Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Quintessence Publishing Co, Inc

- Kategorie: Fachliteratur

- Sprache: Englisch

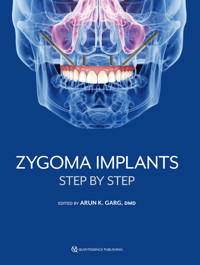

With success rates ranging from 95% to over 98%, zygoma implants are the standard of care in the treatment of patients with severe maxillary bone atrophy who cannot be rehabilitated with surgical bone augmentation and/or the placement of conventional or tilted implants. Because patients who qualify as candidates for zygoma implant therapy usually get only one chance to regain their masticatory function, the stakes for this treatment are very high, and that is why Dr Arun K. Garg undertook this project. Written by distinguished authors with decades of clinical knowledge, the book equips the experienced implant surgeon with comprehensive knowledge of every facet of the surgical and prosthetic treatment protocols for zygoma implant therapy, from patient evaluation and selection to step-by-step procedures and the management of complications, building the reader's knowledge from start to finish. Learn the ins and outs of zygoma implant therapy so you too can deliver this life-changing therapy to your patients.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 370

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

ZYGOMA IMPLANTS

STEP BY STEP

One book, one tree: In support of reforestation worldwide and to address the climate crisis, for every book sold Quintessence Publishing will plant a tree (https://onetreeplanted.org/).

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Garg, Arun K., 1960- author.

Title: Zygoma implants : step by step / Arun K. Garg.

Description: Batavia, IL : Quintessence Publishing Co, Inc, [2023] | Includes bibliographical references and index. | Summary: "Provides the rationale for using zygoma implants in cases of severe maxillary atrophy or trauma and details the supporting evidence for their use, their indications in clinical practice, and the many techniques and combination approaches available to clinicians"-- Provided by publisher.

Identifiers: LCCN 2022044704 | ISBN 9781647241575 (hardcover)

Subjects: MESH: Dental Implants | Zygoma--surgery

Classification: LCC RK667.I45 | NLM WU 640 | DDC 617.6/93--dc23/eng/20221209

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2022044704

A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN: 978-1-64724-157-5

© 2023 Quintessence Publishing Co, Inc

Quintessence Publishing Co, Inc

411 N Raddant Rd

Batavia, IL 60510

www.quintpub.com

5 4 3 2 1

All rights reserved. This book or any part thereof may not be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, or otherwise, without prior written permission of the publisher.

Editor: Leah Huffman

Design: Sue Zubek

Production: Sue Robinson

Contents

Preface

Contributors

1 Zygoma Implants: Rationale, Indications, and Overview

Arun K. Garg ǀ Angelo Cardarelli

2 The ZAGA Concept: A Multifaceted Approach to Zygoma Implant Rehabilitation

Carlos Aparicio

3 Anatomy and Pathophysiology of Maxillary Bone Atrophy

Guillermo E. Chacon

4 Zygoma Implants: Step-by-Step Surgical Protocol

Komal Majumdar

5 Oral Rehabilitation with Pterygoid Implants

Henri Diederich ǀ J. O. Agbaje

6 Two Zygoma Implants in Combination with Conventional or Tilted Implants

Arun K. Garg ǀ Renato Rossi, Jr ǀ Jack T. Krauser

7 Quadruple Zygoma Implants

Vishtasb Broumand

8 Multiple Zygoma Implants

Cesar A. Guerrero ǀ Marianela Gonzalez Carranza ǀ Adriana Sabogal

9 Zygoma Minimally Invasive Technique with Piezoelectric Instrumentation

Andrea Tedesco

10 Step-by-Step Prosthetic Protocol for Zygoma Implants

Komal Majumdar

11 Prosthetic Restoration of Zygoma Implants

Maria Del Pilar Rios ǀ Jack T. Krauser ǀ Thomas Balshi

12 Zygoma Implants in the Patient with Cancer or Maxillofacial Trauma

Renato Rossi, Jr ǀ Arun K. Garg ǀ Alfred Seban

Index

Preface

Over two decades have passed since P-I Brånemark published the first study demonstrating the efficacy of using extramaxillary implants to support a prosthesis in patients with an extremely atrophic maxilla. In the intervening period, numerous additional studies have confirmed the long-term stability and predictability of zygoma implants, with reported survival rates ranging from 95% to more that 98% over 3 to 12 years of follow-up. Today, zygoma implants are the standard of care in the treatment of patients with severe maxillary bone atrophy who cannot be rehabilitated with surgical bone augmentation and/or the placement of conventional or tilted implants.

This book is designed for experienced implant surgeons who wish to acquire both a broad understanding of the various surgical and prosthetic protocols being practiced around the world today as well as the knowledge to perform these procedures in step-by-step fashion in their own practices. Unlike many edited volumes, the chapters in this book are not a random collection of articles mashed together but a carefully selected and organized series of chapters that build the reader’s knowledge from start to finish.

The distinguished contributors were selected based on their decades of actual clinical knowledge and experience with zygoma implants and exceptional clinical skill. Each has contributed extensively to the rapid progress that has been achieved over the past two decades in our ability to restore function and esthetics in a long-neglected patient population. Additionally, because these authors come from many different parts of the world, this book represents the most innovative and advanced knowledge and techniques available anywhere on this topic.

Patients who qualify as candidates for zygoma implant therapy usually get only one chance to regain their masticatory function, so the stakes for this treatment are very high. For that reason, extra care has been taken to equip the reader with comprehensive knowledge of every facet of the surgical and prosthetic treatment protocols, ranging from patient evaluation and selection to step-by-step procedures and the management of complications. To help guide and enhance the reader’s comprehension, ample professional drawings and case illustrations have been beautifully reproduced for maximum educational benefit by Quintessence Publishing, the world’s preeminent publisher of professional dental literature.

