Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Atlantic Books

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

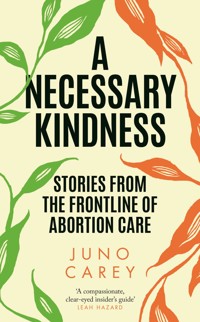

'A frank, comprehensive and often moving book... A powerful insider account that opens a door into a long-hidden world in which secrecy and shame have been weaponised against women for too long.' Observer 'An unflinching insight into the reality of abortion' Irish Independent In 2015, Juno Carey left her job as a midwife, burnt out, frustrated and looking for a better way to deliver care to women. And then she found work that she loves, that brings her satisfaction and the knowledge of helping women, directly and fundamentally, every day. Working in an abortion clinic is not easy, but it is a necessary kindness: Juno's work changes and even saves lives. In this book she shares the stories of the patients she helps there, young and old, single and married, vulnerable and stoical. She cares for women who are already mothers, women who have had to travel to the UK to get help and those who face unimaginable trauma. Urgent, illuminating and deeply human, A Necessary Kindness reveals the misunderstood world of abortion clinics, and deals with a complex issue - around which there is still too much taboo and too little understanding - with gentle compassion and bold conviction. These are the stories we need to share, the conversations we need to be having and the rights we need to protect.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 344

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

A Necessary Kindness

First published in hardback in Great Britain in 2024 by Atlantic Books,

an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright © Juno Carey, 2024

The moral right of Juno Carey to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

Every effort has been made to trace or contact all copyright holders. The publishers will be pleased to make good any omissions or rectify any mistakes brought to their attention at the earliest opportunity.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Hardback ISBN: 978 1 80546 041 1

Trade Paperback ISBN: 978 1 80546 042 8

E-book ISBN: 978 1 80546 043 5

Printed in Great Britain

Atlantic Books

An imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd

Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London

WC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

This book is dedicated to all of the brave women who seek help, and to all of those people brave enough to help them.

I believe that any experience, whatever its nature, has the inalienable right to be chronicled. There is no such thing as a lesser truth.

Annie Ernaux, Happening, translated by Tanya Leslie, 2019

None of this is invisible. You can see what’s real if you look.

Clair Wills, ‘Quickening, or How to Plot an Abortion’,London Review of Books, March 2023

Contents

Introduction

1. A Difficult Start

2. At Their Most Vulnerable

3. Close to Home

4. Anti-Choice

5. The Most Necessary

6. Pregnant People

7. The Worst Outcome

8. Unexpected

9. Less Than Ideal

10. Unprecedented

11. Aftermath

Afterword

Resource List

Notes

Acknowledgements

Author Note

The stories in the following pages come from my experiences and memories of working as a midwife and in abortion care, and from the women who I have encountered through this work. The identifying features of people and places have been changed in order to protect the privacy of patients and colleagues, and descriptions of certain individuals and situations have been merged to further protect identities. Any similarities are purely coincidental.

Introduction

I CAN SAY without hesitation that I love my job. I understand that my devotion to my work will come as a surprise to many. I first trained and worked as a midwife, and I loved that too. The journey that led me to my work at an abortion clinic was an unexpected one, but it is one that many midwives have made before me and since. The gap between helping women deliver babies and helping them terminate unwanted pregnancies no longer seems wide to me; it is a spectrum of reproductive care, and we need both, and much more. Now, more than ever, the stories of those who have had abortions, and the stories of those who provide them, need to be heard and understood.

On Friday 24 June 2022, the supreme court in the United States overturned the decades old Roe v. Wade decision, which had federally legalized abortion in America since 1973, paving the way for sweeping abortion bans all over the country that removed many people’s reproductive rights overnight. I read the news on my phone – the judgment had been leaked a week before but the dreaded confirmation had just been announced – as I sat in an IVF clinic reception, waiting to find out if I had been successful in conceiving my second child. ‘Holy shit,’ I whispered to myself, and my stomach dropped. I hadn’t really believed that it would go this far. I could instantly envisage the horror that my fellow workers in abortion care in the United States would be feeling but could only imagine the fear that women must be feeling. I knew what this would lead to. People who do not want to be pregnant will not simply accept being trapped by their bodies and forced to carry that pregnancy to term. They will make long and torturous journeys if they can afford them, and if they can’t, then they will find another way, one that could potentially kill them.

