Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

'Who says that daughters cannot be heroic?' Once upon a time, history was written by men, for men and about men. Women were deemed less important, their letters destroyed, their stories ignored. Not any more. This is the story of women who went to war, women who stopped war and women who stayed at home. The rulers. The fighters. The activists. The writers. This is the story of Wu Zetian, who as 'Chinese Emperor' helped to spread Buddhism in China. This is the story of Genghis Khan's powerful daughters, who ruled his empire for him. This is the story of Christine de Pizan, one of the earliest feminist writers. This is the story of Victoria Woodhull, who ran for president before she could even vote for one. This is the story of the world – with the women put back in.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 673

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

This book has been selected to receive financial assistance from English PEN’s ‘PEN Translates’ programme, supported by Arts Council England. English PEN exists to promote literature and our understanding of it, to uphold writers’ freedoms around the world, to campaign against the persecution and imprisonment of writers for stating their views, and to promote the friendly co-operation of writers and the free exchange of ideas. www.englishpen.org

The translation of this work was supported by a grant given by the Goethe-Institut London.

Originally published in German as Weltgeschichte für junge Leserinnen by Kein & Aber AG Zürich – Berlin, 2017

This English language edition first published by The History Press, 2019

The History Press

97 St George’s Place, Cheltenham

Gloucestershire, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

Text © Kerstin Lücker and Ute Daenschel, 2017, 2019

Translation © Ruth Ahmedzai Kemp and Jessica West, 2019

Illustrations © Natsko Seki, 2019

Map © Lovelljohns, 2019

The right of Kerstin Lücker and Ute Daenschel to be identified as the Authors of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 7509 9293 0

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed in Turkey by Imak

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

CONTENTS

Preface

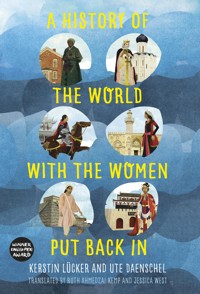

The Women on the Cover

In the Beginning

Prehistory

Sumerians and Babylonians

The Kingdom on the Nile

History Begins in the Indus Valley

The Shang and the Zhou

One God

The Buddha Discovers the Path to Liberation

The Birth of Europe and Ancient Greece

The First Conquerors of the World

The Roman Empire

The Middle Kingdom

The Birth of Christianity

The Imperium Romanum Becomes Christendom

Every End is a New Beginning

The Byzantine Empire

Splendour and Darkness

China’s Middle Ages

Muhammad Hears the Voice of God

Great Things Come from Africa

The Roman Empire Becomes Two

A New State in Eastern Europe

The Roman Empire Splits … Again

The Caliphate of Cairo

The Invention of the Novel

From Castles to Towns

The First Crusade

In the Medieval Courts

Market Towns Flourish and Christendom Flounders

The Mongols

Marguerite Porete and Joan of Arc

The End of the Middle Ages, the Start of the Modern Era

The End of the Byzantine Empire

The Renaissance

The Discovery of America

The Middle Kingdom Shuts Itself Off

Loss of Power and Schism in the Church

Britain Becomes a Trading Power

Everything is on the Move

The Ottoman Empire

Devastating Wars and the Rise of Science

The Glorious Revolution

Absolutism and Enlightenment

The Greats: Frederick and Catherine

The Founding of the United States of America

The Last Continent is Discovered

Olympe de Gouges Declares the Rights of the Woman and Citizen

Revolution and Restoration

The Triumph of the Machine

Darwin and Marx Explain the World

Progress and Regression

The Ming and the Qing

The Fight for Civil Rights

Imperialism: Europeans on the Rampage

Faster!

Resistance

The March of Imperialism: the Europeans Conquer Africa

Britain Against Germany

The Suffragettes

Women are not United

Warfare Gets Harsher

Soldiers March, Women Build Bombs

The British Carve up the Middle East

One World, Two Ideas

The World Falls into an Abyss

The Cold War

Catching up with the Present

Bibliography

About the Authors, Translators and Illustrator

PREFACE

This book was originally intended for young readers. Over time, the focus has changed. More and more adults showed an interest, and it became clear that the book was no longer just addressing younger readers but everyone – male and female, young and old. It has been gratifying that the book has attracted so much interest. However, our adult readers may notice that, in addressing our original target audience, we placed less focus on two key issues that are central to understanding the relationship between men and women: violence and sexuality.

He who holds unchecked power can treat others as he wishes. He can use violence and torture. He can make mistakes and even commit crimes, and then place the blame on others. Very often throughout history, women have not only suffered violence, but have also been blamed for being victims. Many times, they have been accused of goading men into committing violence against them, yet nobody has thought to ask themselves why a woman would choose to do this of her own free will.

Over the course of history, people have accepted and adapted to tremendous change and innovation, be it space exploration or the inventions of railways, cars, planes and smartphones. But the idea that everyone benefits from equal rights for men and women, and from a society based on the dignity and equality of all its members? This is a concept that has taken a very long time to gain acceptance – even though it’s been around for several thousand years.

Over the centuries, history has seen unimaginable atrocities and violence against all genders. And yet violence against women has a special quality: it is an injustice that, for a very long time, wasn’t seen as wrong. For years, many countries’ laws stated that men were entitled to beat their wives.

It could seem like we’re downplaying the suffering involved if we simply write that, throughout history, women have had to serve men, be silent and obedient, and put up with all kinds of injustices being committed against them. And yet we didn’t want that to be our sole focus; there are other aspects to world history too. We didn’t want to limit ourselves to horrific descriptions of horrific situations. Because although history is full of violence, it is also full of occasions where people have successfully overcome violence and embraced values such as equality and the dignity of all people.

‘… History, real solemn history, I cannot be interested in. Can you?’

[…]

‘I read it a little as a duty, but it tells me nothing that does not either vex or weary me. The quarrels of popes and kings, with wars or pestilences, in every page; the men all so good for nothing, and hardly any women at all — it is very tiresome: and yet I often think it odd that it should be so dull, for a great deal of it must be invention.’

