Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

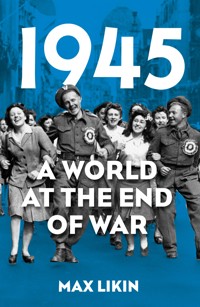

1945 is a fresh look at the final year of the Second World War. Evoking the disorienting strangeness of the end and aftermath of war, it narrates the lives of fifty protagonists caught in the ruins of warfare. From world leaders, artists, writers and musicians to housewives, servicemen and -women, concentration camp victims and children, Max Likin traces their stories through a momentous twelve months. Fast-moving and dynamic, 1945 is a powerfully evocative and often surprising narrative, showing how chance and fortune impacted different people at different times. This is a must-read for anyone with an interest in history or military history, and will astonish many with its fascinating juxtapositions of places and people.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 296

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

To Nancy, Adele, and Leah

Cover image: 1945 VE Day revellers in Fleet Street, London. (Chronicle / Alamy Stock Photo)

First published 2025

The History Press

97 St George’s Place, Cheltenham,

Gloucestershire, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© Max Likin, 2025

The right of Max Likin to be identified as the Authorof this work has been asserted in accordance with theCopyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprintedor reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic,mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented,including photocopying and recording, or in any informationstorage or retrieval system, without the permission in writingfrom the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 80399 916 6

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ Books Limited, Padstow, Cornwall

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

Contents

Introduction

January

February

March

April

May

June

July

August

September

October

November

December

Endings and New Beginnings

Notes

Bibliography

Acknowledgments

Introduction

The year 1945 marked the end of the Second World War. This cataclysmic event had no equivalent in human history. It spanned three continents, saw more men and women under arms, and caused more death and destruction than any other war. The unconditional surrender of Germany and Japan allowed no ambiguity. All vanquished nations had their homelands ravaged and political systems destroyed. Obliteration, not just capitulation, was the fate of Axis powers.

As much as we think of 1945 as the end, it was also a year of significant beginnings. In retrospect, 1945 announced important progress in nuclear medical science. It created international institutions to manage peace and stop wars of aggression, such as the United Nations and the Nuremberg Principles, to punish crimes against humanity. That same year quickened decolonization in Asia and Africa and it sparked important cultural shifts for women across many parts of the globe.

Conveying the conduct and experience of this pivotal year in a compact book is a challenge. Overarching themes and broad topics compete with minor facts for posthumous attention. Because wars are won on the battlefield, it is only natural that military campaigns and battles receive extensive notice, paying rightful tribute to human courage and sacrifice. Yet it is also sometimes useful to bring into focus far-flung elements and incongruous incidents that reflect the daily experiences of less-visible supporting characters.

I was walking through rows of stacks in a research library when my curiosity prompted me to pick up a war memoir from an American soldier by the name of J. Ted Hartman. Leafing through the book, it was hard to stop reading. Here was a young tank driver caught in the Battle of the Bulge on his first day of combat. Obeying strict orders, he was trying to do his best and live another day. This type of ‘in the moment’ history led me to other memoirs and biographies. They gave me the desire to retrace ‘lived experience’, not merely rational thoughts, but also primary emotions, widely shared innate feelings (joy, fear, sadness, anger, surprise, disgust). Rather than focus strictly on men and military doings, ideas on art, gender, and culture ought to be included. This is how larger-than-life personalities, such as Eleanor Roosevelt in the United States, Frida Kahlo in Mexico, and Svetlana Alliluyeva (Stalin’s daughter) in the USSR, came to gain prominence in this narrative.

Sketching idiosyncratic moments up to Victory in Europe Day on 8 May, in Russia on 9 May, and in Asia on 15 August, we can see that the conflict did not end on those momentous dates. The Allies still had to find a way to punish the perpetrators and their accomplices. As wartime propaganda offices were closed in September 1945, inchoate feelings of trauma and collapse surfaced simultaneously in triumphant and defeated nations.

