45,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: John Wiley & Sons

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Serie: Blackwell Guides to Classical Literature

- Sprache: Englisch

This newly updated second edition features wide-ranging, systematically organized scholarship in a concise introduction to ancient Greek drama, which flourished from the sixth to third century BC.

- Covers all three genres of ancient Greek drama – tragedy, comedy, and satyr-drama

- Surveys the extant work of Aeschylus, Sophokles, Euripides, Aristophanes, and Menander, and includes entries on ‘lost’ playwrights

- Examines contextual issues such as the origins of dramatic art forms; the conventions of the festivals and the theater; drama’s relationship with the worship of Dionysos; political dimensions of drama; and how to read and watch Greek drama

- Includes single-page synopses of every surviving ancient Greek play

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 823

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Ähnliche

Table of Contents

Praise for A Guide to Ancient Greek Drama

BLACKWELL GUIDES TO CLASSICAL LITERATURE

Title page

Copyright page

Dedication

Preface to the First Edition

Preface to the Second Edition

List of Figures

List of Maps and Plans

Abbreviations and Signs

Maps

1: Aspects of Ancient Greek Drama

Drama

The Dramatic Festivals

The Theatrical Space

The Performance

Drama, Dionysos, and the Polis

Recommended Reading

2: Greek Tragedy

On the Nature of Greek Tragedy

Aeschylus

Sophokles

Euripides

The Other Tragedians

Recommended Reading

3: The Satyr-Drama

Cyclops

Recommended Reading

4: Greek Comedy

Origins

Old Comedy (486 – ca. 385)

The Generations of Old Comedy

Aristophanes

Greek Comedy and the Phlyax-vases

Middle Comedy

Menander and New Comedy

Recommended Reading

5: Approaching Greek Drama

Formal Criticism

Interdisciplinary Approaches

Visual Interpretations

Reception Studies

Recommended Reading

6: Play Synopses

Aeschylus' Persians (Persae, Persai)

Aeschylus' Seven (Seven against Thebes)

Aeschylus' Suppliants (Suppliant Women, Hiketides)

Aeschylus' Oresteia

Aeschylus' Agamemnon

Aeschylus' Libation-Bearers (Choephoroe)

Aeschylus' Eumenides (Furies)

Aeschylus' Prometheus Bound (Prometheus Vinctus, Prometheus Desmotēs)

Sophokles' Ajax (Aias)

Sophokles' Antigone

Sophokles' Trachinian Women (Trachiniai, Women of Trachis)

Sophokles' Oedipus Tyrannos (Oedipus Rex, Oedipus the King)

Sophokles' Elektra (Electra)

Sophokles' Philoktetes (Philoctetes)

Sophokles' Oedipus at Kolonos (Colonus)

Euripides' Alkestis (Alcestis)

Euripides' Medea

Euripides' Children of Herakles (Heraclidae, Herakleidai)

Euripides' Hippolytos

Euripides' Andromache

Euripides' Hecuba (Hekabē)

Euripides' Suppliant Women (Suppliants, Hiketides)

Euripides' Elektra (Electra)

Euripides' Herakles (Hercules Furens, The Madness of Herakles)

Euripides' Trojan Women (Troades)

Euripides' Iphigeneia among the Taurians (Iphigeneia in Tauris)

Euripides' Ion

Euripides' Helen

Euripides' Phoenician Women (Phoinissai)

Euripides' Orestes

Euripides' Iphigeneia at Aulis

Euripides' Bacchae (Bacchants)

Euripides' Cyclops

[Euripides'] Rhesos

Aristophanes' Acharnians

Aristophanes' Knights (Hippeis, Equites, Horsemen)

Aristophanes' Wasps (Sphēkes, Vespae)

Aristophanes' Peace (Pax, Eirēnē)

Aristophanes' Clouds (Nubes, Nephelai)

Aristophanes' Birds (Ornithes, Aves)

Aristophanes' Lysistrate

Aristophanes' Women at the Thesmophoria (Thesmophoriazousai)

Aristophanes' Frogs (Ranae, Batrachoi)

Aristophanes' Assembly-Women (Ekklesiazousai)

Aristophanes' Wealth (Ploutos)

Menander's The Grouch (Old Cantankerous, Dyskolos)

Menander's Samian Woman (Samia) or Marriage-contract

A Note on Meter

Glossary of Names and Terms

Timeline

Further Reading

Index

Praise for A Guide to Ancient Greek Drama, Second Edition

“The discussion of the contexts of ancient Greek drama, its performance, ancient and modern, is thoroughgoing and scholarly. The synopses of the plays and interpretations are invaluable tools – a must on any scholar's bookshelf.”

Robin Bond, University of Canterbury

“Covering all the genres of Greek drama, and bringing in what is known about lost plays as well as those that we have, A Guide to Ancient Greek Drama, Second Edition is comprehensive, balanced, up-to-date, reliable, and readable. It presents a huge amount of information, but in a distinctive and winning voice.”

Ruth Scodel, University of Michigan

“With revised sections on Sophocles and politics, and new discussions of Reception and vase-painting, the second edition of this handbook will be helpful to both students and scholars.”

C.W. Marshall, University of British Columbia

Praise for the first edition

“This thoughtfully designed guide not only provides background, play summaries, critical analysis, and bibliography, but also surveys modern approaches to Greek drama. Comprehensive, reliable, and enlightening, it will be a boon to students and their teachers.”

Justina Gregory, Smith College

BLACKWELL GUIDES TO CLASSICAL LITERATURE

Each volume offers coverage of political and cultural context, brief essays on key authors and historical figures, critical coverage of the most important literary works, and a survey of crucial themes. The series provides the necessary background to read classical literature with confidence.

Published

A Guide to Hellenistic Literature

By Kathryn Gutzwiller

A Guide to Ancient Greek Drama, second edition

By Ian C. Storey and Arlene Allan

In preparation

A Guide to Epic Poetry

Patricia Parker and Brendon Reay

This edition first published 2014

© 2014 John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Edition history: Blackwell Publishing Ltd (1e, 2005)

Registered Office

John Wiley & Sons Ltd, The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, UK

Editorial Offices

350 Main Street, Malden, MA 02148–5020, USA

9600 Garsington Road, Oxford, OX4 2DQ, UK

The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, UK

For details of our global editorial offices, for customer services, and for information about how to apply for permission to reuse the copyright material in this book please see our website at www.wiley.com/wiley-blackwell.

The right of Ian C. Storey & Arlene Allan to be identified as the authors of this work has been asserted in accordance with the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, except as permitted by the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, without the prior permission of the publisher.

