Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

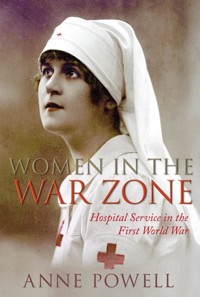

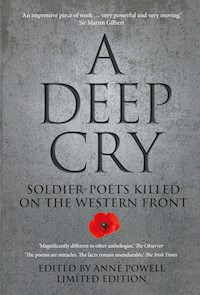

The lives, deaths, poetry, diaries and extracts from letters of sixty-six soldier-poets are brought together in this limited edition of Anne Powell's unique anthology; a fitting commemoration for the centenary of the First World War. These poems are not simply the works of well-known names such as Wilfred Owen – though they are represented – they have been painstakingly collected from a multitude of sources, and the relative obscurity of some of the voices makes the message all the more moving. Moreover, all but five of these soldiers lie within forty-five miles of Arras. Their deaths are described here in chronological order, with an account of each man's last battle. This in itself provides a revealing gradual change in the poetry from early naïve patriotism to despair about the human race and the bitterness of 'Dulce et Decorum Est'.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 751

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

for JEREMY

With my love as always

… I sang to the long hope of my life

And the magic of the aspiration of youth;

The passion of the wind and the scent

Of the lightning of the path

Ahead were in my poem.

My muse was a deep cry

And all the ages to come will hear it,

And my rewards were grievous violence;

And a world that is

One long bare winter without respite…

Extract from ‘The Hero’ by ‘Hedd Wyn’

(Private Ellis Humphrey Evans,

Royal Welch Fusiliers). Translated from the Welsh

… The whole earth is the tomb of heroic men;

and their story is not graven only on stone over

their clay, but abides everywhere, without visible

symbol, woven into the stuff of other men’s lives.

Pericles’ funeral oration from Thucydides.

The Land Occupied as British War Cemeteries in France is, by a Law of 29th December 1915, the Free Gift of the French People for the Perpetual Resting Place of those who are laid there.

The Land in Belgium Occupied as British War Cemeteries or Graves has been Generously Conceded in Perpetuity by the Belgian People under an Agreement made at Le Havre on August 9th 1917.

From the Commonwealth War Graves Commission’s Cemetery and Memorial Registers.

CONTENTS

Title Page

Epigraph

Acknowledgments.

Introduction.

The Soldier-Poets in chronological order of their death.

Map: 1. North-East France and Belgium – General.

1915

1916

1917

1918

Alphabetical list of Soldier-Poets and Poems.

Dates of Major Battles on the Western Front.

Map: 2. a. Ypres Group – Cemeteries.

b. Ypres Region.

3. a. Arras Group – Cemeteries.

b. Arras Region.

4. a. Somme Group – Cemeteries.

b. Somme Region.

5. a. Cambrai Group – Cemeteries.

b. Cambrai Region.

6. St. Quentin Region.

Appendices:

A. List of Regiments.

B. List of Cemeteries and Memorials.

Bibliography.

Copyright

Maps 1–5 by David Goudge.

Map 6 by Jeremy Powell.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I would like to thank the following who have kindly given permission to reprint copyright material:

Mr. Winston S. Churchill, M.P., for an extract from a letter from his Grandfather, Sir Winston Churchill, to Katherine Asquith; Messrs. Faber and Faber Ltd., on behalf of the Ezra Pound Literary Property Trust, for ‘Trenches: St. Eloi’ reprinted from Ezra Pound’s Collected Early Poems; Mr. Dominic Hibberd and Messrs. Chatto and Windus for permission to quote ‘Anthem for Doomed Youth’ and ‘Dulce et Decorum Est’ from Wilfred Owen War Poems and Others, Edited with an Introduction and Notes by Dominic Hibberd, Chatto and Windus 1973; and for permission to quote ‘Anthem for Doomed Youth’ and ‘Dulce et Decorum Est’ by Wilfred Owen from The Collected Poems of Wilfred Owen, Copyright 1963, by Chatto and Windus, Ltd. Reprinted by permission of New Directions Publishing Cor; The Hon. John Jolliffe for extracts from his book Raymond Asquith Life and Letters, Collins 1980; Mr. David Leighton for four peoms by Roland Leighton; Mr. Martin Middlebrook for an extract about Private Harry Streets, from The First Day on the Somme, Allen Lane 1971; The University of Minnesota Press and Professor Samuel Hynes for extracts from T.E. Hulme’s ‘Diary from the Trenches’ from Further Speculations: T.E. Hulme Edited by Sam Hynes, University of Minnesota Press, 1955; Lord Norwich and Mr. Michael Shaw-Stewart for an extract from a letter from Patrick Shaw-Stewart to Lady Diana Manners; Dr. Conor Cruise O’Brien for the last letter Tom Kettle wrote to his wife; The Earl of Oxford and Asquith for his father’s Belgian Railway verses; Oxford University Press for extracts from Wilfred Owen Collected Letters: Edited by Harold Owen and John Bell, OUP, 1967; Messrs. Peters Fraser & Dunlop on behalf of the Julian Grenfell Estate for three extracts from Julian Grenfell his life and the times of his death 1888–1915 by Nicholas Mosley, Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1976; Mr. Tomos Roberts, Archivist, University College of North Wales, Bangor, for extracts from his article on ‘Hedd Wyn’ published in Barddas; Mrs. Myfanwy Thomas and The National Library of Wales for extracts from the 1917 Edward Thomas letters; Mrs. Myfanwy Thomas and the Edward Thomas Collection, University of Wales College, Cardiff, for an extract from a letter written by Edward Thomas to his daughter, Myfanwy.

The Vera Brittain material from her World War I Diary, Chronicle of Youth is included with the permission of her literary executors and Victor Gollancz, publisher.

I am deeply grateful to the following for research on my behalf and for their help and kindness in various ways:

Rosemary Barker; Glenda Carr, Academic Translator, University College of North Wales, Bangor; Wendy Chandley, Archivist, Tameside Archive Service; The staff of the Commonwealth War Graves Commission and in particular, Norman Christie and the Tracing Team; Jenny Hazell, Publicity Section; Bernard McGee; Beverley Webb, Information Officer; and all the gardeners we have met during cemetery visits; Mr. Trevor Craker; Mr. Roger Custance, Archivist, Winchester College; Mr. C. Dean, Archivist, St Paul’s School; The Reverend Charles de Candole; Mrs. Audrey de Candole; Mrs. M.E. Griffiths, Archivist and Librarian, Sedbergh School; the staff of the Guildhall Library Aldermanbury, London; Anne Harvey; Mrs. Elspeth Harvey, Librarian Haileybury College; Mr. Daniel Huws, The National Library of Wales; the staff of the Imperial War Museum, particularly from the Printed Books and Documents Departments; Mr. Michael Meredith, Eton College; Mrs. Ann Morris, Trawsfynydd; Mrs. Enid Morris, Trawsfynydd; Major John Porter-Wright; the staff of the Public Records Office, Kew; Brigadier Norman Routledge; the late Viscount St. Davids; Mr. George Simons; Lt. Col. R.J.M. Sinnett; Mr. Andrew Stanley; The Venerable Michael Till, Archdeacon of Canterbury; Mr. Brian Turner; Mr. D.R.C. West, Hon. Archivist, Marlborough College; Mr. Ellis Williams, Trawsfynydd; Dr. Jean Moorcroft Wilson and Mr. Cecil Woolf.

