Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Quintessence Publishing Co, Inc

- Kategorie: Fachliteratur

- Sprache: Englisch

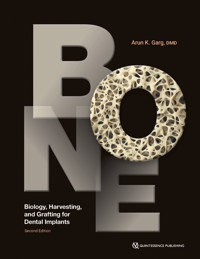

Dental implant placement often requires bone grafting to ensure sufficient bony support for the implants being placed. Depending on the biologic conditions of the patient, including the level of bone atrophy and the status of the remaining teeth in the mouth, more adjunctive procedures like bone harvesting or sinus grafting may be required. This book covers it all, from the biology of bone and how dental implants work within that framework to the many procedures for harvesting bone and using it to augment sites for implant placement. The different types of bone grafts and membranes are discussed as well as procedures to preserve the alveolar ridge following tooth extraction. Dr Garg was a pioneer in dental bone grafting, and this new edition keeps him at the forefront of the field.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 760

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

BONE

Biology, Harvesting, and Grafting for Dental Implants

Second Edition

One book, one tree: In support of reforestation worldwide and to address the climate crisis, for every book sold Quintessence Publishing will plant a tree (https://onetreeplanted.org/).

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Garg, Arun K., 1960- author.

Title: Bone biology, harvesting, and grafting for dental implants / Arun K. Garg.

Description: Second edition. | Batavia, IL : Quintessence Publishing Co, Inc, [2024] | Includes bibliographical references and index. | Summary: "Discusses the biology of bone and how dental implants work within that framework, demonstrates the many procedures for harvesting bone and using it to augment sites for implant placement, and describes the different types of grafts and membranes used during surgery to preserve or reconstruct the alveolar ridge"-- Provided by publisher.

Identifiers: LCCN 2023027515 | ISBN 9781647241704 (hardcover)

Subjects: MESH: Dental Implantation--methods | Bone Transplantation--methods | Bone and Bones--physiology

Classification: LCC RK667.I45 | NLM WU 640 | DDC 617.6/93--dc23/eng/20230703

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2023027515

A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN: 978-1-64724-170-4

© 2024 Quintessence Publishing Co, Inc

Quintessence Publishing Co, Inc

411 N Raddant Rd

Batavia, IL 60510

www.quintessence-publishing.com

5 4 3 2 1

All rights reserved. This book or any part thereof may not be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, or otherwise, without prior written permission of the publisher.

Editor: Leah Huffman

Design: Sue Zubek

Production: Sue Robinson

CONTENTS

Preface

01 Bone Biology and Physiology for Dental Implantology

02 Review of Bone Grafting Materials

03 Barrier Membranes for Bone Regeneration

04 Harvesting Bone from the Ramus

05 Harvesting Bone from the Mandibular Symphysis

06 Harvesting Bone from the Tibia

07 Bone Morphogenetic Proteins for Bone Regeneration

08 Alveolar Ridge Preservation After Tooth Extraction

09 Maxillary Sinus Grafting for Placement of Dental Implants

10 Augmentation and Grafting of the Maxillary Anterior Alveolar Ridge

11 Subnasal Elevation and Bone Augmentation

12 Grafting of the Nasopalatine Canal

13 Ridge-Spreading and Ridge-Splitting Techniques for Dental Implants

14 Membrane-Guided Bone Regeneration With and Without Cortical Bone Pins

15 Alveolar Ridge Grafting with Autogenous Bone Plates

16 Allogeneic Bone Plates for Bone Grafting

17 Titanium Mesh for Bone Regeneration

Index

PREFACE

Twenty years stand between publication of the first and second editions of BONE: Biology, Harvesting, and Grafting for Dental Implants. During this interval, the book garnered overwhelming acclaim from the professional community, as evidenced by multiple sold-out printings—a testament to its inherent academic and practical value.

At the inception of the first edition, resources in this field were sparse. Our pioneering effort filled a critical knowledge gap and has, over the years, proven its timelessness. The second edition maintains these core principles that resonated with so many, while also integrating advancements made over the last two decades. In certain chapters, little has changed, underscoring the validity of the initial procedures. Modifications in equipment and slight alterations in techniques have been meticulously documented. Alongside original photos, newer cases and images have been integrated to illustrate contemporary, albeit minor, shifts in techniques and tools.

We also debut entirely new chapters that spotlight techniques and procedures developed since the first edition. These additions, presented with up-to-date images and figures, offer readers an authentic glimpse into the evolution of contemporary practices in bone harvesting and grafting for dental implant surgery.

Our commitment to clarity and practicality remains unwavering. Each chapter meticulously delineates the biology, indications, and contraindications of respective procedures. Detailed step-by-step instructions enhance the book’s utility as a surgical manual, guiding readers toward mastery of the procedures.

Adding depth to this edition is the team behind it. The individuals who provided surgical assistance, engaged in critical discussions about procedures, and contributed in countless ways to the first edition are here again. Once my residents and fellows at the University of Miami School of Medicine in the Division of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, they have since risen to be recognized clinicians and esteemed university faculty worldwide. We continue to work together at our 30-chair mega implant clinic and training center. For over two decades, it has been my distinct honor and pleasure to collaborate with this same team. Our shared journey, centered on a common goal of elevating patient care through continuous learning and refining of surgical techniques, is distilled into this edition. The spirit of innovation, mentorship, and mutual growth that sparked the first edition continues to energize this one.

Throughout my 20-year tenure as a full-time surgeon and professor at the University of Miami Division of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, I have been privileged to perform countless innovative surgeries, collaborate with some of the brightest minds in the profession, and gain invaluable experience in teaching, publishing, and knowledge sharing.

As we unveil this second edition, our ambition remains twofold: to honor the past and illuminate the future. We trust that this edition will serve as a pivotal tool for dental professionals globally, echoing the success of its predecessor and further enriching the field of dental implant surgery.

01 Bone Biology and Physiology for Dental Implantology

The dental implant clinician must have a thorough understanding of bone structure and metabolism as well as osseointegration when placing bone grafts and implants. Many factors play a role in the healing and outcome of these procedures. For example, metabolism and aging directly affect the alveolar bone (primarily in the mandible), which forms intramembranously.1 Endochondral ossification, the type of bone development that begins embryonically, also occurs during bone healing after a fracture; therefore, it is possible that age is a factor in the rate of bone healing, particularly because fracture healing involves not only tissue revascularization but also cell differentiation and proliferation.

The first part of this chapter focuses on the clinical features of the skull and jaws overall, with specific references to dental and maxillofacial clinical practice: bone cells and metabolism, the macro/microscopic and molecular structure of bone, and bone modeling and remodeling. The second part of this chapter presents information specific to oral implantology: bone formation/modeling with bone grafts, osseointegration of dental implants, and autologous blood concentrates.

This general overview of the characteristics of human bone provides the necessary background and context for the chapters that follow, giving the dental surgeon a better appreciation of the role that bone plays in the success of dental implants.

