9,59 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Luath Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Serie: Viewpoints

- Sprache: Englisch

The history of parliament in the UK has a consistent theme: the refusal to accept any binding contract with the people. This unacceptable status quo goes for Holyrood as much as for Westminster. The time has come for people to challenge the power of the ruling class. We want to see the Scottish Parliament become an institution that it has so far failed to be: an institution committed to the sovereignty of the people. We want the people of Scotland to lead the rest of the UK by example, and ensure that the actions of a government are bound by shared political and ethical values. And we propose the first step: a modest proposal, for the agreement of the people. Are you with us? 'ANGUS REID and MARY DAVIS We need a common ground, and this is a brave attempt to create that in simple and universal language … DAVE MOXHAM, Deputy General Secretary, STUCT This fascinating project has the seed of revolution in it … GEORGE GUNN, writer and broadcaster CONTENTS Prologue Call for a Constitution Introduction CHAPTER 1 The Words CHAPTER 2 The Journey Map Responses Schools CHAPTER 3 The Past The English Revolution, 1647 to 1649 The Workers' Story, 1910 to 1918 For Women, 1914 to the present day CHAPTER 4 Considering a Constitution A socialist view A view from a former Government insider A view from Iceland A view from the Red Paper Collective A view across the Meadows CHAPTER 5 Epilogue: The White Paper Acknowledgements Contributors Bibliography Petition

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 226

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Ähnliche

A Modest Proposal

for the agreement of the peoplelaying out terms by which governments can be bound to act ethically and equitably in the interest of those they represent.

Luath Press is an independently owned and managed book publishing company based in Scotland, and is not aligned to any political party or grouping.Viewpointsis an occasional series exploring issues of current and future relevance.

In 2012 and 2013 Angus Reid toured Scotland, leading a discussion, and placing the words of his ‘Call for a Constitution’ on many public walls, including the STUC and the Scottish Parliament. He found eager listeners and a hunger for change.

This book has grown from that project to embrace the compelling history of the struggle for civil rights in the UK, and contributions from Scotland, the UK and abroad.

It lays down a challenge to people and parliamentarians alike.

A Modest Proposal

for the agreement of the people

ANGUS REID|MARY DAVIS and many others

LuathPress Limited

EDINBURGH

www.luath.co.uk

for all those that show their supportpast, present and futureand especially Mike and Sheila Forbes

First published 2014

ISBN (print): 978-1-910021-05-7

ISBN (eBook): 978-1-909912-89-2

The authors’ right to be identified as author of this work under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 has been asserted.

© Angus Reid and Mary Davis 2014

Contents

Prologue

Call for a Constitution

Introduction

CHAPTER 1 The Words

CHAPTER 2 The Journey

Map

Responses

Schools

CHAPTER 3 The Past

The English Revolution, 1647 to 1649

The Workers’ Story, 1910 to 1918

For Women, 1914 to the present day

CHAPTER 4 Considering a Constitution

A socialist view

A view from a former Government insider

A view from Iceland

A view from the Red Paper Collective

A view across the Meadows

CHAPTER 5 Epilogue: The White Paper

Acknowledgements

Contributors

Bibliography

Petition

Prologue

THE SOMEWHAT LONG title for this book expresses a new way to see and to measure the debate over the future of the UK, starting with Scotland. It seeks to go beyond the constitutionalimpasseand instead it looks back throughout our history, and forward to all those who have engaged with the words of the poem in the languages of the north – many of whom have left incisive comments about the words as they have appeared – as if by magic – in 22 places around Scotland. All this counts as a form of contemporary oral history and is therefore highly relevant to this debate.

So what is the significance of this wordy title and how does it illuminate the book’s content? Firstly, the title contains the essence of what we are striving for: an agreement of the people such as was negotiated in the 17th century. Secondly, the title captures the flavour of the pamphlet war in both the 17th and late 18th centuries, a tone that Jonathan Swift borrowed for his own purposes and did so without sharing the optimism, that we have, for a settlement that can embody genuine social change. Thirdly, we have used the words ‘modest proposal’ because that is how the Levellers1termed their own intervention in the constitutional debate; they even used the titleThe Moderatefor the broadsheet that articulated their views.

