6,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Open Book Publishers

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

This book draws on the life stories told by shepherds, farmers, and their families in the Andalusian region in Spain to sketch out the landscapes, actions, and challenges of people who work in pastoralism. Their narratives highlight how local practices interact with regional and European communities and policies, and they help us see a broader role for extensive grazing practices and sustainability.

A Country of Shepherds is timely, reflecting the growing interest in ecological farming methods as well as the Spanish government’s recent work with UNESCO to recognise the seasonal movement of herd animals in the Iberian Peninsula as an Intangible Cultural Heritage.

Demonstrating the critical role of tradition, cultural geographies, and sustainability in the Mediterranean, this book will appeal to academicians but also to general readers who seek to understand, in very human terms, the impact of the world-wide environmental crisis we are now experiencing.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Ähnliche

A COUNTRY OF SHEPHERDS

A Country of Shepherds

Stories of a Changing Mediterranean Landscape

Kathleen Ann Myers

Translations by Grady C. Wray

https://www.openbookpublishers.com

©2024 Kathleen Ann Myers

This work is licensed under an Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International (CC BY-NC 4.0). This license allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the text; to adapt the text for non-commercial purposes of the text providing attribution is made to the authors (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work).

Attribution should include the following information:

Kathleen Ann Myers, A Country of Shepherds: Stories of a Changing Mediterranean Landscape, with translations by Grady C. Wray. Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers, 2024, https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0387

Copyright and permissions for the reuse of some of the images included in this publication differ from the above. This information is provided in the captions and in the list of illustrations. Every effort has been made to identify and contact copyright holders and any omission or error will be corrected if notification is made to the publisher.

Further details about Creative Commons licenses are available at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

All external links were active at the time of publication unless otherwise stated and have been archived via the Internet Archive Wayback Machine at https://archive.org/web

Digital material and resources associated with this volume are available at https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0387#resources

ISBN Paperback: 9 978-1-80511-206-8

ISBN Hardback: 978-1-80511-207-5

ISBN Digital (PDF): 978-1-80511-208-2

ISBN Digital ebook (EPUB): 978-1-80511-209-9

ISBN XML: 978-1-80511-210-5

ISBN HTML: 978-1-80511-211-2

DOI: 10.11647/OBP.0387

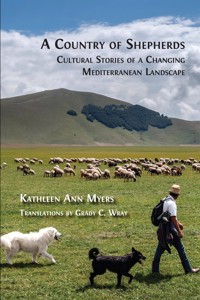

Cover image: photograph by Costagliola (purchased from Deposit Photos, ID: 266971314)

Cover design: Licia Weber and Jeevanjot Kaur Nagpal

For Mark and Anna

Table of Contents

About the Author

Preface

Acknowledgements

Translator’s Note

List of Illustrations

Introduction

Pastoralism in Spain

Pastoral Practices and Shepherds’ Narratives

Historical Practices and Cultural Narratives

Life Stories and Pastoralism: Method and Scope

New Pathways: Overview

Pastoralism: A Contextual Background and Terminology

Maps and Resources

1. New Directions in the Sierra Norte de Sevilla: Juan Vázquez Morán and Family

2. Teacher of Tradition: Pepe Millán and Family (Zahara de la Sierra, Parque Natural Sierra de Grazalema, Cádiz)

3. Transhumance, Diversification, and New Collaborations: Fortunato Guerrero Lara (Sierra de Cardeña y Montoro [Córdoba] and Sierra de Segura [Jaén])

4. Inheriting a Farm: Marta Moya Espinosa, Castillo de las Guardas (Seville)

5. New Initiatives within Tradition: Ernestine Lüdeke and the Dehesa San Francisco and the “Fundación Monte Mediterráneo” (Santa Olalla del Cala [Huelva])

6. The Scaffolding for the Future of Pastoralism: Collectives and Training

Conclusions: Challenges and Opportunities

Systemic Challenges

A Path Forward

Selected Bibliography

Index

About the Author

Kathleen Ann Myers is Professor of Spanish and History at Indiana University-Bloomington. She received her doctorate in Hispanic Studies from Brown University. Kathleen has published widely on a variety of topics, including books about women writers in colonial Mexico (Liverpool 1993, Indiana University Press 1999, Oxford 2003) and the Spanish conquest and colonization of the Americas (Texas University Press 2007). Her recent studies include books on cultural geographies and coloniality in contemporary Mexico (University of Arizona Press 2015, University of Toronto 2024).

This research has been generously funded by a variety of organizations, including Indiana University, the National Endowment for the Humanities, the Fulbright Scholar Program, the Spanish Ministry for Education and Culture, the Centro de Estudios de Ciencias Sociales (Mexico), the American Philosophical Association, the Huntington Library, and the Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas of Spain (CSIC).

Preface

For centuries, pastoralism has occupied a key place in cultural narratives about the Iberian Peninsula, and the traditional locales and travel ways of shepherding hold deep significance for the collective imagination of many Spaniards today. Drawing on a vast array of scholarship, popular culture, and interviews with shepherds and their advocates, A Country of Shepherds: Stories of a Changing Mediterranean Landscape suggests that shepherding, and pastoralism in general, is being reconfigured and even remarketed to a new generation. Such internationally renowned events as the annual Festival of Transhumance (established 1997), during which sheep are driven through the streets of downtown Madrid along ancient rights of way, and UNESCO’s proclamation of transhumance in Spain as Intangible Cultural Heritage (2023), are integral to this phenomenon. Emerging cultural geographies and narratives of pastoralism shape local, regional, national, and European economic and environmental initiatives as shepherds, bureaucrats, and the public frame their own roles in the development of new national and environmental projects. Indeed, more is at stake than simply cultural identity. Due to the growing threat of global warming, southern Spain in particular is at risk for increasing desertification if modern intensive agricultural practices cannot adapt.

Over the course of decades of traveling, working, and at times living in Spain, I watched this transformation in both the practice of and narrative about pastoralism, but by 2015 I wanted to understand it more deeply. As I started interviewing shepherds, I learned that the success (and even the survival) of these traditions also depends on the support of many governmental and grassroots initiatives and organizations, as well as the general public. As an outsider to this world of pastoralism, I share here both these interviews and my process of coming to understand our own roles in supporting these ancient but very relevant ways of managing ecosystems and cultural landscapes.

Based on a series of about sixty interviews I carried out, the six case studies at the core of A Country of Shepherds document the lives of a handful of shepherds, farmers, and families, along with their advocates, in Andalusia, Spain. Through them, we see the landscapes, life practices, and challenges of pastoralism (both transhumance and extensive grazing) as well as the vital significance of their work as a globally interconnected system. They give a face and voice to a complex national and international conversation about sustainability, food systems, and cultural traditions. By sharing this living archive of interviews and my own process of discovery along the way, A Country of Shepherds documents this ancient system and its transformation in the twenty-first century — and suggests ways we all, as global citizens, can help.