I am also very grateful to the following Archivists, Curators and Regimental Secretaries for providing helpful information:

Colonel (Rtd.) The Hon. W.D. Arbuthnott, MBE, The Black Watch (Royal Highland Regiment); Colonel J.R. Baker (Rtd.), The Royal Green Jackets; Brigadier J.K. Chater, The Royal Regiment of Fusiliers; Major (Rtd.) R.A. Creamer, The Worcestershire and Sherwood Foresters Regiment; Brigadier (Rtd.) J.M. Cubiss, CBE, MC, The Prince of Wales’s Own Regiment of Yorkshire; Lieutenant Colonel (Rtd.) A.A. Fairrie, Queen’s Own Highlanders (Seaforth and Camerons); Colonel J.W. Francis, The Queen’s Regiment; Lieutenant Colonel (Rtd.) A.M. Gabb, OBE, The Worcestershire and Sherwood Foresters Regiment; Major (Rtd.) J. McQ. Hallam, The Royal Regiment of Fusiliers (Lancashire); Captain (Rtd.) C. Harrison, The Gordon Highlanders; Mr. Ian Hook, Keeper of the Essex Regiment Museum; Major A.W. Kersting, Household Cavalry Museum; Mr. R.D. Lippiatt, Secretary, Machine Gun Corps Old Comrades Association; Colonel I.H. McCausland (Rtd.), The Royal Green Jackets; Major R.D.W. McLean, The Staffordshire Regiment; Lieutenant Colonel R.K. May, FMA, Border Regiment and The King’s Own Royal Border Regiment; Major (Rtd.) N.J. Perkins, The Queen’s Lancashire Regiment; Major (Rtd.) J.H. Peters, MBE, The Duke of Edinburgh’s Royal Regiment (Berkshire and Wiltshire); Lieutenant Colonel W.G. Pettifar, MBE, Royal Regiment of Fusiliers (City of London); Lieutenant Colonel (Rtd.) H.L.T. Radice, MBE, The Gloucestershire Regiment; Mr. John Scott, The York and Lancaster Regiment; Lieutenant Colonel A.W. Scott Elliot, Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders; Captain J.H. Sedgwick, Coldstream Guards; Major W. Shaw, MBE (Rtd.), The Royal Highland Fusiliers; Major H.C.L. Tennent, The Queen’s Regiment; Brigadier K.A. Timbers, The Royal Artillery Institution; Mrs. Jean Tsushima, Honourable Artillery Company; Major (Rtd.) A.E.F. Waldron, MBE, Middlesex Regiment; Lieutenant Colonel D.C.R. Ward, the King’s Own Scottish Borderers; Colonel K.N. Wilkins, OBE, Royal Marines Museum; Lieutenant Colonel J.L. Wilson, DL, Royal Tigers’ Association, The Royal Leicestershire Regiment; Lieutenant J.L. Wilson Smith, OBE, The Royal Scots; Lieutenant Colonel R.G. Woodhouse, DL, Somerset Light Infantry.

I am especially indebted to the following for a variety of reasons; for pointing me in the right direction, for advice, support, and friendship:

Dr. Christopher Dowling, The Imperial War Museum; Christine Lingard, Language and Literature Library, Manchester Central Library; Mr. Alan Martin; Mr. Martin Taylor, The Imperial War Museum; Pam Williams, Arts Language and Literature Birmingham Library Services; and particularly to Catherine Reilly, for her superb Bibliography, which has been a guiding light; and Mr. John Kinnane, for printing my original article, A Slate Rubbed Clean, in the Antiquarian Book Monthly Review in 1986.

My final thanks are to my family without whose cheerfulness, encouragement, understanding and love this book would never have been completed. To my three children for sparing precious time in their already full lives; Jonathan for hours of research at the Public Records Office and for solving problems on the computer; Rupert for tracking down many rare books, and for the very exacting task of proof-reading; Lucinda for tireless work on the computer, proof-reading and for taking on all the publicity side.

I can never thank Jeremy enough for his unwavering commitment to the idea of A Deep Cry from the start; for the work he has undertaken towards its production with never-failing stamina and good humour; and for his infinite patience and loving care which has sustained me throughout.

Every effort has been made to trace copyright holders but we apologise to anyone who inadvertently has not been acknowledged.

We will be most interested to hear from anyone who has additional unpublished or unusual information about any of the soldier-poets.

INTRODUCTION

Not far from the main gates of the Supreme Headquarters Allied Powers Europe (SHAPE) outside Mons in Belgium, a stone monument commemorates the date 22nd August 1914 when at 7.00 a.m. a squadron from the 4th Royal Irish Dragoon Guards fired the opening British shots of the First World War. Almost directly opposite, a bronze plaque on a wall of the Hotel Medicis, records: “the outpost of the 116th Canadian Infantry Battalion stopped at this very point upon the cease-fire on November 11th 1918.” Three miles from here, on land originally given to the Germans to bury their own and the British casualties in August 1914, reputedly the first British soldier and the first officer to be killed, the first man to be awarded the Victoria Cross, and the last British soldier to die before the cease-fire, lie buried in the beautiful St. Symphorien Cemetery.

When we arrived at SHAPE in July 1975, the First World War evoked for me a vague jumble of dates and facts highlighted by the knowledge that my Grandfather, a Boer war hero, had been killed commanding his Battalion during the Battle of the Somme. However, over the next few months, although I was aware that the first and last British actions of this War had taken place near where we lived, I wanted to find out what had happened in the years in between; so playing truant from the ladies’ lunch and coffee morning circuit my initial attempts to digest this catastrophic period were at the Musée de Guerre in Mons. Soon Jeremy and I were visiting local war-scarred places; the railway station at Nimy where Lieutenant Dease and Private Godley, of the 4th Battalion, Royal Fusiliers won their V.C.s; the sector round Obourg station where the 4th Battalion Middlesex Regiment’s courageous fighting earned them a special memorial, erected at St. Symphorien by the Germans, who added the accolade ‘Royal’ to their name.

We gradually explored further afield; Verdun, Vimy, the built up areas round Ypres and Passchendaele, the lovely rolling countryside of the Somme, and became more and more appalled each time. Every visit produced a mixture of emotions – horror, grief, anger; and it did not take our senses long to assimilate not only the sheer magnitude of the maiming and slaughter, but the depth of suffering, in every corner of the world, which followed; the shadows linger today.

One Armistice day, using a copy of the description written in pencil three weeks after his death, we found the remote and peaceful cemetery where my Grandfather is buried. Subsequent pilgrimages followed, always leading to new discoveries. We visited cemeteries and memorials in towns, on the outskirts of villages, beside the main roads and at the end of rough country tracks. We tramped over many miles of battleground; in the Spring the chalk outlines of the trenches were clearly visible on the newly ploughed Somme battlefields. Here, too, we found rolls of barbed wire, rusty bayonets, waterbottles, helmets and quantities of ammunition of all different sizes; unexploded shells, we soon realised, remained a danger. During one picnic on the edge of a small copse with our three children, lunch was disturbed by our twelve year-old daughter saying, “What’s this Daddy?” In one swift movement Jeremy took the unexploded hand grenade from her and disappeared into the trees.