The purpose of this book is to make parliaments concede powers to people and to get on with the necessary democratisation of our society – to empower people and to take a step away from top-down authoritarianism. This characteristic of the present status quo would be just as true of an independent Scotland as currently foreseen. The future of Scotland and the UK is too big an issue to leave in the hands of parliamentarians: like all progressive change, it is going to take people power to make a just, ethical and equitable settlement. This has rarely been done in our long history, although it was attempted, as we shall see, during the English Revolution. On other occasions, the repressive apparatus of the state was simply too strong to permit any progressive breakthrough of people power and in any case, the people were often not sufficiently united to present a powerful enough alternative to the ruling status quo. This requires class unity, and a corresponding ability to transcend racism and sexism.

To seek ‘the Agreement of the People’ will once again begin the debate about what we mean by unity, and will, we hope, put flesh on the bones of what has for too long been a mere slogan.What kind of country do we want to live in?What kind of society is it that we all aspire to?We cannot achieve unity unless we know not just what we are against, but also what we are for. We call for an ethical and equitable society. We call for the Scottish parliament to debate the words, and then to put them to the people of Scotland. What we want is a commitment, and even though that would only be a first step, we want to make an irreversible step in the right direction that can serve as a leading example to the rest of the UK.

1 The Levellers were apolitical movementduring theEnglish Civil Warwhich called forpopular sovereignty, universalsuffrage,equality before the lawandreligious tolerance, all of which was expressed in the manifesto ‘Agreement of the People’. They came to prominence at the end of theFirst English Civil Warand were most influential before the start of theSecond Civil War. Leveller views and support were found throughout the country and particularly inLondonand in theNew Model Army.

Introduction

ANGUS REID AND MARY DAVIS

WHERE IS THE CONTRACT by which we agree to accept the authority of a government?

The absence of a written constitution in the UK leaves the vast majority of people at the mercy of an authoritarian parliamentary class that can threaten our civil rights and liberties according to political whim and by simple majority. The right of redress is remote and expensive. This goes for Scotland as much as it goes for the UK as whole. This unhappy status quo is defended by the idea that it is impossible to define our common values and common identity. This book challenges the laziness of that position. It proposes words to define that consent: words to bind governments, institutions and people into a common social contract. The aim of the words is to put people first, to define dimensions of human existence, and to propose that these values be paramount in any negotiation. We think they are fit for the 21st century: no other constitution in the world, for example, acknowledges our collective responsibility towards the planet.

This idea is aimed at the whole UK, but launched from Scotland because, in the run-up to the Independence Referendum in 2014 in Scotland, the hard carapace of state authority has momentarily softened and there is an opportunity to define a new and better country. The status quo cannot stay as it is, and the political parties are seeking to alter and amplify the powers of government. But where, amid all the political positioning, is there a voice for people?

A constitution must be framed by popular consent. It must originate outside politics, among people. How else could it represent them? A constitution is not an act of government; it is the act of a people constituting a government. The words of the poem are intended as a challenge both to people and to members of parliament by suggesting a form of words that can frame an ‘Agreement of the People’. Given such an agreement, the values, rights and responsibilities they embody must then be reflected in the laws, the institutions and the whole behaviour of civic society. This demand is not new: it is the form of the original ‘Agreement of the People’ laid out by the Peoples’ Army and presented to Oliver Cromwell in 1647 in Putney, when the term ‘constitution’ first entered the lexicon of British political history. And the Leveller contribution to the political tradition of the whole UK should not be underestimated. It was Leveller ideas that gave rise to the only popular uprisings in Scotland, in the South-West in the 1650s, that were lead by neither the nobility nor the clergy. This is the tradition of popular protest that is articulated in the work of Robert Burns.

The words that you can find at the beginning of this book reflect the need for people to have more say than yes or no; for people to define the kind of country they want to live in. They derive from discussions held over a number of years and represent a collective agreement. This book documents their public exposure in Scotland and the public response to them. As I put the words on the doors of Mike Forbes’ barn in Aberdeenshire his sister, bringing me a cup of tea on a cold March day, said: ‘…if only it were that simple…’ But… why can’t it be that simple? A people’s agreement is bound to have that virtue: to be simple, memorable and universal. Not to be, as so much political discourse is, partial, secretive and complex.