We are lucky to have access to abortion in the UK, but we should not assume that our reproductive rights are safe here. Contrary to the assumptions of many, there is no right to abortion codified in law in this country. In fact, abortion is still illegal here. Under the 1861 Offences Against the Person Act (OAPA) it is a crime to ‘procure a miscarriage’ or help another person to do so. This law remains in force to the present day. Treatment is facilitated only by the 1967 Abortion Act, which provides exemptions if certain conditions are met and if two doctors give their approval. But as long as the OAPA remains on the statute books, both doctors and patients face potential prosecution. And anti-abortion activists have shown their willingness to press for prosecutions if a practitioner does not correctly fill out the requisite paperwork. This is intended to have a ‘chilling’ effect on medical professionals taking part in abortion care, and there is some evidence to suggest that this is working. A study published in 2018 found that the threat of criminal sanction created an atmosphere of ‘fear and insecurity’ and one doctor interviewed for the study said that ‘All of the negative light that’s been shone on abortion … to see if doctors are breaking the law. I think those things are deterrents to junior doctors going into the field and wanting to get training.’1

Patients too are not protected, in law or in practice, from being prosecuted for having an abortion.

Since I started writing this book, prosecutions of women for procuring abortions, under the 1861 OAPA, has picked up pace in the UK. For context, and as a measure of how antiquated the law with which these women are being criminalized is, it also prohibits ‘destroying or damaging a building with gunpowder’ and ‘impeding a person endeavouring to save himself from a shipwreck’.

In June 2023 a woman was given a twenty-eight-month prison sentence for procuring drugs to induce an abortion after the pregnancy had progressed beyond the legal limit. She was ordered to serve half this sentence in custody, despite having other young children and the judge’s acknowledgement that she was racked by guilt and suffering depression. A letter to the judge signed by the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists and the Royal College of Midwives asked him not to give a custodial sentence in this case, as it would deter other women from seeking medical care for fear of prosecution. The judge called the letter ‘inappropriate’.2

In August 2023, a twenty-two-year-old woman was also put on trial for procuring an abortion and became the fourth woman that year to be prosecuted under the 1861 law. There were only three prosecutions in the more than 160 years prior to that.3 The fresh zeal with which these women are being pursued by the Crown Prosecution Service should ring alarm bells.

Abortion provision is, I believe, a normal health service that every civilized society offers to its citizens, so that they can exercise full autonomy over their bodies and their lives. We have seen the effects of hundreds of years of illegal, restricted or inaccessible abortion all over the world. These barriers lead to women suffering and dying from unsafe and unregulated illegal procedures, administered by themselves or by often unscrupulous physicians. In her memoir about her abortion in 1960s France, Annie Ernaux writes that ‘knowing that hundreds of other women had been through the same thing was a comfort to me’, but what she is referring to is a self-administered abortion with a long knitting needle. We know that, without other options, women have tried to end their pregnancies with coat hangers, by throwing themselves down flights of stairs or with dangerous quantities of illegal drugs.

One of the immediate effects of the 1967 Abortion Act, which legislated for abortion provision for the first time in England, Wales and Scotland, was to drastically reduce the number of deaths from unsafe abortions. In the decade immediately after the act was brought in, the proportion of maternal deaths due to abortion dropped from 25 per cent to 7 per cent. During 1961 to 1963, 160 deaths were recorded as due to abortion; during 1982 to 1984, there were 9.4 And in 2021 there were zero deaths from abortion in the UK.

In the ‘best case’ scenarios, women don’t acquire a lethal illegal abortion but are instead forced to carry their pregnancies to term, with all the life-changing and, in some cases, deeply traumatic consequences of that. But abortion care is an area of women’s rights and healthcare that is still dangerously taboo in this country, and around the world.