The nineteenth-century Russian writer Leo Tolstoy in War and Peace famously asserted that victories owed much to lowly, invisible characters (such as muzhiks or peasants) doing the right thing at the right moment. By contrast, Scottish philosopher and historian Thomas Carlyle, true to his ‘Great Man’ theory of history, proposed that exceptional leaders, heroes, and geniuses drove historical change. The truth is more muddled. Ordinary individuals do heroic things and, conversely, mythical figureheads behave in ordinary ways. History is always open-ended.

The year 1945 came during a period when many of the great innovations in the industrial era came into widespread prominence: the telephone, railways, nuclear science, the combustion engine, chemical engineering, aircraft production, sea power, advertising campaigns, and moving images. Yet these technologies were deployed not only to secure victory but also to dehumanize, indoctrinate, and annihilate on an unprecedented scale. In essence, total war makes industrial killing possible. The most terrifying and haunting instance of industrial killing in this century remains the Nazis’ attempted genocide of the Jews. The Holocaust is not merely a past event but a historical burden; one that continually deepens the shadows of human progress.

More than that, the war gave rise to new means of pursuing domination, from computer-driven signals intelligence and multifaceted covert operations to the nuclear arms race, which ushered in a much more complex and intricate era of global history. From 1945 on, a proper, considered and shared moral appraisal of our universal ties would be the key to respecting human dignity and preserving the peace everywhere.

January

On New Year’s Day, the ice groans and shrieks under the tracks of J. Ted Hartman’s tank in the Battle of the Ardennes. That same day, Adolf Hitler bestows the highest military medal to the most fanatical Stuka bomber pilot the world has ever seen. As they shake hands, the ace pilot starts to protest.

In what remains of Budapest, diplomat Raul Wallenberg slips on the ice in front of the Swedish hospital. Not far from the Alsatian border, a combat surgeon questions the value and veracity of anatomy drawings. In Buchenwald, a blind French Resistance fighter is locked up with ‘the crazies’, crawling like worms across the concrete floor.

Accompanied by his daughter, Sarah, Winston Churchill lands in Malta trying to catch his breath before the ‘Big Three’ Yalta Conference.

Red Army signals operators have no words to describe liberated Auschwitz.

In Mexico City, the weather is delightful. Frida Kahlo sits at her easel painting a bouquet of creamy magnolias. Light-hearted swing jazz music fills the courtyard. Svetlana Alliluyeva, Stalin’s daughter, is three months pregnant and she has just moved into the lavish House on the Embankment.

In Kunming, underground Viet Minh soldiers sitting at the Café Indochine are waiting for OSS operatives to show up.

Big guns boom in the bitterly cold Battle of the Ardennes. On New Year’s Day, US tank driver J. Ted Hartman is ordered to attack the village of Chenogne, located south of Bastogne. Trees are blanketed in thick snow and houses are pockmarked with craters, leaving a clearing for German Panzerfaust bazookas. The ice-coated roads moan under the tracks.

A fortnight earlier, in the predawn darkness and fog of 16 December 1944, the Germans caught the Allies by surprise. They had secretly marshaled 410,000 men and kept radio silence, thereby eluding the vigilance of the Ultra codebreakers. Hitler’s personal gamble is to cut the Allies’ logistical lines of communication by taking the transportation centers of Liège and Antwerp, to bring the Western leaders to the bargaining table. The attacking German force of twenty-four divisions extends some 50 miles deep and 70 miles wide.

Situation 12 hours, 27 December 1944, Battle of the Bulge. (NARA NAID: 16681813 Maps and Charts)

As a simple conscript, J. Ted Hartman wants to be a good soldier. He enlisted in the Army Reserves at a recruiting station in Des Moines, Iowa, in May 1943, right out of high school. After six months of training, he was declared fit for service overseas in Europe. His point of embarkation on the East Coast was Camp Kilmer, New Jersey. At the pier, Red Cross girls gave donuts and coffee, and an army band played popular tunes.

On the night of 19 December, Hartman sailed from England to Cherbourg Harbor. At Soissons, he learned that his unit had become part of the US Third Army, under the command of General George S. Patton – wear a tie at all times and a helmet outside the tank.