The way that communities have accepted them across the country raises the question: if communities and individuals can agree to be bound by these values, then why can’t their political representatives, and why can’t the parliament as a whole? If Mike and Sheila Forbes agree to these words, and their MSP – the First Minister himself – has also signed his agreement, then why can’t the parliament act on them?

In each location that they were installed they were accompanied by the invitation to leave a mark of agreement. It was a petition that was made simultaneously across Scotland and inside the Scottish Parliament and it attracted thousands of signatures, including those of Scottish Government ministers and the First Minister. Thereafter came a political manoeuvre by the Constitutional Commission. I was told that the words had been appended as a ‘preamble’ to a ‘draft constitution for an independent Scotland’, without my permission, and without telling me what that document was. I was dumbstruck: the words are not there to be added as decoration to a government document; they are there to place ethical values at the beginning of the process. They propose a system of values that a constitution must embody. However, it does indicate that the campaign has met with some success – it is visible – and has forced the government to show its hand as can be seen the recent announcement by the Scottish Government that an ‘interim written constitution’ will be published in the near future.1Naturally, this comes along with the coercive agenda that only a vote for independence will secure these rights. This is where our interests diverge. A constitution is not there to be used by a government as a carrot for a dumb population, but is the demand by that same dumb population to hold the government to account. Hence the need for this book: to show that we operate differently, and openly, and in public. We have nothing to hide. We ask that these words are not merely treated as a decorative addition to a putative constitution, but accepted for what they are: words that have widespread support. We ask that they be debated in a full session of parliament and then put to the people of Scotland at large. This would be a daring initiative. It would show that the government can accept that the ‘sovereign people’ are capable of expressing a voice, and that they are capable of listening to it and responding. To take this initiative would be to show that Scotland can seize the moment and lead the rest of the UK by example. Were that to happen, then whatever the outcome of the 2014 referendum, it’s a victory for democracy.

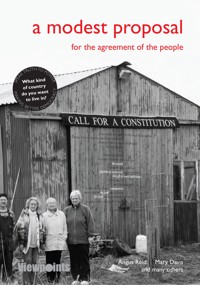

This book addresses itself, therefore, to the space in between the government and the population at large. That space is everywhere, in libraries, schools, streets, public buildings and private homes, and for the cover of the book it is represented symbolically by the barn at Menie, in the midst of that conflict between capital and community. There, people – ordinary people – find themselves with no effective rights as citizens, no faith in the decisions taken by authorities, and with no basis from which to negotiate. This is wrong. That conflict and that space are well known in Scotland, and it is one of many good places that the words have found a home. The cover of the book shows three women at Menie, and the text contains an essay warning women about the history of the past 100 years: 100 years of unfair treatment and discrimination. It’s also a reminder of the role of women – often completely hidden – in making significant social change. It is our experience that it is to women that these values appeal in particular, from the grandmother that left a handprint on the boards in Orkney with the simple statement ‘…care for the land’, to Sheila Forbes, the wife of Mike, who stands alongside him and others in resistance to Donald Trump in Aberdeenshire.

As the project has grown it has developed other dimensions, and in particular in terms of that social microcosm, the school community. The invitation to create a School Children’s’ Charter in two schools, in Edinburgh and Stranraer, has lead to a very significant challenge to the way that schools define their purpose and relationship to children. When the majority finds a voice and uses it to make a simple and direct statement, then it represents – naturally – a major challenge to the prevailing authority. Suddenly a whole community has a dilemma that can best be resolved by applying democracy. And so a whole school votes either for or against a poem, and the very action of voting and extending the suffrage to the whole school community is a great development. However, as you will see throughout this book, the habit of the powerful never to concede rights to the majority is reflected in this social experiment in schools, and the opportunity to democratise responsibility – which is present to us all in this moment – is being squandered. Let’s change that around.

This book is in five parts. The first explains the genesis of the words and gives them to you in the other languages of Scotland. Please read them. To see them written in those languages is amazing. The second follows the journey that the words have made around the country in the past 12 months. The aim was to introduce them into the background of many public places, from the Scottish Parliament to the humblest bus stop, from libraries and schools to public cinemas and private homes, and to invite signs of agreement – handprints. The words went up to sit quietly in public spaces and to make people think, and the book is here to give you something to do about it.