Jane Austen, Northanger Abbey

HATSHEPSUT

EIGHTEENTH-DYNASTY EGYPT

The daughter of kings, the wife of kings, the sister of kings and a king herself. Alongside her nephew Thutmose III, Hatshepsut focused her reign on trade, exploration and creating remarkable buildings that still stand today.

SITT AL-MULK

ELEVENTH-CENTURY AFRICA

The de facto caliph who saved a city. Sitt al-Mulk took the throne after her younger brother mysteriously vanished, and tore down his bizarre laws – laws that banned women from leaving their homes or laughing in the street.

EMPRESS THEODORA

SIXTH-CENTURY BYZANTINE EMPIRE

The circus performer who ruled an empire. Theodora ruled side by side with her husband Justin, reshaping the Eastern Roman Empire in their image and creating some of the first laws to protect and aid women.

OLGA OF KIEV

TENTH-CENTURY RUSSIA

The vengeful royal widow who brought Christianity to Russia. Left as regent after her husband was killed by a rival tribe, Olga destroyed the tribe – and then sent envoys to the outside world to learn about Christianity.

CHRISTINE DE PIZAN

FIFTEENTH-CENTURY FRANCE

The woman who wrote ‘I, Christine’, and told the world about her anger. A widow at 25, Christine de Pizan took up her pen to earn a living; in doing so, she challenged the conventions and opinions of medieval France.

CHARLOTTE CORDAY

EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY FRANCE

The revolutionary who murdered to save France. Horrified by the Reign of Terror, Charlotte Corday thought she could save the ideals of revolution by killing journalist Jean Paul Marat – instead, it led to a push for women to stay out of politics.

WU ZETIAN

SEVENTH-CENTURY CHINA

The mother of emperors who took the throne herself. Empress Wu was a woman of contradictions; she ruled with uncompromising violence, but with great foresight that brought prosperity to China.

QIN LIANGYU

SEVENTEENTH-CENTURY CHINA

The general who never lost a battle. After her husband died, Qin Liangyu took up her spear and took over his army, defending Ming-dynasty China against invaders and rebels.

LA MALINCHE

SIXTEENTH-CENTURY MEXICO

The slave who conquered the new world. A noblewoman who had been sold to the Mayans and then gifted to the conquistadors, La Malinche was a translator for Hernán Cortés who helped the Spanish conquer Mexico.

MARGARET HAMILTON

TWENTIETH-CENTURY AMERICA

The software engineer who saved the moon landing. Margaret Hamilton wrote ‘Forget it’, a code to help Apollo 11’s computers prioritise its decisions – without it, it’s doubtful that anyone would have landed on the moon.

HARRIET TUBMAN

NINETEENTH-CENTURY AMERICA

The runaway slave who wanted to stop people suffering like she had. Harriet Tubman escaped to Canada via the Underground Railroad, and then almost immediately turned around and began to work on it herself, becoming one of the most famous anti-abolitionists.

EVERYWHERE

IN THE BEGINNING

Around 13.8 billion years ago: The universe is formed in the Big Bang. Probably.

When we tell the story of our planet, we can’t avoid phrases like ‘maybe’, ‘probably’ and ‘it is thought’.

Around 4.6 billion years ago, it is thought, the Earth formed from a swirling mass of dust and debris orbiting a young, yellow star. Probably. And in the beginning, the Earth was desolate and empty. Maybe. Then, very gradually, over the course of millions of years, minute single-cell organisms evolved into ever more complex lifeforms, until eventually there were gigantic dinosaurs roaming the Earth. It is thought. And somewhere in the world, somewhere in the mists of time, an ape stood up on two legs. Possibly.

Around 4.6 billion years ago: Planet Earth is formed from a swirling mass of dust and debris. Maybe.

But maybe it didn’t happen like this at all. Perhaps the world and its inhabitants developed along these lines but not precisely like this. When we talk about history (the events of the past) and before that prehistory (the events of the far distant past), phrases like ‘probably’ and ‘it is thought’ crop up a lot, simply because there’s so much we can’t tell for sure. Many things that we think of as being fact are not proven to be definitely true, but are the stories that scientists and natural historians have developed to explain the evidence that we have.

Though there might be guesswork involved, our conclusions are usually based on sound reasoning. The past has left a trail, and clues about what really happened can be found all around us. Some of these clues can seem quite ordinary. Take a stone with knife-sharp edges: did somebody sharpen it like that deliberately or did it just break off a cliff?

Other signs that seem easy to understand at first, such as newspapers, letters and chronicles of the year’s events, can be much more complex when looked at closely. When looking at this sort of evidence, we must consider whether the description has been influenced by a particular motive or point of view. Did somebody pay the writer to present them as a hero? Was the book meant as a parable, rather than a realistic account of real-life events? Was a letter written to tarnish someone’s reputation, for no reason other than that the writer didn’t like them? Suddenly, nothing’s as clear-cut any more.

Before any theories or conclusions can be made, thousands of pieces of evidence have to be collected and carefully analysed. Only then can we reach a conclusion or come up with a theory. These theories are then reviewed, revised, and may even be rejected altogether, regardless of how convincing they seemed at first.

When we write history, we have to cut our way through this tangled web. Historians must decide which witnesses to trust and how to interpret the evidence. Only then can we form an opinion. No one can ever discover ‘the truth’, but we may find new ways of looking at the things we do know. By painstakingly piecing together the jigsaw puzzle of history, we can transform that ‘maybe’ into a ‘probably’.

A puzzle with lots of missing pieces

Historians never stop working on this puzzle, even though they know they’ll never get their hands on all the pieces. No matter how exciting or frustrating this job might be, they’re spurred on by the hope that, one day, they’ll find enough pieces to build a more complete picture of the past. Unfortunately, it just so happens that the missing pieces are often the ones that could tell us more about the lives of women.