Acknowledgements

This project has been generously funded by the Spanish Ministry of Culture, Education, and Sports and Indiana University’s Presidential Arts and Humanities Program, the Office of the Vice-Provost for Research, and the College of Arts and Humanities Institute. I owe an enormous debt of gratitude to these institutions as well as to a host of individuals without whom this project would have been impossible. With patience, and often humor, people in Spain shared their knowledge and practices, gently guiding a curious but ignorant outsider in the hopes that their story might be told more widely to effect change. My deepest thanks go to my teachers on the ground and their families, who are the focus of five of my case studies: Juan Vázquez Morán, Pepe Millán, Fortunato Guerrero Lara, Marta Moya Espinosa, and Ernestine Lüdeke. They took time they barely had to share their practices and experience with me. In addition, many advocates for traditional grazing and sustainability provided valuable insight into the broader movements and organizations. My special thanks go to Jesús Garzón Heydt, María del Carmen García, Paco Casero, José Ramón Guzmán Alvarez, Ana Belén Robles Cruz, and Paco Ruiz. Yolanda Mena Guerrero is in a league of her own as she helped me interpret the results of my interviews and suggested ways to showcase pastoralism today.

Many friends and colleagues on my side of the charco (pond) further supported this project with encouragement, letters of recommendation, and even lodging over the years it unfolded. My sincere thanks to Consuelo López-Morillas, Cathy Larson, Rob and Karen Green-Stone, Charles Ganelin, Steven Wagschal, Manuel Díaz-Campos, Melissa Dinverno, and Alejandro Mejías-López. Five graduates of Indiana University worked with me as valuable cultural interpreters, researchers, transcribers, and translators for this volume; I have been extremely fortunate to have worked with each of them―the teacher learning more than she could have ever hoped for from former students. Indeed, the expertise and support of Damián V. Solano Escolano, María del Mar Torreblanca, Lara Elizabeth Hamburger, and Grady C. Wray, and Pablo García Loaeza ensured this book would come to fruition. In particular, María del Mar joyfully dedicated weeks at a time to team up with me for forays into the field, making sure that these stories would be told for Andalusia. The shaping of this volume also took a team to complete with Mark Feddersen providing astute editorial suggestions, and Giada Mirelli, Nathan Douglas, and Licia Weber offering their keen eyes and expertise in preparing the final text and images. Finally, my unending gratitude goes to my husband, Mark, and my daughter, Anna, for their willingness to take a leap of faith, go live in Seville, and embrace the joys of living there while I carried out interviews. Our time in Seville was made forever memorable by our dear neighbor-friends, Rocío, Chema, and Violeta.

I dedicate this book to the memory of my twin sister, Jeanne, and my parents, Mary and Richard Myers. It was Jeanne’s adventurous spirit — and my parents’ belief in independence — that helped us land, as eighteen-year-olds, in Seville for the first time. To this dedication I add my siblings, Patty, Chuck, Bill, and Tom, who buoyed me with jokes and sibling power over the years this project unfolded.

Translator’s Note

The translation of oral language into a written text presents challenges. At times, speakers express emotions that are hard to capture on the written page. Colloquial expressions contain many nuances that require a thorough contextualization and comprehension of the content. Fortunately, Kathleen Ann Myers’s narration well contextualizes each participant of A Country of Shepherds, and, to my benefit, her more direct guidance in personal correspondence helped me understand and emphasize the character, tone, and register of the interviewees. Additionally, Damián V. Solano Escolano and Diego Valdecantos Monteagudo bettered my understanding of elusive colloquial and idiomatic expressions that I hope added a subtle richness to the texts. One of the most delicate areas of translation was the general description of a shepherd as “el tonto del pueblo.” The term certainly emerges in the interviews as an offensive one that carries traumatic undertones and overtones ranging from mental incapacity to a lack of higher education. Some informants, in fact, did use “lowest of the low” to describe how some people still refer to shepherds. Even though I considered terms such as “village fool,” “village dummy,” “hillbilly,” “dumb shepherd,” “ignorant,” and “uncultured,” in the end, I opted for the more broadly used “village idiot,” although it may not precisely contain all the derisive nuances that the insult infers.

As Myers and I discussed approaches to the translations of the interviews, we agreed to leave certain terms in Spanish throughout both her narration and the interviews to enliven the text and add elements of local color. Many of the Spanish terms are defined throughout the narration or in the “Pastoralism: A Contextual Background and Terminology” section and allude to specific practices, places, and professions in the Spanish context. For example, it is difficult to find acceptable equivalents for “ganadería” and “ganadero.” The term ganadería generically refers to the various aspects of livestock farming. Typically, ganadero translates as “rancher,” “cattleman,” or “livestock worker.” In the context of A Country of Shepherds, however, the term is more connected to people who care for, raise, and/or own sheep and goats. It can denote a shepherd or a goatherd, but it can also imply an owner of livestock, in a more entrepreneurial sense.

Among other terms that we decided to keep in Spanish throughout are monte, finca, and dehesa. The word monte is commonly used to refer to undeveloped public lands, more-or-less forested, often at a higher elevation, but not necessarily in a mountainous landscape. As a concept, monte also conveys notions akin to “backwoods,” “wilderness,” and “countryside.” Finca can have various definitions that include “ranch,” “farm,” “plantation,” “estate,” or “property,” but seldom do these English terms conjure up the particular image of a place where sheep and goats are raised in Spain. Therefore, the Spanish flair of finca highlights a cultural difference that I believe is appropriate. Dehesa, similarly, evades simple translation, describing a particular type of Andalusian farm that mixes extensive grazing with cleared forests of cork and olive trees. Overall, I hope that the inclusion of these and other Spanish terms help to situate the text more specifically and aid in invigorating the descriptions of these multicolored voices who help us understand the past, present, and future of pastoralism in Spain.

Grady C. Wray

List of Illustrations

All photographs by Kathleen Ann Myers (unless otherwise noted)

Fig. 0.1

Scenes from the Festival of Transhumance, Madrid (2017)

Fig. 0.2

Jesús Garzón Heydt (LOIright) with festival participants, Madrid (2017)

Fig. 0.3

Bartolomé Esteban Murillo, Adoration of the Shepherds (ca. 1650), Prado Museum, Madrid, photograph by Abraham (2010),Wikimedia, public domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Shepherd_adoration.jpg; Bartolomé Esteban Murillo, The Good Shepherd (ca. 1675), Städel Museum, Frankfurt am Main, public domain, https://sammlung.staedelmuseum.de/en/work/the-good-shepherd

Fig. 0.4

Topographical Map of Andalusia highlighting the regions featured in our case studies. “Andalusia physical map” (2023). OntheWorldMap.com, CC BY-NC, https://ontheworldmap.com/spain/autonomous-community/andalusia/andalusia-physical-map.html Labels added by Licia Weber

Fig. 0.5

Map of the vías pecuarias throughout Spain. Map by Diotime, “Principales vías pecuarias españolas” (2009). Wikimedia, public domain, https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/V%C3%ADa_pecuaria#/media/Archivo:Principales_vias_pecuarias.png

Fig. 0.6

Map of the Dehesas in the Iberian Peninsula. Map by El Mono Español (2015), Wikimedia, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Dehesa_in_Spain_and_Portugal.svg

Fig. 0.7

Payoya goats in the Sierra de Grazalema (2019); Fortunato Guerrero Lara with his Portuguese water dog, Sierra de Grazalema (2019)

Fig. 0.8

“Transhumancia.” Photo by María del Carmen García, vía pecuaria, Spain (n.d.)