Contributors

J. O. Agbaje, bds,dmd,mmi,phd

Postdoctoral Fellow

Katholieke Universiteit Leuven

Leuven, Belgium

Carlos Aparicio, md,dds,msc,dlt,phd

Founder and President of ZAGA Centers

Barcelona, Spain

Thomas Balshi, dds,phd

Retired from Private Practice in Prosthodontics

Fort Washington, Pennsylvania

Vishtasb Broumand, dmd,md

Private Practice in Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

Phoenix, Arizona

Adjunct Clinical Assistant Professor

Banner MD Anderson Cancer Center

Mesa, Arizona

Angelo Cardarelli, dds

Adjunct Professor of Oral Surgery

Vita Salute San Raffaele University

Private Practice

Milan, Italy

Guillermo E. Chacon, dds

Private Practice in Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

Puyallup, Washington

Henri Diederich, dds

Private Practice

Luxembourg City, Luxembourg

Arun K. Garg, dmd

Professor of Surgery

Division of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

Department of Surgery

University of Miami School of Medicine

Miami, Florida

Marianela Gonzalez Carranza, dds,ms,md

Clinical Associate Professor

Director of Undergraduate Oral Surgery Training

Texas A&M University College of Dentistry

Dallas, Texas

Cesar A. Guerrero, dds

Private Practice in Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

Houston, Texas

Jack T. Krauser, dmd

Private Practice in Periodontics

North Palm Beach, Florida

Komal Majumdar, dds

Private Practice

Navi Mumbai, India

Maria Del Pilar Rios, dds,phd

Associate Professor of Prosthodontics

Santa Maria University

Private Practice

Caracas, Venezuela

Renato Rossi, Jr, dmd,msc,phd

Director

Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery Residency Program

University of São Caetano do Sul

Private Practice in Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

São Paulo, Brazil

Adriana Sabogal, dds

Private Practice

Cali, Colombia

Alfred Seban, dds,phd

Head of Department of Oral Surgery

Paris Diderot University

Paris, France

Andrea Tedesco, dds

Research Fellow, Oral Surgery Unit

S. Chiara Hospital, University of Pisa

Pisa, Italy

Private Practice

Florence, Italy

Chapter 1

Zygoma Implants: Rationale, Indications, and Overview

Arun K. Garg

Angelo Cardarelli

Zygoma implants are often the anchoring mechanism selected by the interdisciplinary surgical/restorative team in the prosthetic reconstruction of the extremely atrophic maxilla, whether the maxillary defect is congenital in origin (eg, cleft lip and palate) or acquired via injury or following tumor resection in cancer treatment. In the surgical/restorative team, the surgical associates are guided by the restorative dentist’s decisions regarding type and placement of provisional and final prostheses. Both zygoma implants and traditional or tilted implants are often chosen to provide optimal prosthesis support and distribution of occlusal forces.

The literature confirms the safety, predictability, and cost-efficiency of zygoma implant procedures.1–9 When the maxillary bone cannot sufficiently anchor a prosthesis to restore the region’s function and esthetics via traditional implant placement, zygoma implants can often be a good solution. In these cases, zygoma implants not only reduce the overall treatment time because fewer implants are placed, but they also restore function immediately without the need for bone grafting, thereby avoiding the added morbidity of extra procedures. However, the patient will be subject to a more complex procedure, including sedation (general or deep) and more complicated and potentially problematic treatment conditions if the implants fail. Therefore, patient selection is crucial for zygoma implants. The scientific basis for zygoma implants stems from the anatomy of the zygomatic bone itself along with the surrounding cranial structures. These two factors must be considered to determine which patients are most suitable for the procedure as well as to develop appropriate perioperative treatment plans.

Rationale for Zygoma Implants

Insufficient maxillary bone often precludes the use of conventional or tilted implants to support prostheses aimed at restoring function and esthetics in the maxilla. Zygoma implants offer a solution to this problem, but the tradeoff is a more complicated procedure with more risks for the patient down the line. The anatomy of the zygoma and the specifications of the implants designed to exploit that anatomy provide clinicians with concrete evidence to support zygoma implant procedures.

Zygoma anatomy

The anteroposterior length of the zygomatic bone averages 14 to 25.5 mm and ranges in thickness from 7.5 to 9.5 mm. Upon placement of a zygoma implant, slightly more than one-third of the implant (14–16.5 mm) comes into direct contact with the zygoma’s solid, sturdy outer cortex, where the implant obtains primary stability10–14 (Fig 1-1).

FIG 1-1 The apical portion of the zygoma implant is osseointegrated into the zygomatic bone. The coronal portion of the implant can be osseointegrated into the alveolar crest, although on occasion it simply rests on the crest and is not osseointegrated into it. The body of the zygoma implant may be through the maxillary sinus, adjacent to the maxillary sinus by elevating the sinus membrane prior to implant placement, or outside of the bony housing of the maxillary sinus.

To ensure a palatal emergence profile of the zygoma implant, the original procedure called for implant placement within the sinus.15,16 The clear advantage to palatal emergence is that as the maxilla resorbs, the basal bone remaining in the maxilla will orient posteriorly to the alveoli while the zygomatic bone position remains constant. However, this emergence profile requires increased buccal cantilevers because of the relative bulkiness of the prosthesis required for such a platform.

