6,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

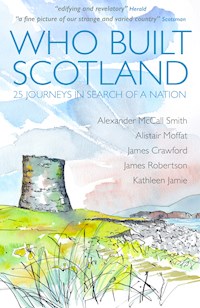

- Herausgeber: Historic Environment Scotland

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

‘a fine picture of our strange and varied country’ Scotsman

‘edifying and revelatory’ Herald

‘an epic love story to Scotland’ Courier

‘by turns inspiring and fascinating … a book that gives context to the Scotland we see around us today’ Undiscovered Scotland

‘a fascinating alternative take on the country’s social, political and cultural histories’ Scottish Field *****

Kathleen Jamie, Alexander McCall Smith, Alistair Moffat, James Robertson and James Crawford travel across the country to tell the story of the nation, from abandoned islands and lonely glens to the heart of our modern cities. Whether visiting Shetland’s Mousa Broch at midsummer, following in the footsteps of pilgrims to Iona Abbey, joining the tourist bustle at Edinburgh Castle, scaling the Forth Bridge or staying in an off-the-grid eco-bothy, the authors unravel the stories of the places, people and passions that have had an enduring impact on the landscape and character of Scotland.

Alexander McCall Smith is the author of over 80 books, including

the world-famous No. 1 Ladies’ Detective Agency series and the

Scotland Street novels.

Alistair Moffat is an award-winning author of history books including Scotland: A History from Earliest Times and The Great Tapestry of Scotland.

James Crawford is the Saltire-nominated author of Fallen Glory and the presenter of the landmark BBC TV series Scotland from the Sky.

James Robertson is the Booker-longlisted author of highly acclaimed novels including And the Land Lay Still, Joseph Knight and The Testament of Gideon Mack.

Kathleen Jamie is a Saltire and Costa-winning writer of poetry and non-fiction, including The Bonniest Companie and the critically acclaimed essay collections Sightlines and Findings.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 567

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Ähnliche

Who Built Scotland

Alexander McCall Smith

Alistair Moffat

James Crawford

James Robertson

Kathleen Jamie

Published in 2017 by Historic Environment Scotland Enterprises Limited SC510997

Historic Environment Scotland

Longmore House

Salisbury Place

Edinburgh EH9 1SH

Registered Charity SC045925

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data. A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

eISBN 978 1 84917 245 5

Individual chapters remain the copyright of their respective authors:

Alexander McCall Smith, Alistair Moffat, James Crawford, James Robertson and Kathleen Jamie

© Historic Environment Scotland 2017 Unless otherwise stated all image copyright is managed by Historic Environment Scotland

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the prior written permission of Historic Environment Scotland. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution.

Cover painting by Oliver Brookes

Proofread by Mairi Sutherland

Supported by Creative Scotland

Contents

1

Signs and Traces

Kathleen Jamie

Geldie Burn, 800 BC

2

The Sky Temple

Alistair Moffat

Cairnpapple Hill, West Lothian, 3500 BC

3

Who are You, and What do You Think You’re Looking at

James Robertson

Calanais, Isle of Lewis, 3000 BC

4

The Stone Mother

Kathleen Jamie

Mousa Broch, 100 BC

5

They Came in a Small Boat

Alexander McCall Smith

Iona Abbey, AD 563

6

The Masons’ Marks

Kathleen Jamie

Glasgow Cathedral, AD 600s

7

Rock of Ages

Alistair Moffat

Edinburgh Castle, 1100s

8

Cool Scotia

James Crawford

The Great Hall, Stirling Castle, 1503

9

Never-Failing Springs in the Desert

James Robertson

Innerpeffray Library, 1600s

10

The Lost Estate

James Crawford

Mavisbank House, 1723

11

Kirks Without People

James Robertson

Auld Alloway Kirk, 1791

12

The Making of a Classical Gem

Alexander McCall Smith

Charlotte Square, Edinburgh, 1791–1820

13

The Fire of the Dram

Alistair Moffat

Glenlivet Distillery, 1800s

14

On This Rock

Alexander McCall Smith

Bell Rock Lighthouse, 1807

15

Nothing Like My Ain House

James Robertson

Abbotsford, 1811

16

Surgery’s Temple

Alexander McCall Smith

Surgeons’ Hall, 1830s

17

The Greatest Wonder of the Century

James Robertson

The Forth Bridge, 1881

18

A Little Girl Remembers

Alistair Moffat

Glasgow School of Art, 1896–1909

19

The Bewteis of the Futeball

James Crawford

Hampden Park, Glasgow, 1903

20

Far From Home

Alexander McCall Smith

The Italian Chapel, 1940s

21

Arcadia

Alistair Moffat

Inchmyre Prefabs, Kelso, 1948

22

Views and Vision

Kathleen Jamie

Anniesland Court, 1968

23

Homecoming

James Crawford

Sullom Voe, Shetland, 1974

24

Caring for the Carers

Kathleen Jamie

Maggie’s Centre, Fife 2006

25

A View with a Room

James Crawford

Sweeney’s Bothy, Eigg 2014

Introduction

Look around you, wherever you are right now. Maybe you are reading this while browsing in a bookshop in a city; or you are on a bus or train rumbling through a town centre; or you are in an armchair in a tenement flat or a semi-detached house or a cottage out on its own, surrounded by nothing but fields and stone dykes. Stop for a moment, and take in all the things you can see. There may be roads and pavements, long lines of concrete and tarmac filled with cars and pedestrians. There may be streetlights, shining down on row after row of houses, stretching off into a suburban distance. Perhaps you are in a hotel, ten storeys high, with a view that takes in a whole city, other buildings far below, thinning out towards hills and a river that widens to the sea. Maybe you are in a village on the coast – an old village with a hook of stone harbour and, beyond, out on a promontory, a tall, whitewashed tower with a spinning light, standing alone. Or you are high in the mountains, far away from any urban hum, in a basic, tin-roofed stone bothy for climbers and walkers, reading by the light of a fire you’ve lit yourself among the ashes of a soot-blackened hearth.