Fig. 1.1

The town of Constantina, Sierra Norte de Sevilla (2017)

Fig. 1.2

Juan Vázquez Morán and Manuel Grillo (2017); Juan on his newly acquired land parcel (2019)

Fig. 1.3

Juan’s father shearing a sheep (1954). Courtesy of the Morán family archive

Fig. 1.4

Patricio Vázquez Morán and his sister, Conchi, selling homemade preserves at the Organic Market in Seville (2019)

Fig. 1.5

Caring for their growing herd of cabras floridas sevillanas are Juan Carlos Vázquez Morán (2022); Vanesa Pablo Fernández (2022); their daughter Paola (2022)

Fig. 2.1

The town of Zahara de la Sierra, Cádiz (2017)

Fig. 2.2

Pepe Millán (2019) and his farm in the Parque Natural Sierra de Grazalema (2019)

Fig. 2.3

All hands on deck as Pepe and his family work together at milking time (2019)

Fig. 2.4

A Family portrait, Sierra de Grazalema (2019)

Fig. 3.1

A view of the barn and sheep in Sierra de Cardeña y Montoro (2018)

Fig. 3.2

Fortunato and his water dog, Sierra de Cardeña y Montoro (2018)

Fig. 3.3

Manuel Guerrero watches over the flock, Sierra de Cardeña y Montoro (2018)

Fig. 3.4

Fortunato Guerrero Lara with son Javier inside the historic farmhouse (2018)

Fig. 3.5

Rafael Enríquez del Río with his daughter Isabel on their Dehesa la Rasa (2018)

Fig. 4.1

View of Marta Moya Espinosa’s dehesa and sheep near Castillo de las Guardas, Seville (2018)

Fig. 4.2

A local shepherd works for hire on Marta’s dehesa (2018)

Fig. 4.3

Iberian pigs graze on Marta’s dehesa for months each year (2018)

Fig. 4.4

Parcels of Marta’s dehesa are dedicated bio-reserves for local flora and fauna (2018)

Fig. 4.5

Marta’s mother, Carmela Espinosa Calero, in Seville (2019)

Fig. 5.1

Dehesa San Francisco in Santa Olalla del Cala, Huelva (2017)

Fig. 5.2

Ernestine with a hawk on the dehesa (2021)

Fig. 5.3

Olive trees, cork trees, and Merino sheep are the key to a healthy dehesa and, in the distance, the conference space for the “Fundación Monte Mediterráneo” (2017)

Fig. 6.1

Veterinarian María del Carmen García presents information on the benefits of transhumance to students at the Escuela de Pastores, Andalucía (2016)

Fig. 6.2

Francisco Bueno Mesa, ganadero and student at the Escuela de Pastores, Andalusia (2016)

Fig. 7.1

Zapatos tradicionales del pastoreo [traditional shepherds’ shoes] (2017)

Fig. 0.1 Scenes from the Festival of Transhumance, Madrid (2017).

Introduction

© 2024 Kathleen Ann Myers, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0387.00

Pastoralism in Spain

Every fall, Spanish shepherds herd thousands of sheep along ancient droving rights of way that pass directly through the busy Puerta del Sol in downtown Madrid, the urban heart of the city and symbolic center of Spain (marked as kilometer “0” for national highways). First granted as a system of royal rights of way throughout the Iberian Peninsula in the thirteenth century, many of these droving routes, known as vías pecuarias, have fallen into disuse. Routes have often been paved over as urban development has spread through the country. Today in Madrid, the celebration of this ancient practice of transhumance, the seasonal migration of sheep and shepherds from summer to winter pastures and back again, occurs only on one Sunday a year.

The practice dates back about 7,000 years in the Iberian Peninsula, and, in 1994, environmental activist Jesús Garzón Heydt helped bring the ancient practice of transhumance and these droving rights of way to national and international attention by establishing this one-day Festival of Transhumance in Madrid. More than twenty years later, I attend the popular festival and meet Jesús Garzón. To find him, I must wind my way through thousands of tourists and a host of international reporters who witness the lively scene. This day, over 2,000 sheep are herded by shepherds who whistle to highly trained dogs and carry the traditional walking stick, the cayado. Along the way, I see an exuberant group in striking black and white costumes with red accents dancing the traditional jota. Further down the Gran Vía, a handful of women from León wear woolen green foot-liners in their raised wooden shoes, made for the damp weather in the fields. Here, in the oldest part of Madrid, the president of the ancient shepherd guild from the Middle Ages, La Mesta, pays the symbolic fifty antique Iberian coins (maravedís al millar) to the mayor in exchange for the continued use of the rights of way.

When I finally see Jesús Garzón, he stands nearly a head taller than most of those around him and easily engages them all. For our interview, Jesús — known to everyone as Suso — suggests we move further along past the Puerta de Alcalá. He chooses a bench next to a carved stone marking the royal droving right of way at the entrance to Madrid’s central park, El Retiro. As founder of Spain’s largest cultural and activist organization dedicated to pastoralism (Asociación Trashumancia y Naturaleza), he strives to bring environmental, cultural, and political groups together at both the national and pan-European levels but also helps with concrete logistics and legal challenges faced by individual transhumant shepherds. Cultural outreach, Suso explains, is also key to the mission of making transhumance sustainable. People need to know that it helps the environment as a “máquina de sembranza” (seed-sowing machine) and an “ecosistema andante” (mobile ecosystem) by sowing biodiverse seeds, cleaning underbrush, and fertilizing land. The public can play an important role with their votes and consumer power. Public visibility facilitates policy changes.

The festival has become so successful in its public-facing mission, Suso reveals, that this year a few government officials have tried to coopt it for their own political agendas, going so far as to even change the festival date. Later, when I interview two brothers who herd their flock through the streets, I learn that the change in the festival date, and the requirement to transport their sheep out of Madrid by truck instead of by foot, means they will arrive to Córdoba ahead of the fall rains, and water will be scarce. Nevertheless, Suso insists that this Sunday is still a time to celebrate the progress of putting transhumance back on the map — both literally and culturally. Spain is the only country in the world that conserves 125,000 kilometers of droving rights of way. In a recent interview with the BBC, Suso underscores his basic view: “The planet is facing a situation of real social and economic catastrophe, but pastoralism is going to survive” (Walker 2021).

