Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

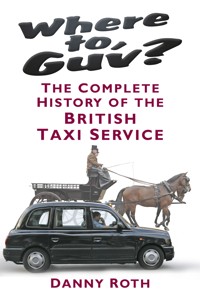

Whether living in an urban sprawl, a sunny suburb or rolling countryside, the taxi is a mode of transport that no doubt every resident of the UK will use in their lives. So prevalent is it in British society that the black cab has become one of the most iconic symbols of the country and its capital. Here Danny Roth presents the most comprehensive history of the taxi service of Britain complete with in-depth appendices and a wide-ranging, fascinating collection of 250 taxi images. Beginning from the birth of the taxi, four millennia before Christ, through Victorian times to the present day with views on the future, no stone is left unturned in this history of British taxi service. Accessibly written and filled with technical detail, this is a volume no car or taxi enthusiast can do without.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 411

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

To the memory ofLawrence Anthony Grant7 January 1944 – 28 June 2005

Contents

Title

Foreword

Introduction

1 Early Days: Up to 1834

2 The Victorian Era: 1834–97

3 The Turn of the Century: 1897–1918

4 Two World Wars: 1918–1945

5 The Post-War Period: 1945–61

6 Competition Arrives: 1961–Present

Appendices

Plates

Copyright

Foreword

‘The blind leading the blind’ – this taxi history is written by someone who has never driven a taxi and never will. The driving force was my father-in-law, Lawrence Grant, a well-known taxi-trade personality, who died suddenly on 28 June 2005.

I therefore start with a short biographical tribute to a lovely man. Lawrence Anthony Zeidman was born in Ware, Hertfordshire, to London East-End evacuees; they returned early in 1946.

Health-wise, he started with acute myopia and a year’s near blindness in 1950–51, forcing attendance at a school for the partially sighted in, of all places, Hackney. In 1953, his parents – having added a daughter and second son – moved to Harold Hill, Essex. He thence attended a normal primary from 1953 to 1955 and, after failing the eleven-plus, a secondary modern, Quarles, Harold Hill until 1960. He achieved creditable athletic standards, notably as a half-miler, winning three gold medals at schools’ events but, more importantly, being successful in White City’s National Schools’ meeting, where his 2 minutes 2.7 seconds equalled the then women’s world record.

His father, Sydney, was a caterer specialising in wine purchasing; Lawrence participated from childhood, becoming an honorary member of the Wine Tasters’ Association, Sommelier’s, at 17. Following paternal footsteps, he entered South-West Essex Technical College’s catering section. Two years saw his passing with distinction. However, domestic problems escalated, relationships with his parents became strained and he joined the merchant navy.

Catering qualifications enabled him to serve as senior wine steward. His first trip was with the famous Royal Mail ‘A’ boat Amazon. Another Royal Mail cruise ship, the Andes welcomed him later for two and a half years. Then the New Zealand Shipping Company, Rangitoto, took him to their home country; he sailed with Corinthic to Australia.

In autumn 1964, he returned home to work at Queensway’s Finch’s Off Licence. This lasted until early 1967, when he married Jasmine Lawrence, later joining London Transport, anglicising his surname to Grant.

Poor eyesight precluded bus driving, but he was accepted as a Clapton Garage-based conductor. Over two years, matters improved noticeably and by 1969, his vision, assisted by good, pebble-shaped (hence his nickname, Pebbles) spectacles, was sufficient for full-time driving, studying taxi drivers’ ‘knowledge’. His first trip to Penton Street saw him meet one of the most knowledgeable London taxi servicemen, examiner Mr Wicks.

Interviewing comprised two stages: firstly, one-to-one, where the candidate’s general character, including any police record, was discussed. Grant could not claim Al Capone status but had once been fined 10s for carrying a friend on his bicycle crossbar aged 12. He had conveniently forgotten this when completing his application but soon appreciated police-checking thoroughness. The second stage saw all applicants − about twenty − in one room with Mr Wicks, demonstrating exactly what was expected of ‘knowledgeable’ drivers.

Candidates were handed a copy of the ‘blue book’ and were taught plotting runs, using maps, two pins and cotton. Respecting the nearest route between two points being a straight line, they had to consider streets nearest to the cotton as basis for directions. The book contains thirty lists, each including twenty-five runs, feasible in either direction (very important, particularly nowadays with many streets one-way). Additionally, it shows four secondary points around each starting position; thus drivers must know 30 x 25 x 2 x 4 x 4, about 24,000 runs.

In addition, major points of interest, within 10 miles of Charing Cross (London’s reference point, from which distances to and from provincial locations are calculated) must be memorised. Drivers must also know basic directions from Central London to all suburbs, at least within the M25.

Mr Wicks randomly picked a student, asking: ‘Where were you born?’ ‘Ware,’ Grant replied. ‘I’m asking the questions!’ was his reaction. ‘No. Ware, Hertfordshire,’ Grant explained. ‘Where do you live now?’ Wicks went on. This time, Grant could be less ambiguous: ‘Barkingside, Essex.’ Pronouncing this a ‘Green badge Village’, Wicks asked Grant to name all turnings, left and right, from Sandringham Gardens to the Green Gate pub. Despite this being Grant’s home area, he failed, Wicks demonstrating the widest knowledge of anyone Grant ever knew.

Following this introduction, Grant’s first problem was transport. Finance was short so he approached his local bicycle shop, buying a moped previously used by ‘knowledge’ students. In dubious condition, it broke down continually, leaving him walking home. Initially he accepted this ‘job hazard’, but on one occasion, stranded in Peckham Rye, he faced a particularly long trek. Approaching Westminster Bridge, he seriously contemplated tossing the infuriating machine into the Thames, quitting the knowledge quest in favour of something less arduous.