Now think – someone, at some time, built all of this. A process was started, long ago, to put things into, and on top of, the land. Permanent things. Things that might, and in many cases have, lasted far beyond the lives of their makers. In simplest terms, at some point, we stopped being just travellers, and we became builders. The fires we made to keep us warm no longer moved from place to place. We put walls around them and roofs over them. We made homes. Places for families – places to eat, work, sleep, love, fight and argue. Places to live.

You can still see some of these places today. Travel to Orkney then catch a ferry – or if you’re brave, a ten-seater twin-prop plane – to the northernmost island, Papa Westray, and then head on to a place on the west coast called the Knap of Howar. There, fringed with grass and wildflowers and directly overlooking the sea, are two holes in the ground. From above, seen side-by-side, they look like two footprints: two footprints that were hidden beneath the earth until a storm in the 1930s tore at the sand and soil and exposed the tops of walls made of interlocking stone. Now you can climb down to the shore side, stoop low to pass through a doorway. It is a journey of just a few metres, but also of 5,000 years. You are inside the oldest building still standing in northern Europe. You are sheltered from the wind, but it still whips the air above you, in the empty space that once held a roof. The entry doorway frames perfectly the shore, sea and sky. The sun sets on that horizon. There is a fireplace and the remains of ancient furniture and cupboards. And as you stand there, you realise that it is not so much distance that you feel from the people who built these homes – who lived in them for generation after generation – as intimacy. Our modern living rooms and kitchens, with sofas and smart TVs and electric ovens and microwaves, aren’t really so different. You can pull on the thread between now and then and feel it taut and strong.

What we build always reveals things that are deeply and innately human. Because all buildings are stories, one way or another. They each offer their own threads to pull, threads that lead you to ideas, emotions, hopes, dreams, fears and conceits. So go on, look at everything around you and think, really think, about how it got there. Who planned it, who designed it, who paid for it, who actually got their hands dirty making it? Who lived in it, or worked in it, or worshipped in it, or learnt in it, or was born in it, or died in it? It’s a dizzying prospect, vertigo-inducing even, when you attempt to peer over the metaphorical parapet at the layers of history upon which all of our lives are built.

In this book, we have picked just twenty-five buildings to take us from a beginning to an (open) end. As a result, we will, inevitably, have missed both the obvious and the obscure. But it is the nature of the journey that is important. Starting with the earliest hearths left behind by our nameless ancestors, we will move steadily forward, and in the process tell a new history of Scotland, rooted in the roots themselves, the things that we have raised up – in stone, wood, steel, glass and concrete – and that still persist in the landscape, whether hunkered down with unshakable tenacity, or reduced to the faintest of traces. Our five authors have been all across the county in the process, from city centres to remote glens and lonely island peninsulas. They have travelled to these buildings and – where they have been able – walked inside them or through them or on top of them, to reflect on both their histories and how they relate to personal stories and experiences. This book, then, is an account of twenty-five individual journeys, which come together to form a narrative of a nation. But it is also an invitation to you, the reader, to get out and explore Scotland, to look anew at everything that you see, to reach out to the stones and feel them coarse or smooth to the touch and to find the seam that leads you onwards, on your own journey.

1

Signs and Traces

Kathleen Jamie

Geldie Burn, 8000 BC

In the beginning was a hearth, a gathering round the fire.

In the beginning was shelter, hides stretched over wood, with water nearby.

In the beginning was the land, not long emerged from the ice, seashores, rivers, glens and watersheds. Birch and hazel woods, the open hill.

In the beginning was the smell of fish roasting in the cinders, of hazelnuts.

Nowadays, if you make your way to Braemar, and then to the Linn of Dee, it’s possible to park a car there under the Scots pines, and walk or cycle farther into the Mar Lodge Estate, following the upper Dee by a Land Rover track through its broad strath up to White Bridge, where the Dee and the Geldie meet.

Back then, 8,000 years ago, you lived with stone and wood. With animals, birds and fish. With the seasons and the weather, with one another. You moved around the country: a season here, a gathering there. Some places were familiar; you came over and again, took what you needed. Intimately your hands knew wood, stone, bone, hide, gut, grass, bark, sinew, antler.

The bridge crosses the Dee, which would otherwise be dangerous in spate. You pass remnants of native pine wood and more modern plantations; a few ruined blackhouses. Signs direct you toward the high passes, the fabled names of the Cairngorms: the Lairig Ghru. The hills are almost free of snow. The sky is high and clear; today, white clouds are travelling eastward.

It wasn’t enough to say ‘bone’. Which bone? Scapula or knuckle? Which species of animal, at what age? Likewise grass. What kind was best for weaving hoods, which for fish baskets?

You knew these things. You knew things we’d still recognise now, in our hearts: the smell of wood smoke, faces by firelight. The stars at night. The turning seasons. A coming and going. Voices. Tasks to be done.

A day in early summer then was just as long and as full of bright promise.

At Chest of Dee you can follow that river higher toward its source. There is a narrow part where the water, blue and aquamarine, surges between rocks so strongly it purls backward on itself. A place of recreation and solitude, haunt of the long-distance hillwalker and naturalist.

Potentially dangerous. The hills stand guard. In the clear meltwater of the pool at the waterfall, a single fish inhabits its own world.

At the confluence of two rivers, on a flat shingly riverbank. The water is fast and clear – almost greenish. It’s meltwater falling through a tight linn, draining the snowfields higher in the mountains. Perhaps there are sparse stands of birch, hazel, even pine to feed the fires. There is a camp. Tents of hide, windbreaks of woven willow. Morning smoke. Voices. Work to be done. Around the tents are drying racks for fish or meat, frames to stretch skins.

When you arrived there were the traces of the last time you were here – bits of stone, a midden, dark ashy patches where the fires were lit – a familiarity. You’re here for a reason, following something maybe, a herd of animals that gather at this time of year. Or a certain wood, or a certain kind of stone. You have followed a river well inland, almost to its source.

The river which meets the Dee here is the Geldie. ‘Geldie’ is an old name meaning clear, white, pure. The track follows the river as the Geldie trends eastward. Today, 25 blackcock were gathered at their lek, an adder basked on the path where the Bynack Burn joined the Geldie.

