Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Nick Hern Books

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

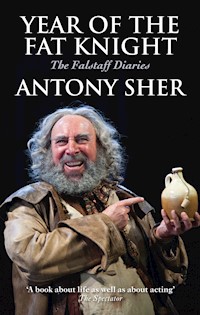

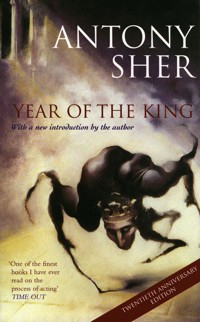

A classic of theatre writing, a unique insight into the creation of a landmark Shakespearian performance. Antony Sher's stunning performance for the Royal Shakespeare Company as Richard III on crutches – the so-called 'bottled spider' – won him both the Laurence Olivier and Evening Standard Awards for Best Actor. This book records – in the actor's own words and drawings – the making of this historic theatrical event. This edition of Year of the King is published on the twentieth anniversary of the RSC's 1984 production. It includes a new introduction in which Sher looks back at what has happened to him and to the world in the intervening years.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 426

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Antony Sher

YEAR OF THE KING

An Actor’s Diaryand Sketchbook

with an Introduction by the author

NICK HERN BOOKSLondon

www.nickhernbooks.co.uk

For my parents and Jim

Contents

Title Page

Introduction

April 2004

1 Barbican

August–December 1983

2 South Africa

December 1983

3 Acton Hilton, Canary Wharf and Grayshott Hall

January–April 1984

4 Stratford-upon-Avon

April–August 1984

About the Author

Copyright

Fool, of thyself speak well. Fool, do not flatter.

Richard III, v. iii

Introduction

Friday 9 April 2004

Last Saturday night saw the final performance of Othello at the RSC’s Swan Theatre in Stratford, prior to its Japanese tour and London run. To mark the occasion, my dresser Keith Lovell gave me a farewell gift: a small framed photograph. I stared at it in astonishment. It showed me twenty years earlier, backstage at the main house, in the middle of a performance of Richard III. It must’ve been taken just before or after the Coronation sequence which we invented for our production, since I am wearing the vast red silk robe with the special clasp that allowed us to reveal Richard’s naked deformed back during the annointing ritual. Mal Storry, who played Buckingham, is posing for the camera behind me, and to one side is my then dresser, the foul-mouthed, good-hearted Black Mac. Both Mal and Mac look rather deadpan, while I have a strange sideways smile on my face.

What strikes me first is not how young I look – though this is fairly alarming – but how relaxed. For the journey towards Richard III, told in the pages of this book, was a difficult one, full of anxiety, self-doubt and struggle. Back in 1984 it felt like my whole life depended on the attempt to conquer this one great role. Yet the photo shows someone just larking about in the wings. It looks like just another show, just another part.

And here I am now, in 2004, still working for the RSC – my love for the company undimmed – and indeed playing another of Shakespeare’s villains, Iago, a man so thoroughly disturbed and disturbing that he makes Richard III look like the good guy. So what’s changed? Everything. Twenty years might seem like a long time, but it doesn’t feel long enough for some of the differences between the world I was describing in Year of the King and the world now.

Most extraordinary is what’s happened to my birthplace, South Africa. At the time of writing the book, the system of apartheid seemed immovable, and its brutalities knew no bounds. And yet now, in this very month of this very year, South Africa is celebrating the tenth anniversary of its first democratic elections. Democratic elections? In South Africa? Ask the thirty-five-year-old in the photograph and he’d have told you it was impossible, at least not without the streets running with blood. Yet that didn’t happen either. Instead a miracle did. A miracle that began with one remarkable man walking out of prison to freedom.

On a personal front, much has happened too: as a gay man I’ve come out publicly (in this book I’m afraid I’m still very coy about my relationship with my then partner, Jim Hooper), and my father has died, my funny, difficult Dad, and I’ve been knighted, and I was in a clinic for cocaine dependency, and . . . well, if the reader is interested, they could look at Beside Myself, my autobiography. Year of the King was my first book, but I’ve since published seven more, as well as a stage play, I.D. Writing is now a serious rival to acting in my professional affections, and I’d be hard pressed to say which occupies the place of first love.

Re-reading Year of the King I was surprised by my obsession with Olivier’s Richard III. At the time I genuinely thought there was such a thing as a definitive performance of a Shakespeare role or play. Yet since playing the role myself, I’ve seen two other Richard IIIs that are certainly as good as anyone might hope for: Ian McKellen’s chillingly sour Blackshirt at the National, and Simon Russell Beale’s glorious poisoned toad at the RSC. I now believe that a significant part of Shakespeare’s genius, and one of the reasons why his work has lasted four hundred years, is that he constantly yields himself to re-interpretation. God knows what he himself would make of our endless and busy explorations of how to stage his plays. An all-female Shrew or an all-Yorkshire Antony and Cleopatra, a circus Dream, the roles of Henry V and Henry VI played by black actors, a Hamlet who vomits up his father’s Ghost, or indeed a Richard III on crutches . . . would he be dismayed by these portrayals? I hope not.

For me another big difference between 1984 and 2004, one which is vital to record here, lies in my approach to speaking Shakespeare’s language. There’s a very significant diary entry on page 228 of Year of the King, dated Sunday 10 June, the weekend before we opened the show: ‘Time to stop and think, which I don’t really want to do. Refuge in the Gielgud book, The Ages of Gielgud, only to come across John Mortimer’s lament on modern verse-speaking. I snap it shut as if killing a bug.’ The truth of the matter is that I was terrified of the verse, ashamed of my inexperience with it, and nursing a secret fear that I was trespassing anyway. Wasn’t classical theatre the territory of handsome, rich-voiced British giants like Gielgud and Olivier, and out of bounds for little Cape Town nebbishes like me?