At around eight o’clock on Christmas night, Hartman’s tank left Soissons on a 90-mile blackout march. A French woman invited the Americans in for some hot chocolate. She refused payment but said, ‘Merci’, when offered cigarettes.

Frost has formed over the interior of the thick steel walls and Hartman tries to keep his feet dry to avoid frostbite. He has cut a wool army blanket into strips 3in wide, and he changes the wrappings every few hours. On this day, his second day of action, he sees his first dead American soldier lying near his tank and wonders how humans can stand the sight.

By the end of New Year’s Day 1945, the Americans are able to hold on to the village of Chenogne, which by now has lost twenty-nine of its thirty-one homes and the church. Late the next day, unexpected mortar fire explodes and Hartman sees one of his friends lifted off the ground in a standing position and fall dead on his back.

US infantrymen move along a road through Beffe, Belgium. (NARA NAID: 12010150 RG 111)

M-4 Sherman tanks lined up in a snow-covered field near St Vith, Belgium. (NARA NAID: 16730735 RG 111)

American soldiers of the 289th Infantry on their way to cut off the St Vith–Houffalize road in Belgium. (NARA NAID: 531244 RG 111)

It’s a fairly long drive through dark patches of pine woods. Stuka pilot Hans-Ulrich Rudel is driven past several guard posts. With close to 2,000 successful missions, Rudel is by far the best Luftwaffe pilot of all time. Wing Commander von Bülow welcomes him at the Führer’s Western HQ and offers him a cup of coffee, during which the two discuss the Eastern Front.

To be on the ground is a complete waste of time, in Rudel’s opinion. When landing his Stuka airplane at an airfield, his only wish is to discuss the next target for the day with other pilots and listen to a flight sergeant reporting that the airplane is refueled, repaired, and ready to go. After some desultory small talk about the situation in Hungary, Rudel follows von Bülow through several rooms and suddenly is face to face with the commanders. His mind draws a blank when he sees Hitler, except for the thought that he should have changed his shirt.

The top brass is grouped around a long table studying an oversized map. Reichsmarschall Göring is beaming. Admiral Dönitz, Field Marshal Keitel, and Colonel General Jodl scrutinize Rudel with intense curiosity. The Luftwaffe pilot should long ago have fallen from the sky, disappearing somewhere over the Eastern Front.

A corpulent Göring wedges himself forward in line with his rank of Reichsmarschall. He has a bloodthirsty grin on his face. He is a former ace fighter pilot, the recipient of the coveted Pour le Mérite, known as the ‘Blue Max’. Right after Dunkerque, he promised Hitler that the Luftwaffe would win the war from the air and rain down fire on Britain. However, his lifelong opium addiction got much worse, and he now often dresses up in a Roman toga at his country residence at Karinhall. Built in the manner of a hunting lodge, his retreat is filled with priceless, plundered art from national museums in occupied Europe. Der Eisener Sammler has a weakness for masterworks depicting female nudes in mythical settings. He possesses one of the two largest art collections in the Third Reich.

The Führer offers his hand to Rudel. In recognition of his last operation, he is awarding him the very highest decoration for bravery: the Gold Oak Leaves with Swords and Diamonds. Ace flyer Rudel is promoted to the rank of group captain. In his left hand Hitler holds a black velvet-lined case. The lights in the room make the diamonds sparkle in a blaze of prismatic colors. ‘Now, you have done enough flying. Your life must be preserved for the sake of our German youth and your experience.’

Rudel loudly clicks his heels, ‘My Führer, I cannot accept the decoration and promotion if I am not allowed to go on flying with my wings.’

No one ever contradicts Adolf Hitler. The smile vanishes from Göring’s face. The generals freeze, wondering what will happen next. The Führer looks at the ace flyer gravely, then his expression changes, ‘All right, you may go on flying.’ Everyone offers congratulations. We need more soldiers like him.