I have worked in several clinics over my career, in a major city and a rural town. I have been the first point of consultation for abortion patients, have worked in surgical recovery at the clinic and, in recent years, have worked remotely on the clinic’s aftercare phoneline. In my time as a midwife practitioner working in abortion clinics, I have seen that abortion involves many contradictions. One such contradiction is that, though it is portrayed as something extreme by its omnipresent opponents, it is actually incredibly common – far more so than I think most people realize, even the patients themselves. One in three women in the UK will have an abortion in their lifetime, and these figures are broadly similar across the world – depending on, of course, the restrictions on and accessibility of abortion provision in those countries. In the United States before Roe v. Wade was overturned, around one in four women would have a termination in their lifetime.

More people in this country will get an abortion than a tattoo (one in four), and more people will need treatment for an unwanted pregnancy than they will for hay fever (also one in four). But most likely you don’t know, or think you don’t know, anyone who has had an abortion. If you do, I wonder if they have spoken to you at length about that experience. If I didn’t work in abortion care, I don’t know if the women in my life who have had terminations would have told me. I wonder if it would have come up organically in conversation, or if they would have felt comfortable revealing it to me. These days we speak openly with our friends about losing our virginity or our experience of childbirth, and we can even joke darkly about STIs we have caught. But we have not been very good at facilitating conversations about abortion. And I see that reality every day in my consultation room. Women sitting opposite me who are scared, who are ashamed, and who imagine themselves to be almost entirely unique – and therefore alone – in going through this process. But they are not. If you have thirty women in your life – your friends and family, your colleagues and acquaintances – then you likely know ten people who have had or will have an abortion. Maybe you are one of them.

The void that we have created by failing to talk openly about abortion – who really has one and why – has been filled instead by those who oppose it. They have predominantly filled it with prejudice and misinformation, and in many areas of the world, their efforts are paying off. As we have seen, access to abortion has been dramatically curtailed in the United States, with many states drip-feeding increasingly draconian anti-abortion legislation through their systems, and there is currently no end in sight to the stripping away of reproductive rights there. Those rights are under siege in Europe too, with Poland – an EU member state – bringing in an almost total ban on abortions when its supreme court ruled that abortions for fetal abnormalities, which make up 98 per cent of terminations in the country, were unconstitutional.5

People should be aware that our rights are vulnerable here in the UK too. What is happening in other parts of the world could happen here, more easily than we may want to acknowledge. Well-funded and highly organized antiabortion groups, emboldened by their success in America, are turning their attention to the UK, pouring resources into efforts to roll back abortion access here too. We may think that it couldn’t happen to us; many people in the United States didn’t believe it could happen to them either.

We are proud to live in a free country, but women are not free until they are free from guilt and shame and free from the threat that their agency over their own bodies and their destinies can be taken away from them overnight. We must be vigilant and – most important – we must understand what it is that we are protecting.

Protecting our reproductive freedoms begins with sharing our stories. Because abortion is not widely discussed in this country, at least in terms of the real people who actually access the service, it is not really understood. And I believe that it is not possible to appreciate and protect something without first understanding it. That is the purpose of this book: to bring compassion and understanding into a debate that is currently fractious and damaging.

Throughout this book I will refer to those who experience abortion sometimes as ‘women’ and sometimes as ‘pregnant people’. This is because, although the vast majority of the people who have abortions and whom I have encountered are cisgender women, not all of them are. It is important to acknowledge this, and I will talk more about the experience of trans patients in chapter six.

The almost total invisibility of stories about abortion, whether in books or in our own lives, means that women who find themselves in crisis, searching for comfort in the shared experience of others, have nothing to reach for. So they feel alone, at sea, like they have chosen to do an abnormal and therefore shameful thing.

Abortion care has always been about women reaching out, usually to other women, and asking for help. That help has shaped the course of entire lives and couldn’t be more vital. That is the tradition I feel I am continuing. I care deeply about my job, and I hope that by the end of this book you will understand why. I hope you will be as moved and galvanized by these patients’ stories as I have been. And armed with that new understanding, I hope we can better protect ourselves and each other.

