Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Parthian Books

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

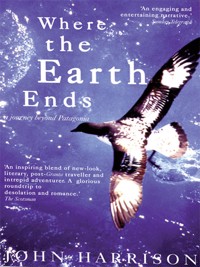

'My great grandfather and grandfather sailed the Horn, in steam and diesel, out of Liverpool. I was the first generation not to sail the Horn or fight a war. Instead, I would go to the end of the world, beyond Patagonia, to Tierra del Fuego. I would do more, I would see the Horn and find lost tribes. The child in me could go even further and sail the waters of Coleridge's albatross and enter the watercolours' blue horizons of my first novel, and sit on Robinson Crusoe's imaginary shore. I had imagined these places; they must exist. All I had to do was look for them.'

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 514

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2012

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Contents

Title Page

About John Harrison

Dedication

1. Patagonia

2. Tierra del Fuego

3. Antarctica

4. Punta Arenas

5. Last Hope Sound

6. The Long Pacific Shore

Coda

Acknowledgements

Copyright

Where the Earth

Ends

John Harrison

John Harrison was born in Liverpool to a seafaring family who made a hobby of rounding Cape Horn. He’s now done it fourteen times, and breaks it up with tripsto Antarctica and remote corners of South America. Home is in Cardiff, and shared with his partner Elaine. He has recently walked a thousand kilometres alone through the High Andes for two new books on Peru. He is a fellow of the Royal Geographical Society.

To Elaine,

for believing

xxxx

1. Patagonia

A Landing

December. Three in the morning. The plane shuddered down through the turbulence in the low cumulus and banked. The most southerly town on Argentina’s mainlandcame up out of the black: Rio Gallegos. The plane abruptlyfell another three hundred feet and I could see down the narrow aisle and over the pilot’s shoulder, and watch theearth saucer back and forth, trying to dodge our outstretched wheels. In all the earth this was the last continentalland which mankind reached. In Central Africa tool-making early humans roamed the plains 2.5 million years ago but there is no evidence of people here on the tip of South America until twelve thousand years ago.

Studying the street maps in the guide it was easy to forgetwhich town I was looking at, each bright gridiron named after the standard set of generals. In Argentina they are San Martín, Roca, Belgrano; in Chile, O’Higgins, Prat, Montt. The orange-lit lines of dead heroes tilted and came to meet us.

I asked the taxi driver to find a mid-price hotel. He said, ‘No problem.’ The Punta Arenas, no vacancies. Further down the street, the Liporace sounded and looked like a skin complaint. The taxi driver pounded the locked door. Red light was making weak rents in the eastern sky, four mongrels besieged a cat in a small tree. A man appeared and talked to the driver, shaking his head. The driver came back, ‘The town is full. The hotel is full.’

When a hotel named after a skin disease has no empty beds, I can believe the town is full.

The pavements were broken, and sheets of water lay in the road. We did the rounds. Sleepy faces came to doors, tired bodies leaned on the jamb. They shook their heads and cut their hands horizontally across each other. At the Laguna, a stooped thin man with a ten-month-old haircut and a pensioner’s cardigan declaimed ‘No room’ as if there was surely a Second Coming and anyone with a stable should clean out the manger.

‘I know another place!’ the driver exclaimed.

The Colonial was pink low concrete. It had two doors; no one answered either. The driver said, ‘I am sorry, this never happened before. I’ll stop the meter.’ The street was nearly light.

‘If I find somewhere now, will they charge me for tonight?’

‘They charge eight to eight, if you book in at five to eight you pay for the night’s sleep you just missed.’

‘Take me to a café, the one we passed at the crossroads in the centre.’

The Monaco was at the intersection of two heavyweight generals, Roca and San Martín. It was glass-walled and brightly lit, open twenty-four hours. A third of the tableswere taken, many by couples winding up the evening, talkingquietly. I drank large milk coffees. ‘Nothing to eat, sir?’

I had been awake forty-eight hours and three time zones. So tired I no longer knew if I was hungry.

‘Nothing to eat.’

The dawn began to fix the street in place, like a photograph being developed. People drifted away, the rest were drunk, quietly and gently drunk. A tired waiter broke a glass and smiled ruefully at the applause. Everyone took turns at looking at me, the only sober customer, the only non-smoker, the only person alone. Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid once held up the bank here. When the shops opened, I would buy a Colt 45 and free up some hotel beds.

Sometime after six I walked to the estuary, past the building designated an historic monument to record the visit of the first president to come to Rio Gallegos: Julio Roca. He spoke from a balcony and urged immigrants to populate the south and exploit the wealth of the MagellanStraits. The historic monument is a wooden balcony hangingcock-eyed from a big shed. I am sorry, but it is. The shore was a concrete esplanade, grey and perspectiveless as childhood. A red balustrade. The sea wall dropped ten feet to shingle, which shelved to sharp-smelling mud that glued down flimsy supermarket bags. Pigeons and gulls pecked a path across the mud. The water of the mile-wide estuary lay polished, ceramic. I was looking north; low flat-topped hills on the farther shore hinted at the majestic monotony of the plains which went north, horizon after horizon. This was the last country man found, this strand, this hill, the sky shining like wet paint; the dust already sticking to the fresh wax on my boots was made from flecks of legend. This was Patagonia.

Patagonia! The origin of the word, still a byword for being off the beaten track, has been much argued over. The Oxford English Dictionary, which has time to ruminate onthese things, is content that there is a Spanish word patagonmeaning a large clumsy foot, and that it derives from large clumsy shoes worn by natives. Spanish regional dialects still use patacones for big-pawed dogs, and the depth of the footprints the dancing natives made in the sand was remarked on by the first visitor, Magellan.

A second theory involves the Incas, who explored theAndes a long way south of the territory they formallyconquered. Their empire was not ancient. In 1532, when Pizarro rode his horse through its golden halls, the realmwas little more than a hundred years old. In the Incanlanguage, Quechua, the south was called Patac-Hunia, or mountain regions, and as Spanish does not pronounce ‘h’ the sound is very close to Patagonia. But why would men from an empire of the high Andes describe the lesser peaks of the south as mountain regions?

Bruce Chatwin was tipped off by Professor González Díaz that Tehuelche Indians wore dog-faced masks, andMagellan might have nicknamed them after a character in a novel called Primalon of Greece which features a dog-earedmonster called Patagon. It is an anonymous romancepublished in Spain in 1512 and translated into English by Anthony Mundy in 1596. As an aside, Mundy was a friend of Shakespeare, who would soon after have Trinculo say of Caliban, in The Tempest, ‘I shall laugh myself to death at this puppy-headed monster.’

