17,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: John Wiley & Sons

- Kategorie: Fachliteratur

- Sprache: Englisch

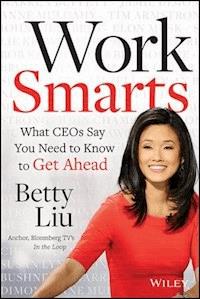

Award-winning Bloomberg television host Betty Liu compiles the wisdom of the world's best CEOs into a fun, insightful, and practical guide for success. Betty Liu is famous the world over for asking the tough questions of today's most successful people--and for her uncanny ability to get straight answers where others have failed. As an award-winning financial journalist and Bloomberg Television anchor, Betty has sat down with billionaires, CEOs, politicians, and celebrities to get their views from the top. Now, in Work Smarts, Betty helps you get to the top by distilling the wisdom of some of the most prominent CEOs in the country. Warren Buffett, Jamie Dimon, Elon Musk, Sam Zell, John Chambers, Anne Mulcahy, and many more spill the beans on what it really takes to be successful, giving practical, "from the street" advice on how to get ahead in your career. Packed with candid, often humorous, revelations from leaders in the world of finance, technology, retail, telecom, entertainment, and more, Work Smarts delivers priceless guidance on: * How to really network * The importance of being likable * What your boss is thinking when you ask for a raise * Winning every negotiation * Bouncing back from a firing or layoff * Thinking like a true entrepreneur * The secret skill every successful person needs * Overcoming fear * Being a standout job candidate * Knowing what's holding you back * Knowing what can propel you forward * Why sometimes being good at your job just isn't enough Combining the trademark, hands-on approach of one of today's most respected financial journalists with the wisdom of the world's most successful business leaders, Work Smarts is a gold mine of real-world insight and advice on how to get ahead in business and forge a career that maximizes all your best talents and skills.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 328

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Ähnliche

Contents

Introduction

Part One: If I Knew This Before, I’d Be a Millionaire. . .

Chapter 1: The Company of One

Chapter 2: Why the Q Factor Is So Important

Chapter 3: How to Network

Chapter 4: Asking for a Raise

Part Two: The Three Fs: Fear, Finances, and Flow

Chapter 5: The Art of Negotiation

Chapter 6: Fear

Chapter 7: Finances

Chapter 8: Flow

Part Three: Postcards from the C-Suite

Chapter 9: What It’s Really Like to Be a CEO

Chapter 10: Sound Off: The Most Annoying . . .

Part Four: Things I’ve Learned

Chapter 11: You Can’t Really Be Good at Everything . . . and That’s OK!

Chapter 12: Five Tips for Life

Bibliography

About the Author

Index

Cover image: Dave Cross Photography, Inc.

Cover design: C. Wallace

Copyright © 2014 by Betty Liu. All rights reserved.

Published by John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken, New Jersey.

Published simultaneously in Canada.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning, or otherwise, except as permitted under Section 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without either the prior written permission of the Publisher, or authorization through payment of the appropriate per-copy fee to the Copyright Clearance Center, Inc., 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, (978) 750-8400, fax (978) 646-8600, or on the Web at www.copyright.com. Requests to the Publisher for permission should be addressed to the Permissions Department, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 111 River Street, Hoboken, NJ 07030, (201) 748-6011, fax (201) 748-6008, or online at http://www.wiley.com/go/permissions.

Limit of Liability/Disclaimer of Warranty: While the publisher and author have used their best efforts in preparing this book, they make no representations or warranties with respect to the accuracy or completeness of the contents of this book and specifically disclaim any implied warranties of merchantability or fitness for a particular purpose. No warranty may be created or extended by sales representatives or written sales materials. The advice and strategies contained herein may not be suitable for your situation. You should consult with a professional where appropriate. Neither the publisher nor author shall be liable for any loss of profit or any other commercial damages, including but not limited to special, incidental, consequential, or other damages.

For general information on our other products and services or for technical support, please contact our Customer Care Department within the United States at (800) 762-2974, outside the United States at (317) 572-3993, or fax (317) 572-4002.

Wiley publishes in a variety of print and electronic formats and by print-on-demand. Some material included with standard print versions of this book may not be included in e-books or in print-on-demand. If this book refers to media such as a CD or DVD that is not included in the version you purchased, you may download this material at http://booksupport.wiley.com. For more information about Wiley products, visit www.wiley.com.