The path rises onto heather, then narrows to a walking trail.

The river is below on your left, meandering and looping because the little strath is level; the hills on the south side are even, glaciated, heather covered. There are no trees whatsoever. On the opposite bank stand the ruins of Geldie Lodge, a nineteenth century shooting lodge; a brief intervention in the landscape, in the long scheme of things.

You know fine well that if you follow one of the rivers, it will take you higher into the hills. You were first taken there as a youngster – it was an adventure. After some hours’ walk you will turn westward into a higher, lightly wooded valley, with a marshy floor. Perhaps there are deer up there, grazing quietly, maybe even reindeer on the high slopes. Perhaps the reindeer are already gone, they have become a story the elders tell.

However, you’ve left the main camp by the waterfall and crossed the major river. Alone, or in a small gang. You follow the lesser river, keeping to its northern bank and head into the hills. There’s a place you favour upstream, a good morning’s walk away, where you reckon you’ll stop for the night. Though it’s on a small ridge, it’s sheltered among spare trees. The valley it looks out upon is sedgy, with sparse birch and hazel trees. The gentle hills are green.

It was here, at about 1,500 feet, where the path crosses Caonachan Ruadha (the wee red burn) that some workers repairing the eroding footpath discovered under the peat a number of tiny flint artefacts. They saw them with a sharp eye; a hunter-gatherer’s eye.

The flints comprised what the archaeologists call a ‘lithic scatter’. Tiny blades, not the length of your thumbnail, flakes and off-cuts of flint and rhyolite. They lay strewn in such a way that suggested they had littered the ground around a fire within a tent of some kind. A small camp, no more than two or three people on a high route through the hills, among trees, perhaps for some special function. That was before the peat came and covered them.

Another half day’s march would take you to the top of the glen. The hills, still snow-wreathed, appear to close the glen but you know there are routes between them. If you kept walking and managed some tricky river crossings, you’d find your way down into another separate river system, a whole different part of the country, maybe another kind of people. But tonight you stop.

What have you brought? You’ve brought some means of making fire. Hides to sleep under. Tools, knives to cut a few withies. A pouchful of nuts, pemmican of some sort. Some twigs of yew – why that? For its cleansing smoke, for tipping poison darts? Snares, which you’ll set. The pelt of a hare, still in its winter whites, makes perfect mittens, baby clothes. Perhaps bow and arrows, perhaps you’re waiting for migrating animals to file through the high pass.

You set the fire. Do you need to consider bears? To keep someone awake on bear-watch at night? Maybe you’ll see prints in the marshy mud but they won’t worry you.

The scatter of flints, a fire-scorched place, the site of what was likely a shelter. Little else is preserved in Scotland’s somewhat acidic soil. The carbon dating of the hearth gave dates of 8,000 years ago; suggesting the mountains were part of people’s range and resource from the earliest days of human settlement.

Why were they here?

At this time of year the nights are short but cold. Actually, they’re getting colder. The elders say winters are much colder than they used to be, snow and ice are lingering longer into the year. You relish the daylight, having come through a winter lit mainly by moon and firelight, or lamps of animal fat. Here in the high glen, you use the gift of daylight. You sit on stones in the gloaming by the fire re-sharpening and re-working tools: the tiny blades and flint points which are an endless labour if they are to keep their edge. A stone in either hand, you knap carefully. The chipped-off pieces lie where they fall. The flint has come with you from the coast, but there are rhyolite outcrops up here. Perhaps you’ll fetch some while you’re about it. Yours are working hands: muscular, knowledgeable.

You feed the fire. When you talk, you talk about what you’re doing, about each other, about weather-signs, animal-signs. Some daft adventure you recall. A story.

What do you call this place? Where did you say you were going when you set off, and why? Who might you meet up here, on the high track through the mountains?

There are Mesolithic sites all along the Dee, only now being discovered. At Chest of Dee, there were bigger sites, possibly longer lasting, repeatedly visited, with their hearths and lithic scatters. It may be that this little camp at Caochanan Ruadha is an outpost of those. You can sit here now under a bright sky and look westward up to where the river rises.

You might meet a lone walker passing, with his backpack, a portable shelter, some warm well-made clothes, some easy-to-carry food. When he speaks, you can tell where he comes from. He describes crossing a river, dangerously, water up to his waist. You exchange pleasantries, he walks on.

Your shadows are long as you walk away from camp to check your snares before the ravens get there first. The sky is clear, ashy pink in the west, a quarter moon already risen high. It all bodes well for the morrow, and the morrow. You lived lightly on the land for 4,000 years.

Imagine! Four thousand spring times. A million and a half days and nights. What did they build, our hunter-gatherer forebears? Nothing as yet discovered, if by ‘build’ you mean stone piled on stone. Our forebears left little trace of themselves before the transition to farming was complete. But they built a long culture, a profound knowledge communicated by memory, story, instruction by elders to youngsters.

Wind in the grasses. River-rush. Sun on your face. Silence on the hills.

Westward, the wide glen closed by hills against a high spring sky.

*

Then came farms, beasts, crops. A few black kye grazing, a few fields of barley or bere. Still the hearth, peat-burning now though, that sweetest smoke. The year still turns, but it’s the farming year, a pastoral year.

On a midsummer’s afternoon in the upper reaches of a Perthshire glen, up where the burn rises, where no-one lives and few folk linger, you’re exploring a cluster of ruins. Even the word ‘ruin’ sounds too grand for these traces of stone and turf.

You’re quite alone, though it’s a fine day to be outdoors and the Ben Lawers car park is full. Folk have other reasons nowadays for heading to the hills. On the summit of Ben Lawers itself – a well-worn path leads there – a gang of youngsters are trying to launch a paraglider.

If they weren’t given on the OS map you might hardly notice the ruins, they are so of a piece with the landscape: same stone, same turf and moss. But if you sit for a few minutes, getting your eye in, you can detect more and more. They’re on either side of the burn, raised up on small green knolls and ridges, each within hailing distance of the next.