The Human Skeleton: An Overview

The entire adult skeleton exists in a dynamic state, continually degenerating and regenerating via the coordinated action of osteoclasts and osteoblasts. Bone is a living tissue that serves two primary functions: structural support and calcium metabolism. The bone matrix is composed of an extremely complex network of collagen protein fibers impregnated with mineral salts that include mostly calcium phosphate, calcium carbonate to a much lesser degree, and very small amounts of calcium fluoride and magnesium fluoride. The minerals in bone are present primarily in the form of hydroxyapatites. Bone also contains small quantities of noncollagenous proteins embedded in its mineral matrix, including the all-important family of bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs). Coursing through the bone is a rich vascular network that provides perfusion to the viable cells as well as a network of nerves (Fig 1-1). Sufficient amounts of proteins and minerals must be present in the body for normal bone structure (Fig 1-2).

Fig 1-1(a and b) Bone cells maintain viability as a result of the rich arterial and venous supply, with smaller vessels reaching the cells embedded within the bone matrix. (c) The vascular system within the lamellar bone emerges from the medullary spaces; the interconnected design irrigates the entire structure.

Fig 1-2 Photomicrograph showing normal bone tissue.

Because of its unique architecture, bone is mass-efficient, meaning that maximal strength is achieved with minimal mass (Fig 1-3). In humans, bone mass reaches its maximum level approximately 10 years after the end of linear growth. This level normally remains fairly constant, as bone is continually deposited and absorbed throughout the skeleton until sometime in the fourth decade of life, when a gradual decline in bone mass begins to occur. Although the reasons are not clearly understood, this decline is a result of an ongoing net loss in the bone remodeling process. By age 80 years, both men and women typically have only about half of their maximum bone mass value. Humans reach peak bone mineral density in their 30s, although the density is lower in women than in men and in whites than in blacks. Women lose an estimated 35% of their cortical bone and 50% of their cancellous bone as they age, while men lose only two-thirds of these amounts.2 Bone deemed unnecessary by the body (such as in paraplegic individuals) is also lost during a shift in the absorption-deposition balance in bone remodeling. In addition, turnover may be a response to metabolic reactions.

Fig 1-3 Bone, a mass-efficient tissue, has a trabecular configuration that provides resilience under functional load.

Bone cells

Mesenchymal stem cells differentiate into the three main types of cells that are involved in bone metabolism and physiology: osteoblasts, osteocytes, and osteoclasts (see Fig 1-12). Osteoblasts, which are located in two general areas, deposit bone matrix (Fig 1-4) and are referred to as either endosteal osteoblasts or periosteal osteoblasts. Periosteal osteoblasts are present on the outer surfaces of the bones beneath the periosteum, while endosteal osteoblasts line the vascular canals within bone (Fig 1-5). Mature osteoblasts are responsible for producing the proteins of bone matrix. Indeed, the cytoplasm of osteoblasts is intensely basophilic, suggesting the presence of ribonucleoproteins that are related to the synthesis of these protein components. Bone deposition continues in an active growth area for several months, with osteoblasts laying down new bone in successive layers of concentric circles on the inner surfaces of the cavity in which they are working. This activity continues until the tunnel is filled with new bone to the point that the new growth begins to encroach on the blood vessels running through it. In addition to mineralizing newly formed bone matrix, osteoblasts also produce other matrix constituents, such as phospholipids and proteoglycans, which may also be important in the mineralization process. During osteogenesis (Fig 1-6), the osteoblasts secrete growth factors, including transforming growth factors such as transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β), BMPs, platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF), and insulin-like growth factors (IGFs), which are stored in bone matrix. Some research suggests that osteoblasts may even act as helper cells for osteoclasts during normal bone resorption, possibly by preparing the bone surface for their attack.3,4 However, further study is needed to clarify this possible role.

Fig 1-4 Osteoblasts originate from mesenchymal stem cells. Uninuclear and cuboidal in structure, they form osteoid and transform into osteocytes.

Fig 1-5 Endosteal osteoblasts line the vascular canals within bone.

Fig 1-6 Bone remodeling consists of three consecutive phases: (1) resorption, during which osteoclasts digest old bone; (2) reversal, when mononuclear cells appear on the bone surface; and(3) formation, when osteoblasts lay down new bone until the resorbed bone is completely replaced. The osteoblasts secrete growth factors such as insulin-like growth factors (IGFs), prostaglandins, transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β), BMPs, and cytokines.

When osteoblasts have successfully formed bone matrix and then become embedded in it, they transform into osteocytes (Fig 1-7). Osteocytes are the most abundant type of bone cells, and they communicate with each other and with cells on the bone surface via dendritic processes encased in canaliculi. Osteocytes have a slightly basophilic cytoplasm, the prolongations of which extend from the osteocyte through a network of fine canaliculi that emerge from the lacunae. During bone formation, these prolongations extend beyond their normal limit, creating direct continuity with adjacent osteocyte lacunae and with the tissue spaces (Fig 1-8). Fluid in these spaces mixes with fluid from the canaliculi; this mixing appears to allow an exchange of metabolic and biochemical messages between the bloodstream and osteocytes. In mature bone, there is almost no extension of these prolongations, but the canaliculi continue to function as a means of messenger exchange. This mechanism allows the osteocytes to remain alive, regardless of the calcified intercellular substance surrounding them. However, this duct system does not function if it is located more than 0.5 mm from a capillary, which may explain the abundant blood supply in bone through capillaries that run through the Haversian systems and Volkmann canals (Fig 1-9). Osteocytes have also been shown to express TGF-β and possibly other growth factors. Weight-bearing loads may influence the behavior of bone remodeling cells located on bone surfaces by their effects on the osteocytes buried within the bone, which subsequently release TGF-β into the canalicular system. Additionally, osteocytes may play a role in transporting calcium through the bone.

Fig 1-7 Osteocytes are architects of bone.

Fig 1-8 Microcanalicular structure of bone, longitudinal section. (Extracted with ethylenediamine acetate; spaces infused with vinyl acetate.)

Fig 1-9 No cell is buried in matrix more than 300 µm from a blood vessel to ensure nutrition.

Osteoclasts are the cells responsible for bone resorption, and their activity is controlled by parathyroid hormone. Osteoclasts are fused monocytes that histologically appear as large, multinucleated giant cells (containing as many as 50 nuclei). They are located in shallow excavations (Howship lacunae) along the mineralized bone surfaces. A specific area of their cell membrane forms adjacent to the bone surface to be resorbed. This area, known as the ruffled border, is formed by villus-like projections that the osteoclasts send out toward the bone. It consists of folds and invaginations that allow intimate contact between the cell membrane and the bone surface (Fig 1-10). Bone resorption occurs in the ruffled border as the villi secrete proteolytic enzymes that digest or dissolve the organic bone matrix and acids that cause dissolution of the bone cells. Via phagocytosis, osteoclasts also absorb minute particles of bone matrix and crystals, eventually dissolving them and releasing their products into the bloodstream. In adults, osteoclasts are usually active on less than 1% of bone surfaces at any one time.5 They typically exist in small but concentrated masses. Once a mass has developed, it usually dissolves the bone for about 3 weeks, creating a tunnel that ranges from 0.2 to 1.0 mm in diameter and several millimeters in length. After local bone resorption is complete, the osteoclasts disappear, probably by degeneration. Subsequently, the tunnel is invaded by osteoblasts, and the bone formation segment of the continuous remodeling cycle begins again.