When we returned to SHAPE in January 1982 we explored the battle areas again but this time in more detail with other members of a flourishing military history group; we researched some of the seemingly infinite number of names on the headstones and memorials; they represented every walk of life, irrespective of class, religion or culture; death, the ultimate equaliser, threw together the musician and coalminer, countryman, artisan, schoolteacher, barrowboy, writer, doctor, cobbler, tradesman, artist and barrister; they all had a story, and their civilian lives, or acts of courage on the field of battle, gave a new substance to the impersonal row upon countless row of rank and name.

Many survived the fighting but only a few were not physically or emotionally wounded. Over 80 years later there are still a number of surviving veterans, many of whom are cared for by organisations such as the Royal British Legion. In August 1982, thirty-five ‘Old Contemptibles’, the majority of whom had served in the Middlesex Regiment, returned to SHAPE for the annual Battle of Mons ceremonies. The wreath at the stone memorial was laid one morning by a Chelsea Pensioner who had been next to the man who fired the first shot of the war sixty-eight years previously. In the afternoon a joint German and British Service of Reconciliation was held at St. Symphorien Cemetery. The youngest among these veterans was 85 years old and the oldest almost 92. Straight-backed, sprightly and enthusiastic they recalled a rich assortment of harrowing and humorous anecdotes. On their last evening with us, singing ‘It’s a long way to Tipperary’, all the emotion and pride rekindled by a week of pilgrimage and memories, overflowed in song and tears unashamedly.

By this time I was fascinated by the First World War literature; from the biographical details in Brian Gardner’s anthology, Up the Line to Death, I realised that nineteen poets were buried in Northern France. The first of many requests to the Commonwealth War Graves Commission produced a list of the cemeteries where these men lie. During the next two years we visited all these poets, discovered many more and continued to walk over the ground on which they fought and died.

One very cold February afternoon Jeremy and I stood with three friends somewhere in No Man’s Land at Newfoundland Park, Beaumont Hamel. We were examining a map and I was on the edge of the group. I suddenly became conscious of someone standing very still beside me. When I turned to speak there was no one there but the spiritual presence remained for some seconds. As it faded I was filled with a great sense of urgency – as if I had just been told something of vital importance – and must act on it immediately. It has taken me fifteen years to do so.

* * * * *

Over the last fifteen years I have researched the lives of more than eighty British soldier-poets for this book. My touchstone was that each one must have had a volume of war verse published, or to have appeared in an anthology, and that they all died on the Western Front. In the end twenty have been omitted because of scant information. Even so the biographical details for the sixty-six men included are uneven, although schools, families and various books have provided a range of information. Military details vary also. Regimental Histories produced a good over-all picture of particular events; in some cases Battalion Diaries proved comprehensive but in others facts were recorded sketchily – dependent on where and under what circumstances the Diaries were completed. Certain Battalion Diaries are untraceable.

A Deep Cry has been planned as a Literary Pilgrimage. Although the men are grouped chronologically under the year in which they died, 1915; 1916; 1917 and 1918, they are linked geographically on the maps, according to the location of their graves and memorials. In one instance two men who fell during the same battle, serving in the same Battalion, were buried miles apart; in other cases the graves of two soldier-poets will be found in the same cemetery although they were killed in different years. The men who have no known graves and are remembered on the Memorials to the Missing also span the four war years.

The reason for this paradox is that the cemeteries have been created and re-created over many years. Many of the dead still lie in their original graves dug by their comrades after an action; in Base Hospital cemeteries far behind the front line; and in cemeteries near the Main Dressing Stations and Casualty Clearing Stations where they died of wounds. In 1914, Fabian Ware, and his Red Cross unit, began to locate and record these crude graves. His register was recognised by the authorities, and in 1917 the Imperial War Graves Commission was established. At Ware’s request Sir Edwin Lutyens went to France and realised that the graveyards were ‘haphazard from the needs of much to do and little time for thought…’

After the War many thousands of the dead, some still unburied, some taken from original burial grounds and scattered graves, were reburied in cemeteries planned by the War Graves Commission. The Commission, in the face of much opposition, insisted that there should be no distinction between the graves of officers and men and that each headstone must be of identical design.

Over half a million Commonwealth and Foreign dead are buried in over 2,000 Commonwealth War Graves Commission cemeteries in Northern France and Belgium; on the Commission’s twenty-six Memorials to the Missing in this region over 300,000 names are commemorated. The beautiful Cross of Sacrifice overlooks the rows of white headstones; the Stone of Remembrance, symbolising an Altar of Sacrifice, stands in a separate corner. At the gates of each cemetery, a Register gives short historical details of the men buried there.

Sir Edwin Lutyens believed there was ‘no need for the cemeteries to be gloomy or even sad looking places. Good use should be made of the best and most beautiful flowering plants and shrubs…’ Today, these lovely gardens of rest, even those on the edge of housing estates or close to motorways, radiate a sense of infinite peace. A wide variety of magnificent trees are grouped according to the size and shape of the cemetery; there are grassed paths between the rows of graves; the earth in front of the headstones is planted with shrubs, planned for every season of the year, spring bulbs and English cottage garden flowers. There is a profusion of colour and scent during the summer months and warm rich shades in the autumn. 460 Commission gardeners care for this ‘mass multitude of silent witnesses’ on the Western Front all the year round.

Almost 12,000 Commonwealth soldiers, the greatest number to be buried in any War Graves Commission cemetery, lie at Tyne Cot between Passchendaele and Zonnebeke in Belgium; here also, nearly 35,000 names are recorded on the Memorial to the Missing. The Cross of Sacrifice, commanding a view across what was once the Ypres Salient battleground of mud and massacre, was built on a large German blockhouse; behind the Cross, original graves remain as they were found at the end of the War. In Ypres, six miles away, over 54,000 names are inscribed on the vast Menin Gate Memorial to the Missing; every evening traffic is halted here and two buglers sound the Last Post. Apart from the period of the German occupation of Ypres, between May 1940 and September 1944, this short ceremony has continued unbroken since 11th November 1929.

In one of his Sonnets on death, Charles Hamilton Sorley wrote:

“… But now in every road on every side

We see your straight and steadfast signpost there…”

In Northern France these signs read like chapter headings from a children’s storybook. ‘Hawthorn Ridge’; ‘Flat Iron Copse’; ‘Caterpillar Valley’; ‘Cuckoo Passage’; ‘Pigeon Ravine’; ‘Thistle Dump’; all are cemeteries. The great Thiepval Memorial to the Missing, commemorating over 72,000 British and Commonwealth soldiers who died during the Somme battles between July 1915 and March 1918 dominates the cemetery-strewn countryside for many miles. Not far from here a complete trench system has been well preserved at Newfoundland Memorial Park which stands in over 80 acres of land over which many bitter actions were fought.

