8,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Grove Press UK

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

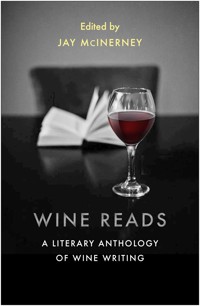

Country & Townhouse's Best Book for Christmas, 2018 A delectable anthology celebrating the finest writing on wine. In this richly literary anthology, Jay McInerney - bestselling novelist and acclaimed wine columnist for Town & Country, the Wall Street Journal and House and Garden - selects over twenty pieces of memorable fiction and nonfiction about the making, selling and, of course, drinking of fine wine. Including excerpts from novels, short fiction, memoir and narrative nonfiction, Wine Reads features big names in the trade and literary heavyweights alike. We follow Kermit Lynch to the Northern Rhône in a chapter from his classic Adventures on the Wine Route. In an excerpt from Between Meals, long-time New Yorker writer A. J. Liebling raises feeding and imbibing on a budget in Paris into something of an art form - and discovers a very good rosé from just west of the Rhone. Michael Dibdin's fictional Venetian detective Aurelio Zen gets a lesson in Barolo, Barbaresco and Brunello vintages from an eccentric celebrity. Jewish-Czech writer and gourmet Joseph Wechsberg visits the medieval Château d'Yquem to sample different years of the "roi des vins" alongside a French connoisseur who had his first taste of wine at age four. Also showcasing an iconic scene from Rex Pickett's Sideways and work by Jancis Robinson, Benjamin Wallace and McInerney himself, this is an essential volume for any disciple of Bacchus.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Ähnliche

A LITERARY ANTHOLOGY OF WINE WRITING

WINE READS

EDITED BY

JAY MCINERNEY

First published in the United States of America in 2018 by Grove Atlantic Inc.

First published in Great Britain in 2018 by Grove Press UK, an imprint of Grove Atlantic Inc.

Copyright © 2018 by Jay McInerney

Cover design by Gretchen Mergenthaler Cover photograph: wine bottles © Jill Battaglia/arcangel; books © MartinFredy/BigStock

The moral right of Jay McInerney to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of the book.

Every effort has been made to trace or contact all copyright-holders. The publishers will be pleased to make good any omissions or rectify any mistakes brought to their attention at the earliest opportunity.

A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library.

This book was set in 12 point Goudy Old Style by Alpha Design & Composition of Pittsfield, NH

Hardback ISBN 978-1-61185-627-9 E-book ISBN 978-1-61185-931-7

Grove Press, UK Ormond House 26–27 Boswell Street London WC1N 3JZ

groveatlantic.com

1 3 5 7 9 8 6 4 2

CONTENTS

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Introduction

Jay McInerney

Taste

Roald Dahl

A Stunning Upset

George Taber

Blind Tasting

Jancis Robinson

The Notion of Terroir

Matt Kramer

The Wineführers

Donald and Petie Kladstrup

My Fall

Roger Scruton

Wine

Jim Harrison

from Sideways

Rex Pickett

Perils of Being a Wine-Writer

Auberon Waugh

East of Eden, 1963–1965

Julia Flynn Siler

Afternoon at Château d’Yquem

Joseph Wechsberg

from A Long Finish

Michael Dibdin

The Assassin in the Vineyard

Maximillian Potter

Burgundy on the Hudson

Bill Buford

Just Enough Money

A.J. Liebling

from Sweetbitter

Stephanie Danler

Northern Rhône

Kermit Lynch

The Importance of Being Humble

Eric Asimov

The Secret Society

Bianca Bosker

A Pleasant Stain, But Not a Great One

Benjamin Wallace

The Wine in the Glass

M.F.K. Fisher

My Father and the Wine

Irina Dumitrescu

from The Making of a Great Wine

Edward Steinberg

War and the Widow’s Triumph

Tilar J. Mazzeo

Billionaire Winos

Jay McInerney

The 1982 Bordeaux

Elin McCoy

Remystifying Wine

Terry Theise

Contributor Notes

Credits

Back Cover

INTRODUCTION

Jay McInerney

The late Giuseppe Quintarelli once told me that Amarone was “a wine of contemplation.” I was visiting him at his home and winery outside of Verona, and I’d asked him what kind of foods might be paired with this complex, autumnal wine made from late harvested grapes that spend several months drying out, essentially becoming raisins before they are pressed and fermented. His answer suggested that Amarone should be enjoyed without food, with nothing to interfere with its appreciation. And while at the time I found his description apt, it subsequently occurred to me that it fits all wines of quality. Not that fine wine should be enjoyed without food—but that it inevitably inspires contemplation. And, since before the time of Homer, it has inspired commentary ranging in tone from the ecstatic to the analytic. The ancients overwhelmingly favored the former, creating a cult of wine worship centered on Dionysus, whom the Romans adopted as Bacchus. The Greek symposium was inevitably lubricated with wine, and Socrates was clearly a fierce devotee of Bacchus, if not a lush. Writing two millennia later, philosopher Roger Scruton makes the case that wine is conducive to a life of reflection and intellectual adventure in his memoir I Drink Therefore I Am. Socrates’s crabby disciple Plato was a neo-prohibitionist, but the Greek and Roman poets and playwrights penned innumerable paeans to the stimulating and salutary properties of wine, as did their literary successors from Shakespeare and Keats to Baudelaire and Verlaine. These writers inevitably dwelt more on the effects of wine than on description. Modern commentary has tended more and more toward the analytical, toward an attempt to anatomize and quantify the properties of wine, as opposed to celebrating its effects—although Bill Buford, in his short essay included here about La Pauleé de New York, reminds us of the intoxicating side of oenophilia.

The kind of detailed tasting notes that fill so many contemporary publications were unknown until very recently—you won’t find lists of flavor descriptors or technical details in George Saintsbury’s Notes on a Cellar-Book (1920), long regarded as the landmark work of wine commentary in English, though in fact it hasn’t aged very well, despite some pithy observations that still ring true. More recently, no one has been more influential in shaping modern wine commentary—and some would say winemaking—than Robert Parker, whose rise to become the preeminent wine critic in the world is documented in Elin McCoy’s essay on the seminal 1982 Bordeaux vintage, from her biography The Emperor of Wine. Wine critics like Parker perform a valuable service for the consumer, but the writing collected in this volume has been chosen for its narrative and literary qualities; in selecting these readings I undoubtedly favored entertainment and felicity of expression over instruction. Parker’s English counterpart, Jancis Robinson, has penned thousands of detailed tasting notes, which I find terribly useful, but she has also written discursively about her adventures in wine, notably an elegant memoir, Tasting Pleasure, which includes a funny and self-deprecating chapter about blind tasting.