ISBN 978-1-118-74467-3 (Hardcover)

ISBN 978-1-118-74798-8 (ePDF)

ISBN 978-1-118-74493-2 (ePub)

Even if you’re on the right track, you’ll get run over if you just sit there.

—Will Rogers

Introduction

You’ve just graduated college . . .

You want to get to a promotion . . .

. . . or you’ve just been laid off.

Whatever the case, you’re looking for some advice. Real advice. What does it really take to succeed? How do you get started? How do you pick yourself back up if you’ve fallen? What if I need to jump-start my career and it’s not enough that my spouse or mother is telling me I’m the greatest person in the world. That’s not actually getting me to my goal. I need real advice “from the street,” so to speak.

If you feel any of the above, this book is for you.

It’s also a book for me.

I interview people for a living who are at the top of their careers: CEOs, economists, policy thinkers, entrepreneurs. Inevitably, I began to wonder, how did they get there? Why can’t we get beyond the follow-your-passion advice and really find out what it takes to forge a career that maximizes all your interests and skills. What holds people back? What gets them ahead?

No career is perfect. Mine is riddled with mistakes and rejections. That’s why I had in the back of my mind that this book is also written for me. Have you ever lain awake at night, rehashing a conversation or a meeting? Yep, that’s me. Maybe I didn’t convey what I wanted to in the right way, I think. “I shoulda” and “I coulda” are common phrases that pop in my head. When I head into the boss’ office to pitch an idea, I fret about it beforehand. How do I say it right? Surely, I think, others go through this too. How do they find the advice?

There’s a joke that there are more therapists in Manhattan than police. If you widened that out, according to data extrapolated from the International Coaching Federation, there’s now about one life coach for every 3,200 people in the United States. A decade ago, who even heard of a life coach? Clearly, people are looking for guidance, especially when they keep hearing about a jobs market that’s scarily getting smaller and tougher.

About 9 million people lost their jobs during the latest recession that began in 2007. As of this writing, things have improved. Firings are at their lowest level in five years and job openings are, conversely, at the highest level in five years. But the situation is a lot tougher. Some jobs in manufacturing, autos, and finance may never come back. Our salaries have pretty much gone nowhere in the last 10 years, which means we’ve got less money to spend because prices keep going up. And while the jobs are coming back, a good number of them are part-time or lower paying jobs which helps bring down the jobless rate, but doesn’t do much in the great scheme of getting ahead.

Okay, I’m not trying to depress you. I’m just giving you a reality check. Many people bury their heads in the sand when it comes to their careers. They hope things will just work out. But careers are not a lottery ticket—they’re not made out of luck. One CEO told me one of his biggest regrets is not managing his career better when he was younger. And this is coming from someone who is now a multi-millionaire with his own business. He says the biggest mistake he sees others make is that people are too passive about their careers. I’m a big believer in “everything happens for a reason,” but at the least, you want to make sure you’re doing everything you can to put the odds in your favor.

I’m not only talking about big ideas like: “How do I start my own business?” I’m talking about the small things that add up to a successful career:

Men and women both have problems with the above. Around the time I was writing and researching, Sheryl Sandberg’s book Lean In sparked a national debate about equality of women in the workplace. I was glad to see all the attention the Facebook chief operating officer brought to the topic but I also felt the impression was that women did everything wrong in the workplace. The fact is, both men and women commit similar blunders. Both feel deficient in many of the topics Sheryl pointed out—networking, mentorship, salaries. I have a male friend who constantly complains he is not well paid. The problem is not his gender but because he’s just not very good at asking for a raise.

So if you want to know what’s the best way to do this, read this book. If you’ve ever wanted to get inside a boss’ head, this is as close as you’ll get. If you’re curious to know how the best in business got where they are, read on. If you want to know how even the most successful CEOs out there made mistakes and got fired, that’s all in this book, too. Take your head out of the sand and go out there with your eyes wide open and only good will come out of it.

********

People ask me all the time how I got into television.

The reason why they ask is because I got into television mid-career. I made the switch at the worst possible time, when I had left my job to have children. Not only was I leaving my current job but I was also attempting to get into a new, competitive career after having kids.

I learned two very valuable lessons in my career switch.

One came from a television coach who taught me something that had nothing to do with television. Let me explain.

