Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Luath Press

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

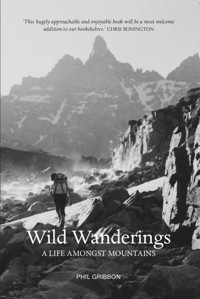

Phil Gribbon's decades of mountain exploration include over 100 first ascents in the Arctic. Filled with humour, honesty and captivating descriptions of his journeys, this book is the amazing untold story of one of the world's greatest mountaineers. Wild Wanderings: A Life Amongst Mountains is by turns thrilling and fascinating, surprising and entertaining. Follow Phil through the ups and downs of a life spent in pursuit of the wilderness.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 315

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

PHIL GRIBBON is a mountaineer, writer and retired physics professor. He has written for the Polar Record, the Canadian Geographical Journal, the Alpine Journal and the American Alpine Journal, as well as the Scottish Mountaineering Club and Irish Mountaineering Club journals. A key figure in Arctic mountaineering and exploration in the ‘60s and ‘70s, Phil has made over 100 Arctic alpine first ascents and has led expeditions in Greenland, the USA and Canada. Born in Cannes in 1929 and raised in Northern Ireland, he moved to St Andrews in Scotland in 1961 and has lived there ever since. Phil was awarded the Polar Medal by HM Queen Elizabeth in 2014.

First Published 2018

ISBN: 978-1-910745-94-6

The author’s right to be identified as author of this book under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 has been asserted.

The paper used in this book is recyclable. It is made from low chlorine pulps produced in a low energy, low emission manner from renewable forests.

Edited by David Meldrum

Typeset in 11 point Sabon by Lapiz

Printed and bound by Bell & Bain Ltd., Glasgow

Text and illustrations © Phil Gribbon 2018

This book is dedicated to Margot my better half who, after contemplation, let me do my thing, alive to all those wild and wondrous places

Contents

Foreword

Introduction

Synopses

Who’s Who in the Book

1. No Entry for the VeePees

2. Slalom in the Sun

3. No Place to Go

4. Getting the Wind Up

5. Tour de Baker

6. Mayday on Meagaidh

7. Stepping Wearily and Back We Go

8. Night over the Gorgon

9. The Remains of the Day

10. The Awesome Cauldron

11. The Fearless Alopex

12. Catching the Caora

13. Three Hits and a Miss

14. Summer Seas to Winter Woes

15. The Great Prow

16. On the Pommel of the Knight’s Saddle

17. Imprinted on the Nose

18. When I was Sixteen

19. Gripped in the Crypt

20. Going, Going, Gone

21. The Black Stairs

22. A Bridge for Troubled Waters

23. Up and Doon the Watter

24. Five Times Lucky at Ben Alder

25. Climbing in the Canadian Northland

26. Welcome to Farewell

27. Time for Tea

28. Madman’s Tour

29. Dancing with Sticks

30. Burn Big Grey Hill, Burn

31. Och, My Ould Vibramers

32. Last on the List

33. Craiglug Lost in Translation

34. A Figment of Time

Foreword

IN THIS COLLECTION of climbing tales, Phil Gribbon chronicles episodes from his long lifetime as a mountaineer, taking the reader from early days in Ireland, to the Arctic and the Far East, but mostly to Scotland, where he has made his home. Somewhat after the questioning and irreverent style of Tom Patey and Geoff Dutton, these stories paint a whimsical, yet at times profoundly analytical picture of our sport and its practitioners. This hugely approachable and enjoyable book will be a most welcome addition to our bookshelves. I thoroughly enjoyed reading it.

Chris Bonington

Introduction

HAVING CLIMBED, wandered about, argued and drunk with Phil Gribbon for some 50 years, I suppose I’m in some sort of position to write an introduction to his book. To comment in a critical way on Phil’s writing is simply beyond the scope of what I can attempt here: I’ll leave that to other critics.

I’ve sometimes tried to write about my experiences with Phil and some of these articles and stories have been published, usually in the Scottish Mountaineering Club Journal. I say ‘stories’ as well as articles because sometimes when I write about mountaineering I cast what I have to say in the form of fiction. This allows me to preserve the essence of the experience while departing a little from what actually happened. Adopting different names and backgrounds for the characters also lets one stand back from the facts and perhaps understand them a little better – it can even work for oneself.