Tasting notes, with their laundry lists of flavor analogies, may be a necessary evil, but I wish all wine critics, before penning them, would heed the advice of Auberon Waugh in his essay “Perils of Being a Wine-Writer:”

My own feeling is that wine writing should be camped up: the writer should never like a wine, he should be in love with it; never find a wine disappointing but identify it as a mortal enemy, an attempt to poison him; sulfuric acid should be discovered where there is the faintest hint of sharpness. Bizarre and improbable side tastes should be proclaimed: mushrooms, rotting wood, black treacle, burned pencils, condensed milk, sewage, the smell of French railway stations or ladies underwear—anything to get away from the accepted list of fruit and flowers.

When I first started writing about wine I was pretty ignorant of the details of winemaking and insecure about my knowledge of the field in general; I favored metaphors and analogies over flavor descriptors and technical specifications. I decided that comparing a California Chardonnay to Pamela Anderson, or a Chablis to Kate Moss, was at least as effective, and certainly more entertaining, than talking about new oak, minerality, and PH levels. I also discovered that the wine world is full of colorful and improbable characters; as a novelist I felt fairly confident of my ability to write about them, and as a reader I’m fascinated by stories of the eccentrics, the fanatics and the criminals of the wine world. Benjamin Wallace’s bestseller The Billionaire’s Vinegar is bursting with all of the above, as is Maximillian Potter’s The Assassin in the Vineyard, a true crime story about the poisoning of the world’s greatest vineyard. Edward Steinberg gives us a compelling portrait of one of the world’s great wine personalities, Angelo Gaja. Tilar J. Mazzeo, in The Widow Clicquot, tells the story of one of the great figures of French winemaking, the brilliant and indefatigable woman who created an enduring empire in Champagne in the wake of Napoleon’s defeat.

The first wine writing I encountered was in novels. My ambition to be a novelist and my interest in wine were both partly inspired by Ernest Hemingway’s The Sun Also Rises. Everyone in the book was drinking wine all the time, and they were all young and jaded and good looking. I wanted to write like Hemingway and drink like Jake Barnes, who at one point downs a bottle of Château Margaux all by himself. As an aspiring novelist I also fell under the influence of Brideshead Revisited, and the semi delirious wine commentary of its protagonists Charles Ryder and Sebastian Flyte who spend an idyllic summer trying to drain the wine cellar at Sebastian’s ancestral castle and inventing ways to describe it. (“It’s a little shy wine like a gazelle,” “Like a leprechaun,” “and this is a wise old wine,” “A prophet in a cave.”)

Included here are passages from several contemporary novels including Rex Pickett’s poignant and hilarious Sideways, which was famously translated to the screen by Alexander Payne, but stands alone as a contemporary picaresque; along with Stephanie Danler’s coming-of-age novel Sweetbitter, with its sensuously vivid behind-the-scenes portrait of the New York restaurant world. Michael Dibdin was an English novelist who took up residence in Italy and wrote a series of literate mysteries, starring a wine-loving detective named Aurelio Zen, including A Long Finish, set in Piedmont, the home of truffles and Barolo. Also included, in its terse entirety, is one of the most memorable, and diabolical works of wine-inspired fiction—Roald Dahl’s short story “Taste.”

Food and wine are twin pleasures but too often they are divorced on the page. For years it amazed me that successive New York Times restaurant critics barely mentioned the wine list in their reviews (are you listening, Pete Wells?) and wine writing too often situates wine in a vacuum, as an independent pleasure rather than as a component of a meal. Happily that was not true of Eric Asimov, who handled the under $25 restaurant column for many years and now serves as the Times wine critic, writing about his apprenticeship to Bacchus in his memoir How to Love Wine. Some of my favorite wine commentary comes from gourmands like Richard Olney, M.F.K. Fisher, Joseph Wechsberg, and A.J. Liebling, the latter three of which are represented here. Wechsberg’s great collection Blue Trout and Black Truffles, first recommended to me by none other than Robert Parker, is an episodic memoir that traces the education of the author’s palate and his quest for Europe’s finest food and wine. Liebling’s Between Meals is one of the best books about Paris ever written, belonging on the shelf alongside Hemingway’s A Moveable Feast. Despite the title, much of the book is composed of a description of meals and his discovery of French food and wine during a student year spent in Paris, allegedly studying at the Sorbonne. He spent far more time in restaurants than in classrooms, and few eaters have written as lovingly about long-digested meals, or the wines that washed them down. Liebling was a self-professed glutton, and there’s undeniably a vicarious thrill in being privy to his excesses, like reading about Hunter Thompson’s drug intake. I’ve always imagined that Liebling would have found a kindred spirit in novelist Jim Harrison, another legendary eater and drinker who heroically pursued his culinary and oenophilic passion in spite of suffering from gout. I regret that I never broke bread or killed a bottle with Liebling, but I shared several meals, and several bottles of wine with Harrison in Paris, where we would sometimes intersect on book tours; he was passionate about both, but militantly unpretentious, and scornful of those who got too precious about their pleasures; wine geeks won’t fail to notice that he sometimes fails to note the domain and/or the vintage of some of his favorite wines.

It’s not often that someone is a good writer and a good wine importer, to paraphrase Charlotte’s Web, but two of my favorite wine books have been written by men who have made it their mission to scour Europe for artisanal wines to sell to the American drinking public. Thirty years after its publication, it’s safe to say that Kermit Lynch’s Adventures on the Wine Route is a classic. Its enduring appeal is in part a testament to the vivacity of the writing—it’s a great travel book, a chronicle of Lynch’s peregrinations through rural France, packed with vivid anecdotes and tart observations. On the one hand it conveys a sense of delighted discovery as Lynch educates his own palate and discovers buried vinous treasure in the chilly cellars of Burgundy and the Rhône and the Loire. But there is also an undertone that might be described as fiercely elegiac, as Lynch documents and laments disappearing traditions of la vieille France and deplores the onslaughts of modernity. Terry Theise’s beat is Germany and Austria, his muse the somewhat underloved Riesling grape, which he is tireless and rapturous in promoting. Theise writes better prose than most poets, and he is brilliant at evoking the way in which wine inspires the imagination. Although there is a plenty of ancillary instruction in his book Reading Between the Vines, he is scornful of the idea of over-simplifying wine appreciation. His essay “Remystifying Wine” makes a powerful case against quantifying and dumbing down what is essentially an aesthetic experience.