A television agent said to me (years before I actually left my job) that if I had any serious thoughts about trying my hand at on-air work, I would need to hire a talent coach. So on her recommendation, I found one in New York. It was just a one-day session held at this person’s office. Or at least, I think it was her office. It may have been one of those rented spaces that give small businesses the air of a real office.

She walked over and led me into a little white room where several newspapers were laid out. Over the next hour or so, she had me read the newspapers as if they were television scripts. “More energy and emphasis!” she guided. After dozens of reads, I was starting to tune out. How many different ways can I read these paragraphs, I thought. Where I thought I was conveying energy, she was telling me I sounded flat. What was I really trying to accomplish? I just wanted to report good stories; I kept asking myself, why did I need to learn to read? She started getting on my nerves. I started not to like her hair. I wondered if her methods worked. I began to think about her fee. Everything else entered my head except that I needed to focus on being better to get a job.

Sensing my animosity, she suddenly sat down.

“I know this is frustrating,” she said. “I’m trying to help you find a job. You’re getting mad at me but you’re really mad at the process. It’s scary out there. Everyone wants to do the same thing you’re doing.”

She got up and grabbed a black marker and scribbled on the whiteboard.

Opportunity + Preparation = Luck

“Betty, do you understand what this means?”

“Yes, I do,” I said flatly.

“No, do you really understand what this means?”

I stared at her for a moment.

“People see other’s successes and they think, oh, they’re just lucky. Nobody is ever lucky, trust me. Sure, things happen to people. There’s stories everywhere of people who’ve been toiling away and all of a sudden, they get the dream job they’ve always wanted; or their business idea suddenly takes off and they make millions. We look at that and think, they’re lucky. No honey, they’re not lucky. They were prepared.

“Opportunities are everywhere for people. But if you’re not prepared, then you won’t be able to capitalize on that opportunity. It’s not luck, it’s being prepared. It’s doing the really hard work of being prepared for the one day when you get that opportunity. It may only come once so you have to be prepared. Your job is to prepare your whole life for that opportunity. Do you understand what I’m saying?”

She leaned in. “Do you understand?”

I hadn’t thought I was buying a life lesson but there it was, staring me in the face.

At that point, it really did sink in.

Richard Wiseman is a researcher in the UK who explores the idea of luck. In his fascinating 2003 book The Luck Factor, he concocted an experiment to show how “lucky” and “unlucky” people behave.

In one, he taped a five-pound British note on the ground outside a coffee shop near his office. He asked his test subjects, Brenda and Martin, to meet someone involved in a research project at the cafe. Martin considered himself a lucky man. Brenda thought she was an unlucky person. The scheming professor put various people in the coffee shop including a “millionaire” who was to do exactly the same thing with Brenda as he would with Martin.

Can you guess what happened?

Martin spotted the money right away on the ground, picked it up, and walked into the coffee shop. He sat next to the “millionaire” and began chatting him up, even buying him a coffee with the extra money he found. They began a fruitful dialogue and discussed connecting again on possible projects. Brenda, in the meantime, walked right past the free money, bought her coffee, and also sat down next to the millionaire. But she didn’t talk to him and he was instructed not to approach her first. So she left with no interaction and no extra money.

Imagine this was a real life scenario and you can easily see how one set of behaviors could lead to a lucky break and the other would lead to nothing. How many millionaires have you walked by and not said a word?

Me, personally, I really don’t like the word lucky. I prefer “optimism.” The people featured in this book are generally resilient optimists. They’re always preparing for the next chance that could change their futures. In certain cases, a no means a no, but in this instance, when it comes to your career, a no means you’ve got to look for another avenue to a yes.

After that day with the talent coach I stopped deluding myself that if I didn’t get a job in television it was because I was unlucky. I went about practicing and preparing and keeping my ears and eyes peeled for any opportunities or chance connections. I wasn’t nutty about it but just conscious that this was my goal and I was going to somehow get to it one way or the other.

Which led me to the other valuable lesson I learned in this transition.

Persistence does pay off.

It would be a nicely tied story if I said I got my job in television a few months later.

No, I had much longer to go. I spent many years after with other coaches. I auditioned for several jobs with nothing. Lots of people were more than happy to tell me I had no future in television. I remember one executive producer who said he had a good gut sense of who had innate talent for television and he didn’t see it in me. I heard a few years later he got laid off.