Three flaws are apparent in the theory. Firstly, who names lands after novels? Secondly, it seems incredible that rough and ready adventurers would pause in theirjourneys on the edge of the unknown to make literaryallusions; and thirdly, there isn’t a shred of evidence that Magellan knew of the book.

But California is named after an island in a novel. Hernando Cortés sailed up the Gulf of California believing the land on his left was an island, not a peninsula, and named it after an island called California in the tale The Adventures of Esplandián, written by Garcí Ordóñez de Montalvo in 1510.

Secondly, as Bernal Díaz records, when his men walked a causeway into Mexico City in 1520, they ‘said that it seemed like one of those enchanted things which are told about in the book of Amadís’. The chivalric fantasy Amadís of Gaul was one of the real books which Cervantes slipped into the library of Don Quixote; literate soldiers carried them round in the same way that GIs carry comics.

Finally, Magellan could perhaps have known about Primalon of Greece. It was published seven years before Magellan sailed, and he spent a lot of time at court where such books were read by the chattering classes of the day. There are many odd theories about the origin of the name of the strange land of Patagonia; perhaps the oddest one is true.

In the dead of early morning the town was dreadful. Although a lot of money was made here in the livestock industries, it did not stay. The moneyed families built their belle époque mansions to the south, around Plaza Muñoz Gamero in Punta Arenas, importing everything from Europe, from the art to the architect. Here in Rio Gallegos, the post office and one restaurant excepted, there was no building in the whole centre worth a minute’s pause. All the tawdriness of a dead-end town with none of the excuses. Desperate for sleep, and groggy with lack of food, I bought cakes and savouries at a baker’s and walked past the pink Colonial Hotel once again. A young backpacker came out of it and climbed into a taxi. A bed.

The landlady asked me to wait ten minutes while she changed the sheets. When she had finished, I sat on the bed and took out a cheese and ham croissant. Under the cling film it had looked quite brave. Naked, the ingredients looked like naïve patriotic things which, in a rush of enthusiasm, had signed up as food but, on reflection, had realised their utter unsuitability for the task ahead. Tasted as seen.

The room was the size of a prison cell but without the amenities. No wardrobe no chest of drawers no table no toilet no basin no water no glass no carpet no rug no curtains no view. No matter, it had a bed, and a little gap down one side of it to get in and out. I walked to the bathroom in bare feet, looked inside, and went back for my boots.

What was I doing here?

Rainy Childhood Days

Voyages begin in books. Mine started with rainy childhood days and a house with one coal fire in the front room of our council house, near the Liverpool FC training ground. Wooden window frames with cold panes and tiny petals of orange mould in the corners. Knot resin weeping, pushing paint into blisters. A finger on the glass made two beads run together and zigzag down the glass collecting others, like chequers. My breath fogged the game.

We were three boys, I was in the middle. The first adult novel I read was Robinson Crusoe, when I was still small enough to curl up entirely inside the wooden arms of my mother’s tiny armchair. At that time the only sea I knew was the brown of the Mersey and the racing tides of the Wirral’s flat, estuarine resorts. I pored silently over the watercolour illustrations of palms and blue horizons, then took a red spade to dig my own fort in the back garden.

One damp Sunday I sat cross-legged in front of an oak utility furniture bookcase. ‘Da-aad,’ I drizzled, ‘what would I like to read?’ He tapped his faintly nicotined fingers on a green book spine, Percy Harrison Fawcett’s Exploration Fawcett.

‘Read this, he is a Harrison,’ he said.

‘Is he a relative?’

He looked out of the window at the rain, falling on the split paling fence. There was no prospect of going out. ‘Yes.’

I pulled out the book. In the front was a picture of a frowning man sporting a hip-length jacket and riding boots, and leaning on a wooden balcony. His propeller moustache waited for a batman to swing it into motion. The chapter titles called to me: The Lost Mines of Muribeca, Rubber Boom, River of Evil, Poisoned Hell, and The Veil of the Primaeval. I strode into the book and came out two days later.

Percy Fawcett made impossible journeys into the interior of the greatest South American jungles, again and again. He walked the frontiers of Bolivia to map them. Maps were crucial; without them the rubber barons would not know whose country they were robbing. He was in the interior most of the years from 1906 to 1913 and met travellers who had seen potions which made rock soften so it could be cut in the butter-smooth joints of the earthquake-proof Incan cities.

I swallowed tales of men who fell out of canoes in piranha-filledrivers, clung to the stern, and were removed at the river bank, skeletons from the waist down. They were killed by anacondas, poisonous spiders, flesh-rotting diseases and the cat o’ nine tails. They were sold to pay their own debts. Rubber magnates living on the world’s greatest flow of fresh water sent their laundry to Paris and constructed an opera house for Caruso, who came and anchored mid-river off Manaus. A cholera epidemic raged. Caruso walked the decks, and received the daily lists of the dead. Contracts beckoned, time ran out, he went home.Outside the opera house, the curved twin staircases leadingup to the classical mezzanine were cleared of cholera victimseach day. Dust motes descended shafts of light in the silent theatre.

The book was drafted in note form by Fawcett in 1923. There remained one dream, his search for the lost city of João da Silva Guimarões. In 1743 Guimarões had been hunting only for lost mines. A negro in his party had chased a white stag to the summit of a mountain pass. Below, on a plain, was a city of some sort. Next day they entered through three arches, so tall that no one could read the inscriptions above them. A broad street led them to a plaza. At each corner was a black obelisk. In the centre rose a colossal column of black stone on which was a statue of a man pointing to the north. The entire city was deserted except for a cloud of huge bats. Nearby they found silver nails lying in the dirt of caverns, and gold dust in the streams.

By 1925 Fawcett, discouraged by his failure to find men of his own invulnerability to hardship and disease, went out aged 57 with his inexperienced son Jack, and Jack’s friend Raleigh Rimmel, on one last search for the lost city of Guimarões. Fawcett’s last letter to his wife in England read, ‘you need have no fear of failure’. They were never heard of again. His surviving son Brian put together the book from his father’s notes and published it in 1953.