Fig. 0.2 Jesús Garzón Heydt (right) with festival participants, Madrid (2017).

Transhumance is an ancient solution to the challenge of maintaining sustainable grazing practices. It is central to the traditional practices of animal husbandry, known as pastoralism, and more specifically as extensive grazing, a system that distributes grazing and water across a given landscape. In Andalusia, it is practiced on both public lands and private pastures, including the dehesas, which are large multifunctional farms that mix extensive grazing with cleared forests of cork and olive trees. The movement of livestock from summer to winter pastures along extensive droving routes not only benefits the pastures and aids with water retention; it also promotes biodiversity through the fertilization and dispersion of seeds, as well as with cleaning underbrush and overgrowth. Thus, pastoralism is one of the most sustainable food production systems, and transhumance was the primary form of animal migration for millennia. (Definitions and further information about specialized terms within Pastoralism can be found below in “Contextual Background and Terminology.”)

Even as the traditional practice wanes, public awareness of the need to protect and preserve the official droving roads and transhumance itself has proved invaluable. Although very few individuals in Spain are still directly involved with these practices, even the average person has likely heard of or enjoys the recreational use of the vías pecuarias, or else appreciates the traditional foods created by shepherds that have been popularized in the national cuisine. Many Spaniards also know something about the ecological benefits of transhumance. While most of the population is now urban, rural family roots still tie individuals to their towns (pueblos) that their grandparents or great grandparents inhabited, and many return in the summers or for holidays. These visits maintain and strengthen a connection with the land, the animals, and this traditional livelihood. And there still is a major romantic appeal: the outfits, the food, the music, the walking!

During the last twenty years, new policies protecting the traditional ways have been introduced, and related cultural production has exploded. Spanish society has embraced the ancient practice of transhumance and shepherding in general as foundational to Spanish national heritage. Museums and festivals devoted to shepherding practices, like Madrid’s Festival of Transhumance, have sprung up everywhere. Best-selling novels, traditional music, news stories, new rural museums, and documentary films about traditional practices underscore how socio-cultural memory, place, and practice are deeply intertwined. This decades-long boom of cultural production has contributed to a more widespread visibility of Spanish pastoralism.

When I first began research for A Country of Shepherds in 2015, I surveyed the extent of these cultural activities in Spain and found that there are more than twenty-three museums and interpretative centers fully or partially related to transhumance. Nearly forty festivals occur either annually or biannually. Hundreds of videos, from feature-length documentaries to shorter informational clips, are easily accessible on the web. More than twenty associations related to transhumance and extensive grazing practices have been formed, some with a significant web presence. In June 2016 alone, more than fifty magazine and newspaper articles were published about the movement. And, while the traditional oversized wool pullovers and giant leather leg protectors may not be used by most shepherds now, this traditional dress retains an important place in Spanish cultural memory. In February, during Carnival, young children choose costumes, and inevitably there are a few traditional shepherds in the mix. The children “play shepherd” for a day, donning the trademark wide-brimmed hats, leather accessories, and wooden shoes (see Fig. 7.1).

The cultural resurgence of interest in pastoralism and transhumance has also attracted widespread interest across Europe and the U.S. Popular journals and media events held in France, England, Germany, and the U.S. have brought this tradition to international audiences. In the U.S., for example, such magazines as The Atlantic and Bloomberg and other leading media outlets, such as The New York Times and the BBC, have published articles and produced programs on transhumance. This parallels a more widespread Western interest in grazing practices and the popularization of materials about it, such as James Rebank’s New York Times-Bestseller The Shepherd’s Life: Modern Dispatches from an Ancient Landscape (2015). The revitalized pastoral narrative, combined with environmental programs and government initiatives, has amplified a new awareness of traditional grazing practices. Andalusia’s Shepherd School (Escuela de Pastores), for example, received the European Union Award for best use of funds for rural development (2015). In 2023, UNESCO added Spain to its list of representative countries in which transhumance is Immaterial Cultural Heritage of Humanity, stating:

An ancestral practice, transhumance stems from a deep knowledge about the environment and entails social practices and rituals related to the care, breeding and training of animals and the management of natural resources. An entire socio-economic system has been developed around transhumance, from gastronomy to local handicrafts and festivities marking the beginning and end of a season. Families have been enacting and transmitting transhumance through observation and practice for many generations. Communities living along transhumance routes also play an important role in its transmission, such as by celebrating herd crossings and organising festivals. The practice is also transmitted through workshops organised by local communities, associations and networks of herders and farmers, as well as through universities and research institutes. Transhumance thus contributes to social inclusion, strengthening cultural identity and ties between families, communities and territories while counteracting the effects of rural depopulation. (

https://ich.unesco.org/en/RL/transhumance-the-seasonal-droving-of-livestock-01964

)

Pastoral Practices and Shepherds’ Narratives

Indeed, this cultural interest in an ancient way of life is how I first came to the topic. As a college student studying history in Spain in the late 1970s, I was fascinated by shepherds herding sheep and goats, sharing roads and hiking trails with me as I traveled around the Iberian Peninsula. But it was not until twenty years later in the 1990s, after becoming a scholar of how life stories reveal cultural practices from early modern times, that I first stopped to talk with a shepherd. As we hiked along a trail in the Northern Picos de Europa, he seemed to appear out of nowhere. He spoke poetically about the mountains and how they seem to hide behind clouds and mist, seeing fit to show themselves only on rare occasions as they did on this hot cloudless day. He also spoke of the trials of solitary life in a field living in his traditional shepherd’s hut, suffering from a fever with no one to take care of him, much less his sheep.

Many years later, I came back to his story with a desire to learn more. While doing archival research in Seville in 2015, I had seen shepherds moving flocks through semi-arid land on the outskirts of town in the intense early spring sun. I watched frequent television programs and read nearly weekly articles that focused on transhumance. I listened to a few friends talking about their transhumance vacations in Northern Spain. What had been a distant, rural attraction for me as a student-tourist had now become part of a popular cultural scene forty years later. As I mused about these stories and the growing cultural interest in them, a friend offered to introduce me to a shepherd she knew from the Sierra Norte, about an hour from Seville.

