first she had to form an opinion of me before she could invite me from the living room into the soft underbelly of every Russian home, where favorite guests are received and where a person is as open as they can possibly be.

“Do start with the pâté, Witold Miroslavovich,” she says. “It’s one of my great-grandfather’s original recipes, straight from the tsar’s kitchen. In my family it’s always made like that for Easter.”

So I help myself to pâté, a finger-thick slice, first because I like it, and second to please my host. I pile some gherkins on top. We raise a toast—to our meeting, to friendship—and moments later my taste buds are enjoying a soft meaty substance just like the kind enjoyed by tsar Nicholas II and his family, until the Bolsheviks put them up against a wall and shot them.

1.

The best place to start the story of the tsar’s most loyal chef is at the end, on the last night of Kharitonov’s life. So let’s begin like this:

He made them supper, they crossed themselves, they ate.

It wasn’t the first time that Ivan Mikhailovich Kharitonov, a portly forty-eight-year-old with slicked-back hair, had had his hands full. Ever since the Bolsheviks had imprisoned the former tsar and his family in 1917, he had been the only chef to stay with them. Of the hundreds of people who had worked at the court before then, the five most loyal had remained, including Lyonka Sednev, the kitchen boy. Many times the Bolsheviks told them they should abandon the tsar and save their own lives, but they always refused. As the head of the group that guarded and subsequently shot the workers recalled years later: “They declared that they wanted to share the fate of the monarch. We had no right to forbid them.”

But that last evening the Bolsheviks sent the underage Lyonka to the city. They told him he’d be met by his uncle, who had also worked for the tsar.

Though Lyonka had no way of knowing, by then his uncle had been dead for several weeks.

Kharitonov had known the tsar since early childhood; it was customary at court for the Romanov children to play with the servants’ children, and Nicholas and Ivan, whose father had served Alexander III, were almost the same age. Famous for his unemotional child-rearing, Alexander wanted his children to be familiar with the so- called simple life.

But the time for games had soon ended. At the age of only twelve, Ivan Kharitonov had become a kitchen boy. Through hard work, persistence, and talent, his father had risen from an orphan raised in a children’s home to a senior position at court, and he had been appointed to the nobility by the emperor. It was he who had advised his son to build a culinary career. He had arranged for him to go to France, where the young Kharitonov became a master chef, learning from the world’s best.

But under arrest in Yekaterinburg, where the Bolsheviks had imprisoned the former tsar, it was all meaningless. Since the tsar’s abdication, the quality of his food had steadily been lowered, and not even the best chef could do anything about it. He could only make sure it happened as gently as possible. And since a master chef can cope in any circumstances, Kharitonov achieved mastery in this too.

That evening they had supper at eight, after which the former tsar and tsarina played bezique, their favorite card game and their way of killing time in prison. Meanwhile, in the commandant’s office their guards prepared six pistols and eight revolvers. The tsarina went to bed at half past ten. She still managed to devote a sentence in her diary to Lyonka, the kitchen boy: “We’re wondering if we’ll ever see him again,” she wrote with concern, because just as Kharitonov had grown up with Nicholas, Lyonka was the favorite companion of their only son, the tsarevich Alexei.

She was right: they never saw the boy again. The entry about the kitchen boy was the final one in her diary.

2.

“The tsar’s entourage consisted of nothing but remarkable people,” Mrs. Zalivskaya tells me between a pickled mushroom and another shot of vodka. “And just as the Romanovs were a dynasty, so there were whole dynasties of cooks, pastry chefs, and waiters too. It seemed that however poorly people lived in Russia the tsar would never know hunger, so the fathers trained their sons and daughters, to be sure they’d always have work. My great-grandfather Fyodor worked there because his father had trained him; I don’t know his first name, but I know poverty drove him to Saint Petersburg from near the city of Suzdal. But there were others who had worked there since the days of Catherine the Great. My great-grandfather was friendly with the pastry cook Potupchikov, for instance, whose family had apparently been with the tsar for two hundred years. Potupchikov taught him to serve frozen strawberries flavored with lemon juice, almonds, and violet petals.”