You creep out under the low lintel into the morning, glance at the hillsides, the sky. Perhaps cloud has lowered during the night to hide the surrounding summits; a shower dampened the turf roofs and grasses underfoot. A wee shower doesn’t matter, the bothans are newly repaired.

Peat smoke from a dozen other huts is drifting over the upper glen. Peat smoke and dung: smells so familiar you don’t notice them. You smell of peat smoke yourself, your clothes and hair. Later, when the sun breaks through to warm the ground, you’ll catch the scent of grasses and wildflowers too.

Some are drystane enclosures with walls just knee high, others are turf, mossy and overgrown. One or two are ovals with a narrow doorway on the long side you can squeeze through. You can sit inside a little stone hut, open to the sky. Reeds and grasses now grow where people once slept. Sheep enter now too; tufts of fleece are caught on the stones. The huts seem too small inside, taking up no more ground than tents, with barely room to lie your length, never mind space for children, a fire, chattels. One or two of the huts still have a stone recess set into their end wall, a cool place to stand cheeses.

The cattle are lowing, the calves answer. Aye, better get them milked so the herds can drive them up to the day’s pasture. The sheep and goats are on the steeper braes, with a few herds to guard them against foxes – or wolves, even, in the olden days. And to keep them on your lands. Or your laird’s lands, rather.

The sky is high and blue. It’s mid-June and the whole upper glen is silent but for pipits, and the Allt Gleann Da-Eig hastening down to join the River Lyon. There is not a human voice, not a cow or calf, but the grass still remembers to be green after all these years, enclosed and protected by the higher hills.

There are 6,200 recorded shieling sites in Scotland, reaching from Perthshire north and west to the Western Isles. An entire pastoral culture, thousands of years’ worth, expressed gently in the high hills and moors, and little visited today.

Huts and shelters, cattle pens, dairies, stores. Generations of re-building and repair on the same green knoll.

Your neighbour’s calling from her door; aye, it promises to be a fine day. At your own door, your goods and gear brought up from the wintertown: your churn and milk pails, maybe a spinning wheel or a distaff. There’s never not work to do. You must take advantage of the long light, winter will come soon enough – darkness and firelight. But for now the season is still young. You go to the burn for water. There are bannocks to bake, the bairns need their breakfast, there’s the kye to tend to, your daughter will help. You always lived with cattle. You know their ways, their needs and ailments and cures. How to milk and churn, how to make butter, how to keep cheese. You learned from your mother, she from her mother.

Who came to the shielings? Accounts vary. Fond tradition says only the women and bairns stayed for the full six weeks or so in the hills, the menfolk had work with the ripening crops below. Some sources speak of a grand procession up from the glen as entire townships made the move. Others suggest that latterly it was just the milkmaids and herds. Whatever, the annual flit to summer grazings had been happening since time out of mind. It was the custom in medieval times, for sure. Maybe its origins are much older, reaching back to the Bronze Age, even the Neolithic, when people began keeping livestock and growing crops. These are long eras of time and so not without changes. There were changes of society and politics, of land control and ownership. Populations waxed and waned. There were serious fluctuations in climate: the balmy medieval era gave way to sharp fourteenth century cooling, with associated plague. After a brief recovery came the Little Ice Age, a time of dearth.

But the shielings! Places of high days and holidays, a sense of summer freedom for women and children. The shieling of poetry and song. It’s a romantic notion maybe, but why not? There is no contesting that the midsummer days were long in the north, then as now. Midsummer nights in the hills are but a few hours of cold blue before the day dawns again. Gloamings are long, the wildflowers bloom. One could gather tormentil (good for dysentery and even sunburn) and butterwort (considered a magic plant, offering protection from malevolent fairies).

You can send the bairns to pick flowers or roots, or fresh heather for your beds or the calves’ beds, or lichen for dyes, maybe a handful of early cloudberries.

If days were warm, there were surely long moments of peace and ease. But then as now, hours must have been spent huddled out of the rain. So much is constant: if you live by the land in marginal places, you must grasp what the land offers, and in Highland glens it offers a few fleeting weeks of high grazing. Bringing the milch cattle up into the hills allowed the lower grazings to recuperate, and kept hooves away from tender crops.

But you can’t see right down to the wintertown, because the glen turns east. For a few weeks, you are out of sight of your home. Though the days are long, they are fleeting, mind; soon the smell in the air changes, the nights darken, the mornings are cool. Harvest time is coming and needs you with the kye and the hens and the new-made cheeses and the bairns taller than when they left. Someone’s belly swelling, ready for a winter birth.

Though there are old island folk who still recall being carried to the shielings as infants, for the most part the practice was over by about 1800, and for the usual reasons: sheep, potatoes, agricultural improvement and associated depopulation, clearance. The new mills and mines of the Lowlands were opening their doors. So we have these innumerable small buildings left quietly on the land: marks of the common folk, female folk, of long custom. One can barely even call them ‘buildings’, just a few courses of stone or turf. They are not statements, they are not possessive – that’s their charm. They are cultural expressions, much as pipe music is. (Bagpipes are a pastoralist’s instrument, the bag was originally sheep’s or goat’s stomach.) At 1,500 or 1,600 feet, halfway between the valley floor and the summits, halfway between the modern cafes and hotels, and today’s windblown hillwalkers, a shieling ground carries a particular atmosphere. You can visit from one wee hut to the next, wondering who last slept there.

You sense a link to the land, though it was often a precarious and poor life. A link also to languages and music and implements and lore, to people’s knowledge, their ailments and ignorances. Rightly or wrongly, shieling grounds don’t speak of people torn violently from the land, but rather of the land relinquishing them, as easily as it surrenders the down of bog cotton, and – almost – awaiting their return. Mica sparkles in the hand-shifted stones, cloud-shadows pass on the hillsides. Because they were places for women and children and culture and memory, the hills are the better for the shielings.

But, for now, the sun’s burning off the low cloud, and breaks through. Though there still are wreaths of snow in the high corries. You feel the heat on your face and forearms. It may be summer, but there’s plenty work to be done, in the heat and sweat. There’s aye work, food to win, wool to spin to weave cloth to hide your nakedness and ever the rent to be found.