On another, interminable, wet afternoon in the school holidays, I opened a black book of narrative poetry and read The Rime of the Ancient Mariner. The prologue begins: ‘How a ship having passed the Line was driven by storms to the cold Country towards the South Pole.’

‘Are there any others like that one?’ I asked my father,when the other poems in the collection bored me. Thirty-fiveyears on I know the answer.

In my teens I painted, again and again, the spars of the Mariner’s un-named ship against livid skies. We moved toFalmouth in Cornwall, where I watched Robin Knox-Johnsontack Suhaili into the harbour and complete the first single-handed non-stop round-the-world voyage. It had begun as a race; he won it by being the only survivor.

I left Falmouth Grammar School, and went up to Jesus College, Cambridge to read geography. On the walls of the medieval dining hall were portraits of former scholars. Beneath them, Mr West, the Head Porter with the cut of W. C. Fields in his flesh and clothes, lectured us on the evilsof fornication and drugs. He did not seem heavily scarred by either. Thomas Malthus, author of the essay on population,looked over our heads. Coleridge, opiumaddict, stared down with great baleful eyes. He had writtenhome, ‘There is no such thing as discipline at our College.’That winter I discovered a reprint of Gustav Doré’s fabulousengravings for the Ancient Mariner. In 1978 I read Chatwin’s In Patagonia and, looking at atlases, my eyes began to fall south.

In Hay-on-Wye I was trawling the second-hand bookshops for material on Chile, when I found a hank of pages without a cover, which had fallen down the back of the other books. I pulled it out: An Historical Relation of the Kingdom of Chile by Alonso de Ovalle, a Jesuit. It had been torn from a larger volume. Although in English, the cover said it was printed in Rome in 1649. It was in such good condition I assumed it was a reproduction. The pages were fresh and white, they were flexible and clean. I bought it and took it round the corner to bookbinder Christine Turnbull. A gravel path led me down an avenue of lavender to her cottage workshop. She looked quietly over it and compared the paper with samples from her cabinets. She stroked her fingers down the spine. ‘The first English text was published in 1703. It should be full leather’

‘Then I'll have full leather!’

Alonso’s report is the first English account of Chile. It was dynamite in its day. The English translator confidedthat it ‘contains secrets of commerce and navigation, which I wonder how they were published’. Ovalle advised speculatorsthat a man with 40,000 crowns to invest, including inslaves, might earn a twenty-five per cent return ‘very lawful,and without any trouble to one’s conscience.’

I then found Lucas Bridges’s book on growing up in Tierra del Fuego as the son of the first successful missionary, Thomas Bridges. After a few chapters I knew I would visit Ushuaia and the bare savage islands of the far south. My great-grandfather had sailed there before the mast on the great square-riggers. My grandfather Thomas Harrison, born in 1896, sailed the Horn in steam and diesel, plying the last of the ‘WCSA’ (West Coast of South America) trade out of Liverpool. I was the first generation not to sail the Horn or fight a war. Instead, I would go to the end of the world, beyond Patagonia, to Tierra del Fuego. I would do more, I would see the Horn and find lost tribes. The child in me could go even further and sail the waters of Coleridge’s albatross and enter the watercolours’ blue horizons and sit on Crusoe’s imaginary shore. I had imagined these places; they must exist. All I had to do was look for them.

Rio Gallegos

By lunchtime I had slept four hours and woken too excited to stay in bed. I went out to look at the town with fresh eyes. I would like to say it helped.

Rio Gallegos was named after the river it stood on, but no one knows where the river got its name. One of the earliest houses belonged to a Doctor Victor Fenton. It was made in the Falklands from a design in an English catalogue, and shipped here, perhaps as early as 1890. It was here before the town, which grew around it during the following fifteen years. It is a two-storey wooden dormer with a long sun lounge running across the whole front. In 1915 it passed into the Parisi family. Señor Parisi’s wife was Maria Catalina. She was born one cold snowy August morning in 1860, in her family’s toldo or skin tent. They were Tehuelche pampas Indians and lived by hunting with the bolas. She had five daughters and three sons who survived to adulthood. All her life she made a living by native traditional crafts, making guanaco capes, sewing the skins together using the veins of ostriches. Her favourite food was mare’s meat with ostrich.

The house is now a museum. The stove has not moved in sixty years; some furniture came from other early houses. The study had three old Remington typewriters. In the lounge a colossal Canadian Victrolla brought over in 1904 played a fine tango on a paste 78. In the kitchen was a washing-machine, hand-cranked and looking like a butter churn with wringers above it. But I was more taken with the story of Maria Catalina. Most of her children would still be alive. I talked to Señora McDonald, now retired, whose Scottish father had come to Patagonia and married a Spanish woman. She spoke English with a strange rural Scots edge to it.

‘Are any of Maria Catalina’s children still alive?’

She thought for a moment. ‘One of the sons, Roberto, lives a few streets away.’

‘Is he the kind of man who would mind me calling in for a chat?’

‘No, not normally, but his wife died of cancer two days ago.’

This was the dry season; it never rains here in December. But every few hours the rain lashed down like cold nails. People shook their heads and said ‘El Niño’. I walked round Rio Gallegos once more and decided to leave. My journey was planned to follow a V shape, moving south to Tierra del Fuego, as far as I could go down the east coast, then to turn north up the west coast. But first I had to backtrack north a short way, to Puerto San Julián. I wassure it would now be a dull town, but I wanted to see it, because it was the scene of treason, bloodshed andexecutions where tragedy was followed by farce. It was the launchpad for the first two circumnavigations of the world, by Magellan, then Drake. And, of course, Magellan and Drake both met and talked to giants so tall the sailors could not touch the tops of their heads.

Puerto San Julián

Thebusmakingthefive-hourtriptoPuertoSanJuliánleftathalfthreeintheafternoon.ThistimeIrangaheadtobook;therewerenomedium-pricehotels.Ithoughtaboutgoingtothebathroominmyboots,andbookedtheoneup-markethotel,theBahíaSanJulián.

At the travel agents I got on the bus. Everyone else was being picked up from home. Many had been Christmas shopping in Rio Gallegos, and waded on board festoonedwith bags and boxes. Every seat was filled. When weeventually left town an hour later, the only place left to put my legs was in the aisle. We pulled in at the airport. The driver collected eight large plastic packing boxes and filled the aisle.