Fig 1-10 Osteoclasts are multinucleated cells that specialize in bone matrix resorption.

In addition to the three main types of bone cells, there is a fourth type: the bone lining cell (Fig 1-11). These cells are similar to osteocytes in that they are “retired” osteoblasts—in other words, osteoblasts that do not become embedded in newly formed bone but instead adhere to the outer bone surfaces when formation halts. Bone lining cells become quiescent and flattened against the bone surface, but they do not form a contiguous gap-free barrier. They maintain communication with osteocytes and with each other via gap-junctioned processes, and they also appear to maintain their receptors for hormones such as parathyroid hormone and estrogens. As with osteocytes, bone lining cells are thought to play a role in transferring mineral into and out of bone and in sensing mechanical strain. They may also initiate bone remodeling in response to various chemicals or mechanical stimuli.

Fig 1-11 Bone lining cells are thought to play a role in transferring mineral into and out of bone and in sensing mechanical strain. They may also initiate bone remodeling in response to various chemicals or mechanical stimuli.

Bone metabolism

Bone is the body’s primary reservoir of calcium. Its tremendous turnover capability allows it to respond to the body’s metabolic needs and to maintain a stable serum calcium level. Calcium has an essential life-support function. It works in conjunction with the lungs and kidneys to help maintain the body’s pH balance by producing additional phosphates and carbonates. It also assists in the conduction of nerve and muscle electrical charges, including those involving the heart.

Bone structure and mass throughout the body, including the structure and mass of bone in the skull and jaws, are directly affected by the body’s metabolic state. Faced with unmet calcium requirements or certain diseases, the structural integrity of bone may be altered and even compromised. Consider the bone structure of postmenopausal women. In response to decreased estrogen hormone in the system, bone mass begins to dwindle, and the interconnections between bone trabeculae are lost. Because normal interconnections are crucial for making bone biomechanically rigid, the decrease in bone leads to an increase in fragility. This is an important phenomenon in dental implantology and related bone grafting because it would seem to suggest that declining estrogen levels would increase the risk of implant failure.6 However, studies suggest that neither osteoporosis7 nor menopausal status8 in and of themselves are contraindications for dental implant placement.

The effects of a disrupted balance in bone remodeling are illustrated by Albers-Schönberg disease, or “marble bone” disease, which involves defective osteoclasts. Because these osteoclasts do not resorb the existing bone matrix and liberate BMPs, new bone is not formed, resulting in avascular and acellular bone (essentially, old bone) that is brittle and thus fractures easily and becomes infected. Other diseases associated with bone remodeling abnormalities include cancer, primary hyperparathyroidism, and Paget disease. Although these disorders are common, in most cases little is known about what mechanisms are responsible for controlling normal bone remodeling or how it is coordinated and balanced.

Metabolic-hormonal interactions play a crucial role in maintaining bone structure. Most importantly, they help to maintain the coupled cycle of bone resorption and bone apposition through BMPs. As previously noted, when osteoblasts form bone, they also secrete BMPs into the mineral matrix. These acid-insoluble proteins reside in the matrix until they are released during osteoclastic resorption. This acid insolubility is an evolutionary mechanism by which these proteins can withstand the pH of 1 created by osteoclasts to dissolve bone mineral. Once released, BMPs bind to the surfaces of undifferentiated mesenchymal stem cells, where they cause a membrane signal protein to become activated with high-energy phosphate bonds. This, in turn, affects the gene sequence in the nucleus, causing expression of osteoblast differentiation and stimulation of new bone production (Fig 1-12). A disruption of this process may be at the root of osteoporosis. Of current research interest is the therapeutic potential of applying BMPs directly to a healing site to induce bone formation. Some researchers suggest that, in the future, this biologic material may replace or assist bone grafts in restorative therapy.9

Fig 1-12 When influenced by the TGFs secreted by platelets and osteoblasts, undifferentiated stem cells can transform into pre-osteoblasts, then osteoblasts, and eventually osteocytes, thus maturing into the tissues essential to the body.

Normally, about 0.7% of the human skeleton is resorbed and replaced by new, healthy bone each day. Therefore, normal turnover of the entire skeleton occurs approximately every 142 days (Fig 1-13). With aging and metabolic disease states, there may be a reduction in the normal turnover process and thus an increase in the average age of functional bone. This raises the risk for fatigue damage of old bone, compromised bone healing, failed implant integration, and loss of implant osseointegration. Thus, it is important for dental surgeons to recognize that a compromised status must be considered before treatment planning because its effects may not be revealed until the clinician attempts to place implants or until the implants have been in place for some time.

Fig 1-13 Normal turnover of the entire skeleton occurs approximately every 142 days. With aging and metabolic disease states, there may be a reduction in the normal turnover process and thus an increase in the average age of functional bone.

Macroscopic structure of bone

The human skeleton is composed of two distinct kinds of bone based on porosity: dense cortical tissue and spongy cancellous tissue (Fig 1-14). In principle, the porosity of bone could vary continuously from 0% to 100%; however, most sites are either of very low or very high porosity. In most cases, both cortical and cancellous tissues are found at every bone site, but their quantity and distribution vary. The nonmineralized spaces within bone contain marrow, a tissue consisting of blood vessels, nerves, and various cell types. Marrow’s chief function is to generate the principal cells present in blood; it is also a highly osteogenic material that can stimulate bone formation if placed in an extracellular skeletal location, as with bone grafting in the dental area.

Fig 1-14 The ratio of cortical to cancellous bone in the mandible and maxilla varies among individuals, but the vast majority of total bone in the body is cortical bone.

Cortical or compact bone, which comprises the vast majority of total bone in the body, is found in the shafts of long bones and forms a shell around vertebral bodies and other spongy bones. This tissue is organized in bony cylinders consolidated around a central blood vessel, called a Haversian system. Haversian canals, which contain capillaries and nerves, are connected to each other and to the outside surfaces of the bone by short, transverse Volkmann canals (Fig 1-15).

Fig 1-15 Microcanalicular structure of bone. The walled Haversian system is interconnected with Volkmann canals.

Trabecular (cancellous) bone, which comprises about 15% of the body’s total bone, is found in cuboidal and flat bones and in the ends of long bones. Its pores are interconnected and filled with marrow. The bone matrix is in the form of plates (called trabeculae) arranged in a varied fashion; sometimes they appear to be organized into orthogonal array, but often they are randomly arranged (Fig 1-16). The medullary cavities are filled with marrow (Fig 1-17), which is red when there is active production of blood cells or a reserve population of mesenchymal stem cells and yellow when aging causes the cavity to be converted into a site for fat storage.