The third part, by Professor Mary Davis, the Labour historian, addresses the remarkable history we have in this country in fighting for social rights. In many ways the initial idea of a peoples’ democracy was created in Britain. Although it has often been crushed in the moments when that voice has asserted itself, that tradition lives on, and has had a profound affect on many countries and peoples throughout the world. This part aims to show you who your allies are if you fight for rights: from the Levellers, to the working classes, to women, and aims to inform you about the history of those struggles. If they are aimed at school children and teachers because they ought to be on the curriculum and are not, they are also aimed at the labour movement and anyone interested in progressive politics. This is a history of British radicalism, which it is essential to grasp, and to learn from.

The fourth part of this book looks beyond the present moment to a future in which we might all participate in the creation of a constitution. What would be the next step were the parliament to encourage the empowerment of people, and to abide by their voice? These five essays come from different quarters: from the labour lawyer John Hendy QC who presents a socialist view and explores how the rights of the working class need to be safeguarded by a defence of collective bargaining at the workplace and industrial level, and highlights the recent case of Grangemouth; from Alex Bell, who recently resigned as Head of Policy at the SNP and who admires the ‘crowd-sourced constitution’ as was tried recently in Iceland; from Professor Thorvaldor Gylfason who watched the Icelandic endeavour being destroyed by the factional interests of parliamentarians; from Pauline Bryan of the STUC based Red Paper Collective, that asks what constitutional powers should be for; that asks what constitutional powers should be for and proposes a new federalist model for the UK; and from one of the hosts of the poem in Edinburgh, Danny Zinkus, a member of Unlock Democracy who explores his own hopes for the project and considers how constitutional rights could change our political habits as a community and as a society. If we can take the first step, then many possibilities would open up, and these essays represent the beginning, and not the end of the debate about the kind of future that we can fashion for ourselves.

The last part of the book examines what the recent White Paper has to say about a future constitution and popular sovereignty.

The book also aims to introduce a new and a different tone to political debate, and to wear its independence from any party political agenda on its sleeve. We and the contributors to this book are not dry debaters or paid-up politicians, but artists, writers, polemicists, historians and activists who have reached out into different communities, landscapes, histories and ideas, breaking boundaries of age, race, language and gender, and also breaking down the border of political discourse between Scotland and the rest of the UK. This is a political book full of pictures and full of people: it aims to express itself differently to the run-of-the-mill fare in this corner of the market. Our intention is to allow the many voices, reactions and locations to speak up and to speak for themselves. Ultimately, this book is an invitation to inform yourself, and to agree, and to show it.

This book is a people’s contribution to the debate before the Referendum and we are not aligned with either the Yes or the No campaign. We take the view that any people anywhere who are governed without a constitution agreed by the people are governed by power without right. So can this be changed? In our view, the best future for the UK is as a federated state, and we do not support the version of independence that is on offer for Scotland. We see the open debate in Scotland as a rare and perhaps unique opportunity to make a giant step forward for civil rights that will affect the whole UK. As Eliott Bulmer, the thoughtful creator ofA Model Constitution for Scotland2points out, no sincere democrat could possibly support independence in the circumstances under which it is currently proposed. What appears to be on offer in the Scottish Referendum is a wholesale transfer of powers from Westminster to Holyrood and the creation of a supremely powerful parliament with no people’s constitution to constrain it. In which case it would, in Bulmer’s words, ‘only perpetuate the worst failings of the Westminster system, and … betray the democratic values which have for decades been central to Scotland’s grievance against the UK’.2This model of independence would create an excessively centralised parliament with no second chamber whose elite could do anything it wanted and, if history is any guide, that is most unlikely to concede any of its power to people. By being asked to vote ‘Yes’ we are being asked to participate as spectators in the creation of a new and unconstrainable ruling elite. This is no invitation to create a better democracy, and the choice offered between yes and no does not allow us to define the kind of country we wish to live in any meaningful way.