I now feel bold enough to answer that question with a resounding no. Shakespeare belongs to us all.

Richard III was my first attempt at one of the great roles, and Iago is my latest. In between there’s been Macbeth, Leontes, Titus and Shylock, as well as several other classical parts, like the eponymous heroes of Tamburlaine the Great and The Malcontent, Caesar in The Roman Actor, Vindice in The Revenger’s Tragedy. In fact, I believe it’s the experience of playing Shakespeare’s contemporaries that has made the speaking of Shakespeare himself easier for me. The other writers don’t have Shakespeare’s gift with the verse – despite all their strengths they don’t have, let’s face it, his genius – and so they are much harder to speak. After you’ve battled with, say, the monotonous thump of Marlowe’s mighty lines or Tourneur’s awkward, twisting mouthfuls of words, you come back to Shakespeare with such relief, such joy. He’s done all the work for you. All you have to do is breathe it in and speak it out; just let it live in the air. This is, of course, easier said than done. But only by doing it, by practising the skills, will you eventually learn to master them. In the meantime the problem remains, and you can read about it in this book. I think it’s only right for me to confess here that the search for a spectacular physical shape for Richard was partly to compensate for my feeling of inadequacy with his language. You could say there was something symbolic about the eventual use of crutches.

These days I believe that performing Shakespeare begins and ends with the speaking of the verse, and no amount of physical bravura can make up for it. The brains of his great characters are more interesting than their bodies, and their brains are revealed in their manner of talking. Sometimes I sense there’s a public conception that all of his creations talk the same way, and that the Collected Works simply represent a great generalised wash of Shakespeare-speak. Far from it. Leontes’ neurotic, fractured utterances, Macbeth’s dangerously measured tone, Iago’s sick sex-fuelled images, and the sheer energy and wit of Richard’s speeches: these are all very different from one another. And it’s only by observing the individual ways these men express their thoughts that you can really get to their hearts.

My conversion to this new approach has been hugely helped by the most important change in my life between 1984 and 2004, and that is the relationship – seventeen-years-old next month – with my partner, the director Greg Doran. Just recently, Greg has been enjoying a terrific run of success with the RSC, conceiving and producing the Jacobethan Season (for which he won the 2003 Olivier Award for Outstanding Achievement), the double of The Taming of the Shrew and The Tamer Tamed, All’s Well with Judi Dench, and now Othello– and the press has repeatedly hailed him as one of the best Shakespeare directors in the country. Quite apart from all the other riches of our partnership, I feel I’ve been remarkably lucky to share my life with someone who knows and loves Shakespeare quite like he does, and who can communicate this passion with such vitality.

The Swan Theatre didn’t even exist in 1984 – it was still our rehearsal room then, the Conference Hall often mentioned in this book – but it is now the best auditorium I know, both as performer and audience member. It creates the illusion, essential for a good classical space, of functioning like a camera: switching from close-up to wide shot, from intimate to epic. It’s where I’ve done all my recent work with the RSC, and I always feel intense excitement when I arrive there to open a new show, and then intense sadness when it closes. So at last Saturday night’s performance of Othello I was already rather emotional when Keith suddenly presented me with the photograph of backstage life during Richard III.

Looking at it, I remembered that for all the struggle and doubt of the journey, and for all my inadequacy at verse-speaking, the role of the ‘bottled spider’ turned out so well for me that it’s been quite a hard act to follow. (Who was it that said, ‘Be careful of getting what you want’?) I also remembered that one of the other men with me in the photo, Black Mac, is no longer with us – he died in 2001 – and I miss him. As I hope this book reveals, he was a tremendous, larger-than-life character: originally from the North-East, working both as an army sergeant and a theatre dresser, rude, funny, kind, aggressive, full of contradictions, the sort of character Shakespeare would’ve loved. I like it when, in the diary entry dated 18 June, the day before our opening, Mac overhears me practising my speeches and says: ‘Clever, henny, clever, must be clever to remember that fokkin bollocks.’ But then later he confides in me: ‘The shows I’ve seen here, mate, the memories I’ve got, and I’ve viewed them from angles no other bugger has ever seen, no fokkin critic, not even the directors have seen them like I have, from my special places in the wings.’

So it is with Black Mac in mind – and other departed figures who haunt the pages of this book, like Dad, and indeed Olivier – that I now invite the reader to go on a twenty-year-old journey with me, in search of one of Shakespeare’s most dynamic and original creations, King Richard III.

Antony Sher, London

1. Barbican 1983

August 1983

Summer.

To be more precise, my thirty-fourth summer in all, my fifteenth in England away from my native South Africa, my eleventh as a professional actor, and my second as a member of the Royal Shakespeare Company.

These last two years have been eventful, a time of change. Last year, a successful season in Stratford playing the Fool in King Lear and the title role in the Bulgakov play Molière. Then, in November, an accident. In the middle of a performance as the Fool one of my Achilles tendons snapped and I suddenly found myself off work for a period that was to last six months.

Unexpectedly, this proved to be a happy time. Apart from anything else, the enforced rest was a chance at last to do all those paintings and sketches I’d long been planning. With my leg encased in plaster I’d sit for hours at my easel, just managing now and then to hobble a few steps back to get a better view. If anything, time passed too quickly. After years in a profession where you’re on public display, it was a relief to be a recluse for a change. My temporary disability made any journey from my home in Islington difficult and vaguely humiliating, so few were worth it. There was one exception.