I like to think of this as the kind of volume to be savored while drinking a glass of Amarone, or almost any other wine that suits the reader—a book that will pair well with anything from a young Muscadet to an old Burgundy. Ideally it will inspire new thirsts.

TASTE

Roald Dahl

There were six of us to dinner that night at Mike Schofield’s house in London: Mike and his wife and daughter, my wife and I, and a man called Richard Pratt.

Richard Pratt was a famous gourmet. He was president of a small society known as the Epicures, and each month he circulated privately to its members a pamphlet on food and wines. He organized dinners where sumptuous dishes and rare wines were served. He refused to smoke for fear of harming his palate, and when discussing a wine, he had a curious, rather droll habit of referring to it as though it were a living being. “A prudent wine,” he would say, “rather diffident and evasive, but quite prudent.” Or, “a good-humoured wine, benevolent and cheerful—slightly obscene, perhaps, but nonetheless good-humoured.”

I had been to dinner at Mike’s twice before when Richard Pratt was there, and on each occasion Mike and his wife had gone out of their way to produce a special meal for the famous gourmet. And this one, clearly, was to be no exception. The moment we entered the dining room, I could see that the table was laid for a feast. The tall candles, the yellow roses, the quantity of shining silver, the three wineglasses to each person, and above all, the faint scent of roasting meat from the kitchen brought the first warm oozings of saliva to my mouth.

As we sat down, I remembered that on both Richard Pratt’s previous visits Mike had played a little betting game with him over the claret, challenging him to name its breed and its vintage. Pratt had replied that that should not be too difficult provided it was one of the great years. Mike had then bet him a case of the wine in question that he could not do it. Pratt had accepted, and had won both times. Tonight I felt sure that the little game would be played over again, for Mike was quite willing to lose the bet in order to prove that his wine was good enough to be recognized, and Pratt, for his part, seemed to take a grave, restrained pleasure in displaying his knowledge.

The meal began with a plate of whitebait, fried very crisp in butter, and to go with it there was a Moselle. Mike got up and poured the wine himself, and when he sat down again, I could see that he was watching Richard Pratt. He had set the bottle in front of me so that I could read the label. It said, “Geierslay Ohligsberg, 1945.” He leaned over and whispered to me that Geierslay was a tiny village in the Moselle, almost unknown outside Germany. He said that this wine we were drinking was something unusual, that the output of the vineyard was so small that it was almost impossible for a stranger to get any of it. He had visited Geierslay personally the previous summer in order to obtain the few dozen bottles that they had finally allowed him to have.

“I doubt anyone else in the country has any of it at the moment,” he said. I saw him glance again at Richard Pratt. “Great thing about Moselle,” he continued, raising his voice, “it’s the perfect wine to serve before a claret. A lot of people serve a Rhine wine instead, but that’s because they don’t know any better. A Rhine wine will kill a delicate claret, you know that? It’s barbaric to serve a Rhine before a claret. But a Moselle—ah!—a Moselle is exactly right.”

Mike Schofield was an amiable, middle-aged man. But he was a stock-broker. To be precise, he was a jobber in the stock market, and like a number of his kind, he seemed to be somewhat embarrassed, almost ashamed to find that he had made so much money with so slight a talent. In his heart he knew that he was not really much more than a bookmaker—an unctuous, infinitely respectable, secretly unscrupulous bookmaker—and he knew that his friends knew it, too. So he was seeking now to become a man of culture, to cultivate a literary and aesthetic taste, to collect paintings, music, books, and all the rest of it. His little sermon about Rhine wine and Moselle was a part of this thing, this culture that he sought.

“A charming little wine, don’t you think?” he said. He was still watching Richard Pratt. I could see him give a rapid furtive glance down the table each time he dropped his head to take a mouthful of whitebait. I could almost feel him waiting for the moment when Pratt would take his first sip, and look up from his glass with a smile of pleasure, of astonishment, perhaps even of wonder, and then there would be a discussion and Mike would tell him about the village of Geierslay.

But Richard Pratt did not taste his wine. He was completely engrossed in conversation with Mike’s eighteen-year-old daughter, Louise. He was half turned toward her, smiling at her, telling her, so far as I could gather, some story about a chef in a Paris restaurant. As he spoke, he leaned closer and closer to her, seeming in his eagerness almost to impinge upon her, and the poor girl leaned as far as she could away from him, nodding politely, rather desperately, and looking not at his face but at the topmost button of his dinner jacket.

We finished our fish, and the maid came around removing the plates. When she came to Pratt, she saw that he had not yet touched his food, so she hesitated, and Pratt noticed her. Her waved her away, broke off his conversation, and quickly began to eat, popping the little crisp brown fish quickly into his mouth with rapid jabbing movements of his fork. Then, when he had finished, he reached for his glass, and in two short swallows he tipped the wine down his throat and turned immediately to resume his conversation with Louise Schofield.

Mike saw it all. I was conscious of him sitting there, very still, containing himself, looking at his guest. His round jovial face seemed to loosen slightly and to sag, but he contained himself and was still and said nothing.

Soon the maid came forward with the second course. This was a large roast of beef. She placed it on the table in front of Mike who stood up and carved it, cutting the slices very thin, laying them gently on the plates for the maid to take around. When he had served everyone, including himself, he put down the carving knife and leaned forward with both hands on the edge of the table.

“Now,” he said, speaking to all of us but looking at Richard Pratt. “Now for the claret. I must go and fetch the claret, if you’ll excuse me.”

“You go and fetch it, Mike?” I said. “Where is it?”

“In my study, with the cork out—breathing.”

“Why the study?”

“Acquiring room temperature, of course. It’s been there twenty-four hours.”

“But why the study?”

“It’s the best place in the house. Richard helped me choose it last time he was here.”

At the sound of his name, Pratt looked around.

“That’s right, isn’t it?” Mike said.

“Yes,” Pratt answered, nodding gravely. “That’s right.”

“On top of the green filing cabinet in my study,” Mike said. “That’s the place we chose. A good draft-free spot in a room with an even temperature. Excuse me now, will you, while I fetch it.”

