Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The Crowood Press

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

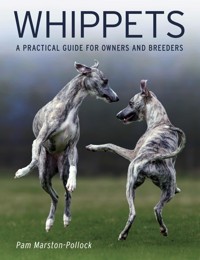

A comprehensive guide to owning a Whippet, from puppyhood to the senior years The Whippet is one of the most popular and versatile dogs and may serve as a loving family pet, competitive sporting breed or much admired, elegant show dog. Written in a practical and easy-to-follow style, this book draws from the author's lifetime of experience to provide invaluable, in-depth advice on every aspect of owning a Whippet.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 290

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

First published in 2023 by

The Crowood Press Ltd

Ramsbury, Marlborough

Wiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book first published in 2023

© Pam Marston-Pollock 2023

All rights reserved. This e-book is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 7198 4296 2

Cover design by Sergey Tsvetkov

Contents

Preface

Acknowledgements

1 History and Origins

2 Early Foundation and Influential Breeders

3 Choosing a Breeder

4 Health and Welfare

5 Temperament

6 Caring for the Adult Whippet

7 Dog Showing and Judging

8 The Whippet Breed Standard

9 Racing and Lure Coursing

10 Obedience and Other Disciplines

11 The Art of Breeding

12 Rearing a Litter

The Last Word

Bibliography

Index

Preface

Whippets have been in my life since 1967, and have given me – along with many people, I’m sure – a great deal of pleasure and have allowed me to achieve much more than I could ever have imagined, not only with successes in the show ring, but also with the opportunity to travel the world as a judge. I have had the honour of judging many beautiful Whippets, and made lifelong friends in many countries.

My intention for this book was to bring to life those early founders of the breed who so often are simply names with their kennel name in brackets. I am therefore indebted to Andy Bottomley and Penny Kastagir, who have shared their family’s photos to allow us to see previously unseen images of the Manorley and Balaise Whippets. My thanks to Ciara Farrell and Colin Sealy, from The Kennel Club’s library and collections, and Heidi Hudson, curator of The Kennel Club’s photographic collections, for their help in sourcing historical material for my research.

Also a special thank-you to Pauline Oliver, who has provided the most stunning photos; and to all those who have contributed other photographs.

I hope this book provides interesting reading and useful information in whatever part a Whippet plays in your life, and that you continue to enjoy them forever!

Pam Marston-Pollock

Acknowledgements

The main photos are by Pauline Oliver; the Manorley photos by kind permission of Andy Bottomley and Penny Kastagir; Pitmen Painters by kind permission of the Ashington Group Trustees. Other photos have been provided by Molly McConkey, Editha Newton, Amy Wilton, Steph Marston-Pollock, Linda Gore, Yulia Titovets, Cath Whimpanny (Harry Whimpanny), Angela Randall and Mary Lowe. Some historical photos are of unknown origin. I would also like to thank Pat Wilson and Sarah Thomas for their pieces on obedience and agility.

The Whippet Breed Standard is the copyright of The Royal Kennel Club Ltd.

I am grateful to have been allowed to use the following photographs by C.M. Cooke: A.H. Opie judging at Crufts in 1951; Paignton Show 1958; Bournemouth Show 1968.

Also the photo by Carol Anne Johnson of Lyn Yacoby Wright and Ch. Cobyco Call The Tune at The Kennel Club with the Crufts Best in Show trophy, along with carved wooden sculptures of Chs. Brekin Spode and Brekin Ballet Shoes.

All are copyright of The Royal Kennel Club Ltd, and are reproduced with The Kennel Club’s kind permission.

CHAPTER 1

History and Origins

Over the centuries there have been considerable exchanges between countries, not only in conquests but also in trading. There are different variations of dog that are now established breeds similar to a Greyhound type or ‘lévrier’ – lévrier being a term given to specialist groups of sighthound or gazehound, that is, hounds that hunt by sight as their primary sense, their quarry normally being the hare or lièvre. The word ‘lévrier’ originates in France. The Whippet is within this group, being a sighthound for chasing hare, or more frequently rabbits. Its origins are not definite, but to look at the Greyhound type is as close to establishing the foundation of the Whippet as we will probably come.