On 13 January, Russian boots kick open the trap door in the Benczúr Street cellar. Raul Wallenberg shows his Swedish diplomatic papers, saying he must reach the highest Soviet authorities. There is now a glimmer of hope that Jewish families will no longer be rounded up. The Russians want to know why he is still in rubble-filled Pest when all the diplomats stayed in Buda. This goes on for an hour. In deserted apartments nearby, axes are hacking open parquet floors and smashing up antique furniture to collect firewood and live another day.

Raoul Wallenberg. (Pressenbild, Wikimedia Commons)

The Swedish diplomat’s Russian is actually rather good. Belonging to a distinguished Swedish family of bankers and industrialists, Wallenberg studied Russian in high school and then architecture at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor. As First Secretary of the Swedish Embassy in Budapest, he lost no time in designing a Swedish ‘protective passport’. Printed in blue and yellow and bearing the Three Crowns heraldry in the center, these official-looking documents spark tears of gratitude when they change hands. With the help of hundreds of volunteers, the Legation saved between 30,000 and 100,000 people from certain death. Some 700 Jews are now squatting on the premises of the Legation.

One day, Wallenberg will appear on commemorative stamps and street names, on scholarships, on study halls and in ritual academic debates. To be sure, war is the defeat of diplomacy. There is no room here to analyze the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), whose leaders for a long time thought the Third Reich had won the war. Thus, they did not protest when trains packed with mothers and children were headed east to some unknown destination. Red Cross women in various capitals sent alarmist telegrams to the ICRC, demanding to know the cattle cars’ final destinations. At one moment or another, Wallenberg was creating such a stir that the ICRC felt compelled to act. By that time, however, 1 million children had been murdered.

Wallenberg is driven in his blue Studebaker to the Russian headquarters on Erzébet Királnö (Queen Elizabeth), where he spends the night. The next day, he makes a brief appearance at the Swedish Legation, where he doles out money to his Hungarian assistants. He slips on the ice in front of the Swedish hospital. The hospital manager helps him up and walks him to his car. ‘I’ll be back from Debrecen in a week.’ The Studebaker disappears on the road east, flanked by a Soviet motorcycle escort with sidecars.

At the end of converging lines of hedges and fences, in the snowy village of Herrlisheim, across from an Alsatian inn, men of a US Infantry medical section lean against an ambulance that is well stocked with champagne bottles. They pass a bottle of schnapps, puffing their cigarettes. ‘Geez, that’s a sin,’ says one, wiping his mouth.

‘A mortal sin,’ says another gravely. ‘Fucked this broad right in the snowbank. Right in the goddamn snowbank. How do you like that?’

The combat surgeon enjoys and records these exchanges in his diary, but a part of him doubts the value of words. When blood comes spurting through a mass of torn clothes, muscles, bones, and subcutaneous tissues ripped away, forming a twisted, matted jungle, the word anatomy might seem incongruous.

Near dawn, after deafening firing with a rush of their artillery coming in overhead, as men keep materializing out of fog, white with snow, exhausted and matted with blood, he sees a wounded, profoundly happy shadow approaching the tent, whooping like a drunk in a Western saloon, flesh ripped from his thigh. The medics push him gently down to cut clothing away. He waves his M-1 rifle around. He won’t let it go. Two years he carried that fucker around and cleaned it and drilled with it and marched with it, and today he got the Kraut right in the ring-sights and he squeezed down, and he killed the son of a bitch.

In the aid station, so many of them want to return to the front to be with their friends. Simultaneously, the wounded soldiers witness some token of humanity. They see that the medics want to keep them from harm, and they open up. Some soldiers are whimpering remnants on litters, terrified into a fetal position, incapable of anything except convulsive shivering.

Medics sponge with an aid packet, while a helper gently loosens the tourniquet to let the bleeding start just enough for recognition. The high-pressure arteries spurt first but they can hardly ever be located. The task then is to put in a suture and hope for occlusion. Hopefully the dressings will be enough to staunch small veins and capillaries.

Working without gloves and with no time to boil instruments, Brendan Phibbs somehow does pretty well with instruments carried in jars of sterilizing solutions. They work as a team. He ties sutures using two hemostats, while a helper holds a third. It’s efficient. The surgeon has learned to inject a local anesthetic quickly, all through the wound. His irritability is a different matter when supplies of novocaine are down.