The thought of another wine to play with had restored his humor, and he hurried out the door, to return a minute later more slowly, walking softly, holding in both hands a wine basket in which a dark bottle lay. The label was out of sight, facing downward. “Now!” he cried as he came toward the table. “What about this one, Richard? You’ll never name this one!”

Richard Pratt turned slowly and looked up at Mike; then his eyes travelled down to the bottle nestling in its small wicker basket, and he raised his eyebrows, a slight, supercilious arching of the brows, and with it a pushing outward of the wet lower lip, suddenly imperious and ugly.

“You’ll never get it,” Mike said. “Not in a hundred years.”

“A claret?” Richard Pratt asked, condescending.

“Of course.”

“I assume, then, that it’s from one of the smaller vineyards?”

“Maybe it is, Richard. And then again, maybe it isn’t.”

“But it’s a good year? One of the great years?”

“Yes, I guarantee that.”

“Then it shouldn’t be too difficult,” Richard Pratt said, drawling his words, looking exceedingly bored. Except that, to me, there was something strange about his drawling and his boredom: between the eyes a shadow of something evil, and in his bearing an intentness that gave me a faint sense of uneasiness as I watched him.

“This one is really rather difficult,” Mike said, “I won’t force you to bet on this one.”

“Indeed. And why not?” Again the slow arching of the brows, the cool, intent look.

“Because it’s difficult.”

“That’s not very complimentary to me, you know.”

“My dear man,” Mike said, “I’ll bet you with pleasure, if that’s what you wish.”

“It shouldn’t be too hard to name it.”

“You mean you want to bet?”

“I’m perfectly willing to bet,” Richard Pratt said.

“All right, then, we’ll have the usual. A case of the wine itself.”

“You don’t think I’ll be able to name it, do you?”

“As a matter of fact, and with all due respect, I don’t,” Mike said. He was making some effort to remain polite, but Pratt was not bothering overmuch to conceal his contempt for the whole proceeding. And yet, curiously, his next question seemed to betray a certain interest.

“You like to increase the bet?”

“No, Richard. A case is plenty.”

“Would you like to bet fifty cases?”

“That would be silly.”

Mike stood very still behind his chair at the head of the table, carefully holding the bottle in its ridiculous wicker basket. There was a trace of whiteness around his nostrils now, and his mouth was shut very tight.

Pratt was lolling back in his chair, looking up at him, the eyebrows raised, the eyes half closed, a little smile touching the corners of his lips. And again I saw, or thought I saw, something distinctly disturbing about the man’s face, that shadow of intentness between the eyes, and in the eyes themselves, right in their centers where it was black, a small slow spark of shrewdness, hiding.

“So you don’t want to increase the bet?”

“As far as I’m concerned, old man, I don’t give a damn,” Mike said. “I’ll bet you anything you like.”

The three women and I sat quietly, watching the two men. Mike’s wife was becoming annoyed; her mouth had gone sour and I felt that at any moment she was going to interrupt. Our roast beef lay before us on our plates, slowly steaming.

“So you’ll bet me anything I like?”

“That’s what I told you. I’ll bet you anything you damn well please, if you want to make an issue out of it.”

“Even ten thousand pounds?”

“Certainly I will, if that’s the way you want it.” Mike was more confident now. He knew quite well that he could call any sum Pratt cared to mention.

“So you say I can name the bet?” Pratt asked again.

“That’s what I said.”

There was a pause while Pratt looked slowly around the table, first at me, then at the three women, each in turn. He appeared to be reminding us that we were witness to the offer.

“Mike!” Mrs. Schofield said. “Mike, why don’t we stop this nonsense and eat our food. It’s getting cold.”

“But it isn’t nonsense,” Pratt told her evenly. “We’re making a little bet.”

I noticed the maid standing in the background holding a dish of vegetables, wondering whether to come forward with them or not.

“All right, then,” Pratt said. “I’ll tell you what I want you to bet.”

“Come on, then,” Mike said, rather reckless. “I don’t give a damn what it is—you’re on.”

Pratt nodded, and again the little smile moved the corners of his lips, and then, quite slowly, looking at Mike all the time, he said, “I want you to bet me the hand of your daughter in marriage.”

Louise Schofield gave a jump. “Hey!” she cried. “No! That’s not funny! Look here, Daddy, that’s not funny at all.”

“No, dear,” her mother said. “They’re only joking.”

“I’m not joking,” Richard Pratt said.

“It’s ridiculous,” Mike said. He was off balance again now.

“You said you’d bet anything I liked.”

“I meant money.”

“You didn’t say money.”

“That’s what I meant.”

“Then it’s a pity you didn’t say it. But anyway, if you wish to go back on your offer, that’s quite all right with me.”

“It’s not a question of going back on my offer, old man. It’s a no-bet anyway, because you can’t match the stake. You yourself don’t happen to have a daughter to put up against mine in case you lose. And if you had, I wouldn’t want to marry her.”

“I’m glad of that, dear,” his wife said.

“I’ll put up anything you like,” Pratt announced. “My house, for example. How about my house?”

“Which one?” Mike asked, joking now.

“The country one.”

“Why not the other one as well?”

“All right then, if you wish it. Both my houses.”

At that point I saw Mike pause. He took a step forward and placed the bottle in its basket gently down on the table. He moved the saltcellar to one side, then the pepper, and then he picked up his knife, studied the blade thoughtfully for a moment, and put it down again. His daughter, too, had seen him pause.

“Now, Daddy!” she cried. “Don’t be absurd! It’s too silly for words. I refuse to be betted on like this.”

“Quite right, dear,” her mother said. “Stop it at once, Mike, and sit down and eat your food.”

Mike ignored her. He looked over at his daughter and he smiled, a slow, fatherly, protective smile. But in his eyes, suddenly, there glimmered a little triumph. “You know,” he said, smiling as he spoke. “You know, Louise, we ought to think about this a bit.”

“Now, stop it, Daddy! I refuse even to listen to you! Why, I’ve never heard anything so ridiculous in my life!”

“No, seriously, my dear. Just wait a moment and hear what I have to say.”

“But I don’t want to hear it.”

“Louise! Please! It’s like this. Richard here, has offered us a serious bet. He is the one who wants to make it, not me. And if he loses, he will have to hand over a considerable amount of property. Now, wait a minute, my dear, don’t interrupt. The point is this. He cannot possibly win.“

“He seems to think he can.”