There are various reasons for this. When telling the history of the world, we focus on the extraordinary, on the events that changed the world. We focus on wars, the founding of states, new religions and inventions – and most of the people who have been responsible for these events have been men. Women, on the other hand, were responsible for looking after the home, the kitchen and the children throughout much of history. For a long time, this was more or less the case all over the world, so men have had more opportunities to become famous and to make their mark on history.

But this isn’t the whole story. Time and time again, women have pushed beyond the boundaries of their conventional role; they’ve done what they felt was right and used their own individual talents to do it. They’ve been rulers and warriors, philosophers and writers, composers and artists, and have shown the world exactly what they can do – when given the chance. There are more important women in history than you might think. Often, though, we just don’t know enough about them. This is because people thought it was wrong for women to do amazing things. It went against their idea of how the world worked. It was men who went out and did extraordinary things; women stayed at home.

For this reason, the men who recorded the events of their era simply disregarded the contribution of women. This started as far back as Ancient Egypt, where the name of the female pharaoh Hatshepsut was chiselled out of the pyramids after her death. Back then, it wasn’t unusual for a jealous Egyptian ruler to remove the names of his predecessors from the historic record – but in the case of Hatshepsut, it wasn’t her existence as a woman that was erased. It was the fact that she had been ‘king’. Some suggest this happened because her successors believed that a woman ruler was a violation of the world order.

Similarly, in Mongolia, a historian discovered a thirteenth-century parchment where the section on women’s history had simply been ripped out. Furthermore, in almost 1,000 years of Roman history, relatively few women are mentioned at all. Whether this was because women were removed from the record later on or because women had fewer opportunities to shine in this warrior society (the more likely scenario!), we know nowhere near enough about the lives of Roman women, and remarkably little of what we do know is noteworthy.

Throughout history, women who dared to intervene or voice an opinion were often portrayed in a negative light. Such women are regularly described as crafty, ruthless, dishonest and wicked. All over the world, chroniclers of history seem to have shared a similar goal: using all the resources at their disposal, they seemed determined to prove that women interfering in politics brings only disaster.

Unfortunately, these attempts to erase women from history have been very successful. Often the only thing we know about female writers is that they were famous. Their writings have disappeared while the works of their male counterparts have been preserved and republished over and over again. There’s correspondence where the only letters surviving are the ones sent by the man: the woman’s letters were either deliberately destroyed or lost through carelessness. Throughout history, forgetfulness has shrouded the lives of women and their work like a veil. Over the past few decades, though, the world’s historians have started searching for the traces left behind by these women, so that we now know more about them today than we did 100 or even 50 years ago. Through the work of these historians, the veil that obscured our view of these women for so long is gradually being lifted.

In this book, when we attempt to put together the pieces of this ‘world history puzzle’, we won’t leave out the many men who have made important contributions to history. If we did, the picture we’d end up with would be just as one-sided and incomplete as the one we have now. We don’t want to rewrite the past, so rather than trying to solve the puzzle with entirely new pieces, we’re going to try to find the missing pieces for the picture we already have.

The history of the world that we tell here has its roots in a version of history that was taught in school textbooks for a long time. That traditional narrative is now viewed critically, and for good reason. It’s no accident that, for us in Europe, ‘world history’ has traditionally begun in Mesopotamia and Ancient Egypt and that treasures from these two regions are kept in the museums of London, Paris and Berlin. This shows just how powerful the Europeans were until very recently. They decided how the history of the world should be told, and to demonstrate how central they were to that history, they simply helped themselves to the treasures they wanted from elsewhere in the world.

Our history of the world is inevitably very European in focus. Why, we could also ask ourselves, does Africa play such a minor role and why do we know so little about such a massive continent? It’s no coincidence that Europe’s museums still haven’t returned precious artworks to Egypt, Greece or any of the other countries they were taken from, despite criticism from all sides. This might perhaps be the greater injustice than being side-lined from world history. But this doesn’t mean the old narrative of world history is invalid. We need to explore it in order to understand how these injustices happened in the first place. But we also need to take a critical view and remember that the traditional narrative is just one of many ways of telling history. This particular way was thought up by Europeans and it views the world from a Eurocentric perspective.

In this book, we won’t just be talking about women; putting the women back in doesn’t mean we have to push the men out. Neither will we be able to talk about all the strong, clever, brave women in history, even if they were great leaders, philosophers and artists (often in the face of great adversity). To focus exclusively on women would result in a different book, a ‘History of the World’s Women’. That would be interesting, but it would be a specialised, niche perspective on history. Our aim instead is to put the women back into a global history that concerns all of us.

AFRICA AND THEN THE WORLD

PREHISTORY

Lucy

The Earth is around 4.6 billion years old. We don’t know for certain how the continents, mountains and forests, and the rivers, lakes and oceans, came into being or how life began, but we do have a few theories.

According to one of these theories, there was a beginning, and during this beginning, the universe and all its planets were created. We call this the Big Bang – even though nothing actually exploded. The name ‘Big Bang’ instead describes a time when the solar system and planets were completely different to what they are today. This beginning may have happened a very long time ago – billions of years ago, in fact – when our universe, made up of matter, space and time, was concentrated in just one small, dense point called a ‘singularity’. The universe then started to expand. Billions of years later, water appeared on Earth, possibly from comets, and slowly life began to develop. From simple self-replicating molecules, a growing diversity of life evolved in the oceans and on the land.

Around 200,000 years ago: The first Homo sapiens evolve.

There are many opinions about how and when the age of modern humans (Homo sapiens) began. Some scientists believe that these two-legged hunters, thinkers and fire-makers have been around for 2 or 3 million years. Others think that the first people who could really be compared to Homo sapiens, us modern humans, only evolved as recently as 200,000 years ago. The difference between these two figures is huge, but either way, the numbers are pretty mind-blowing. In fact, the history we actually know something about is relatively short – just 5,000 years. A blink of an eye when you think about how long the Earth has been around for!