Juan Vázquez Morán practiced transhumance along the vías pecuarias for decades, but he recently left the practice to work in extensive grazing, which continues traditional ecological and seasonal use of lands and water but does not necessarily involve migration of livestock for long periods of time to other areas. Juan spoke of growing up as a shepherd and loving his work but also of facing endless challenges that society and governmental policies add to an already difficult vocation. “They ask for this form, that form, and more forms on top of that. You’ve got to get a guidebook before you start doing transhumance, or they don’t let you do it.” What is more, over time, the droving routes leaving from Constantina became impassable, overgrown with underbrush and spiny bushes from lack of use. He reports: “The routes are all going away because livestock doesn’t come through here anymore to eat any of the brush; you just don’t see any animals come through to clear anything.” In another interview, long-time transhumant shepherd Fortunato Guerrero Lara added to Juan’s list of challenges. Markets for sustainable wool, meat, and milk have weakened with modernization, globalization, and climate change. And all too often, regional, national, or EU regulations and bureaucracy challenge the ability of people who work with livestock to make ends meet. Few young people want to become shepherds because of the long hours and hardships involved. These are realities that simply supplying cell phones and GPS to shepherds cannot mitigate. Not only are transhumance and pastoralism themselves in transition, but so are a host of other factors: rural depopulation, consumers who abandon local products for supermarkets, new EU methods of calculating pasture lands and funding, conflicts in regional restrictions on marketing local products, and access to public pastures.

Yet as Juan and Fortunato weigh the current challenges and look toward the future, they, like the founder of Madrid’s Festival of Transhumance, both see educating society as the key to changing these patterns. They even suggest that a foreigner — from a country infamous for exterminating many ancient practices and peoples — might give the story a fresh, more urgent perspective. As I began interviewing more widely, this message was repeated frequently. María del Carmen García, a veterinarian who travels often with Jesús Garzón to photograph shepherds on long treks across Spain, comments: “We’re lacking a global view, someone who can share our heritage beyond what’s typical folklore.” An alumnus of the Escuela de Pastores who has also trained in France, Paqui Ruiz observes how working from an outsider’s perspective is key to transforming things from within. Ana Belén Robles Cruz, a researcher at Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas (CSIC), believes outsiders can help “raise public awareness” by breaking the stereotype of shepherds as “the ones who always make the sacrifice” or “the village idiot.” She argues: “You have to put them in the spotlight.” Whether shepherd, activist, or scholar, all urged me as an outsider to get the word out, especially about Andalusia. Far fewer stories and campaigns have focused on Andalusia, yet it is at higher risk than many other parts of the peninsula for dramatic climate change. Every person I interviewed delivered the same message: a resurgence in pastoralism as a sustainable food system can help mitigate climate change and rural depopulation, but, to achieve this, consumers need to be better educated and support the true value of shepherds’ products, while governments need to greatly reduce subsidized industrial farming.

As I interviewed shepherds and their advocates, it became clear that they are also trying to reverse a trend set in motion between 1970 and 1990, when Spain witnessed the decline of Franco’s dictatorial policies and saw the rise of an experimental young democracy. During this transition, Spain’s borders opened increasingly to global capitalism, bringing a flood of tourism and, with it, new models of consumption. Over the decades the supermarket model of more prepared foods and cheaper prices has edged out neighborhood markets and hurt the small-scale production economy. People who work with livestock and shepherds say they now depend less on neighbors and more on tourists and elite consumers in the cities: those willing to spend more to know where their food comes from and how it was produced. Two themes recur in nearly every interview I conduct, whether with a shepherd, farmer-owner, or advocate: the need for government regulation to help local sustainable farms and dehesas thrive instead of hindering the marketing of their goods and the need to educate consumers about the “added value” of these products.

Talking with shepherds, I began to realize that another story — not just about the waning practice of transhumance — needed to be told. Larger issues, such as rural depopulation, and broader agricultural and land management practices provide a fuller picture of pastoralism today. While transhumance is the most ecologically sustainable model, broader perspectives show how low-impact grazing practices can help agriculture and pastoralism establish more resilient models. Beginning to correct my own misconceptions about shepherding, I decided to collect contemporary narratives about the practice from the point of view of both practitioners and advocates and to place them in dialogue with the trajectory of historical practices and narratives about pastoralism. The interviews flesh out four general gaps in our knowledge: they provide a fuller portrait of Andalusia (a region often overlooked in pastoralism); of the extensive networks required for pastoralism today (family, collective organizations (plataformas), government, scholars, consumers); of the changing role of landowners in this picture; and of the trend toward shepherds becoming entrepreneurs working for themselves instead of either for or along with farm owners. This more complete picture allows us to glimpse both the power of tradition and the call to innovation and resiliency. The future of rural life in an environment that has benefitted from millennia of sustainable grazing practices now hangs in the balance.

Historical Practices and Cultural Narratives

For centuries, shepherding and the movement of flocks has held great historical, economic, and cultural importance in the Iberian Peninsula. As early as 1273, King Alfonso X appointed the first association, La Mesta, to try to regulate it, and over the centuries shepherding evolved into a complex legal, economic, social, and cultural practice. Precious Merino wool became a staple for an emerging market economy in fifteenth-century Iberia. By the late medieval times, the figure of the shepherd had also become central to the formation of emerging socio-cultural identities. Shepherding was the main economic activity in early modern Iberia as the low population density of the peninsula, the skirmishes between Christian and Muslim-ruled regions, and the semi-arid environment in parts of the south made raising livestock more profitable than establishing permanent agriculture. Later, with the expulsion of Muslims, Jews, and other “racially impure” others, cultural narratives turned to pastoralism as a symbol of a collective identity for Christian Iberia in a time of racial anxiety about religious and ethnic difference.1 This process continued to evolve throughout the nineteenth century as pastoralism became conflated with the idea of national culture, reflecting a certain nostalgia.

Fig. 0.3 Bartolomé Esteban Murillo, Adoration of the Shepherds (ca. 1650), Prado Museum, Madrid, photograph by Abraham (2010), Wikimedia, public domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Shepherd_adoration.jpg; Bartolomé Esteban Murillo, The Good Shepherd (ca. 1675), Städel Museum, Frankfurt am Main, public domain, https://sammlung.staedelmuseum.de/en/work/the-good-shepherd

While twentieth-century processes of modernization like the transportation of livestock by train and by trucks and the mass production of cheeses and meats drastically reduced the practice of transhumance, the symbolic importance of the shepherd persisted. Often following an early modern pattern recorded by Miguel de Cervantes in Don Quijote (1605; 1615), the image of the shepherd vacillated between idealization and marginalization. During the Spanish Civil War and the first decades of Franco’s dictatorship, for example, the “humble shepherd” was re-appropriated in cultural production to essentially turn back the clock on modernization and pan-European processes. Later, as the state discourse of Francoism promulgated developmentalism and promoted modernization, this trend reversed again. The push to modernization then accelerated the abandonment of rural areas and pastoral traditions, which fueled the stereotype, in Ana Belén Robles Cruz’s words, of the “shepherd as the village idiot.”