The landscape was the colour of burnt grass, stony, empty and huge. The road appeared flat, but was not. After a while the eye learned to see the slight turns, the subtle rises and falls. There were hidden dips betrayed by the road shimmering as a grey soft-edged lens in the air above them. One of the few towns we passed through was named after an early administrator, his whole name: Comandante Luis Pedra Buena! A mid-stream island was wantonly green with trees and flower meadows. Then we entered the great basin where the land falls to one hundred metres below sea level, the lowest in all Argentina. The sun dropped, the dry grass colour turned corn gold and then red gold.

At ten-thirty we rolled into the unmade streets of Puerto San Julián, veering all over the road looking for purchase in the mud. The driver began dropping people off, picking out places where they would not drown walking to the kerb.Eleven o’clock came. He pulled out onto a well-lit dualcarriageway, and pointed at me. There stood my brand new hotel. I walked self-consciously onto the thick blue carpets, staring after me to see how much mud I was trailing. A large bar supported two drinkers watching football on the television. The smart receptionist showed me to my room. It looked as though I was the first person ever to stay in it.

‘How long have you been open?’

‘Not long, two years.’

Early photographs of the town, lining the hotel corridors,had a strange bare quality to them, like a town in a child’s dream: big simple buildings, one car, one house, one dog. A single steamer stood at a short pier. Thousands of sheep trotted across an empty square and through a wooden V onto a gangplank and into the hold. One man, stationary on a horse, watched over them. Clutter, the detail that makes life real, had not arrived.

Morning was overcast. I walked down the road at the side of the hotel to see the south end of the bay. Above the high-tide mark was a zone of grassy flats criss-crossed by channels. The bay’s circle was wide; low hills came down to grey sandy cliffs. The water was milky blue from fine sediment. As I descended the hill I left the gridiron, the invader’s geometry, and entered a barrio of makeshift houses that followed the streams and contours, responding to the land. Each rested at the size it had reached when money ran out. Tiny birds followed me through the scrub, keeping level or just behind. They were rufous-backed negritos, the females dun, the males a shimmer of red-brown and shining blue-black. Perhaps they follow people because we disturb insects for them to feed on, but nobody really knows.

Mongrels, long-haired golden mongrels, squealed and twisted on thin rope tethers, their anguished yelps squeezed from far back in the throat. The plaint of the dogs’ barking was blown out to sea by a flat wind. On the wall round the bone-dust sports field lone graffti appealed: ‘Don’t fail me.’

I was walking in the steps of Magellan and Drake, I would also be following in the footsteps of a more recent buccaneer, the English bandit El Jimmy.

El Jimmy

The writer Herbert Childs came here by boat in the 1930s for his honeymoon. He was searching for an English-born gaucho and bandit who wanted his story written – James Radburne, nicknamed ‘El Jimmy’.

Wondering if all the tales of rough frontier life were true, particularly the casual cut-throat violence of the gauchos, Mr and Mrs Childs reached Puerto San Julián, and went ashore to stretch their legs. They found it dull rather than dangerous. Coming back to the ships, they shared the ferrywith three gauchos in full rodeo dress. Once on board, a policeman steered them towards third class. Anotherpassenger came up alongside Childs, ‘They’re going to Rio Gallegos for trial.’

‘What did they do?’

‘They were in a gang. A fourth one took a bribe and betrayedthem to the police. They caught him, skinned him alive, and cut all the skin off his face to make him hard to recognise.’

‘Why aren’t they handcuffed?’

‘They’re no danger to anyone else. They only killed because a friend betrayed them. That’s not murder downhere, they’ll get seven years, at most. There’s no point tryingto escape and giving the police a chance to shoot you and get a reward – not over a little point of etiquette.’

In England, when James was seventeen his father died leaving twelve children. James did not help his mother’s desperate plight. Instead he turned to poaching and had an affair. Gossip led to discovery. The girl’s furious mother went to court. The judge was swift to reach a verdict, plainly embarrassed by the mother’s principal tactic of flourishing the girl’s knickers to the courtroom. Time to go. A nearby farmer had shares in a farm in Patagonia. Jimmy did not know where Patagonia was, but he went. After a swift passage of twenty-eight days, he stepped ashore in Punta Arenas on 8 December 1892. He was asked the question all fresh young men from Britain were asked: ‘Was it poaching or a girl?’

‘Both.’

Jimmy already had the right credentials for Patagonia, and he loved the outdoors and the horses, the hunting and camp life. But in a land of murders and thieves, a mere poacher needed to make a name. He made himself the best gaucho, shepherd, jockey and horse trainer in the district, and one of the best in the region. To his father’s fist-craft he added a knife and a gun, and his reputation became an invitation for every hardcase in Patagonia to take a pop at him.

One day, when shearing finished at the Denmark Estancia, he was kept on for a few weeks to cut fence posts and rails in the woods. He saw something which made him tingle, the toldos, or guanaco skin tents of Tehuelche Indians. Che means ‘people’ and tehuel means ‘of theSouth’. He was to befriend them and live with them, learningtheir skill and craft, their soft ways of taming horses. They had no bows or arrows, and hunted with the apparently primitive bolas. But in the tall grass of the pampa, the bolas will reach an animal when a lasso will be smothered by the grass, and an arrow deflected.

Two round stones were sheathed in leather, then bound six feet apart with rawhide. A third, egg-shaped stone wastied by a line to the centre of the first line. The throwcomprised a combination of horizontal and vertical swings to make them fly in a Y shape and wrap the balls round the neck or legs of a horse, guanaco, cow or ostrich. For ostrich and farmed animals, packed gravel would be used instead of stones, so as not to smash the legs. Charles Darwin was given a brief lesson, swung the stones energetically round, and fell poleaxed as they hit him on the back of the head.

Jimmy, practical countryman though he was, could never make a bolas whose balance he liked as much as the Tehuelche-made ones. Whenever there was a serious hunt, he traded other goods for an Indian-made one.

The Tehuelche were so famous for their horsemanship that when the St Louis World Fair was held in 1904, theArgentine government wanted to send six of them tocompete in the rodeo events. Baller, the local commissioner, was not liked. He gave his son the job of taking the party to St Louis. They didn’t like him any better. Young Ballerwas reduced to picking four men from a group whichhappened to be camped on his doorstep. Coloko was good at balling ostrich; another, Loco, was a good jockey. Casimiro and another old man were regarded as pretty well useless at most things. The Indians who remained saidBaller had picked the most useless men, and then the ugliestwomen to go with them. But when they returned they brought home the prizes for lassooing and riding, beating all the American cowboys and the South American gauchos.