Wiley also publishes its books in a variety of electronic formats. Some content that appears in print may not be available in electronic books.

Designations used by companies to distinguish their products are often claimed as trademarks. All brand names and product names used in this book are trade names, service marks, trademarks or registered trademarks of their respective owners. The publisher is not associated with any product or vendor mentioned in this book.

Limit of Liability/Disclaimer of Warranty: While the publisher and author(s) have used their best efforts in preparing this book, they make no representations or warranties with respect to the accuracy or completeness of the contents of this book and specifically disclaim any implied warranties of merchantability or fitness for a particular purpose. It is sold on the understanding that the publisher is not engaged in rendering professional services and neither the publisher nor the author shall be liable for damages arising herefrom. If professional advice or other expert assistance is required, the services of a competent professional should be sought.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Storey, Ian Christopher, 1946–

A guide to ancient Greek drama / Ian C. Storey & Arlene Allan. – Second edition.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.ISBN 978-1-118-45512-8 (pbk. : alk. paper) – ISBN 978-1-118-45511-1 (epub) – ISBN 978-1-118-45513-5 (mb) – ISBN 978-1-118-45514-2 (epdf) 1. Greek drama–History and criticism–Handbooks, manuals, etc. I. Allan, Arlene. II. Title.

PA3131.S83 2014

882′.0109–dc23

2013030058

Paperback 9781118455128

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

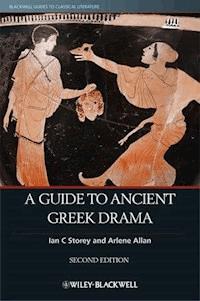

Cover image: Red-figure krater with detail of two actors, 5th century BC, Valle Trebba. Ferrara, Archaeological Museum. © 2013. Photo Scala, Florence - courtesy of the Ministero Beni e Att. Culturali

Cover design by Richard Boxhall Designs Associates

Dedicated to the memory ofKathryn (Kate) Grace Bosher(1974–2013)

Preface to the First Edition

In this Guide we have attempted to provide an introduction to all three of the genres that comprised ancient Greek drama. Many critical studies focus solely on tragedy or on comedy with only a nodding glance at the other, while satyr-drama often gets lost in the glare of the more familiar genres. We begin with a consideration of the aspects and conventions of ancient Greek drama, so like and at the same time different from our own experience of the theater, and then discuss the connections that it possessed with the festivals of Dionysos and the polis of Athens. Was attending or performing in the theater in the fifth and fourth centuries a “religious” experience for those involved? To what extent was ancient drama a political expression of the democracy of the Athenian polis in the classical era?

We consider first tragedy, the eldest of the three dramatic sisters, both the nature of the genre (“serious drama”) and the playwrights that have survived, most notably the canonical triad (Aeschylus, Sophokles, Euripides), but also some of the lesser lights who entertained the spectators and won their share of victories. We have given satyr-drama its own discussion, briefer to be sure than the others, but the student should be aware that it was a different sort of dramatic experience, yet still part of the expected offerings at the City Dionysia. As Old Comedy is inextricably bound up with Aristophanes, much of the discussion of that poet will be found in the section on Old Comedy proper as well as the separate section devoted to Aristophanes. A short chapter addresses how one should watch or read (and teach) Greek drama and introduces the student to the various schools of interpretation. Finally we have provided a series of one-page synopses of each of the forty-six reasonably complete plays that have come down to us, which contain in brief compass the essential details and issues surrounding each play.

We would thank our students and colleagues at Trent University, who over the years have been guinea-pigs for our thoughts on ancient Greek drama. Martin Boyne, in particular, gave us much useful advice as the project began to take shape. Kevin Whetter at Acadia University read much of the manuscript and provided an invaluable commentary. Colleagues at Exeter University and the University of Canterbury in New Zealand have also been sources of ongoing advice and support. Kate Bosher (Michigan) very kindly gave us the benefit of her research into Epicharmos. Karin Sowada at the Nicholson Museum in Sydney has gone out of her way to assist in providing illustrations for the book. We have enjoyed very much working with the staff at Blackwell. Al Bertrand, Angela Cohen, Annette Abel, and Simon Alexander have become familiar correspondents, responding unfailingly to our frequent queries.

Drama is doing, and theater watching. We both owe much to the Classics Drama Group at Trent University, which since 1994 has sought to bring alive for our students the visual and performative experience of ancient drama. This volume is dedicated to them, with admiration and with thanks.

Preface to the Second Edition

Commenting on the revision of Eupolis' lost comedy Autolykos (420 bc), an ancient scholar defines the technical term “revision” as: “when a book is rewritten from the original version, having the same plot and most of the same text, but with some things removed from the previous version, some things added, and some things altered.” This might well serve as an apt description of the second edition of our guide to ancient Greek drama. Much of the presentation of basic facts about the production of ancient plays, information about the dramatists, and details of the dramas themselves, has remained as it was in the original edition, taking into account the significant studies of the past ten years. However, in the first chapter we have conflated into one sub-section (“Drama, Dionysos, and the Polis”) the discussions of the connections of Greek drama to its patron god Dionysos and to the city (polis) in which most of the dramas that we have were produced, Athens. In so doing we are trying not to create artificial pigeon-holes in which to insert discussions of drama as “religious” or “political,” but to see the overall experience of all concerned (poets, performers, officials, spectators) as one that directly affected their lives and identities as member of ancient Greek polis.

Similarly in chapter 2 we have for the most part reproduced the original descriptive material, but the section on Sophokles and the polis has been expanded considerably. Whereas for Aeschylus and Euripides it is possible to see specific contemporary issues reflected in their dramas, Sophokles seems to be dramatizing the issues of the polis more subtly, showing how matters of general import are worked out on and by individual men and women. We speculate whether Sophokles should not be considered the most politically engaged of the three extant tragic poets. To chapter 4 (“Greek Comedy”) we have added two new discussions: one on the comic poet, Alexis, who had somehow slipped between the two stools of Middle and New Comedy, and the other on the so-called phlyax-vases, some of which are now regarded as illustrating scenes from Athenian comedy, both Old and Middle. We have also expanded our discussion of later comedy, in part to take into account the excellent recent treatments by Arnott (2010), Ireland (2010), and Traill (2008).