Zygoma implant specifications

Zygoma implants sold in the United States generally are available in lengths ranging from 30 to 52 mm. Because clinicians must have some leeway in determining the proper path for drilling into the zygomatic bone, the implant emergence point in the palate may have to be widened. Therefore, zygoma implants are tapered in diameter, from 5 mm at the coronal end (about one-third the length of the implant) to 4 mm in diameter for the remaining apical end of the implant (Fig 1-2). The coronal portion usually has a 45-degree platform for connection to the prosthesis.12,17–19

FIG 1-2(a) Zygoma implants come in a variety of designs. The apical portion is always intended to osseointegrate within the zygomatic bone. (b) Zygoma implants are commercially available in a variety of lengths to accommodate differences in distance between the zygomatic bone and residual alveolar crest in each patient.

Patient Selection for Zygoma Implants

Patient selection for zygoma implants depends on patient expectations, maxillary bone indications regarding implant suitability, and a number of medical and dental contraindications that direct nontreatment or alternative treatment.17,20–22

Indications

Designed by Per-Ingvar Brånemark and ranging in length from 30 to 62 mm or slightly longer, zygoma implants anchor in the zygoma when there is insufficient or no available anchorage in the alveolar bone of the maxilla to support a full-arch prosthesis. Zygoma implants can be used alone or in conjunction with conventional implants. Often when the posterior maxilla suffers from near complete atrophy, there is still enough bone in the anterior maxilla to anchor traditional or tilted implants to assist in the positioning and support of a prosthesis secured primarily by zygoma implants4,7,23–26 (Fig 1-3). When the anterior maxilla is too resorbed due to defects7 (cleft lip or palate, tumor resection, or unsuccessful implant/bone restorations), zygoma implants are used alone to support and retain the prosthesis.1–3,5,6,27–31

FIG 1-3 Radiographic view of zygoma implants, pterygoid implants, and conventional or tilted implants in the maxilla.

Contraindications

As a major dental procedure, zygoma implants are contraindicated for many patients, including medically compromised patients with systemic conditions such as diabetes mellitus, patients suffering from acute sinusitis, and patients whose maxillary alveolar bone can support traditional implants. Depending on the severity of conditions, damage to the masticatory muscles (trismus) may also be a contraindication for zygoma implants, as may radiation treatments affecting bone quality in the head and neck regions.32,33

Perioperative Overview for Zygoma Implants

The original surgical procedure for zygoma implants has evolved over the years to accommodate the diverse restorative circumstances associated with individual patients and to prevent surgical and postoperative complications.

Original (intrasinus) surgical procedure

The clinician chooses general anesthesia or intravenous deep sedation for the procedure. For hemorrhage control and nerve blocks (superior alveolar, infraorbital, and greater palatine), local anesthesia is administered intraorally (the maxillary vestibule and the posterior hard palate). When deep sedation is used, the zygoma prominence is also treated with extraoral anesthesia/infiltration.12,18,34

When preparing the osteotomy and placing implants, clinicians generally use a contra-angle handpiece if the patient’s mouth opening is restricted. The keratinized gingiva is bisected between the tuberosities via a crestal incision. The clinician then makes vertical incisions posteriorly along the maxillary buttress and anteriorly within the midline region. An elevated mucoperiosteal flap reveals the alveolar crest, lateral maxilla and antral wall, infraorbital nerve, zygomaticomaxillary complex, and the lateral surface of the zygomatic bone cranially, to the area between the lateral/medial surfaces of the frontal process and arch of the zygomatic bone, namely the incisura (Fig 1-4).

FIG 1-4 Drawing depicting the area of nasal elevation and the zygomatic bone after reflection and the incisura.

Although exposing the infraorbital rim is not necessary, exposing the infraorbital nerve is important because this nerve marks the boundary for the interior placement of two ipsilateral zygoma implants, when such an approach is required. To reduce cantilevering by increasing the posteroanterior separation of two ipsilateral implants, the clinician places the two implants so that their apices converge rather than lie parallel. Posterior implant placement is performed as close as possible to the posterior lateral wall of the maxillary sinus, and anterior implant placement is achieved as close anteriorly to the infraorbital nerves as safety will permit.

Retraction of soft tissues at the incisura (via careful placement of a zygoma retractor near the infraorbital rim) facilitates proper angulation of implants during placement. The zygoma implant platforms usually emerge in the region of the first molar or second premolar, unless an ipsilateral implant is required, in which case this will shift to the canine region.

The path of the implant is determined visually. The zygoma retractor provides a view of the targeted base of the zygomatic bone, and a straight measurement tool or drill bit can be laid across the lateral wall of the maxilla as a directional guidepost for drilling. Using a 105-degree handpiece with a round bur, the clinician penetrates the zygomatic bone regions for implant placement. To establish the final width of the implant site, the clinician first uses a 1-mm twist drill to pierce the cortices of the zygoma, followed by a 2-mm drill. An osteotomy depth gauge, which uses a hook to reach the superior cortex, measures osteotomy depth in 5-mm increments.

The implants are placed manually or with a handpiece. The clinician must prevent soft tissue from engaging the implant body and becoming embedded in the osteotomy, which may adversely affect osseointegration. The clinician should place the implant tip 2 mm past the superior cortex of the zygomatic bone, with the implant platform flush to the occlusal plane and as near the maxillary bone as possible. Next, the clinician retrieves the implant mount and places the cover screws. If two ipsilateral zygoma implants are placed, traditional implants may or may not be placed in the anterior maxilla for additional support. Finally, the clinician checks to ensure that bleeding has been controlled and applies copious irrigation before suturing with 3-0 polyglactin 910 (Vicryl, Ethicon).12,18,34

Surgical complications

Common complications involve unintended incursions into regions adjacent to the zygoma, namely the orbit and the temporal fossa (Fig 1-5). Incursions into the former are best avoided by the clinician’s correct use of the zygoma retractor in the incisura, ensuring a clear view of the region. Incursions into the temporal fossa result from an excessive posterior placement of the zygoma implant relative to the base of the bone; occasionally, the lack of adequate zygomatic bone can cause an incursion as well, particularly when ipsilateral implants are placed. Repositioning the implant bed anteriorly can remedy this complication.35–37

FIG 1-5 Proper zygoma implant placement is within the zygomatic bone and is generally kept within the temporal process of the zygomatic bone. Complications arise if incursions extend into the adjacent vital structures, including the orbit, temporal fossa, infraorbital foramen, infraorbital groove and fissure, or the zygomatic process.