When Phil was in his late 30s and early 40s he had the sharpest, most sarcastic tongue of anyone I’ve known. Not even the late Archie Hendry could match him. Woe betide the undergraduate who made some pretentious or pompous remark, he (less so she) would be sliced in half by a very sharp phrase. In those days Phil was a man of few words, most of them sardonic. By this means he taught us, and by ‘us’ I mean the large company of students he climbed with, to grow up a bit and not be quite so foolish. I don’t know where the acid came from but it was part of his makeup and we were very much in awe of him.

Myths about Phil abounded in the student community: he had been in the Foreign Legion, he had been in prison, there were dark secrets in his past. My wife once made the ghastly error of asking if one of these myths was true. She was met by a silence so deafening that ‘neither durst any man from that day forth ask him any more questions’. This acerbity and a certain personal aura made him the perfect person to lead student expeditions to Greenland.

I was chosen to go on the expedition to Upernivik Island in 1969. However, a first year spent play acting, drinking, and falling madly in love with a dark haired student with lovely green eyes meant that I failed all my exams and couldn’t go. In a way, I’d let Phil down and he could just have abandoned me. But he didn’t. I got a nice little note from him telling me to pass those ‘durned exams’ and who knows what might happen in a couple of years’ time. It lightened my despair and I dimly began to realise that underneath all the bitter sarcasm there lurked something else. Over the ensuing years I was to learn that he is a most faithful friend.

Two years later, having snared my green-eyed student for life (at least I hope so!), I got the chance to go on the St Andrews University expedition to the Cape Farewell region of Greenland and that was where my friendship with Phil really began.

In the stories I’ve written about climbing with Phil, he appears as the dour Yorkshireman George Reddle; the fabled dourness and tight-fistedness of the Yorkshireman seem an appropriate representation of ‘that dour Ulsterman’ (as I once heard a colleague of his describe him). Being ‘tight-fisted’, however, as one of my stories shows, has nothing to do with lack of generosity; it is simply a rather amusing quirk of character. I cast myself as Patrick O’Dwyer: a not so gentle hint at my Celtic ancestry.

In Untrodden Ways (SMCJ, 2007) Reddle and O’Dwyer set out to climb on a pleasant crag in the North West:

Reddle led through, exclaiming over the excellence of the rock... To his right was a steep slab devoid of holds, and to his left an easier traverse… O’Dwyer could sense the temptation of the steeper way tugging at the older man. He remembered many times watching the soles of Reddle’s boots vanishing upwards, remembered also how Reddle would pause before making the vital move and make some light-hearted remark. Now, he hesitated... O’Dwyer could sense a trembling in the rope...

‘George,’ he shouted up, ‘it looks much easier to the left.’ Reddle looked down at him:

‘Don’t you fancy going right, eh?’ It was like a wasp sting from the past. O’Dwyer winced...

Ian Hamilton, a perceptive judge of the WH Murray Prize entries that year, said the story was about ‘the age-old theme of the master/pupil relationship’. And there was the pupil, in his late 50s, being put firmly in his place.

However, as my story goes on to relate, there was an evening in Greenland when Phil and I canoed back to base-camp across Tasermiut Fjord. It was late, we were both tired and when, manhandling the canoe up the beach, I clumsily dropped my end, Phil made a snappish remark. I apologised at once, accepting responsibility. Somehow, from that moment on, I wasn’t just another student on an expedition but I sensed that he actually had time for me as a person. He has always been very devoted to long-lasting relationships and ancient traditions and I think he perhaps sensed that I felt the same. Oddly enough, now that I think of it, we had something else in common: we were both married; none of the others were, and, although Phil would never in a thousand years have admitted to missing Margot (although I’m sure he did), he probably noticed that I was missing Angie and that may have added to the feeling of closeness.