To learn the art of scriptwriting, I joined a public radio station. I knew it would teach me how to write differently and to really understand what on-air reading was like. I didn’t get paid and I didn’t care. What they were teaching me was far more valuable. I put together a professional demo tape. I spent many hours and lots of money getting it just right. The tape editors I worked with were all freelance guys who were very nice, but eager to go on about how ruthless television was and that people end up getting fired and tossed out like yesterday’s garbage. There was a lot of tuning out during this time. If I listened to all the negativity, I would have given up pretty quickly.

Years later, when I could have been written off, on maternity leave, and with no job to come back to, I got the call. The head of CNBC Asia, a woman who I had met years earlier and who did not hire me then, said she finally had a job opening and thought of me. I don’t know why she thought of me, but she did. I had the right background. She seemed to like me. I kept in touch with her through the years with an occasional e-mail.

A few months later, I was packing my bags and heading back to Hong Kong in my first on-air television job. I was nervous, excited, and scared but also grateful. I was glad she didn’t hire me back then. I wasn’t prepared and she knew it. I was ready now. Later, whenever friends said to me, you’re so lucky you got that job, I would think, you don’t even know the half of it.

I don’t even remember this television coach’s name—or her face. I’m sure if I really tried, I could track her down. But I like having what she taught me hang nameless, like a broad script in the sky. She set me on that path of preparation and I learned persistence.

So if you still think a successful career is much about luck, stop reading. If not, read ahead so you can be prepared.

Part One

If I Knew This Before, I’d Be a Millionaire. . .

Chapter 1

The Company of One

Glenn Hutchins talks really fast. He’s also really tall.

The combination of the two means he’s good at making a deal and he could have played basketball.

So when Glenn made his riches in private equity, he bought a stake in a basketball team, the Boston Celtics. Glenn graduated from Harvard and began his career on Wall Street as a junior analyst at Chemical Bank, working—literally—in the basement. It wasn’t long before he catapulted up the food chain and built a $13 billion private equity firm.

On the day I went to visit him in his office, he was his usual amused and amusing self, padding around the place in his socks (he said he’d just been to the dentist which, at least to him, explained why he was shoeless). In the hallway were the remnants of a buffet lunch, which made me feel as if I’d arrived at the party just a little too late. Glenn being in socks only added to that.

“We do this everyday for our associates,” Glenn said, pointing to the salmon swimming in cooling mango salsa juices.

“That’s a nice touch,” I replied, grabbing a plate of the leftovers and heading to the private dining room adjoining Glenn’s office.

For some reason, giving employees free food is an instant morale booster. Perhaps because the profit margin for a person is 100 percent. As in, this is free, so I have 100 percent gotten my value out of this product, whatever it may be. There’s a familiar saying in journalism that if you want reporters to show up at a press conference, just lay out free food and even better, some free alcohol.

Before long, Glenn and I began talking about his career and like many of the people in this book, he was absolutely confident in his belief on what makes a successful career.

“You can choose one of two career journeys. One resembles a canyon where you coast downhill in your early years and then spend your midlife, when tuition and mortgage payments come due, trudging out. The other is more like a mountain, which is a steep and arduous climb in your thirties and forties but which then frees you later in life to have time for family, philanthropy, and service.”

He then went on to tell me about his early years at Chemical Bank and how the traders on the floors above him snubbed their noses at the geeky analyst.

“I suppose I was a bit of a nerd, and as a result, I was relegated to the unglamorous credit department,” he said.

“So what did you do?” I asked.

“Though I learned an enormous amount . . . I couldn’t get promoted because I was in the back office. So I went instead to Harvard, did my JD and MBA . . . it strikes me as better for all involved to harness the talents of young people rather than restrain and discourage them.”

Many people would describe someone like Glenn as a Wall Street guy. But I see something else—I see an entrepreneur. Yes, he did eventually start his own business. But even before starting his firm, Silver Lake Partners, Glenn already thought of himself as his own entity. His own company of one. Others didn’t get the value of this company, but he did and he grew it to success.