“Now listen to me, because I know what I’m talking about. The expert, when tasting a claret—so long as it is not one of the famous great wines like Lafite or Latour—can only get a certain way toward naming the vineyard. He can, of course, tell you the Bordeaux district from which the wine comes, whether it is from St. Emilion, Pomerol, Graves, or Médoc. But then each district has several communes, little counties, and each county has many, many small vineyards. It is impossible for a man to differentiate between them all by taste and smell alone. I don’t mind telling you that this one I’ve got here is a wine from a small vineyard that is surrounded by many other small vineyards, and he’ll never get it. It’s impossible.”

“You can’t be sure of that,” his daughter said.

“I’m telling you I can. Though I say it myself, I understand quite a bit about this wine business, you know. And anyway, heavens alive, girl, I’m your father and you don’t think I’d let you in for—for something you didn’t want, do you? I’m trying to make you some money.”

“Mike!” his wife said sharply. “‘Stop it now, Mike, please!”

Again he ignored her. “‘If you will take this bet,” he said to his daughter, “in ten minutes you will be the owner of two large houses.”

“‘But I don’t want two large houses, Daddy.”

“Then sell them. Sell them back to him on the spot. I’ll arrange all that for you. And then, just think of it, my dear, you’ll be rich! You’ll be independent for the rest of your life!”

“Oh, Daddy, I don’t like it. I think it’s silly.”

“So do I,” the mother said. She jerked her head briskly up and down as she spoke, like a hen. “You ought to be ashamed of yourself, Michael, ever suggesting such a thing! Your own daughter, too!”

Mike didn’t even look at her. “Take it!” he said eagerly, staring hard at the girl. “Take it, quick! I’ll guarantee you won’t lose.”

“But I don’t like it, Daddy.”

“Come on, girl. Take it!”

Mike was pushing her hard. He was leaning toward her, fixing her with two hard bright eyes, and it was not easy for the daughter to resist him.

“But what if I lose?”

“I keep telling you, you can’t lose. I’ll guarantee it.”

“Oh, Daddy, must I?”

“I’m making you a fortune. So come on now. What do you say, Louise? All right?”

For the last time, she hesitated. Then she gave a helpless little shrug of the shoulders and said, “Oh, all right, then. Just so long as you swear there’s no danger of losing.”

“Good!” Mike cried. “That’s fine! Then it’s a bet!”

“Yes,” Richard Pratt said, looking at the girl. “It’s a bet.”

Immediately, Mike picked up the wine, tipped the first thimbleful into his own glass, then skipped excitedly around the table filling up the others. Now everyone was watching Richard Pratt, watching his face as he reached slowly for his glass with his right hand and lifted it to his nose. The man was about fifty years old and he did not have a pleasant face. Somehow, it was all mouth—mouth and lips—the full, wet lips of the professional gourmet, the lower lip hanging downward in the center, a pendulous, permanently open taster’s lip, shaped open to receive the rim of a glass or a morsel of food. Like a keyhole, I thought, watching it; his mouth is like a large wet keyhole.

Slowly he lifted the glass to his nose. The point of the nose entered the glass and moved over the surface of the wine, delicately sniffing. He swirled the wine gently around in the glass to receive the bouquet. His concentration was intense. He had closed his eyes, and now the whole top half of his body, the head and neck and chest, seemed to become a kind of huge sensitive smelling-machine, receiving, filtering, analysing the message from the sniffing nose.

Mike, I noticed, was lounging in his chair, apparently unconcerned, but he was watching every move. Mrs. Schofield, the wife, sat prim and upright at the other end of the table, looking straight ahead, her face tight with disapproval. The daughter, Louise, had shifted her chair away a little, and sidewise, facing the gourmet, and she, like her father, was watching closely.

For at least a minute, the smelling process continued; then, without opening his eyes or moving his head, Pratt lowered the glass to his mouth and tipped in almost half the contents. He paused, his mouth full of wine, getting the first taste; then he permitted some of it to trickle down his throat and I saw his Adam’s apple move as it passed by. But most of it he retained in his mouth. And now, without swallowing again, he drew in through his lips a thin breath of air which mingled with the fumes of the wine in the mouth and passed on down into his lungs. He held the breath, blew it out through his nose, and finally began to roll the wine around under the tongue, and chewed it, actually chewed it with his teeth as though it were bread.

It was a solemn, impressive performance, and I must say he did it well.

“Um,” he said, putting down the glass, running a pink tongue over his lips. “Um—yes. A very interesting little wine—gentle and gracious, almost feminine in the aftertaste.”

There was an excess of saliva in his mouth, and as he spoke he spat an occasional bright speck of it onto the table.

“Now we can start to eliminate,” he said. “You will pardon me for doing this carefully, but there is much at stake. Normally I would perhaps take a bit of a chance, leaping forward quickly and landing right in the middle of the vineyard of my choice. But this time—I must move cautiously this time, must I not?” He looked up at Mike and he smiled, a thick-lipped, wet-lipped smile. Mike did not smile back.

“First, then, which district in Bordeaux does this wine come from? That is not too difficult to guess. It is far too light in the body to be from either St. Emilion or Graves. It is obviously a Médoc. There’s no doubt about that.

“Now—from which commune in Médoc does it come? That also, by elimination, should not be too difficult to decide. Margaux? No. It cannot be Margaux. It has not the violent bouquet of a Margaux. Pauillac? It cannot be Pauillac, either. It is too tender, too gentle and wistful for a Pauillac. The wine of Pauillac has a character that is almost imperious in its taste. And also, to me, a Pauillac contains just a little pith, a curious, dusty, pithy flavor that the grape acquires from the soil of the district. No, no. This—this is a very gentle wine, demure and bashful in the first taste, emerging shyly but quite graciously in the second. A little arch, perhaps, in the second taste, and a little naughty also, teasing the tongue with a trace, just a trace, of tannin. Then, in the aftertaste, delightful—consoling and feminine, with a certain blithely generous quality that one associates only with the wines of the commune of St. Julien. Unmistakably this is a St. Julien.”

He leaned back in his chair, held his hands up level with his chest, and placed the fingertips carefully together. He was becoming ridiculously pompous, but I thought that some of it was deliberate, simply to mock his host. I found myself waiting rather tensely for him to go on. The girl Louise was lighting a cigarette. Pratt heard the match strike and he turned on her, flaring suddenly with real anger. “Please!” he said. “Please don’t do that! It’s a disgusting habit, to smoke at table!”

She looked up at him, still holding the burning match in one hand, the big slow eyes settling on his face, resting there a moment, moving away again, slow and contemptuous. She bent her head and blew out the match, but continued to hold the unlighted cigarette in her fingers.