There were more than twenty pastry chefs, responsible for the cakes and also for the fruit, the nonalcoholic drinks, and the rolls that were a favorite of Alexandra Fyodorovna, wife and great love of the last tsar of Russia. The man in charge of them was the baker, Yermolaev, whose arms were shaved to the elbows and who moonlighted as an actor at one of the Saint Petersburg theaters.

“My great-grandfather didn’t like the tsarina,” says Mrs. Zalivskaya. “She was a German, she spoke Russian badly and treated the servants badly too. She put ideas into the tsar’s head and introduced Grigori Rasputin to the court, and that was the start of all the trouble that finally led to them shooting the Romanovs. As you know, there were lots of scandals involving Rasputin, and he was even accused of an affair with the tsarina. But my great-grandfather never had a bad word to say about the tsar. He always said he was a good man. Too good to rule Russia. What does ‘too good’ mean? He was very sensitive, he took everything personally. The way things were in those days, Russia needed somebody much tougher.”

The alcohol department, with a staff of fourteen, was responsible for stronger drinks, including brewing kvass. In his youth the tsar liked to drink a lot—his diary from those years is full of juvenile games with alcohol playing a leading role. After ascending the throne he settled down, but even as an adult he would drink a few glasses of port with dinner, and on his travels, a glass of strong Polish plum vodka that his viceroy sent from Warsaw.

Around 150 people were employed in the typical kitchen that prepared meals for the imperial tables, ten of whom cooked for no one but the tsar, his family, and their private guests. Four cooks specialized in roast meat, and four more—including Ivan Kharitonov—in soups. Apart from the specialists there was a whole host of apprentices, transferred on a daily basis from sponge cakes to sourdough, from sourdough to aspic, and from aspic to the team that decorated the dishes. In those days it was one of the world’s two or maybe three best kitchens.

Let’s take a look at a standard breakfast menu. On October 10, 1906, the imperial family was served cream of asparagus soup, lobster, leg of wild goat, celery salad, peaches, and coffee. On September 10, 1907, they were served pearl barley soup (with pickled gherkins, carrots, and peas), potato pancakes, salmon pâté, roast beef, chicken breast, pears in sherry, and a cranberry tart with sugar.

The lunches were just as lavish. A typical meal on May 28, 1915, a year after the start of World War I, was like this: fish soup, zander, roast meat, salad, vanilla cream. On June 26, 1915: pâté, trout, dumplings, roast duck, salad, ice cream. December 30, 1915: fish soup, dumplings, cold ham, roast chicken, salad, ice cream.

Then there was afternoon tea, with cookies and cakes in the leading role, and supper. The tsar took his meals quite late: breakfast was usually at one p.m. At five p.m. the entire family assembled for tea—a habit introduced by the tsar’s wife, Alexandra Fyodorovna, who as a granddaughter of Queen Victoria had been brought up at the British court. Dinner was at around eight in the evening, and supper often well past midnight.

But despite this richly laden table, sometimes the tsar ate nothing but an egg or two, and his wife would eat only some vegetables. Both of them watched their figures, and Nicholas weighed himself several times a day.

“They threw away a great deal of food,” says Mrs. Zalivskaya, spreading her hands. “But he was the tsar. He couldn’t just be served two eggs for breakfast. The appropriate ceremony had to be observed.”

If Nicholas did allow himself to eat a little, his favorite dish was pasta with turtle doves.

In Nicholas II’s day the maître d’hôtel—the man in charge of the imperial kitchen and dining staff, responsible both for what was served and for the cooks and the waiters—was Jean Pierre Cubat. Ivan Kharitonov had met him earlier in France. For Kharitonov he was a mentor, but also a friend with whom he corresponded and shared memories of vacations in Crimea.

Mrs. Zalivskaya forces me to drink another toast—to Polish-Russian friendship—and to have another slice of pâté. Then I force her to drink in memory of her late great-grandfather, may he rest in peace.

“My great-grandfather never imagined he’d become a first-class chef,” she tells me, wiping her mouth after the toast. “He was the son of a second-class cook, and repeating his father’s journey was quite enough for him. Cubat the Frenchman gave up working for the tsar in 1914, when World War I began. At a time of unrest he preferred to go home to his family in France. But his place was immediately filled by another Frenchman, Olivier.”