The Remedial Dance Clinic in Harley Street is so-called because it serves as repair shop to most of the dance companies. Each day I would have to make my way there for long sessions of physiotherapy. This was a new experience for me. Strange, invisible currents of electricity, ultra-sound and deep-heat were passed into my leg and somehow started it working again. The process was slow. When the plaster first came off, the white shrunken leg revealed underneath was virtually useless. But gradually, stage by stage, my crutches could be exchanged for a walking-stick, then that was abandoned for boots with stacked heels, and eventually I was walking again in ordinary shoes. Now the process accelerated in the other direction. Running, then jumping, even trying a cautious cartwheel . . . preparing to go back into King Lear for the London run at the Barbican Theatre.

Another treatment of a very different sort, which I decided to try while I had the free time, was psychotherapy. Here the currents are stranger, but just as impressive. A man called Monty Berman has been listening patiently to the story of my life, yawning only occasionally. He makes comments like ‘Let’s validate that’, when I relate certain chapters, and ‘Bullshit!’ to others. I sit there, peering at him through my large, tinted specs, nodding in agreement, and then hurry away afterwards to check words like ‘validate’ in the dictionary.

So the Achilles incident has been a kind of turning point. Invisible mending from head to heel. Now I also pay regular visits to the City Gym, the Body Control Studio, and various swimming pools. I have developed, along with new muscles and energy, that brand of smug boastfulness on the subject of physical fitness: the kind that makes other people – and I remember this well from being on the other side – want to slap you around the mouth.

Going back into King Lear after six months away was like climbing on to the horse after it has thrown you. But its short London run is already over and I escaped uninjured. I have since opened in a new production of Tartuffe, playing the title role. This has been directed by Bill Alexander (as a companion piece to his production about its author, Molière) and has been a great hit with audiences, although less so, I believe, with the critics. My uncertainty stems from the fact that, along with a whole string of unwanted habits ditched since going to Monty, I have stopped reading reviews. I never thought I could do it, never thought I could live without them. But now, apart from the occasional twinge, I hardly miss them at all. Rather like giving up cigarettes, I suppose. Unfortunately, I still smoke quite heavily. Which is just as well, as I’m required to do so in the new David Edgar play, Maydays, which is about to go into rehearsal . . .

In the meantime, at the Barbican, Tartuffe and Molière continue in the repertoire.

JOE ALLEN’S Dining with a friend one evening, I notice Trevor Nunn [RSC Joint Artistic Director] at another table. He’s been on sabbatical ever since I joined the RSC last year, so I haven’t met him properly. Yet he is the RSC, so a social gesture might be required. Is it just a little nod? Or a little wave? Or a little of each with a mouthed, ‘Hi, Trev’? Or as much as popping over to his table and using the more formal, ‘Trevor, hello’? Luckily, his back is to me at the moment, so none of these decisions will have to be taken till my exit. For the moment I can concentrate on my Caesar Salad.

Hours later, my companion goes to the loo and almost instantly, as if by magic, Trevor Nunn is leaning forward on to my table.

‘Tony.’

‘Trevor!’

‘I did enjoy Tartuffe the other evening.’

‘Ah. Good. Thank you.’

‘I thought Bill Alexander got a perfect balance in the production between the domestic naturalism and the black farce.’

‘Yes, hasn’t he? It’s a –’

‘You really ought to play Richard the Third soon.’

‘Oh. Well. That would be nice.’

I look up at him hopefully. He smiles politely, a touch of enigma, and retreats, disappearing into the smoky, gossipy crowd . . .

Back at home, Jim [Jim Hooper, RSC actor] says, ‘Beware. It’s only Joe Allen’s chat.’ He’s quite right, of course, so I try not to think any further about it. Which is like trying not to breathe.

There was something unfinished in what he said. ‘You really ought to play Richard the Third soon –’ what might he have said next? ‘And I shall direct it’? Or, ‘– but not for us’? In the next few days these nine words, this innocent piece of Joe Allen’s chat is subjected to the closest possible scrutiny. It is viewed from every possible angle, upside down and inside out, thoroughly dissected, at last laid to rest, exhumed, another autopsy, finally mummified.

I try not to tell people about it, but it does have a peculiar life of its own, this ghost, and will keep slipping out.

I make the fatal mistake of mentioning it to Mum on one of my Sunday calls to South Africa. She instantly starts packing.

Another mistake is to mention it to Nigel Hawthorne (playing Orgon) at the next performance of Tartuffe. He twinkles. From then on the shows are accompanied by comments like, ‘Thought I noticed Tartuffe developing a slight limp this evening’, or, overhearing me complaining about putting on weight, he says, ‘Can’t you just edge it up for the hump?’

This successfully helps to shut me up, so apart from Mum’s weekly question, ‘And Richard the Third?’, as if we were about to open, there is no further mention made of it.

Time passes. Now it is winter.

Thursday 3 November

BARBICAN Paranoia is rampant these days, down in our warm and busy warren, miles below a chilly City of London. The end of the season, and for many their two-year cycle, is in sight. Rumours are rife about world tours of Cyrano and Much Ado, videos of Molière and Peer Gynt. Many are keen to return to Stratford where, rumour boasts, Adrian Noble will direct Ian McKellen as Coriolanus and either David Suchet or Alan Howard will be giving an Othello. But will people be asked back and, if they are, will good enough parts be on offer? It is widely believed that planning meetings are already in session in those distant offices above street level. As the directors pass among us for their lunches, suppers and teas, actors perform daredevil feats of balance in order to eavesdrop on conversations half a room away.