Even in the first years of Spain’s rapid transition to democracy (ca. 1975–82), pastoralism and the movement of flocks along traditional routes continued to be viewed as anachronistic and an impediment to the modernization of waterways, highways, and urbanization, yet this attitude would soon change. As the new democracy matured into the late twentieth century, the past was “repackaged” for the 1992 Quincentennial. New socio-political movements looked again to autonomous regional traditions in the face of globalization and entrance into the European markets. The year marked a symbolic turning point for Spain as it emerged on the international scene as host of the Olympics (Barcelona), the World’s Fair (Seville), and the Cultural Capital of the European Union (Madrid). New debates, political actions, and cultural narratives about Spain’s pastoral past and present emerged. A movement emerged and began to revitalize ancient shepherding practices and narratives about pastoralism, identifying them as integral to national culture.

At the turn of the twenty-first century, this transformation gained increasing influence over policy making and environmental activism. The raising of traditional Iberian livestock began to be celebrated for its contribution to the preservation of rural landscapes, biodiversity, and ways of life, to the point that the Spanish state now welcomes shepherds into national parks as a strategy for conserving the Iberian wolf, vultures, and other endangered “natural enemies” of sheep that were all once ruthlessly targeted by the Franco regime for extermination. Regional governments also began to fund programs to train a new generation of shepherds and recognize new justifications for grazing sheep and goats, such as fire prevention. National policies established new protectionary laws for rights of way. Supporters in non-government sectors also joined a larger movement fighting for the survival of sustainable, small-scale agriculture and greater regional autonomy.

Yet even as local, national, and international interest grows, the challenges continue. Many shepherds I interviewed are retiring without replacements. Recent EU regulations about the movement and sale of animals restrict the viability of the practice by making it more costly to compete with large-scale production. Consumer tastes continue to shift, with the consumption of more pork and beef instead of lamb, and more cheeses manufactured and marketed by industrial agricultural interests. In addition, the use of wool has declined as preferences for synthetic “high-performance” fabrics increase. Even as the population generally understands the deep cultural and environmental benefits of traditional practices, there is still the gap just like the one Cervantes depicted in Don Quijote between the idealized and real shepherd. Shepherds are no longer portrayed as symbols of Christian humility but rather as defenders of a valuable cultural geography integral to the national Spanish patrimony.

Nevertheless, these same guardians of tradition and sustainable practices are often still the targets of social prejudice, as we will hear in many of the cases studied below. Indeed, the gap between urban and rural remains. Until recently, city dwellers, who love visiting pueblos and enjoy a countryside dotted with shepherds and their flocks, often balk at interacting with locals or at the thought of making a life for themselves and their families in a small pueblo. For their part, the rural residents often complain of the lack of respect they get from visitors, which aggravates their own frustration of dealing with limited social services and economic opportunities. Small-town residents also experience resistance from their own neighbors to changing gender roles in shepherding. The country-city divide accelerates the loss of traditional shepherding practices and exacerbates the already widespread depopulation throughout Spain.

Still, some positive changes are observed by my informants. They often remark on the promise of a new generation of neo-rurales, young people leaving the city to live and work in the countryside, who are exploring new ways to work within traditional vocations like pastoralism. One shepherd we will hear from below (and who prefers to simply be called Daniel) expresses “the need to get out of the city, the fast-paced rhythm of today’s society, and everything that has to do with urban life.” He decided to try out shepherding, a profession his uncle had to abandon years ago, because “it motivates me to live out his dream.” One of the shepherds we will hear from remarks that he enjoys the psychological challenge of working with animals and the environment and of acquiring the in-depth knowledge necessary to carry out his work. It allows him to “honor the values of people who live freely, far removed from the ‘usual’ expectations.”

This is where my project and experience as an outsider interviewing practitioners and advocates of pastoralism comes in. As people sought to explain to a foreigner what they did and why, I began to piece together a more complex picture of a dynamic, resilient practice that may help suggest a way forward.

Life Stories and Pastoralism: Method and Scope

The centerpiece of A Country of Shepherds are the oral histories that provide a glimpse of how the people working in pastoralism articulate the meaning of their work as shepherds, farm owners, and advocates. Although this project draws on extensive scholarship about pastoralism in Spanish Iberia, my focus is the living archive created by dozens of informants who reveal their deep connections with the ongoing practice, regulation, and celebration of both traditional and innovative practices in Western Andalusia.2

To date, no study has closely examined the shepherds’ life stories within the context of pastoralism in Andalusia and its broader relevance to the more critical role of extensive grazing. While transhumance has been a topic of historical and anthropological study since Julius Klein’s foundational study of the practice (1920/1981), more recent scholarly production has tended to explore the important ecological impact of transhumance and its intersection with society (Gómez-Sal, 2004; Manzano Baena 2010; Garzón Heydt 2004). Just a handful of articles study pastoralism and cultural narratives (Alenza García 2013; Acuña Delgado 2012; Cruz Sánchez 2013; and Rodríguez Pascual 2001). Most recent work, such as that by such scholars as Yolanda Mena Guerrero and her collaborators, focuses more broadly on specific practices and benefits within pastoralism to raise awareness about it through public education (2015), national patrimony (2010), and rural development (2007). Elisa Otero-Rozas studies the notion of traditional ecological knowledge that is integral to pastoralism in Spain (2019). Although A Country of Shepherds has strong ties to work being done by scholars and government agencies on sustainable practices and the long-term benefits of extensive grazing in Spain, it locates itself within the particular Andalusian social and geographical context. I argue that hearing individual life stories and placing them in dialogue with the broader work on pastoralism reveals a dynamic movement that at once illuminates a rich heritage and suggests sustainable ways forward.

The main interviews offered here were carried out onsite at various farms and pastures from 2015–2018 (with updates in 2021–2022) and took place with my cultural interpreter, María del Mar Torreblanca. I collected the narratives in five different regions of Western Andalusia — within a couple hours’ car drive of Seville — which presents a special case within the larger study of pastoralism in Spain. The mountainous terrain creates greater climatic diversity than other regions. Although there are many semi-arid regions, in general it is more verdant than areas of Eastern Andalusia. The ancient landscape is dotted with unique areas of public mountainous pasturelands of the Mediterranean area (monte mediterráneo), as well as private dehesas. In addition, the whole region has generally been overlooked by people studying the tradition. The cases I study highlight a range of land types, land uses, and livestock breeds across five provinces in Andalusia. We move from the monte mediterráneo of the Sierra Norte (Seville) and the Sierra de Grazalema (Cádiz), to the Sierra de Cardeña y Montoro (Córdoba-Jaén), the Sierra de Jaén, and the Sierra de Aracena (Huelva). We also visit three dehesas in these areas. Here, we see the breeding and raising of protected species that have been developed over centuries to adapt to the highly specific microclimates, including traditional Merino and Segureña (Esguerra) sheep breeds and endangered Payoya goats.