Going back to Roman times, there is no mention of the Greyhound specifically by Xenophon in 300BC. He wrote a Treatise on Hunting describing the traditional style of hunting using snares and nets, but two centuries later the ‘Greyhound type’ was mentioned in the writings of the poet Grattius: ‘In a thousand countries you find dogs, each with their own mentality stemming from their origin.’ He wrote about the Celts’ dogs ‘that swifter than thought or a winged bird it runs, pressing hard on the beasts it has found.’

A different type of hunting, that for the pleasure of watching hounds work, was first recognised by Lucius Flavius Arrian, a Roman of Greek ancestry; he was a close friend of Emperor Hadrian (of Hadrian’s Wall fame) around 120AD. His knowledge of dogs was extensive, and he was known as ‘the younger Xenophon’. He also wrote a Treatise on Hunting, and another entitled Cynegeticus, books detailing the types of coursing dog, their use and breeding, as well as their training and conditioning. They contain many fine details of traditional ways used by breeders through the centuries with their hunting sighthounds. He highlighted the way in which the hounds used their natural instincts, and, along with Grattius, recognised that the origin of each hound was indicative not only of its mentality but also the style in which it hunted.

Roman mosaic showing a Whippet-like hunting dog. (Bardo Museum)

His knowledge was drawn from observing both Greek and Roman sports with dogs, and he detailed their different variations: so the Greeks would run a hare along a ‘track’ made by the viewing public, the Greyhound in pursuit – a type of race more familiar to us today as Greyhound racing – whereas the Roman style was similar to the Whippets many centuries later, where the hare was released in an enclosure and then coursed and caught. Arrian was very empathetic towards his own hounds – he even detailed bringing up his own dog – and named them ‘Vertragi’. ‘Vertragi’ is derived from a Celtic word for ‘a powerful but slim dog with a pointed muzzle’. He also kept house dogs, described as ‘imported companions for the lady’, and Roman miniature Greyhounds.

The variations of the lévrier type, or vertragus, spread into many countries of Europe as a result of Celtic culture. These were specific breeds of sighthound, such as Galgos in Spain, Magyar Agar in Hungary, Chart Polski in Poland, and in the British Isles, breeds such as Tumblers, Deerhounds and Irish Wolfhounds as well as the Greyhound. However, it should be noted that there seemed to be no defined breed of Greyhound as such at this time, but more of a Greyhound type of hound. These breeds were bred and developed for hunting, their qualities and abilities ‘designed’ by the huntsman’s needs, and dependent on the terrain and climate of their country and indeed different game. Individually recognised breeds have developed, and although they are unique in their own way, many are genetically related as well as having a generic function – and as with many of them, we will never know their true origins, although modern DNA testing is now beginning to reveal some of their hidden ancestry.

Throughout history, many of these specialist breeds encountered hard times at some time for many different reasons, such as war, famine and disease, as well as the banning of hunting with a lévrier, or hare coursing, all of which resulted in a reduction in numbers, which has periodically threatened those very breeds’ survival. The Greyhound type may have provided a useful and typy outcross, not only to boost a breed without introducing uncharacteristic genes, but also, in some cases, to resurrect it. So it is not impossible that many countries have also bred smaller Greyhounds, in effect their own ‘Whippets’. The older version of The Oxford English Dictionary’s definition of a Whippet is ‘a crossbred type of Greyhound’. The Whippet has now been recognised as a breed in its own right for over a hundred years, but has been redefined, with the updated version being ‘a small, slender dog similar to a Greyhound’.

Early Mentions in History

The Master of Game, written in 1413 by Edward of Norwich, the 2nd Duke of York, is thought to be the oldest translation of a description of the hunting chase. In Mary Lowe’s book The English Whippet the following quote describes the advantage of having the right hound for the right quarry: ‘The good greyhound shall be of middle size, neither too big he is nought for small beasts and if he were too little he were nought for great beasts. Nevertheless whoso can maintain both, it is good that he hath both of the great and of the small and of the middle size.’ Is he speaking of the early days of the distinct Greyhound, Whippet and Italian Greyhound?