(This Olivier is sometimes mistakenly credited with creating the famous Russian vegetable salad. In fact, it was invented by another Frenchman of the same name, but half a century earlier.)

The Frenchmen raised the imperial cuisine to such a high standard that it looked as if no Russian cook would ever be maître d’hôtel at court.

“Kharitonov aspired to it,” says Mrs. Zalivskaya. “Everyone at the court knew that, including my great-grandfather. But they were all sure that any new head of the imperial kitchen would be a Frenchman. The court cuisine was greatly influenced by French cooking, and it was quite natural that it had to be the responsibility of someone from France. So no one expected Kharitonov to become the maître d’hôtel, or that it would happen in the most dramatic circumstances imaginable.”

3.

Historians are pretty much in agreement that Nicholas II was a good man but a lousy tsar. And considering he had to deal with the greatest crisis in the entire history of the Romanovs, it’s no wonder he couldn’t cope with it. According to the old Russian calendar, he was born on May 6, the day when the Orthodox Church commemorates Job—the old man on whom God inflicted all the misfortunes in the world—and from his early years the tsar often said it was no accident. (Nor was it by chance that Leo Tolstoy called him “a pathetic, weak, and stupid ruler.”)

His coronation was a disaster. On May 26, 1896, half a million Russians gathered at a parade ground in Khodynka because they had been promised free food and commemorative cups. When the stalls were opened in the morning, the crowd rushed forward, trampling over two thousand people, of whom more than a thousand died. That same evening, as if nothing had happened, the tsar danced at a ball given in his honor by the French ambassador.

The Russians never forgave him. The rift between the tsar and his subjects began on that very day, and from year to year it continued to widen.

Matters were made worse by the imperial couple’s prolonged lack of a male heir; Alexandra gave birth to four girls in a row: Olga, Tatiana, Maria, and Anastasia. But the birth of their long-awaited son not only failed to solve the couple’s problems; it also brought new ones. From early childhood the little tsarevich, Alexei, suffered from hemophilia. The tsar and tsarina sought help first from conventional doctors, then from all sorts of charlatans, faith healers, and pseudo-physicians. That was how the village preacher Grigori Rasputin appeared at their court, a man who through his sexual excesses added scandal after scandal to the already damaged reputation of the imperial family.

So the clouds had been gathering over the Romanovs for a long time when the toughest moment came, with the outbreak of World War I. Russia joined the conflict in July 1914 and took a beating right from the start. On August 20, the day of the Battle of Gumbinnen, for lunch the tsar was served patés, pork goulash, crab pilaf, and poularde stuffed with snipe and peaches.

Disaster was ever nearer.

4.

Power was slipping from Nicholas’s hands by the day. The people were tired of the ineptly conducted war. The soldiers mutinied. When in March 1917 even the State Duma turned against the tsar, Nicholas decided to abdicate.

The Provisional Government sent him to his palace at Tsarskoye Selo, where at first the Romanovs’ living standards did not change much—they were still surrounded by chefs, waiters, and stewards. The most significant change was that after the tsar abdicated, the French maître d’hôtel, Olivier, took off. Suddenly there wasn’t a single Frenchman at court to be his successor.

“Ivan Kharitonov received the title,” says Mrs. Zalivskaya. “It was the crowning achievement of his career, but a sad one: he became head of the kitchen staff of a tsar who was no longer tsar. My great-grandfather went on working at court. Kharitonov invited everyone for a glass of cognac. But it really was just one small glass: the staff working for the former tsar was to behave with dignity.”

In the first few weeks the court continued to operate in much the same way. A few days after the abdication, Kharitonov filled in the kitchen order form as follows: three apples, eight pears, six apricots, and half a pound of jam, plus a carafe of the dessert wine cherry kagor. But soon after, the government began its repressions. First the Romanovs were no longer allowed fruit, and the flowers were removed from their rooms. The budget for their food was reduced too. Later on things went further: gearing up for the legal action that the people of Russia were to bring against the tsar, supposedly Prime Minister Alexander Kerensky forbade the tsar and tsarina to sleep in the same bed; they were to spend as little time together as possible, to prevent them from preparing a common line of defense. Fortunately for them, this did not last long.