Lengthy family discussions followed, his father-in-law finally paying for a new moped, a Garrelli. Armed with renewed hope, Grant restarted. He disliked ‘knowledge’ work, but, accepting that there were no shortcuts, he struggled across a lake of heavy mud to make significant progress in a study course equivalent to five years in law or medicine.

Monthly tests saw Messrs Finlay, Miller (former police officer) and Rance (Blue Book authority) joining Mr Wicks on the examiners’ inspection panel. As well as insisting on street and landmark knowledge, they regularly checked on character to ensure that drivers were up to the standard expected of someone deemed ‘fit to be turned loose on an unsuspecting public’. Character was Mr Finlay’s speciality − he sent shivers down students’ spines with a heavy Scottish − probably Outer Hebridean − accent, only locally comprehensible. However, when the mood took him he could produce the Sovereign’s English. His sole intention was to raise students’ level beyond redemption – only 40 per cent succeeded.

Lawrence Grant’s Metrocab, viewed from various angles. (Author)

Once qualified, Grant became a black-cab driver for nearly forty years. His marriage was blessed with two children: Amanda, born June 1971 and Dean, two and a half years later. Following the death of his father-in-law, his mother-in-law Cissie Lawrence lived with them until her death in 2006. Thus a cosy-looking family of five welcomed me in July 1995. My involvement? I will confine it to incidents relevant to the Grants and my authorship of this book.

Born in the post-war birth bulge, in early 1946, I attended primary school around Northwick Park and then Latymer Upper School, Hammersmith. I took a degree in Applied Physical Sciences (early days of Norbert Wiener’s ‘cybernetics’) at Reading University, graduating in the summer of 1967, and applied for a job in the Prudential, hoping for work on computers, my forte. The company, however, had other ideas, putting me on actuarial work. I started the examinations, reaching the Associateship in 1973 and passing my first final in 1976.

My mother’s health deteriorated through the 1970s, and she died a slow, painful death of cancer in August 1977. My father suffered a stroke in the summer of 1980, and died of a second stroke in early December. I was then involved in a very nasty court case, taking several years instead of a few weeks. Inevitably, my work became affected and after several tests, the Prudential conceded that I was in the wrong job, now being more suited to ‘arty’ subjects like creative writing. An obvious option was to move departments, but I was well known to be a very controversial character, determined to speak my mind even at the risk of upsetting people. Rather than sack me, they gave me ‘early retirement’ from Christmas 1986.

By then I had reached a reasonable standard of bridge and had already been working on my first book on the game. This was published in 1987 and my twenty-third on the subject is due to come out shortly. I have also dabbled in other interests, notably the diet and nutrition industry. My book on it, That Four-Letter Word, Diet, was published recently.

When I met Amanda Grant, we dined out to discover that, not only was there a twenty-five-year age difference but we were also miles apart in terms of academic level and general interests, notably musical tastes. It would be exaggerating to say that we were the most incompatible couple imaginable but we were not far off. Yet with all this, we seemed to get on rather well. We agreed to meet again and the rest is history. I proposed in October 1996, and we married the following June.

The book was Lawrence’s idea. He used to tell of famous passengers, Major Ronald Ferguson, Tommy Cooper and Frank Sinatra probably being the best known.

The following includes others worthy of gratitude:

Bishop, A.

Bruce, D.

Buggey, S.

Dimmock, S.

Doran, A.

Ellman, M.

Ellnor, D.

Hausenhoy, A.

Newman, M.

Parcell, D.

Peake, R.

Roth, S.

Shuster, D.

Spencer, B.

Superfine, A.

Thompson, E.

Waite, G.

Worshipful Company of Hackney Carriage Drivers

I also thank the Public Carriage Office (henceforth PCO) and several motor industry companies who have provided valuable relevant information. The National Motor Museum and similar establishments also kindly helped with time and effort. I am also indebted to previous taxi-orientated writers:

Bobbitt, M.

Georgano, N.

Gilbert, G.

Levinson, M.

Lindsay, M.

Munro, W.

Samuels, R.

Warren, P.

Danny Roth, 2015

Introduction

‘Taxi! Taxi!’ A well-known cry heard everywhere – even the musical My Fair Lady started with patrons emerging from Covent Garden Opera House, eager for transport home. But how many appreciate the history and behind-the-scenes background of this apparently simple transport mode?

Old adages indicate that only when one starts learning does one realise the alarming level of one’s ignorance. When I started researching taxi history, volumes of available literature progressively increased and I wondered whether I could ever finish – researching, never mind writing.

To start with basics, one explanation pronounces ‘taxi’ joining our language in the eighteenth century, a German nobleman, Baron von Thurn und Taxis, running a mail-delivery-service company using a primitive device for measuring distances travelled by carrier coaches, the taximeter’s forerunner.

Countless external factors are influential – each pulling in its own direction – causing limitless strings of problems. Simple illustrations will clarify. A taxicab of given size must provide adequate room for driver, passengers and luggage. Increasing the driver’s room for his comfort involves reducing space for others and vice versa. The obvious solution seems to be to increase the vehicle’s size, but now we run into increased manufacturing costs, maintenance, insurance and running, with larger vehicles producing lower mileage per litre of petrol. There are also increased parking problems, countless legal restrictions, which vary with government, time and place … need I continue?

I must first list relevant parameters, briefly discussing each, then, as history progresses, explain how each had its say and how the service has steered through the various minefields. The taxicab world even has its own language. The term itself might derive from Greek taxideyo, to travel – another explanation. Appendix 1 shows a glossary.

Vehicles themselves have changed over time from ancient history’s rivercraft before the wheel’s advent, to horses and motorcars. I shall outline designs, manufacture, maintenance and safety before considering fuel, ranging from hay to petrol, and distance/time measurement.