Chapter 5 (“Approaching Greek Drama”) has been almost entirely recast. We have retained most of the approaches outlined in the previous edition, but re-organized them into groups with related themes. “Formal Criticism” includes textual criticism and commentary, the “New” criticism by which ancient dramas are read as works of literature, and the comparative approach (or “version”). Within “Interdisciplinary Approaches” we have grouped structuralist readings, drama and ritual, gender-based studies, and psychological analyses. A third category, “Visual Interpretations,” includes both the conventions of ancient stagecraft and also the depiction of scenes from tragedy, comedy, and satyr-drama, principally on vases and in the form of terracotta statuettes. A final section, “Reception Studies” comprises the “classical tradition” as applied to drama and what we now call “performance studies.”

To the appendices we have added a “Timeline,” providing in three parallel columns: military and external events having to do with the ancient Greek world, political and social events (principally at Athens), and the development of Greek drama. These cover the period from roughly 600 bc to 300 bc. The other major change in the second edition will be found in the area of “Further Reading.” The presentation of bibliography in the first edition in various sub-sections proved to be cumbersome in appearance and difficult to use. At the end of each chapter we now provide a short series of “recommended reading,” usually five or so annotated entries on each of a number of topics raised in that chapter. At the end of the volume will be found a full list of “Further Reading,” covering both works cited in the text and our suggestions for other books, articles, and collections of essays that will (we hope) be of use to both student and instructor.

We would again like to thank our students and colleagues at Trent University and the University of Otago, who have often been the first recipients of our thoughts on ancient Greek drama and have in turn offered many insightful comments. The Classics Drama Group (the Conacher Players) at Trent University, now in their twentieth year, continues to flourish and provide us with opportunities to examine how ancient plays were (and can still be) performed. Dr. Martin Boyne (Trent) gave us a great deal of advice as the project first developed and has done so again for this second edition. We are especially grateful to those who reviewed the first edition and provided a wealth of useful suggestions on how to improve the second. We would acknowledge with thanks the support from James Morwood (Oxford), Eric Dugdale (Gustavus Adolphus), Robin Bond (Canterbury), Toph and Hallie Marshall (UBC), George Kovacs (Trent), and Donald Sells (Michigan). We have enjoyed very much working (again) with the staff at Wiley-Blackwell. Haze Humbert, Rebecca du Plessis, and Ben Thatcher have become familiar correspondents, responding unfailingly to our frequent queries. Many thanks also to Bryn Snow for doing the index to this edition.

Finally and on a very sad note, we acknowledge the contributions to both editions made by Kathryn (Kate) Bosher (Northwestern), who gave us the benefit of her expert knowledge of Epicharmos and the tradition of drama in the Greek West. Kate's early and unexpected passing in March 2013 shocked and dismayed her many colleagues and admirers. This revised edition of our guide to ancient Greek drama is thus dedicated to her memory.

List of Figures

1.1 Theater of Dionysos, Athens

1.2 Theater at Epidauros

1.3 Seating in the fifth-century theater at Argos

1.4 Lysikrates Monument, Athens

1.5 Theater of Dionysos, looking toward the Acropolis

1.6 South slope of the Acropolis (artist’s reconstruction)

1.7 Theater at Megalopolis

1.8 Theater at Delphi

1.9 Throne of the Priest of Dionysos Eleuthereus

1.10 Tragic performers dressing for their role as maenads

1.11 Costumed actor holding his mask

1.12Aulos-player

2.1 Basel Choristers

2.2 Resolution (Euripides' securely dated plays)

2.3 Resolution (Euripides' extant tragedies)

2.4 Tableau scene from a volute-krater, ca. 340s

3.1 The Pronomos Vase

3.2 Performers in a satyr-drama

3.3 Depiction of Satyr and maenad

4.1 Padded dancers

4.2 The Chorēgoi Vase

4.3 The Würzburg Telephos

4.4 Cairo Papyrus, Plate XLV

5.1 Two scenes illustrating the opening scene of Aeschylus' Libation-Bearers

5.2 The “Cleveland Medea”

5.3 Tableau scene likely influenced by the death scene in Euripides' Alkestis

5.4 “Orestes at Delphi”

List of Maps and Plans

0.1 Map of the Eastern Mediterranean

0.2 Map of Greece

1.1 Map of Attica

1.2 Map of Athens

1.3 Theater of Dionysos (classical period)

1.4 Theater at Thorikos

Abbreviations and Signs

“F” designates the fragments of the dramatic poets. For tragedy these are cited from the volumes of TrGF, and for comedy from PCG. Several volumes in the Loeb Classical Library contain the text of most fragments with an English translation and some notes: Sommerstein 2008 vol. 3 (Aeschylus), Lloyd-Jones 1996 vol. 3 (Sophokles), Collard & Cropp 2008 (Euripides), Henderson 2007 vol. 5 (Aristophanes), Storey 2011 (the other poets of Old Comedy), and Arnott 1990 (Menander). “D” designates a play performed at the City Dionysia at Athens; “L” a play performed at the Lenaia at Athens.

All dates are bc, unless otherwise indicated. Except for some names which have become too familiar to alter (Homer, Aeschylus, Plato, Aristotle, Menander ∼ more properly Homeros, Aischylos, Platon, Aristoteles, Menandros), we have used Hellenized spellings (“k” to represent Greek kappa, endings in “-os” rather than the Latinate “-us”). Among other things it does allow the student to distinguish a Greek author (Kratinos) from a Roman one (Plautus).

Map 0.1 Map of the Eastern Mediterranean.

Map 0.2 Map of Greece.

1

Aspects of Ancient Greek Drama

Drama

While ancient Greek drama appears first during the sixth century bc and can be traced well down into the third, most attention is paid to the fifth century at Athens, when and where most of the nearly fifty plays that we possess were produced. In this study we shall introduce the three distinct genres of Greek drama: serious drama or tragedy (traditionally instituted in 534), satyr-drama (added ca. 500), and comedy (formally introduced at Athens in the 480s, but which flourished at the same time in Syracuse).

Drama is action. According to Aristotle (Poetics 1448a28) dramatic poets “represent people in action,” as opposed to a purely third-person narrative or the mixture of narrative and direct speech as found in Homer. We begin appropriately with the Greek word δρᾶμα (drāma), which means “action” or “doing.” Aristotle adds that the verb drān was not an Attic word (“Attic” being the Greek dialect spoken at Athens), Athenians preferring to use the verb prattein and its cognates (pragma, praxis) to signify “action.” Whether this was true or not does not matter here – that drān is common in Athenian tragedy, but not in the prose writers, may support Aristotle's assertion. Both Plato and Aristotle, the two great philosophers of the fourth century, defined drama as a mimēsis, “imitation” or “representation,” but each took a different view of the matter. Mimēsis is not an easy word to render in English, since neither “imitation” nor “representation” really hits the mark. We have left it in Greek transliteration. For Plato mimēsis was something disreputable, something inferior, something the ideal ruler of his ideal state would avoid. It meant putting oneself into the character of another, taking on another's role, which in many Greek myths could be a morally inferior one, perhaps that of a slave or a woman. Plato would have agreed with Polonius in Hamlet, “to thine own self be true.” But Aristotle considered mimēsis not only as something natural in human nature but also as something that was a pleasure and essential for human learning (Poetics 1448b4–8): “to engage in mimēsis is innate in human beings from childhood and humans differ from other living creatures in that humans are very mimetic and develop their first learning through mimēsis and because all humans enjoy mimetic activities.”