The soldier-poets in this book are buried in thirty-nine cemeteries and are remembered on seven memorials; all but five lie within forty-five miles of Arras. The oldest to be killed was forty-two and the youngest just nineteen years of age; their military ranks at the time of death, spanned from private soldier to a twenty-three year old volunteer, who enlisted in August 1914, and, after gaining his commission, was promoted from Lieutenant to Lieutenant-Colonel in thirteen months. Seven were killed on the 1st July 1916, the first day of the Battle of the Somme. At all the hallowed places where they lie there are many poignant examples of the ‘carnage incomprehensible’ of the four tragic war years; a headstone of a member of the Chinese Labour Corps, who died far from home, inscribed with his number, date of death and the words ‘A Good Reputation Endures Forever’; the sombre gravestones of a group of German soldiers remind that ‘victor and vanquished are a-one in death’ and that those who fought against each other often share the same resting ground; and the magnificent tree, white with blossom in the spring and laden with cherries in June, standing at the entrance to Agny Military Cemetery where Edward Thomas lies, immortalises his quatrain, a lament for all the sorrow and desolation of war.

* * * * *

It is difficult to appreciate, more than 80 years later, that the majority of the population in Great Britain were unaware of the true conditions and scale of the First World War. Until the casualty lists permeated the newspapers, few people at home realised the horror of what was happening across the Channel. There was neither radio nor television, and telephones were not in general use. Although telegrams were occasionally sent, letter writing was the principal means of communication for the fighting man. For the most part it was a quick way of maintaining contact; for those who were either wounded, illiterate, or had neither time nor inclination, there were official postcards, with printed headings against which a man could indicate his state of health etc. It was forbidden to keep a private diary at the Front, so these were written in secret and kept hidden. A vast amount of poems and rhymes were composed, sent home and printed in the daily newspapers and magazines and published in book form.

From the trenches, behind the lines, in hospitals and on leave, the soldier-poets wrote of the carnage, suffering and grim conditions they experienced. Some of these writers, who have become well-known, produced literature which will endure for ever; the lesser known may also influence and enhance our appreciation of war. The crude verse and impulsive description, written shortly before or after a terrible bombardment, are as important to understanding a soldier’s feelings at that time as any of the finer poems and articulate prose.

The often hastily pencil-scribbled poems, letters and diaries cover a wide range of outlook and response to the brutal world of war. Every human emotion was shared and is evoked in unique language: vivid imagery, candid observation, lucid narrative, forceful accounts, straightforward comments and simple impressions. The philosopher, the underprivileged, the dreamer and the intellectual, expressed anger, fear, hope, humour, compassion, boredom, homesickness and despair in his own inimitable style. Common to each man was nostalgia for the way of life he once knew, love of his family, revulsion of violence, and anticipation of death.

The perceptive soon realised the futility of war. They were cynical and critical of both Government policy and the military chaos around them. Officers acknowledged the difference between the relative comfort they enjoyed behind the lines compared to the conditions their soldiers were subjected to. The trenches were cruel and dangerous, mud-thick, rat-infested, places of filth and foreboding for all ranks. Hence out of brutality and bloodshed was born an extra-ordinary camaraderie; pain and fear and death bred sympathy, and tolerance towards comrades and the enemy.

Almost every Christian and Jewish soldier-poet struggled with the insoluble question as to where his God stood in the nightmare inferno of battle. The poems, letters and diaries constantly reveal the attempt to keep at least some form of belief in the sanctity of life and an all encompassing Goodness, in the scenario of hellfire and agony. Many men remained deeply committed to their religion, displaying absolute trust and an unshakeable conviction of their immortality; some one-time believers were driven to doubt and disillusionment; a few lost their faith completely.

A few miles behind the front, day-to-day life in France continued almost unchanged and the countryside remained undamaged, but the ground over which the battles were fought was devastated. Towns and villages lay in shattered ruins, trees were uprooted, fields and roads became a quagmire of mud, scarred with deep craters and shell-holes, the great desolation littered with mangled corpses. Nature, on the other hand, remained unaffected by all this; wild flowers grew on wasteland and wayside, larks flew and sang overhead. Bitter cold, torrential rain and intense heat caused endless discomfort; nevertheless the seasons could still provide occasional solace to the weary soldier when he found an isolated copse with the promise of green shoots and blossom, flowers amd soft fruit in a garden which had miraculously escaped destruction. A constant theme in the poetry and prose is the comparison between the very least of nature’s wonders and man’s relentless madness and destruction.

The soldier-poets came from many different backgrounds; from the working-class to the aristocratic. Only a small proportion were regular soldiers, working or professional men; the majority joined the Army straight from their public schools where the competitive spirit was all important. A few of these young men had a mature outlook from the start of the war and realised there would be neither glory nor splendour in the conflict ahead; others saw the challenge of the games field continued on the field of battle. This jingoistic fervour was crushed in the grim reality of actual warfare. A handful of the writers were virtually self-educated having left the local board school at the age of fourteen; the long working hours which followed made further education difficult, but they persevered in their few hours of leisure and ultimately produced some of the most remarkable writing of the war.

These sixty-six soldier-poets, remembered in grave-gardens over the Western Front, fought alongside and against a multitude of men. They represent the millions of combatants on the conflicting sides. Their underlying message of hope for reconciliation, tolerance and peace went unheeded. Their testimony of man’s inhumanity to one another remains as clear and chilling in today’s troubled world as it was then.

Anne Powell

Aberporth

1998

THE SOLDIER-POETS IN CHRONOLOGICAL ORDER OF THEIR DEATH

Name and Rank

Regiment/Unit

Date of Death

Cemetery/Memorial

Page

1915

STERLING

1st Royal Scots Fusiliers

23 April

Dickebusch

2–5

Lt., R.W.

New Military

Cemetery

LYON

9th Royal Scots

8 May

Menin Gate

6–9

Lt., W.S.S.

Memorial

PHILIPPS

Royal Horse Guards

13 May

Menin Gate

10–14

Capt. The Hon., C.E.A.

Memorial

GRENFELL

1st Royal Dragoons

26 May

Boulogne

15–27

Capt The Hon., J.H.F., DSO

Eastern

Cemetery

SORLEY

7th Suffolk Regiment

13 October

Loos Memorial

28–39

Capt., C.H.

LEIGHTON

1st/7th Worcestershire

23 December

Louvencourt

40–45

Lt., R.A.

Regiment

Military

Cemetery

1916

FRESTON

6th Royal Berkshire

24 January

Bécourt

48–52

2nd Lt., H.R.

Regiment

Military

Cemetery

HORNE

7th Kings Own Scottish

27 January

Mazingarbe

53–57

Capt., C.M.

Borderers

Communal

Cemetery

PITT

10th Border Regiment

30 April

Arras Memorial

58–68

2nd Lt., B.

(Attached 47th Trench Mortar Battery)

STREETS

12th York and Lancaster

1 July

Euston Road

69–74

Sgt., J.W.

Regiment

Cemetery

ROBERTSON

12th York and Lancaster

1 July

Thiepval

75–80

Cpl., A.

Regiment

Memorial

WATERHOUSE

2nd Essex Regiment

1 July

Serre Road

81–86

2nd Lt., G.

Cemetery No 2

FIELD

6th Royal Warwickshire

1 July

Serre Road

87–89

2nd Lt., H.L.