Although stingy with food – he once, rather reluctantly, gave me a dry rock-cake at the top of a climb on Creag Meagaidh – even more so with drink, and tight-fisted with money to the extent that to this day he goes round in the most ragged and antiquated climbing clothes and is delighted to use other people’s climbing gear (and you certainly wouldn’t want to trust his), Phil is not at all stingy with the things that really matter.

I remember with deep gratitude a visit he made to us when we were in exile in darkest Merseyside and my ill-fated career as an English teacher had come to a shuddering halt in a nervous-breakdown. I remember when I opened the door to him and we shook hands he just looked me in the eye and said:

‘Are you all right?’

I said, ‘Yes.’

And he said, ‘Really?’

We sat in the garden for a whole sunny afternoon and Phil looked through Tom Strang’s recently published Guide to the Northern Highlands. It wasn’t anything he said, but I just felt so much better afterwards.

As many of the stories in Wild Wanderings show, Phil loved going to the CIC hut on Ben Nevis. He delighted in its special atmosphere and jestingly, but very sincerely, venerated its long-suffering custodians. Our old friend and fellow Greenland expeditioner, Mike Jacob, captures Phil brilliantly in some of his articles. In Greenland, Phil was the ‘Gaffersnake’ on our Snakes and Ladders board. Thus on the Ben:

The shiny new karabiner that the Gaffersnake had discovered now glinted incongruously at his waist, looking out of place amongst his small collection of faded old tapes. I think that most of his gear had been found on a climb in Ireland when we had discovered every stance littered with abandoned goodies.

On the same occasion:

I looked up to see the Gaffersnake’s loose crampon bindings on a pair of what looked like old walking boots; Terrordactyls hung from his wrists and these concessions to modern (sic) ice climbing matched his miner’s helmet. I remembered him climbing at Lochnagar with his trusty old walker’s axe, and crampons with no front points, as we chopped steps up in yet another storm. (SMCJ, 1993, pp185-6).

The Terrordactyls weren’t even his originally: they belonged to STAUMC. Phil borrowed them for such a lengthy period that ownership became mysteriously transferred.

After a glorious day on Observatory Ridge:

Very early the following morning the Gaffersnake disappeared out of the hut, apparently, and strangely, concerned about being late for work. I think he was trying to avoid scrubbing his porridge pot. I yelled after him, but he was too far away to hear my shouts questioning his parenthood and merely turned and waved. (SMCJ, 1993, p187).

More recently Mike has described some of his earlier experiences with Phil at the CIC:

Phil stirred in his wafer-thin sleeping bag. Even as I felt around for my shirt he was up and had snatched the last ring on the stove. I sank back onto the bunk as he poured two mugs of someone else’s tea and handed one up to me. (SMCJ, 2013, p411).

Phil Gribbon is one of nature’s survivors:

Phil, who never wore a watch until he acquired a freebie – and never, to my knowledge, used a compass, but managed only rarely to get lost – had managed to take the seat nearest the fire.

Naturally the happy pair had arrived at the hut after the usual appalling walk up the Allt a’Mhuilinn:

Some strange Irish logic of Phil’s tried to convince me that mine was the correct introduction to a Club Meet at the CIC hut. (SMCJ, 2013, p412).

I’m afraid this introduction reads more like character assassination, but I’m sure Phil will enjoy the jokes at his expense and, no doubt, get his own back. To be serious for a moment, this book is crammed with the life of a man who has been perceptively absorbed in the mountain scene all his days. His work contains many subtleties and different levels of meaning – not all of which are immediately apparent.

One can make much of the master/pupil relationship and, of course, it is there, but the only actual word of instruction I can remember Phil giving me was on Shadow Buttress on Lochnagar in 1973.

‘Don’t take such big steps,’ he said. A remark with a much wider application, I feel. A good teacher doesn’t have to say very much.

On one famous occasion when we camped in spring sunlight by Loch Maree on the Club’s Easter Meet, our much loved Hon Secretary called us a pair of ‘skinflints’ for not staying in the hotel. Of course the remark was a joke, but Phil was aghast:

‘What! We’ve had our dinner looking up at Slioch, utterly at one with nature and you lot are sitting in a plastic bar...!’