*

Industrial Revolution. Capitalism. Landowners realising there were fortunes to be made from rough stuff under their moors and hills. Almost all you needed was labour – lots of it. And people were fleeing the land, or thrown from it, or seeking wider horizons than their native glen.

You came up when you married and became a collier’s wife. A pitheadman’s wife. You were both 25, and it wasn’t long till the first baby arrived. The neighbours were kind, and there was no shortage of them: 400 folk crammed into a couple of squares and a few rows of houses the mine owners built.

An Ayrshire moor, on a summer’s day. On the western edge of the moors above Auchinleck, at 700 feet or so. Not high, but the sense is of space and openness. You’re on top of a mound that adds another 150 feet or so, and that makes all the difference. Eastward lies Airds Moss: eight miles of blanket bog, a place for birds – or it will be once the restorative work is complete.

South, the land rises again. There are still opencast mines there, trucks moving. A parade of lorries on the A70 between Muirkirk and Cumnock seems silent from up here. Westward, through, that’s where the real views open out. The land falls to the coast, there’s Arran. Goat Fell – in fact the whole lower Clyde. Is that Jura?

But the hill which offers this panorama is not natural. It’s an old bing; the spoil from an opencast site abandoned now. At first there were pits, and after the pits were worked out, the opencast mining began. The opencast site is a cruel-looking gouge in the earth, now deeply flooded, because opencast mining also came to an end. All mining up here ended. In the space of a long century it was over and done. Rapid industrialisation, unleashed capitalism – just a flash in the pan.

Not for those who spent entire lives up here, perhaps. It must have seemed eternal.

Your mother and in-laws aren’t far away. They were the ones who had come over from Ireland. From County Antrim farms to a mine. They still kept their accents. Down the row Scots names alternate with Irish: Moffat, Gormauley, McCarthy, Baxter, Stirling, Lafferty, Gemmel, Muir, McSherrie. All crammed in two rooms per family, one window. The young leaving their famished land in droves and considering themselves lucky, perhaps, to be hired.

North of the bing and the flooded opencast site stands one farmhouse, Darnconner, that looks as though it has endured since before the mining began, a link to the long centuries of farming that came before.

The bing is slowly earthing over. There are even butterflies feeding on flowers that like its dry stony ground.

Immediately north of the bing, a new wood is planted, Duncan’s Wood. The young trees, native species, are still in their protective tubes.

You’re no stranger to work, mind. Before you married you were in the cotton mills at Catrine, with your own meagre wage, but a wage. Now it’s a job of work to keep the place decent, and the family fed and clean from coal dust and glaur. Make and mend, redd the men’s clothes, bring water from the standpipe, keep the fire on. The moor’s at the door, near enough. No pavements. An endless job, especially in the winter rain. And the weans: five in all, eventually, evenly spread out over fifteen years. Not bad. But you didn’t live to see them grow. The firstborn was destined for the pit from the moment he was born. Wee Agnes was only five when you died. Your man James succumbed in 1917, to lung disease and heart disease.

You didn’t live to see your firstborn going off to the war; you were spared that worry, at least. He lived, married a kind lassie from the Borders, had a family of seven of his own. The war was his great adventure. After that, he was a miner all his days.

You can stand on the bing and see land, but not as hunter-gatherers or pastoralists would know, to be returned to over and over in a cycle. Life here was brief, brutal and extractive. Hire labour on the cheap, and when its over, its over. Move on. ‘There are no washing-houses, but several washing-house boilers have been erected. Whoever erected them forgot to build a house over them, and the women have to do their washing in the open air. There are two closets, without doors, for these seventeen families; and an open ashpit in the centre of the square was filled to overflowing and the stinking refuse strewn about for yards.’ So said the report by the new National Union of Mineworkers.

It’ll take an archaeologist’s eye to see the shapes in the land that were railbeds and pithead works and the footings of what were houses. They were cleared, not worth saving. Homes of all those miners and their wives and families lie tangled with the roots of the young trees.

As with the Mesolithic camps, as with the Highland shielings; they are almost invisible traces of people’s lives. Especially women’s. In this case, a few generations doing their best to defeat the squalor of the ‘raws’ the mining companies provided.

There must have been more to it than just cooking and cleaning, mustn’t there? More than glaur and dirt? Long summer evenings when the moor maybe wasn’t too bad a place; trains and carts to take you visiting, into Ayr or even Glasgow – surely. More to life than coal, and the winning of coal. Mining places were famous for their societies, the choirs and bands, philosophical and political societies, the hobbies and associations. But maybe just for the men.

You looked after the men and the men houked the coal and the coal fired the trains and ships and factories. You built the country, though no-one ever said as much.

In years to come, if the flooded opencast pit becomes a loch, you will have a natural landscape. The young trees will maybe make a forest eventually, though there is more to a wood than the trees. You need your microbes and fungus, flowers and understorey; the insects and birds all have to establish themselves. But give it 8,000 years or so, one day a tree may blow down in a storm and some archaeologist of the future will wonder at the brick fragments exposed. A ‘lithic scatter’ of crushed house bricks.

You’d have liked a decent house, with a bathroom.

*

Three human landscapes, all but vanished. There are no great buildings to show for all those lives. The hunter-gatherers managed for thousands of years, living lightly on the land. Then the pastoral/farming times, more thousands of years, until its abrupt halt. Then industry, extractive and powerful, which changed the landscape and lasted not much more than a couple of centuries. The pits, the bings, the railway cuttings, opencast gouges … and now there comes reclamation and restoration: where the miners’ houses stood, a new forest grows.

Up on the moors, in the Highland glens, on shores and mountains, islands and Lowland riversides, everywhere in Scotland there is evidence of occupation. They are faint traces, some deliberately destroyed, but marks nonetheless of generations who left little of themselves behind. They are testament to ordinary people who arrived here and lived out their lives and raised families in the only context they knew, the present. They left no grand buildings, but they built Scotland.

Who built Scotland? We did, because they are us.