Human history begins in Africa. Around 5–8 million years ago, there was another species of human living there. The word ‘human’ describes an ape that, unlike some other primates, walks upright on two legs and has an opposable thumb that can be used with the fingers to pick things up (a bit like tweezers). It’s thought that these apes first learned to walk when the forests they inhabited started to thin, meaning they were no longer able to swing from tree to tree.

Around 3.2 million years ago: The proto-human ‘Lucy’ walks the Earth.

In 1974, researchers in Africa discovered around fifty bones, clearly from the same skeleton. Most believe the skeleton to be that of a woman who is roughly 3.2 million years old. While analysing the skeleton, the researchers were listening to the Beatles song ‘Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds’, so they decided to call her Lucy. A few years ago, it was discovered that Lucy may have died after falling from a tree.

Between 8 and 2.5 million years ago, hominin brains changed drastically, bringing them one step closer to the ancestors of modern humans. They became more skilled, learned to speak and made plans. At some point, they discovered fire for the first time and used it to warm themselves and cook meat. They fashioned stone tools that made it easier to hunt and prepare food. Later, they used wood to make the very first houses. These were ground-breaking developments! As humans began to make things by hand, this was the start of civilisation and culture – things that are created by humans, as opposed to nature, which exists regardless of humans. One branch, the Neanderthals, evolved in Asia and Europe quite early on, but later went extinct.

Eventually, Homo sapiens – Latin for ‘wise man’ – evolved: a hominin species much more like modern humans. It wasn’t until 100,000 years ago or so that humans started to migrate from Africa to other parts of the world, including the Middle East, India, Asia, Australasia and Europe. Lastly, they arrived in America from Siberia via Alaska and continued their journey southward down the continent.

Men hunt, women chat

Around 2.6 million years ago: Humans start making stone tools. This is the beginning of the Stone Age.

For a long time, people imagined that life in the Stone Age was organised more or less the same as it was 50 or 100 years ago. Sure, there wouldn’t have been any cities, streets or houses yet, but it was presumed that humans divided labour the way they still did up until a few decades ago. Men provided for the family and women stayed at home by the stove cooking; it’s why so many museums and textbooks show pictures of men hunting. The men lie in wait for their prey (large or small, it doesn’t matter), kill it and take it home for dinner. The women, meanwhile, are shown gathered round the fire in a cave or a tent, crafting, or stirring a big pot suspended over the flames.

Some people argue that millennia of spending so much time together at the camp has made women chatty, while men would have needed to concentrate on silently stalking their prey, and that this has remained the case ever since. They say that, despite all the advances made over the past millennia, we still behave like prehistoric humans.

But we shouldn’t assume anything. Nobody can prove that life 50,000 or 100,000 years ago was organised along the same lines as today. Archaeological finds can only tell us so much.

Prehistoric vases showing figures in long robes have also been found. These robes are triangular and look just like skirts. There was no doubt about it, people thought: the figures on the vase must be women. Later, though, the same robes were found on painted figures who definitely had beards. It turned out that the skirted figures were, in fact, men. Archaeologists started to take a closer look and discovered more and more objects that didn’t quite fit the ‘men hunt and women chat’ pattern. For example, some women were found buried with weapons and tools, while some men were buried with beads and distaffs for spinning thread. Could it be that women were able to carry weapons – and use them? And that there were men who made their living from making textiles, even though we tend to see spinning and weaving as typically female activities?

The great mother

Around 29,500 years ago: The Venus of Willendorf is made, one of many female statues from the Stone Age.

Aside from vases and other items found in graves, many other archaeological finds help us form a picture of the Stone Age. These finds include cave paintings and small figures made from limestone, mammoth ivory, clay (back then, people had already discovered how to fire clay to make ceramics). One of these figurines is a limestone statue of a curvaceous woman, measuring just 11 centimetres tall. Archaeologists named it ‘the Venus of Willendorf’, after the small town in Austria where it was found. When the first of these small figures was discovered, they were named ‘Venus figurines’ after the Roman goddess of love. Today some archaeologists prefer to call them ‘female statuettes’ as the name ‘Venus’ is a little misleading: the figurines don’t actually have an awful lot in common with the Roman goddess at all.

What puzzled the researchers, though, was that similar statuettes had been found all over Europe, from France to Russia – even as far as Siberia. They quickly came to the conclusion that the figurines were representations of goddesses and a sign of common religious beliefs among the people who lived in the vast expanse between France and Siberia. The statuettes’ decidedly swollen stomachs could easily be a symbol of pregnancy, they explained later, so it was entirely logical that humans prayed to a female deity when they still lived a very precarious life out in the wild. It was woman who brought forth life from their bodies, just as the Earth brought forth all life and gave humans their food.

People saw a close connection between women and the Earth or nature: in many languages they still are referred to as ‘Mother Earth’ or ‘Mother Nature’. These statuettes, they believed, were depictions of fertility goddesses. But given that the Venus of Willendorf and other similar statues are around 30,000 years old, we will probably never have a definitive explanation. For instance, how do we explain the figurine found at Dolní Věstonice in the Czech Republic, whose facial characteristics match those of a woman found buried nearby? Could this mean that Stone Age humans made images of living people, as well as goddesses?

Whether men hunted, women sat chatting or goddesses gave life, we know very little for sure about the structure of early human society. There’s no concrete evidence, and no matter how much we’d like to describe the relationships between men and women, young and old, we can’t. An exhibition in a Swiss museum once featured a picture of a young prehistoric girl killing a hare. And why not? Perhaps girls did go hunting 10,000 years ago.

The Neolithic Revolution

Around 5,000 years ago: Humans settle and build the first cities.

At some point in history, hunters and gatherers began to settle. They built permanent homes, cultivated the land and founded villages and towns. Some say this process was the biggest change in the history of humanity. Because it took place during the ‘new’ Stone Age, or the Neolithic period, it became known as the ‘Neolithic Revolution’.