Not all Tehuelche pastimes were so constructive. Oneway of killing the time was to catch a viscacha, a cuteanimal halfway between a rabbit and a squirrel, and skin it alive without killing it. Then they would let it loose in a thicket of thorns and bet on how long it would survive. They could not understand the settlers insisting that they stop this harmless fun. The viscacha has its own strange hobby – collecting hard objects of all kinds to adorn the entrance of its burrow. Darwin heard how one man, riding home at night, realised he had lost his watch. He went backin the morning and, by searching the entrance of everyviscacha burrow along his route, soon found it.

After a day at the races Jimmy was caught with a dud cheque and was imprisoned. He promptly escaped but stayinganonymous was hard. If ever he got into a dispute, it only needed someone to find out he was called James. There was no other James in the district. He was El Jimmy, the bandit, the jailbird, and the other man had a mark onhim. He went native and lived with Chief Mulato in thetoldos and fell in love with his daughter Juana. Her father, in a rare drinking session, promised her to the winning owner of a horse race Jimmy had set up. The jockey on Jimmy’s horse was Montenegro, a man he had quarrelled with and did not trust, but a natural horseman. Montenegro threw the race in return for marrying Juana. The chief would not go back on his word, drunk or not. Jimmy’s enemy Montenegro rode out with his girl.

Jimmy then lived with another Tehuelche woman. She became pregnant. Thirty years later he recalled to Herbert Childs the night of the delivery of his first child.

When the time come, I went outside after getting some other chinas (women) to help, telling them to call me if anything was needed, and to call anyway when the baby was born. I’d been outside quite a time and there was no call, though everything got quiet in the toldo. I went and asked if everything was all right and they said for me to come in.

I went in. The china was all right. I asked to see the babe and they showed it to me, pretty as anything, with blue eyes and white skin. It looked like a proper English baby. I was pleased to see it, but the more I looked, the more it seemed something was wrong. It was so still. I touched it and it was already cold. They hadn’t let it live, though it was born all right.

They didn’t ever think it was right for a child not looking like one of them to grow up with them.

Jimmy also remembered a winter of such cold that men and animals perished: starved and stranded by the snow. It was 1904 and he was visiting the toldos. When after four days and nights the storm let up, there was seven feet of snow, and it stayed. A skunk came into the tent. They killed and ate it, and two more before the thaw came. ‘They tasted like good chicken. I’d rather eat skunk than lots of animals, like pumas; they’re awful.’ By late spring most of the horses had died of starvation. They had first eaten each other’s tails and manes. ‘When I found them first the skin was almost rattling on their bones. I thought it a pity they couldn’t eat meat becausethere was dead sheep everywhere, and men waswool-gathering, plucking wool off dead sheep. This wool does not bring as high a price as clipped wool, but if well plucked, and if it has long staples, it helps a bit if your sheep get all killed.’

They travelled, in part to garner news, but also to feel the space of the pampa again after their confinement. The Megan Estancia of fourteen thousand sheep had one hundred and seventy-five alive. There were circular rings of dead horses where they had walked round and round trying to keep the ground clear, until one fell and stopped the clock for ever. There were some new and grim harvests. Jimmy took four hundred skins from frozen guanacos.

In later life he met Juana again. She had had enough of Montenegro and left him. She and Jimmy ran north and built a farm and a family. It had been a long road, but they were happy. Even here the English owners of much larger neighbouring farms tried to squeeze him out by bribing officials. Jimmy fought them, and won. They lived out their days there.

Old Chief Mulato was not so lucky. Local officials tried to cheat him out of his land and resell it to white farmers. He was now a relic of another way of life, but he still had the deeds to his ancestral land. In 1905 he left for Santiago to fight for his land and prove his ownership. Most of his family went with him. On the way home Mulato’s niece died of illness unexpectedly. His son came to fetch Jimmy. Soon after Jimmy arrived at the camp, Mulato’s wife died. Mulato himself died at midnight, the son a few days later. In Santiago they had picked up another of the white man’s diseases, smallpox. Farmers took the land.

Rory Wilson

When I woke up on my first morning in Puerto San Julián, sun filled the streets. In the bright dining-room, two tables away, a tall blond man with a deep narrow chest spoke German to a woman with strong handsome features and long black hair.

I had to find a boatman called Carlos Cendron to take me out to the island where Magellan and Drake held legal trials and executed noble companions amid the burrows of Magellanic penguins. Near the beach I found a corrugated iron house freshly painted in warm pink, and a localwoman leaning over a low picket fence, talking to the couplefrom the hotel.

‘I am looking for Carlos.’

The blond man listened. ‘Are you English?’

‘Yes.’

He put his hand out. ‘Rory Wilson.’

I said, ‘You’re staying at the Bahía.’

‘There was someone new at breakfast! I never notice because I am always talking! This is Mandy who has to put up with me.’

‘But you were speaking German to each other – I am sorry – travelling alone makes me eavesdrop.’ The English are no sooner introduced than they start apologising to each other.

‘Mandy’s German, we are both at the University of Kiel, we are doing penguin research all down the Argentinian coast. So what do you want Pinocho for?’

‘Pinocho?’

‘Everyone calls Carlos Pinocho.’

Out of the house came a man with a light fast frame and a lot of muscle. He ran his fingers through tight curly hair and put out his hand.

Rory added, ‘It means Pinocchio.’

I said, ‘Hello Carlos.’

‘We’re going to spend a day measuring penguins and packing up our research site on one of the islands,’ Rory said. ‘Come with us if you want. On the way back Pinocho will take you to Execution Island – here they call it Isla de la Justicia.’

Carlos hitched an inflatable to the back of a 1962 American Ford pick-up. Rory and Mandy pulled me up into the truck. Ten minutes later the inflatable was in the water, Carlos gunned the outboard, the bow beneath me kicked, and we planed over the glass of the harbour. The bay was enclosed by low islands and shingle banks. More estuary than Atlantic. Dimples appeared to our left. ‘Commerson’s dolphins,’ said Rory, ‘very rare. Very difficult to see them anywhere else. They’re odontoceti, toothed dolphins, cousins to killer whales. Next to nothing known about them.’

One came round under the bow and blew out water in my face.

‘Lovely animal, five or six feet long, a lot of white, each pattern unique, very sociable here.’