‘Mind you, fifty bloody Tiger tanks tomorrow at dawn.’ The supply officer has been arguing with the artillery commander and it looks like, this side of Paris, the artillery has just fifty rounds of ammunition.

A kind of delirium, a paralyzing fear insinuates itself among the soldiers. The terror is palpable. Twenty minutes of ammunition. You know that something is seriously wrong when you observe cooks in the mess truck, pots and pans flying, looking for a bazooka.

Fresh-falling, quieting snow. Shapes of glum men and guns. Muffled sounds, and that implacable logic. The men keep staring at each other. ‘It’s the fuckin’ rear echelon, those bastards with their eight-hour days and their French whores and their black market …’ A sergeant pounds his fists against the wall. ‘Them fuckheads, them fuckheads, them cowardly lazy fuckheads! After all we’ve done, after all we’ve been through, after the way we beat those goddam Krauts!’

At the command post the new colonel is taking charge. They call him ‘Charlie’ or ‘West Man’. He saved them all earlier, opposing an untimely suicide attack, defiantly hindering strict orders. Waiting for dawn, Phibbs recalls friends at home, safely crossing Grand Central, making their way to suburban homes. Children are asleep, teddy bears and dolls and games on the living-room floor.

As explosions rock the command post in the basement, ‘Charlie’ shouts orders. Those observing him are convinced the radios can’t possibly function. ‘Stop this goddam panic!’ Amid frantic sounds and shell bursts, people are doubled over. Phibbs’ kneecaps begin to twitch uncontrollably. The colonel slams the phone down, ‘We’re not retreating anywhere.’

Buchenwald is a concentration camp situated near Weimar in central Germany. The camp opened in 1937 and, by now, almost 240,000 prisoners have been sent there. In early January, effective immediately, the Nazi authorities have decided to halve food rations to finish off all prisoners.

At the very bottom of a strict prison hierarchy are those known as Muselmänner, who have but a few days to live. Among those who are past caring, we find a pint-sized, blind French Resistance fighter. Arrested in Paris, he survived thirty brutal interrogation sessions. One of his five interrogators tossed him against the wall. At the end of each day, with a guiding hand in the back of his neck, Jacques was pushed down corridors and stairs, shoved into a van and driven back to prison. The next day, another interrogation session would begin. The Germans can’t quite fathom how a blind person could be a Resistance leader.

When the train pulled out of the station in Paris, the French prisoners sang a rousing ‘Marseillaise’. The weather was freezing. Upon arrival, as they tumbled out of the wagons, a fellow inmate broke his wrist intercepting a rifle butt that was meant to finish off the blind laggard. Now they have locked up Jacques with demented and paralyzed people, crawling upon each other like worms.

The first liberators arrive on horseback at midday on a snowy, but sunny Saturday. The Soviet troops discovered the Auschwitz camp almost by chance. The stench is beyond description, something like a monkey-house, more hallucination than reality. Inside the barbed wire, corpses are scattered everywhere, with unwieldy piles by the doors of the huts. There’s little obvious difference between the dead and the living – haggard survivors with faces like hunted beasts.

The Red Army soldiers point to the stars on their caps, ‘Germania Kaputt’ and ‘Russki! Russki’.

Huge eyes, ‘SS?’

‘Nix SS, Hitler Kaputt!’

The Russian soldiers say more help is coming, looking sideways, looking elsewhere. The Häftlinge have reached untouchable depths of degradation. ‘Kasha, Kasha!’ they shout, imitating someone putting food in their mouth. They have tears in their eyes but can’t even shed them.

‘Da’, perhaps three or four camps. The interference is frustrating. The signals operators look at one another. Majdanek times four? Ask them again.

Other units think the trouble can be subdued. More medical help, food, water, nurses, medical personnel. We need to requisition supplies from the surrounding villages and towns, and a liaison regiment to clear this up, and a film and photo unit. No, electricity’s down. No, start with aerial views of the factories. There’s no light inside the huts.