Vehicles are operated by drivers – boatmen, horsemen, taxicab drivers or ‘cabbies’. I shall consider necessary qualifications and how he (i.e. he or she) has performed and behaved over time. Drivers can be self-employed but often work for companies, each having their story. Passengers vary from fitness fanatics to those with special needs, blind and disabled. I shall contrast treatment of various users, from attractive young ladies to sprint-champion bikers and from drug dealers to entertainment stars or senior politicians.

I then need to consider environment – qualities of river, track, or road – how to handle various weather conditions from temperature extremes to those of ice, flood and dryness. In addition, I look at off-road conditions, drivers’ facilities for food, washing, etc., unions and welfare organisations.

Administration includes financial balance sheets, which tabulate collected fares, including tips, against costs, fuel, maintenance, insurance, tax, uniform where applicable, advertising and communication – lists are endless against a background of economic troubles, inflation, interest rates and so on. These all deserve books to themselves and then there is legality. Laws vary not only with time and place but also apply to financial elements and taxi design, general driving, licensing standards and qualifications.

Thus taxi history is effectively a series of stories, mostly running parallel but frequently crossing paths. It is therefore impractical to work chronologically without awkwardly jumping between tracks every paragraph. I discuss general periods and within each, tell a number of stories while emphasising places at which paths cross.

It will be convenient to consider six periods, noting some inevitable overlap, particularly legally:

Up to 1834

1834–97 Victorian era

1897–1918 when the motor gradually took over from the horse to the First World War armistice

1918–45 interwar period and the Second World War

1945–61 immediate post-war period

1961–present day, modern era from the appearance of minicabs

I also consider the future, bearing in mind that lotteries or football pools may be considerably more reliable.

1

Early Days:Up to 1834

As indicated, if licence permits description of rivers as ‘roads’ and boats as ‘taxis’, vague evidence dates back to 4000 BC when Ancient Egyptian boats carried passengers along the Nile. More confidently, advancing to 2000 BC, Cairo’s Museum boasts boating exhibits.

Further clues emerge from considering the necessity for some sort of taxi service. Cities of significant size existed from 3000 BC; however, most were small and densely populated and local journeys could usually be walked, the slow pace of life demanding little hurry. Only the late Middle Ages saw cities grow to the degree that occupants lived and worked more than walking distance apart, necessitating transport. Most had populations below 5,000, possible exceptions being London at just under 18,000 around 1100, approximately doubling by 1400, and Paris with 6,000 in 1300, increasing to five figures a century later. Around then, only Ur of the Chaldees was more heavily populated, perhaps 25,000 to 30,000 with sardine-style crowding.

However, towards 1600, trade, commercial development and city growth necessitated and brought about marked changes for urban dwellers, notably expanding around harbours and along rivers. In Britain, Renaissance and Reformation periods brought in, for the first time, industries like herring fishing, iron and steel, and cloth production to cities. Cultural mobility increased significantly as long-distance travel enabled craftsmen, philosophers, artists and others to spread their talents in centres of government, industry, learning and entertainment. Increased populations and land-area use, building of large residential properties, streets, bridges and the establishment of parks and gardens, characteristic of the late sixteenth century, resulted in higher growth rates. These dramatically exceeded those of previous periods as suburbs were absorbed, necessitating public transport. However, environmental conditions needed improvement. At least up to the seventeenth century, roads were terrible – cobblestones being frequently punctuated by pits, trenches and mud. Thus, unless it was inconvenient to use the Thames, then easily the best route, it was probably quicker to walk than use wheeled transport. At best, this would be extremely uncomfortable, passengers feeling as though they were progressing on very eccentric elliptical wheels.

The Spanish Armada year, 1588, saw a thanksgiving service for deliverance of the conflict’s survivors held in St Paul’s Cathedral, horse-drawn carriages being laid on for congregants. The coaching company’s licensees paid £50 per annum, then considerable, for the privilege of running their service.

With fuel-powered motorised transport still three centuries away, the principal form of land transport was equestrian with the key name Hackney. The term may originate from the fourteenth century with several explanations. One states that horses, bred in pastures in the East London borough of that name were led through (appropriately named) Mare Street to Smithfield Market. Another quotes the ancient Flemish/French term Hacquenée, a spotted, patched or ‘dappled’ grey or dark-coloured ambling nag, customarily ridden by ladies. The breed was developed in the eighteenth century, crossing thoroughbreds with large-sized Norfolk Trotters, an important example being mid-eighteenth-century stallion shales. About 14–15 hands high, these horses have heavy muscles, wide chests and impressive bodies with arched necks. They display high-stepping flashy trotting and, highly strung, must be handled with experienced care by qualified trainers.

Carriages and coaches, usually waiting outside inns and taverns, were then also named Hackneys and, although hardly describable as either sleek or comfortable, they boasted the sturdiness necessary to run on the adverse road conditions of the day. The first record features the Earl of Rutland ordering a coach in 1555. However, sixty-odd years passed before further examples emerged. The 1620s saw coaches operating and in 1633, one Captain Baily, a retired sea captain or ‘matelot’, who served under Sir Walter Raleigh on South American expeditions, bought four coaches and employed drivers, appropriately equipped with livery. They stood in London’s Strand next to St Mary’s Church and outside the Maypole Inn. This was the earliest recorded ply for hiring (nowadays ‘cruising’). Areas congregated by Hackneys, nowadays termed ‘stands’ or ‘ranks’ were named ‘standings’, and first appeared in 1634.

The year 1639 saw the Corporation of Coachmen licensed to ply for hire in London. Early coaches were usually two-seaters, pulled by one horse. Most originally belonged to noblemen, who had sold them off on falling into disrepair. Their poor state on acquisition earned the nickname ‘Hackney hell carts’. By about 1650, there were over 300 larger versions, still two-seaters but driven by two horses, the driver mounted on one. They were described as ‘caterpillar swarms of hirelings’ congesting traffic in narrow streets. A 1654 parliamentary Act officially limited the number permitted around London and Westminster to 300, authorities relenting to 400 in 1661, then 700 by 1694. Around 1650, Cromwell’s era, the Worshipful Company of Hackney Carriage Drivers was established, recognised as a City of London Livery company from 2004.