Drama is “doing” or “performing,” and performances function in different ways in human cultures. Religion and ritual immediately spring to mind as one context: the elaborate dances of the Shakers; the complex rituals of the Navajo peoples; the mediaeval mystery plays, which for a largely illiterate society could provide both religious instruction and ritual re-enactment as well as entertainment. Drama can also encompass “science” – the dances of the Navajo provide both a history of the creation of the world and a series of elaborate healing rituals. Dramatic performances can keep the memory of historical figures and events alive. Greek tragedy falls partly into this category, since its themes and subjects are mainly drawn from an idealized heroic age several hundred years in the past. Some of the subjects of Greek tragedy are better described as “legendary” rather than “mythical,” for legend is based on historical events, elaborated admittedly out of recognition, but real nonetheless. The Ramlila play cycles of northern India were a similar mixture of myth and history, and provided for the Hindus the same sort of cultural heritage that Greek myths did for classical Greece. An extreme example are the history-plays of Shakespeare, in particular his Richard III, which was inspired by the Tudor propaganda campaign aimed at discrediting the last of the Plantagenets. Finally humans enjoy both acting in and watching performances. Aristotle was right to insist that mimēsis is both innate to humanity and the source of natural pleasure. We watch plays because they give us the pleasure of watching a story-line unfold, an engagement with the characters, and a satisfying emotional experience.

Another crucial term is “theater.” Thea- in Greek means “observe,” “watch,” and while we tend to speak of an “audience” and an “auditorium” (from the Latin audire, “to hear”), the ancients talked of “spectators,” and the “watching-place.” The noun theatron (“theater”) refers both to the physical area where the plays were staged, more specifically to the area on the hillside occupied by the spectators, and also to the spectators themselves, much as “house” today can refer to the theater building and to the audience in that building. Comedians were fond of breaking the dramatic illusion and often refer openly to theatai (“watchers”) or theōmenoi (“those watching”).

Modern academic discussions make a distinction between the study of “drama” and “theater.” A university course or a textbook on “drama” tends to concentrate more on the words of the text that is performed or read. Dramatic critics approach the plays as literature and subject them to various sorts of literary theory, and often run the risk of losing the visual aspect of performance in an attempt to “understand” or elucidate the “meaning” of the text. The reader becomes as important as the watcher, if not more so. Greek drama slips easily into a course on ancient literature or world drama, in which similar principles of literary criticism can be applied to all such texts.

But the modern study of “theater” goes beyond the basic text as staged or read and has developed a complex theoretical approach that some text-based students find daunting and at time impenetrable. Fortier writes well here:

Theater is performance, though often the performance of a dramatic text, and entails not only words but space, actors, props, audience, and the complex relations … Theater, of necessity, involves both doing and seeing, practice and contemplation. Moreover, the word “theory” comes from the same root as “theater.” Theater and theory are both contemplative pursuits, although theater has a practical and a sensuous side which contemplation should not be allowed to overwhelm.*

The study of “theater” will concern itself with the experience of producing and watching drama, before, during, and after the actual performance of the text itself. Theatrical critics want to know about the social assumptions and experiences of organizers, authors, performers, judges, and spectators. In classical Athens plays were performed on a public occasion, supported from the state treasury, in a theater placed next to the shrine of a god and as part of a festival of that god, in broad daylight where spectators would be conscious of far more than the performance unfolding below – of the city and country around them and of their own existence as spectators.

Ours is meant to be a guide to Greek drama, rather than to Greek theater. Our principal concern will be the texts themselves and their authors and, although such an approach may be somewhat out of date, the intentions of the authors themselves. But we do not want to lose sight of the practical elements that Fortier speaks of, especially the visual spectacle that accompanied the enactment of the recited text, for a picture is worth a thousand words, and if we could witness an ancient production, we would learn incalculably more about what the author was doing and how this was received by his original “house.” Knowing the conventions of the ancient theater assists also with understanding why certain scenes are written the way they are, why characters must leave and enter when they do, why crucial events are narrated rather than depicted.

Drama and the poets

Homer (eighth century) stands not just at the beginning of Greek poetry, but of Western literature as we know it. His two heroic epics, Iliad (about Achilles, the Greek hero of the Trojan War) and Odyssey (the return of Odysseus [Ulysses] from that war), did much to establish the familiar versions of the myths about both gods and men. Homer is the great poet of classical Greece, and his epics, along with what we call the “epic cycle” – lost poems, certainly later than Homer, that completed the story of the Trojan War, as well as another epic cycle relating the events at Thebes – formed the backdrop to so much later Greek literature, especially for the dramatists. Much of the plots, characters, and language come from Homer – Aeschylus is described as serving up “slices from the banquet of Homer” – and the dramatic critic needs always to keep one eye on Homer, to see what use the poets are making of his seminal material. For example, Homer created a brilliantly whole and appealing, if somewhat unconventional, character in his Odysseus, but for the dramatists of the fifth century Odysseus becomes a one-sided figure: the paragon of clever talk and deceit, the evil counselor, and in one instance (Sophokles' Ajax) the embodiment of a new and enlightened sort of heroism. Homer's Achilles is one of the great examples of the truly “tragic” hero, a man whose pursuit of honor causes the death of his dearest friend and ultimately his own doom, but when he appears in Euripides' Iphigeneia at Aulis, we see an ineffectual youth, full of sound and fury, and unable to rescue the damsel in distress.

Of the surviving thirty-three plays attributed to the tragedians, only two dramatize material from Homer's Iliad and Odyssey (Euripides' satyr-drama Cyclops [Odyssey 9] and Rhesos of doubtful authenticity [Iliad 10]), but we do know of several lost plays that also used Homeric material. Homer may be three centuries earlier than the tragedians of the fifth century, but his influence upon them was crucial. Homer himself was looking back to an earlier age, what we call the late Bronze Age (1500–1100), a tradition which he passed on to the dramatists. Both Homer and the tragedians are depicting people and stories not of their own time, but of an earlier idealized age of heroes.