This revolution started almost 20,000 years ago. The biggest change of the Neolithic Revolution was the food people ate: growing crops like wheat, rice and millet rather than foraging for food in the wild meant people could settle in one place. Hunters and gatherers became farmers and herders; their diet of wild fruit and game was supplemented by bread made from the wheat they grew and the meat of the cattle they reared. They could produce larger quantities of food, so they shared tasks across the community and started trading with one another.

Then came the next major step: the discovery of copper, which could be used for making metal tools. These tools were much better than unwieldy stone tools. Copper was followed by metals such as iron and bronze, which gave their names to two archaeological eras, the Iron Age and the Bronze Age.

If you wanted to bake bread and raise cattle you needed land, and at times you would need to defend that land from others. For this you needed weapons and warriors. Some believe the distribution of these tasks also changed the relationship between men and women. Suddenly, one was in charge and the other was left with nothing.

Around 5,000 years ago, larger cities and kingdoms sprang up in some parts of the world, such as North Africa, the Middle East and India. These were highly sophisticated societies and civilisations. We don’t know why the first advanced civilisations appeared in these particular regions, while in other parts of the world it took 2,000 years for humans to leave their caves.

In these advanced cities and states, the relationships of power between people became more complex. Work wasn’t distributed equally: the building of mighty palaces and temples relied on a small number of master builders, who could calculate and plan, and hundreds of thousands of slaves, who did the heavy labour. This is worth remembering: when we talk about history, we’re usually talking about a small handful of powerful individuals and their advisers and assistants. These small groups ruled over most of the population. And at almost all times, life in these societies and their great achievements were built on the shoulders of oppressed, exploited slaves.

Around 3100 BC: The Sumerians invent the cuneiform writing script.

The complicated structure of the cities made another invention necessary: writing. Writing was more than just a practical way of dealing with everyday things such as organising the distribution of grain; it also helped people communicate with one another over large distances. ‘Send some wool along with the money. It’s too expensive here in the city,’ an Assyrian businesswoman once wrote to her husband who was away on a merchant trip. The letter was written almost 4,000 years ago.

Because writing conquers both physical distance and time, we can still read the Assyrian businesswoman’s letter today. The written word can survive for centuries, and eventually the world’s first historians appeared on the scene – people who consciously documented their experiences for future generations.

IN MESOPOTAMIA

SUMERIANS AND BABYLONIANS

Being first is what counts

Being the second or third person on the Moon isn’t quite the same as being the first. It’s the first person whose name is recorded in the history books; the first is the one we remember.

The first person on the Moon was Neil Armstrong and he was American. The first person ever to go to space was a Russian named Yuri Gagarin, and the first dog in space was Laika, who was also Russian (and female, no less!). As it happens, many of the world’s first astronauts were Russian, as was the first female astronaut, Valentina Tereshkova. Her expedition was really something special, as for a long time, few women had had the opportunity to do these kinds of things. It was the men who went to war, became politicians, played football or travelled to space. But why was that and when did it all begin?

When we tell history, we’re usually interested in firsts: when and where something happened for the first time. When we tell the history of the world, the events we view as important are the ones that have made the world what it is today. That’s why we find the Romans so interesting: they invented laws that are still in use now. Or the Chinese, because their invention of paper and gunpowder changed the world.

Big changes in the way humans lived were almost always connected to new inventions. Astronauts couldn’t have travelled into space without the help of complicated, innovative – and astronomically expensive – equipment. For eons, travelling to the Moon seemed like nothing more than a far-fetched dream, and it would take roughly 5,000 years for humanity to make that crazy dream a reality. Valentina Tereshkova, Neil Armstrong and Yuri Gagarin were the first to see our planet from a distance, looking back at the Earth from the Moon. Today we send satellites into space that can take photos of the minutest of details, such as roads and houses. The view of the Earth from the skies is now something we take for granted.

Of stars and gods

Things were the other way around 5,000 years ago. Humans looked to the heavens and observed the stars: they worked out that the planets appeared in the sky at regular intervals, in exactly the same positions. This got them thinking. As on Earth, events in the heavens seemed to follow a certain order. But if there was order, mustn’t there also be someone creating that order? How did the sun rise and set with such fixed regularity from one day to the next? How did the seasons change? Where did life come from and where did it go? What was behind all of this; what brought about this order? In other words, what was it that held the world together?

Humans searched everywhere for an answer. Eventually, they found one that was both simple and complicated at the same time: ‘God’. It was God who had created the world and held it all together. But now things got complicated: who or what was this God? Were they living? And were they male or female? Were there lots of similar beings who were all responsible for different things? Not one god but many? Or maybe God was something more abstract, like ‘nothingness’ or ‘eternity’? One thing’s for certain, though: since time immemorial, people conceived of gods and spirits who determined their fate. All over the world, people imagined them differently and called them by different names.

Back in prehistory, people believed that the gods lived in nature itself. They believed that a divine being with magical powers lived in every tree and river. When the weather god was angry, he lashed out with thunder and lightning. A raging god of the sea roused the oceans into towering waves. Invisible powers could take their revenge by sending a flood. To keep the gods happy, people made sacrificial offerings to them and communicated with them through song and prayer. Out of these rituals came religions.

But people eventually stopped believing in magical beings that lived in the natural world around them. They began using the fields, rivers and forests for their own benefit and the gods retreated from nature. If the gods had a home anywhere, the sky seemed the most likely bet.

The astrologers

The people of Mesopotamia, a region that roughly corresponds with modern-day Iraq, viewed their kings and queens as immortal beings who lived on as gods after dying. To prepare them for life on the other side, Mesopotamian rulers were lavished with gifts after death – inside Queen Puabi’s tomb, for example, archaeologists found a cloak decorated with more than 1,600 beads and a headdress made from around 8 metres of gold ribbon. Of course, a queen couldn’t be expected to travel to the world of the gods without a staff of female attendants, so ten slaves were buried with her, as well as a carriage and two oxen with harnesses.