Another parliamentary Act, passed in 1662, specified that horses (stallions, geldings or mares) must be at least 14 hands high. Nowadays, horses below 14 hands 2in are legally deemed ‘ponies’.

Hackney drivers seldom owned their coaches, preferring leasing. A well-known lessor was Thomas Hobson of Cambridge who earned immortality by placing horses he wanted used in the first stall, effectively giving drivers ‘Hobson’s choice’. Cab operators were mainly from the equestrian business, typically livery stable keepers or ‘jobmasters’, who, in addition to cabs, ran hearses and coaches for private purposes like mourning. Probably best known was Thomas Tilling, supplying horses to London’s Fire Brigade, Members of Parliament, the Salvage Corps, and tram companies among others. Most other operators were smaller companies.

Of the comfort improvements attempted, most notable was the 1660s introduction of glass windows. They had appeared much earlier on private coaches, the best-known belonging to the Spanish emperor Ferdinand III, providing his wife with a glass coach from 1631. However, they were liable to break, as vehicles bounced on uneven road surfaces, and were expensive to replace. Diarist Samuel Pepys, reported paying £2 for a single pane, a huge amount of money in 1668.

As taxis became more significant transporters, specific legislation was inevitable. Industrial legal participation can be traced back at least to King Richard I’s accession in 1189. However, the Hackney was first to come under serious transport legislature. In 1634, Charles I, objecting to traffic congestion and to Hackneys impeding the path of royal and aristocratic carriages, tried to reduce numbers by introducing competition − sedan chairs.

These were already popular amongst the continental well-to-do but unknown here until the King, accompanied by his favourite, George Villiers, Duke of Buckingham, travelled to Spain in a failed attempt to arrange a marriage with their King’s daughter, the ‘Infanta’. Charles was impressed with sedans and insisted on their introduction here. Buckingham was first to be carried on London’s streets – the King’s present. One Sir Saunders Duncomb was given royal exclusive rights to rent them out. The chair was originally carried on the bearers’ shoulders (considered slave labour), but it was unpopular in England until a century later when a newly designed version arrived, portable at arm’s length – now the carriers’ arms pointed downwards. Either way, they hardly alleviated congestion.

Hackney operators protested (the usual welcome to newcomers – minicabs suffered similarly 300 years later) and Hackney numbers carried on increasing regardless. Nonetheless, rivalry was bitter and by 1711, when Hackney licences were increased, firstly to 800, later to 1,000, some 200 sedan licences had been granted by Hackney Coach Commissioners, increased to 300 in 1712. Despite their being more expensive, 1s a mile against Hackney’s 8d, and slower, being restricted to the bearer’s walking pace, the sedan was popular, offering the advantage of having tough fellows as carriers, who, for a small tip, would guarantee passenger safety against pedestrian robbers, muggers or, as they were known, ‘footpads’ (unless bearers cooperated with criminals; now the chair would commonly be set down while they enjoyed a refreshing tankard).

In 1635, a Royal Commission was established for Hackneys’ regulation. The King insisted on licensing drivers. His proclamation of mid January 1636 allowed up to fifty Hackney carriages to ply in the London area but barred them from the Cities of London and Westminster unless they entered the area intending to take passengers at least 3 miles outside, in practice to country homes. Aldermen were expected to enforce the limit. Also no private individual was allowed to keep a coach in City confines unless he had four fit and able horses available for His Majesty’s war service. He further complained that Hackney coaches broke up street pavements and increased demand drove up prices of hay and other dried animal food, ‘provender’.

However, modest police numbers made enforcement difficult. Nevertheless, all this threatened the industry and distressed Hackney men petitioned in June 1636. They requested that 100 be allowed to form a corporation for unimpeded plying. They argued that full-time operators in London scarcely numbered more than 100 anyway and that traffic congestion was actually caused by coaches hired out by speculative shopkeepers. Petitioners offered £500 per annum for this right but the King refused. Two years later, they ‘improved’ the offer by volunteering to keep fifty men and horses readily available for military service. That was also rejected but the Hackneymen ignored the King, escaping unscathed, primarily because he had other problems, notably desperate money shortages, leaving him dependent on unsympathetic Parliamentarians. In 1639, licence was granted to the Corporation of Coachmen.

From 1654 and the start of Cromwell’s rule, Parliament placed Hackney legislation with the London Court of Aldermen; they made by-laws, restricting Hackney numbers in the London/Westminster area to 200 or 300 (historians differ) and also, as before, requiring licensees to have four horses available per Hackney. Around then, Cromwell also established The Fellowship of Master Hackney Carriages or ‘Coachmen’. The coachmen, Civil War Roundhead combatants, were licensed at £2 annually. However, political and religious disharmony forced him to disband it in 1657. Nonetheless, taxi driving had now become a recognised profession.

The coronation year 1660 saw King Charles II forbid, by proclamation, street plying. Apparently little notice was taken; diarist Samuel Pepys proudly recorded breaking the rules from the first day. In 1662 the King appointed commissioners to oversee registration and licensing of coaches, the permitted number rising to 400.

This new Act replaced that of 1654. Restrictions imposed typically included one that no licensee could have another trade and that horses needed 14 hands minimum height, ponies being deemed insufficiently strong to pull heavy and cumbersome coaches. The Cavalier Parliament also taxed each Hackney 20s plus a registration fee and a £5 licensing fee for street damage, sewer repairs and by-way improvements. However, this was discontinued from 1679, there being no sitting Parliament to renew legislation (until re-imposition in 1688, following the first major trade enquiry led by Sir Thomas Stamp). The permitted number now rose to 600 until new 1694 legislation added a further 100.