2

The Sky Temple

Alistair Moffat

Cairnpapple Hill, West Lothian, 3500 BC

I only knew the way because I had been before, many times. For the site of this unique and remarkable place, there are no signs in Linlithgow or Bathgate, the nearest towns. On the northern approach, the B road leading to Cairnpapple Hill, there is a brown Historic Scotland sign pointing left, but when a fork in the road is quickly reached, there is nothing to indicate the correct choice. If I had stayed on the main road and gone left, I would have been taken off in entirely the wrong direction. I knew to turn right up the steeper road and after a short time found the entrance and parked in what is little more than a passing place where another brown sign helpfully pointed out the obvious. Unsurprisingly, no other car was parked there on a bright and blustery April morning.

Cairnpapple is a fascinating place and the public should be shown how to find it. It rewards the effort of a visit with unlikely insights into our prehistory, a long period that is often relegated to a distant second place behind the last 2,000 years of more or less recorded history. It is sometimes seen as pre-history, somehow something less than history. This is because it lacks stories, named individuals, recorded events such as battles, coronations, invasions, elections, and yet for the 11,000 years since the pioneers first came to Scotland after the retreat of the ice-sheets, prehistory is the overwhelming balance of our time here, 9,000 years of experience in one place. It is perhaps worth a road sign, or even two.

What engages my emotions and inclinations is the nature of our prehistory. Precisely because it is anonymous, it is perforce that elusive thing, a people’s history of Scotland. We do not know the names of kings or queens, priests or warriors, and the accidents of survival mean that archaeologists have uncovered the houses of farmers at Knap of Howar, Skara Brae and elsewhere on Orkney and the remains of magnificent religious sites at Kilmartin and Callanish. By comparison, the last two thousand years are well recorded, but very top heavy. Until the Statistical Accounts of the late eighteenth century and the censal returns from 1843 onwards, the voices of ordinary people are largely unheard, their actions not noted. Scotland’s story is all too often told as a recital of lists: of great men, and very few women, battles won and lost, majestic ruins and the exemplary lives of saints. This shortbread tin lid version of our past with endless images of Robert Bruce, Mary Queen of Scots and Bonnie Prince Charlie is wearisome to the point of scunner as the same old episodes and the all too familiar iconography is endlessly recycled.

Prehistory is about mystery. It offers occasional glimpses of an entirely unexpected past, of people who were not like us, of another country that seems not to be Scotland. It is also more than frustrating: the gaps in knowledge centuries long and the map a series of blanks with rare splashes of light and colour. What can the stones and bones of archaeology offer except whispers from the darkness of the long past? How can we piece together fragments, make a coherent picture out of the unmade jigsaw of the millennia before Christ?

At Cairnpapple, mystery clings to the cold stones around the great cairn like morning mist, but the site is not entirely inscrutable – because it can be read, can be at least partly understood. If the visitor is willing to ignore the twenty-first century and allow this atmospheric place to speak, some flickers of why it was made and why it remained a place of profound sanctity for more than four thousand years can light up the darkness. At Cairnpapple, it is important to look but also to listen for the faint echoes of voices racing across the millennia on the windy hill.

As I pulled on a padded jacket and locked my car, I noticed a sign by the gate that told me the cost of a ticket to enter the monument is £5 and that it was ‘open summer only’. And that summer in Scotland ran from April to September. Energised by such optimism, I climbed the steep steps up to the hill. The public is made to approach from the east and I had forgotten how much of the path crosses a long plateau whose edge screens the summit of the hill until the last few yards. If our ancestors took this route, and it is the most easily accessible, they would not have seen what they had come to see until they had reached the edge of the flattish summit. That late reveal might have heightened anticipation. Perhaps a procession sang and played music as it approached the hill. Those crossing the plateau would certainly have been reverent. Cairnpapple may be hard to find now, but once it was a place of great power. The name itself remembers that. The first element is obvious but the second more obscure. Versions of Papple are to be found at Bayble, Paible and Paibeil on the Isle of Lewis and in the name of the island of Papa Westray in Orkney. It derives from Papar, the Old Irish word for a priest. Cairnpapple means the Cairn of the Priests. And not only Christian priests; the building of the great cairn was supervised by priests who celebrated much older beliefs, faiths that have entirely disappeared.

When I reached the gate through the perimeter fence around the archaeology on the summit, I realised that Historic Environment Scotland’s optimism about a six month Scottish summer was just that. The ticket office, a small green Nissen hut, was shuttered and I could find nowhere to make a donation of £5. Having been on the hill half a dozen times, I knew that a bright, graphic spring day should immediately be taken advantage of and I climbed to the highest point, the top of a concrete dome built at the centre of the site. The vistas are vast, breath-catching.

From this little, unexpected hill, only a thousand feet high, almost all of the geography of central Scotland is visible. Out to the east lies Edinburgh, Arthur’s Seat very clear and beyond it the East Lothian coast, the outlines of North Berwick Law and the Bass Rock obvious in the late spring (or summer) sunshine. Too cold to be hazy and with the brisk breeze to keep the clouds moving, I could see the cliffs of May Island out in the Forth and the line of the Fife coast stretching away into the distance. The seamark of Largo Law and further inland the Lomond Hills were well defined, and beyond the Ochil Hills, the southern mountains of the Highland massif, made a jagged horizon. To the west lie the Campsie Fells and, using my binoculars, I reckoned I could make out the outline of Goat Fell on the island of Arran in the Firth of Clyde. That meant I could see clear across the middle of Scotland, from the east to the west coast. South of Cairnpapple the ranges of the Moorfoot Hills (the derivation of my surname) rise and, to complete the panorama, the northern edge of the Pentlands and Caerketton look over the southern suburbs of Edinburgh.

These sweeping vistas are eternal and they are what drew people over millennia to climb the hill and worship. To see it all lie before you on every side is to comprehend the majesty of creation and to know something of the scale of what the gods had made. Our ancestors did not come to the hill because they enjoyed a good view. They did not live in the canyons of cities or were hemmed in by motorways and busy streets: they were farmers and saw views every day. What made Cairnpapple singular for them was its panorama, the way it dominated the landscape even though from its summit many higher hills and mountains rise up on all horizons. And if this was the place where it was possible to see the creation of the gods and all its passing moods and seasons, then it might also be the place where men and women might be able to commune in some way with the divine, to lift their eyes and worship.