In the seventh and sixth centuries heroic epic began to yield to choral poetry (often called “lyric,” from its accompaniment by the lyre). These were poems intended to be sung, usually by large choruses in a public setting. Particularly important for the study of drama are the grand poets Stesichoros (ca. 600), Bacchylides (career: 510–450), and Pindar (career: 498–440s), who took the traditional tales from myth and epic and retold them in smaller portions, consciously reworking the material that they had inherited. They used a different meter from Homer, not the epic hexameter chanted by a single bard, but elaborate “lyric” meters, sung by large choruses. No work by Stesichoros has survived intact, but we know he wrote poem on the Theban story, one of tragedy's favorite themes; an Oresteia, containing significant points of contact with Aeschylus' Oresteia; and a version of the story of Helen that Euripides will take up wholesale in his Helen. Poem 16 by Bacchylides tells the story of Herakles' death at the hands of his wife, much as Sophokles dramatizes the story in his Trachinian Women, and it is not clear whether Bacchylides' poem or Sophokles' tragedy is the earlier work. Pindar in Pythian 11 (474) will anticipate Aeschylus' Agamemnon (458) by presenting Klytaimestra's various motives for killing her husband.

Why Athens?

Most, if not all, of the plays we have were originally written and performed at Athens in the fifth and fourth centuries. Thus much of our study will be centered upon Athens, although theaters and dramatic performances were not exclusive to Athens. Argos had a reasonably sized theater in the fifth century, while at Syracuse, the greatest of the Greek states in the West, there was an elaborate theater and a tradition of comedy by the early fifth century. But it was at Athens in the late sixth and early fifth centuries that the three genres of drama were formalized as public competitions. Traditionally the first official performance of tragedy is credited to Thespis in 534, but as the records of the dramatic performances appear to begin around 501, many prefer to date the actual beginning of tragedy (and thus of Greek drama) to that later date. But whatever date one chooses (see the next chapter), one must understand the political and social background of Athens, both in the sixth century and in the high classical age of democracy.

In the sixth century Athens was not yet the leading city of the Greek world, politically, militarily, economically, or culturally, that she would become in the fifth century. The principal states of the sixth century in the Greek homeland were Sparta, Corinth, Sikyon, and Samos, and some ancient sources do record some sort of dramatic performances at Corinth and Sikyon earlier in the sixth century. Athens was an important city, but not in the same league as these others. By the early sixth century Athens had brought under her central control the region called “Attica” (map 1.1). This is a triangular peninsula roughly forty miles in length from the height of land that divides Attica from Boiotia (dominated by Thebes) to the south-eastern tip of Cape Sounion, and at its widest expanse about another forty miles. Athens itself lies roughly in the center, no more than thirty miles or so from any outlying point – the most famous distance is that from Athens to Marathon, just over twenty-six miles, covered by the runner announcing the victory at Marathon in 490 and thus the length of the modern marathon race. Attica itself was not particularly rich agriculturally – the only substantial plains lie around Athens itself and at Marathon – nor does it supply good grazing for cattle or sheep. But in the late sixth century Athens underwent an economic boom through the discovery and utilization of three products of the Attic soil: olives and olive oil, which rapidly became the best in the eastern Mediterranean; clay for pottery – Athenian vase-ware soon replaced Corinthian as the finest of the day; and silver from the mines at Laureion – the Athenian “owls” became a standard coinage of the eastern Mediterranean.

Map 1.1 Map of Attica. Italicized sites are known to have had a theater.

Coupled with this economic advance were the political developments of the late sixth century. The Greek cities of the seventh and sixth centuries experienced an uneasy mix of hereditary monarchy, factional aristocracy, popular unrest (at Athens especially over debts and the loss of personal freedom), and “tyranny.” To us “tyranny” is a pejorative term, like “dictatorship,” but in Archaic Greece it meant “one-man-rule,” usually where that one man had made himself ruler, sometimes rescuing a state from an internal stasis (“civil strife”). Various lists of the seven wise men of ancient Greece include as many as four tyrants. At Athens the tyrant Peisistratos seized power permanently in the mid 540s following a period of internal instability and ruled to his death in 528/7. He was succeeded by his son Hippias, who was expelled from Athens in 510 by an alliance of exiled aristocrats, the Delphic oracle, and the Spartan kings.

In the fifth century tyrannos (“tyrant”) was a pejorative term, used often as an accusation against a political opponent, and the first use of ostracism at Athens (a state-wide vote to expel a political leader for ten years) in 487 was to exile “friends of the tyrants.” But in the fourth century the age of the tyrants (546–510) was remembered as an “age of Kronos,” a golden age before the defeat of Athens during the democracy. The tyrants set Athens on the road to her future greatness in the fifth century under the democracy. They provided political and economic stability after a period of bitter economic class-conflict in the early sixth century, attracted artists and poets to their court at Athens, inaugurated a building program that would be surpassed only by the grandeur of the Acropolis in the next century, established or enhanced the festival of the Panthenaia, the four-yearly celebration of Athene and of Athens, and instituted contests for the recitation of the Homeric poems, establishing incidentally the first “official” text of Homer. The tyrants quelled discontent and divisions within the state and instilled a common sense of identity that paved the way for Athens' greatness in the next century. Peisistratos created also a single festival of Dionysos at Athens, the City Dionysia in late March. This did not replace, but augmented the Rural Dionysia celebrated locally throughout Attica in late autumn. As late March marked the opening of the sailing season and the arrival in Athens of overseas visitors, the City Dionysia was thus a festival for all Athenians and their guests. It was at this festival that tragedy was first performed.

Economic success and cultural advancement were followed by political and military developments, which propelled Athens into the forefront of Greek city-states by the middle of the fifth century. First tyranny was replaced by democracy. Political maneuvering following the expulsion of Hippias in 510 resulted in the establishment of a democratic form of government in 507, eventually possessing a popular assembly (ekklēsia), elected officials, a jury-system, and two important watch-words: isonomia (“equality under the law”) and parrhēsia (“freedom of speech”). Next came the successful defense against a threat from the powerful Persian empire to the east, three invasions of Greece (492, 490, 481–479), thwarted by crucial victories at Marathon (490) and Salamis (480), in which Athens played a key role. After the wars a league established under Athens' leadership to defend against future Persian attacks had by the mid 450s become an Athenian archē (“empire”). A massive building program replaced the buildings destroyed by the Persians, of which the best-known is the Parthenon on the Acropolis. An atmosphere of success and self-confidence dominated Athens in the fifth century, much in the same way that success in World War II, coupled with their sense of manifest destiny, catapulted the United States into a position of world leadership.