The year 1679 saw early signs of the ‘Conditions of Fitness’ concept on Hackney coaches, referring specifically to drivers’ seats’ size. Wording mentioned the ‘perch’ of every coach to be 10ft minimum, to have cross-leather braces and be strong enough to carry at least four persons. With the rule applying to all new and second-hand coaches, many nobility cast-offs now serving as Hackney coaches, needed modification. However, the insignia of former owners were kept on the doors. From 1654 to 1714, Hackneys displayed registration numbers on both coach doors. Subsequently, they were displayed on a metal plate nailed to the rear door – something that holds today except that computer-generated, forgery-proof plastic versions are used.

Following the Great Plague of 1665, an authoritative decree or ‘ordnance’ was enacted, under which Hackney coaches carrying passengers to shelters and/or hospitals for the infected – ‘pest houses’ – needed five days’ airing before further use. The Great Fire of London in 1666 resulted in many streets being rebuilt and widened for easier manoeuvrability. Drivers could now sit on coach boxes rather than riding horses. Larger coaches could now be used, including many nobility discards.

Strangely, this has been repeated recently: discarded Rolls-Royces are often used as hire cars. Users enjoyed the ‘status’ of riding in vehicles formerly belonging to ‘betters’. In 1685, some women donned masks and hired a coach displaying a well-known aristocratic crest to drive through Hyde Park. On seeing several rich and famous people riding in private coaches, they started a stream of abusive behaviour. The resultant complaints led to Hackneys being banned from the park for two years. Following several more instances, the ban was reinstated in 1711, this time lasting until March 1924 when ex-cabbie Ben Smith, now a Labour MP, hired a cab, driving there for a ‘lap of honour’.

With Hackney coaches flourishing, more companies wanted to join, increasing pressure for further licences. However, ‘who you were’ rather than your capabilities took priority. For consideration, prospective licensees needed a sitting MP’s recommendation, implying that friends, associates and former servants not only dominated but appreciated monopolistic advisability of limiting numbers. Inevitably, bribery was rife; licences (standard charge £5) changed hands for £100 − like stadium-ticket touting. After standardisation under William and Mary in 1694, Parliament took control and the Hackney Carriage Office, along with five commissioners answerable to Treasury Lords, was established to control trade regulations. The Ways and Means Act of 1710 was one example. (Actually, the purpose was funding war with France; one account quotes £20,000 needed for trade organisation over seventeen years while collected fees totalled £82,000).

That year’s licence fee was legally increased to £50 with twenty-one years’ validation. However, much illegal plying continued, notably in night-time London. Unlicensed men exploited a loophole by moving to towns, typically about 20 miles away, then entering the area ‘plying as stagecoaches’. When they reached London’s streets, they could ply in direct competition to legally licensed coaches – similar to taxi-minicab warfare. If anything, violence then was more intense. There were numerous complaints against Hackneymen who used tactics like impeding customers from entering shops and picking fights with argumentative tradesmen; occasionally even aristocrats were involved. Thieves’ attacked coaches, knifing the back open, after which passengers could be robbed of anything, even wigs.

Nevertheless, opposing forces operated. Generally, authorities showed greater interest in honesty than in drivers’ and horses’ ability and, from its formation in 1698, the Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge published specially written moral pamphlets (‘tracts’) applicable to worker groups whose morals and behaviour were poorly viewed. These also applied to sailors, innkeepers and soldiers. London’s City Mission has worked in this area ever since.

The year 1695 saw the first Commissioner for Licensing appointed, numbers increasing to 1,000 by 1768. That year saw King George III create a commission regulating Hackney coaches. Its functions included approval of locations for standings, licensing of caddies or ‘cads’ to water the horses, care of Hackneys in drivers’ absence and passenger assistance. Coachmen had to give way to ‘persons of quality and other coaches belonging to “gentlemen”’, being fined £5 for indiscretions. A further 100 licences were issued by 1805 but complaints of poor late-night theatreland availability abounded.

The early nineteenth century (possibly 1823) saw French cabriolets make their London debut, their name being shortened to the (many thought) vulgar-sounding ‘cab’. Eight were licensed initially, four more joining later. Painted yellow, they stood for hire in Portland Street. They were popular with the public, but in-force regulations granting exclusive rights to Hackney owners inevitably hindered their expansion. Hackney owners opposed their rivals, predicting a limited future. However, in 1805, nine licences were granted to a couple of MP’s. Several Hackney operators, observing the popularity and success of their fast-travelling competitors, impatiently petitioned to have their licences transferred to cabs. However, cab operators were men of high social standing, using their considerable influence for maximum obstruction. Consequently, such transfers were not granted until 1832; soon afterwards several hundred cabs rode London streets.

Two new Hackney cab versions then appeared. Spring 1823 saw twelve purpose-built but cumbersome Hackney coaches operated by David Davies of Mount Street, Mayfair. Originally named ‘covered cabs’, this introduced a curtain protecting passengers against wind and rain. A later improved variant, two-wheeled and lighter, earned the nickname ‘coffin cab’, being shaped accordingly. Their rank was near the Oxford Circus end of Great Portland Street. Painted yellow and black, they became very popular, charging two-thirds of competitors’ fares. Other trials had poorer success. One, in 1823, was an enclosed four-wheeler, named Clarence after the Duke (King William IV from 1830) but also known as the ‘growler’, detailed later. Reasons are debatable, candidates ranging from the noise it made as it traversed irregular cobblestones to their drivers’ temperament.

William IV’s reign saw major legislative overhaul with 1831’s London Hackney Carriage Act. This ended 177 years of transport history, during which the Hackney carriage was the only public transport form recognised apart from the sedan chair. The Act cancelled many previous regulations (applicable to Hackneys as distinct from stage coaches), abolishing the Hackney Coach Office and transferring licensing power to the Commissioner for Stamps (in 1838 this was transferred again to the Commissioner for Excise). ‘Stagecoaches’ were so called because originals were Hackney carriages travelling in stages – short distances along a fixed route, picking up passengers at set stopping points, nowadays termed ‘stops’. They were the precursors to modern omnibuses.