Postoperative procedures

Clinicians familiar with postoperative procedures for implant placement into the maxilla accompanied by a sinus elevation will already be familiar with the procedures needed following the zygoma implant placement, namely safety measures related to the sinus, a soft food diet, and analgesic and antibiotic regimens.1,38,39

Postoperative complications

In addition to the kinds of postoperative complications associated with any dental implant procedure, the zygoma implant procedure has the additional concerns of a resulting oroantral communication and sinusitis. Sinusitis is a complication often associated with the intrasinus zygoma implant approach because it requires incursive surgery—a foreign body (the implant) placed in the sinus—possibly resulting in oroantral communication. Antibiotics and nasal decongestants are often the medical treatment of choice for sinusitis. However, a surgical remedy may be needed if medical treatment fails (eg, functional endoscopic sinus surgery, or FESS).9,40–42

Modified surgical procedures

A number of modified surgical approaches and procedures have been developed since Brånemark and colleagues pioneered the intrasinus approach in 1998.15,16 For example, using an extrasinus zygoma implant can reduce complications in the sinus while simultaneously optimizing buccal cantilevering, because the clinician avoids penetrating the maxillary sinus and what remains of the maxilla’s alveolar ridge24,34,43–45 (Fig 1-6).

FIG 1-6(a) Zygoma implant with roughened threads designed to engage both the zygomatic bone and the crestal alveolar bone being removed from its sterile packaging immediately prior to placement. (b) Placement of the first of four zygoma implants using an extrasinus approach with adequate flap reflection. (c) The second of the four zygoma implants in position. (d) All four of the zygoma implants in place and the hex oriented appropriately over the alveolar crest for prosthetics. (e) The flaps sutured back into position. (f) Radiographic appearance of the four zygoma implants in the maxilla and the four tilted implants in the mandible. (g) The transitional maxillary and mandibular prostheses in place.

Several specific modifications to the zygoma implant procedure have resulted in designated nomenclature. For example, the sinus slot technique does not require the creation of a sinus window, and it also optimizes the position of the zygoma implant.26,46 The sinus slot procedure provides for an increase in the vertical position of the zygoma implant as well as a superior buccal location of the implant platform. The crestal incision is shorter in this procedure, and the mucoperiosteal flap is raised to provide the clinician enhanced visibility. Additionally, the alveolar ridge is exposed via reflection of the palatal mucosa. The clinician creates a bur hole superiorly on the contour of the zygomatic buttresses as well as a bur hole on the alveolar ridge so that the apertures can be connected by a slot orienting the drilling for implant placement in the zygomatic bone. The result is good visibility of the implant during the procedure as well as superior bone-to-implant contact, because the implant intrusion into the sinus is correspondingly lessened, reducing complications.10

The zygoma anatomy-guided approach (ZAGA) to implant placement focuses on the creation of an optimal osteotomy site by emphasizing the two elemental structures of the procedure: the zygomatic bone anchor and the fixed prostheses themselves.47 The specific conditions of each patient’s edentulous maxilla guide the site preparation of the zygoma implant, obviating slot/window preparation of the lateral wall of the maxillary sinus. Optimal implant emergence on the alveolar ridge (for superior prosthetic performance) and the patient’s own zygomatic bone anatomy control implant length and apical placement. Thus, the points of emergence and apical placement determine whether the implant’s path is intrasinus, extrasinus, or some combination of the two.48–50

Conclusion

The zygoma implant procedure is generally safe, predictable, and cost-efficient. The literature continues to show that zygomatic bone anatomy and the anchoring systems designed to take advantage of that anatomy can guide the interdisciplinary surgical/restorative team in patient selection and patient-specific treatment planning. When maxillary implants cannot be used to restore the severely atrophied maxilla to function and esthetics, zygoma implants can often provide not only the means for efficient and effective anchoring of a prosthesis but also immediate function with fewer implants and a reduced treatment time. For these benefits, many patients are willing to undergo general or deep sedation for the procedure and to accept the risk of complications associated with a deep-anatomy implant failure.

References

1. Chana H, Smith G, Bansal H, Zahra D. A retrospective cohort study of the survival rate of 88 zygomatic implants placed over an 18-year period. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants 2019;34:461–470.

2. Aleksandrowicz P, Kusa-Podkańska M, Grabowska K, Kotuła L, Szkatuła-Łupina A, Wysokińska-Miszczuk J. Extra-sinus zygomatic implants to avoid chronic sinusitis and prosthetic arch malposition: 12 years of experience. J Oral Implantol 2019;45:73–78.

3. Butterworth CJ. Primary vs secondary zygomatic implant placement in patients with head and neck cancer—A 10-year prospective study [epub ahead of print 21 Jan 2019]. Head Neck doi: 10.1002/hed.25645.

4. Agliardi EL, Romeo D, Panigatti S, de Araújo Nobre M, Maló P. Immediate full-arch rehabilitation of the severely atrophic maxilla supported by zygomatic implants: A prospective clinical study with minimum follow-up of 6 years. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2017;46:1592–1599.