Chapter 1

A Difficult Start

PEOPLE ARE USUALLY surprised when they learn that I am a midwife working in an abortion clinic. ‘Why have you left a job that’s so happy to do one that’s so depressing?’ patients ask. Family and friends often comment on what a wonderful job midwifery must be and gush over ‘bringing babies into the world’, as if that’s the only function of the role and it’s always happy. As a midwife, my driving force at work was always to support women. And with that sense of purpose, I have found vastly greater job satisfaction working in abortion care than I did working on a maternity ward.

Undeniably, there were lovely moments working in midwifery. I got to meet all kinds of people during what was mostly a magical time for them. While training, I did a lot of home visits and home births, as well as clinic sessions. Once I qualified, I enjoyed the autonomy of working with each family. The trust they put in me was humbling and gave me a real sense of responsibility and pride. I loved helping women bring their children into the world safely and felt extremely privileged to be there on the happiest day of their lives. I will always remember those families and those babies. I keep in touch with some of them to this day.

One of those people is Emily, whom I met in 2015 when she came into the ward for an induction. She and her wife were the first same-sex couple I’d met in my job, and I was excited because at the time I was planning my own wedding with my girlfriend. I helped them as they started the induction process, doing observations of Emily and the baby, and talking her through what the next few hours would hold. Throughout my thirteen-hour shift we also chatted about my own plans and hopes to have a baby in the next couple of years, and Emily told me about her experience of becoming pregnant through IVF. I wished her well as I ended my shift, and I returned the next day to find she had gone into labour overnight. I saw Emily’s surname on the postnatal ward list and, during my break, I popped up to congratulate them on the birth of their baby girl. As soon as I walked in I saw that Emily was very flustered. ‘The baby’s been asleep all night. She’s really red and jittery,’ she said. ‘The other midwives have said she looks normal and we should go home.’ I saw how worried she was and offered to test the baby’s blood sugar level – a heel prick test that takes just a few seconds. The result was the lowest level I had ever seen – equivalent to a diabetic person who was very sick. I tried to stay calm and told Emily: ‘It’s low so I’m just going to speak to the paediatrician.’ Thankfully the paediatrician was already doing their morning rounds of the ward and quickly transferred the newborn to the special care unit, where she stayed for a week. A few days later I bumped into Emily again, and she told me she’d really like to keep in touch on Facebook. I explained that while she was a patient that wasn’t allowed, but once she was discharged there was no issue. I’ve stayed in contact with only a handful of patients from my five years at the hospital and, at that moment, I had no idea how personally significant this encounter would turn out to be.

Initially, working on the maternity ward I got to spend a good amount of time with patients. I could sit with them, listen to their worries and give them the time they needed to feel cared for. If women wanted to spend an extra hour or two just feeding or relaxing and bonding with their baby, I was able to facilitate that. But very quickly my job became simply a mad rush. It was the start of the Conservative government’s policy of austerity, which involved deep cuts to public services, and the squeeze on resources was felt in healthcare settings almost immediately. The joy of a birth would be interrupted soon after by a knock on the door and the need to move the family out to make way for another. I came to dread that knocking, representing as it did the immense pressure that our team was under. There were more and more chaotic shifts, and the exhaustion started to kick in. As part of my contract, I had been required to opt out of the working time directive, which limited the number of hours you can legally work in a week. As a result of this, my colleagues and I were often working shifts of fourteen hours four times a week, without a break. I was bone-tired all of the time. Months before I quit, I realized that I couldn’t remember the last time I had had a good day at work – when I’d even had the space to sit with my team and have a cup of tea. Days off were not days in which to live the rest of my life, but just time to try to rest and recover before starting it all over again.

At the abortion clinic, patients have assumed I’ve been put there on a compulsory placement and not by choice. But they couldn’t be more wrong. Once I started working in abortion care, I found myself able to provide instant relief to women and offer them a way out of often dire circumstances. However, I certainly did not expect to end up working in an abortion clinic when I first began training in midwifery thirteen years ago.