Fig 1-16 Cancellous bone has several unique properties. Beams and struts of mineralized bone are covered by osteoid tissue with osteoblasts. Large beam-like pieces are known as trabeculae, and smaller strut-like pieces are known as spicules. The axis of trabeculae is usually at 90 degrees to deformation forces. Trabeculae surfaces are covered by nonmineralized osteoid.

Fig 1-17 In cancellous bone, the structures are obscured by either red or yellow (fatty) bone marrow.

Except for the articular surfaces, the outer surface of bone is covered with periosteum, which forms a boundary between the hard tissue and its soft tissue covering. It is also the site of considerable metabolic, cellular, and biomechanical activities that modulate bone growth and shape (Fig 1-18). The periosteum is composed of two layers of specialized connective tissue. The outer fibrous layer, mainly formed from dense collagenous fibers and fibroblasts, provides toughness while the inner cellular (cambium) layer, which is in direct contact with bone, contains functional osteoblasts. The medullary cavities and spaces are covered by endosteum, a very thin and delicate membrane consisting of a single layer of osteoblasts. The endosteum is architecturally similar to the cambium layer of the periosteum because of the presence of osteoprogenitor cells, osteoblasts, and osteoclasts.

Fig 1-18 The periosteum, a connective tissue membrane surrounding cortical bone, should be carefully repositioned so that its osteogenic potential after surgery can nurture the graft and/or underlying bone.

Microscopic structure of bone

At the microscopic level, there are four types of bone: woven, composite, lamellar, and bundle. Woven bone plays a principal role in healing because it forms very quickly (approximately 30 to 60 mm/day). As a result, it develops in a very disorganized fashion, without lamellar architecture or Haversian systems. Thus, it is quite soft, biomechanically weak, and short-lived. On the plus side, however, woven bone can become more highly mineralized than lamellar bone, a fact that, mechanically speaking, may help to compensate for its lack of organization. During healing, woven bone is often referred to as phase I bone. It is fairly quickly resorbed and replaced with more mature lamellar bone (phase II bone). Composite bone refers to the transitional state between phase I bone and phase II bone, in which a woven bone lattice filled with lamellar bone can be detected.

Lamellar bone is the most abundant, mature, load-bearing bone in the body. This type of bone forms slowly (approximately 0.6 to 1 mm/day) and thus has well-organized collagen protein and mineralized structure. Lamellar bone consists of multiple oriented layers. Bundle bone is the principal bone found around ligaments and joints, and it consists of striated interconnections with ligaments.

Bone’s mechanical viability and fragility depend to a certain degree on the structure and microstructure of the cortical bone compartment (Fig 1-19). Beyond bone mineral density and bone mineral content, additional features of cortical bone contribute to whole bone’s resistance to fracture. Structural properties of cortical bone most commonly employed as surrogate for its mechanical competence include thickness of the cortex, cortical cross-sectional area, and area moment of inertia.

Fig 1-19 Both the structure and the microstructure of cortical bone contribute to the mechanical competence and fragility of the whole bone.

But microstructural properties, such as cortical porosity, crystallinity, or the presence of microcracks, also influence bone’s mechanical competence. Microcracks in particular not only weaken the cortical bone tissue but also provide an effective mechanism for energy dissipation. Bone is a damageable, viscoelastic composite, living material capable of self-repair. As a result, it demonstrates a complex series of mechanical properties. For the implantologist, a direct correlation exists between the science of cortical bone and microcracks/microdamage and the kinds of damage that can occur when tapered and cylindric implants are placed after pilot drilling.10 Implant osteotomy preparation that avoids microdamage can directly affect initial implant stability and bonehealing/osseointegration.11

One feature largely disregarded in the diagnosis of bone diseases and fracture risk assessment is the contribution of cortical bone quantity and quality. Cortical bone carries a considerable share of the total load of the skeleton. Biomechanical studies demonstrate that the structural behavior of whole bone specimens is highly determined by the contribution of cortical bone. In biomechanics, a distinction is usually made between the mechanical (material) behavior of bone tissue and the mechanical (structural) behavior of the entire bone. Bone’s mechanical competence reflects both the geometry (size and shape) and the intrinsic material properties (elasticity, strength, and toughness). Because of the complexity of the bone failure mechanism, it is not clear which properties account for bone fragility. Toughness, or energy to failure, a tissue property pertaining to the capability of bone tissue to absorb energy during the failure process, is likely a dominant determinant of fracture risk. From a mechanical perspective, it is evident that the rigidity and strength of a structure are determined not only by the amount of material but even more importantly by the arrangement of the material in space.

Haversian canals and resorption cavities in cortical bone produce a porous bone tissue with pore diameters ranging from a few to up to several hundred micrometers. Morphometry and biomechanical testing have perceived strong correlations between intracortical porosity and cortical bone material properties. The number and size of the pores determine intracortical porosity, which accounts for about 70% of elastic modulus and 55% of yield stress.12 Local measurements of bone mineral density in cortical bone specimens corroborate these findings.13 Fracture toughness also decreases with increasing porosity, possibly by reducing the available area for the propagation of microcracks.14

Molecular structure of bone

At the molecular level, bone is composed of collagen (primarily type 1), water, hydroxyapatite (HA) material, and small amounts of proteoglycans and noncollagenous proteins (Fig 1-20). It is a cross-linked collagen matrix with a 3D multiple arrangement of matrix fibers. The orientation of the collagen fibers determines the mineralization pattern. In this way, bone adapts to its biomechanical environment and projects maximal strength in the direction receiving compressive loads. Collagen gives bone tensile strength and flexibility and provides a place for the nucleation of bone mineral crystals, which give bone its rigidity and compressive strength.

Fig 1-20 At the molecular level, bone is composed of collagen (primarily type 1), water, HA material, and small amounts of proteoglycans and noncollagenous proteins.

The intercellular bone substance has an organized structure. The organic portion occupies 35% of the matrix and is primarily formed by osteocollagenous fibers, similar to collagen fibers in connective tissue. These are joined together by a cement-like substance that consists primarily of glycosaminoglycan (protein-polysaccharide). The inorganic component of bone comprises 65% of bone weight and is localized only in the interfibrous cement. The minerals in bone consist mainly of HA crystals, which form deposits along the osteocollagenous fibers. Bone also contains other substances, such as carbonate, fluoride, other proteins, and peptides. Some of these materials are governed by the body fluid composition and affect the solubility of bone mineral.

Other components, such as BMPs, regulate how bone is laid down and maintained. Bone matrix has sequential lamellae that vary in thickness from 300 to 700 μm. These layers are the result of rhythmic and uniform matrix deposition. Also characteristic is the pattern of fibers within each layer, which are parallel and exhibit a spiral orientation that changes between layers so that the fibers in one layer run perpendicular to those in the adjacent layer. This pattern creates the distinguishable layers in bone.