So for breakfast Kharitonov served the imperial family a healthy diet of oatmeal, pearl barley with mushrooms (1.5 rubles per portion), or rice rissoles. For dinner in this difficult period there were Pozharsky rissoles (made with minced chicken or veal) at a cost of 4.5 rubles each. For those watching their weight he made pasta rissoles, at a cost of 1.5 rubles each. And when the end of the accounting period was near—the tsar’s budget for food was calculated every ten days—to save money he served potatoes roasted in the embers, which the imperial family loved.

In late July 1917 Kharitonov began to serve the tsar macédoine, a cheap and impressive dish of finely diced vegetables or fruit, often with the consistency of aspic, which he must have learned to make in France. He made the vegetable version with carrots and turnips, then added beans and peas and seasoned it with butter. A sweet macédoine was made of diced fruit: bananas, grapefruit, oranges, strawberries, and apples, with a splash of rum or jelly, just as fruit salad is made today. By then Kharitonov was having to rack his brains to feed Nicholas and his family.

After the Romanovs had been at the Tsarskoye Selo a few months, the government decided that they should be transferred to Tobolsk in Siberia—they would have to move from a palace into the governor’s former residence. The new maître d’hôtel stopped receiving money from the state purse to feed Nicholas; from now on Citizen Romanov would have to feed himself, his family, and his retinue at his own expense.

The Romanovs were still eating fairly normally, or at least they were not going hungry. One day Kharitonov would make them borscht, pasta, potatoes, and rice rissoles for dinner; another day solyanka (sour soup), potatoes, turnip-and-ice purée; and yet another day shchi (cabbage soup) and roast piglet with rice. But from then on they would only fare worse, especially after October 1917, when the revolution erupted in Petrograd (as Saint Petersburg was renamed in 1914) and the Bolsheviks, led by the charismatic Vladimir Ilyich Lenin, took total power.

The October Revolution—the event that ultimately led to the death of the entire Romanov family—did not particularly trouble Nicholas. Many years later Vasily Pankratov, who guarded the tsar in Tobolsk, wrote in his memoirs that Nicholas became agitated only when he heard that the crowd had forced its way into the Winter Palace in Petrograd and cleaned out . . . the wine cellars. The alcohol in there had been worth more than the equivalent of five million dollars. The Bolsheviks ordered that it be poured into the Neva, and although not everyone obeyed and plenty of people managed to get drunk, much of the wine flowed off to the Baltic Sea.

The gulf between what happened in Petrograd and Nicholas II’s understanding of it shows how divorced from reality he was by then.

Meanwhile, Kharitonov had increasing difficulties buying basic produce. Nicholas was cut off from his money, and most of his property had been requisitioned by the state. So the chef had to tour the houses of the wealthy, asking them to support the imperial kitchen with donations. He often came away with nothing: many people, even those who were well off, did not support the tsarist system, especially “Nicholas the Bloody,” as the Russians called him. Others were afraid of the Bolsheviks.

“My great-grandfather followed the tsar to Tobolsk too,” says Mrs. Zalivskaya. “But there, as I’m ashamed to admit, the Bolsheviks started to brainwash him. They said there was no tsar anymore, and no magnates, that everyone was equal. And that my great-grandfather didn’t have to be a cook all his life, but could be a professor, for instance, a general, or a minister. That was typical of their nonsense, you see. We are all immune to it now, but poor Fyodor was hearing it for the first time in his life, and he believed it. He abandoned the tsar, went back to his family in Petrograd, and for a while became a militant communist. It is not for us to judge the deeds of our forebears, Witold, but I am a little ashamed of him. At any rate, the man whom I regard as a real hero is not my great-grandfather, but Ivan Kharitonov, who stayed with the tsar to the bitter end.”

5.

Following the victory of the Bolshevik revolution, the tsar and his family were forced to move again, from Tobolsk to Yekaterinburg. Here they were no longer the imperial family, but prisoners. The nooses around their necks were tightening.