I am not above these feelings of unease myself. These years with the company have been the happiest of my career and I too don’t want them to end.

He says, ‘We really ought to have one of our meals soon.’

‘Absolutely. When?’

‘Well, I’m busy with Poppy technicals till the week after next. Has Bill spoken to you?’

‘No.’

‘Bill hasn’t spoken to you?’

‘No. What about?’

‘Oh, you know . . .’ He smiles. ‘Life and Art.’

‘Ah. No. Definitely not.’

‘We’ll let Bill speak to you first.’ He starts to go. Actors leaning towards us at forty-five degree angles quickly straighten, ear erections drooping. Terry turns back to me and smiles.

‘Oh, and don’t sign up for anything else next year. Yet.’

Friday 4 November

Bill Alexander rings. We arrange lunch for Monday.

MAYDAYS After the show, Otto Plaschkes comes round to my dressing-room. He’s a film producer, the latest in a long line to try to finance Snoo Wilson’s screenplay, Shadey. I was first approached about playing the eponymous hero (a gentle character who possesses paranormal powers and wants to change sex) over a year ago. I tell him I’m about to be talked to by the RSC, presumably about returning to Stratford. If he could be more definite about dates I could ask the RSC to work round them. He can’t, but it’s an encouraging meeting.

Sunday 6 November

Wake in the early hours. Meeting Bill tomorrow. It’s got to be Richard III. Got to be. Alan Howard’s was about three, four years ago, so it’s due again. And it’s the obvious one if they’re going to give me a Shakespeare biggy. Sudden flash of how to play the part – ideas are so clear in the middle of the night – Laughton in The Hunchback of Notre Dame. Very misshapen, clumsy but powerful, collapsed pudding features. Richard woos Lady Anne (his most unlikely conquest in the play; I’ve never seen it work) by being pathetic, vulnerable. She feels sorry for him, is convinced he couldn’t hurt a fly.

The Nilsen murder case – the Sunday papers are full of the trial of this timid little mass-murderer. The sick, black humour seems to have a flavour of Richard III: Nilsen running out of neckties as the strangulations increased; a head boiling on his stove while he walked his dog Bleep; his preference for Sainsbury’s air fresheners; his suggestion to the police that the flesh found in his drains was Kentucky Fried Chicken; even his remark that having corpses was better than going back to an empty house. The headlines squeal ‘Mad or Bad, Monster or Maniac, Sick or Evil?’

Spend hours sketching him, looking for some signs in that ordinary, ordinary face. The newspaper editors compensate for its ordinariness by choosing photos that are shot through police-van grills, or where the flashlights have flared on his spectacles to make him look other-worldly. But his ordinariness always seeps through. Isn’t it that which makes him really frightening?

I ask Jim whether he believes we all have a Nilsen within us. He says, ‘Well, certainly not you. You can’t boil an egg, never mind someone’s head.’

Monday 7 November

TRATTORIA AQUILINO Over lunch, Bill offers me Richard III. Although I’ve been expecting it, my heart misses a beat.

I don’t know whether Bill is any younger than the other directors, but he is somehow always regarded as such. After seven years with the company he is the only one titled Resident – rather than Associate – Director, his missing qualification being a Shakespeare production in the main auditorium at Stratford. In fact the only Shakespeares he’s ever done for the company were the Henry IV’s for the small-scale tour a couple of years ago. But after his successes this year with two classics (Volpone and Tartuffe) in The Other Place and The Pit this next step is inevitable.

We complement one another curiously, pulling in opposite directions – him towards the naturalistic, me towards the theatrical – and, I hope, stretching one another in the process. Almost the only thing we do have in common is a serious commitment to scruffiness. We both seem to find our days too short to waste time on shaving, brushing hair, or doing anything with clothes other than washing them and jumping into a familiar, unironed assortment hurriedly.

He is quite frank about next year’s Stratford season. They did try to get Howard and McKellen, but failed. So they have resolved instead to introduce a new, younger group of Shakespearian actors. Roger Rees has been mentioned as well as one or two others whom he won’t name yet.

I am flattered to be thought of in these terms, but am keen to know what else they have in mind for my season. Last year in Stratford convinced me it is no place to spend a whole year unless you’re constantly employed or a devoted ruralist.

He says Henry V is being considered and wonders aloud what I feel about playing him. He stresses that this is not part of the offer, hasn’t even been mooted at the directors’ meetings. I reply that it’s a part that would be challenging rather than wildly attractive. We also talk briefly about Othello (Iago, obviously), Troilus (he mentions Thersites but, as he’s deformed, that seems too close to Richard III; I steer towards Pandarus – does he have to be older?), As You Like It (Jaques? Yes please. Touchstone? No thanks), Merry Wives (Ford? Yes, absolutely).

We talk briefly about Richard. I feel he should be severely deformed, not just politely crippled as he’s often played. Bill says one should identify with him: a man looking in from the outside and thinking, ‘I’ll have some of that.’

I mention meeting Trevor in Joe Allen’s and how I’m worried by the immediate association of Tartuffe with Richard. He smiles. ‘I’m not asking you to play Richard like Tartuffe, or because of Tartuffe.’ But it’s a happy opportunity at last to discuss the inexplicable transformation that show made from the unhappiest rehearsal period (a major cast change, a mistaken lack of faith in the new translation, days of unremitting gloom) to this highly popular success we have on our hands. Have we just had a lucky escape? My own performance certainly feels like a survival kit rather than bricks and mortar. Bill feels that, although by accident rather than design, the mixture has turned out to be an exciting one – bourgeoisie invaded by gargoyle. I’m still not sure.