Bone modeling and remodeling

As noted above, bone is continually being deposited by osteoblasts and absorbed by osteoclasts at active sites in the body. In adults, a small amount of new bone is continually being formed by osteoblasts, which work on about 4% of all surfaces at any given time. Although many orthopedists and bone scientists refer to both processes as remodeling, it is important to note that bone modeling involves two different processes in osseous repair. Bone modeling typically refers to the sculpting and shaping of bones after they have grown in length. This process involves the independent, uncoupled actions of osteoclasts and osteoblasts, so bone is resorbed in some areas and added in others. Bone modeling can also be controlled by mechanical factors—for example, during orthodontic tooth movement, in which the application of force causes the bone to resorb on the tooth surface, new bone to form on the opposite surface, and the tooth to move with the surrounding bone rather than through the alveolus. Bone modeling can change both the size and shape of the bones.

Bone remodeling, on the other hand, refers to the sequential, coupled actions by these two types of cells (see Fig 1-11). It is a cyclical process that usually does not change the size or shape of bones. Bone remodeling removes a portion of old bone and replaces it with new bone. Unlike bone modeling, which slows substantially after growth stops, bone remodeling occurs throughout life (although its rate also slows somewhat after growth). Bone remodeling also occurs throughout the skeleton in focal, discrete packets that are distinct in location and chronology. This characteristic of remodeling suggests that the activation of the cellular sequence responsible for bone remodeling is controlled locally, possibly by an autoregulatory mechanism, such as autocrine or paracrine factors generated in the bone microenvironment.

Bone modeling also occurs during wound healing (for example, during the stabilization of endosseous implants) and in response to bone loading. Unlike bone remodeling, bone modeling does not have to be preceded by resorption. The activation of cells that resorb and of those that form bone can occur on different surfaces within the same bone. In addition, bone modeling may also be controlled by growth factors, as in bone healing, grafting, and implant osseointegration. Whether bone is being modeled or remodeled, it is deposited in proportion to the compressional load it must carry. For instance, the bones of athletes become considerably heavier than those of nonathletes. Likewise, a person with one leg in a cast who continues to walk using only the opposite leg will experience a thinning of the unused leg bone.

Continuous physical stress stimulates osteoblastic activity and calcification of bone. Bone stress also determines the shape of bones in some circumstances. It has been theorized that bone compression causes a negative electrical potential in the compressed area and a positive electrical potential elsewhere in the bone. Minute amounts of electric current flowing in bone have been shown to cause osteoblastic activity at the negative end of the current flow, which may explain increased bone deposition in compression sites. This effect is the basis of studies on the use of electrical stimulation to promote bone formation and osseointegration, though further research is needed to support claims of benefit.15

Dental Implantology: Bone Structure, Metabolism, and Physiology

When placing implants in the mandible or maxilla, surgeons must understand the process of bone remodeling, the different types of bone and where each is present in the jaws, and how these factors can affect the integration of osseous dental implants. Approximately 0.7% of a human skeleton is resorbed daily and replaced by new, healthy bone. With aging and metabolic disease states, the normal turnover process may be reduced, resulting in an increase in the mean age of the present bone. This increase can affect the placement and integration of implants.

Bone formation and modeling with bone graft materials

In most cases, the goal of placing a bone graft in dentistry is to regenerate lost tissue as well as simply to repair or fill the defect.16,17 Bone grafting is recommended around implants placed in sites where bone volume or density is deficient or where there is a history of implant failure. To achieve optimal results, an osseointegration period of 3 to 6 months prior to loading is recommended for implants placed in native bone or grafted bone, depending on bone density and healing of the grafted site. While no definitive conclusions have been reached on the superiority of native or grafted bone to support the placement of dental implants, when rehabilitating reconstructed jaws, the surgeon may prefer to place implants in grafted bone rather than in normal bone, depending on patient general health and lifestyle (for example, smoking habits). A mid-1990s review of head and neck cancer patients suggested that grafted bone integrates with implants to a higher degree than natural host bone.18 This was also the conclusion reached by researchers in a 2009 study involving osseous onlay grafts and native bone.19 However, a more recent (2011) study of irradiated head and neck cancer patients found no significant difference in implant survival rates between native and grafted bone,20 as did a 2016 study of over 1,200 patients not suffering from cancer.21 A separate 2016 study concluded that nongrafted sites were by far the optimal environment for implant integration.22

There are four basic types of bone graft materials (Fig 1-21), each associated with specific advantages and drawbacks (Table 1-1): autogenous (or autografts), allogeneic (or allografts), xenogeneic (xenografts), and alloplasts. An autogenous bone graft is the transfer of tissue from one part of a patient’s body to another. An autograft is considered the gold standard in bone grafting for two reasons: (1) the graft is made of living tissue, which facilitates osteogenesis; and (2) the graft carries no risk of host rejection or contamination. The two main drawbacks of an autograft are the need to harvest the bone and hence a second surgical site (and potential morbidity), and limited bone supply. In descending order of cancellous bone availability, autogenous donor sites include the posterior and anterior ilium, tibial plateau, femoral head, mandibular symphysis, calvaria, rib, and fibula. Other intraoral sites, such as the mandibular ramus, may also be a good choice for autogenous bone harvesting.

Fig 1-21 The four different types of bone graft materials have different properties that make them more or less useful under specific conditions.

Table 1-1 Properties of various types of bone graft sources

Osteoconductive

Osteoinductive

Osteogenic

Alloplast

+

–

–

Xenograft

+

–

–

Allograft

+

+

±

Autograft

+

+

+

A bone allograft is tissue obtained from a human cadaver that has been processed and sterilized by an accredited tissue bank. Allografts have some of the advantages that autografts lack, such as unlimited supply without the requirement of a second surgical site. The two drawbacks of using a bone allograft are the theoretical risk of a host immune response to the graft and its lower level of osteogenicity, which results in slower bone growth and a reduced volume compared with autografts.

A bone xenograft is bone tissue transplanted from a different species. Most bone xenografts used in dentistry are of bovine or porcine origin and have been treated to facilitate safe, effective use in humans. A xenograft serves as a matrix onto which adjacent recipient bone can grow. It facilitates minimal bone repair via osteoconduction as it lacks properties to stimulate new bone growth.

A bone alloplast is a synthetic bone substitute such as bioactive glass, calcium sulfate, HA, and calcium phosphate. Synthetic bone heals minimally through osteoconduction.23–26

The ideal graft material should transfer an optimal number of viable osteocompetent cells—including osteoblasts and cancellous marrow stem cells—to the host site. For successful osseointegration of the implant into the grafted site, the host tissue must have sufficient vascularity to diffuse nutrients to the cells before revascularization occurs and to bud new capillaries into the graft to create a more permanent vascular network (Fig 1-22). Thus, depending on the amount of new bone needed, donor sites are selected based on their osteocompetent cell density. The graft also consists of islands of mineralized cancellous bone, fibrin from blood clotting, and platelets within the clot (Fig 1-23).

Fig 1-22 Autogenous cancellous bone grafts have large quantities of osteocytes, osteoblasts, and osteoclasts, while the recipient site provides vascularity and cells.

Fig 1-23 An autogenous bone graft contains fibrin, platelets, leukocytes, and red blood cells. The platelets release growth factors that trigger bone regeneration.