They made the journey in stages, first Nicholas and Alexandra, then the children, who stayed in Tobolsk a little longer because of the tsarevich Alexei’s condition. On short notice, Kharitonov went with the second group. He wasn’t given the chance to say goodbye to his wife, Yevgenia. Until now, she and their six children had bravely followed him, but this time she was only able to wave farewell through the window. Someone suggested he should give her his gold watch, which, apart from his cufflinks engraved with the imperial eagle, was the most valuable gift he had received for his loyal service. But he just waved, thinking he’d be back soon. And if not, why worry her now?

All he left at home was a copy of the Bible with a personal dedication from the tsarina.

In Yekaterinburg the cook set about his work with great energy. Nicholas II and his relatives had home-cooked dinners once again, rather than what the Bolsheviks brought them from the local canteen. The tsar, who kept an extremely boring diary in which he loved to write about food, mentions Kharitonov’s return as follows: “June 5. Tuesday. Since yesterday Kharitonov has been preparing our meals. He’s teaching my daughters how to cook, how to knead dough in the evening, and then bake bread in the morning! Wonderful!”

Alexandra, Nicholas’s far more laconic wife, also noted Kharitonov’s return in her diary: “Dinner. Kharitonov made a pasta cake.”

So the chef tried to function just as before. But in Yekaterinburg nothing was the same anymore.

“The tsar was a prisoner, and at every step the Bolsheviks showed their disdain; even making a cup of tea involved asking the guards for permission,” Mrs. Zalivskaya tells me. “They were only given modest, soldiers’ rations to eat, and often not even those arrived.”

Once again Kharitonov tried to make up for the lack of supplies by buying on credit from local families, and often by simply begging. But he usually met with refusal. Only the nuns from the local Novo-Tikhvinsky convent supplied the Romanovs with basics like milk, eggs, and cream.

The guards often kept the former tsar and his family company at dinner. Sometimes they would dip their spoons into the soup of one of the grand duchesses and remark, “They’re still feeding you pretty well.” Soon Yakov Yurovsky, the commander of the guard, forbade the nuns from bringing eggs and cream for the prisoners. “We have been brought meat for six days, but so little that it was only enough for soup,” noted Alexandra in her diary.

6.

On July 15 something astonishing happened: Yurovsky not only allowed eggs from the convent to be served but also ordered the nuns to prepare another fifty for the next day. For whom were they intended? No one could guess.

The following day, fourteen-year-old Lyonka Sednev was sent to the city to meet with his uncle, who until recently had also worked for the Romanovs. The kitchen boy, on whom the Bolsheviks seem to have taken pity, was the only one of the prisoners at Yekaterinburg to get out alive.

The rest were woken in the middle of the night. They were told to pack and that White Army forces, the enemy of the Bolsheviks, were approaching the city. Indeed, shots had been heard all day from the Ipatiev House, where they were being detained.

“Well, we’re moving out,” said Nicholas. They crossed the courtyard, then went through a double-leaf door into the cellar. Nicholas went first, carrying Alexei, followed by Alexandra, the grand duchesses, and the servants. In the cellar the footman, Trupp, and the cook, Kharitonov, stood beside the grand duchesses.

To the end they thought they had been brought down there purely as a prelude to the move. Only moments before the execution did Yurovsky make a short speech betraying his real intentions, and then his men opened fire.

The first to die was the tsar, followed immediately by Kharitonov and Trupp. But the grand duchesses had precious gems sewn into their clothes, and the bullets bounced off them. The Bolsheviks had to finish them off with shots at close range.

The fifty eggs supplied by the nuns from the Novo-Tikhvinsky convent were provisions for the group of local peasants who were to dig graves for the Romanovs.

After the execution the assassins transported the bodies beyond the city by truck. But the site they had chosen for the burial turned out to be swampy, and the corpses kept floating to the surface. On top of that, the peasants employed to dig the graves were more interested in robbing the corpses (and fingering their intimate parts) than in helping bury them.

Yurovsky, in charge of the operation, had the corpses stripped naked. Then he secured the many precious gems hidden inside their clothes (Alexandra had a gold bracelet weighing a pound sewn into her brassiere, and the grand duchesses had plenty of large diamonds), broke their bones, and poured acid over their faces. All so that no one would ever be able to recognize the remains.