John Caius, also known as Johannes Caius, was an English physician and second founder of the Gonville and Caius College in Cambridge in the sixteenth century, now known as Caius College. He wrote De Canibus Britannicus, which identifies many breeds or types of dog, describing their physique and function in great detail. He possibly gives the first mention of a Whippet, but then called a ‘Tumbler or Vertragus’. He says:

This sorte of Dogges, which compasseth all by craftes, frauds, subtelties and deceipts, we English men call Tumblers, because in hunting they turne and tumble, winding their bodyes about in a circle wise…these dogges are somewhat lesser than the houndes, and they be lancker and leaner, beside that they be somewhat prick eared. A man shall marke the forme and fashion of their bodyes, may well call them mungrell Grehoundes if they were somewhat bigger. But notwithstanding they counteruaile not the Grehound in greatness, yet will he take in one day’s space as many Connyes as shall arise to as bigge a burthen, and as heavy loade as a horse can carry, for deceipt and guile is the instrument whereby he maketh this spoyle, which pernicious properties supply the places of more commendable qualities.

These first descriptions not only confirm an early existence of the Whippet, but also recognise their working abilities. There were still some writers into the mid-nineteenth century who refused to treat them on an equal footing to other sporting dogs, but some of the first popular dog books eventually did recognise that the popularity of the Whippet warranted mentioning, albeit in less than complimentary words. In the 1879 edition of Vero Shaw’s Illustrated Book of the Dog, he famously said:

The Whippet or Snap Dog, as it is termed in several of the Northern Districts of the Country, may scarcely be said to lay down claim to be considered a sporting dog except in those parts, where it is most appreciated. The Whippet is essentially a local dog and the breed is little valued beyond the limits of the Northern Counties. In these, however, the dog is held in high respect and its merits as to the provider of sport are highly esteemed.

Cultural History

In England, the Whippet has always been described as a ‘poor man’s Greyhound’ or ‘poor man’s racehorse’, stemming from the early 1800s. The workers in the coal-mining communities of the north-east of England, Cumbria, Yorkshire, South Wales and Nottinghamshire, as well as the cotton mill workers of Lancashire and Yorkshire, bred smaller Greyhound types to supplement their food supply as well as providing a sporting pastime such as rag racing or coursing. The Whippet may have no ancient lineage that we can boast of specifically, or none that gives a clear and direct route that the breed has taken through the ages. Certainly in the early nineteenth century there were no pedigrees or other records that show its origin, apart from scant anecdotes.

In fact our breed’s heritage is quite modern, and it was the early show-goers who finally gave the Whippet identity. The official recording of pedigrees was not begun until The Kennel Club recognised the breed in 1890. In order to further preserve the Whippet as a specific breed, The Whippet Club was officially registered in 1899. Until this time, many exhibits at shows were of ‘unknown’ parentage and were often entered as crossbreeds.

The original communities that owned Whippets were working class. The practice of poaching on the landed gentries’ estates would, of course, have been illegal, and did nothing for the tarnished reputation of the Whippet – and as a breed, they were frowned upon. Also at this time, coursing with Greyhounds was highly popular, and also lucrative through betting, but was exclusively practised by those whom the poachers probably targeted.

Noted Belgian-born author, Alfred de Sauvenière, himself a landowner near to Paris, introduced coursing meets on his own land, establishing the sport in 1897. A prolific author, his book Les Courses de Lévriers (1899) is much sought after. He studied the lifestyle of English coal miners in the latter half of the nineteenth century, and discovered the origins of the sports that became synonymous with the Whippet. It is not surprising that as a result of de Sauvenière’s writings, it became generally accepted that the Whippet originated in the north-east of England. However, this type of rabbit courser was the combination of Greyhound blood with the addition of various breeds or types of terrier, or anything that would enhance their performance in the coursing field. It is thought that Collie was also introduced, and this is reflected in the ‘Faults’ section of the Whippet Breed Standard. In physique the Collie was strongly muscled and deep-chested, it was generally broken coated, and weighed about 9kg. These dogs would be best suited to the rigorous coursing and catching of live game, and were bred for stamina during a long course.