Commerson’s dolphins were discovered by the naturalist Philibert de Commerson who sailed with Bougainville on the first French circumnavigation of the world of 1766–9. He took his valet Baré along. When they got to Tahiti the natives noticed what his colleagues had not. Baré was a woman, Commerson’s mistress.

The dolphin under the bow swam with its back against the rubber. I left the camera in the bag, and the mini-disc recorder with it. I reached out and touched the back of a wild dolphin. Soft and smooth to the touch, neither fish nor flesh. It blew over my face again. Sun on my neck. Bliss.

The tide was ebbing. We came to shallows at the north end of the bay where the water drained, just inches deep, over narrows between island and shore. Carlos lifted the outboard and punted. We came over into deeper water and pulled up under a stilt house at the top of the beach.

‘Is this your house?’

‘My island.’

‘Do you live here during the summer?’

‘I come here a lot, three or four days a week if the weather’s good. I fish, fix a few things.’

‘Who else lives on the island?’

‘One hundred and thirty thousand Magellanic penguins.’

They lay on their backs like otters, rolling, frisking, cleaning. They swam slowly to shore and walked up the beach in lines. They stood around in groups of two or three dozen. We beached among samphire, and landed the gear.

The island is low, mostly thirty or forty feet high, and covered in scrub bushes. Penguins come here to burrow and nest, and every footstep I took was within arm’s length of a nest burrow. Their territorial call to intruders is like a donkey’s bray. Their personal call to identify chicks and partners is a bray with vibrato.

In the hut Rory sorted equipment: stomach pump, bowl, scales. ‘They are remarkable birds, nesting everywhere from Cape Horn to near Chiloé, way north up the Chilean coast.’

‘I know, I thought I was seeing things.’

‘There’s a penguin colony even further north nesting on the Atacama coast – the world’s driest desert.’

‘How long have you been researching these penguins?’

‘Penguins? Twelve years.’

‘What will this experiment tell you?’

‘It’s one of a chain down the Argentine coast. The seas along the east side of South America are less rich than the west. All along the Chilean coast the cool nutrient-rich Humboldt Current brings a conveyor of food up from the Antarctic. The coastal shelf round here is not yet badly overfished but it will be. We need to know what they eat and what they need, and where they go for it.

‘We spend three weeks running north up the long coast from Cabo Virgenes, at the east entrance to the Magellan Strait, to Peninsula Valdes, where they film the whales.’

He clipped a harness round his waist, and picked up a board like a plasterer’s hawk, with a curve cut into one side. Mandy carried a blue plastic bowl, and an orange rubber tube with a bulb pump in it. Carlos studied a clipboard.

Rory outlined the work. ‘We’ve got six penguins out there, each with a thousand pounds’ worth of tracking equipment on its back. It’s our last day here, I’m hoping to get them all back.’ From a bag he took a deep green resin block the size and shape of mackerel head. ‘We tape these to the back of the bird; they record the depth, speed and direction of the birds. We download it into a computer and plot where they’ve been. We pump their stomachs and we know what they’ve caught, and there’s our picture of their feeding needs. My own invention,’ he said proudly, and held up the wooden board.

‘How are the chicks doing this year?’

He frowned. ‘Despite the numbers this isn’t the ideal place for them. Their preferred food is fish; further north they get anchovy, here it’s sardine, but it’s not plentiful,so they have to take a lot of squid, which offers poorer nutritionand takes longer to digest. If the squid is not fed to the chick beak to beak, it will not even recognise it as food, and will let it lie on the floor of the nest. In this part of Patagonia it shouldn’t rain at all in December. But this year there was heavy rain. Water ran down the burrows and into the nests. The chicks’ down is absorbent, they got wet, so they got cold and weakened. Some of the first chicks died, and most of the second chicks, which hatch two days later and are often weaker.’

He straightened his back and scanned the beach. ‘I think there’s one of ours now.’ The bird making its way across the honeycomb of paths seemed to know it was being looked at, cocked an eye over its shoulder, and ran off, doing a presentable Charlie Chaplin. Rory disappeared over a low ridge. There was a loud braying noise. He came back carrying a penguin.

He knelt on the ground with the bird upright between his thighs, clipped lines from his harness around each leg and held the back of its head. ‘Never hold the flippers or feet; they go berserk, and those beaks are like wire cutters. Imagine putting a Stanley knife on your finger and then putting a seven pound weight on the knife – that’s what they do to you. Most researchers use gauntlets. It’s just not necessary if you know how to handle them. Of course no system is perfect.’ He held out a finger with a deep cut scored along one side. ‘That’s three weeks old, my own fault. Ever seen inside a penguin’s beak?’

I thought carefully. ‘No.’

He prised it open with great difficulty. The inside wasbrilliant pink and the roof of the mouth and the tongue were covered in large strong bristles pointing downwards. ‘They eat all their fish head first; these act against the scales, like Velcro. Last sight many fish see.’

Mandy passed him an orange tube like the ones onschool Bunsen burners. He slid it down into the bird’s gullet.

‘How much does it distress the bird?’

‘They puke a lot, naturally. They regurgitate for chicks, and a lot of seabirds actually throw up food when attacked, to distract predators. For them it’s not a big deal. For us it would be horrible.’ Mandy pumped water down the tube, filling the stomach until water spilled from the beak. He whisked it upside down and spilled about a third of its catch into the bowl. The bird kept the rest. ‘Besides it’s a lot less stressful than the previous technique.’

‘What was that?’

‘They hit them on the head and cut the stomach open.’

Rory set the bird down and released his grip. It shot away ten yards, drew itself up straight, and walked away with the rest of its catch to its waiting chick.

We poked about in the bowl and began to lay out fish-heads and squid in lines. ‘See what I mean about the squid? These fish have been in the gut the same length of time, and are half digested.’

I picked up the squid. ‘This is so fresh you could wash it and sell it.’

‘And that’s what it’s like for the chick: best part of a day longer to digest it, and poorer nutrition when it does.’ He pulled out a small green beak. ‘Squid beak, stay around in the stomach for months, can’t count these.’

A beautiful hawk came over. Excited, I pointed it out to Rory. ‘What is it?’

He glanced. ‘Don’t know, if it doesn’t go underwater and eat fish I’m not really interested. Can’t help it. Hold this bird a moment.’ He gave me an adult. I took the back of itshead and pulled it between my legs. It was a ball of muscle, like holding a Staffordshire bull terrier. It stayed perfectlystill.