*

My unusual journey through healthcare began when, as a teenager, doctors and nurses in the NHS saved my life and in doing so instilled in me the sense that caring for others is the only work worth doing. They rescued me from a desperate and dangerous place when, aged sixteen, I was diagnosed with anorexia. I was the classic case of an insecure teenager, a perfectionist always comparing myself to others and finding myself wanting. Somehow my self-worth had become inextricably linked with food. And anything I ate made me feel worse about myself. Over the course of a couple of years, as my self-esteem plummeted, I became more fixated on not eating, feeling that it was the only thing over which I could exercise control. Gradually, I stopped eating altogether. I clung to my new identity as a skinny and sick girl like a life raft.

My family noticed quickly that something was very wrong. For years I’d used food control at times of stress, but this was a significant escalation. It had started when my then boyfriend said he wanted to diet and I said I’d join him; he stopped after three days but I just became more and more obsessed. Around eight weeks after I had stopped eating completely, I weighed just 6 stone 4 ounces. My family took me to my GP and I was referred to an outpatient eating-disorders clinic, which was housed in a converted mansion. I dragged myself up two flights of stairs to meet the counsellor, Laura. I was automatically hostile and very sceptical of anyone trying to fatten me up. Despite the staff creating cosy consultation rooms with comfy chairs and colourful pillows, I found the community hospital incredibly daunting. Impervious to the strong central heating, I sat clutching a hot-water bottle – I was so emaciated that my body struggled to keep me warm. I was dreading the ‘help’ that I knew was about to be offered to me.

‘Your daughter has anorexia,’ Laura, friendly faced with soft brown hair, told my mum as she sat anxiously beside me. This scared me, because until this point I hadn’t quite accepted that they had the right diagnosis for me. I looked at this counsellor, wondering what she could possibly do for me when I barely had the energy to leave my bed. ‘Anorexia is like a toxic person taking over your body, Juno, and we need to stop her from silencing you,’ said Laura, beginning the work of separating me from this destructive disease.

Together we personified the illness and named her Ursula, and at home my parents stuck a picture of the mean witch from The Little Mermaid onto the fridge. Anorexia proved to be a wild rollercoaster. Victims of it become obsessed with perfection and by being seen as an ideal by those around them. I was no exception. The disease pulled me from wanting to be the perfect ‘thin’ person to wanting to be the perfect patient. I wanted to show them the most perfect recovery they had ever seen, with no hiccups! But some weeks when I put weight on, I then regretted it, blaming Laura and being rude to her. I witnessed other girls being even more aggressive towards their counsellors and throwing food at the wall during group therapy. One of the girls I met in group therapy, who didn’t scream and lash out but instead was eerily calm and committed to her anorexia, died not long after my time there.

It wasn’t until my brain started to function normally, with Ursula banished, that I began to see clearly the crucial effect that Laura had had. She was there at a time of absolute crisis for me, her patient. No matter how thankless the task, she would turn up to work each day with a plan that would ultimately save my life. I know now that anorexia has the highest mortality rate of any mental illness, and I never take for granted what she did for me.

Once I had recovered, I immediately knew I wanted to do something like Laura did, and after getting through the final two years of school with only partial attendance, I opted for a local midwifery course and started volunteering at mother and baby classes. As an eleven-year-old, I had written in my yearbook that when I grew up I wanted to be two things: a mum and a pop star. I know now that no amount of midwifery training fully prepares someone for parenthood (or, indeed, for pop stardom), but as an eighteen-year-old my aspiration for motherhood was part of what set me on my path to the labour ward. In the back of my mind, I thought it would be a shortcut to being the perfect mother when the time came.

I was thrilled by the first few months of training and felt I had truly found my calling. Midwife in Latin means ‘with woman’, which at the start of my career was certainly reflected in the focus on women-centred care. I was trained to nurture relationships with the women and their families, at a time when there was a strong emphasis on having the same midwife all the way through pregnancy and birth.