5. Araújo RT, Sverzut AT, Trivellato AE, Sverzut CE. Retrospective analysis of 129 consecutive zygomatic implants used to rehabilitate severely resorbed maxillae in a two-stage protocol. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants 2017;32:377–384.

6. Davó R, Pons O. 5-year outcome of cross-arch prostheses supported by four immediately loaded zygomatic implants: A prospective case series. Eur J Oral Implantol 2015;8:169–174.

7. Maló P, de Araújo Nobre M, Lopes A, Ferro A, Moss S. Extramaxillary surgical technique: Clinical outcome of 352 patients rehabilitated with 747 zygomatic implants with between 6 months and 7 years. Clin Implant Dent Relat Res 2015;17(suppl 1):e153–e162.

8. Yates JM, Brook IM, Patel RR, et al. Treatment of the edentulous atrophic maxilla using zygomatic implants: Evaluation of survival rates over 5–10 years. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2014;43:237–242.

9. Bedrossian E. Rehabilitation of the edentulous maxilla with the zygoma concept: A 7-year prospective study. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants 201;25:1213–1221.

10. Dechow PC, Wang Q. Evolution of the jugal/zygomatic bones. Anat Rec (Hoboken) 2017;300:12–15.

11. Dechow PC, Wang Q. Development, structure, and function of the zygomatic bones: What is new and why do we care? Anat Rec (Hoboken) 2016;299:1611–1615.

12. Vega L, Louis PJ. Zygomatic Implants. In: Haggerty CJ, Laughlin RM (eds). Atlas of Operative Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, 2015:42–47.

13. Van Steenberghe D, Malevez C, Van Cleynenbreugel J, et al. Accuracy of drilling guides for transfer from three-dimensional CT-based planning to placement of zygoma implants in human cadavers. Clin Oral Implants Res 2003;14:131–136.

14. Uchida Y, Goto M, Katsuki T, Akiyoshi T. Measurement of the maxilla and zygoma as an aid in installing zygomatic implants. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2001;59:1193–1198.

15. Brånemark PI, Gröndahl K, Ohrnell LO, et al. Zygoma fixture in the management of advanced atrophy of the maxilla: Technique and long-term results. Scand J Plast Reconstr Surg Hand Surg 2004;38:70–85.

16. Brånemark PI. Surgery and Fixture Installation: Zygomaticus Fixture Clinical Procedures, ed 1. Göteborg: Nobel Biocare AB, 1998.

17. Aparicio C, Manresa C, Francisco K, et al. Zygomatic implants: Indications, techniques and outcomes, and the zygomatic success code. Periodontol 2000 2014;66:41–58.

18. Sharma A, Rahul GR. Zygomatic implants/fixture: A systematic review. J Oral Implantol 2013;39:215–224.

19. Malevez C, Daelemans P, Adriaenssens P, Durdu F. Use of zygomatic implants to deal with resorbed posterior maxillae. Periodontol 2000 2003;33:82–89.

20. Yao J, Tang H, Gao XL, McGrath C, Mattheos N. Patients’ expectations to dental implant: A systematic review of the literature. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2014;12:153.

21. Pommer B, Mailath-Pokorny G, Haas R, Busenlechner D, Fürhauser R, Watzek G. Patients’ preferences towards minimally invasive treatment alternatives for implant rehabilitation of edentulous jaws. Eur J Oral Implantol 2014;7(suppl 2):S91–S109.

22. Peñarrocha M, Carrillo C, Boronat A, Martí E. Level of satisfaction in patients with maxillary full-arch fixed prostheses: Zygomatic versus conventional implants. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants 2007;22:769–773.

23. Aboul-Hosn Centenero S, Lázaro A, Giralt-Hernando M, Hernández-Alfaro F. Zygoma quad compared with 2 zygomatic implants: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Implant Dent 2018;27:246–253.

24. Coppedê A, de Mayo T, de Sá Zamperlini M, Amorin R, de Pádua APAT, Shibli JA. Three-year clinical prospective follow-up of extrasinus zygomatic implants for the rehabilitation of the atrophic maxilla. Clin Implant Dent Relat Res 2017;19:926–934.

25. Fortin Y. Placement of zygomatic implants into the malar prominence of the maxillary bone for apical fixation: A clinical report of 5 to 13 years. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants 2017;32:633–641.

26. Araújo PP, Sousa SA, Diniz VB, Gomes PP, da Silva JS, Germano AR. Evaluation of patients undergoing placement of zygomatic implants using sinus slot technique. Int J Implant Dent 2016;2:2.

27. Davó R, Felice P, Pistilli R, et al. Immediately loaded zygomatic implants vs conventional dental implants in augmented atrophic maxillae: 1-year post-loading results from a multicentre randomised controlled trial. Eur J Oral Implantol 2018;11:145–161.

28. Esposito M, Davó R, Marti-Pages C, et al. Immediately loaded zygomatic implants vs conventional dental implants in augmented atrophic maxillae: 4 months post-loading results from a multicentre randomised controlled trial. Eur J Oral Implantol 2018;11:11–28.

29. Neugarten J, Tuminelli FJ, Walter L. Two bilateral zygomatic implants placed and immediately loaded: A retrospective chart review with up-to-54-month follow-up. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants 2017;32:1399–1403.

30. Aparicio C. A proposed classification for zygomatic implant patient based on the zygoma anatomy guided approach (ZAGA): A cross-sectional survey. Eur J Oral Implantol 2011;4:269–275.

31. Balshi SF, Wolfinger GJ, Balshi TJ. A retrospective analysis of 110 zygomatic implants in a single-stage immediate loading protocol. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants 2009;24:335–341.