Regiment

Cemetery No 2

WHITE

20th Northumberland

1 July

Thiepval

90–95

Lt., B.C. de B.

Fusiliers (Tyneside Scottish)

Memorial

RATCLIFFE

10th West Yorkshire

1 July

Fricourt New

96–97

Lt., A.V.

Regiment

Military

Cemetery

HODGSON

9th Devonshire Regiment

1 July

Devonshire

98–105

Lt., W.N., MC

Cemetery,

Mansel Copse

JOHNSON

2nd Manchester Regiment

15 July

Bouzincourt

106–109

Lt., D.F.G.

Communal

Cemetery

DENNYS

10th Loyal North

24 July

St Sever

110–114

Capt., R.M.

Lancashire Regiment

Cemetery,

Rouen

BECKH

12th East Yorkshire

15 August

Cabaret-Rouge

115–117

2nd Lt., R.H.

Regiment

British

Cemetery

SMITH

2nd Argyll and Sutherland

18 August

Caterpillar

118–120

Capt., H.S.

Highlanders

Valley

Cemetery

BERRIDGE

6th Somerset Light

20 August

Heilly

121–125

2nd Lt., W.E.

Infantry

Station

Cemetery

WINTERBOTHAM

1st/5th Gloucesteshire

27 August

Thiepval

126–129

Lt., C.W.

Regiment

Memorial

KETTLE

9th Royal Dublin Fusiliers

9 September

Thiepval

130–139

Lt., T.M.

Memorial

ASQUITH

3rd Grenadier Guards

15 September

Guillemont

140–151

Lt., R.

Road

Cemetery

TENNANT

4th Grenadier Guards

22 September

Guillemont

152–164

Lt., The Hon., E.W.

Road

Cemetery

TODD

1st/12th London Regiment

7 October

Thiepval

165–168

Rflmn., N.H.

(The Rangers)

Memorial

COULSON

12th London Regiment

8 October

Grove Town

169–173

Sgt., F.L.A.

(The Rangers)

Cemetery

SMITH

19th Lancashire Fusiliers

3 December

Warlincourt

174–175

Lt., G.B.

Halte British

Cemetery

1917

GRAY

2nd Royal Berkshire

4 March

Sailly-Saillisel

178–182

2nd Lt., J.A., DCM

Regiment

British

Cemetery

WEST

6th Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire Light

3 April

HAC Cemetery, Ecoust-St. Mein

183–196

Capt., A.G.

WILKINSON

1st/8th Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders

9 April

Highland

197–199

2nd Lt., W.L.

Cemetery

Roclincourt

THOMAS

244th Siege Battery, Royal

9 April

Agny Military

200–214

2nd Lt., P.E.

Garrison Artillery

Cemetery

VERNEDE

12th Rifle Brigade

9 April

Lebucquière

215–227

2nd Lt., R.E.

Communal

Cemetery

MANN

8th Black Watch

10 April

Aubigny

228–230

2nd Lt., A.J.

Communal

Cemetery

LITTLEJOHN

1st/7th Middlesex

10 April

Wancourt

231–232

C.S.M., W.H.

Regiment

British

Cemetery

FLOWER

242nd Brigade,

20 April

Arras

233–236

Driver, C.

Royal Field Artillery

Memorial

CROMBIE

4th Gordon Highlanders

23 April

Duisans

237–241

Capt., J.E.

British

Cemetery

MORRIS

No. 3 Squadron

29 April

St. Sever

242–243

2nd Lt., F. St. V.

Royal Flying Corps

Cemetery

Rouen

PARRY

17th Kings Royal Rifle

6 May

Vlamertinghe

244–248

2nd Lt., H.

Corps

Military

Cemetery

TROTTER

11th Leicestershire

7 May

Mazingarbe

249–253

2nd Lt., B.F.

Regiment

Communal

Cemetery

DOWN

4th Royal Berkshire

22 May

Hermies Hill

254–256

Capt., W.O., MC

Regiment

British

Cemetery

SAMUEL

10th Royal West Kent

7 June

Menin Gate

257–259

Lt., G.G.

Regiment

Memorial

SHORT

286th Brigade, Royal

21 June

Cité Bonjean

260–263

Lt-Col., W.A.

Field Artillery

Military

Cemetery

MASEFIELD

1st/5th North

2 July

Cabaret-Rouge

264–269

Capt., C.J.B., MC

Staffordshire Regiment

British

Cemetery

HOBSON

116th Company, Machine

31 July

Menin Gate

270–275

Lt., J.C.

Gun Corps

Memorial

EVANS

15th Royal Welch

31 July

Artillery Wood

276–279

Pte., E.H.

Fusiliers

Cemetery

Boesinghe

LEDWIDGE

1st Royal Inniskilling

31 July

Artillery Wood

280–289

L/Cpl., F.

Fusiliers

Cemetery,

Boesinghe

HULME

Naval Siege Battery,

28 September

Coxyde

290–303

Lt., T.E.

Royal Marine Artillery

Military

Cemetery

WILKINSON

8th West Yorkshire

9 October

Tyne Cot

304–309

Capt., E.F., MC

Regiment

Memorial

HAMILTON

Coldstream Guards

12 October

Tyne Cot

310–311

2nd Lt., W.R.

(Attached 4th Guards Machine Gun Regiment)

Memorial

MACKINTOSH

4th Seaforth

21 November

Orival Wood

312–321

Lt., E.A., MC

Highlanders

Cemetery

SHAW-STEWART

Hood Battalion, Royal

30 December

Metz-en-Couture

322–330

Lt-Cdr., P.H. RNVR., Chevalier of the Legion of Honour; Croix de Guerre

Naval Division

Communal

Cemetery

1918

MITCHELL

3rd Rifle Brigade

22 March

Pozières

332–335

Rflmn., C.

Memorial

WILSON

10th Sherwood Foresters

23 March

Arras

336–344

Capt., T.P.C.

Memorial

BLACKALL

4th South Staffordshire

25 March

Arras

345–349

Lt-Col., C.W.

Regiment

Memorial

ROSENBERG

1st Kings Own Royal

1 April

Bailleul Road

350–361

Pte., I.

Lancaster Regiment

East Cemetery

BROWN

9th Seaforth Highlanders

11 April

Voormezeele

362–371

Lt., J., MC

Enclosure No 3

STEWART

4th South Staffordshire

26 April

Tyne Cot

372–377

Lt-Col., J.E., MC

Regiment

Memorial

TEMPLER

1st Gloucestershire

4 June

Loos Memorial

378–382

Capt., C.F.L.

Regiment

PENROSE

245th Siege Battery,

1 August

Esquelbecq

383–388

Maj., C.Q.L.,

Royal Garrison

Military

MC & Bar

Artillery

Cemetery

BAKER

7th London Regiment

8 August

Vis-en-Artois

389–392

Pte., J.S.M.

Memorial

HARDYMAN

8th Somerset Light

24 August

Bienvillers

393–398

Lt-Col., J.H.M.,

Infantry

Military

DSO, MC

Cemetery

SIMPSON

1st Lancashire

29 August

Vis-en-Artois

399–402

2nd Lt., H.L.

Fusiliers

Memorial

de CANDOLE

4th Wiltshire Regiment (Attached 49th Company, Machine Gun Corps)

3 September

Aubigny

403–406

Lt., A.C.V.