To qualify as a midwife, every trainee has to be responsible for at least forty live births. The first time I saw a birth, it was a long labour that ended with forceps, which entails the baby being pulled out with a sort of metal clamp around its head. I blacked out. It was an uncontrollable visceral response to what was an extremely graphic sight, however happy the outcome. At the next birth I cried tears of joy. It was a privilege to be there at such an important moment in this woman’s life, and I was tasked with making it as safe and happy as possible. I loved the work and couldn’t wait to get started.

But soon after I qualified, I found the reality very different to what I had been prepared for, and I soon understood that the care we were able to offer the patients on our busy London labour ward was fractured and inconsistent. I was shocked and disappointed. As a newly qualified midwife, over the first year I was given support by more experienced staff. But as soon as I tipped over into my second year, this was stripped away to make way for a new cohort who needed help.

A nearby hospital was closed down and merged with ours, leaving us inundated. Across the maternity ward, we had nineteen midwives and nurses working thirteen-hour shifts with a thirty-minute handover either side. Half of our team could be stuck on the labour ward, where patients must have one-to-one care. The rest were distributed across postnatal, antenatal, theatre and bereavement. Combined, we had more than sixty beds for patients and their babies. But it just wasn’t possible to use all of that space, because staffing levels meant we were unable to care for so many people at the same time.

Following a patient throughout her pregnancy became more and more unlikely, with women sometimes seeing a different midwife at every appointment. I still desperately wanted to build relationships and offer high-quality care to ‘my women’, as I thought of them. But it was becoming impossible. I had to learn to build a rapport quickly with my patients, knowing that often I would never see them again.

Even when a pregnancy is very much wanted, the whole experience can be overwhelming, and the patients I saw were vulnerable and sometimes afraid. A pregnant woman needed to lay her eyes on me and trust me, almost immediately, with her life. But I began to fear that I couldn’t give them what they needed. Eventually, the pressure on our meagre resources became too much. There was an extreme shortage of staff and labour rooms. Under such conditions, I was simply trying to keep mother and baby alive.

Some of the outcomes for the newborns on the ward during this period were terrible. They included babies starved of oxygen during birth, who had to have their bodies cooled in intensive care to keep them alive and minimize brain damage. Those newborns would be transferred to a different hospital because ours offered only the lowest level of special care. That meant we could handle babies who were in relatively poor condition in the short-term, but if they were severely premature or needed specialist treatment they had to be transferred. In reality, though, there wasn’t always time.

One young woman was brought in panting from an ambulance. We managed to get her over to a bed, only to discover that she was about to deliver at around twenty-six weeks pregnant. The patient spoke little English and we had no immediate access to her medical files, so I had no idea what to expect. The situation quickly descended into complete chaos and panic.

Paediatric consultants heard their alarms beep across the hospital as we paged them urgently; the ones that could rushed to the ward immediately. We grabbed plastic bags and doll-sized hats to warm the baby as soon as it was born, which happened after just a couple of pushes. The specialists dived in with their expertise, while calls were made to arrange a transfer for the newborn as soon as possible. I still don’t know whether the baby survived.

On another shift, a woman who had just given birth was transferred to the postnatal ward and ended up in a tiny side room due to lack of space, despite being very overweight and high risk. She collapsed, but it was not possible to easily move her due to her condition, her size and the fact that the bed was too wide for the room. Due to extreme staff shortages I, a newly qualified midwife, was the most senior clinician on hand and felt entirely unqualified to navigate this situation while keeping everyone safe. By the time we were able to move her, which was a messy and uncomfortable process involving a hoist, she was transferred by ambulance to a specialist hospital, where she almost died of meningitis. After that incident I became convinced that a woman was going to die on my shift and I couldn’t bear it.

The last year of my NHS career was spent on the postnatal ward, the most under-staffed and under-resourced area of maternity, where a lot of clinicians were reluctant to work. There, I was looking after increasingly higher risk patients who were being moved from the labour ward due to lack of space. They included women who needed blood transfusions and one-to-one care for a short time.