Perhaps George Reddle should have the last word. After a cathartic row on the way back from a failed attempt on the Pinnacle Ridge of Sgùrr nan Gillean, when an abseil rope got stuck and all sorts of mayhem ensued, Patrick O’Dwyer felt the need to make a sincere apology to his old friend:

‘That’s all right, lad,’ said Reddle, lowering the paper he’d borrowed and smiling his strange smile. ‘I’d get you a drink, but I’ve left my wallet in the hut.’ (SMCJ, 2001, p.503).

Read this book, then read again, with increasing pleasure.

Pete Biggar

Hon Editor

Scottish Mountaineering Club Journal

Synopses

Tale 1

The Club’s Vice Presidents find themselves barred from their hut on Ben Nevis. Later arrivals suffer the same fate. Eventually someone appears with a key and everyone piles into the welcoming depths of the old revered building.

Tale 2

A climbing team wend their way up the sparkling snows on the sunny side of Ben Nevis. Slalom is the name of their route, but fancy downhill piste skiing it never can be. What more can they ask of a winter’s day that offers such enjoyment?

Tale 3

Our trio of tired but satisfied mountaineers return to the overcrowded Ben Nevis hut and find they are not welcome. They are called to explain themselves while the assembled hordes look on. A few vital diplomatic words are offered and peace descends. Everyone relaxes and settles down contentedly.

Tale 4

Two inmates cooped in the Nevis hut by the wild weather decide to venture out and make a traverse of the Carn Mor Dearg arête. All goes well until they are stopped by a frightening squall and pinned immobile on a dangerous exposed slope of ice close to the summit.

Tale 5

Two lost mountaineers escape from the snowy rim of a volcano in Washington State, and find themselves under the cloud layers on the glacier in an unfamiliar valley. They begin an up-and-down circuit round the mountain and are benighted. Dawn finds them close to their starting point.

Tale 6

A helicopter decides to crash into a bog and expects no one to witness its demise. Two hopeful climbers looking for sparse snow in a bare gully in the corrie of Creag Meagaidh hear a big bump and find themselves observing an aerial mishap and its peculiar consequences.

Tale 7

A wintery trip back from a distant Cairngorm bothy nearly ends in disaster. With exhaustion and exposure taking their toll the party decides to turn back. In the gathering dusk they find the emergency shelter at the Fords of Avon. Marooned overnight they are bewitched and feel they are touching close to another mysterious realm.

Tale 8

The high traverse of an attractive jagged ridge in Greenland provides a trio of expedition members with sleepless hours of absorbing action as they climb onwards in the land where the lingering northern light persists though the darkest hours of night.

Tale 9

Two elderly mountaineers, backpacking supplies up to a higher campsite, make an unwelcome discovery in the melting crust of an alpine glacier in the Tien Shan Mountains of China. No explanation appears to be satisfactory: the reader perhaps can give a better answer.

Tale 10

Four campers crammed into a tiny tent in a misty high corrie in the Mourne Mountains experience a strange, unsettling happening for which they never had a rational explanation.

Tale 11

A friendly arctic fox finds the explorers camping on the tundra to be a great source of interest. On its nightly visit it keeps them amused after the days when they explore some of the unclimbed mountains close to a DEW line station at Cape Dyer on Baffin Island.

Tale 12

The hills are alive with the sound of sheep chewing up the landscape. You meet them here, you meet them there. Silly sheep, getting stuck, getting rescued, endangering their selfless saviour. Ungrateful beasts, but I like them.

Tale 13

Whether you are climbing up a local Fife outcrop, a secluded Solway sea cliff, or circumventing a huge jammed chockstone on the Buachaille, there are things that can happen with unpleasant results. However when a falling boulder tried to wipe me off a Greenland ridge it missed me, thank God.

Tale 14

A canoe voyage to an island close to Skye and then a sunny traverse of its biggest bump leads to a strange lost loch. Back on the Skye again a rough ridge recalls a futile attempt to make a traverse of its wintery shrouded towers.

Tale 15

The remarkable rock feature of the Great Prow on Blaven in the Cuillins of Skye is given its first ascent. Its secluded position away from the mainstream climbing area ensured that its challenge was not known to other exploiters of choice virgin routes. Just choose the right place at the right time with the right people.