‘You’ve got the hands,’ he said. I eyed the beak.

I left them, and went to photograph birds on the beach.There were black and Magellanic oystercatchers; it is unusualfor them to be in the same territory. The black ones had ascarlet bill, and orange-red eyelids, and the iris was astartlingorange-yellow. Dominican gulls were nesting, and skuasharried the adults, trying to get at the chicks and eggs. I lay down in the pebbles and waited for them all to get used to me. I was too busy looking inland at the oystercatchers to notice what was creeping up behind me. But when I rolled to face the sea, a group of two dozen penguins had left the water’s edge to come and stare at me. After a while, onewould lean forward and, after suffering a minute of unbearableindecision, be overcome with curiosity and take another couple of steps nearer. The others would follow, then stop,until the leader began to tremble and, unable to controlhimself, patter closer. In the end, I bawled out laughing, and they scuttled back to the water’s edge.

The wind sprang up and we went in the house to drink scalding maté. Rory scanned the bay. ‘There’s still a one thousand-pound penguin swimming around out there.’

Carlos said, ‘I’ll be out here fishing, I know which nest it belongs to, I’ll call by.’

We loaded the boat. I looked back at a seventh of a millionpenguins. ‘What’s the island called?’ I asked Rory.

‘We just call it the island. I don’t know if it has a local name.’

Carlos nodded. ‘It’s called Cormorant Island.’

I turned for a last look. A hare sat on the grassed beach top. A hawk stooped.

The inflatable took us across the bay. The evening was growing cold, but before we went back to the mainland I had to visit the place of execution which had brought me to Puerto San Julián, Isla de la Justicia, the Island of Justice.

The low bank lay further offshore than CormorantIsland. The highest point sustained just enough soil to nourish a few thin bushes. The rest was shingle, but itbustled with life: gulls and blue-eyed cormorants were crammed into nesting sites. Our boat bumped gently against the beach and Carlos killed the engine. Wavelets scrabbled in the pebbles, the wind lifted the dove-grey feathers of the most beautiful of all gulls, the dolphin gull. On deep vermilion legs it walked up the beach, looking over its shoulder at us. It picked its way onto grass whose roots curled around the bones of noblemen.

I thought about how this remote shingle islet had dogged Drake on his return when he was attacked by the friends and family of the well-connected man he tried here. It has been called not only the Island of Justice but also the Island of Blood. There was certainly blood, but was it spilled injustice or revenge? When he came to his decision to convict,and condemn, Thomas Doughty, Drake must have beenobsessed by the only other commander who had ever troddenthis land: Ferdinand Magellan.

Island of Blood

Here at Puerto San Julián, on this little island in the bay,nearly five hundred years ago, he and one of his captains,Sebastian del Cano, came head to head, and Magellan showed what he was made of. When his flotilla arrived on the last day of March 1520 to rest his men and repairthe boats, he had come too far to compromise his ambition.The shingle banks may have shifted about in the halfmillennium which now intervenes, but the overall scene would have been much the same. The low islands would have killed the power of the waves but offered no shelter from the cutting winds.

He had already sailed off real maps, in among the seamonsters which breached and spumed around their margins.The preparation had been long and meticulous. There would be no adventure like it until Yuri Gagarin went into space, but with Gagarin we knew what was awaiting. For Magellan, the leaving of this meagre harbour was a launch into a totally unknown cosmos.

Magellan had read in Aristotle that the southern hemisphere was a place where no men lived, but he found teeming villages. This was the end of Aristotle. In fact Magellan didn’t find just men; he found giants, and so did subsequent explorers, right up to the eighteenth century. With Magellan was Antonio Pigafetta, a young nobleman from Vicenza accompanying the Papal ambassador to theexpedition. He was an inquisitive man and a talented linguist.

But one day (without anyone expecting it) we saw a giant who was on the shore, quite naked, and who danced, leaped, and sang, and while he sang he threw sand and dust on his head. Our captain sent one of our men toward him, charging him to leap and sing like the other in order to reassure him and show him friendship. Which he did. And when he was before us, he began to marvel and to be afraid, and he raised one finger upward, believing that we came from heaven. And he was so tall that the tallest of us only came up to his waist.

However, any trouble the giants gave Magellan was nothing compared to what he brought with him. Within two days of arriving at Puerto San Julián there was mutiny. There were men in Magellan’s fleet who outranked him socially and plotted against him, perhaps before the expedition had even sailed. On the morning of 2 April Magellan found three of his five boats were now in the control of four rebel officers, Juan Cartagena, Sebastián del Cano, Gaspar Quesada and Luis de Mendoza. Magellan rightly guessed Mendoza was the ringleader. He sent one boat with a messenger to row in full view towards Mendoza’s ship, while a second boat came round behind and boarded it by stealth. Mendoza was stabbed to death, and the crew surrendered. A strong tide pulled another rebel ship from its anchors and underMagellan’s cannon. It was bombarded, boarded and subdued. Cartagena and del Cano gave up.

Trials were held. To encourage contrition, Magellan firsthad the body of Mendoza disembowelled, cut in pieces andhung on a gibbet. Quesada was beheaded, disembowelled, quartered and hung next to him. Cartagena had been directly appointed by the King, so Magellan put himashore, with a troublesome priest, giving them a small sackof biscuit and their swords. André Thevet’s 1584 biographyof Magellan noted: ‘By these means, he softened the others considerably.’

Sebastian del Cano and dozens of others found guilty were forgiven. Magellan simply had too few men to execute all the guilty. By a macabre irony, the next visitor to this harbour on the world’s rim would enact another grim piece, a shadow theatre of Magellan’s own drama.

‘With Death or Other Ways’

Magellan’s successor in southern exploration was Francis Drake. When, in 1577, he boarded the Pelican to begin his circumnavigation, he was thirty-five years old, clear-headed, fiercely loyal to his family, and ambitious. In authority he was ruthless, and had a knack of using his temper to advantage.He was not cruel or reckless; in anger he never forgot what he wanted. When war broke out with Spain, Queen Elizabeth secretly took shares in Drake’s proposed raid to enter the South Sea through the Straits of Magellan and plunder Spain’s Pacific wealth. She made it very clear that Lord Burghley, who had undermined similar previous proposals, must not know.