No. The constitution has to come from outside government if it is to reflect the principle of ‘the people’s sovereignty’. This is our position, and we take the view that no government has ‘power by right’, as Tom Paine put it, without a contract with the people. Later on in this book are a number of essays that reflect on what constitutions can do, what the powers are for, and how they can fail. These essays are there to hold the Scottish Government’s plans up to scrutiny.

InA Model Constitution for Scotland(p. 15) Bulmer outlines the various constitutions that have been part of the SNP’s thinking since the 1970s, none of which has sought to discover, to articulate or to represent the values we hold in common, and much less undertaken to be bound by clearly defined values and responsibilities. This is what we can do something about by getting them to debate and endorse this proposal. We hope to change the political landscape, and to change the way a person – any person – can be seen within that landscape. The old hierarchies, classes and ways of doing politics need to be turned upside-down. We call for an agreement of the people. We call for the empowerment of every citizen. We call for a constitution and this is the necessary first step towards it.

A modest proposal.

Are you with us?

Footnotes

1 24/03/14 http://news.scotland.gov.uk/News/Enshrining-Scotland-s-values-aa7.aspx

2 A Model Constitution for Scotland, Luath Press, 2011.

CHAPTER ONE

The Words

ANGUS REID,et al.

IN SCOTLAND WE CAN do something that has never been done before in the history of these islands. To write a social contract fit for our times has been done before but never endorsed peacefully and by majority consent. Were we to achieve this in Scotland we can show the rest of the UK that this is the best way forward.

The words in the poem came from discussions in England and Scotland, and these are quotations from an exchange of emails that followed up discussion with a group of ten in Edinburgh:

… It is a good idea for a country, as well as any other formally organised society, to have a set of basic laws from which other laws can be derived, and which are considered so important that no new law can contradict them…

… I like the idea of ‘grundgesetz’ – basic givens that underpin every other right, freedom and statement… As with the fundamental laws of physics (which are simple, absolute, universal and stable over time) there will be very few grundgesetz… I believe a Scottish Constitution should enshrine values and aspirations that all people everywhere agree on almost instinctively…

… I agree that law should reflect basic shared values. This can strengthen the authority of a constitution by making clear how specific laws follow from basic principles… an example is the principle from the German constitution ‘Eigentum verpflichtet’ (ownership obliges). This means that the state expects that owners accept the obligations that come with ownership. This is, for example, how we can justify that they take taxation from us because it defines the purposes to which it will be put…

… I feel that while protecting human rights has done a great deal of good to individuals and states, it has done immeasurable harm to the planet for it ignores the rights of every other living thing. If you believe in rights, then a habitable environment is surely the most fundamental right of all…

… We mentioned the protection of the environment and I think this was a very interesting point: the value of the environment has been recognised only recently and is not therefore part of most existing constitutions: neither those that date from the 18th century, nor the German one that dates from 1947… This is an area in which a Scottish constitution could be at the cutting edge of current social thought…

All these discussions took place seven years ago, and predate the SNP government and the 2014 Referendum. They address themselves to the whole country and to the fact that the status quo is neither acceptable nor stable:

… Without a written constitution there is hardly any protection of rights – any ad hoc parliamentary majority can instantly abolish all previous rights…

… The classical argument … that Britain already has a constitution that has evolved over centuries… defines a constitution so generally that any piece of written law can be interpreted as part of it, and the term is extended so far that it loses all meaning…

… The British idea of a constitution as a set of different laws with no hierarchy means that laws are in conflict with one another, leaving the field open to all kinds of arbitrary decisions…

… Those who want a truly radical and indeed workable solution to the malaise in our liberties should look to a British Bill of Rights embedded in a written constitution, applied by judges who – as in the United States – have the power to ensure that liberties won … are not abandoned by MPs…

Scotland has the chance to take the lead, but the government has gone about addressing this fundamental change in the wrong way. We should start by defining what kind of country we want to be, and what kind of responsibilities we have towards one another, and then let everything else flow from that. We should start with ground laws that are simple and universally known, and that, as Danny Zinkus says in his essay at the back of this book, that can live in everybody’s back pocket.

The poem – or ‘the words’ as they are known up in Aberdeenshire – propose a way to define those ground laws. To be precisely defined is important, and that is why they are proposed in the form of a poem. It is a kind of armoury that defends the words themselves, as a jeweller might set a precious stone.