32. Davó R, David L. Quad zygoma: Technique and realities. Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am 2019;31:285–297.

33. Vega LG, Gielincki W, Fernandes RP. Zygoma implant reconstruction of acquired maxillary bony defects. Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am 2013;25:223–239.

34. Grecchi F, Bianchi AE, Siervo S, Grecchi E, Lauritano D, Carinci F. A new surgical and technical approach in zygomatic implantology. Oral Implantol (Rome) 2017;10:197–208.

35. Tuminelli FJ, Walter LR, Neugarten J, Bedrossian E. Immediate loading of zygomatic implants: A systematic review of implant survival, prosthesis survival and potential complications. Eur J Oral Implantol 2017;10(suppl 1):79–87.

36. Dawood A, Kalavresos N. Management of extraoral complications in a patient treated with four zygomatic implants. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants 2017;32:893–896.

37. Molinero-Mourelle P, Baca-Gonzalez L, Gao B, Saez-Alcaide LM, Helm A, Lopez-Quiles J. Surgical complications in zygomatic implants: A systematic review. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal 2016;21:e751–e757.

38. Salvatori P, Mincione A, Rizzi L, et al. Maxillary resection for cancer, zygomatic implants insertion, and palatal repair as single-stage procedure: Report of three cases. Maxillofac Plast Reconstr Surg 2017;39:13.

39. Sakkas A, Schramm A, Karsten W, Gellrich NC, Wilde F. A clinical study of the outcomes and complications associated with zygomatic buttress block bone graft for limited preimplant augmentation procedures. J Craniomaxillofac Surg 2016;44:249–256.

40. Chrcanovic BR, Albrektsson T, Wennerberg A. Survival and complications of zygomatic implants: An updated systematic review. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2016;74:1949–1964.

41. D’Agostino A, Trevisiol L, Favero V, Pessina M, Procacci P, Nocini PF. Are zygomatic implants associated with maxillary sinusitis? J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2016;74:1562–1573.

42. Bothur S, Kullendorff B, Olsson-Sandin G. Asymptomatic chronic rhinosinusitis and osteitis in patients treated with multiple zygomatic implants: A long-term radiographic follow-up. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants 2015;30:161–168.

43. Boyes-Varley JG, Howes DG, Lownie JF, Blackbeard GA. Surgical modifications to the Brånemark zygomaticus protocol in the treatment of the severely resorbed maxilla: A clinical report. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants 2003;18:232–237.

44. Migliorança RM, Sotto-Maior BS, Senna PM, Francischone CE, Del Bel Cury AA. Immediate occlusal loading of extrasinus zygomatic implants: A prospective cohort study with a follow-up period of 8 years. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2012;41:1072–1076.

45. Aparicio C, Ouazzani W, Aparicio A, et al. Extrasinus zygomatic implants: Three year experience from a new surgical approach for patients with pronounced buccal concavities in the edentulous maxilla. Clin Implant Dent Relat Res 2010;12:55–61.

46. Stella JP, Warner MR. Sinus slot technique for simplification and improved orientation of zygomaticus dental implants: A technical note. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants 2000;15:889–893.

47. Aparicio C, Manresa C, Francisco K, et al. Zygomatic implants placed using the zygomatic anatomy-guided approach versus the classical technique: A proposed system to report rhinosinusitis diagnosis. Clin Implant Dent Relat Res 2014;16:627–642.

48. Hung KF, Ai QY, Fan SC, Wang F, Huang W, Wu YQ. Measurement of the zygomatic region for the optimal placement of quad zygomatic implants. Clin Implant Dent Relat Res 2017;19:841–848.

49. Wang F, Monje A, Lin GH, et al. Reliability of four zygomatic implant-supported prostheses for the rehabilitation of the atrophic maxilla: A systematic review. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants 2015;30:293–298.

50. De Moraes PH, Olate S, Nóbilo Mde A, Asprino L, de Moraes M, Barbosa Jde A. Maxillary “All-On-Four” treatment using zygomatic implants. A mechanical analysis. Rev Stomatol Chir Maxillofac Chir Orale 2016;117:67–71.

Chapter 2

The ZAGA Concept: A Multifaceted Approach to Zygoma Implant Rehabilitation

Carlos Aparicio

Total or partial rehabilitation in patients with severely atrophic maxillae has always been a significant challenge for surgeons. Historically, the uncertainties involved in performing such a procedure have meant that many clinicians choose conventional methods even though they can be more costly, time-consuming, and complex for the patient. Yet the inadequate bone architecture of severely atrophic maxillae makes it difficult, if not impossible, to augment using standard protocols. But the learning curve for the placement of zygoma implants can be significant, even for highly experienced surgeons. Add to this the risk of late complications, and it is easy to see why clinicians are somewhat apprehensive when faced with the oral rehabilitation of a patient with a severely atrophic maxilla.

That said, most clinicians understand that patients with this condition are facing their last chance to receive a fully functioning set of teeth, recover esthetics, and regain masticatory function. Therefore, successful treatment is paramount.

After several initial reports on the possibility of using zygomatic anchorage for dental prosthetic fixation, mainly in discontinuous or severely atrophic jaws,1,2 in 2004 Brånemark et al3 presented the first long-term study on the results of using zygoma implants alone and in combination with bone grafts. The literature has since shown that zygoma implant placement according to this original procedure is predictable in terms of achieving implant and prosthesis stability. In 2009, Davó4 reported a 5 year retrospective study on two-stage loaded zygoma implants. Implant surfaces were pure machined titanium, and the 5-year survival rate was 98.5%. In 2010, Bedrossian5 reported a prospective follow-up of 36 patients followed for 5 to 7 years with an implant survival rate of 97.2%.