A Red Army colonel learns about the death camp from the commander of the 100th Division and makes his way to Auschwitz. What is he expected to do? This isn’t just one camp, but vast compounds behind high-voltage barbed wire. He peeks into barracks that have been sprayed by machine-gun fire. He notices pools of frozen, glass-like blood and piles of corpses inside. He discovers successive sites.

The crematoria were not abandoned by the SS but dynamited. One was still intact on 26 January, just before Soviet troops reached Auschwitz. The flames over there? That’s what’s left of the thirty barracks of ‘Canada II’. The warehouses of ‘Canada I’, here, were left alone. By the Bahnrampe, seven wagons are standing, full of male and female clothes, perhaps half a million pieces. His soldiers show him bags filled with hair and tell him there are 7 tons of hair – 7 tons?

Prisoners stumble behind him to act as witnesses. They mumble in fifty languages. There are mountains of suitcases, glasses, dental fixtures. Surrounded by other officers, the colonel now comes across eighty-odd children near an empty experiment room. The ache inside his head will never end. The Germans have taken the surgical tables with them and just about everything else, even tweezers.

The Red Army officer doesn’t know where to begin. Who is going to clean this mess up? Should he assist the children first? We need the Polish Red Cross. Now!

The wartime love letter discloses and bares. ‘My Darling,’ writes Clementine Churchill from 10 Downing Street, ‘I was much relieved to get the signal you had reached Malta safely, flying with the blizzard on your tail.’ She mentions the delectable little London house they visited together in Kensington. It’s a brief letter, which ends on a high note: ‘Seven inches of snow fell last night but it’s much less cold – the radio announced this morning that coal distribution by Army lorries begins to-day! It didn’t mention who thought of this.’

The prime minister has left London on 29 January 1945 in his luxurious, four-engine Skymaster, stopping in Malta on the first lap of his journey to Yalta. Traveling to ‘the Riviera of Hades’, as he calls it, Churchill finds solace in the presence of his daughter, Sarah. From Malta he sends Clementine a coded telegram for ‘Mrs. Kent from Colonel Kent’, ‘Quite well again but spend most time in bed in Orion’s comfortable cabin. Miss you very much. The world is in a frightful state.’

In truth, Churchill has had a high temperature for several hours and cannot be transferred from the aircraft to the cruiser, HMS Orion. His physician, Lord Moran, is lost for an explanation.

Churchill considers this the closing phase of his life. Black velvet, eternal sleep is near. He will be carried to a better world. ‘When it comes to dying, I shall not complain. I shall not meow.’

Although a careful planner with a keen eye for detail, Churchill is an inveterate optimist when it comes to risk and risk-taking. A long time ago, he had fired at Boers and they had captured the military train in which he was traveling, then he had escaped. During the First World War, he had surmounted the failure of the Dardanelles and, by a hair, avoided deadly artillery fire in the trenches. In Manhattan, he was struck by a car arriving from the right. He was taken to the Lennox Hill Hospital, where he developed pleurisy. Several times, engine trouble in an airplane had nearly ended his life. At the previous conference with Allied leaders in Teheran, he had struggled hard with pneumonia.

Looking out from HMS Orion’s deck into Valletta Harbor, the prime minister sees widespread destruction. Rusting hulks peek out of the water and twisted copper and zinc the color of oysters points to much aerial bombing. Not even the warm colors and brilliant sunshine can cheer him up. Churchill is aware that he needs to review vital maps, charts, and papers in Malta to prepare for the Big Three meeting in Yalta. However, an RAF York transport aircraft carrying staff members from the Foreign Office and War Cabinet has bypassed Malta in the fog and has been lost at sea along with the precious research papers. Churchill acutely feels the loss of life and vital documents.