From the top of the concrete dome, it is easy to make out the layout of the site, the various versions of the temples and monuments built by our ancestors, but it is impossible to see the first marks they left on Cairnpapple. Some time around 3,500 BC, groups of people climbed up from their farms in the valleys below and lit fires. Gossamer traces of six hearths have been found where branches of oak and hazel crackled and sparked in the wind. Perhaps these were sacred woods, perhaps the fires were lit at the turning points of the year.

Two pieces of very early pottery and two axe heads were found near the hearths and they are symbolic of a new way of life. The transition from hunting and gathering to farming was the greatest, most profound revolution in human history and it took place in Scotland late, in the centuries around 4,000 BC. New people arrived from Europe and they understood how to grow crops and domesticate and husband animals. But before farms could be established, the wildwood that carpeted the landscape had to be cleared, and that made the stone axe the first and most important farming implement. And it appears to have been revered in some way as a gift from the gods.

What archaeologists found were not practical axe heads but something symbolic. Made from igneous rock and polished with abrasives to give a dark lustre, they were too smooth and small to be useful in any way. Perhaps the axe heads were exchanged as valuable gifts or used in ceremonies on Cairnpapple Hill in some unknowable role. One was produced at the great prehistoric axe quarry at Langdale in the Lake District. High up near the summit ridge of the Langdale Pikes, in difficult and dangerous places, there are ancient quarries of volcanic stone. Even though much more easily accessible and workable deposits lie further down the slopes, the prehistoric miners preferred to climb up and hack the rock for their axes out of the highest outcrops they could find. No practical reason for this puzzling choice can be deduced. Perhaps they worked on the summit ridge because it was nearer to the gods, who had possibly touched it with lightning.

The pottery was more mundane but no less important. Farming and the need to store securely its harvests and surpluses led to the manufacture of pots of varying sorts. Hunter-gatherers moved around the landscape in search of seasonal prey and the wild harvest of fruits, nuts, berries and roots; pots were of little use to them, being both heavy and fragile. But when farms made for a more settled life (not that hunting and gathering ceased), good storage was needed, well stoppered against raiding vermin, and pots that could sit and seethe by the side of a cooking fire filled with the great staple known as pottage, a stew of any and all sorts.

Around 3,000 BC a henge was built on the hill and its remains can be clearly seen. I walked around the ditch that had been dug around the highest part of the summit and in places it was still deep. Beyond its perimeter, the upcast from the ditch had been piled up to make a bank. And then at some point, twenty-four timber posts were arranged in a wide circle inside this area. The building of this temple demanded well-organised effort on the part of the community of farmers who lived in the valleys around the hill. This in turn implies a directing mind or minds, someone who introduced the idea of a henge and could unpack its religious significance. This clearly involved a central sense of a holy of holies, a closed-off inner sanctum where mystery happened. But for all its builders on the outside, the henge and its hill were visible from below: it was their cathedral and the timbers a kind of spire.

The bank and the ditch were designed to keep out the many and accommodate only a few, and the timber posts provided a further screen since they are thought to have been six or seven feet tall at least. So that they remained upright in the ever-present wind on Cairnpapple, a good deal of their length would have been planted in the ground. The henge has two gaps for entrance and exit and it seems likely that processions snaked up the hill, around and into the inner sanctum and that these were accompanied by song or chanting and music. Drums and flutes were certainly made and there may have been other instruments that have not survived. Colour may also have brightened these ceremonies. It is easy to forget that classical sculpture, all now grey marble, was painted and at the near-contemporary prehistoric temple complex at the Ness of Brodgar on Orkney, some of the stones were painted with red and yellow ochre and their mixtures.

For a thousand years, farmers climbed the hill to worship in ceremonies lost to us. But the architecture of the henge does allow some reasonable conjecture. Then, as now, what mattered most to farmers was the weather. Would it be a warm and wet spring so that the new grass would flush quickly and feed the ewes, nanny goats and cows so that their milk would be rich for new-born lambs, kids and calves? Would the sun shine in June to dry the tall grass so that good hay could be cut for winter forage, and would there be no wind and rain at harvest time? Bad weather meant hungry winter months, and good supplied surplus. Farmers every day looked to the skies to see what the day would bring and on Cairnpapple Hill the weather over half of southern Scotland can be seen. Did these communities climb the hill to worship and propitiate sky gods? Was that why henges were built in rough circles and ovals – to imitate the courses of the sun and the moon, and more, to be open to the skies so that the gods could see the faithful pray and offer sacrifice? It seems likely.

The hill’s concrete dome was built to protect perhaps the most spectacular of the archaeologists’ finds. An awkward climb down a metal ladder is rewarded with the remains of three graves. Around 2,000 BC, the function of Cairnpapple changed when the henge began to fade out of use as beliefs shifted. But the sanctity of the site seems not to have diminished and for at least two and half millennia it was used for burials. The first of these is preserved under the dome. A massive upright stone, almost 8 feet tall, has been placed at one end of a rock-cut grave surrounded by an oval setting of large stones. This was a monument to a person of great importance, perhaps a king or a queen, and archaeologists found evidence of the burial ceremony. It seems that the corpse was wrapped in a shroud made from organic material, possibly grass matting. A mask of burnt wood was carefully placed over the corpse’s face. Perhaps it was used to hide decay and the wood burnt as an act of purification. Next to the body, a burnt wooden club had been laid.

The most eloquent evidence was found in two beaker pots. One had a wooden lid and both were filled with food and perhaps drink. Beakers from other graves of that period contained a cereal-based alcoholic drink as well as porridge of some kind. Both the mask and the pots seem to me to imply an afterlife. The food and drink may be offerings to the gods but more likely is the sense of sustenance being supplied for the journey through the veil of death to the other side. Before a small cairn was piled over the grave, it seems that it was strewn with seasonal flowers.