The time-frame

On whatever date we prefer for its formal institution, tragedy was not “invented” overnight and we may imagine some sort of choral performances in the sixth century developing into what would be called “tragedy.” Thus, even though the first extant play (Aeschylus' Persians) belongs in 472, we need to begin our study of drama in the sixth century. Like any form of art drama has its different periods, each with its own style and leading poets. The one we know best corresponds with Athens' ascendancy in the Greek world (479–404), from which we have the canonical “Three” of tragedy (Aeschylus, Sophokles, Euripides), forty-six complete or reasonably complete plays, as well as a wealth of fragments and testimonia about lost plays and authors. New tragedies continued to be written and performed in the fourth century and well into the third, but along with the new arose a fascination with the old, and competitions were widened to include “old” or revived plays. In the third century tragic activity shifted to the scholar-poets of Alexandria, but here it is uncertain whether these tragedies were meant to be read rather than performed, and if performed, for how wide an audience.

The evidence suggests that satyr-drama is a later addition to the dramatic festivals; most scholars accept a date of introduction ca. 501. In the fifth century one satyr-drama would follow the performance of the three tragedies by each competing playwright, but by 340 satyr-drama was divorced from the tragic competitions and only one performed at the opening of the festival. Thus at some point during the fourth century satyr-drama becomes its own separate genre.

Formal competitions for comedy began later than tragedy and satyr-drama, the canonical date being the Dionysia of 486. The ancient critics divided comedy at Athens into three distinct chronological phases: Old Comedy, roughly synonymous with the classical fifth century (486 to ca. 385); Middle Comedy (ca. 385–325, or “between Aristophanes and Menander”); New Comedy (325 onward). We have complete plays surviving from the first and third of these periods. The ancients knew also that comedy flourished at Syracuse in the early fifth century and that there was something from the same period called “Megarian comedy.”

The evidence

We face two distinct problems in approaching Greek drama: the distance in time and culture from our own, and the sheer loss of evidence. We are dealing with texts that are nearly 2500 years removed in time, written in another language and produced for an audience with cultural assumptions very different from our own. “The past is a foreign country: they do things differently there,” wrote L.P. Hartley, and we should not react to reading (or watching) an ancient Greek drama in the same way that we approach a play by Shakespeare or Shaw or Pinter.

The actual evidence is of four sorts: the texts themselves, literary testimonia, physical remains of theaters, and visual representations of theatrical scenes. So far the manuscript tradition and discoveries on papyrus (see fig. 4.4) have yielded as complete texts thirty-one tragedies, one satyr-drama, one quasi-satyr-drama, and thirteen comedies. But these belong to only five (perhaps six or seven) distinct playwrights, out of the dozens that we know were active on the Greek stage. We often assume that Aeschylus, Sophokles, and Euripides (for tragedy), and Aristophanes and Menander (for comedy) were the best at their business, but were they representative of all that the Athenians watched during those two centuries? Within these individual authors we have only six or seven plays out of eighty or so by Aeschylus, seven out of 120 by Sophokles, eighteen out of ninety by Euripides, eleven comedies out of forty by Aristophanes, and only two comedies by Menander from over 100. On what grounds were these selections made, by whom, for whom, and when? Are these selected plays representative of their author's larger opus? For Euripides we have both a selected collection of ten plays and an alphabetical sequence of nine plays that may be more representative of his work as a whole.

We do not possess anything remotely close to the scripts of the original productions or to the official texts that were established by Lykourgos ca. 330 and then passed to the Library in Alexandria. We have some remains preserved on papyrus from the Roman period, most notably Menander's The Grouch, virtually complete on a codex from the third century ad, but the earliest manuscripts of Greek drama belong about ad 1000, and these are the products of centuries of copying and recopying. Dionysos in Frogs (405) talks of “sitting on my ship reading [Euripides'] Andromeda” and for the fifth century we know of book-stalls in the marketplace; these would not have been elaborate “books” in our sense of the word, but very basic texts allowing the reader to recreate his experience in the theater. The manuscripts and papyri present texts in an abbreviated form, with no division between words, changes of speaker often indicated (if at all) by an underlining or a dicolon, no stage directions – almost all the directions in a modern translation are the creation of the translator – and very frequent errors, omissions, and additions to the text. For plays such as Aeschylus' Libation-Bearers and Aristophanes' Women at the Thesmophoria we depend on one manuscript only for a complete text of the play.

In addition to the actual texts, we have considerable literary testimonia about the dramatic tradition generally and about individual plays and personalities. Most important is Aristotle's Poetics, a sketchily written treatise, principally on tragedy and epic, dating from ca. 330, but with some general introductory comments on the early history of drama. Aristotle was himself not an Athenian by birth, although resident there for many years, and wrote 100 years after the high period of Attic tragedy. The great question in dealing with Poetics is whether Aristotle knows what he is talking about, or whether he is extrapolating backwards in much the same manner as a modern critic. He would have seen plays performed in the theater, both new dramas of the fourth century and revivals of the old masters, and he did have access to much documentary material that we lack. An early work was his Production Lists, the records of the productions and victories from the inception of the contests ca. 501. He would have had access to writers on drama and dramatists; the anecdotes of Ion of Chios, himself a dramatist and contemporary of Sophokles; Sophokles' own work On the Chorus; and perhaps the lost work by Glaukos of Rhegion (ca. 400), On the Old Poets and Musicians. Thus his raw material would have been far greater than ours. But would this pure data have shed any light on the early history of the genre? Was he, at times, just making an educated guess? When Aristotle makes a pronouncement, we need to pay attention, but also to wonder how secure is the evidence on which he bases that conclusion.

His Poetics is partly an analytical breakdown of the genre of tragedy into its component parts and partly a guide for reader and playwright, and contains much that is both hard to follow and controversial: the “end” of tragedy is a katharsis of pity and fear (chapter 6); one can have a tragedy without character, but not without plot; the best tragic characters are those who fall into misfortune through some hamartia (chapter 13). This last term is often mistranslated as “tragic flaw.” But this would give Greek tragedy an emphasis on character, whereas Aristotle at this point (chapters 7–14) is discussing tragic plots. It is better rendered as “a mistake made in ignorance,” and as such restores Aristotle's emphasis on plot.