I had trained for three years and then worked for two years at the hospital as a qualified midwife. Even at that relatively early stage in my career, I was often left in charge of the whole ward, and sometimes I was the only member of staff, with a couple of agency midwives who had never worked in our hospital before. Patients and their partners became increasingly hostile and aggressive, as their expectations of care were consistently not being met. With so many women to care for simultaneously, we were always going to be late giving someone their medication or discharging them. It was a constant source of stress for everyone, with families feeling they were being put at risk. They probably weren’t wrong.

Towards the end of my time at the hospital, there was a sense of panic in every minute of a thirteen-hour shift. Overnight there were only three midwives for thirty women and their babies. We would forgo breaks and food rather than leave our colleagues overburdened or any of the patients at risk. I didn’t have time to sit down for a proper meal and relied on snacks and sugary drinks, and when I went home, my eating pattern was messed up by the odd working hours. I started to notice that I was losing weight, which was dangerous so soon after recovering from anorexia.

During this time it became clear to me that the notion of NHS staff as ‘superheroes’ was deeply unhelpful. Caregivers are mere mortals and can only work so hard before they break. I held out for as long as I could but, just two years after qualifying, I was twenty-five years old and completely burned out. Older staff who had been there for decades also expressed their desire to leave, but many had only a few more years before retirement so decided to stay. I couldn’t face a possible forty-year career in those conditions. I wouldn’t have made it through physically or mentally.

I had been battling with the idea of leaving for some months, waiting for things to get better out of loyalty to the NHS and not wanting to abandon my colleagues. But my resignation was somewhat abrupt. After another anxious drive to work, thinking about what the day might bring, I arrived to face a full ward with not one bed available. Minutes after the early morning handover, a call came from the labour ward pressing us to discharge some patients because they had three women who needed a bed. I hung up the phone and went straight to the computer to write my one-sentence letter of resignation. I am not by nature an impulsive person, but this was the final straw and the push I needed.

On handing in my resignation, when I mentioned the startling dropout rate, the maternity matron said: ‘This always happens, it’s a spring clean.’ She had been in the NHS for forty years and was one of my mentors, but she didn’t bat an eyelid as scores of midwives left, taking their years of training and experience with them. Fourteen other staff from the maternity ward in my hospital left the same month I did. I felt guilty leaving the hospital which had trained me, and I also felt a kind of grief; I had never imagined this was how it would end. I’d assumed I would have a fifty-year career in my local hospital, where any friend or relative that was sick would come for treatment. But by the time I resigned, I dreaded walking up the stairs to the ward. I would hold my breath as I turned the corner, the moment before my heart would sink as I saw the full list of patient names in the staffroom. I was angry because it turned out my best was just not good enough.

I looked around at alternative jobs, such as with domestic violence charities and organizations supporting refugees. I felt sad at the prospect of leaving the healthcare profession, but I didn’t know of any alternatives to midwifery roles.

When the managers of local abortion clinics realized what was happening, they saw an opportunity. They know that midwives usually want to stay in the field of caring for women. After spotting an advert for a role at one of these clinics, I wondered if this was the answer: a different way to support pregnant patients.

I was aware of the debate around abortion provision, but had no experience of it personally and had not given it a detailed amount of thought. It certainly hadn’t come up in my midwifery training. Though I had always considered myself pro-choice, I confess I vaguely thought of abortion as a service used mostly by people who had been reckless. At the clinic, I would quickly come to understand that, overwhelmingly, this is not the case. Many patients are careful, many are already mothers, and nearly all are people who have come to this agonizing decision for good reasons. I began to hear from so many women that they were anti-abortion until their situation changed, and I now believe almost anyone would undergo the procedure under certain circumstances. Indeed, in the years to come, girls and women would come to me at the abortion clinic and declare themselves firmly anti-choice, before explaining that their personal situation made it acceptable on this occasion.

Before I left the maternity ward, I had heard ominous things about the clinic from some of my hospital colleagues, whom I later understood held deep prejudices. They recounted tales of distressed women turning up on the labour ward when something had gone wrong with their procedure, frightened and in pain. There were whispered rumours that clinic staff ‘weren’t real doctors’ and ‘don’t even bother to scan their patients’.