Numerical limits on operating Hackney carriages’ were lifted. Responsibility for issuing licences approved by the Commissioner, collecting revenue, making by-laws regulating conduct of proprietors, trade, etc. and offence and dispute adjudication passed to Metropolitan Police magistrates. In 1838, licence issue became the responsibility of the Registrar for Public Carriages, appointed by the Secretary of State. In 1850, when that office was abolished and the Public Carriage Office established, a Commissioner, an MP, acting under the Secretary’s authority, assumed all registration duties – taxicab and rank licensing, regulation in the Metropolitan Police Area and City of London, and lost property redemption or disposal. Area division details are in Appendix 9.

The PCO opened in April that year in Great Scotland Yard, Whitehall Place (annex of New Scotland Yard, from which it was nicknamed ‘The Yard’; some say ‘The Bungalow’), subsequently moving to 109 Lambeth Road in 1919, then 15 Penton Street near King’s Cross from 1966. (It has, however, terminated many of its maintenance activities since March 2007; nowadays cabbies take vehicles to SGS Maintenance). Around then, registered cabs under regulation numbered around 4,500. Office management and control remained unchanged up to 2000 (19,500 taxis then licensed in the areas and 23,000 drivers), but from early July that year it became a government agency, parting from the Metropolitan Police Service. Control then passed from the Department of the Environment and Region to the ‘Transport for London’ section of the new Greater London Authority, directed by the new Mayor of London. He has powers under the Greater London Authority Act to dispense with outdated regulations like the 6-mile limit; further details in Appendix 2.

It was anticipated that future years would see it take control of regulation of unlicensed minicabs and hire cars. Minicab licensing became legally compulsory from the summer of 2004. Plans anticipated licensing under three headings: operators, drivers and vehicles. The major change forecast was that, whereas originally considered a separate entity, taxis would hence be deemed part of an integrated transport system, including buses and the Underground.

Sadly, many records disappeared in the two moves. Early days saw horse-drawn cabs as the only recognised form of Hackney carriage; appointed inspectors were required to have intimate knowledge of vehicles, equestrian diseases and associated problems to be able to issue certificates of fitness as per 1843 legislation discussed below.

Defining the area under these authorities, the original London Area Act was enforced from 1829, the formation year of the Metropolitan Police, taking over traffic control from appointed parish officers – ‘beadles’. Amusingly, while the intention was ‘improvement’, complaints about hour-long delays were frequent with notorious police arm signals misunderstood by frightened horses. Originally, the area covered was defined as the Cities of London and Westminster but in 1831 this was redefined to a 5-mile radius around the General Post Office. In 1838, the radius was doubled and from 1843 to 1895, to the City and Metropolitan Police District.

Previously short-stage coaches could only legally operate on fixed routes beyond the area of the Bills of Mortality, defined as that within which return of parish deaths were drawn up as a ‘Bill’ and accounted for by the Worshipful Company of Parish Clerks. The area extended east–west from Whitechapel to Marble Arch and north–south from Islington-Hackney to Southwark. Within it, 1,200 Hackney coaches had plying licences whereas short- and long-stage coaches could only collect passengers at a central point, dropping them outside the area. This arrangement had stood since the Elizabethan era closed in 1603, but now London streets were open to everybody. Major bus companies were formed, eventually merging as London Transport. Other notable names were Thomas Tilling and Goode and Cooper of Brixton, lasting until the 1970s.

So … cab or coach? Clearly cab travel was faster but at the expense of comfort and safety. Cab drivers were markedly less safety-conscious than their counterparts, keen to show off speed, even if that meant frequent collisions with lamp posts or other vehicles. Horses fell regularly, usually propelling passengers on to the street, putting many off. Customers were restricted to youths and those who thrilled in risk-taking. Dress-conscious men – ‘dandies’ – used to flaunt their manliness by boasting of accidents. Criticisms were thrown in both directions. The coach drivers wondered why anyone was prepared to risk their neck for a few minutes’ saving, while cab drivers derided coach horses’ ‘walking’ pace.

Such public conflict had begun around 1832 when a paper entitled The Cab started but proved a literary rather than trade journal, capitalising on current cab popularity. The trade waited until the mid 1870s for its own journal, The Cabman. By about 1900, several others, devoted at least partly to the trade, had arrived and departed, notably Cab Trade Gazette, Cabmen and Omnibus News, Hackney Carriage Guardian and Cabmen’s Weekly Messenger.

The Act of 1831 also regulated drivers and licensing; hours and days of work were limited; a code of behaviour forbade refusals, abusive language and reckless driving (alcoholic or otherwise). Drivers were also instructed to avoid blocking traffic and to be honest, charging passengers correctly and returning lost property. They had to request on-board passengers’ permission before accepting additional clients.

Refusing and bilking (runaway cheating) passengers have plagued the industry to the present. It’s mistaken to think that offenders were poverty-stricken or other low-grade individuals with no conscience about a free ride. In 1695, nobody less than the King and Queen, William and Mary, hired all London’s Hackneys to take their entourage home to London after landing at Margate from a trip abroad. The charge came to £2,000 but only a modest payment was made. The remainder is still outstanding!

In 1832, Edward W. Boulnois introduced a new small, box-like cab, a two-wheeled, enclosed version, the driver sitting on top and in front of his passengers, sitting facing each other. Their door was rear-mounted, a serious design fault; a dishonest passenger could easily alight quickly and run off. The cab, originally termed ‘backdoor cab’, ‘duobus’ or ‘minibus’, became known as the Bilkers’ cab and soon disappeared. A further version was named ‘Victoria’ cab shortly after she ascended the throne in 1837. This was a lightweight four-wheeler with a low-sweeping cabriolet-type body and collapsible hood, seating two passengers with an elevated driver’s front seat. Sometimes known as ‘fly’ cabs, these were popular with ladies.