In a 3-year follow-up review, Goiato et al7 noted survival rates for zygoma implants of 97.9%, while a more comprehensive 12-year study carried out by Chrcanovic et al8 noted survival rates of 96.7%. No clear data was provided in either study on the frequency and type of complications, including sinusitis or soft tissue dehiscence. However, we know that complications are common in patients rehabilitated using zygoma implants. In fact, it can be speculated that sinusitis is present in 78% of cases when patients are rehabilitated using the original intrasinus technique and implants with rough-threaded surfaces.

The original Brånemark protocol for zygoma implant placement favored providing optimal implant stability over esthetic and prosthetic requirements. In this technique, one implant is placed into each zygoma with the starting point of the implant palatal to the area of the first molar and second premolar. To create an intrasinus path in the presence of a concave maxillary wall, the implant head is located on the palatal side of the alveolar bone. This typically leads to a bulky prosthesis, corresponding speech difficulties, and a hard-to-clean prosthesis. Additionally, in the atrophic maxilla, it is not uncommon for the palatal side of the alveolar bone or the sinus floor to be extremely thin. If, in the attempt to achieve an intrasinus path, the clinician crosses this thin layer of bone with a zygoma implant, it is very difficult to achieve and maintain a permanent osseous seal of the implant. At this point, the bone could be resorbed for several reasons, including connective tissue exposure or a patient history of periodontitis, smoking, poor hygiene habits, etc. Thus, if the thin bone surrounding the implant is resorbed when the implant penetrates the sinus, the seal will be weaker because it is based only on soft tissue. This can induce a late clinical or subclinical oroantral communication (Fig 2-1).

FIG 2-1(a) The intrasinus path of a zygoma implant 3 years after placement. Note the transparency of the maxillary sinus and the preservation of the palatal bone. (b) Tomographic slice of the same patient taken approximately 3 months later. The patient suddenly presented clinical and radiologic symptoms of acute sinus infection probably due to the appearance of an oroantral fistula.

To counteract the problem of an excessive implant head emergence at the palatal side and to reduce postoperative discomfort, Stella and Warner first described the slot technique in a technical report in 2000.9 In the report, they proposed making a narrow slot in the imagined direction of the implant, which would in theory assist in the visualization of the appropriate trajectory of the implant. The significant contribution of this concept was not the technique itself but the question it raised about the need for a palatal entry at all. Stella and Warner instead proposed a crestal entry to eradicate the problem of a bulky prosthesis and provide a smaller, more anatomical prosthesis.

The drawback of the slot technique is that it describes no means for avoiding oroantral communication when penetrating the sinus through an alveolar ridge that is too thin, nor is there a clearly defined implant pathway when faced with varying anatomical situations. Moreover, because the slot is created before implant placement, it does not always match the shape of the implant. In other words, the ability to seal the maxillary wall is limited. These problems led some clinicians to consider an extrasinus, or exteriorized, approach (Fig 2-2).

FIG 2-2(a) Simulation on a skeleton of the exaggerated palatal entry point that the osteotomy would require to achieve an intrasinus route in the case of extreme resorption and concavity of the maxillary wall. (b) Simulation on the same skeleton with an extramaxillary path.

The 1-year results of the extrasinus approach were first described in the English literature by Aparicio’s group in 200610 following their presentation at the 2005 Madrid meeting of the European Federation of Periodontology. The same year, Migliorança et al11 described a similar approach for zygomatic surgery that they called the exteriorized technique. Although the technique had fewer surgical steps, was less invasive, and was more precise because the implant matched the osteotomy, case photographs from Migliorança indicated that perforation of the sinus membrane near the crest was possible. As such, this technique poses the risk of sinus complications.

In a 3-year prospective study published in 2010, Aparicio et al12 reported the results of extrasinus placement of zygoma implants in 20 consecutive patients recruited from October 2004 to October 2005. The minimum follow-up period was at least 3 years. A total of 36 zygoma implants were used with smooth, machined titanium surfaces according to the initial zygomatic fixture design by Nobel Biocare. According to the authors, the indication for using the extrasinus approach was the presence of buccal concavities in the lateral wall of the maxillary sinus, which would cause an eventual intrasinus trajectory of the zygoma implants leading to the placement of the implant head at a distance greater than 10 mm from the center of the alveolar ridge. In these patients with very concave maxillary walls, the implant trajectory was prepared by drilling the alveolar crest sufficiently from its palatal side pointing toward the zygomatic arch, without making a previous window opening in the maxillary sinus. Priority was given to the anatomical prosthesis on the palatal entry, enabling the implant entry to occur at the maxillary ridge. Depending on the concavity of the wall, the implants had “aerial paths.” On the condition that an implant passed through a ridge sufficient in volume and architecture, the integrity of the sinus membrane was preserved, and the creation of a window or slot prior to surgery was eliminated.

In an extension of previous studies, Malo et al13 introduced a modified approach to suit all anatomies called the extramaxillary technique. However, it involved systematic contouring of the alveolar ridge to achieve exclusive anchorage into the zygomatic bone. As such, when patients presented with an over-contoured anterior maxillary sinus wall, the sinus membrane was inevitably perforated because it was in the direct pathway of the drill. Of the 18 patients who underwent a 1-year follow-up, 4 suffered sinus infections, representing a 22% rate of sinusitis.

In an in vitro study conducted by Corvello’s group,14 the paths of implants placed according to the original protocol were compared to those of implants placed with the exteriorized trajectory. The authors concluded that bone contact with the implant was greater in the exteriorized trajectory group and attributed this to the oblique penetration of the zygomatic bone that occurs when the implant path is extrasinus (Fig 2-3).