“I’m sorry, my dear,” Pratt said, “but I simply cannot have smoking at table.”

She didn’t look at him again.

“Now, let me see—where were we?” he said. “Ah, yes. This wine is from Bordeaux, from the commune of St. Julien, in the district of Médoc. So far, so good. But now we come to the more difficult part—the name of the vineyard itself. For in St. Julien there are many vineyards, and as our host so rightly remarked earlier on, there is often not much difference between the wine of one and the wine of another. But we shall see.”

He paused again, closing his eyes. “I am trying to establish the ‘growth,’“ he said. “If I can do that, it will be half the battle. Now, let me see. This wine is obviously not from a first-growth vineyard—nor even a second. It is not a great wine. The quality, the—the—what do you call it?—the radiance, the power, is lacking. But a third growth—that it could be. And yet I doubt it. We know it is a good year—our host has said so—and this is probably flattering it a little bit. I must be careful. I must be very careful here.”

He picked up his glass and took another small sip.

“Yes,” he said, sucking his lips, “I was right. It is a fourth growth. Now I am sure of it. A fourth growth from a very good year—from a great year, in fact. And that’s what made it taste for a moment like a third—or even a second-growth wine. Good! That’s better! Now we are closing in! What are the fourth-growth vineyards in the commune of St. Julien?”

Again he paused, took up his glass, and held the rim against that sagging, pendulous lower lip of his. Then I saw the tongue shoot out, pink and narrow, the tip of it dipping into the wine, withdrawing swiftly again—a repulsive sight. When he lowered the glass, his eyes remained closed, the face concentrated, only the lips moving, sliding over each other like two pieces of wet, spongy rubber.

“There it is again!” he cried. “Tannin in the middle taste, and the quick astringent squeeze upon the tongue. Yes, yes, of course! Now I have it! This wine comes from one of those small vineyards around Beychevelle. I remember now. The Beychevelle district, and the river and the little harbor that has silted up so the wine ships can no longer use it. Beychevelle … could it actually be a Beychevelle itself? No, I don’t think so. Not quite. But it is somewhere very close. Château Talbot? Could it be Talbot? Yes, it could. Wait one moment.”

He sipped the wine again, and out of the side of my eye I noticed Mike Schofield and how he was leaning farther and farther forward over the table, his mouth slightly open, his small eyes fixed upon Richard Pratt.

“No. I was wrong. It was not a Talbot. A Talbot comes forward to you just a little quicker than this one; the fruit is nearer to the surface. If it is a ‘34, which I believe it is, then it couldn’t be Talbot. Well, well. Let me think. It is not a Beychevelle and it is not a Talbot, and yet—yet it is so close to both of them, so close, that the vineyard must be almost in between. Now, which could that be?”

He hesitated, and we waited, watching his face. Everyone, even Mike’s wife, was watching him now. I heard the maid put down the dish of vegetables on the sideboard behind me, gently, so as not to disturb the silence.

“Ah!” he cried. “I have it! Yes, I think I have it!”

For the last time, he sipped the wine. Then, still holding the glass up near his mouth, he turned to Mike and he smiled, a slow, silky smile, and he said, “‘You know what this is? This is the little Château Branaire-Ducru.”

Mike sat tight, not moving.

“And the year, 1934.”

We all looked at Mike, waiting for him to turn the bottle around in its basket and show the label.

“Is that your final answer?” Mike said.

“Yes, I think so.”

“Well, is it or isn’t it?”

“Yes, it is.”

“What was the name again?”

“Château Branaire-Ducru. Pretty little vineyard. Lovely old château. Know it quite well. Can’t think why I didn’t recognize it at once.”

“Come on, Daddy,” the girl said. “Turn it round and let’s have a peek. I want my two houses.”

“Just a minute,” Mike said. “Wait just a minute.” He was sitting very quiet, bewildered-looking, and his face was becoming puffy and pale, as though all the force was draining slowly out of him.

“Michael!” his wife called sharply from the other end of the table. “What’s the matter?”

“Keep out of this, Margaret, will you please.”

Richard Pratt was looking at Mike, smiling with his mouth, his eyes small and bright. Mike was not looking at anyone.

“Daddy!” the daughter cried, agonized. “But, Daddy, you don’t mean to say he’s guessed it right!”

“Now, stop worrying, my dear,” Mike said. “There’s nothing to worry about.”

I think it was more to get away from his family than anything else that Mike then turned to Richard Pratt and said, “I’ll tell you what, Richard. I think you and I better slip off into the next room and have a little chat?”

“I don’t want a little chat,” Pratt said. “All I want is to see the label on that bottle.” He knew he was a winner now; he had the bearing, the quiet arrogance of a winner, and I could see that he was prepared to become thoroughly nasty if there was any trouble. “What are you waiting for?” he said to Mike. “Go on and turn it round.”

Then this happened: The maid, the tiny, erect figure of the maid in her white-and-black uniform, was standing beside Richard Pratt, holding something out in her hand. “I believe these are yours, sir,” she said.

Pratt glanced around, saw the pair of thin horn-rimmed spectacles that she held out to him, and for a moment he hesitated. “Are they? Perhaps they are. I don’t know.”

“Yes sir, they’re yours.” The maid was an elderly woman—nearer seventy than sixty—a faithful family retainer of many years’ standing. She put the spectacles down on the table beside him.

Without thanking her, Pratt took them up and slipped them into his top pocket, behind the white handkerchief.

But the maid didn’t go away. She remained standing beside and slightly behind Richard Pratt, and there was something so unusual in her manner and in the way she stood there, small, motionless, and erect, that I for one found myself watching her with a sudden apprehension. Her old gray face had a frosty, determined look, the lips were compressed, the little chin was out, and the hands were clasped together tight before her. The curious cap on her head and the flash of white down the front of her uniform made her seem like some tiny, ruffled, white-breasted bird.

“You left them in Mr. Scofield’s study,” she said. Her voice was unnaturally, deliberately polite. “On top of the green filing cabinet in his study, sir, when you happened to go in there by yourself before dinner.”

It took a few moments for the full meaning of her words to penetrate, and in the silence that followed I became aware of Mike and how he was slowly drawing himself up in his chair, and the color coming to his face, and the eyes opening wide, and the curl of the mouth, and the dangerous little patch of whiteness beginning to spread around the area of the nostrils.