At the core of this study is a “living archive”: the nearly sixty interviews of shepherds, policy makers, educators, community organizers, and landowners. I have distilled these interviews into a handful of in-depth life stories in which we see how none of these Andalusian farms, families, and endeavors exist in isolation. The six case studies offer a glimpse into how those most involved in the ongoing practice, regulation, and celebration of shepherding articulate both traditional and innovative ideas about their work. While most scholarship on the subject maps the routes, economic patterns, and specific historical events or practices related to transhumance, this book presents the varied people, places, voices, and landscapes reflective of a broader pastoral past and present that focuses, in particular, on the Western Andalusian geographies. It is a snapshot in time filtered through the lens of my own experiences and my own process of discovery. At times, it was my very “outsiderness” that seemed to allow people to tell their stories more fully. They often filled in information that may be common knowledge to someone who grew up in the region. They mentioned feeling freed from preconceived notions about their work and lives. Indeed, my presence — and my curiosity as well as my ignorance — often were the source of a good deal of laughter and light-hearted teasing.

I open each case study with an overview of current practices exemplified in the section before inviting readers to join our visits to the places and people who live and work as farmers, shepherds, and landowners. During each visit, we hear how experiences from early childhood influence their chosen vocations today. These personal stories reflect larger forces and constraints, including family heritage, social norms, economic opportunities, and even global climate change. In each chapter, I include short selections that highlight my informants’ concerns in their own words. Key to this process, however, was my decision not to carry out formal interviews in a question-and-answer format but to allow farmers and shepherds to show us around their own pastures and farms and talk about their life stories and practices. As we moved about, I recorded our conversations and transcribed them later in order to maintain a strong sense of “walking about” and interacting with other people, the animals, and the landscapes — hiking to an outcrop to see if the goats arrived to the valley, returning to the barn for milking time, driving to remote grazing areas, helping catch a squealing pig that escaped, stopping dead in our tracks when a pair of dead day-old lambs are spotted, and returning to a working farmhouse for a beer and a tapa in the heat of the day.

In each visit, the informants explore fundamental questions, such as: What is my role in keeping this practice alive? What do we gain from it and, just as interestingly and increasingly, what does society gain? And perhaps the most important question of all: How do we see the future, and what do we need to do to keep pastoralism alive and attract new generations to it before it is too late? Finally, every case study ends with a brief update carried out by phone or Zoom eighteen months into the COVID-19 pandemic (November 2021) and, in some cases, a final in-person meeting to go over the manuscript with each contributor in June 2022. The pandemic only further underscored the essential role of these workers and their vulnerability in the current system.

Fig. 0.4 Topographical Map of Andalusia highlighting the regions featured in our case studies. “Andalusia physical map” (2023). OntheWorldMap.com, CC BY-NC, https://ontheworldmap.com/spain/autonomous-community/andalusia/andalusia-physical-map.html Labels added by Licia Weber.

New Pathways: Overview

The six case studies highlighted here reflect an overarching story of people grappling with changes in traditional agricultural practices, changes felt not just regionally but nationally and even globally. Within these limits of time and geography, a surprising richness emerges of both common denominators among people working in pastoralism and the variety of new and innovative approaches to the traditional practice. Taken together, we see transitions from traditional to new models of transhumance, as well as a turn to the importance of extensive grazing in general. We meet a full range of participants, from shepherds to farm owners and their families, and see examples of both generational and gendered change.

The first three cases focus on men who have worked in shepherding for decades, often as an inherited profession. Each has found ways to keep their ancestral practices alive and to bring in family members and others along the way. These cases illustrate entrepreneurial skills that these men and their families use to move in new directions, such as expanding into agrotourism, taking advantage of European Union funds, and exploring new roles with landowners. The two cases that follow focus on women who own dehesas but come from very different backgrounds. One woman is working with her inheritance of a functioning dehesa. The other is a foreigner now working in Andalusia on local and pan-European initiatives to protect the natural heritage of the dehesa and pastoralism. Each describes the steep learning curve she faced and, in some cases, the challenges of working and gaining respect in a traditionally male profession. The final chapter surveys the collective story told by a wide range of people involved in the social movements and platforms that support pastoralism in myriad ways, including financial backing, knowledge, partnerships, and — ultimately — resiliency. These interviews help us understand the larger context for the individual life stories of the first five chapters.

The first case study explores the story of Juan Vázquez Morán, a traditional shepherd who adopted his own father’s profession and practiced transhumance on foot outside of Constantina (Seville) and now has his own small sheep and goat farm. For both of our interviews, Juan’s retired shepherd friend Manuel Grillo joins us. Their dynamic banter reveals the tremendous challenges faced over three generations. Even as they often joke with each other, they share stories of the sacrifices they both made — decades of economic hardship, living alone in the countryside for months at a time, and the social marginalization of tending sheep for rich landowners — even as society, in theory, praises the shepherd. The two friends also note, however, the many changes to their way of life. After years of saving his earnings, Juan has been able to buy a small parcel of land on a hilly outcropping where he tends his own animals each day before and after working as a shepherd for a nearby farm owner. He remarks happily: “I’m free, kinda like a snail that carries everything on his back and needs very little. It’s not so much that it’s good land, but it’s your own, and no one around here is gonna tell you to leave.” Further, he and his family are now able to live year-round in town, and his daughter is studying for a nursing degree. Juan recognizes how society both depends on his work and often disdains it. While Juan stayed with the family profession, his youngest brother, Patricio, did not grow up with shepherding but loves the landscapes and community they both grew up with. As an ambitious entrepreneur, he has established a gourmet preserves company with the abundant local fruit, which he markets in Seville and London — and to weekend tourists in Constantina. A few years ago, Patricio opened a coffee shop that now serves Juan’s cheeses, and he currently has plans for an agrohotel. This current venture will include a partnership with his nephew’s family, who recently began raising goats. They hope that within a year they will have enough goats to be eligible for EU subsidies and to dedicate themselves full-time to the business. Taken together, the sons and grandsons of a transhumant shepherd reveal how they have stayed attached to their home region but also made a living for themselves through new practices.

The second case study takes us to an area just outside Parque Natural de la Sierra de Grazalema, near the tourist destination of Zahara de la Sierra. Here we visit Pepe Millán and family, who raise both Merino sheep and Payoya goats native to Grazalema. The family demonstrates the highly-developed skills perfected over hundreds of years needed to succeed at shepherding in a challenging environment, as well as the cost — both economic and social — of continuing to work in the profession. Their stories also highlight new roles for people working with livestock. Pepe is now a mentor and spokesman for a new generation of shepherds-in-training and for a broader public that views programs in which he is featured, such as the documentary La buena leche and the popular television program Volando voy. On the day of our visit, we follow the daily milking routine and the process of resettling the herd through the rocky terrain. We also hear about the challenges the family has faced to keep afloat economically, as well as how things have changed for the next generation. Pepe’s daughter Rita did not initially want to continue in the profession, but she is now an entrepreneur in her own right. She has secured government subsidies for their operation, which includes the endangered Payoya goats, and has launched a local cheesemaking and delivery service. We hear about the past and the future as the family expands and the world changes.