Other useful sources include the Attic orators of the fourth century, who often quote from the tragic poets to reinforce their rhetorical points. For example, Lykourgos, the fourth-century orator responsible for the rebuilding of the theater at Athens ca. 330, gives us fifty-five lines from Euripides' lost Erechtheus, in which a mother consents to the sacrifice of her daughter to save Athens. The fourth book of the Onomasticon (“Thesaurus”) by Pollux (second century ad) contains much that is useful about the ancient theater, especially a list of technical terms and a description of the masks worn by certain comic type-characters. The Roman architectural writer, Vitruvius (first century ad), has much to say about theatrical buildings especially of the Hellenistic period. The “book fragments” of the lost plays are usually quotations from a wide variety of ancient and mediaeval writers. Two in particular are useful for the student of drama: the polymath Athenaios (second century ad), whose Experts at Dining contains a treasury of citations, and Stobaios (fourth/fifth century ad), a collector of familiar quotations. The first-century-ad scholar, Dion of Prusa, sheds light on the three tragedies on the subject of Philoktetes and the bow of Herakles, by summarizing the plots and styles of all three – useful, since we possess only the version by Sophokles (409).

Inscriptions provide another source of written evidence. The ancients would display publicly their decrees, rolls of officials, casualty lists, and records of competitions. One inscription contains a partial list of the victors at the Dionysia in dithyramb, comedy, and tragedy (IG ii2 2318), another presents the tragic and comic victors at both festivals in order of their first victory (IG ii2 2325), a Roman inscription lists the various victories of Kallias, a comedian of the 430s, in order of finish (first through fifth). Two inscriptions (IG ii2 2320, 2323) give invaluable details about the contests at the Dionysia for 341, 340, and 311, especially that by 340 satyr-drama was performed separately at the start of the festival. A decree from Aixone (312 – SEG 36.186) records the honors given by that deme to two chorēgoi who have performed their duties with distinction.

As physical evidence the remains of hundreds of Greek and Roman theaters are known, ranging from the major sites of Athens, Delphi, Epidauros, Dodona, Syracuse, and Ephesos to small theaters tucked away in the backwoods. The actual physical details of a Greek theater will be discussed below, but some general comments are appropriate here. Most of the theaters are not in their fifth-century condition, since major rebuilding took place in the fourth century, in the Hellenistic period (300–30 bc), and especially under Roman occupation. When the tourist or the student visits Athens today, the theater that he or she sees (fig. 1.1) is not the structure that Aeschylus or Aristophanes knew. We see curved stone seats, reserved seating in the front row, a paved orchēstra floor, and an elaborate raised structure in the middle of the orchēstra. We have perhaps been misled by the classical perfection of the famous theater at Epidauros (fig. 1.2) into thinking that this is typical of all ancient theaters. The Athenian theater of the fifth century had straight benches on the hillside, an orchēstra floor of packed earth (an orchēstra that may not have been a perfect circle), and a wooden building at the back of the orchēstra. At Athens and Syracuse later theaters replaced the old on the same site, while at Argos the impressive and large fourth-century theater was built on a new site, the fifth-century theater being more compact and smaller in size, with straight front-facing rows of seating rather than curved (fig. 1.3).

Figure 1.1 Theater of Dionysos, Athens. Photo by Ian Vining.

Figure 1.2 Theater at Epidauros. Photo by Steve Smith.

Figure 1.3 Seating in the fifth-century theater at Argos. Photo by I.C. Storey.

The theaters that we do have, from whatever period of Greek antiquity, tell us much about the physical experience of attending the theater. Audiences were large and sat as a community in the open air – this was not theater of the private enclosed space. Distances were great – to someone in the last row at Epidauros a performer in the orchēstra would appear only a few inches high. Thus theater of the individual expression was out – impossible in fact since the performers wore masks. But acoustics were superb and directed spectators' attention to what was being said or sung. Special effects were limited – the word and the gesture carried the force of the drama. The prominence and centrality of the orchēstra reflect the importance of the chorus – Greek audiences were used to seeing more rather than fewer performers before them.

Most of the visual representations are found on Greek vases. This particular form of Greek art begins to reach its classical perfection with the black figure pottery of the late sixth century (figures appear in black against a red background), and continues with the exquisite red figure (the reverse) of the fifth and fourth centuries. About 520 we start to see representations of public performances, usually marked by the presence of an aulos-player, and then scenes inspired by tragedy, satyr-drama, and comedy.

The vases do not show an actual performance of a tragedy, although one Athenian vase (460–450 – see cover illustration) shows a chorister dressed as a maenad and an actor holding his mask, while another from the 430s shows a pair of performers preparing to dress as maenads (see fig. 1.10). But from 450 onward vases do display scenes clearly influenced by tragedy: the opening-scene of Libation-Bearers (see fig. 5.1), a series of vases depicting Sophokles' early tragedy Andromeda, another group reflecting Euripides' innovative Iphigeneia among the Taurians, the “Cleveland Medea” (see fig. 5.2), a striking fourth-century tableau illustrating the opening scenes of Eumenides (see fig. 5.4), and equally impressive scenes from Sophokles' Oedipus at Kolonos and Euripides' Alkestis (see fig. 5.3). One or two of these show a pillar structure, which may be an attempt to render the central door of the skēnē, but these vases are not depicting an actual tragic performance. The characters do not wear masks, males are often shown heroically nude (or nearly so) instead of wearing the distinctive costume of tragedy, and there is no hint of the aulos-player, a sure sign of a representation of a performance. For satyr-drama the superb Pronomos Vase (see fig. 3.1), from the very end of the fifth century, shows the performers of a satyr-drama by Demetrios in various degrees of their on-stage dress, accompanied by the aulos-player, Pronomos.

For comedy early vases show padded dancers in a celebration (kōmos) and men performing in animal-choruses. Some identify these as the predecessors to comedy. From the fifth century there is not much direct evidence. The Perseus Vase (ca. 420) showing a comic performer on a raised platform before two spectators may or may not reflect a performance in the theater; it might equally well reflect a private performance at a symposium. But there is a wealth of vases from the fourth century, principally from the south of Italy, which show grotesquely masked and padded comic performers with limp and dangling phalloi in humorous situations. For a long time these were thought to be representations of a local Italian farce called phlyakes, but it is now accepted that these reflect Athenian Old and Middle Comedy which, contrary to accepted belief, was performed in the Greek cities of southern Italy. Some vases show a raised stage with steps and the double door of drama and thus are plainly illustrating an actual stage performance. The most famous of these are the Würzburg Telephos (see fig. 4.3), a vase from about 370 which depicts a scene from Aristophanes' Women at the Thesmophoria (411); a vase by Assteas (ca. 350) showing a scene from Eupolis' lost comedy, Demes (417); and the Chorēgoi Vase (see fig. 4.2), which seems to show figures from both comedy and tragedy.