On board the Pelican was Thomas Doughty, one of a group of gentlemen soldiers, a scholar and linguist, welleducated and well connected. He had used his influence to help the expedition gain favour, a point he liked to remark upon. In the beginning he had command of the landsoldiers. Drake was Admiral and overall commander, but he was not, in the eyes of a career courtier like Doughty, a gentleman. It became clear that neither officer nor gentleman could quite bring themselves to defer to the other.

There are a number of accounts of the voyage; each one takes sides and makes errors, but it seems certain that Doughty was soon acknowledged as leader of the group of gentlemen, well connected, young, and with too little to do. In the Mary, Thomas Drake and Thomas Doughty accused each other of pilfering. Francis Drake went on board and listened to two unsatisfactory stories. Toplacate Doughty he formally made him captain of thegentlemen soldiers on the Pelican.

Doughty thought the new job demanded a speech. He called the crew together.

My masters, I have somewhat to say unto you. The General hath his authority from her highness the Queen’s majesty and her council such as hath not been committed almost to any subject afore this time: to punish at his discretion with death or other ways offenders; so he hath committed the same authority to me in his absence to execute upon those which are malefactors.

This warrant would soon be invoked to secure a man’s destruction. But not by Mr Doughty.

Doughty’s ship lost contact with the rest of the fleet, Drake suspected deliberately, and bad weather closed in. Drake had had enough; he roamed the deck swearingThomas Doughty had conjured up the bad weather bysorcery. Magellan’s problems had been real-life drama. Drake’s now became tragic and even, sometimes, comic theatre. Doughty swore at Drake and was tied to the Pelican’s mast for two days. Released, he refused to go to another ship until Drake prepared a block and tackle, and threatened to unload him as cargo.

On the last day of June Drake sailed into the bay of Puerto San Julián to prepare boats and crew for the passage into the Pacific, as Magellan had fifty-eight years before. They met giants for a second time. Further north Francis Fletcher had said of them, they ‘showed us more kindness than many Christians would have done, nay more than I have for my own part found among many of my brethren of the ministry in the church of God.’ Drake gave the giants food and drink. Only once before had the giants seen men like these. Once out of bow-range, one Indian called out in rusty Portuguese, ‘Magellanes, Esta he minha terra’ – ‘Magellan, this is my country.’ A vain and ironically prophetic cry.

They found Magellan’s gibbet, a spruce mast, fallen over. The cooper took a piece from it back to camp and from it made souvenir tankards to sell to his shipmates. Digging in the shingle and sparse soil, they found the bones of Luis de Mendoza, Antonio de Coca and Gaspar Quesada. Drake knew the resolute man who put them there was the only one whose expedition had succeeded in passing through the Strait and reaching home. In the twenty years between Magellan’s success and Drake’s birth, twenty-one ships had tried to follow his course: twelve were wrecked on or near the Strait, and the rest foundered elsewhere, or retreated the way they had come. With those odds stacked against success, there was only one response to dissent.

There are two contemporary accounts of the trial of Thomas Doughty at San Julián. One was written by Drake’s chaplain, Francis Fletcher, who was courteous to Doughty, but his sympathy and loyalties were with Drake. The other, by John Cooke, was hostile. His ship turned for home early, so, writing his version at a time when he thought Drake would not return, he pulled no punches. Looking back, he damned Puerto San Julián as a place where ‘will was law and reason put in exile’.

A chair was taken out to Isla de la Justicia and all the crews commanded to attend. In the path of Drake’s mighty ambition was Thomas Doughty and his supporters. A gameof cat and mouse began. Eventually Doughty made a mortalblunder: name-dropping, he let slip that Lord Burghley knew of the voyage.

‘No,’ said Drake, ‘that he hath not.’

‘Indeed he hath.’

‘How?’

‘He had it from me.’

‘Lo, my masters, what hath this fellow done, for her Majesty gave me special commandment that of all men my Lord Treasurer should not know it, but to see his own mouth hath betrayed him.’

The jury found him guilty, and a game of manners followed.Drake asked Doughty, ‘Would you take to be executed in this land, or to be set on the main, or return to England, there to answer this deed before the Lords of her Majesty’s Council?’

Doughty thanked him for his clemency and asked to answer in the morning. Drake agreed.

Next dawn Doughty dismissed the option of being marooned ‘among Infidels’. He also thought no man wouldaccompany him home to England, so he asked to be executed. Drake offered him shooting, which he would do himself, so Doughty would die at the hands of a gentleman. He chose beheading.

The next day Chaplain Fletcher celebrated communion, then Drake and Doughty dined together. No account suggestsit was not convivial. Doughty said he was ready for theexecution but asked that he might ‘speak alone with him some words’. They walked alone along the shingle shore some seven or eight minutes; what they talked about no one knows. When they returned Doughty remarked ‘he that cuts off my head shall have little honesty, as my neck is so short’. He laid his head on the block. The axe fell. Drake had needed an argument he would win; his text was Thomas Doughty’s head. Drake held it aloft: ‘Lo, this is the end of traitors.’

Digging a grave they found a grindstone broken in two, and set one part at the head and the other at the foot.

Absent Millionaires

In the taxi office at Puerto San Julián I explained that I wanted to go north along the coast, then find Estancia Coronel, the site of a failed early colonial settlement. We negotiated, and I showed a map to the driver – unshaven, five feet nothing, blackout sunglasses and a pack of Marlboro.

The boss came out, Marcello, thirty-ish with clear skin, a thin student beard, and hair brushed back, thinning withoutretreating from the forehead. We agreed a price. I held out a hand, ‘I’m John.’ He kept his hand in his pocket. The driver asked, from behind his shield of night, ‘So where are we going?’

An enormous explanation followed.

The driver nodded. ‘So I am going to take....’ I lost track of his Spanish.

‘No.’ Marcello borrowed my map. ‘You’re going...’ Another detailed itinerary was launched.

‘Understand?’

‘Yes. I am going to go up to the top, straight on at the end of the main street...’

‘No.’ Marcello went into the back of the offices. The driver took me to the car, I threw my bag in the back seat. He said ‘No’. Perhaps No was the company motto. He asked me to sit in the front. Marcello appeared with Maxi, his six-year-old son. The driver smiled at me, ‘They are coming to show me the way.’ He was genuinely pleased. At the end of the main street we turned right onto a dirt road and climbed through gentle hills of grasses and low bushes.