In around 1875 de Sauvenière also wrote about a fox terrier breeder, John Hammond. Hammond recognised the fine qualities of the ‘Greyhound of Italy’ that made it a shapely, streamlined runner. He crossed these dogs with his terriers, and produced a racing dog that became extremely successful. Not to be outdone, others quickly followed suit, and this crossbreeding began generations of increasingly whippet-like running dogs with an inbuilt tenacity drawn from the terrier. They were often known as ‘Hitalians’, and were mainly rough-haired or open-coated. Italian Greyhounds did seem to be a well-established breed in this country by this time, and so presented a useful outcross.

A Variety of Names

Despite being rarely mentioned in renowned books of the dog, where more popular breeds appear, Whippets seem only to be mentioned in descriptions of hunting – but under different names to the Whippet: Rabbit Courser, Tumbler, Rag dog, Snap dog. ‘Snap dog’ was possibly derived from the other mining areas where the breeds’ origin is less appealing. In effectively a course, live prey such as a rabbit was released in a fenced or walled area and the Snap dog gave chase; the dogs were usually used in pairs, and caught their prey with a ‘snap!’ However, a much more credible source, F.C. Hignett in The New Book of the Dog (1907), himself a Whippet ‘fancier’, said:

A Whippet is too fragile in his anatomy for fighting, so would ‘snap’ at his opponent with such celerity as to take by surprise even the most watchful, while the strength of his jaw, combined with its comparatively great length, enables him to inflict severe punishment at the first grab. It is owing to this habit, which is common to all Whippets, that they were originally known as Snap dogs.

It is also suggested that ‘Snap’ comes from the way in which the excited racing dogs snapped at one another, necessitating the development of the racing muzzle. John Caius in his Canibus Britannicus had already spoken of Whippets as ‘Tumblers’, which described the way a Whippet galloped at high speed: full of enthusiasm, stumbling and cartwheeling head over heels, and without breaking rhythm, carried on galloping. This is a trait well known today.

Racing Dogs

Early in the nineteenth century, miners and cotton industrial workers developed ‘racing dogs’. These racers were known in Cumbria, Lancashire, Yorkshire and as far south as Staffordshire and West Wales, where racing clubs sprang up as their popularity increased. The racers’ appearance indicated that they, too, were bred down from Greyhounds, though their physique was much different to those common in the North East. Firstly they were smooth coated, indicating that they were a purer descendant of the Greyhound, and of lighter build, averaging anything from 5kg up to 10kg. They were much finer and more streamlined in shape. This caused a sport to develop that involved racing the Whippet but without live game; it became very popular as coursing started to lose its appeal and was eventually pronounced illegal.

These racing dogs were of a definite type, because as the sport became more standardised so did the Whippet. The Whippet raced up a straight line of grass or cinder track, up to 150m long, being released at one end either by a handler or latterly from a ‘box’ or trap, and running towards their owners, who enticed them with treats or waved rags. This racer type was best suited to short, sharp, speed running, much needed to win races. Their appeal also generated an interest in those showgoers of other breeds. They became the foundation stock of the Whippet almost by default, specifically bought in by would-be breeders of the nineteenth century. As their popularity increased, so did those interested in establishing lines that are behind today’s show Whippets.

Nineteenth-century Staffordshire inkwells.

The Whippet in Art

There are many works of art, documents and artefacts which show that the Whippet ‘type’, at least, has been around for some time much earlier than the nineteenth century. Of course it is a breed enthusiast’s joy to grab any item where there is a breed likeness evident, and fortunately there is a large array to be had. But looking more into these treasures, the form of a smaller-sized Greyhound can be seen to have origins in other countries of Europe as well as England. A study of the Italian Greyhound by breed researcher Edith Hogel, led her to some of the mummified dogs in ancient Egypt. In a room of embalmed animals, she found a skeleton that showed a strong resemblance not only in shape but also in size to the Italian Greyhound. A larger mummified dog in The Museum of Egyptian Antiquities is of similar type and shape, but much larger in frame. So it is feasible that there could have been a similar dog in between these two in size.

Nineteenth-century English-made life-size bronzes.