Coming to the end of the meal he asks, ‘So how would you like me to report back at the next directors’ meeting?’

‘Well, ideally I’d like to be in four shows, no less than three, the majority to be Main-House Shakespeares, let’s say two biggies and one supporting, and then perhaps one new play at The Other Place.’

‘And coffee to follow?’ the waitress is saying at the next table.

We leave the restaurant and Bill jumps into a passing taxi. We’ve only had one bottle of wine, but I’m left standing unsteadily on Islington Green, my head spinning. All I can think of is Michael Gambon telling me about driving up the MI to Stratford to do a show last year: ‘There’s all these cars gliding past, Tone. Men in shirtsleeves, jackets hanging neatly from those little hooks in the back, eyes glazed, commuting back and forth like zombies. And then this thought suddenly hits me, like for the first time, and I say to myself, “Michael, you’re driving up to Stratford-upon-Avon to play King-Fucking-Lear!”’

Tuesday 8 November

MONTY BERMAN SESSION He’s pleased by the Richard III news, but as soon as I mention I would find Henry V more difficult to play he pounces on this and won’t let go. By the end of the session I am totally convinced that unless I play that part my mental health will be in the gravest danger; then I remember and say, ‘But Monty, that’s not the one that’s been offered.’

Phone my agent, Sally Hope, who’s very laid back indeed about the news. I know she wants me to leave the RSC, feels I’ve been there long enough.

So I’m left to rejoice on my own. Buzzing around the house with the text, doing the speeches. This is almost the best time with any part, when it’s on offer but you haven’t said yes. You can have an unadulterated, indulgent wallow in it.

An image of massive shoulders like a bull or ape. The head literally trapped inside his deformity, peering out. Perhaps a whole false body could be built, not just the hump, to avoid having to contort myself and the strain or risk of injury that would entail.

Already dropped the Laughton image. Or maybe that’s how he starts – an unkempt mess. Then, after ‘a score or two of tailors / To study fashions to adorn my body’, his grossness is transformed into some very impressive image – in the same way Nazi uniforms were so flattering that all sorts of odd-looking men, the undersized, the obese and the club-footed, all looked sensational in them.

My copy of the play is rather irritating for a wallow like today’s. It’s full of scribblings and sketches. I’ve been in the play before, playing Buckingham to Jonathan Pryce’s brilliant Richard (a natural, born Richard) in Alan Dossor’s 1973 Liverpool Everyman production. Following hard on Brook’s Midsummer Night’s Dream, it was set in a circus lions’ cage, everyone was in track suits (different colours for the different factions) and had white faces. We all had to learn acrobatics, aiming for back-flips and eventually settling for forward-rolls. In retrospect the production was vintage Golden Age Everyman. Anarchy ruled. After Tyrrel reported the successful murder of the princes, Jonathan used to slip in a ‘Nice one, Tyrrel’ between some immortal couplet. In his tent at Bosworth he used to bring the house down by referring a line about ‘soldiers’ to the strips of toast on his breakfast tray. Hastings’ head was passed like a rugby ball, each of us screaming as it landed and passing it on. In the hands of brilliant, dangerous actors like Jonathan and Bernard Hill (who played a succession of murderers and mayors) the clowning was inspired, departing from the rehearsed scenes and taking cast and audience on a magical mystery tour which, more often than not, proved to be the highlight of that night’s show. I had no such courage and remember feeling woefully inadequate. I settled instead for a careful, detailed caricature – Buckingham as a smooth-talking, suave aristocrat with a copy of The Times, a monocle and solidly sleeked-back hair which I relied on for my biggest laugh: ‘My hair doth stand on end to hear her curses.’

Sunday 13 November

Dickie [Richard Wilson, actor and director] phones from Bangalore where he’s filming Passage to India. So at last I can shout it halfway across the world – ‘They’ve asked me to play Richard the Third!’

‘Good,’ comes the polite reply, brimming with sub-text. Of all my friends Dickie has been the least reticent in suggesting that my work has deteriorated with the RSC – particularly in Tartuffe– and the most genuinely concerned that it shouldn’t be allowed to continue.

Next, Mum phones from South Africa. But her response is muted as well. After all, she’s known since August.

Monday 14 November

MOLIERE An alternative future presents itself. In the audience tonight sit two film producers, one American, one British. They’re going to make a film about Albert Schweitzer and are looking for someone to play the part. Tonight’s performance was sold out, but I managed to have them squeezed in by selling part of my soul. Could this be my Gandhi? My Lawrence of Arabia? Sure it’ll be tough spending two years filming in the leper colonies of Central Africa, but then there are the premières, the Royal Command Performances, the Oscar ceremonies . . .

I hurry to the stage door afterwards, a hue of mascara and stage blood still glistening around my hopeful eyes. The American producer looks exactly like an American producer, rather like Orson Welles. He steps forward to greet me:

‘Bravura performance, Mr Shw . . . Sht . . .’

‘Sher.’

‘Yup. But let me give it to you straight. You are not our Schweitzer. The one thing that Schweitzer was, was tall!’

Tuesday 15 November

MONTY SESSION He sits looking at me, all folded round himself, long limbs so relaxed they seem to bend anywhere like elastic, a little cushion sometimes held within the spiral. A red sweater is sometimes draped round the shoulders. The face is long; it has great wisdom; the eyes are tired, doctor’s eyes – they’ve seen a lot of what there is to see. He works as a GP (at the age of sixty-one cycling daily from his Highgate home to the Lewisham practice), an acupuncturist and psychotherapist, is on the council of European Nuclear Disarmament, writes the occasional book, goes mountain climbing in the Himalayas in his spare time.