Placement of a graft that consists of endosteal osteoblasts and marrow stem cells into a vascular and cellular tissue bed creates a recipient site with a biochemistry that is hypoxic (O2 tensions of 3 to 10 mm Hg), acidotic (pH of 4.0 to 6.0), and lactate-rich. The osteoblasts and stem cells survive the first 3 to 5 days after transplant to the host site largely because of their surface position and ability to absorb nutrients from the recipient tissues. The osteocytes within the mineralized cancellous bone die as a result of their encasement in mineral, which acts as a nutritional barrier. Because the graft is inherently hypoxic and the surrounding tissue is normoxic (50 to 55 mm Hg), an oxygen gradient greater than 20 mm Hg (usually 35 to 55 mm Hg) is established and, in turn, the macrophages are stimulated to secrete macrophage-derived angiogenesis factor (MDAF) and macrophage-derived growth factor (MDGF).

Within the graft, the platelets trapped in the clot degranulate within hours of graft placement, releasing PDGF. Consequently, the inherent properties of the wound—particularly the oxygen gradient phenomenon and PDGF—initiate early angiogenesis from the surrounding capillaries and mitogenesis of the transferred osteocompetent cells. By day 3, buds from existing capillaries outside the graft can be detected. These buds penetrate the graft and proliferate between the graft and the cancellous bone network to form a complete network by days 10 to 14. As these capillaries respond to the oxygen gradient, MDAF messengers effectively reduce the oxygen gradient as they perfuse the graft, thus creating a shut-off mechanism that prevents over-angiogenesis.

Although PDGF seems to be the earliest messenger to stimulate early osteoid formation, it is probably replaced by MDGF and other mesenchymal tissue stimulators from the TGF-β family. During the first 3 to 7 days after graft placement, the stem cells and endosteal osteoblasts produce only a small amount of osteoid (Fig 1-24). Over the next few days, osteoid production accelerates after the vascular network is established, presumably because of the availability of oxygen and nutrients. The new osteoid initially forms on the surface of the mineralized cancellous trabeculae from the endosteal osteoblasts. Shortly thereafter, individual osteoid islands develop between the cancellous bone trabeculae, presumably from the stem cells transferred with the graft material. A third source of osteoid production is circulating stem cells, which are attracted to the wound and are believed to seed into the graft and proliferate.

Fig 1-24 Schematic representation of bone graft incorporation.

During the first 3 to 4 weeks, this biochemical and cellular phase of bone regeneration coalesces individual osteoid islands, surface osteoid on the cancellous trabeculae, and host bone to clinically consolidate the graft. This process uses the graft’s fibrin network as a framework to build upon via osteoconduction. Normally nonmotile cells, such as osteoblasts, may be somewhat motile via the process of endocytosis along the scaffold-like fibrin. During endocytosis, the cell membrane is transferred from the retreating edge of the cell, through the cytoplasm, to the advancing edge to re-form a cell membrane. The cell slowly advances and secretes its product along the way—in this case, osteoid onto the fibrin network.27,28 This cellular regeneration phase is often referred to as phase I bone regeneration. It produces disorganized woven bone, similar to fracture callus, that is structurally sound but not as strong as mature bone. The amount of bone formed during phase I depends on the osteocompetent cell density in the graft material. The surgeon can enhance the bone yield by compacting the graft material using a bone mill, followed by syringe compaction, and then by further condensing it into the graft site with bone-packing instruments.

Phase I bone undergoes resorption and remodeling, until it is eventually replaced by phase II bone, which is less cellular, more mineralized, and more structurally organized. Phase II is initiated by osteoclasts that arrive at the graft site through the newly developed vascular network. BMPs are released during resorption of both the newly formed phase I bone and the nonviable cancellous trabecular graft. As with normal bone remodeling, BMPs act as the link or couple between bone resorption and new bone apposition. Stem cells in the graft and from the local tissues and the circulatory system respond by osteoblast differentiation and new bone formation. New bone forms while the jaw and graft are in function, developing in response to the demands placed on it. This bone develops into mature Haversian systems and lamellar bone that can withstand normal shear forces from the jaw and impact compressive forces that are typical of dentures and implant-supported prostheses. Histologically, grafts undergo long-term remodeling that is consistent with normal skeletal turnover. A periosteum and an endosteum develop as part of this cycle. Although the graft cortex never grows as thick as a normal jaw cortex, the graft itself retains a dense cancellous trabecular pattern that is favorable for dental implant placement because its density promotes osseointegration. It can also be favorable for supporting conventional dentures because the dense trabecular bone can easily adapt to a variety of functional stresses. Radiographically, the graft takes on the morphology and cortical outlines of the mandible or maxilla over a period of several years. Preprosthetic procedures, such as soft tissue grafts, can be performed at 4 months, when a functional periosteum has formed. Dental implants can also be placed at this point when treatment is phased.

Osseointegration of Dental Implants

The healing and remodeling of tissues around an implant involves a complex array of events. In this case, osseointegration refers to direct bone anchorage to the implant body, which can provide a foundation to support a prosthesis and can transmit occlusal forces directly to the bone (Fig 1-25). This concept was developed and the term coined by Per-Ingvar Brånemark, a professor at the Institute for Applied Biotechnology at the University of Göteborg in Sweden and the inventor of the well-known Brånemark implant system. During animal studies of microcirculation in bone repair during the 1950s, Brånemark fortuitously discovered a strong bond between bone and titanium. Today, we know that a fully anchored prosthesis can provide patients with restored masticatory functions that approximate natural dentition.

Fig 1-25 Unlike a natural tooth, which (unless ankylosed) is separated from the bone by periodontal ligament space and Sharpey fibers, the implant surface directly contacts the bone, with only a small interpositional layer (similar to a cement line on newly laid or existing remodeled bone).

Several key factors influence successful implant osseointegration, including the characteristics of the implant material (some appear to chemically bond to bone better than others) and maintenance of implant sterility prior to placement; implant design, shape, and macro-/microsurface topography (Fig 1-26a); prevention of excessive heat generation during bone drilling (Fig 1-26b); and placement within bone that has adequate trabecular density, ridge height and width, and systemic health (particularly good vascularity). When the recipient bone or graft is deficient in height, the portion of the implant prosthesis that is above the bone is greater than the length of the implant within it, possibly creating a destructive lever arm associated with bone resorption that will “loosen” the implant over time. A ridge that is too narrow (less than 5 mm to accommodate standard 3.75-mm-diameter implants) will leave some of the implant placed outside the bone or will force the surgeon to use less desirable small-diameter implants to gain the necessary osseointegrated surface area. Likewise, low-density trabecular bone frequently will either fail to osseointegrate or lose its osseointegration over time.29,30 Ideally, the marginal and apical parts of the implant should be fully engaged in cortical bone or in cancellous bone that has a high proportion of bony trabecular support. The ingrowth of fibrous tissue between the bone and implant also lowers the prospects for long-term success and the capacity to withstand mechanical and microbial threats. In some cases, these threats can be reduced by protecting against micromobility and by protective barrier membranes used during healing. It is crucial to achieve initial stability for successful osseointegration, as a clinically mobile implant has rarely been observed to osseointegrate.31 Once stability is lost, the implant can only be removed.