Around 3100 BC: The Sumerians build the world’s first city states.

Puabi was the Queen of the Sumerians, who lived in the region that is now Iraq and which the Ancient Greeks called Mesopotamia (literally, ‘between two rivers’ as it’s between the Euphrates and the Tigris). The Sumerians built a sophisticated system of canals, which they used to irrigate large areas of farmland. They founded the cities of Uruk and Ur, where they erected great temples and distributed their harvests. To keep track of their finances, the Sumerians invented cuneiform, a form of writing based on a system of triangles and lines, which was etched into tablets made of soft clay.

Around 1850 BC: The Epic of Gilgamesh is written.

To break up the endless cycle of day and night, and to measure the passage of time, the Sumerians invented the seven-day week. They also invented a recipe for beer and whiled away the hours with board games and stories, which were important for creating a link between the past, present and future. In fact, the Sumerians also gave us the world’s oldest book, a collection of stories called the Epic of Gilgamesh. One of these stories tells of a mighty flood that once devastated the land.

The Sumerians believed that the moon god Nanna watched over Ur and the sky god An (or Anu) watched over Uruk. In each city, they built huge towers in the gods’ honour. These towers had a distinctive structure, built in tiers or terraces, with the temple itself placed at the top.

The gods’ protection couldn’t stop the Sumerian culture from collapsing eventually, but this end was far off.

Around 2270 BC: The Sumerian high priestess Enheduanna composes religious texts.

Until then, a long line of kings reigned successfully over the region. One of these kings, Sargon, married his daughter Enheduanna to the moon god Nanna, making her the high priestess of Ur. This wasn’t unusual: rulers all too happily had their daughters ordained high priestesses as a way of strengthening their power. Enheduanna was educated, and one of her tasks as priestess was to write hymns to be sung at the temple in honour of the gods. But Enheduanna was an unusually self-confident young woman. She clearly loved writing and began to write about personal things, such as pain and suffering, human emotions and her relationship with the gods. Although it wasn’t the custom at the time, she signed many of her writings in her own name. The phrase ‘I was the high priestess; I, Enheduanna’ seems to have been as important to her as serving the gods. Perhaps her confidence wasn’t entirely misplaced. As it turns out, she would become history’s earliest female author – or at least, her writings are the oldest we’re still able to read.

Of law and order

After the Sumerians came the Babylonians. They precisely recorded the movements of the stars and gave the constellations the names we still use today, such as ‘The Plough’, ‘The Scales’ (Libra), ‘The Lion’ (Leo) and ‘The Archer’ (Sagittarius). The Babylonians were convinced that the movements of the planets could be used to tell the future. From this they invented astrology: the belief that events on Earth are affected by events in the heavens – in other words, they thought our fate was influenced by the movement of the stars.

1792 BC: King Hammurabi comes to the throne of the Ancient Babylonian Empire. His laws – the Code of Hammurabi – were carved into stone.

For all their stargazing, the Babylonians didn’t neglect more earthly affairs. One of their kings, King Hammurabi, wrote down a legal code dictating how society should function: ‘An eye for an eye, and a tooth for a tooth.’ Hammurabi had these laws chiselled in stone and placed in the inner courtyards of the temples, so they could be accessed by anyone at any time. According to one of the laws on women, ‘If a “sister of a god” opens a tavern or enters a tavern to drink, this woman shall be burned to death’. A ‘sister of a god’ may have been a woman with religious duties. Clearly those duties were so important, the women were expected to behave themselves and not waste their time in the pub!

More than 3000 years ago: Assyrian law requires women to wear a veil. This is the oldest evidence we have of men and women being treated differently.

More than 3,000 years ago, the veil, a piece of fabric that courts controversy to this day, made its first appearance in history. According to Assyrian law, women and girls had to cover their faces in public; it was meant to protect them and showed men they were respectable. For slaves and servants, however, wearing the veil was a punishable offence: these women weren’t viewed as respectable and their bare heads told men they could be harassed without fear of punishment.

Rather than forbidding men from harassing women, Assyrian law demanded that some women protect themselves while denying others, the ‘disrespectable’, the same right. For men, there were no such rules. The veil is possibly the oldest visible sign that many societies treated men and women differently – and, almost without exception, women were treated worse.

FROM MESOPOTAMIA TO EGYPT

THE KINGDOM ON THE NILE

The Nile measures time

When we think of history, it’s tempting to think of a chronology of events. We might picture it as a timeline of dates running from left to right. But when we come to tell the stories of history, we find things can be more complicated. Important events often take place in lots of different places at once, so we end up having to draw lots of timelines in parallel with one another, with other connecting lines running across them, joining them up in an endless web. But in this book, we don’t want to present history as a jumbled web of criss-crossing lines – we want to tell it in words and stories. And that means we’re going to have to jump backwards and forwards a bit between places and time.

In several regions of the world, such as Mesopotamia, Egypt, India and China, history got going in several different places, at around about the same time. It always happened by a river: the land along river banks was especially fertile, so people were able to grow crops there, such as wheat and millet. Very soon, they began using the rivers and their tributaries as roads. Goods and heavy objects, such as the stones for houses and palaces, could be transported along them much more easily than over land.

The kingdoms between the Euphrates and Tigris rivers – Sumer, Babylonia and Assyria – ebbed and flowed, but their neighbour Egypt endured for an unimaginably long time. The Egyptian kingdom also had its beginnings more than 5,000 years ago, but unlike most of the others, it survived practically unchanged for more than 3,000 years.

Egypt owed its prosperity to the mighty Nile, a river almost 7,000 kilometres in length. The people of Egypt worshipped it like a god and sang songs to it: ‘Hail to you, O Nile, sprung from earth, come to nourish Egypt!’

When the Nile flooded, the earth transformed into a fertile black mud the Egyptians called kemet or ‘black land’. The land beyond the water’s reach was called ‘red land’ or desheret: desert.