I had grown up in a very liberal family, and though I believed in women’s reproductive rights, I didn’t imagine it was something that would affect me directly. Until I met my future wife, I had only been in relationships with men and had always been very careful with contraception. I had taken the morning-after pill once, when I was on antibiotics that could have interfered with the effectiveness of my contraceptive pill. I thought this vigilant risk-averse attitude would mean I would never need a termination. But I soon realized that even now, in a long-term same-sex relationship, the chance remains that I could find myself in a situation where I need an abortion, as the stories that follow will show.

While some of my colleagues were keen to criticize our local clinic, I’m embarrassed now to think that I really didn’t know much about abortion at this stage. No one close to me had yet told me about their terminations and so I thought abortions were just a few extreme cases.

But on the rare occasion a woman came into the hospital because of a poor outcome from an abortion, the staff’s attitude was always one of disgust. No one ever really challenged this negative perception, even though I’ve had discussions with friends working at the NHS since who are by no means anti-abortion. But I witnessed a real hierarchy whereby younger staff would not question a senior colleague’s opinion. I did not feel I had either the knowledge or the authority to challenge these attitudes at the time.

Officially, each clinic has a relationship with its nearest NHS hospital so that any patients in need of specialist care can be quickly transferred and we can directly liaise with the relevant team there. Hospital staff are also supposed to have a thorough understanding of the procedures that abortion clinics carry out and the medications used. But in practice this is not always the case and, unfortunately, midwives and doctors often go through their entire medical career without ever visiting an abortion clinic or learning thoroughly about the procedures performed there. Relationships between hospitals and clinics are therefore often fractured and not the positive, supportive connection that would enhance patient care.

During my midwifery training, I saw staff attaching stigma to abortion. Once, I was looking after a woman in labour who had a termination listed in her medical history. When a midwife was doing the handover to her colleague, she ran through the patient’s history out loud but only silently pointed to the line where the abortion was mentioned. This practice is also adopted for drug users, and I saw it used repeatedly as I learnt the ropes on the ward. It is an indication that you believe that particular detail is something the patient is likely to feel awkward about or ashamed of. Something not to be discussed.

But I did witness sympathy from staff for some patients undergoing terminations at the hospital, for example those that are terminating due to fetal abnormalities. The NHS is a lifeline for women who cannot be treated at a clinic, such as those needing an abortion after twenty-four weeks – the usual legal cutoff – or with special medical needs. At the clinic now, I refer patients for a hospital abortion every week. I remember one patient, a wheelchair user who came in with her partner. She had suffered multiple strokes, was severely anaemic and had asthma. In her early forties, she was very fearful of the health implications of a pregnancy. She was on a lot of medication and wasn’t well enough to take abortion pills at home. I took down her medical history, scanned her and got her an appointment at the local hospital. Staff there were able to accommodate all of her mobility challenges. Despite what I see as an insufficient understanding of abortion provision within the institution, I know that the NHS will always take and care for these patients when that care is needed.

From working on the maternity ward, I knew that many of my colleagues were under the false impression that abortion-clinic staff conduct risky procedures and didn’t understand that the handful of patients admitted to hospital after a procedure at a clinic represents an extremely small proportion of abortions. Across England and Wales in 2021, complications, including haemorrhage, sepsis and cervical tear, arose in 0.14 per cent of abortions. (The available information is limited in detail – the government is currently reviewing how it collects the data to give a clearer picture.)6 Women are always informed of the risks before any procedure and, unfortunately, out of hundreds of thousands of terminations in the UK annually, some patients will experience complications. No procedure in any healthcare setting is entirely risk-free.

As with other operations, a surgical abortion carries a small risk of an instrument piercing a muscle or organ. Another reason to transfer a patient to hospital would be a haemorrhage. Abortion clinics are prepared for this with blood supplies, but a haemorrhaging patient will nonetheless be transferred to hospital so that they can stay overnight to be monitored. When women were admitted to hospital due to complications from an abortion, I had often heard staff refer to their cases as ‘barbaric’, even though there can be the exact same outcome from a Caesarean. These are extremely rare events. They are just the only ones that hospital staff encounter.