This is something I found to be one of the biggest distinguishing factors between the leaders and the followers, the CEO and the rest of us. Most of the people who are successful are either entrepreneurs or have an entrepreneurial mindset, even if they worked at the same company for decades. There were exceptions to the rule, but not a lot. Being a “company of one” is not a selfish mindset, but rather a healthy one. People who have this mindset are optimists, they’re more productive, feel more confident because they know their own value and it can’t be taken away.

What exactly is this mindset? Quite literally at the basic level, being a company of one is striking out on your own. For example, company X doesn’t get who you really are, everybody around you has blinders on and you would do a much better job just building your own company than to stay at company X for another 5, 10, 15 years. In other words, you’re like Glenn. Or in another example, you’re bored with being a corporate lawyer and the midlife crisis hits, which means six months later, you’re baking cupcakes at your own shop and you’re 10 times happier than when you were pushing papers charging $500 an hour. That’s easily being the company of one.

But more often than not, the company-of-one mindset is about freeing yourself from the idea that your job is your career. Your job is your avenue to a career, so long as the job and the career match. Sadly, it often doesn’t. But people who have this mindset are easy to spot. They always have a few projects going on. This person may be a marketing executive by day, but at night she’s writing a book. Or he’s working at IBM, but in his spare time, loves producing how-to videos on YouTube. They’re creative people.

Jeff Hayzlett literally was a marketing executive by day. He was the chief marketing officer at Kodak when he decided to leave and pursue his own projects. When I told him about this company-of-one mindset, he immediately got it.

“Brand of one,” he said over lunch at the Manhattan eatery, Tao.

He said he had about 40-plus projects going on at the same time, including a gig at Bloomberg Television as a contributing editor. He’d been a judge on NBC’s Celebrity Apprentice. He consults and advises companies on marketing and public relations but his biggest business is himself.

“I make the most from the speaking,” he said.

When I ask him what his brand is, he says he’s unabashedly one of the best marketers out there and a cowboy to boot. He advised me social media was most important in developing your own brand. He grabbed his iPad and showed me all the tweets he’d scheduled later in the afternoon, tomorrow, next week, and even next year.

“Whatever you have, put it out there and let it echo,” he said. And as if to drive home the point, he tweeted out to me after our lunch. I barely had a chance to figure out how to make my way back to the office and he’d already tweeted a note saying thanks for the lunch for all the twittersphere to see.

Sam Zell, the self-made billionaire real estate investor, said his entrepreneurial zeal might have been because he was “born 90 days after my parents’ arrival in the United States [from Poland].”

“I had the opportunity to watch my parents, as immigrants, deal with significant changes and challenges,” Sam says, relaxing in his Manhattan apartment. “And as I watched that, and I think about it, among the things that have made my career so unique are those common denominators of change and challenge.

“The ultimate definition of an entrepreneur is someone who is always thinking he can do things a different, better way. If he walks down the street and sees a painter on a ladder, he thinks, ‘Gee, if he’d moved the ladder to the middle of the wall, then he could paint both sides without having to go up and down the ladder as many times,’” he said. “I can’t tell you why I think that way, but that’s literally the way I think all the time. It’s always been that way. I look at things and see them differently than other people do.

“In my career, I’ve been industry agnostic. There aren’t a lot of investors who have been in rail car leasing, container leasing, electrical distribution, waste energy, bicycles, natural gas, food additive manufacturing, logistics, and myriad other industries. I’m very much like a private equity guy is today except that I’ve always been a private equity guy—with my own private equity.”

Later, I thought about what Sam said. My parents did not come from Poland but from China. My father may have chosen a safe profession as a doctor but he pursued it with the same kind of risk that entrepreneurs do. My relatives all thought he was crazy to move to a country whose language he did not know, to try to practice medicine in a system that did not recognize his medical training, and to do all this with barely any savings to his name and three people—my mother, my sister, and myself—to support. At age 40, he arrived in the United States with $30 in his pocket, no job, and a fierce determination to make things work.

Martin Sorrell also waited until he was a 40 to start his own business. Martin is a punchy, outspoken advertising executive who founded WPP, one of the world’s largest advertising agencies, which earned him a knighthood in his native Britain. On his shield he has inscribed in Latin his motto: Celeritas et Perseverantia (Persistence and Speed).

“I probably could have [started my company] at thirty-five,” he tells me. “There are people who are good at running companies but not starting companies and I wanted to do both . . . I didn’t want to start a rinky-dink company. I only own two percent of the company or a little bit under two percent which, to me, is a lot of money, but to some others, they think that’s chicken poop. But rather than owning, say eighty percent of something smaller, I’m quite happy to have two percent of something that’s much, much bigger.”