Noticing the palette of warm colors slightly reminiscent of the Atlas Mountains, as he leans over the balustrade of HMS Orion Churchill cannot help but recount his implacable feud with Adolf Hitler. What would have happened if they had met in September 1932 in Munich? To trace the life of his forebear, John Churchill, 1st Duke of Marlborough, Churchill had crossed the Channel to see the scenes of past military victories. He had journeyed through Belgium and Holland and a friend of a friend had tried to introduce him to Hitler in the Bavarian capital. He had waited at his hotel, but Hitler never showed up, despite the pleas of the go-between. In any case, Hitler had asked, ‘What part does Churchill play? Isn’t he in the opposition, and no one pays attention to him, right?’ ‘And so are you’, the go-between had replied.

Next, he had wanted to continue his journey to Venice for a holiday but then had been taken ill with paratyphoid fever. Two weeks in a sanatorium in Salzburg.

In late September, Churchill had returned to England to proceed with Marlborough’s biography but then, walking in the grounds of Chartwell, he had collapsed. A recurrence of the paratyphoid. An ambulance had driven him to a nursing home in London. A severe hemorrhage from a paratyphoid ulcer. What if he had died that early fall and Hitler had been defeated the following year at the 1933 elections?

Churchill decides to write a long letter to Clementine, telling her he is looking forward to meeting Harry Hopkins that night. Towards the end of his letter, he expresses concern for German mothers: ‘I must confess to you that my heart is saddened by the talks of the masses of German women and children flying along the roads everywhere in forty-mile-long columns to the West before the advancing Armies.’ Churchill knows that there are 8 million ethnic Germans trapped in Russian territory:

Tender Love my darling

I miss you very much

I am lonely amid this throng

Your ever loving husband

W

Under heavy escort, USS Quincy is at long last expected to complete its 5,000-mile journey tomorrow. Tethered to their listening devices, the sonar men below deck were especially nervous, convinced the enemy knew of this presidential voyage. Heliograph messages kept warning of potential German U-boat gates.

A grand reception at Gibraltar. Surrounded by a phalanx of Secret Service men, including one exceptional swimmer, President Roosevelt retires early, sleeps late, and has breakfast with his daughter, Anna. In the evening, he watches a motion picture with aides and close friends.

The deep, steady roll of USS Quincy at times inflicts atrocious pain on the hips of President Roosevelt. Meanwhile, the Yalta research material and recommendations prepared by the State Department remain below deck. Lifting and falling easily in a head sea, Quincy begins a series of fast zig-zag maneuvers approaching the southern tip of the Iberian Peninsula.

Once inside the Mediterranean, Quincy makes radio contact with Tangier.

The mood on board noticeably lightens past the Strait of Gibraltar because of fewer U-boats in the Mediterranean. Lucky day. The mood is such that the staff spontaneously insist on another party for the president, because today – 30 January – is his birthday. In the small dining room, no fewer than four birthday cakes are presented to Roosevelt: one from his favorite Filipino chef, one from staff officers, another one from the warrant officers, and a fourth one from the crew, with an odd inscription engraved in icing. Is it the number ‘5’, for a fifth term, or an odd question mark in the shape of lazy inverted ‘S’ that provokes hilarity?

Roosevelt decides he needs fresh air in the company of Anna. The president’s wheelchair emerges along the gray silhouette of Quincy and sailors crowd the deck to gape and gawk. Anna instinctively looks for the gun mount that screens the wind, conscious of her father’s sinus flare-ups. The tender moment of togetherness is captured on film.

Mexico City is a bucolic haven of peace. Frida Kahlo sits at her easel, painting, taking a long look at a simple bouquet of magnolias, which she started a month earlier. The ivory-white flowers bloomed a fortnight earlier. Jacqueline Lambda held the splendid flower in front of her, slightly higher than her gaze, then she gave it to her daughter, Aube. The scent is dignified, overpowering. Frida Kahlo cannot take her eyes off her trompe l’oeil effect when she inserted an oversized cactus flower amid the creamy white petals. The short flight of female beauty and evanescent color harmony.

It’s the next day. Frida Kahlo wakes up in her bed and catches a glimpse of herself in the mirror encased above the bed, a gift from her father. She loved her father. ‘You don’t need feet when you have wings,’ he told her. She starts painting her face, her gift. Begin with sunshine.