The tsar’s body was thrown on top of his cook’s, with the tsar’s ribs landing on Kharitonov’s head.

Seven decades later, in 1991, archaeologists extracted more than nine hundred bones from a pit dug next to a marsh. It took them several months to establish that they belonged to nine people.

Several more months passed before they established who was who in the grave.

The easiest to identify were the tsarina and her maid Anna; they were the only middle-aged women, and beside Alexandra’s skull was found a very modern denture that the maid couldn’t have afforded.

The skeletons were then examined by comparing the skulls to photographs. It was laborious, not least because the skull that was finally identified as that of Kharitonov had only its upper part, including the edges of the eye sockets. Either he had been shot straight in the face, or the Bolsheviks had proceeded to smash his skull to pieces.

________

“Witold Miroslavovich,” says Mrs. Zalivskaya, drinking only half a glass at a time by now because of her high cholesterol. She’s saying that this is the last one, but after what she’s about to say, we must have another drink. “There’s one thing you have to know. I was very interested in Kharitonov, because he worked with my great-grandfather and they knew each other well. I have spoken to everyone who might know something. I have read everything I can find. I’ve been to meetings with investigators and anthropologists.” At this point she pauses, because it’s a very delicate matter. “And they all say, unofficially, that what is buried today in Saint Petersburg in the grave of Saint Nicholas II, the last tsar of Russia, is in fact a mixture of bones belonging to both the tsar and his cook.”

“The cook is lying in the same coffin as the tsar?” I ask to make sure.

“So they say.” She spreads her hands sadly. “Significant, isn’t it?”

MENU

Turtle Doves and Pasta

In 2020 the Russian newspaper Komsomolskaya Pravda asked the famous chef Igor Shurupov to re- create Nicholas II’s favorite recipe, which was turtle doves and pasta. The trouble is, since the tsar’s death these medium- sized birds have become virtually extinct and are now strictly protected. Shurupov advised using pigeon or quail as a substitute.

For the dish to taste similar to that enjoyed by the tsar, one must marinate several quail overnight in vinegar, then drain them, stuff them with thin pieces of ham, and fry them for an hour and a half in a frying pan.

To go with these birds, the tsar liked to have homemade pasta made of white flour and potatoes.

The turtle doves were not shot, to save the ill- fated Nicholas II from finding pellets in them. Instead, peasants employed by the court would scatter sunflower seeds to lure the birds into an open field, then throw large nets over them and strangle them by hand.

II

Lenin’s Cook

We are not utopians . . . We know that not every laborer,

not every cook will be able to run the country from one

day to the next.

VLADIMIR ILYICH LENIN

1.

Welcome to Gorki Leninskiye, the place where Vladimir Ilyich Lenin spent the final days of his life. I know you’re particularly interested in the topic of food, so let’s go to the kitchen where the cooking was done for him—I’ve been to fetch the keys already. I’ll tell you all about Shura Vorobyova, Lenin’s cook, whom I’ve been looking for evidence of, and who for many years remained in the shadows—for who would ever have seen the leader of the world proletariat employing servants, right?

But first I’ll tell you about this place. We’re standing outside the house where Lenin came to live after the assassination attempt carried out by Fanny Kaplan. He was to recuperate here. Many of the famous photographs of him were taken here, in the park. Sorry? I didn’t hear what you said. Including the one where he’s goggle-eyed? Yes, sir, that picture of the ailing Vladimir Ilyich a few days before he died was taken in the garden of this house. But I would rather you spoke of him with greater respect, though of course I know you are a Pole; I was expecting to have a hard time with you. I know that in Poland you don’t like him and that you tell plenty of lies about him. What’s that? Syphilis?! Well, quite—you can see what I mean. No, I don’t know the relationship between bulging eyes and venereal diseases. It was Lenin’s enemies who spread rumors about his alleged shameful illnesses, but don’t forget that they were supporters of the tsar. They hated Lenin to the marrow of his bones. They’d have done anything to discredit him: accuse him of living in luxury or of sexual excesses.

But nothing of the kind really happened. Throughout his life, sir, Lenin lived and ate extremely modestly. They say his one and only true love and passion was revolution, and that makes a lot of sense. Well, please don’t say any more. Let’s start at the beginning.