Tale 16

Four toughened climbers of the Scottish East Greenland Expedition 1963 climb Rytterknægten – one of the most immaculate and beautiful peaks that rises above its satellite family and within sight of the pack ice drifting down the east coast of Greenland. They make their leisurely way up the north ridge to spend the hours of night beside the summit rocks.

Tale 17

Close by the Cioch Nose in Applecross, a route distinguished by a totem-like pinnacle was selected from the offerings of the guidebook. Having identified the route the leader scrabbled up without any conviction and, while hauling on a flaky wall, the mountain shattered. He went down rapidly and was sorely impressed.

Tale 18

On a perfect early summer’s day two climbers make a leisurely approach to the classic Cioch Nose in Applecross. They join the end of the queue and, with no pressure from any other climbers, they savour pitch by pitch its delights and complete the route in their own good time.

Tale 19

Three rock climbers attempt the classic CryptRoute within the Churchdoor Buttress on Bidean nam Bian on the south flank of Glencoe. They fail to solve the intricacies of its dark labyrinth of passages and retreat ignominiously while all the time offering feeble excuses to each other.

Tale 20

Three mountaineers embark on a wintery traverse of the Aonach Eagach ridge on the north side of Glencoe. All goes well until they come to the final descent in the gathering darkness of evening.

Tale 21

The freezing of a waterfall in the Mourne Mountains gives a rare opportunity for two friends to make its first ascent before it melts away or tumbles down in a soggy cascade of mushy ice.

Tale 22

A major repair or, as some would say, a complete rebuilding of a broken bridge across the Carnach river, which feeds into the head of Loch Nevis in Knoydart, provokes some controversy and warrants the appearance of a well-known journalist intent on defending the last great wilderness. The work teams pause, everyone looks on, some friendly gestures are exchanged and they all part amicably.

Tale 23

Years later a minor repair of the Carnach Bridge was arranged. Repairs done, they explore upstream to find a fisherman in the throes of delirium, and returning to the shore the team is evicted unceremoniously by the local strong men. When dumped in a damp midge-infested Inverie, they camp, unaware that the noises off signifies a skirmish between rival village clans.

Tale 24

Sometimes it takes a few attempts to get up some of the Munros. My outings to successfully climb one of the most inaccessible hills, Ben Alder in the Central Highlands, gave a clutch of memorable days. This was done with a galaxy of different ladies whose companionship helped to fill the weary miles and imprint deep memories of time well spent.

Tale 25

Two explorers penetrate into the restricted northland where the free world kept an eye on the Red Menace somewhere over the pole. They came to climb a few nameless mountains close to Baffin Bay. They took their photos and sent them off to the National Geographic magazine for consideration who, in turn, mislaid them for weeks. They considered themselves to be jolly fine fellows, but the photos were very ordinary and their mountains quite mundane.

Tale 26

Two expeditions meet in the street of Nanortalik, the southernmost settlement in Greenland. The long-established Scottish party have conscripted the freshly-arrived Irish party to participate in a four nation football tournament. There is no way out for the exhausted arrivals. Both teams, not wholly unexpectedly, get eliminated in the first round, and of course the Greenland team win.

Tale 27

It is easy to be highly motivated to get to the topmost tip of an unclimbed mountain in Greenland but to return by the same long and convoluted route needs someone with much drive to force the pace. Here is someone capable of taking this necessary role and who careers ahead, followed by his lagging companions. They struggle to keep up and force themselves to stay awake through the long faint glimmer of the passing night.

Tale 28

The party decides to traverse a long ridge in Greenland dotted with minor peaklets. They find abrupt gaps cutting through the ridge and avoid such obstacles by following elaborate ledge systems stuck on its flanks. Clouds lower, gloom descends, the rain drives in. In the misted dark the slowest member staggers down, his hand dripping gore…

Tale 29

This is the life story of our two sticks that shared in many escapades on the Scottish hills. They were found objects, abandoned on upland pastures, and in turn they became lost objects waiting beside the ocean for a further reincarnation in the hands of new owners.