When I looked up later the public information on WPP, I learned Martin is worth about $350 million just on his shares alone in the company he founded.

On the entrepreneurial mindset, Martin said: “Founders have different, I think, emotional connections to what they do. I mean, if you’re a hired hand or a turnaround expert, your loyalty and emotional commitment to the company that you’re running is different than if you started it . . . you just think differently. There was a famous football manager in the UK called Bill Shankly who was the manager of the Liverpool football club . . . this was when they were very successful. And he said, ‘Football is not a matter of life and death. It’s more important than that.’ So WPP is not a matter of life and death—it’s more important than that. So just like Berkshire Hathaway for Warren Buffett or JPMorgan for Jamie Dimon, it’s as much a part of them, you could argue, as their family. Their family probably comes first, but it’s as much a part of them as their family.”

When I looked up the quote later, the official line from Shankly went more like: “Some people believe football is a matter of life and death, I am very disappointed with that attitude. I can assure you it is much, much more important than that.”

“I wear this jersey and I bleed this blood,” Jamie Dimon told me a few months later at his headquarters in midtown Manhattan. “I feel responsible for our 250,000-plus employees. I wouldn’t leave here and do something else at another corporation . . . I’m very proud of our company and I want every employee to be proud of it.”

If there is a bank CEO who has his own brand of one, Jamie Dimon does. He was revered during the 2007-2008 financial crisis as the one leader who did not come under fire for bad management. While fellow CEOs were succumbing to their own bad decisions, Jamie looked like the smartest guy in the room. Time magazine named him to the world’s 100 most influential people list in 2008, 2009, and 2011. He was called CEO of the year by Institutional Investor, a finance-focused magazine, in 2011.

When I met him, he had just been through one of the toughest years of his career at JPMorgan. Regulators, the press, and critics were all hounding him over the so-called London Whale trading scandal where some bad trades at a London office cost the firm more than $6 billion. The event even has its own Wikipedia page. I could tell the situation really hit Jamie personally. He said he spent a weekend writing out his annual letter to shareholders to give his final thoughts on the scandal. He told me he wrote the letter by himself with no edits—it was a letter from him personally to everyone.

Even though he didn’t start JPMorgan—the bank says it was founded in 1799 as The Manhattan Company and at one point in its complicated history, it was called Chemical Bank (yes, the same Chemical Bank that did not promote Glenn Hutchins)—Jamie helped build the firm after its 2004 merger with Bank One, where he was chief executive. In other words, the JPMorgan of today is largely Jamie Dimon’s vision.

“I see our executives, they get in the elevators, I always say hi. I have administrative town halls, they all call me Jamie. They all know me. They’ll pat me on the back, ‘Hey you!’ The mailroom guys will say hi to me.

“There are some companies where executives have their own elevator. You cannot send that message to your people. I remember getting into an elevator once and the employees were talking about me. I said, ‘I’m back here!’ ”

“That really happened?” I asked.

“Yeah, they didn’t know I was in the back. I don’t know if what they were saying about me was good or bad. I just wanted to give them a heads up.”

The way Jamie talked about his company was with the same affection I heard from Martin and Sam, and would later hear from Warren Buffett. All had a solid foundation of who they were, their own companies and brands, and that translated into their companies. When you start something that is your own, when you control and own your own destiny, it’s not just life and death. It’s more important than that.

********

The fact is, most people would love to be like Sam—their own boss. According to an Edward Jones survey in 2012, 70 percent of workers liked the idea of being entrepreneurs at work. But only a puny 15 percent thought they had what it takes to be one. The biggest fear preventing people from pursuing their entrepreneurial dreams was the loss of their savings. The second biggest fear is essentially the same thing: a lack of support or safety net if they failed. None of this is surprising but then again, it’s not surprising that many people feel they’re stuck in a career rut.

Graham Weston is another billionaire entrepreneur (eventually in my world of business news, billionaires pop up like weeds) who recently co-authored a book called Unstoppables. The book is about creating more self-made business owners in the country and in the foreword, Graham recalls how he went back to his alma mater of Texas A&M University to give a talk.