“Now, Michael!” his wife said. “Keep calm now, Michael, dear! Keep calm!”

A STUNNING UPSET

George Taber

A bottle of good wine, like a good act, shines ever in the retrospect.

—Robert Louis Stevenson

May 24, 1976, was a beautiful, sunny day in Paris, and Patricia Gallagher was in good spirits as she packed up the French and California wines for the tasting at the lnterContinental Hotel. Organizing the event had been good fun and easy compared with other events she and Steven had dreamed up. The good thing about working for Spurrier, she told friends, was that he was so supportive of her ideas. Many of their conversations began with her saying, “Wouldn’t it be fun …” To which he always replied, “Great. Let’s do it.” The two weren’t looking for fame or money. They were young people doing things strictly for the love of wine and to have fun.

Gallagher packed the wine and all the paperwork into the back of the Caves de la Madeleine’s van and headed off with an American summer intern to the hotel. After the California wines had arrived on May 7 with members of the Tchelistcheff tour, they were stored in the shop’s cellar at a constant 54 degrees alongside the French wines for the event and the rest of Spurrier’s stock.

Gallagher and the intern arrived at the hotel about an hour and a half before the 3:00 p.m. tasting was due to start. The event was to be held in a well-appointed room just off a patio bar in the central courtyard. Long, plush velvet curtains decorated the corners of the room. Glass doors opened onto the patio, and a gathering crowd watched the event from the patio. People sitting at small tables under umbrellas became increasingly curious about what was transpiring in the room, and some of them walked over to gaze through the windows much like visitors looking at monkeys in a zoo. The waiters set up a series of plain tables covered with simple white tablecloths, aligning the tables in a long row.

Spurrier and Gallagher had previously decided that this would be a blind tasting, which meant that the judges would not see the labels on the bottles, a common practice in such events. They felt that not allowing the judges to know the nationality or brand of the wines would force them to be more objective. The two did not perceive the tasting as a Franco-American showdown, but it would have been too easy, they believed, for the judges to find fault with the California wines while praising only the French wines, if they were presented with labels.

The hotel staff first opened all the red wines and then poured them into neutral bottles at Gallagher’s instructions. California wine bottles are shaped slightly differently from French ones, and this group of knowledgeable judges would have quickly recognized the difference. Gallagher was also giving the wines a chance to breathe a little by opening and decanting them, since the reds, in particular, were still relatively recent vintages. This practice helps young wines, which can sometimes be too aggressive, become more mellow and agreeable.

An hour before the event, the hotel staff opened all the white wines, poured them also into neutral bottles and put them in the hotel’s wine cooler. Aeration was less important for the whites than it had been for the reds, but it would do no harm to have them opened in advance. Then a few minutes before the tasting, the waiters put the whites in buckets on ice, just as they would have done for guests in the dining room. The wine would now be at the perfect temperature for the judges.

Only a half-hour before the event was to begin, Spurrier arrived. He wrote the names of the wines on small pieces of paper and asked the summer intern to pull the names out of a hat to determine the order in which the wines would be served. Then Spurrier and the others put small white labels on the bottles that read in French, for example, Chardonnay Neuf (Chardonnay Nine) or Cabernet Trois (Cabernet Three). With that done, everything was ready.

The judges began appearing shortly before 3:00 p.m. and chatted amiably until all had arrived. Most of them knew each other from many previous encounters on the French wine circuit.

Standing along the wall and acting self-conscious were two young Frenchmen in their mid-twenties. One was Jean-Pierre Leroux, who was head of the dining room at the Paris Sofitel hotel, an elegant rival, although not at the same level as the lnterContinental. The other was Gérard Bosseau des Chouad, the sommelier at the Sofitel, who had learned about the tasting while taking a course at the Académie du Vin. Bosseau des Chouad had told Leroux about it, and the two of them had come to the hotel uninvited on a lark. They were quiet in awe of the assembled big names of French wine and cuisine. Since no one asked them to leave, they watched the proceedings in nervous silence.

Shortly after 3:00, Spurrier asked everyone to give him their attention for a minute. Spurrier thanked the judges for coming and explained that he and Patricia Gallagher were staging the event to taste some of the interesting new California wines as part of the bicentennial of American independence and in honor of the role France had played in that historic endeavor. He explained that he and Patricia had recently made separate trips to California, where they had been surprised by the quality of the work being done by some small and unknown wineries. He said he thought the French too would find them interesting. Spurrier then said that although he had invited them to a sampling of California wines, in the tasting that was about to begin he had also included some very similar French wines. He added that he thought it would be better if they all tasted them blind, so as to be totally objective in their judgments. No one demurred, and so judges took their seats behind the long table, and the event began.

The judges wore standard Paris business attire. Odette Kahn of the Revue du Vin de France was very elegant in a patterned silk dress accented with a double strand of opera-length pearls. Claude Dubois-Millot was the most casual with no tie or jacket. The other men were all more formally dressed, and Aubert de Villaine, who sat at the far right end of the table, wore a fashionable double-breasted suit. Patricia Gallagher and Steven Spurrier sat in the middle of the judges and participated in the tasting. Spurrier was next to Kahn.

In front of each judge was a scorecard and pencil, two stemmed wine glasses, and a small roll. Behind them were several Champagne buckets on stands where they could spit the wine after tasting it, a common practice at such events since it would be impossible to drink all the wines without soon feeling the effect of the alcohol.

Spurrier instructed the judges that they were being asked to rank the wines by four criteria—eye, nose, mouth, and harmony—and then to give each a score on the basis of 20 points. Eye meant rating the color and clarity of the wine; nose was the aroma; mouth was the wine’s taste and structure as it rolled over the taste buds; harmony meant the combination of all the sensations. This 20-point and four-criteria system was common in France at the time and had already been used by Spurrier and the others in many tastings.

Despite Spurrier’s and Gallagher’s attempts to get press coverage, it turned out that I was the only journalist who showed up at the event. As a result, I had easy access to the judges and the judging. Patricia gave me a list of the wines with the tasting order so I could follow along. And although the judges didn’t know the identity of Chardonnay Neuf, for example, I did and could note their reactions to the various wines as they tasted them.

The waiters first poured a glass of 1974 Chablis to freshen the palates of the judges. Following the tradition of wine tastings, the whites then went first. I looked at my list of wines and saw that the first wine (Chardonnay Un) was the Puligny-Montrachet Les Pucelles Domaine Leflaive, 1972.