It looks as though over four millennia and many millions of funerals, little has changed in the way that we bury our dead. A big tombstone was raised to mark the grave of someone important who believed in an afterlife and the mourners brought flowers and drank alcohol, perhaps in some sort of ceremony whose descendant is a modern wake.

From the dome, I could see a ring of massive kerbstones laid out in a rough circle. These formed the perimeter of the last substantial monument raised on Cairnpapple Hill, probably in the first millennium BC. This was a huge cairn, about 100 feet in diameter but not high. It covered the post holes of the timber henge, long out of use by that time, and under it two cremation burials were found. But they were not the last human remains to be interred on the hill.

To the east of the massive cairn and the dome over the huge tombstone, four graves were found cut out of the rock. Aligned east to west, these are thought to be Christian burials, perhaps dating to some time around AD 600. When I walked over to have a closer look, I could see posies of dandelions growing bright yellow along the grassy edges of the two larger graves. And for some reason, it made me smile.

On Cairnpapple, there is an extraordinary continuity of sanctity. For four millennia and more, people with differing beliefs had climbed the magic hill to look around its stunning vistas, to marvel at the beauty of creation and wonder about the unseen forces that made and changed it.

Each time I have visited the site, I have found myself alone there, and that is both a privilege and a pity. But this last time, I noticed something new. There has long been a tall radio mast to the south-west of the old henge and, painted battleship grey, it has somehow always seemed to fade to near-invisibility. However, planners have given permission for a large wind turbine to be raised to the north of the hill on its lower slopes. And because its white sails rotate in the wind, it is terribly intrusive, distracting. It is a sacrilege and should be removed. Our ancestors deserve all the respect we can give them.

Cairnpapple is a national treasure, a place where the lives of our ancestors are made vivid, a mysterious place whose uncertainties prompt endless interest and interpretation, a place that lies at the heart of Scotland. A place that should be at the heart of our sense of ourselves.

3

Who are You, and What do You Think You’re Looking at?

James Robertson

Calanais, Isle of Lewis, 3000 BC

Two miles from my home in Newtyle, Angus, beside a narrow road that runs along the northern flanks of the Sidlaw Hills past East Keillor Farm, is a decorated standing stone: ‘the Pictish Stone’, as it is known locally. Composed of metamorphic gneiss, it is a foreigner in this land of sandstone. Either ice or humans brought it there. It is six and a half feet tall, two and a half feet wide. Big enough, yet hardly monumental, it makes a modest statement of stony fact: ‘Here I am. I came here long before you and I’ll be here long after you are gone.’ Barring an act of extreme vandalism, an earthquake or a lightning strike, this is hardly disputable.

The stone’s surface is so weathered that without the right light illuminating it from the right angle it is hard to make out the designs carved upon it. Near the top there is an animal – some authorities say a wolf, others a boar or a bear. Further down are other Pictish symbols: a double-disc and Z-rod, and concentric circles near the base which may represent a mirror. What do they mean? I have no idea, which makes me only slightly less of an authority than the authorities. For the truth is, the people who raised and inscribed this stone and hundreds like it left no explanation of what they and their markings say.

There is also great mystery surrounding the Picts themselves. Recent historical research suggests that as a people they had heartlands both north of the Moray Firth in Easter Ross, East Sutherland and Caithness, and south of it in Aberdeenshire, Angus and Fife, but a few of their symbol stones are found much further afield, in Orkney, Shetland, the West Highlands, Skye and the Outer Hebrides. However distinctive the Picts were, they must have co-existed with other people living in all of these places. And then, in about the ninth century, the Picts performed one of the great vanishing acts of history. Their entire culture seems to have been subsumed very rapidly into that of the Gaelic-speaking people of Dalriada as the latter expanded their territory eastward. From that amalgamation or incorporation or elimination – from that benign or enforced union – emerged what became the kingdom of the Scots. The Picts left a great void scattered with these enigmatic message boards, their symbol stones, a void which has been filled ever since by myth and speculation.

I run out to the stone at Keillor often. The route I take varies: sometimes I run through the woods higher up the slopes; sometimes I follow the path along a disused railway line which carried passenger and goods trains from the late 1860s until the mid-1950s; sometimes I take a path in front of Bannatyne House, where in the 1570s George Bannatyne, an Edinburgh lawyer, retreated from the plague and compiled a manuscript of Scottish poetry, without which much of the work of the Renaissance Makars would be lost to us. But whether I am only running to the Pictish Stone and back, or whether I am going further, I cannot pass it without touching it. I circle it widdershins – against the movement of the sun, which might be deemed unlucky by some but I am left-handed and it seems natural to me – and touch it, front and back, before moving on. I don’t know why I do this. It is a habit born, no doubt, out of some superstition that would crumble on examination, but I have a positive feeling about this stone, and a strong desire to renew contact on each visit. I feel as if I am touching something beyond myself and my time.

In the 1830s, when it was first recorded, the stone was intact, but by 1848 it had cracked near its base, and the bulk of it was lying on the ground. Maybe lightning has struck once already. A few years later the stone was re-erected and secured in place by iron clamps, and these have held it upright ever since. My hand, touching it, connects not only with the touch of the people who restored it, but also with people who were here thirteen centuries ago – or perhaps still further back, for St Ninian is supposed to have brought Christianity to the southern Picts in the sixth century and the stone’s carvings appear to be pre-Christian. The grassy mound upon which it stands is a tumulus, or burial mound, and cists containing cinerary urns are said to have been dug from it in Victorian times. Perhaps the mysterious symbols relate to important individuals, long dead, burned and buried; perhaps the stone is a signpost pointing out of this world to another. Who, now, can tell?

*

Long ago there were people in this country called the Pechs; short wee men they were, wi’ red hair, and long arms, and feet sae braid, that when it rained they could turn them up owre their heads, and then they served for umbrellas. The Pechs were great builders; they built a’ the auld castles in the kintry; and do ye ken the way they built them? – I’ll tell ye. They stood all in a row from the quarry to the place where they were building, and ilk ane handed forward the stanes to his neebor, till the hale was biggit.

The publisher Robert Chambers, in his Popular Rhymes of Scotland