FIG 2-3(a) Simulation of an intrasinus path in a CBCT slice. The red arrow represents the size of the implant-bone contact. (b) Simulation of an extrasinus path in the same CBCT slice. The implant-bone contact, again represented by the red arrow, is greater when the path is externalized.14

All the previously described systems for the installation of zygoma implants—the original surgical procedure, the slot technique, and the extrasinus technique—promote a specific surgical method that should be universally applied to all patients. However, different morphologies of the edentulous maxilla have been identified, sometimes within the same individual. This led Aparicio in 2011 to describe the zygoma anatomy guided approach (ZAGA),15 based on a cross-sectional study and his own experiences with zygomatic rehabilitation over more than a decade. In essence, ZAGA is the evolved form of the previously described methods. The ZAGA concept provides a systematic approach to defining the trajectory of the zygoma implant—including the zygoma implant critical zone (ZICZ) as well as the entry/contact point on the alveolar crest and zygoma according to patient-specific anatomy. The objective of ZAGA is to tailor the procedure to each patient by adapting the osteotomy type to the specific anatomy of the patient. The surgical management of the implant site is guided by the anatomy of the patient according to specific prosthetic, biomechanical, and anatomical criteria. In most cases, late complications are prevented.15–23

What Is the ZAGA Concept?

ZAGA itself is described as a refinement or continuous evolution of the extrasinus technique. However, unlike methods that have gone before, ZAGA utilizes patient-specific therapies to achieve the best and most predictable outcomes while incorporating a combination of key criteria that define successful rehabilitation.

Central to this approach is the understanding that patients present with anatomical variations among themselves and even within the same mouth. Therefore, adapting the osteotomy type and the implant design to suit the individual patient is paramount.

Key criteria include the following:

• Identification of the patient’s anatomy according to the ZAGA classification

• Establishment of a prosthetic-driven implant trajectory including the ZICZ and the zygomatic anchoring zone (ZAZ)

• Selection of the appropriate osteotomy design (channel or tunnel shape)

• Selection of the appropriate implant design

• Adoption of appropriate procedures to avoid complications in each case

• Use of a systematic method to define success or failure in each case

Overall, the ZAGA concept provides clinicians with the necessary decision-making criteria to obtain satisfactory and predictable results. It also establishes protocols for determining the key landmarks, or ZAGA zones, that define the zygoma implant path. In this way, an individualized patient- and site-specific implant trajectory is established.

The ZAGA Zones

To facilitate the success of treatment, Aparicio et al22 identified the three main zones of the zygoma implant path (Fig 2-4):

•ZICZ: zygoma implant critical zone

•AZ: antrostomy zone

•ZAZ: zygomatic anchoring zone

FIG 2-4(a) Representation of the ZAGA zones: ZICZ (red), AZ (green), ZAZ (purple). (b) Note that the condition of the sinus is better 1 year later than at the time of surgery.

They also described anatomical characteristics of the zones and the best way to determine their positions.

The ZICZ is the complex formed by the maxillary bone, the soft tissues, and the zygoma implant at the coronal level.22 It is here where the first contact of the implant with the maxillary bone takes place. Correct positioning of the ZICZ is key in the ZAGA concept, and the maintenance of bone and soft tissues in the ZICZ should be a primary objective of the surgical approach.

The AZ is the area where the drill penetrates the maxillary sinus cavity. ZAGA recommends a minimally invasive collimated location of the AZ. No window or slot osteotomy/antrostomy is performed in the maxillary wall prior to implant placement. Depending on the maxillary anatomy, the antrostomy will be placed either on the inner aspect of the remaining alveolar bone (tunnel osteotomy in ZAGA types 0 and 1) or apical to the ZICZ when there is not enough alveolar bone to be traversed. In the latter case, the osteotomy trajectory is displaced buccally (ZAGA canal osteotomy types 2 and 4). Excluding ZAGA types 0 and 1, when the zygoma implant pierces the sinus floor through sufficient bone with adequate architecture, the AZ is usually located close to the zygomaticomaxillary suture. The location of the AZ will depend on the number and diameter of implants to be placed and the curvature of the zygoma buttress.

The ZAZ is the section of the zygomatic bone where the implant has maximum primary stability. The ZAGA concept uses a tangential path, thus increasing implant contact with the zygomatic bone. The implant usually passes through the four cortices of the maxillary zygomatic process to achieve optimal stabilization.

Rationale for ZAGA

As already stated, the learning curve for the placement of zygoma implants is very steep, even for those with significant experience in implant placement. In addition to the different tools required, zygoma implants are exceptionally long compared to conventional implants and correspond to completely different criteria for success. The surgeon requires an exceptional understanding of the anatomical structures as well as precise and accurate surgical skills. Additionally, the number of patients deemed suitable for this type of treatment in a conventional dental practice setting can be limited, meaning it takes longer to gain confidence and proficiency.

That said, once any inherent or potential risks are identified and the rationale for positioning the osteotomy is understood, the technical aspects of zygoma implant placement, including the optimal definition of the implant trajectory, can be mastered. Then the technique can become a standard advanced treatment modality in clinical practice.

In the end, the objectives for successful ZAGA implant placement are the following:

• To achieve optimal stability of the primary implant

• To achieve a prosthetic-driven implant trajectory, placing the implant head in the optimal restorative position

• To preserve as much bone as possible in the maxillary lateral wall and alveolar bone for optimal bone sealing and stability

• If possible, to maximize bone-to-implant contact along the implant by preparing an implant bed that includes the alveolar and zygomatic bone and the maxillary wall

•