Around then, came the brainchild of designer Mr Harvey of Westminster, the tri-bus. He had been licensed since 1814 but now introduced refinements. With room for three passengers, the driver’s seat was offset, allowing him control of the passengers’ door. Two additional frontal small wheels were added so that if the horse stumbled or fell the cab would land on them rather than awkwardly pitching forward. Finally, there was even a quarto-bus, designed by Mr Oakey, but those aside, the hansom and growler virtually monopolised the scene until internal combustion engines arrived around 1900.

2

The Victorian Era:1834–97

T he introduction of hansom cabs came in 1934. Joseph Aloysius Hansom (1803–82), originally from York, grew up in Leicestershire, taking apprenticeship in his father’s building business. He later became noteworthy as a young architect, designing Birmingham Town Hall. Sadly, this venture proved financially disastrous so he turned to another business, cabs. The hansom cab, originally known as the ‘Hansom Safety Cab’, was patented that year. A square frame ran on two huge 7ft 6in wheels with a front driver’s seat and room behind for two passengers. The design aimed for maximum speed consistent with safety, the centre of gravity being as low as practical so that cornering spelt minimum danger. The weight was also minimised for comfortable pulling by one horse for greater economy. (Larger four-wheeled coaches needed at least two.) Early variants seated two passengers (three at a squeeze) with the driver on a sprung seat. Weather protection was afforded by the cab exterior and by folding wooden doors, which enclosed feet and legs, providing a barrier against splashing mud. A door-mounted curved fender warded off stones thrown up by horses’ hooves.

In 1836, John Chapman arrived. Initially a clockmaker and lacemaking machinery manufacturer, he subsequently became an authority on Indian finance and an aeronautics trade pioneer. As a London cab operator with the Safety Cabriolet and Two-Wheel Carriage Company, he helped rectify faults with five prototype designs. Smaller wheels were used with the driver’s seat moved back to improve balance. He now entered through a frontal folding door. A trapdoor and sliding roof window afforded easy driver-passenger communication. A cranked axle, passing under the vehicle, was originally used, later replaced by a straight axle, even if that meant cutting away part of the body beneath passengers’ seats. This cab, already popular in London from 1836, survived until motorisation. In 1873, further improvements were made by coachbuilder F. Forder, who then successfully introduced it abroad.

The Safety Cabriolet and Two-Wheeled Carriage Company purchased Chapman’s patent in 1837, remaining active for about twenty years. It put out fifty new cabs, subsequently incorporating Hansom’s patents and Chapman’s improvements into a new ‘Hansom Patent Safety’ Company. Using Hansom’s name, with Chapman probably more appropriate, proved an expensive commercial mistake. Design problems still abounded. The framework, weighing about 4cwt, or just over 200kg, was unsprung so that if the cab hit an obstacle the horse could not proceed; either the weight was thrown forward on to his back or forces could act vertically so that the weight was now on the belly band. It was also difficult for passengers to squeeze out past large, often muddy wheels.

Inevitably, imitations soon appeared, prosecutions being showered on copiers. However, despite the plaintiff winning consistently, this proved to be ‘good money after bad’, offenders being of little or no substance. Typically, £2,000 spent on legal action ‘earned’ £500 in damages or compensation, leaving the company little alternative but to abandon exclusive rights to use ‘Hansom Patent Safety’, which appeared on all cabs of this type thereafter. Users were usually unable to distinguish between genuine and fake, but drivers were well aware of the distinction and treated pirate drivers contemptuously, calling them ‘shofuls’. The word, variously spelt, is Jewish ‘slang’ for worthless or counterfeit material, rubbish. Jewish drivers, employed by the original company, so described rivals but it eventually became slang for hansom cab.

The 1840s saw growlers appear. Four-wheeler Hackneys, around from the mid 1820s, had been popularised by the General Conveyance Company from 1835. This example, back wheels larger than front, seated two passengers in an enclosed area with room for a third on a box beside the driver. They were slower but more robust than hansoms and greater capacity made them favourite for heavy-luggage carriers. This was secured by a rear rail, as proposed by designer Tommy Toolittle. Its considerable noise, odour and tough springs, which gave a ride resembling one over endless strings of closely-placed sleeping policemen, earned its nickname of ‘maid of all work’. By contrast, a future Prime Minister, Benjamin Disraeli, proved a hansom fan with the friendlier description: ‘Gondola of London’.

Growlers mostly worked between railway termini. But railway authorities allowed only limited numbers on external ranks, and then only on payment of ‘privilege fees’. On occasions when supply failed to meet demand, staff reserved the right to call in extra outside cabs – ‘bluchers’ − after a Prussian Field Marshall Battle of Waterloo combatant known for always being the last to arrive on the battlefield.

Dispute was inevitable but railway companies argued that their rules ensured respectable cab standards, allowing them greater control over drivers. Snobbish discrimination suggested by that first point caused particularly hot rebuffs. Cabbies argued that privileged proprietors kept their best cabs away from stations, fearing knocking about by heavy luggage. One major proprietor insisted that it cost 12.5 per cent more to maintain privileged cabs than others. Furthermore, station interiors were dark; with passengers more concerned about quick departure than cab quality, they were ideal places to send modest-standard cabs. Il-feeling persisted until the privilege system was abolished in 1907.

During this period, Hackney popularity also plummeted. The public became increasingly intolerant of carriages’ filthy condition and drivers’ hostility, dishonesty and recklessness. (Even with honest charging, most considered them too expensive). The 1840s saw barely 400 in London, public pressure intensifying for firmer legislation. Within a decade, they virtually disappeared, a handful remaining until 1858. Hansoms and growlers markedly increased overall cab population. Typically, 1855 saw London’s licensed cabs numbering just below 2,800. This increased towards 4,300 by 1860, further increases following. However, while hansoms dominated London, provinces thought otherwise. Typically, in 1880, Manchester had about 100 hansoms, with four-wheelers exceeding 360; Newcastle, still further behind, had as many two-horse cabs as singles. Many seaside resorts preferred Victorias.