His phrases: ‘Let me posit . . .’, ‘Let me share with you . . .’; ‘I hear you’, to reassure; his favourite form of refutation – ‘Bullshit!’ His toughest rule: you are never allowed to answer, ‘I don’t know.’ And you don’t half make some progress when you can’t hide behind that one. At our first meeting back in March he said, ‘You’ll go through various attitudes towards me. You’ll mistrust me, then you’ll love me like a father, then I’ll be a guru, then you’ll hate me, and then with any luck you’ll see me as just another person.’ I don’t think I ever got past the guru stage.

And he’s South African. Or was. Originally from good Communist Jewish stock, he was imprisoned after Sharpeville for distributing leaflets (in prison he claims to have given a notable Lady Bracknell), exiled and can never return.

It is South Africa that we discuss today. Recently I’ve had this yearning to go back to visit and see my family. But this feeling is most uncharacteristic – I’ve been back only once in the fifteen years away; that was eight years ago. For so many years I was a closet South African. Having to say ‘I was born in South Africa’ stuck in my throat like a confession of guilt.

Monty is delighted. Thinks it is an excellent idea to go and have a grub round in my roots, rub that soil through my fingers; he sees it as an encouraging development in our work together.

I confess to him (so much of this is like Confession, I wonder if there’s less call for therapy in Catholic circles) that another reason in the past for not returning is that I wanted to wait until I could step off the plane to the crackle of exploding flashbulbs. This seems silly now. He says it is a common syndrome – people who’ve left home to make good elsewhere want to return as heroes.

‘Anyway,’ he says, ‘maybe there will be photographers at the airport.’

‘There won’t. I’m not famous.’

‘You’re well known.’

‘There won’t be photographers, Monty.’

‘So, all right, maybe one photographer.’

I leave the session very uplifted, very excited. Going home.

Wednesday 16 November

Today is a special day. The first anniversary of my accident in Stratford . . .

Halfway through the evening performance of King Lear. We’d done the first storm scene. I was alone on stage, coming to the end of the Fool’s soliloquy. Goosestepped to the front of the stage, ‘FOR – I – LIVE – BEFORE – HIS – TIME’, aware that I was slamming my feet down harder than usual . . . swung into the little dance – BANG! My first thought as I fell was, ‘Fucking floorboards!’ I looked round. No hole in the stage. No floorboard sticking up. Then what had hit the back of my leg? What had made that noise? A bullet? Dazed, I looked towards the audience for the assassin or some explanation. Realised I was sitting on the floor, had missed several cues, the music was unwinding round me, I tried to rise, fell again. Hopped off stage and fell. Lear, Kent and Fool have to go back on almost immediately. To Gambon (King Lear): ‘Mike, I can’t walk!’ He, thinking this was part of our patter, said, ‘Well then you’d better crawl, hadn’t you? Stupid red-nosed tit.’ Cue light. They ran on. I crawled after. The audience probably thought it was intentional – Lear, Kent, Poor Tom running round the heath, the Fool flagging, crawling behind . . .

End of that scene. Crawled into the wings. A crowd of stage-managers had gathered. ‘Tony, what’s the matter?’ ‘Don’t know, can’t stand up.’ ‘Are you in pain?’ ‘Don’t know, don’t know what’s going on.’ The next entrance was from under the stage, down several flights of stairs. Mal Storry (Kent) picked me up in his arms and carried me like a child . . .

For the Fool’s death I had to step into a dustbin. Impossible to do without transferring the full weight from one leg to the other. This was the worst moment. For weeks afterwards this was the moment that I couldn’t think about without going cold, the moment of stepping on to this soft dead leg, the nauseating pain as it took the full body weight . . .

Interval at last. Carried into the wings. A St John Ambulance man from front-of-house said, ‘Might be the Achilles tendon.’ Ian Talbot, my understudy, was staring down at me white-faced . . .

Carried up to the dressing-room on a chair. The St John Ambulance man and Steve Dobin, the stage-manager, puffing and struggling like Laurel and Hardy getting that piano up those stairs . . .

Sat in my dressing-room with a crowd of actors at the doorway peering in, Sara Kestleman saying, ‘I think it might be the Achilles tendon, my darling, it happened to me at the National.’ Left alone to change. Took off the red nose, saw myself in the mirror – my face a Francis Bacon smear of sweat and clown colours . . .

Pete Postlethwaite [RSC actor] drove me to the hospital. At first we couldn’t find it, then when we did, couldn’t find Casualty. The little country hospital looked closed for the night. At last, a weary nurse on duty. She said no one could see me till lunchtime the following day, gave me a bandage, painkillers, two mogodons and an unofficial diagnosis: ‘Achilles tendon, I would have said.’

‘The tendon has ruptured completely,’ said the surgeon who operated a week later, ‘up the back of your leg like a venetian blind.’

A mysterious accident that befalls sportsmen in top condition, little old ladies stepping off the curb, and a surprising number of actors: Judi Dench, Tim West, Nick Grace, Brian Cox, Paul Hertzberg, Sara Kestleman and I, all part of the Achilles mythology.

Friday 18 November

An unsettling dream during the night: The first read-through of Richard III on the balcony of a Tuscan villa overlooking a town square. Roger Rees playing Clarence. The moment comes to start. Everyone looks towards me. I know the play begins ‘Now is the winter . . .’, but cannot say it. Everyone waits, staring. A crowd starts to gather in the square below. Someone says, ‘Oh don’t mind them, they’re the same old assassins that gather every time a Pope is elected.’

Unable to get back to sleep, I find my copy of the play and have a proper look at the speech.

‘Now is the winter . . .’