Elsewhere, the famous ‘stone dog’ of Pompeii is quite Whippet-like in its pose, and in the Vatican Museum in Vatican City many sculptures show a Whippet-like hound. Around the time of the great Low Countries artists, Greyhound types were commonly roaming the streets and feature in many masterpieces.

In many works of art it is questionable as to whether the dog is a Whippet, an Italian Greyhound or a Greyhound. An undeniably close relationship between the three breeds necessitates a difference in ‘breed specific’ features being recognised, not only those that a breed specialist can recognise, but that are also recognisable to the public eye. This is problematic, as many of the dogs illustrated are not always to scale in relation to the surrounding features. One characteristic for sure is size, which can be estimated by comparison with perhaps his master or surrounding items contained in the work. But it remains that a single work of art can be claimed by a breed enthusiast to be of ‘one of theirs’, and many works are probably Italian Greyhounds or Greyhounds of varying sizes; however, we can adopt many as illustrating a Whippet.

As we progress into the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, a rise in popularity in the Whippet as a breed in its own right generated an interest with artists, who depicted subjects that are clearly Whippets although not titled as such. One painting of great interest to Whippet owners is the portrait of the first two Whippet male champions Zuber and Enterprise from 1892. Painted by William Eddowes Turner, it is owned in a private collection. Modern artists such as Whippet owner Lucien Freud often included Whippets in his paintings.

Whippets c.1939 by George Blessed, Pitmen Painter.

In the North East of England the famous Pitmen Painters were a group of miners who took up painting as part of the Workers’ Educational Association. The art class began on 29 October 1934 in Ashington YMCA hall, and one of its members, George Blessed, painted Whippets in 1939. It now hangs in the Woodhorn Mining Museum. Another artist from that area, Norman Cornish, whose work has become very popular since his death in 2014, highlights the working man’s view of the world and depicts many Whippets in his paintings.

Original ink drawing by Eugene Jacobs.

There are contemporary artists within the Whippet community such as Viv Rainsbury, Diana Webber and Bridget Lee, and it is not surprising that the elegance of the Whippet inspired them. The elegant form of the Whippet lends itself to be the model for sculptures, and many are available today in different media. Names such as Nymphenburg, Meissen, Minton and PJ Mene have modelled statues in porcelain, majolica and bronze, and there are many English models – for example Beswick’s model of Ch. Wingedfoot Marksman of Allways, and Border Fine Art’s first Whippet model of Falconcrag The Impressario.

Twentieth-century model signed PJ 1970.

Development of ‘The Modern Whippet’

In the North East the breed developed more slowly, with the rough-haired variety being more popular – a crossbred rough-haired working dog that includes Whippet blood can be seen even today. A popular and traditional cross is with the Bedlington Terrier. The rougher-haired Whippet would be more suited to the harsher northern weather as it was probably hardier. As racing gained popularity owners began to shave their dogs, and eventually the smooth-haired predominated.

Early in the nineteenth century, Scottish curator, naturalist and editor Thomas Brown wrote: ‘Victorian English writers describe emerging, the modern breed of Whippet or Snap dog, bred for catching rabbits, coursing competitions, straight rag racing and for the novel show fancy.’ This is a sudden development, and recognition of the breed as ‘the modern Whippet’. Does this intimate that the breed has been elevated from its disreputable past to one of character and type, and become more stylised? The Victorians had a flair for designing many of our present-day breeds, and the Whippet was no exception. For the Whippet to emerge as a show dog as early as the mid-nineteenth century and hold a ‘type’ must surely support the theory that many communities were breeding to produce a ‘breed’, and one that was able to fulfil its function and conform to ‘standards’ – and indeed this would also infer that they had a purity of blood, presumably being bred down from Greyhounds.

One influential Whippet owner, the Duchess of Newcastle, gave Whippets a boost and established the breed within a higher profile. Kathleen, Duchess of Newcastle, lived at Clumber Park in Nottingham and was renowned for her ‘of Notts’ kennel. She was a leading breeder and respected judge of Clumber Spaniels, Borzois, Smooth and Wire-Haired Fox Terriers, Deerhounds and Whippets. She would probably have been instrumental in drafting Herbert Vickers’ letter requesting the recognition of The Whippet Club to The Kennel Club in 1899. Herbert Vickers, the owner of the first Whippet Champion, Zuber, worked as a building contractor along with his father in and around Clumber Park, and this was the address given on his letter to The Kennel Club.