Tale 30

A wanton fire sweeps quickly across the rocky slopes of a mighty mountain in Torridon. Worried villagers wonder if their homes are under threat and stay vigilant through a long night lit with dying embers, pinpointed on the hillside. Morning brings seawater showers from a helpful helicopter while the fire brigade holds itself in readiness for any further encroachment on nearby homes.

Tale 31

Old boots, condemned to a garbage bin in a car park of a national park in the state of Colorado in the USA, warrant a panegyric elegy. To their erstwhile owner it was a mere question of a goodbye to fine rubbish.

Tale 32

Collecting the Corbetts can rival ticking off the Munros as a pleasurable and healthy pastime, but there comes a time when the task seems complete, or is it? The guidebook stated that there was one hill with two very separate summits of the same height and both should be done for completeness and personal moral certitude. This leads to two further attempts and eventual success. That’s it, isn’t it?

Tale 33

An ageing habitué of the delights of a Fife crag goes to see if it still attracts climbers. He sadly finds it overgrown and abandoned but as he walks beneath its familiar cracks he feels within a stirring of many pleasurable memories that this small stretch of cliff has given his soul over many decades.

Tale 34

The Professor sits alone in front of a miserable fire in an old cottage that survives at the limit of habitation on the slopes of the Mourne Mountains. He reads though the logbook where others have tried their hand at creative masterpieces, and for something to do he adds his own feeble piece. He reads of a nasty outing up there by the granite tors, a poetic exposé of lands of pleasure, and a philosophical bout of self-awareness. Time passes…

Who’s Who in the Book

Dramatis personae: the Tales and cast in order of appearance

Tale 1

Crocket and Smart, who feature as the Veepees, were in their due season Vice-Presidents and later Presidents of the Scottish Mountaineering Club. Ken Crocket was a notable climber at the forefront of winter climbing. In 1986 he wrote the first comprehensive mountaineering history of The Ben, Ben Nevis: Britain’s Highest Mountain, and is now completing a comprehensive trilogy covering the development of mountaineering in Scotland. Iain Smart, an anatomist, who found an academic niche away from the winds of professional competitiveness, was greatly gifted with original insight from within the depths of his philosophical mind. An old friend dating back to years spent in British Columbia during the 1950s, he died in 2016.

David Meldrum: his contribution to my climbing days speaks for itself within these pages. Many memorable days we have spent on gabbro and granite from which one savours still the moments of hesitation when we baulked on minute holds shrinking yet smaller on the Crack of Double Doom in Skye. We swore to return some day but never did. One admits, too, that this book would never have existed without its initiation through his persistence and skilful competence. I am forever indebted!

Tale 2

John Thurman, a dynamic, thrusting, enthusiastic geography student who subsequently joined the military in time to see active service in the Falkland Islands. There at Port Stanley in a fairy tale romance he met and subsequently married the governor’s daughter. Well done, sir!

Tale 3

Auld Dawg, Daft and Popsie were an over-exerted trio trying to enter the hallowed precincts of the CIC climbing hut. Auld Dawg was me. Daft was a gangling novitiate, a dabbling absorber of Highland atmosphere, and the originator of debauched eating competitions. He, too, was the budding author Richard Henderson, who created a tantalising, treasure hunt novel entitled Chasing Charlie, based on the flight of the defeated Charles Edward Stuart. The prize for whoever might solve the clues within was to uncover the treasure, an allegedly vast cache of an inexhaustible lifetime’s supply of whisky. The eye-catching blonde Popsie was Carolyn Popper who was good on the rope, and useful to sway the objectors wishing to reject the tired trio from their well-deserved overnight home. Within the hut an outspoken nameless Big Cheese had taken the role of inquisitor and tormentor in chief of the exhausted climbers.

Tale 4

Unable to move and stuck on an icy slope in a raging gale, David Meldrum and I diced with the deadly intentions of the God of the Winds, but we escaped and lived to climb another day. By contrast in Tale 16 in the peace of an early summer’s day we shared leads up the classic Cioch Nose in Applecross.