“After offering a few remarks, I asked the students ‘How many of you would like to start your own businesses one day, or work for a young business?’ Practically every hand shot up,” Graham writes. “Then I asked ‘And how many of you will be doing that as soon as you graduate from A&M?’ There were a few chuckles around the room, and nearly all the hands came down. It seems there was a huge gap between the dream of entrepreneurship and the real-life plans most students had created.”

I have never owned or run my own business, but any profession, including journalism, can have entrepreneurial aspects to it. I create things and that means finding my own stories and creating my own show. I have always worked for myself even though I have never once worked on my own. In television news, it’s important to be part of a large network with the resources and the distribution to be seen by the widest possible audience. But even that may change as journalists begin to think more like entrepreneurs. And entrepreneurs like Reed Hastings of Netflix, Jeff Bezos of Amazon, and others begin to change the way television is delivered, period.

What’s the driving force behind entrepreneurial tendencies? Jay Samit, a serial entrepreneur who has created ooVoo, one of the fastest-growing apps rivaling Skype, joked: “Maybe because my mother never hugged me enough when I was a kid. I’m always seeking approval from others.” No surprise that I learned later Jay studied to be a journalist at UCLA.

Jay is a slim, boyish-looking guy in his fifties who shoots back and forth from New York to Los Angeles, where he not only runs his company but also teaches at the University of Southern California. Jay has both worked for himself and also rose up the senior ranks as a music executive at Universal, Sony, and EMI. He described back to me the company of one concept.

“What a person should do is realize that they have to be a brand of one. They’re going to have to reinvent themselves and their skill set nonstop. Think of a doctor that’s my age. That means they got out of medical school twenty-five years ago. The majority of drugs, treatments, machines—everything is completely different, right? There’s nothing that’s done the same as when they got out of school. So if a doctor didn’t keep on being a lifelong learner, they couldn’t be a doctor. Well, that’s the same for a cook, a graphic artist, and an advertising executive—name your field. Journalists that thought they would get a lifelong thing writing for a newspaper—they’re gone.”

“What’s your brand?” I ask.

“My brand is ‘you’ve got a problem and I can help solve it.’ No one ever hired me for my looks, right?” he said, chuckling.

Jay told me he has two rules for his managers to encourage entrepreneurial thinking.

“Every direct report that I’ve had for at least the past fifteen years I give the following two rules to, okay? You don’t work for me, I work for you. My job is to give you the resources that you need to do your job.”

“Do they believe you?” I ask.

“Sometimes yes and sometimes no. Rule number two makes it very clear. If you work for me for a year and you do not make a mistake, I will fire you.”

I look a little surprised. “And you’ve done that?”

“Oh yeah, I do. [Being] an entrepreneur is not for the faint of heart. The perfect kid that stayed up all through school and got the perfect grade and has the stomach in knots is not cut out for this. They can’t handle failing and the humiliation.”

I make a mental note to myself about how many nights I tossed and turned, worried about getting straight A’s on my report cards. I’m pretty sure if Jay and I had been classmates he would have been the bad ass in the back while I was the uptight, Little Miss Perfect A’s in the front.

Other managers may not go to such extremes as Jay, but you get the point.

As I mentioned, there’s usually two ways a person finally discovers their company of one. In the first, there is such a burning desire to do something, you can’t ignore it. You’re miserable until you satisfy this inner yearning. Jim Reynolds, the CEO of a boutique investment bank, told me that he was the best bond salesman in the Midwest for Merrill Lynch before he left it all to start his own firm. He was good at his job and making a lot of money. But instead of being happy about the future, it looked frightful.

“I really began to get a little bit afraid that I would sit there on the desk, stay on the bond desk, move up to head of fixed income, but still not accomplish the things I knew I was capable of,” he said. “I got really scared. I said, ‘Jim you could do so many more things, but you’re scared to leave here, but you should do those things, they’re inside of you.’ Eventually, the fear reversed itself—I developed a larger fear of staying there not realizing my potential than the fear I had of walking away from my career. Once that happened, I was off to the races.”

He left with half a million dollars from Merrill Lynch to start his own firm, which sounds like a lot of money except when you are trying to compete with companies that have billions of dollars and thousands of bankers. As luck would have it, an old friend of his from decades ago heard he wanted to start his own business. His friend was now the vice chairman of First Chicago Bank.