For the Egyptians, the Nile offered persuasive evidence that nature was governed by a god-given order. Like clockwork, the river flooded every 365 days. When the Egyptians realised this, they invented a calendar. In this calendar, the 365 days between each flood were divided into twelve moons of thirty days each. This was roughly the time between each full moon. After these twelve months, there were still five days left over. These days were divided between the months and became festivals in honour of the gods responsible for maintaining this orderly structure. With the help of the Moon and the Nile, the Egyptians produced a calendar almost as accurate as the one we use today.

Houses for the afterlife

Around 2700 BC: The first pyramids are built in Egypt.

Perhaps the best way of understanding Ancient Egypt is through its pyramids, mortuary temples and tombs. The Egyptians believed that they didn’t stop existing after death; instead they crossed over into the afterlife, and they needed a house to live in once they got there. The Egyptians placed more importance on the afterlife than their fleeting time on Earth, so lots of care was put into furnishing these houses. These were the pyramids.

The rooms inside the tombs were spacious, linked together by long passageways and equipped with large larders for storing food, drink (mostly wine and beer) and a variety of household objects. Other rooms were fitted out with furniture, and those who could afford it took not only clothes, but jewellery, gold and silver on the journey. Every tomb contained ushabtis: small figurines made from wood, stone or ceramic that would do all the deceased person’s chores in the afterlife.

The Egyptians needed a body in the afterlife, so before the corpse was placed in its sarcophagus, it was embalmed and wrapped in linen cloth. Through this process the body was preserved, producing Egypt’s famous mummies. Before the body was preserved, the internal organs were removed and placed in special (canopic) jars. This was because the Egyptians believed that the heart was the source of all human thoughts and feelings. The brain, on the other hand, was considered useless. After death, it was simply removed through the nose and thrown away.

The walls inside the pyramids were decorated with hunting murals and scenes of the pharaoh and his priests conducting rituals in honour of the gods. Others show priestesses at great festivals, singing and dancing. Then, of course, there are the hieroglyphics, which were carved into stone and wet clay. Thanks to Egypt’s warm, dry climate and the fact that the tombs were well hidden away, the hieroglyphics have been amazingly well preserved.

These labyrinthine burial chambers offer us a snapshot of life in the past. These everyday objects needed for the afterlife – the jewellery, luxuries, vases and clay pots – all give us a deep insight into how people really lived back then.

This life

Before entering the afterlife, most Egyptians worked as farmers. But Egypt couldn’t have gained its reputation as an advanced civilisation if it wasn’t for its stonemasons, shipbuilders, joiners, painters and goldsmiths. One of the most well-respected professions in all of Egypt was the scribe. Scribes made long lists of the harvests and goods to be distributed among the people, wrote hymns and prayers to the gods, wrote biographies of the king and recorded the laws that helped everyone live in harmony.

5th century BC: The Greek historian Herodotus travels to Egypt and is amazed by what he sees.

Upon returning from his travels to Egypt, the Greek historian Herodotus told his fellow Greeks about an upside-down world:

Their manners and customs are the reverse of other peoples in almost every way. Egyptian women go to the market to trade, while the men stay at home and weave.

Herodotus was amazed that the streets of Egypt’s cities were bustling with women, doing all manner of activities. Egypt’s laws gave rights to women that were unknown among other civilisations at the time. Women were allowed to run their own businesses and own and sell land, and when they got married, they could keep everything their parents left them. If a case went to court, women could be called as witnesses just like men and could even represent themselves.

Despite all this, we must remember that everyday life in Egypt was often just the same as in other parts of the world. The men went to work, and the women stayed at home, especially if they were mothers. The Egyptians viewed motherhood as a miracle and childbirth was seen as one of life’s key events. There was another reason for this belief: everybody needed offspring who would look after them when they made their own journey to the afterlife.

The realm of the gods

After death, in the peace of the tomb, the gods were especially close. What could be more important than that? The gods permeated every aspect of the world. The Egyptians viewed everything as holy, and all that they saw, felt, tasted and heard had a divine origin. Atum the creator god had created the world from nothingness, the primeval ocean. The harmony of the universe was ensured by maat, the divine order. Instead of being permanent and unchanging, the world was defined by change – this meant that maat was constantly threatened by isfet, chaos.

When the gods appeared on Earth, they took on many different forms. Instead of ‘Mother Earth’, the Egyptians saw the Earth as a male god called Geb. In this respect, Herodotus’s description of Egypt as an upside-down world wasn’t too far off the mark. Geb’s counterpart was the goddess of the sky, Nut. She was believed to bend over the Earth and swallow the sun in the evenings, pitching the world into darkness, and in the morning, she spat the ball of fire back out. Some gods took the form of animals or were half-human, half-animal, like Thoth, who had the head of an ibis and was the scribe of the gods, or Anubis, who had the head of a dog or jackal and accompanied people to the afterlife. The goddesses Opet, a hippopotamus, and Heket, a frog, helped women in childbirth.

The realm of the kings

The pharaoh was both human and god. His spouse, the Great Royal Wife, was also seen as a divine messenger. The pharaohs were responsible for the divine order; to keep this intact, the royal couple was expected to produce a son as their successor. However, sometimes, the couple was unable to have children, or their children got sick and died prematurely. And sometimes when the king died, his son – the heir to the throne – was just a baby, and a bit too young to be responsible for maat, the divine order of the universe.

This is how Queen Hatshepsut came to the throne. As the Great Royal Wife of the deceased king, she ruled as regent on behalf of her nephew, who would be king when he came of age. Hatshepsut has been the subject of much debate, as by the time her nephew Thutmose III was old enough to rule, she had consolidated her power to such an extent that they ruled side by side, as two monarchs. However, because there were two of them, nobody knew what word to use to address ‘the king’ at official events, so the word ‘pharaoh’, meaning ‘great house’ or ‘palace’, was used instead. In other words, it was through Hatshepsut and Thutmose’s unusual form of joint leadership that all of Egypt’s kings came to be called ‘pharaoh’.