On the second floor we have the telephone room, with an old telephone, and the library. A narrow staircase leads to the third floor. At Lenin’s request extra inside banisters were installed that allowed him to go up and down the stairs without disturbing the staff.

On the third floor we have Lenin’s bedroom, the dining room, the study, and the bedroom of his wife, Nadezhda Krupskaya.

In the study there’s a small desk standing in front of a wide window that overlooks the park. Some of the newspapers, books, and journals that Lenin read are spread out on the table, and there are also some envelopes and letterhead stamped with CHAIRMAN OF THE COUNCIL OF PEOPLE’S COMMISSARS. Here is the bed in which he died. Please take a few minutes for your thoughts. Ready? Let’s go on.

Vladimir Ilyich came from a family that had climbed up the ladder of the tsarist administration. His father managed to join the Russian elite, becoming head of the education department for the Simbirsk region, but financially he was a long way from being wealthy. An expression of his aspirations was the fact that—like the elite in those days—the family ate white bread, rather than the black bread that was typical for the countryside and for the poorer peasant strata. William Pokhlebkin, a pioneer of Russian culinary literature, wrote in an article about Lenin’s diet that the white bread had an impact on the rest of his life. Although the black bread might not have tasted as good, it contained lots of vitamins and minerals, which the white bread did not—but white bread was what the richer people ate, so Lenin’s father wanted to eat it too. But of course the rich men provided themselves with minerals from other sources that the Ulyanov family couldn’t afford. Lenin never made up for what he didn’t get from his bread in childhood. That’s why he was so very sick at the end of his life. This was one of the reasons he lacked the strength to pull himself together after the assassination attempt, so he died prematurely.

As a little boy, Volodya did eat regularly enough—his mother was from a family of Volga-district Germans and took great care of domestic Ordnung, including mealtimes. To the end of his life Lenin showed up on time for every meal and was very annoyed if anyone else was just a minute late. His childhood also gave him a dislike of sweets—his parents only offered them to his sisters; in those days sweets of any kind were regarded as unmanly.

But as soon as Vladimir Ilyich left home to study, he stopped eating regularly and immediately contracted a stomach disorder that bothered him, with greater or lesser intensity, throughout his life. Paradoxically, he only ate better when the tsar cracked down on him. The first time he ended up in prison, where things may have been bad for him but where he was fed regularly, his problems abated. He left prison, went back to his student-revolutionary life, and instantly started to complain of stomach trouble again.

The same thing happened when the tsar sent Lenin into exile in Siberia, to the village of Shushenskoye on the Lena. For the eight rubles he had at his disposal, he received board and lodging with a local family. Nadezhda Konstantinovna Krupskaya, a friend from the Socialist Party, came to join him; she had been exiled to Siberia too and had begged the officials to send her to the same place as Lenin. It’s hard to say what he thought about her arrival, but it definitely didn’t please his family. His sister Maria couldn’t bear Krupskaya. She thought her ugly and intrusive, with as much charm as a herring; she thought her brother deserved someone much better.

But Lenin didn’t complain; he valued the great support he had in Krupskaya for revolutionary matters, though to the end of his days he often said that he had never met any woman capable of reading Das Kapital, understanding a railroad timetable, or playing chess well.

So thanks to the tsar, Lenin and Krupskaya had a three-year “vacation” in Siberia. And for the first time since leaving prison he had regular meals, three times a day, and it was good, healthy, fatty Russian cooking: pelmeni, ukha (fish soup), shchi (cabbage soup), and rassolnik (cucumber soup), as well as baked fish, which he often caught himself, and the meat of game animals that he often hunted himself. Suffice it to say that when Krupskaya’s mother came to visit them in exile, at the sight of them she exclaimed, “But you’re in fine form!”

Krupskaya’s mother would accompany them for many years. One of the first things she did upon arriving in Siberia was to establish a kitchen garden, where she and her daughter planted tomatoes, cucumbers, chives, dill, onions, and garlic. In winter they pickled the cucumbers. This added the ideal variety to their good Siberian peasant diet. Lenin never ate better in his life.