Communal

Cemetery

PEMBERTON

216th Siege Battery,

7 October

Bellicourt

407–410

Capt., V.T., MC

Royal Garrison

British

Artillery

Cemetery

OWEN

2nd Manchester Regiment

4 November

Ors Village

411–428

Lt., W.E.S., MC

Communal

Cemetery

1915

LIEUTENANT ROBERT WILLIAM STERLING

1st Battalion Royal Scots Fusiliers.

Born: 19 November 1893. Glasgow.

Educated: Glasgow Academy

Sedbergh School.

Pembroke College, Oxford.

Killed: 23rd April 1915. Aged 22 years.

Dickebusch New Military Cemetery, Belgium.

Robert Sterling gained a Classical Scholarship to Pembroke College, Oxford in 1912, and two years later won the Newdigate Prize with his poem ‘The Burial of Sophocles’. Shortly afterwards War was declared and his career at Oxford ended. His love for Oxford is reflected in six out of the nine poems he wrote between 1913 and 1915 praising the University and his College:

TO PEMBROKE COLLEGE

Full often, with a cloud about me shed

Of phantoms numberless, I have alone

Wander’d in Ancient Oxford marvelling:

Calling the storied stone to yield its dead:

And I have seen the sunlight richly thrown

On spire and patient turret, conjuring

Old glass to marled beauty with its kiss,

And making blossom all the foison sown

Through lapsed years. I’ve felt the deeper bliss

Of eve calm-brooding o’er her loved care,

And tingeing her one all-embosoming tone.

And I have dream’d on thee, thou college fair,

Dearest to me of all, until I seem’d

Sunk in the very substance that I dream’d.

And oh! methought that this whole edifice,

Forg’d in the spirit and the fires that burn

Out of that past of splendent histories,

Up-towering yet, fresh potency might learn,

And to new summits turn,

Vaunting the banner still of what hath been and is.

Sterling was commissioned in the Royal Scots Fusiliers and sent to Scotland for training. He arrived in the Ypres area in February 1915 and the Battalion was in and out of trenches at St. Eloi. A few weeks later a close friend arrived unexpectedly at the billets at Reninghelst. Sterling wrote:

As always we didn’t know who was going to relieve us, and we were sitting in our quarters – what remained of the shell-shattered lodge of the chateau, playing cards by candle-light, awaiting events…

The two friends walked for an hour and a half in the chateau grounds with stray bullets from the firing-line whistling around them. Ten days later his friend was killed and Sterling recalled their last meeting:

I had no idea I was afterwards going to treasure every incident as a precious memory all my life. I think I should go mad, if I didn’t still cherish some faith in the justice of things, and a vague but confident belief that death cannot end great friendships.

LINES WRITTEN IN THE TRENCHES

I

Ah! Hate like this would freeze our human tears,

And stab the morning star:

Not it, not it commands and mourns and bears

The storm and bitter glory of red war.

II

To J.H.S.M., killed in action, March 13th, 1915.

O Brother, I have sung no dirge for thee:

Nor for all time to come

Can song reveal my grief’s infinity:

The menace of thy silence made me dumb.

After six weeks at the front Sterling wrote:

I have had a comparatively easy time of it so far. My worst experience was a half hour’s shelling when the enemy’s artillery caught me with a platoon of men digging a trench in the open. On another occasion one of our trenches was blown up by a mine and lost us 60 men, but the Germans who attempted an attack at the time were quickly repulsed, and hardly any of them got back alive to their own trench.

THE ROUND

Crown of the morning

Laid on the toiler:

Joy to the heart

Hope-rich.

Treasure behind left;

Riches before him,

Treasur’d in toil,

To glean.

Starlit and hushful

Wearily homeward:

Rest to the brow

Toil-stain’d.

At the beginning of April 1915, Sterling was sent to hospital at Ypres suffering from influenza; this hospital and the subsequent one at Poperinghe, were shelled and he was sent on to Le Tréport.

The Second Battle of Ypres started on 14th April, 1915 and the town was completely destroyed during the German bombardment which continued for almost a month. Sterling rejoined his battalion and wrote to a friend on 18th April:

… I’ve been longing for some link with the normal universe detached from the storm. It is funny how trivial instances sometimes are seized as symbols by the memory; but I did find such a link about three weeks ago. We were in trenches in woody country (just S.E. of Ypres). The Germans were about eighty yards away, and between the trenches lay pitiful heaps of dead friends and foes. Such trees as were left standing were little more than stumps, both behind our lines and the enemy’s. The enemy had just been shelling our reserve trenches, and a Belgian Battery behind us had been replying, when there fell a few minutes’ silence; and I, still crouching expectantly in the trench, suddenly saw a pair of thrushes building a nest in a “bare ruin’d choir” of a tree, only about five yards behind our line. At the same time a lark began to sing in the sky above the German trenches. It seemed almost incredible at the time, but now, whenever I think of those nest-builders and that all but “sightless song”, they seem to represent in some degree the very essence of the Normal and Unchangeable Universe carrying on unhindered and careless amid the corpses and the bullets and the madness…

In his History of the Royal Scots Fusiliers, John Buchan wrote of what happened to the 1st Battalion who had been in the Ypres Salient with the 28th Division “suffering much from mines and shellfire and mud:”

On 20th April the Division held the front from north-east of Zonnebeke to the Polygon Wood, with the Canadians on its left and the Twenty-seventh Division on its right. On the 17th, Hill 60, at the southern re-entrant of the salient, had been taken and held, and on the 20th there began a bombardment of the town of Ypres with heavy shells, which seemed to augur an enemy advance. On the night of the 22nd, in pleasant spring weather, the Germans launched the first gas attack in the campaign, which forced the French behind the canal and made a formidable breach in the Allied line. Then followed the heroic stand of the Canadians, who stopped the breach, the fight of ‘Geddes’s Detachment’, the shortening of the British line, and the long-drawn torture of the three weeks’ action which we call the Second Battle of Ypres. The front of the Twenty-eighth Division was not the centre of the fiercest fighting, and the 1st Royal Scots Fusiliers were not engaged in any of the greatest episodes. But till the battle died away in early June they had their share of losses. On 22nd April Second Lieutenant Wallner was killed in an attack on their trenches, and next day Second Lieutenant R.W. Sterling, a young officer of notable promise, fell, after holding a length of trench all day with 15 men…

LIEUTENANT WALTER SCOTT STUART LYON

9th Battalion Royal Scots.

Born: 1st October 1886. North Berwick.

Educated: Haileybury College.

Balliol College, Oxford.

Killed: 8th May 1915. Aged 28 years.

Menin Gate Memorial to the Missing, Ypres, Belgium.

Walter Lyon graduated in Law at Edinburgh University in 1912 and became an advocate. The Balliol College War Memorial Book records that:

… he was extremely silent and reserved, and probably suffered a good deal from solitude… He is said to have been the first member of the Scottish Bar to fall in the war, and even the first advocate to fall in action since Flodden Field…

Lyon joined the Royal Scots before the War. He arrived in Belgium with the Battalion at the end of February 1915; after a few weeks behind the lines at L’Abeele and Dickebusch he went to trenches in Glencorse Wood, Westhoek near Ypres. On 9th, 10th and 11th April Lyon wrote two poems from ‘Mon Privilège’, his dug-out:

EASTER AT YPRES: 1915

The sacred Head was bound and diapered,

The sacred Body wrapped in charnel shroud,

And hearts were breaking, hopes that towered were bowed,

And life died quite when died the living Word.