The nine judges seemed nervous at the beginning. There was lots of laughing and quick side comments. No one, though, was acting rashly. The judges pondered the wines carefully and made their judgments slowly. Pierre Tari at one moment pushed his nose deep into his glass and held it there for a long time to savor the wine’s aroma.

The judge’s comments were in the orchidaceous language the French often use to describe wines. As I stood only a few feet from the judges listening to their commentary, I copied into the brown reporter’s notebook that I always carried with me such phrases as: “This soars out of the ordinary,” and “A good nose, but not too much in the mouth,” and “This is nervous and agreeable.”

From their comments, though, I soon realized that the judges were becoming totally confused as they tasted the white wines. The panel couldn’t tell the difference between the French ones and those from California. The judges then began talking to each other, which is very rare in a tasting. They speculated about a wine’s nationality, often disagreeing.

Standing quietly on the side, the young Jean-Pierre Leroux was also surprised as he looked at the faces of the judges. They seemed both bewildered and shocked, as if they didn’t quite know what was happening. Raymond Oliver of the Grand Véfour was one of Leroux’s heroes, and the young man couldn’t believe that the famous chef couldn’t distinguish the nationality of the white wines.

Christian Vannequé, who sat at the far left with Pierre Bréjoux and Pierre Tari at his left, was irritated that those two kept talking to him, asking him what he thought of this or that wine. Vannequé felt like telling them to shut up so he could concentrate, but held his tongue. He thought the other judges seemed tense and were trying too hard to identify which wines were Californian and which were French. Vannequé complained he wanted simply to determine which wines were best.

When tasting the white wines, the judges quickly became flustered. At one point Raymond Oliver was certain he had just sipped a French wine, when in fact it was a California one from Freemark Abbey. Shortly after, Claude Dubois-Millot said he thought a wine was obviously from California because it had no nose, when it was France’s famed Bâtard-Montrachet.

The judges were brutal when they found a wine wanting. They completely dismissed the David Bruce Chardonnay. Pierre Bréjoux gave it 0 points out of 20. Odette Kahn gave it just 1 point. The David Bruce was rated last by all the judges, and most of them dumped the remains from their glasses into their Champagne buckets after a cursory taste and in some cases after only smelling it. Robert Finigan had warned Spurrier and Gallagher that he’d found David Bruce wines at that time could be erratic, and this bottle appeared to be erratically bad. It was probably spoiled.

After the white wines had all been tasted, Spurrier called a break and collected the scorecards. Using the normal procedure for wine tastings, he added up the individual scores and then ranked them from highest to lowest.

Meanwhile the waiters began pouring Vittel mineral water for the judges to drink during the break. The judges spoke quietly to each other, and I talked briefly with Dubois-Millot. Even though he did not yet know the results, he told me a bit sheepishly, “We thought we were recognizing French wines, when they were California and vice versa. At times we’d say that a wine would be thin and therefore California, when it wasn’t. Our confusion showed how good California wines have become.”

Spurrier’s original plan had been to announce all the results at the end of the day, but the waiters were slow clearing the tables and getting the red wines together and the program was getting badly behind schedule, so he decided to give the results of the white-wine tasting. He had been personally stunned and began reading them slowly to the group:

1. Chateau Montelena 1973

2. Meursault Charmes 1973

3. Chalone 1974

4. Spring Mountain 1973

5. Beaune Clos des Mouches 1973

6. Freemark Abbey 1972

7. Bâtard-Montrachet 1973

8. Puligny-Montrachet 1972

9. Veedercrest 1972

10. David Bruce 1973

When he finished, Spurrier looked at the judges, whose reaction ranged from shock to horror. No one had expected this, and soon the whole room was abuzz.

After hearing the results, I walked up to Gallagher. The French word in the winning wine’s name had momentarily thrown me. “Chateau Montelena is Californian, isn’t it?” I asked a bit dumbfoundedly.

“Yes, it is,” she replied calmly.

The scores of the individual judges made the results even more astounding. California Chardonnays had overwhelmed their French counterparts. Every single French judge rated a California Chardonnay first. Chateau Montelena was given top rating by six judges; Chalone was rated first by the other three. Three of the top four wines were Californian. Claude Dubois-Millot gave Chateau Montelena 18.5 out of 20 points, while Aubert de Villaine gave it 18. Chateau Montelena scored a total of 132 points, comfortably ahead of second place Meursault Charmes, which got 126.5.

Spurrier and Gallagher, who were also blind tasting the wines although their scores were not counted in the final tally, were tougher on the California wines than the French judges. Spurrier had a tie for first between Freemark Abbey and Bâtard-Montrachet, while Gallagher scored a tie for first between Meursault Charmes and Spring Mountain.

As I watched the reaction of the others to the results, I felt a sense of both awe and pride. Who would have thought it? Chauvinism is a word invented by the French, but I felt some chauvinism that a California white wine had won. But how could this be happening? I was tempted to ask for a taste of the winning California Chardonnay, but decided against it. I still had a reporting job to finish, and I needed to have a clear head.

As the waiters began pouring the reds, Spurrier was certain that the judges would be more careful and would not allow a California wine to come out on top again. One California wine winning was bad enough; two would be treason. The French judges, he felt, would be very careful to identify the French wines and score them high, while rating those that seemed American low. It would perhaps be easier to taste the differences between the two since the judges knew all the French wines very well. The French reds, with their classic, distinctive and familiar tastes would certainly stand out against the California reds. All the judges, with the possible exception of Dubois-Millot, had probably tasted the French reds hundreds of times.

There was less chatter during the second wave of wines. The judges seemed both more intense and more circumspect. Their comments about the nationality of the wine in their glass were now usually correct. “That’s a California, or I don’t know what I’m doing here,” said Christian Vannequé of La Tour d’Argent. I looked at my card and saw that he was right. It was the Ridge Monte Bello.

Raymond Oliver took one quick sip of a red and proclaimed, “That’s a Mouton, without a doubt.” He too was right.

Because of delays in the earlier part of the tasting, the hour was getting late and the group had to be out by 6:00 p.m. So Spurrier pushed on quickly after the ballots were collected. He followed the same procedure he had used for the Chardonnay tasting, adding up the individual scores of the nine judges.

The room was hushed as Spurrier read the results without the help of a microphone:

1. Stag’s Leap Wine Cellars 1973

2. Château Mouton Rothschild 1970

3. Château Montrose 1970

4. Château Haut-Brion 1970

5. Ridge Monte Bello 1971