God. It seems terribly unfair of Shakespeare to begin his play with such a famous speech. You don’t like to put your mouth to it, so many other mouths have been there. Or to be more honest, one particularly distinctive mouth. His poised, staccato delivery is imprinted on those words like teeth marks.

I sit in shock, in the middle of the night, staring at the text.

‘Now is the winter . . .’

God. It’s as hard as saying ‘I love you’, as if you had just coined the phrase for the first time.

Has Olivier done the part definitively? Surely not. Surely the greatness of the play is lessened if such a feat is possible? Surely contemporaries thought the same about Irving, Kean, even Burbage? The trouble is, Olivier put it on film.

To cheer myself up on the subject, I dig out my 1980 diary to read this entry: 28 January. The Roundhouse. With Dickie and the actor Philip Joseph to see the Rustavelli Richard III. A stunning production by this Russian company. Ramaz Chkhivadze plays Richard like a species of giant poisonous toad. And he touches people as if removing handfuls of flesh. I will never forget the moment of Accession. As the crown landed on his head it seemed to squash the face beneath it like in an animated cartoon. You knew it was going to be downhill for Richard from then on. Dickie thought it was a definitive production, but I’m not so sure. How can we know when so much of the experience was slightly dream-like, that is, in a foreign language? But Dickie was undeterred.

‘It makes me very envious,’ he said. ‘Mind you, they do have two years to rehearse.’

‘Yes,’ said Philip Joseph, ‘but think of the two-month Technical.’

Saturday 19 November

This letter has been pinned up on the Green Room notice board, concerning the moment in Tartuffe when I pull down my tights to commence the assault on Elmire, and my bum is exposed; it’s from a College of Higher Education:

‘Dear Sirs,

I attended a performance of Tartuffe with my Sixth Form pupils last night and we were all rather offended by the totally unwarranted nudity in Act IV. We have tickets for Cyrano de Bergerac on 2 December and I would therefore be grateful if you could let us know if there is any nudity in that, and if so, how much?’

They’re lucky it wasn’t more than just my bum: the rest is contained in a posing-pouch hidden under the smock, following a conversation in rehearsals that went, ‘Bums are funny, breasts funny-ish, but pubes, penises, testicles and vaginas are definitely not funny at all.’

Some thoughts on Richard III.

In several copies I’ve looked at it’s called The Tragedy of King Richard the Third. Yet a tradition has evolved of playing it as black comedy. I’ve never seen anyone play Richard’s pain, his anger, his bitterness, all of which is abundant in the text.

Literature and drama are full of angelic cripples, deformed but kindly and lovable: Quasimodo, Smike, the Elephant Man, Claudius in I, Claudius. It seems to me that Richard’s personality has been deeply and dangerously affected by his deformity, and that one has to show this connection.

But the problem in playing him extremely deformed is to devise a position that would be 100 per cent safe to sustain over three hours, and for a run that could last for two years. Play him on crutches perhaps? They would take a lot of the strain off the danger areas: lower back, pelvis and legs. And my arms are quite strong after months at the gym. Also I was on crutches for months after the operation so they have a personal association for me of being disabled. They could be permanently part of Richard, tied to his arms. The line, ‘Behold mine arm is like a blasted sapling wither’d up’, could refer to one of them literally.

The crutches idea is attractive, too attractive at this early stage. Must keep an open mind on the subject.

Worrying silence from Bill. It’s about two weeks since we met. I ring him. He sounds evasive. I sense that something’s wrong. He says that Richard III is still the only offer. Roger Rees has been talked to about a Hamlet and Ken Branagh about a possible Troilus.

But good news about the videos. Both Molière and Tartuffe are to be done. Bill will direct them himself with the aid of a technical director.

Monday 21 November

A DAY AT THE BARBICAN Walking through the foyers first thing in the morning, it’s like some futuristic city mysteriously depopulated. A pair of automatic doors have quietly gone mad during the night and can’t stop opening and closing.

At the top of the main staircase there is a plaque unveiled by the Queen at the Gala Opening on 3 March 1982. I was present and had an encounter which now seems to have a curious significance.

I was leading a little group to this staircase for the arrival of the Queen. Apart from Jim, the group consisted of RSC stalwarts Adrian Noble and Joyce Nettles. They knew the building much better than I did, as I hadn’t even joined the company, so why I should have been leading is something of a mystery. At the time I put it down to drunkenness – champagne had been flowing freely – but now I suspect it was more to do with A Greater Scheme Of Things. Anyway, leading I was. The Royal arrival was imminent. DJs and evening gowns shimmered and rustled; the lights tickled over jewellery and hair lacquer; the smell of exclusive scents, the sounds of sophisticated gossip and discreet champagne burps.

I turned back to beckon my flagging group and almost immediately crashed into someone heading in the other direction. I say crashed, but it was as soft and cushioned as befits a collision with Destiny. The recipient of my careless shoulder was an old man with a white beard and rimless spectacles. The face was vaguely familiar, the voice even more so.

‘Are you trying to kill me?’ he asked with the gentle humour of someone who has looked Death properly in the eye.

‘No,’ I replied with certainty. And then as an afterthought, ‘Sorry.’

And that’s all there was to it. That’s all that was said. It was puzzling that a little circle had cleared around us, me and Father Time, but not unduly worrying. He smiled and passed on. I joined my group who now stared at me with an assortment of strange expressions, as if they had witnessed some miracle. I smiled, nonplussed, a little drunk, and made to lead on.

‘Do you know who that was?’ demanded Jim.