Tale 5

Les MacDonald was an emigrant who moved from Geordieland to Vancouver on the west coast of Canada. Once upon a time he picked up two wandering hitch-hikers making for Skye. One lassie he terrified beyond recall by coaxing her up the fearsome exposure of a splendid route of character above the Cioch on the cliff of Sron na Ciche. This initiation was not helped by wearing sandals tied on with string. My wife subsequently always baulked at vertiginous heights.

Later, above the densely forested Canadian mountainsides, Les and I had long days climbing up attractive alpine peaks. However these activities risked a late weekend return to some disapproval from both family and workplace. We shared such outings, although the excessively motivated Les climbed, skied, swam, and ran triathlons well beyond my abilities. He was one of the pioneers of the smooth granite boiler-plated cliffs of Squamish Chief above Howe Sound and once, while high up on the face, he and his partner watched their motorbike being stolen and driven away from a roadside layby by two inconsiderate opportunistic thieves.

Tale 6

Pete Biggar, a long-time friend and the reliable route leader for an ageing mountaineer; given to creative writing and, as Editor of the SMC Journal, is skilled in separating gold from dross. In Tale 17 I tried to excel at the sharp end of his rope but was promptly brought down to earth.

Tale 7

David ‘Cludge’ Henderson and Ross Millar were fellow students, and, as was all the rage at the time, they were dedicated hillbashers and Munro collectors. Cludge, always appearing to relish his sobriquet, was given to electronic gadget acquisition. Once he packed his rucksack with a portable television set and hauled it up Seana Bhràigh, a remote Munro in the Sutherland hills in order to follow Scotland’s football team playing Yugoslavia in the World Cup. Later he became an irreplaceable unelected long-serving President of the Corriemulzie Mountaineering Club, although there was rumoured to be a rival president lurking in North America.

Bill Led(ingham), aka The Colonel, was gifted with a regimental posture and an emphatic tone of voice that brooked no querulous disagreement. Many a frenetic ceilidh in a crowded bothy has been filled with the semi-musical sounds coming from his battered leaky accordion. One Hogmanay night this musician was required to play while forced into a room packed beyond the dictates of health and safety in Shenavall bothy. I counted 65 squashed bodies but the circumstances were hardly conducive to accurate recollection.

Tale 8

The traverse of the Gorgon was made by Stuart Howarth, Iain Smart and me. Iain considered that the erratic behaviour of his two companions warranted the sobriquet of ‘silly billies’, or something along those lines. Stuart was a very unqualified medical student who never completed his medical training. One wonders if this was consequence of the self-doubt induced by an unwelcome emergency in these Greenland mountains. He and Jimmy Gilchrist, the expedition treasurer, who was suffering from worsening quinsy, were marooned and barely surviving below a seeping dripping boulder while afflicted with continuous rain storms. There was penicillin available but a decision to use it was not made. Eventually when the retreating pair succeeded in reaching the base camp the Good Samaritan Colonel canoed through the night to get a rescue boat to bring the sick patient to the hospital at distant Sukkertoppen.

Tale 9

Mike Banks was a marine commando climbing instructor, explorer, expedition leader and a very well-respected mountaineer and author. In the big league, he made, with Tom Patey, the first ascent of Rakaposhi (7,788m) in the Karakoram Mountains of Pakistan in 1958, and in the very minor league made with me an ascent of Eric’s Peak (4348m), which we named in honour of Kashgar’s climbing consul Eric Shipton. Joss Lynam, who also features in Tale 26, Barry Page, and Paddy O’Leary, the author of The Way that We Climbed, a history of Irish mountaineering (2014) were the other semi-decrepit members of this Saga-sponsored expedition to China.

Tale 10

She, a nameless one, and her three companions had wedged themselves inside a Yankee bivvy tent within whose walls they could sample what US soldiers put up with in the last big war. The other three were Scout Troop, Maurice MacMurray and me. Mac, a philosophical pessimist given to argumentative outpourings, a natural writer of ironic humorous verse, and impecunious to the extent that one bottle of Guinness could last all evening, was on his way to becoming a reluctant and brief brat-basher, before moving on as an outdoor education activities instructor.