As old Hackney coaches retired in some disrepute, one bitter critic was Charles Dickens. One London magazine published an article mentioning wet straw, broken windows and cushions on which shoes had been cleaned, fever and convict carrying to deportation ships. Another mentioned a ‘great lumbering square concern of dingy yellow colour like a bilious brunette with very small glasses but very large frames’. It talked of panels ornamented with faded coats of arms – dissected hat-shaped – red axletree, green wheels and old grey-coat box-coverings. Even horses were verbally abused.

Notwithstanding Dickens’ literary expositions on the period’s poverty, population and wealth grew, as did consequent cab demand. The industry responded in 1855 with around 2,500 licensed cabs, increasing to about 4,300 within the next five years. Hackney coaches and carriages were still being produced with new designs always welcome. Over this period, there had been many attempts for design improvements of both two- and four-wheeled cabs. Typical examples included Harvey’s New Curricle Tribus, appearing from 1844 with a rear entrance. The driver’s offside seat allowed him easy door opening/closure. It could thus carry three passengers and be converted to a single-horse variant. It had frontal, rear and side windows and thus appeared an improvement on the hansom with increased weather protection. However, possibly overweight, it never caught on. Others included Evans, whose principal feature was under-springing of shafts, and Felton, a vague hansom copy.

Early July 1868 saw the Society of Arts offer gold and silver medals for the best coach for two, open and enclosed, and similarly the best carriage for four. Response was minimal, the offer being abandoned until 1872. That year, cab proprietors, previously reluctant to incur entry expenses, indicated greater interest with cash prizes offered. The Society agreed, withdrawing medals in favour of £60 first prize for the most improved cab of any description. The runner-up would receive £20 and the next two £10 each. The committee specified that cabs had to be working for at least three months and be ready for exhibition by 1873. Panellists included representatives of the aristocracy, services and the trade.

Sixteen entrants left them unable to agree an outright winner, sharing the prize money between Mr C. Thom of Norwich, Mr Lambert of Holborn, Forder and Company, coachbuilders of Wolverhampton, and Messrs Quick and Mornington of Kilburn. The four ‘winners’ were presented to the Prince of Wales (later Edward VII) at Marlborough House. His Royal Highness, a man of decision, ordered himself a Forder. The Forder cab’s principal improvement feature was the straight axle. The driver’s seat was also raised to 7ft above ground level, his weight counter-balancing the shafts’ for perfect balance. Thus maximum weight was taken off the horse for higher speed and manoeuvrability. The following years saw Forder hansoms adopted extensively in London, the Society feeling justified that its pecuniary offer had earned credit.

This success prompted the Royal Society to hold a special exhibition in October 1875, at Alexandra Palace. A prize of £200 was offered to the best cab and the driver claiming the longest employment stint with one employer. To qualify, the winner had to be free of charges of cruelty to his horse, drunkenness, reckless driving or similar misdemeanour. The press, notably Punch magazine, felt sure that finding a winner would prove impossible! However, Forder won again with their 15–17mph hansom. Nevertheless, since 1843, as well as Harvey’s patented seat attachment, several others had patented improvements; most notable was Clark’s 1868 folding-hood invention.

The London Improved Cab Company proved most successful. Their depot at Gray’s Inn Road, Holborn incorporated shoeing forges and repair shops. From Chelsea’s stables, they operated about 300 cabs over a decade to 1894. Also solid rubber tyres were introduced on Forder cabs owned by the Earl of Shrewsbury and Talbot. These were recognised as among the smartest around London with their distinguishing trademark ‘S. T.’ surmounted by coronets above windows either side. Inclusion of such tyres implied silent cab motion (manufacturers were known as Noiseless Tyre) so small bells were attached to horses, warning pedestrians of approaching vehicles. Like most successful innovators, His Lordship earned himself considerable unpopularity with rivals, feeling obliged to change to rubber tyres themselves at considerable expense, although they earned benefits of smoother rides and treble wheel life. While the business’s ‘cab’ side was financially unsuccessful, patenting rubber tyres for other users compensated.

Other hansom variants included the four-wheeler ‘Court cab’, the driver returning to the normal rear ‘hansom’ position. It appeared from the late 1880s for about fifteen years. One other prototype from Joseph Parlour, first exhibited at the1885 Inventors’ Exhibition and subsequently developed by John Abbot of Bideford, was the 1887 ‘Devon’ cab. This seated four passengers (two facing two) with two small rear doors either side of the driver’s seat. However, few were manufactured and it was commercially unsuccessful. Similar comment applies to the Imperial Brougham, which had a movable seat and doors opening both ways, and to Floyd’s, having a forward hood (‘calash’) with front and side windows, which could be lowered in a curved line against adverse weather. This luxury was at the expense of considerable extra weight. The handful produced, decorated lavishly, were used privately by the wealthy. There was also the Prince’s cab, boasting lighter weight and good side ventilators with patent windows, and Birmingham’s bow-fronted Marston cab in 1889. Finally, a three-wheeled version was proposed in 1900 carrying four passengers, with the cranked rear axle designed to keep the body low; this, combined with the angled front door, eased access.

In 1894, Mr Thrupp of Maida Vale similarly attempted growler promotion. He offered prizes for four-wheeled cabs, insisting that candidates had to carry at least two passengers with luggage; the hood had to fold with the driver seated in front. Judges primarily sought durability with accuracy and simplicity of design and construction. Thirty entrants arrived at Baker Street’s Cambridge Bazaar, but this form of transport was facing sunset, motorisation impatiently awaiting its cue.