She hears them distinctly just before dawn. Spider monkeys, hairless dogs, macaws, hens, an eagle, and a fawn. Sounds of chains rattling. The two parakeets are chirping, squawking. The animals are so loud across the patio of Casa Azul, and it’s so early. If the Nazis could arrest Frida, they would immediately do it. Degenerate art!

Svetlana Alliluyeva is three months pregnant and looking healthy. The father of the baby is Grigory Morozov, a student at the Moscow Institute of International Affairs. The two got married the previous year when she was 18. They just moved into the House on the Embankment, a block-wide apartment building on the banks of the Neva.

Svetlana Alliluyeva is vivacious, smart, and her English is excellent. She found out about her mother’s suicide, for instance, from foreign magazines. So, it wasn’t an ordinary death.

The pictures reveal her as the apple of her father’s eye. Aged 16, Svetlana met the irresistible, 38-year-old Aleksei Kapler, the most famous screenwriter in the USSR. She was young and his love of risk excited her. What was Kapler thinking when he invited her to dance? Her bodyguard started sweating profusely, but what could he do when this Jew from the Moscow intelligentsia approached her? Rush between them and reach for his gun?

Kapler loved what he called the freedom within her and her bold judgments. She thought him the cleverest, kindest, most intelligent person on earth. They watched Greta Garbo’s Queen Christina together and he bought her Hemingway’s banned For Whom the Bell Tolls. When she telephoned him from her grandmother’s apartment in the Kremlin, she called him ‘Lyusa’, and her grandmother thought she was talking to a girlfriend. But Stalin knew everything.

Kapler was a man of honor, perhaps that was the real scandal, and he could not be intimidated. He had written a cryptic article in Pravda about their relationship. Ostensibly a soldier’s description of Stalingrad, the piece was in effect a love letter to Svetlana: ‘My love, who knows whether this letter will reach you?’ He describes watching snow falling outside the Kremlin walls and asks if she remembers their rendezvous at the Tretyakov Gallery.

‘Your Kapler is a British spy!’ Stalin said. Turning to her nanny, he said, ‘Oh, she loves him …’ Then Stalin slapped Svetlana across the face for the first time in her life.

It wasn’t long before Kapler signed his confession. After a year in solitary confinement, he was deported to Vorkuta. Deep inside her, however, Svetlana knows that they will be reunited.

What would have happened if, late in 1944, a US reconnaissance pilot by the name of Lieutenant Rudolf Shaw had not met with engine trouble and decided to parachute to safety? Local Viet Minh units had been the first to reach him, while French patrols were sent to locate him. The Viet Minh did not speak a word of English, which was unnerving.

Wearing a threadbare and patched Kuomintang military uniform, with thin canvas shoes full of holes, Ho Chi Minh had introduced himself in colloquial English. It would later be said that this man had an extraordinary gift to immediately establish relationships with his interlocutors, whether they were ministers or peasants. Some have even called him a dangerous comedian.

Ho had next offered to accompany the American flyer back to the Kunming base in China. During the arduous trek by night, Ho Chi Minh had enquired about the possibility of obtaining a radio, as well as arms and medicine.

When instructing his comrades in arms, Ho frequently insisted on waiting for the right moment (tho co or co hoi), yet it was tough to keep up with the rapidly changing situation. The northern region was suffering from rampant famine. The Japanese refused to open state granaries or to allow rice shipments from the fertile Mekong Delta to the north. In the cities, rich bourgeois people were trading their jewelry, while peasants had started to eat roots, weeds, and even the bark of trees. On the ideological front, the French imperialist wolf is about to devour the Japanese fascist hyena.

Ho looks like a frail peasant with silver hair. In a world of political survivors, he is in a league of his own. When he left his country in 1911, together with a few hundred other young Vietnamese, little did he know that he would spend thirty years dodging security forces in half a dozen countries. In 1914, he had escaped to London, working as a dishwasher and assistant pastry hand in a hotel. Back in France, he had made an appearance at the Paris Peace Conference.