The third case study focuses on a shepherd, Fortunato Guerrero Lara, who continues to practice transhumance and works alongside his father and son. He also wears many other hats. Fortunato’s family raises Segureña sheep on public and private land and practices transhumance by truck, moving the flocks from winter pastures of Sierra de Cardeña y Montoro (Córdoba) outside Marmolejo to the summer pastures of the Sierra de Segura outside of Santiago-Pontones (Jaén). On the day we visit, he welcomes us, saying he hopes we get word out “so society will understand what a shepherd does nowadays. We manage land that has high environmental value.” As we follow him around during birthing season, we see him working his flocks and meet his own father, as well as his son who intends to stay in the family profession — a highly unusual choice today. We also visit a man Fortunato calls his “collaborator,” the landowner Rafael Enríquez del Río, who hires Fortunato to manage and protect his dehesa and area of forest. During our visit, we talk with an array of other people Rafael and Fortunato work with to develop a multifunctional dehesa beyond shepherding: beekeepers, lumber thinners and harvesters, and hunters. As we listen to their discussions onsite, we hear of the economic-environmental vitality and balance involved in multi-functional land use. Fortunato himself is also a valued advocate and spokesman for shepherds and others in livestock entrepreneurship, and his case highlights the many other tasks that livestock workers take on now because they often can’t make a living for a family without outside work. And Rafael, as a conscientious landowner, plays a critical role in stewardship, creating opportunities for professionals with expertise and a shared vision for a sustainable future.

After these first three case studies of livestock professionals (ganaderos), who not only tend to flocks of sheep and goats but recently have created their own small livestock businesses, we look more closely at the role of the owners in keeping extensive grazing and pastoralism viable. These cases also highlight a newer trend of women taking a more active role in the profession.3Marta Moya Espinosa, the subject of our fourth case study, inherited a dehesa in the Sierra Norte and large flock of Merino sheep from her father, but for years she left it in the hands of others while she raised a family and managed one of Seville’s prestigious private country clubs. Recently, she made the monumental decision to leave this lucrative, sixty-hour-a-week job and now devotes an equal amount of time to understanding her inheritance and learning to become a conscientious, knowledgeable farm owner. She helps to oversee the day-to-day operations by working alongside her shepherd-manager from dawn to dusk and is exploring new initiatives to revitalize the ecosystem. As we tour this working farm, Marta discusses the many challenges she faces with learning about the daily care of animals, finding shepherds, helping the dehesa recover from a damaging forest fire, and understanding often volatile government policies — all while working as a woman in a traditionally male world. Marta works to train and keep farmhands in a radically different society than when her mother was helping run the farm in the 1950s as the new wife of a landowning farmer. To get a sense of life on the dehesa in the mid-twentieth century, Marta introduces us to her eighty-year-old mother, Carmela Espinosa. While Marta talks about learning how to work with livestock, finances, and shepherds today, her mother reminiscences about the hardships and triumphs of running a large household with eight children on a rural rustic farmhouse during the difficult postwar years. Both women experienced the privileges of the traditional landowning class of these farms and dehesas, as well as the challenges of trying to both harness and change traditions.

Another farm owner with a very different background and a broad European resonance is the focus of the next chapter. Ernestine Lüdeke was born in Germany, but she has adopted Andalusia as her own. Ernestine began working in Spain shortly before the 1992 World Expo in Seville and soon became involved in environmental issues. By about 2000, she and her husband had established the “Fundación Monte Mediterráneo”, an organization dedicated to protecting Andalusia’s delicate ecosystem and to championing new initiatives based on traditional practices. They decided to house the Fundación on a nearly abandoned dehesa they bought outside of Santa Olalla de Cala in the Sierra de Aracena in the westernmost side of the Sierra Morena (Huelva). As Ernestine walks us around the Dehesa San Francisco, we hear how they have coaxed the dehesa back to life with a variety of plantings and raising livestock, centered around a flock of Merino sheep that are raised with transhumant practices. As part of the tour, we visit the educational center on the property and hear about regional and international teaching initiatives. The work of Ernestine and the Fundación showcase the intersection of land and livestock, as well as of traditional and innovative practices with public and private initiatives. Later, we hear from one of her trainees, Daniel, whom she has now hired as her manager-shepherd. Ernestine has the resources, knowledge, and drive to influence a wide circle of farm owners, shepherds, policy makers, and consumers. Her broad-reaching work focuses on practical applications rather than naïve romanticism and resonates throughout the region and even internationally.

Our last chapter shifts gears to follow a narrative thread suggested by Ernestine with her “Fundación Monte Mediterráneo”, as well as everyone we interviewed. Here, we take a closer look into the many collective organizations, or plataformas, that support the shepherds’ work. In our interviews, we hear from people in three main areas: 1) ganaderos and other professionals working with collective organizations to support transhumance and extensive grazing; 2) university-trained professionals based at public institutions and working to promote pastoralism through, for example, the use of grazing for fire prevention and the teaching of skills for cheesemaking; and 3) primarily government-sponsored programs, such as the popular shepherd schools, which train a new generation. Among the people interviewed here are a few of the individuals who have been on the forefront of these movements for decades, including Jesús Garzón Heydt, Paco Casero, and Yolanda Mena Guerrero, along with newer voices, such as Maricarmen García and Paco Ruiz. Each works collaboratively with a host of shepherds and ganaderos, government agencies, non-governmental organizations (NGOs), and grassroots collectives striving to ensure the resiliency of pastoralism in Andalusia and beyond.

Overall, these case studies offer multiple points of view from both traditional shepherds and the new model of ganadero-shepherds, and their families, as well as from farm owners trying to be conscientious stewards of their land and from advocates creating new resources for practitioners of pastoralism. They all play key roles in the functioning and longevity of pastoralism. Together, their stories reveal the hope and frustration, the nostalgia and excitement, of working in a profession dating back millennia and now in the process of profound change. We learn how those working closely with pastoralism are concerned equally about the people, animals, and landscape itself — the elements for sustainable pastoral systems. As they describe their work and lives, they dialogue with cultural narratives about shepherds and Spain that increasingly link them to discussions about environmentally sustainable practices and food systems. All articulate a sense of urgency related to their situation, as well as a set of possibilities for the future.

This project began with myriad preconceptions (mostly my own misconceptions) about pastoralism in Spain. I share here how my perspective has broadened over time — a process that is still ongoing. For this reason, I often use the present tense and a plural form to invite the reader along with me in my journey through different pastoral spaces over a period of about five years. My goal is to bring the human face of pastoralism to a broad audience, allowing the informants interviewed and the images gathered to tell the story of an ancient practice in the midst of transition. My hope is that, as we hear the complex dynamics and practices involved in traditional pastoralism as well as glimpse the broad social movements that support it, we will see how the stereotype of a solitary shepherd working in