So lies this ruined city. She hath heard

The rush of foes brutal and strong and proud,

And felt their bolted fury. She is ploughed

With fire and steel, and all her grace is blurred.

But with the third sun rose the Light indeed,

Calm and victorious though with brows yet marred

By Hell’s red flame so lately visited.

Nor less for thee, sweet city, better starred

Than this grim hour portends, new times succeed;

And thou shalt reawake, though aye be scarred.

LINES WRITTEN IN A FIRE TRENCH

‘Tis midnight, and above the hollow trench

Seen through a gaunt wood’s battle-blasted trunks

And the stark rafters of a shattered grange,

The quiet sky hangs huge and thick with stars.

And through the vast gloom, murdering its peace,

Guns bellow and their shells rush swishing ere

They burst in death and thunder, or they fling

Wild jangling spirals round the screaming air.

Bullets whine by, and maxims drub like drums,

And through the heaped confusion of all sounds

One great gun drives its single vibrant “Broum.”

And scarce five score of paces from the wall

Of piled sand-bags and barb-toothed nets of wire

(So near and yet what thousand leagues away)

The unseen foe both adds and listens to

The selfsame discord, eyed by the same stars.

Deep darkness hides the desolated land,

Save where a sudden flare sails up and bursts

In whitest glare above the wilderness,

And for one instant lights with lurid pallor

The tense, packed faces in the black redoubt.

In the early hours of the morning of 16th April 1915, during the Second Battle of Ypres, Lyon wrote ‘On a Grave in a Trench inscribed “English killed for the Patrie”’, and a few days later from the trenches in Glencorse Wood he wrote ‘I tracked a dead man down a trench’.

ON A GRAVE IN A TRENCH INSCRIBED “ENGLISH KILLED FOR THE PATRIE”

You fell on Belgian land,

And by a Frenchman’s hand

Were buried. Now your fate

A kinsman doth relate.

Three names meet in this trench:

Belgian, English, French;

Three names, but one the fight

For Freedom, Law and Light.

And you in that crusade

Alive were my comrade

And theirs, the dead whose names

Shine like immortal flames.

And though unnamed you be,

Oh “Killed for the Patrie”,

In honour’s lap you lie

Sealed of their company.

I TRACKED A DEAD MAN DOWN A TRENCH

I tracked a dead man down a trench,

I knew not he was dead.

They told me he had gone that way,

And there his foot-marks led.

The trench was long and close and curved,

It seemed without an end;

And as I threaded each new bay

I thought to see my friend.

I went there stooping to the ground.

For, should I raise my head,

Death watched to spring; and how should then

A dead man find the dead?

At last I saw his back. He crouched

As still as still could be,

And when I called his name aloud

He did not answer me.

The floor-way of the trench was wet

Where he was crouching dead;

The water of the pool was brown,

And round him it was red.

I stole up softly where he stayed

With head hung down all slack,

And on his shoulders laid my hands

And drew him gently back.

And then, as I had guessed, I saw

His head, and how the crown –

I saw then why he crouched so still,

And why his head hung down.

At the beginning of May 1915 the 9th Battalion Royal Scots was alternately in trenches near Potijze Wood, south of the Menin Road, and in dug-outs only 200 yards from the firing-line inside the Wood. The History of The Royal Scots records:

… on the 8th May the heaviest bombardment we had ever experienced broke out… The shelling was terrific; from early morning till dark high explosives and shrapnel rained through the wood. Fine old trees fell torn to the roots by a coal-box; tops of others were sliced by shrapnel, and their new year’s greenery died early: the whole wood became a scene of tragic devastation. Far worse than that, the stream of wounded became uninterrupted. We ourselves lost our first officer killed – Lieutenant Lyon…

CAPTAIN THE HONOURABLE COLWYN ERASMUS ARNOLD PHILIPPS

Royal Horse Guards.

Born: 11th December 1888. London.

Educated: Eton College.

Killed: 13th May 1915. Aged 26 years.

Menin Gate Memorial to the Missing, Ypres, Belgium.

Colwyn Philipps was the eldest son of Lord and Lady St. Davids. He was commissioned in the Royal Horse Guards in October 1908. Most of his light verse was written before the War.

Philipps arrived in billets at Verlorenhoek, in the Ypres Salient, on 4th November 1914; the Battalion was in support trenches at Hooge and Zwarte-Leen and then in the front line. In a letter home dated 10th November, Philipps wrote an account of his ‘first battle’:

… We were ordered to relieve some troops in the advanced trench. We rode about six miles, then dismounted, leaving some men with the horses, and walked about five miles to the trenches. As we went through the first village, we got heavily shelled by the famous Black Marias; they make a noise just like an express train and burst like a clap of thunder, you hear them coming for ten seconds before they burst. It was very unpleasant, and you need to keep a hold on yourself to prevent ducking – most of the men duck.

Most of the shells hit the roofs, but one burst in the road in front of me, killing one man and wounding four or five. However, once we got out of the village they stopped, and we arrived at the trenches in the dark of the evening. We filed quietly into them and waited in the darkness. We stayed there two days and nights, being shelled most of the time. The German trenches were about 1600 yards away, with Maxim guns. They never showed their noses by daylight, and the guns were miles away. We never fired a shot all the time. They only once hit the trench, wounding two men, but about fifty shells pitched within a few yards. They set fire to a large farm a hundred yards behind us that made a glorious blaze. The Frenchmen on our right and left kept up intermittent bursts of rifle-fire. This did no good and gave away the position of their trenches, so they got more shelled than we did. We have now come out and are billeted in a farm ten miles behind the trenches. We had dozens of guns behind our trenches, but they seemed to have little or no effect on keeping down the German fire. Now about tips. – Dig, never mind if the men are tired, always dig. Make trenches as narrow as possible, with no parapet if possible; dig them in groups of eight or ten men, and join up later, leave large traverses. Once you have got your deep narrow trench you can widen out the bottom, but don’t hollow out too much, as a Maria shakes the ground for a hundred yards and will make the whole thing fall in. Don’t allow any movement or heads to show, or any digging or going to the rear in the daytime. All that can be done at night or in the mists of morning that are heavy and last till 8 or 9 a.m. Always carry wire and always put wire forty yards in front of the trench, not more. One trip wire will do if you have no time for more. The Germans often rush at night and the knowledge of wire gives the men confidence. Don’t shoot unless you have a first-rate target, and don’t ever shoot from the trenches at aeroplanes – remember that the whole thing is concealment, and then again concealment. Never give the order ‘fire’ without stating the number of rounds, as otherwise you will never stop them again; you can’t be too strict about this in training. On the whole I don’t think gun-fire is alarming, but from what I see of others it has an awfully wearing effect on the nerves after a time…

Philipps had leave in England in December 1914 and in February 1915. After he rejoined the Battalion in the Ypres Salient he wrote on 12th March, to his mother:

People out here seem to think that the war is going to be quite short, why, I don’t know; personally, I see nothing here to prevent it going on for ever. We never attack the Germans, and simply do our utmost to maintain ourselves; when we seem to advance it is really that the Germans have evacuated the place. Someone once said that war was utter boredom for months interspersed by moments of acute terror – the boredom is a fact… Except for a belt of about twelve miles where the battle is being waged, the whole country shows hardly a sign of war. In many places the inhabitants return the day after the battle… We have had a lot of fighting all in trenches and look like having more… The other day we were evacuating some trenches and the question was if we could cross a piece of much-shelled ground safely – i.e., Was it under direct observation of their gunners? ‘Send on one troop and see’ was the order. I was first, and I saw the men’s faces look rather long. I had no cigarettes, so I took a ration biscuit in one hand and a lump of cheese in the other and retired eating these in alternate mouthfuls to ‘restore confidence’. We escaped without a shell, but I almost choked myself! It looks to me as if we shall have a busy time now…

On 26th April, twelve days after the start of the Second Battle of Ypres, Philipps wrote from Vlamertinghe:

This is a baby letter actually written in battle. Lord knows when it will be posted… I will write to you again when we finish this fight. We have just been moved up in support of the Canadians and may go into the line any time – a whole brigade of us is sitting by the road awaiting orders.

‘Saddle up’ has come – we are off.

On 29th April Philipps was billetted in a farm between L’Abeele and Steenvoorde:

For five days we have been riding round a most hotly contested battle, occasionally taking part – we have only lost half a dozen men and the crisis seems to be over… I am writing this in a farm a few miles back where we are in reserve. It is a most glorious spring evening, the air is heavy with the scent of bursting buds, and a great fat harvest-moon is roosting on the barn. It seems almost impossible to believe that the continuous rumble of distant thunder is caused by those damned guns.

The trooper is a curious animal – he will watch shells bursting 200 yards from him with perfect equanimity as rather adding interest to the view – then one comes really close and he huddles down miserably. Personally a shell within 200 yards impresses me as much as one at my feet. Another amazing and fortunate thing is the shortness of his memory – his best friend dies in agony at his side, and it depresses him for half an hour… The latest joke on the front is to call the cavalry the M.P.s, because they sit and do nothing.

On 12th May the Battalion received orders to take over trenches between the Ypres – Zonnebeke road and the Ypres – Menin road.

Sir John French’s Despatch for the 13th May reported “the heaviest bombardment yet experienced broke out at 4.30 a.m. and continued with little intermission throughout the day.” A Royal Horse Guards Trooper wrote five days later:

The regiment entered the reserve trenches almost on the outskirts of Ypres, on the night of the 12th, relieving the Middlesex Regiment. We proceeded to make ourselves as comfortable as we could, but about half-past two we were all disturbed by the Brigade Major ordering us all to move well along to our right, to allow a returned party of Essex Yeomanry from trench digging to get under cover. After a while we were somehow squeezed into the dug-outs again; it was pouring with rain and about 4 o’clock at the break of day the German Artillery commenced a violent bombardment. We still remained inactive despite the heavy firing. At about 6–8 a.m. (it was so hard to tell the time) we could see our people retiring in small batches from the second line of trenches, and when they reached our trenches we found they were the Life Guards, clean blown from the trenches and dug-outs and without a semblance of cover. After a short while Captain Bowlby, the Squadron Commander, called the Life Guards together, and they got back towards the firing line. All this time Captain Philipps was with us. I was in his troop. He was amusing himself by passing a loaf of stale bread and a tin of meat to Mr. Ward Price, and he told me to send the message that the kidneys were spoilt by cooking too much. He was as usual in the best of spirits and always on the look out. At about 10 o’clock we all made a move to our immediate right, I should think one and a half miles under shrapnel and bullet fire. Passing a large farm we were roughly called together and advanced in single file with a few casualties, then we had to extend again, as shrapnel was getting thick. Finally we reached the dug-outs held by the 1st Royal Dragoons. It was a complete cavalry movement acting as infantry. All this time we were receiving a terrible fire from the artillery. Most of us got into the remnants of the dug-outs, as the trenches in front were completely filled in by Jack Johnsons and were quite flat. At this time I was in conversation with Captain Philipps, who was explaining to me that to our left from 200 to 300 yards of the line was not held. I asked Captain Philipps what he expected to happen if the Germans got to know this, and he replied that he felt sure they knew, but were too chicken-hearted to attack. Just at that moment he was showing me a Catholic medal picked up at Ypres. We suddenly had an order to stand to and he slipped away without the medal.

From this moment commenced the most awful shell fire that God ever has allowed. We were ordered to advance. By clambering over the dug-outs we reached open ground affording excellent targets to the Germans. Captain Philipps inquired where Captain Bowlby was, and I told him I had seen him climb over just previously. Captain Philipps shouted to get over as quickly as possible and follow him. He climbed over and ran a distance of about thirty yards and then spread flat quite unhurt. I ran behind about half the distance. It is really impossible to give you the faintest idea of what was happening; it was as if we were in a terrific hailstorm, only lead instead of hail. Everything had been prepared on their front and we were not prepared. They had their machine-guns simply dealing out for all they were worth, and the artillery had the range beforehand. Seeing Captain Philipps to my front I got up to be as near as I could, knowing it would be a charge in a few seconds. I wanted to get a crowd together to support each other, and besides I had my Colt repeater, which was useless to me, as my rifle took all my time using, and I wanted to give it to Captain Philipps instead of his sword. In the morning he had been inspecting the Colt and told me to get hold of a German officer and pinch his cartridges. Those were his words. However, on rising to rush forward I stopped one – it entered my thigh and passed right through. I dropped on the spot, and as I was dragged into a hedge and down an embankment I saw that our troops had all rushed forward again. This was the last I saw of Captain Philipps, and it was half-past two in the afternoon of the 13th. I crawled back towards Ypres, it taking me seven hours to do about three miles, and eventually I was picked up outside Ypres…

Colwyn Phillips was mentioned in despatches on 1st January 1916. When his kit arrived home his parents found the following poem in his notebook:

There is a healing magic in the night,

The breeze blows cleaner than it did by day,

Forgot the fever of the fuller light,

And sorrow sinks insensibly away

As if some saint a cool white hand did lay

Upon the brow, and calm the restless brain.

The moon looks down with pale unpassioned ray –

Sufficient for the hour is its pain.

Be still and feel the night that hides away earth’s stain.

Be still and loose the sense of God in you,

Be still and send your soul into the all,

The vasty distance where the stars shine blue,

No longer antlike on the earth to crawl.

Released from time and sense of great or small

Float on the pinions of the Night-Queen’s wings;

Soar till the swift inevitable fall

Will drag you back into all the world’s small things;

Yet for an hour be one with all escaped things.

CAPTAIN, THE HONOURABLE JULIAN HENRY FRANCIS GRENFELL, D.S.O.

1st Battalion Royal Dragoons.

Born: 30th March 1888. London.

Educated: Eton College.

Balliol College, Oxford.

Died of Wounds: 26th May 1915. Aged 27 years.

Boulogne Eastern Cemetery, France.