Sculptural representations of drama are less common. A relief from the late fifth century shows three actors holding masks before Dionysos and his consort – some have conjectured that this is the cast of Euripides' prize-winning Bacchae. A stele from Aixone (313/2) records honors accorded to two successful chorēgoi from that deme and displays five comic masks and two crowns as well as a scene of Dionysos with a young satyr. Many terracotta masks from various periods shed valuable light on what comic masks looked like. Scenes from the comedy of Menander (career: 325–290) were often part of the decoration of ancient houses, most notably a fresco in the “House of Menander” in Pompeii (destroyed in ad 79 by the eruption of Vesuvius) and a third-century-ad house in Mytilene on Lesbos, where eleven floor mosaics remain, with a title and named characters that allow us to identify the exact scene depicted.

The Dramatic Festivals

In the city of Athens drama was produced principally at two festivals honoring the god Dionysos, the Lenaia and the City Dionysia. We discuss below the extent to which drama (in particular, tragedy) was a form of “religious” expression and what, if anything, Greek drama had to do with Dionysos. We are concerned here with the details and mechanics of the festivals and the place of drama within them. While the festivals honored the god Dionysos and the plays were performed in a theater adjoining his sacred precinct, they were also state occasions run by the public officials of Athens, part of the communal life of the city (polis). We shall need to consider also the extent to which drama at Athens was “political,” in the various senses of the word.

Dionysos was honored at Athens with a number of celebrations: the Rural Dionysia (held in the local communities of Attica in late autumn); the Lenaia in late January; the Anthesteria (“Flower Time”) in mid-February; and the City Dionysia in late March or early April. While we know that dramatic competitions certainly occurred at some of the Rural Dionysia throughout Attica, the main dramatic festivals were the Lenaia and the City Dionysia. The oldest and principal venue was the City Dionysia, which occupied five days in the Athenian month of Elaphebolion (“Deer Hunt”), corresponding to late March or early April. The tyrant, Peisistratos (ruled mid 540s to 527) is said to have created one splendid Dionysia to be held within the city of Athens. A myth was developed to document the progress of the god Dionysos from Eleutherai, a community on the northern border of Attica, to Athens itself. Since Eleutherai had recently become part of Attica, there would have been also a political element at work here.

Preliminaries to the actual festival included a proagōn (“precontest”) on 8 Elaphebolion, at which the poets would appear with their actors and chorus and give hints about their forthcoming compositions, and on 9 Elaphebolion Dionysos' statue was taken from the precinct of his temple to the Academy on the north-west outskirts of Athens, where the road from Eleutherai approached the city, in preparation for the formal pompē (“parade”) the next day. The actual details and order of events at the festival are not established with certainty, but the following scheme is a probable one for the 430s:

After the festival, a special session of the ekklēsia was convened within the theater, rather than in its usual meeting-place on the Pnyx, to consider the conduct of the festival for that year.

There has been considerable debate whether the number of comedies was cut from five to three during the Peloponnesian War (431–404) and whether these three remaining comedies were moved, one each to follow the satyr-drama on each of three days devoted to tragedy, thus shaving the festival to four days. In the hypotheses to Aristophanes' Clouds (423-D), Peace (421-D), and Birds (414-D), only three plays and poets are given, whereas a Roman inscription records fourth- and fifth-place finishes for Kallias in the 430s and five plays are also attested for the Dionysia in the fourth century. Aristophanes' Wealth was part of a production of five comedies in 388, but it is not known at what festival it was performed. A passage from Birds (414-D) is crucial here: “There is nothing better or more pleasant than to grow wings. If one of you spectators had wings, when he got hungry and bored with the tragic choruses, he could fly off, go home, and have a good meal, and when he was full, fly back to us” (785–9). If the “us” means “comic performers,” which is the natural flow of the passage, then in 414 comedy was performed on the same day as tragedy. Those who deny that comedy was reduced from five productions to three must argue that “us” means the theater generally, that the now refreshed spectator would be returning for a later tragedy. But when a comic chorus uses “us,” it usually refers to its identity as a comic chorus and not as part of the general theatrical community. It is usually assumed that comedy was reduced for economic reasons during the War, but comedy was a controversial genre in the 430s and 420s. We know of one decree forbidding personal humor in comedy from 439 to 436, and of at least two personal attacks by Kleon on Aristophanes in 426 and 423. The reduction may have had as much to do with the now dangerously topical nature of comedy as with economic savings. Comedy also employed more chorus-members and to eliminate two plays was to free up fifty more Athenians for military service.

The dramatic competitions continued to change over the next century, and certain inscriptions yield valuable information about the dramatic presentations around 340, at which time the festival was being re-organized. By 340 the satyr-drama had separated from the tragic presentations and a single such play opened the festival (Timokles' Lykourgos in 340 and someone's Daughters of Phorkos in 339). In 386 an “old tragedy” was introduced into the festival – Euripides' Iphigeneia in 341, his Orestes in 340, and another of his plays in 339. In 341 three tragic poets each presented three tragedies, employing three actors, each of whom performed in one play by each playwright, but in 340 the tragedians have only two plays and two actors each. Sharing the lead actors among all the competing poets would presumably have allowed each to demonstrate their abilities irrespective of the text that they had to interpret and the abilities of the dramatist whose plays they were performing. In 339 we are told that “for the first time the comic poets put on an ‘old’ comedy.” Another inscription shows that dithyrambs for men and boys were still part of the Dionysia in 332–328 and lists the victors in the order: dithyramb, comedy, tragedy.

Map 1.2 Map of Athens.

The Lenaia took place in the Athenian month of Gamelion (“Marriage”), which corresponds to our late January. It was an ancient festival of the Ionian Greeks, to which ethnic group the Athenians belonged. We know little about the purpose and rituals of the Lenaia – mystical elements have been suggested, or a celebration of the birth of Dionysos, or the ritual of sparagmos (eating the raw flesh of the prey). A parade is attested with “jokes from the wagons,” that is, insults directed at those watching, as well as a general Dionysiac sense of abandon. The evidence suggests that the celebrations of the Lenaia were originally performed in the agora, rather than at the precinct of Dionysos at the south-east corner of the Acropolis (“Dionysos-in-the-Marshes”), where the theater itself would later be located. Whereas the City Dionysia was under the control of the archon eponymous, once the leading political official at Athens, the Lenaia was handled by the archon basileus