Fig 1-26(a) Placement of an implant traumatizes bone, stimulating a response to repair and remodel. The use of sharp burs and good saline irrigation minimizes trauma to both bone and soft tissues and helps maintain tissue viability. (b) The rough surface of the dental implant allows for fibrin attachment and subsequent production of adhesion molecules and cellular proliferation to enhance collagen synthesis and regulate bone metabolism.

Two critical measures of implant survivability are bone-to-implant contact (BIC) and implant stability quotient (ISQ). BIC is a microscopic measurement of the amount of surface contact between the implant and the bone. ISQ is a scale measurement (1–100) of implant stability, ranging from high (greater than 70) to medium (60–70) to low (less than 60). Clinically, most implants have an ISQ between 50 and 80, with higher ranges found mostly in the mandible. Regarding implant stability, BIC and ISQ measurements often diverge based on bone type. For example, in dense bone, initial stability could be relatively high (for example, greater than 75 ISQ), but such stability does not necessarily mean there is high BIC. Additionally, even if the implant’s BIC increases (via osseointegration) over time, the ISQ can remain unchanged. Conversely, in low- or medium-density bone, initial stability could be relatively low (say, between 55 and 60 ISQ), but the BIC could be relatively high. As BIC increases via osseointegration, the ISQ can rise correspondingly.

The healing process around an implant is the same as that in normal primary bone. Titanium dental implants cycle through a three-stage healing process consisting of an osteophytic phase, osteoconductive phase, and osteoadaptive phase.18 The osteophytic phase commences when a rough-surface implant is placed into the cancellous marrow space of the mandible or maxilla (Fig 1-27a). Blood is initially present between the implant and bone, and a clot subsequently forms. Only a small amount of bone is in contact with the implant surface; the remainder is exposed to extracellular fluid and blood cells. During the initial implant-host interaction, numerous cytokines are released to perform a variety of functions, from regulating adhesion molecule production and altering cellular proliferation to enhancing collagen synthesis and regulating bone metabolism. These events coincide with the start of the generalized inflammatory response to the surgical intrusion. By the end of the first week, inflammatory cells are responding to foreign antigens introduced by the surgical procedure.

Fig 1-27(a) Osteophytic phase: blood clot formation, infiltration of inflammatory cells, neovascularization by day 3. Ossification begins during the first week, and this phase lasts about 1 month. (b) Osteoconductive phase: woven bone foot plate and lamellar bone formation. This phase lasts for 4 months. (c) Osteoadaptive phase: balanced remodeling. The foot plate/woven bone thickens in response to the load transmitted through the implant. Some reorientation of vascular pattern may be seen.

While the inflammatory phase is still active, vascular ingrowth from the surrounding vital tissues begins by about day 3, developing into a more mature vascular network during the first 3 weeks following implant placement. In addition, cellular differentiation, proliferation, and activation begin. Ossification also begins during the first week, and the initial response observed is the migration of osteoblasts from the endosteal surface of the trabecular bone and the inner surface of the buccal and lingual cortex to the implant surface. This migration is likely a response to the release of BMPs during implant placement and the initial resorption of bone crushed against the metal surface. The osteophytic phase lasts about 1 month.

The osteoconductive phase is initiated once the bone cells reach the implant and spread along the metal surface via osteoconduction, laying down osteoid (Fig 1-27b). Initially, this is an immature connective tissue matrix, and the bone being deposited is a thin layer of woven bone called a foot plate (basis stapedis). The fibrocartilaginous callus is eventually remodeled into bone callus (woven and, later, lamellar) in a process similar to endochondral ossification. This process occurs during the next 3 months (peaking between weeks 3 and 4) as more bone is added to the total surface area of the implant. The maximum surface area is covered by bone 4 months after implant placement. By this point, a relatively steady state has been reached and no further bone is deposited on the implant surface.

The final or osteoadaptive phase begins approximately 4 months after implant placement (Fig 1-27c). A balanced remodeling sequence has begun and continues even after the implants are exposed and loaded. Once loaded, the implants generally do not gain or lose bone contact, but the foot plates thicken in response to the load transmitted through the implant to the surrounding bone, and some reorientation of the vascular pattern may be detected.

To harness the benefits of growth and differentiation factors at dental implant sites, one strategy is to apply autologous blood concentrates (ABCs) to alveolar ridge bone grafts. ABCs are growth factors produced from concentrated autologous blood platelets to promote wound healing (Fig 1-28). For example, in bone grafting procedures, platelet-rich plasma (PRP) has been shown to reduce the healing period for bone maturation, improve graft handling, and accelerate soft tissue healing.32 Platelets are a rich source of growth factors, including PDGF, TGF-β1, and TGF-β2.

Fig 1-28 Classic wound healing cascade.

Growth factors perform a wide range of functions (Fig 1-29). PDGF is considered one of the principal healing hormones in any wound. It initiates healing of connective tissue, including bone regeneration and repair. PDGF is a potent mitogen, angiogen, and upregulator of other growth factors. Mitogens trigger an increased number of healing cells, while angiogens generate new capillaries. Upregulation of other growth factors promotes fibroblastic and osteoblastic functions, cellular differentiation, and accelerated effects on other cells, such as macrophages. There is also evidence that PDGF increases the rate of stem cell proliferation.31

Fig 1-29 Growth factors perform a wide range of functions. PDGF is considered one of the principal healing hormones in any wound. It initiates healing of connective tissue, including bone regeneration and repair. TGF-β1 and TGF-β2 are involved in general tissue repair and bone regeneration. These growth factors also enhance bone formation by increasing the rate of stem cell proliferation, and they inhibit some degree of osteoclast formation and thus bone resorption. The fibrin component of PRP helps to bind the graft material and assists in osteoconduction throughout the graft by acting as a scaffold to support the growth of new bone.

TGF-β1 and TGF-β2 are involved in general tissue repair and bone regeneration. Their most important role appears to be chemotaxis and mitogenesis of osteoblast precursors and the ability to stimulate deposition of collagen matrix for wound healing and bone formation. These growth factors also enhance bone formation by increasing the rate of stem cell proliferation, and they inhibit some degree of osteoclast formation and thus bone resorption.

The fibrin component of PRP helps to bind the graft material and assists in osteoconduction throughout the graft by acting as a scaffold to support the growth of new bone. In addition, PRP modulates and upregulates the function of one growth factor in the presence of other growth factors. This feature differentiates PRP growth factors from other growth factors, which are single growth factors that only function within a single regeneration pathway.

Research that focuses specifically on the usefulness of ABCs for bone grafts related to implants remains cutting edge. The results of the first clinical study in humans appear promising and are in agreement with preclinical studies in animals. Results showed enhanced bone regeneration when PDGF, TGF-β, or other growth factors were applied.32 Several orthopedic studies also have shown evidence of the benefits of autologous fibrin that contained PDGF and TGF-β.33

Studies have shown that the cancellous marrow cells in graft material carry receptors for these growth factors.34 It also has been shown radiographically that adding platelet concentrates to graft material can significantly reduce the time to graft consolidation and maturation and improve the density of trabecular bone35 (Fig 1-30). The platelets degranulate within 3 to 5 days, yet their growth factors remain active for another 2 to 5 days. The platelet concentrates appear to give the process of bone regeneration a “jump start” on the cascade of regenerative events that ultimately form a mature graft.