Together Mac and I created several wee routes like Christmas on Little Binnian in the Mourne Mountains. We drifted out of our climbing hut, across the bleak moorland, passed the abandoned granite quarry detritus, into the gully splitting the oversized rock pimple, spotted a crack, climbed it, went up and onwards to finish teetering up a blanched groove at the edge of vacuous space, then we went home to her Christmas dinner, and that bottle of Guinness supped by the glowing fireside.

Tale 11

My companion in Baffin Island was Brian Rothery, a Dubliner who had emigrated to Montreal, who, with the Club de Montagne Canadien members, climbed extensively in the undeveloped oversized outcrops of Ontario, Quebec, and New England. Together we have bridged up wide corners, whacked pitons into steep virgin cracks, watched the munching porcupines swinging contentedly on the tree branches, and sweated up strenuosities in humid evenings beside the St Lawrence River. He later returned to Dublin where, on a visit, I was appalled to find him digging in his back garden and pushing the spade into his incipient hayfield while wearing his former pride and joy, those trusty climbing shoes. The Arctic trip resulted in Brian Rothery, while journeying daily into work by train, writing a worthwhile novel entitled The Crossing, inspired by our attempt to cross a tumultuous swollen river and how the book’s hero finally solved the problem. Well worth a read I have to say, of course.

Tale 12

Barry White was a political journalist working in strife-torn Northern Ireland during The Troubles. A one-time motorbike user, he occasionally required escape routes up rough lanes or made soft impact landings in haystacks that were being transported in a tractor’s trailer. Younger brother of John White, he was known as the Young Man, with all that entailed, by his fellow mountaineers. Once he was admonished by his starving friends for hiding a bread crust under a moraine boulder in the French Alps.

John who, as ‘Scout Troop’ features again in Tale 21, and whose walking mode was a stooped amble with head hunched under his paddy hat, was a venerable, socially-aware figure. More significantly he was the irresponsible friend who introduced me to the climbing game. His nickname came from the mighty rumble made on the wooden floor of a youth hostel when he strode across in his oversized boots: it was like the tramping of a troop of Boy Scouts.

Charlie ‘Pingpong’ Boyd, a refugee from the insurance business, became a mountaineering instructor and married the secretary at the Outward Bound centre at Eskdale in the Lake District before quitting and becoming a gifted teacher of English. His nickname was unfairly attributed to him by the versifier Mac because this double-syllable nickname fitted slickly into one of Mac’s choral ditties. Charlie suffered from mishaps: once he was the sole participant in a moonlit walk across the Mourne Mountains but he ended up off course, alone, damp and ill-equipped, benighted amongst abundant sheep droppings in a tiny granite block shelter on the top of Commedagh, the Mourne’s second highest summit.

One recalls his beat-up car whose upper bodywork was not properly attached to the chassis. His driving bravado gave terrifying moments as the car rocked alarmingly when cornering. Once when returning from Donegal in the dark it was necessary for the passenger to lean out of the side window and wipe the rain-spattered windscreen by hand in the absence of workable wipers.

Tale 13

Peter Riedi was a work colleague with impressive alpine experience whom I was introducing to some little local outcrops. After his hospitalisation he took to health-giving hillwalking.

Dougie Lang never lost his enthusiasm for rock, ice and snow adventures on his native hills. In searching out secret undeveloped rock crags he helped to discover routes like Ardverikie Wall, one of the gems of its genre. Over the years he was a dedicated habitué of the CIC Hut. He and his partner were the last climbers to forge new routes using traditional ice axe techniques up the last big winter unclimbed lines that threaded its cliffs.

Mike Jacob was my companion when I attempted, Samson-like, to bring down the fragile rock pillars of Dumfriesshire and chop off a number of fingers. Many excellent days we have spent whacking our ice tools into crisp reassuring névé in the recesses of the medium grade routes on the Ben, or wriggling airily up on crimped holds at Craig-y-Barns and stealing summer days dancing delicately up classic climbs in Lakeland valleys.

Tale 14

As the years go by, the climbers of yesteryear looked for more gentle activities in the wide open spaces. This tale, involving two fruitful minor mountain days shared with a pair of long-time climbing companions, gifted some sport by the Isle of Skye.