In F.C. Hignett’s account of the breed in The New Book of the Dog (1907) he says:

It does not follow that the best-looking Whippet is the best racer, otherwise many of the champion show dogs would never have seen a judging ring in a show, for the majority of them have been disposed of by their breeders because they were not quite fleet of foot enough to win races.

The racing community’s loss was certainly the show world’s gain. These cast-offs formed the basis on which the modern-day Whippet was built, and many of them continue the legacy and compete successfully at race meetings, as well as being show Whippets.

A.H. Opie judging Best Bitch at Crufts in 1951. Second from right, Ch. Shirleymoor Set Fair, who was Best of Breed.

The Whippet Club was one of the first breed clubs to be registered with The Kennel Club in 1899. The first President was J.R. Fothergill, a Whippeteer, himself recorded as winning Best of Breed at Crufts in 1902 with Trylen Mystery. Early founder officers and committee were B.S. Fitter (secretary); Albert Lamotte of the Shirley kennel; Fred Bottomley, one of the Manorley owners; Lady Arthur Grosvenor, owner of some Ladiesfield Whippets; M. Harding Cox, a member of The Kennel Club; A.H. Opie, a popular judge; W.L. Beara of the Willes’ kennel; and J.E. Barker, the first of the Barmaud dynasty. All were influential, playing a part as breeders, exhibitors and judges in the early part of the club’s and breed’s history, and firmly establishing the breed.

In Herbert Compton’s book Twentieth Century Dogs, published in 1902, quotes are included from the leading Whippet breeders of the time; they are reproduced here:

… it is pretty certain that the Whippet Club – which now has such names on its front page as Mr J.R. Fothergill, Lady Arthur Grosvenor, Mr Fred Bottomley, Mr Harding Cox, and Mr A. Lamotte – will soon improve the status of the breed, and carry it into the position which the intrinsic merits and physical beauties of the little animal it has been founded to foster, right worthily deserve. The sport of whippet racing suitably conducted is one in which ladies might find a great delight; it offers the quintessence of excitement, crystallised into a few seconds; it is capable of being conducted within private enclosures and kept select, and it adds an attraction to dog-keeping which is not to be obtained in any other breed under the same innocent conditions. There is no blood shed, and there is lots of fun, and, I doubt not, as much joy in owning a winner as in the proprietorship of other ‘fleetest of their kind’. And for this reason alone the development of whippet-racing is a consummation which no one could object to.

The following are the notes I have received from my contributors in this section:

Mr J.R. Fothergill (President of The Whippet Club): Nothing could be better as regards type, than many of the bitches now being shown, but the breed requires a few good dogs, a few good breeders, and a few good supporters. The values of the points seem to me good, but in judging by points one can often go wide of the mark. More especially is this the case with whippets and greyhounds. With these dogs individual points are of little importance, even if they have them all in equal perfection, without symmetry, balance and simplicity of construction. The whippet is intended for running only. Many a dog, with a row of bad points, is faster and handier than many a good showing dog. The reason is that they have the above-mentioned qualities. Judge a whippet out of focus first and then adjust your sight for detail.

I like a whippet first as a race dog, a more interesting study for the subject of animal psychology is hard to find, but there is no need to expatiate upon this somewhat abstract subject here. Like all dogs, their characters are like those of their masters, and they are as easily impressionable, and taught, as any other dog I have had to do with. A thorough bred whippet can be taught retrieving and ratting, whilst he is naturally a better hand at rabbits than a terrier or a greyhound. I have four thorough bred whippets that will hunt the scent of a rabbit or any other scent for any distance. Each takes its own line and they are remarkably clever at casting and travel at a great speed. I have known them to hunt a hare entirely by its scent over the Downs for about a mile and a half. A lady looks better with a whippet than with most other dogs, they are so ornamental. Though if for this purpose a foil is required, a bulldog certainly serves best.