Fig 1-30(a) The biochemical environment of an autogenous bone graft. (b) As early as 3 days after graft placement, significant cell divisions and penetration of capillary buds into the graft can be seen. (c) By 17 to 20 days, complete capillary penetration and profusion of the graft has taken place, and osteoid production has been initiated. (Reprinted with permission from Marx RE, Garg A. Dental and Craniofacial Applications of Platelet-Rich Plasma. Chicago: Quintessence, 2005.)

Adding growth factors to bone graft material may also increase the amount of bone that forms in the initial phase of osseointegration. In laboratory studies and some early human trials involving graft enhancement, BMPs(particularly recombinant DNA-produced BMP), TGF-β, PDGF, and IGF have shown promise in their ability to increase the speed and quantity of bone regeneration.36 Clinical studies evaluating the addition of PRP or platelet-rich fibrin (PRF) to graft material have demonstrated their ability to induce early consolidation and graft mineralization in half the time with a 15% to 30% improvement in trabecular bone density.10,37–41

It has been theorized that the enhanced presence of PDGF initiates osteocompetent cell activity to a greater extent than occurs in the graft and clot setting alone. The enhanced fibrin network created by PRP/PRF may also enhance osteoconduction throughout the graft, supporting consolidation.

Because of its ease of preparation and low cost, PRP has become an increasingly popular source of growth factors for many other types of surgery in addition to oral bone regenerative procedures. PRP is prepared in an outpatient clinical setting (Fig 1-31). The process involves extraction of a small amount of a patient’s own blood, which is then centrifuged to sequester and concentrate the platelets, and is completed in 20 to 30 minutes. PRP can be used to form a growth factor–rich membrane or to enhance a traditional membrane barrier. Because of its fibrinogen component, a gel form of PRP is also an excellent hemostatic tool, tissue sealant, wound stabilizer, and graft condenser, which allows for sculpting and excellent adherence in defects. Researchers have shown radiographically that adding PRP to graft material significantly accelerates the rate of bone formation and improves trabecular bone density as compared to sites treated with autogenous graft material alone.42,43 PRP also significantly enhances soft tissue healing; reduces bleeding, edema, and scarring; and decreases a patient’s self-reported pain levels postoperatively.44–47 Some evidence even suggests that adding PRP to graft material leads to bone growth that is more dense than native bone, a potential benefit that has not been reported in studies in which BMPs or growth factors were applied singularly.48 PRP growth factors are particularly attractive for cases in which conditions typically reduce the success of bone grafts and osseointegration49 (Fig 1-32).

Fig 1-31 Some evidence suggests that adding PRP to graft material leads to bone growth that is more dense than native bone. PRP growth factors are particularly attractive for cases in which conditions typically reduce the success of bone grafts and osseointegration.

Fig 1-32 Rehabilitation of a patient with a severely resorbed mandible using autogenous bone graft combined with PRP to obtain 15 mm of new bone. (a) The resorbed mandible represents the remnant of the inferior border, which is dense cortical bone. Note that the mandibular canal was unroofed by the resorption process so that the mental nerve now emerges in the second molar region. (b) The severely resorbed mandible represents a significant and yet often underappreciated loss of vertical bone height and loss of vertical dimension. (c) Reconstruction of the severely resorbed mandible is approached through a transcutaneous curvilinear incision in the submental triangle. (d) The periosteum is reflected from the labial and crestal areas bilaterally to the retromolar areas. In this 4-mm mandible, the mental nerves emerge from the resorbed crestal bone, and the hypertrophied genial tubercles are noted in the midline. (e) The first dental implant is placed 5 mm anterior to the emergence of the mental nerve, and each succeeding implant is placed parallel to and 1 cm apart from center to center. (f) Autogenous cancellous bone and marrow is then placed around all of the dental implants and compacted with bone packers to the height of the implant cover screws. (g) Once the liquid PRP covering gel is in situ, the consistency that it provides allows contouring and sculpting of the graft into a ridge form around the implants. (h) The implants seen at 4 months postsurgery through an intraoral crestal incision and now ready for the prosthetic phase. Note the excess bone growth even up to, above, and over the cover screw. (i) Severely resorbed mandible that has been grafted according to the tent-pole procedure, 1 week after surgery. Note the placement of the implants into the inferior border and the absence of mineralization, as one would expect in an autogenous cancellous marrow graft at this time. (j) Pretreatment profile of patient with inadequate mandibular bone height. Note the loss of facial vertical dimension and the pointed chin appearance often referred to as a “witch’s chin.” (k) Six months after graft placement and 3 months after loading the dental implants with a prosthesis, the mineralization of the graft is more apparent, and 15 mm of bone height has been gained. Note the development of a new foramen and mandibular canal in the bone graft. (l) Correction of facial vertical dimension and a normalized nose-to-chin relationship and contour as a result of the tent-pole grafting procedure. (Reprinted with permission from Marx RE, Garg A. Dental and Craniofacial Applications of Platelet-Rich Plasma. Chicago: Quintessence, 2005.)

In a controlled trial of patients undergoing bone augmentation for resected mandibles, investigators radiographically assessed the sites that were treated with graft material plus PRP and the control sites that were treated with graft material only. At 2, 4, and 6 months, the grafts containing the PRP were consistently rated as having reached maturity levels of nearly twice their actual levels. Histomorphometric assessment also revealed that bone graft densities in the PRP-treated group were 15% to 30% higher than those in the control group at 6 months.50

A 2015 study attempted to determine whether bone quality was enhanced before implant placement in extraction sockets treated with mineralized freeze-dried bone allograft (FDBA) alone or when combined with growth factors. One of the four randomized groups in the study received FDBA/beta-tricalcium phosphate (β-TCP)/PRP/collagen plug, and another group received FDBA/β-TCP/recombinant human PDGF-BB/collagen plug. The study concluded that PRP and rhPDGF-BB enhanced bone quality (removing D4 bone quality in the sockets) and that using PRP or rhPDGF-BB could facilitate the healing of extraction sockets while also decreasing the healing time.51

Conclusion

A general overview of the essential characteristics of human bone provides contextual understanding for dental clinicians who wish to specialize in dental implantology practice. This chapter explained how bone biology and physiology are crucial elements of specific clinical practices associated generally with dental and maxillofacial protocols and particularly with dental implantology. Of special importance, the dental implantologist should possess a thorough understanding of the differences between native and grafted bone with respect to implant placement, how the metrics BIC and ISQ provide insight into osseointegration and implant survival rates, and why PRP has become a popular clinical source of growth factors for several types of surgery, including oral bone regenerative procedures and dental implants.

References

1. Boskey AL, Coleman R. Aging and bone. J Dent Res 2010;89:1333–1348.