The urgency of his voice caused me to swing round and stare after the retreating figure. Suddenly I recognised him, or rather recognised his wife – she was holding his arm now and steering him, to avoid further collisions with drunken actors in hired DJs – Joan Plowright.

The Queen arrived, but my encounter had so stunned me that I was pointing in the wrong direction, expecting her to come down the stairs instead of up them, and missed seeing her altogether.

It didn’t matter, for I had just brushed shoulders with Richard III.

This morning, almost two years later, a cleaner is hard at work, polishing the plaque. I arrive at the stage door. This is run like the reception desk of a modern hotel. Usually there are a few people standing around clutching briefcases (journalists, members of the government doing financial surveys) and a queue of members of the public who think they’re at the box-office.

I will be greeted either by Irish Shamus, large and friendly, ‘Hillo Towni,’ or by Cockney Ron with tomahawk head, ‘Aw’ri’ Toan?’

Into the corridors where Radio 3 is piped during the day: it gets everywhere. The uninitiated may be alarmed, going into a loo to find the 1812 playing. They pee, glancing nervously over their shoulders as canons explode in the cubicles behind them. On Saturdays Critics Forum might be on and if you’ve just opened in something, you might be under discussion. You hurry along the corridors then, hands clasped over ears, in an Orwellian nightmare, as disembodied voices tell you what they think of you, and it’s being broadcast all round the building!

In the evening the show is relayed, Main House or Pit depending on which corridor you’re in. It can change from The Tempest to Molière, Cyrano to Tartuffe, with the slapping of a swing door.

Today it is Maydays, so I move into the Number One dressing-room. This involves carrying my large cardboard box (containing shampoos, deodorants, aftershaves, vitamins, glucose, Rennies, Kaolin & Morphine, dressing gown, towel and little cushion for the quick zizz) from the communal Pit dressing-rooms down several floors to the individual Main House dressing-rooms on street level.

The Number One dressing-room (its number is actually Fifty-One, but that doesn’t have the same ring to it) looks rather like something out of a motorway motel. Characterless functionalism. Its main feature is a pay phone fixed on to the wall in a plastic module of almost alarming yellow. Otherwise there’s a sofa, three chairs, work-surface, wash-basin and a window. Through this you can watch legs and wheels going down the ramp to the car-parks. You cannot see the sky, but by twisting down and sideways you can just see a reflection of the sky in the glass building opposite. This is not to be sneezed at when you’re underground for most of the day.

Despite all, I love it, the much maligned Barbican. In a hundred years they will look on it with such affection. ‘Why can’t they build theatres like the Barbican nowadays?’ they will sigh.

Tuesday 22 November

MAYDAYS Neil Kinnock in the audience. The play was very moving as a result, like when George Harrison came to John, Paul, George, Ringo and Bert (in which I played Ringo). This fiction you’re playing is someone else’s reality, you hear the lines through their ears, as if for the first time, and they suddenly come out quite fresh. I didn’t want my character to defect to the Right tonight.

Afterwards I’m summoned to meet Kinnock. The corridor is full of men – Secret Service? Surely not. He is small, has instant charisma, and is very cheerful; in fact he positively glows with enthusiasm; the light he gives off is orangey, from his hair, freckles and gums. His wife tells us how she couldn’t get twelve decent seats for the performance. ‘They probably thought,’ she says in a Welsh accent even stronger than his, ‘that I was someone from the sticks bringing in a little charabanc for a night on the town.’ So they all sat right at the back. It seems they go to the theatre a lot – they recognise Stephanie Fayerman from a feminist fringe show.

Ron [Ron Daniels, RSC director] asks him whether he’s enjoying his new role as leader of the Labour Party. ‘Enjoying it!’ he laughs, an orange firecracker going off, ‘Enjoying it! Enjoyment doesn’t come into it. Enjoyment is for afterwards, when it’s all over and you can discuss your memoirs on television.’

When they’ve gone, Ali [Alison Steadman], Shrap [John Shrapnel] and a friend of his have a drink in my dressing-room. We’re all very star-struck, like schoolgirls at the stage door.

‘Wasn’t he nice!’

‘And so ordinary and easy to talk to.’

‘And so little.’

‘Seems much bigger on the telly.’

Discussion about power. Shrap’s friend says that you can’t want to lead any party without desiring power, which actually makes you unsuitable for the job. Like actors, politicians must have a basic flaw in their personality, or at least a peculiarity, that makes them want to do the job in the first place.

Richard III?

Wednesday 23 November

Molière has always been a strangely jinxed play. Right from the original 1935 Moscow production when, in order to get it on, Bulgakov had to do battle with everyone from Stanislavsky to Stalin. Last year it finally got its British première, ran about three months, and then my accident occurred, threatening to take it out of the repertoire – there are no understudies at The Other Place. Pete Postlethwaite volunteered to take over and was rehearsed into it. On the Saturday before he was due to open he hit black ice driving out of Stratford after a show and found himself upside down in a field, the car a write-off and his back injured. The show came out of the repertoire for the rest of that season. Sadly, in the following months Derek Godfrey, who had been playing Louis XIV, has died. And now David Troughton has to have a knee operation and will be out for six weeks. We’re rehearsing John Bowe into the part he plays, Bouton.

KING’S HEAD PUB, BARBICAN With Bill after rehearsals. Still no news. I’ve made a private resolution not to discuss any Richard III ideas. I must play down my enthusiasm for the part, even with Bill, if I am to get a full season out of them. As casting now gets under way they will have so many people to keep happy that I will quickly be put to one side as soon as they think they’ve got me. This resolution lasts as long as the first round of drinks. Then we both gleefully plunge into the subject uppermost in both our minds.