To strengthen her claim, Hatshepsut portrayed herself as both a man and a woman. Some inscriptions read: ‘The King of Upper and Lower Egypt that you wanted … beloved of the gods.’ In some portraits she was given male characteristics, in others, female.

Hatshepsut was a successful ruler: she established trade links with Egypt’s neighbours, made the country wealthy and constructed awe-inspiring buildings all over the land. The architect Senenmut was one of her closest confidants and tutor to her daughter Neferure, and there are many depictions showing the two together. In Karnak, one of the main temple complexes of the age, she had two enormous obelisks built and a wonderful barque shrine that housed a sailing boat she would need for the journey to the afterlife. Her mortuary temple was something special too, with three terraces that seemed to grow out of the cliff face. This structure sets it apart from the more famous pyramids that, by Hatshepsut’s time, had long gone out of fashion. Her mortuary temple is decorated with a large relief depicting scenes from her expedition to the Land of Punt, an ancient kingdom to the south of Egypt. Early in her reign, she and the royal household had travelled to this distant, mysterious land, which supplied Egypt with gold, perfumed resins and incense, cedarwood and lots of other raw materials.

Although Hatshepsut was a good ruler, after her death, the Egyptians argued about whether, by sitting on the throne rather than standing beside it, Hatshepsut had threatened the very order she was meant to protect. For a long time, it was believed that her nephew Thutmose had destroyed many images of her out of hatred. Lately, though, historians have suggested that his aim may have been to make people forget that a woman had been monarch. The images of her that remain intact are mainly those commemorating Hatshepsut as a person rather than as ‘the king’.

About 100 years after Hatshepsut’s rule, Amenhotep IV became pharaoh. He pushed back against the established order much more strongly than any female ruler of Egypt had ever done. Amenhotep IV did something completely outrageous: instead of upholding maat and appeasing the gods, as was his duty, he banned all gods. He asserted that there was only one god, the sun god Aten, and Amenhotep wanted to found his own new religion around this god. He gave himself the title Akhenaten, which means ‘the servant of Aten’.

Akhenaten’s desire for a new religion may sound harmless, but it was in fact an act of violence. He sent stonemasons all over Egypt to chisel the names of the gods from all the temples and obelisks. For many Egyptians, this was the malicious destruction of all that was holy and gave their lives meaning; they protested, but Akhenaten was unfazed and went on to develop a new alphabet and build a new capital dedicated solely to the worship of Aten.

Why Akhenaten chose to wage war against such a successful way of life and destroy its colourful pantheon of gods in favour of one single god remains a mystery.

This wasn’t the only mystery surrounding the self-proclaimed sun king. His rule might have been dismissed as nothing more than a mad episode in history if it hadn’t been for his charismatic wife. Her name was Nefertiti, which translates to ‘the beautiful one has come’. She stayed close to her husband’s side and was proclaimed the daughter of Aten. In this new cult, she had an important role, as it was through her alone that people could access the sun god. Akhenaten and Nefertiti were a radiant couple and some pictures even give the impression that Nefertiti herself is on the throne, with Akhenaten by her side, the position traditionally taken by the pharaoh’s wife.

However, it seems that Nefertiti died suddenly. She may have died after falling from a carriage, as the mummy some presume to be Nefertiti has serious injuries to its face and chest. Others say that the injured mummy isn’t Nefertiti at all, so we don’t know when and how she died. Recently another archaeologist has claimed to have found her tomb somewhere else.

To this day, it’s still unclear whether Nefertiti did indeed die a sudden death or whether she simply disappeared, which adds to the general aura of mystery around her. One thing is certain, though: with her disappearance, the magic surrounding the royal couple disappeared too.

Akhenaten had tried to use violence to introduce a religion focused on one god. However, his son Tutankhamen brought back the old gods, and with them, stability. The new pharaohs left Akhenaten’s city and his palace returned to dust under the Egyptian sun. The Egyptian empire itself would survive another 2,000 years.

Egypt’s neighbours: the kingdom of Kush

From around 8 BC to around AD 350: The kingdom of Kush emerges south of Egypt.

Most of Egypt’s resources, especially gold and slaves, came from Nubia, a region in the south where the Blue Nile and White Nile merged together into one colossal river. The local people, the Nubians, looked different to the Egyptians and had darker skin. Eventually, a Nubian prince successfully founded a state that was independent from Egypt. This kingdom was known as Kush; here the ruler could now build his own temples, palaces and tombs. The Kushites worshipped the Egyptian gods but had their own alphabet, which has been deciphered but remains untranslated to this day. They also built pyramids at a time when they were no longer being built in Egypt. The Kushite city of Meroë is located in modern-day Sudan and is home to the largest group of pyramids anywhere in the world.

During the Kushite era the city of Meroë became the new seat of government. Over the years that followed, the reins of power were handed down to a succession of Kushite queens. Some ruled alone, but even the married ones were extremely influential; they were both mothers and warriors, and may even have taken on the role of priests, as suggested by an image of Queen Amanishakheto. In this image, the queen is dressed in a leopard skin – something usually worn exclusively by priests.

FROM EGYPT TO INDIA

HISTORY BEGINS IN THE INDUS VALLEY

Harappa and Mohenjo-Daro

When you look at a map of the world, the region in the Middle East that was home to the Sumerians, Babylonians, Egyptians and Jews is a relatively small area. East of Mesopotamia, beyond the Persian Gulf, there’s a great river. This river is called the Indus, and today it forms the gateway to its namesake country: India. Along the banks of the Indus, researchers have found traces of an advanced civilisation, almost as old as Sumer.

We know very little about the scale of this civilisation, but it’s thought that it may have covered an area larger than all the other early civilisations put together. It’s possible too that the world’s oldest written records came from here.

2600–1900 BC: Ground-breaking technological discoveries are made by the Indus Valley’s Harappa culture.