Mr Harding Cox: There is not much fault to find with the type of the breed as it exists today, but breeders must keep up sufficient bone, and must be careful about close, strong, well arched, and well split up feet. I have always judged whippets on greyhound lines, making due allowance for difference of type in hindquarters. Beyond the sport afforded by whippets in sprinting matches and coursing rabbits, I fancy there is little to recommend them as companions, though they are lively and amiable as a rule.

Mrs Charles Chapman: I think there is a danger in breeding whippets fit for the bench only and losing sight of the qualities necessary for racing. The whippet is gifted with extraordinary speed, and for the limited distance it races exceeds that of the greyhound. My bitch Ch Rosette of Radnage accomplished the feat of winning a championship at the Kennel Club Show of 1900, and winning the handicap promoted by the Whippet Club at the same show. Whippet racing, properly conducted, is a most charming sport and essentially suitable for ladies to interest themselves in, and I feel very sorry that the efforts made to popularise it seem to have been without result. Whippets, or more properly speaking race dogs, are capital house companions but their principal interest lies in the sport they afford.

And for my ideal whippet, I see him held in the leash by his handler eager for the start. He is straining every nerve, quivering with excitement and fairly screaming in his anxiety to be after the white rag, to reach which is to the uninitiated the inexplicable cause of this mysterious racing. My ideal is of brindle colour, about 15 or 16 Ibs in weight, so that he is well placed in the handicap. His head is long and lean, his mouth perfectly level, his ears small, and shoulders as sloping as possible. His body is well tucked up, with the brisket very deep, his back slightly arched, with a whip tail carried low but nicely curved. His hindquarters are very muscular, and his fore legs absolutely straight, with feet hard and close, and hind legs well turned with hocks bent under him, all the muscles induced by the thorough training he has undergone showing – he looks what he is – a perfect picture of a ‘race dog’.

Mr A. Lamotte: The breed is making great strides in the right direction, viz a greyhound weighing about 20 Ibs. In the Standard of Points, great value should be laid on power in hindquarters and loin, good feet and legs, deep brisket with plenty of heart room. The whippet was made to race and gallop short distances at a great speed. To see these small pets fighting it out yard by yard on the track is wonderful. And how they love the sport. Unfortunate it is that it is not in better hands, but we must hope that this will improve in time. The whippet as a pet is a very charming animal, and its affection for its owner is great. Watching them running about with their quick graceful movements is a joy to the eye.

Mr Fred Bottomley: The type of whippet today is better than of late, though there is still room for improvement in shoulders, weak pasterns, straight hocks, and size, which in my opinion should not exceed 20 Ibs. I am the oldest whippet exhibitor, and for the last ten years have made but few additions to my kennels, always showing my own strain which include Ch Manorley New Boy and Ch Manorley Model, now withdrawn from the show bench. I have always found whippets the best of pals, very game dogs, and the fastest dog living for their size.

This is strong confirmation from the foremost leaders of the breed that the Whippet is firmly established and going from strength to strength. We will probably never know exactly the true origins of the Whippet, but we should be appreciative of these pioneers who clearly had the talent and stockmanship that built such a foundation for the breed that is now one of the most popular.

CHAPTER 2

Early Foundation and Influential Breeders

G.H. Nutt

In the 1893 edition of the Crufts catalogue, George H. Nutt of Pulborough, in Sussex, was recorded as exhibiting five dogs under the heading ‘Whippets’. Four of them, entered as ‘Pulboro’ Tommy, Bluey, Bob and Brindle, were listed as Greyhound/Whippets, while ‘Pulboro’ Bessy was a Bedlington/Whippet. So it appears that quite a variation would have been present in those early days under the breed heading ‘Whippets’, and accepted as such. Nutt was well known, distinguished in appearance and very popular with everyone. He raced his dogs as well as showing them, and was famously known for travelling to the Scheveningen show in Holland in the late 1890s with a string of six Whippets. One account of his expedition related that he delighted the dog show people and the Burgomaster with his racing dogs, demonstrating the keenness of Whippets racing – although this was not without its mishaps. He went on to sell many racing Whippets to the Netherlands. George Nutt was also the secretary and show manager of one of the first dog shows at Crystal Palace in June 1870.

Herbert Vickers