11,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: John Wiley & Sons

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

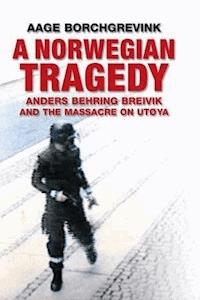

On 22 July 2011 a young man named Anders Behring Breivik carried out one of the most vicious terrorist acts in post-war Europe. In a carefully orchestrated sequence of actions he bombed government buildings in Oslo, resulting in eight deaths, then carried out a mass shooting at a camp of the Workers’ Youth League of the Labour Party on the island of Utøya, where he murdered sixty-nine people, mostly teenagers.

How could Anders Behring Breivik - a middle-class boy from the West End of Oslo - end up as one of the most violent terrorists in post-war Europe? Where did his hatred come from?

In A Norwegian Tragedy, Aage Borchgrevink attempts to provide an answer. Taking us with him to the multiethnic and class-divided city where Breivik grew up, he follows the perpetrator of the attacks into an unfamiliar online world of violent computer games and anti-Islamic hatred, and demonstrates the connection between Breivik’s childhood and the darkest pages of his 1500-page manifesto.

This is the definitive story of 22 July 2011: a Norwegian tragedy.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 625

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Ähnliche

Table of Contents

Title page

Copyright page

Preface

1: The Explosion

2: Bacardi Razz

Skaugum

The Consumer Zombie

‘I'm Going to Kill You!’

The Herostratic Tradition

The West End

3: A West End Family

‘The Fatherless Civilisation’

A Suspicious Smile

The Dark Sources

The Cats of Ayia Napa

4: Morning on Utøya

Utopia on the Tyrifjord

Utøya at Its Best

‘We Must Be Vigilant Now’

Stop Them with Spirit

5: Morg the Graffiti Bomber

King of the Number 32 Bus

A School with Class

The Bomber from Ris

Growing Pains in the Nineties

The Aesthetic of Destruction

The Tåsen Gang

The Tadpole Mafia

The End of Morg

6: The ‘Mother of the Nation’ Returns to Utøya

Wearing Bano Rashid's Wellies

11 September 2001

Ideas That Kill

Occidentalism, Norwegian Style

Mecca

7: Andrew Berwick and Avatar Syndrome

The Entrepreneur

Andersnordic, Conservatism and Conservative

Avatar Syndrome

The Counter-Jihadist Avatar

The Online Prophets of Doom

Critics of Islam and Their Norwegian Godfather

Home to Mother

‘It's Going to Be the Event of the Year’

8: The Safest Place in Norway

Shock

Planet Youngstorget

North Along the E18

The Information Meeting

Camping Life

Faces

9: The Book Launch

A Declaration of Independence

Conspiracy and Castration

The Suicide Note

Hatred of Women

10: Survivors

The Ferry Landing

Ida Spjelkavik

Arshad Mubarak Ali

Stine Renate Håheim

Anzor Djoukaev

11: Rescuers

Heroism on the Tyrifjord

Allan Søndergaard Jensen

Anne-Berit Stavenes

Erik Øvergaard

12: What Is Happening in Norway?

Shooting in Progress

Terror in Buskerud?

What the Camera Saw

When Fear Takes Over

The Captain and His Ship

13: Anders Behring Breivik's Seventy-Five Minutes on Utøya

The Killings at the Main Building, 17:17–17:22

The Killings in the Café Building and by the Love Path, 17:22–17:44

From the Schoolhouse to Stoltenberget, 17:44–18:10

From the Pump House to the Arrest, 18:10–18:34

The Perfect Executioner

Evening on Utøya

14: Hatred

The Utøya Generation

The Heart of Darkness

The Lost Child

Acknowledgements

Index

First published in Norwegian as En norsk tragedie © Gyldendal Norsk Forlag AS, 2012. Norwegian edition published by Gyldendal Norsk Forlag AS, Oslo. Published by agreement with Hagen Agency, Oslo, and Gyldendal Norsk Forlag AS, Oslo.

This English edition © Polity Press, 2013

English Translation © 2013 Guy Puzey

The right of Guy Puzey to be identified as Translator of this Work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This translation has been published with the financial support of NORLA.

Polity Press

65 Bridge Street

Cambridge CB2 1UR, UK

Polity Press

350 Main Street

Malden, MA 02148, USA

All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purpose of criticism and review, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher.

ISBN-13: 978-0-7456-7220-5

ISBN-13: 978-0-7456-8002-6 (epub)

ISBN-13: 978-0-7456-8001-9 (mobi)

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

The publisher has used its best endeavours to ensure that the URLs for external websites referred to in this book are correct and active at the time of going to press. However, the publisher has no responsibility for the websites and can make no guarantee that a site will remain live or that the content is or will remain appropriate.

Every effort has been made to trace all copyright holders, but if any have been inadvertently overlooked the publisher will be pleased to include any necessary credits in any subsequent reprint or edition.

For further information on Polity, visit our website: www.politybooks.com

Preface

A year ago today, on 24 August 2012, Anders Behring Breivik was found guilty of killing seventy-seven people, violating sections 147 and 148 of the Norwegian Penal Code, which cover acts of terrorism, and section 233, premeditated murder where particularly aggravating circumstances prevail. The prosecuting authority's plea that he be transferred to mental health care was not upheld. The court found Breivik criminally sane and sentenced him to preventive detention for twenty-one years.

Thus a chapter came to an end. The events of 22 July 2011 had not only been scrutinized in detail by possibly the most comprehensive court case in Norwegian history, but had also been thoroughly investigated by the 22 July Commission and almost endlessly discussed in the media. Nevertheless, there are still aspects of the case that have not been reported widely. The extent of the detailed discussion has perhaps also meant that the bigger picture has become fragmented. How can we understand 22 July 2011?

A single book cannot describe such a great tragedy, but a book can still go into further depth than an article or a television programme and attempt to create a narrative or analysis of the events. Ideally, then, a book may contribute to deeper understanding.

My work on this book took other routes than I had initially envisaged. I eventually encountered the dilemma of how much I should tell and where to draw the line. I made a different choice from most Norwegian journalists because I decided that some of the lesser-known elements shed light on the explosive hatred that had such deadly consequences. They have explanatory power.

This was not a simple assessment; rights came up against other rights. Those affected have the right to know as much as possible about the background to the catastrophe. Breivik and his family have the right to their privacy. With a case of such enormous dimensions, however, I concluded that openness weighs heavily as a consideration. This is why I chose to tell more about Breivik's background and family than was publicly known at the time, because the picture I would have painted otherwise would have been incomplete at best, if not false.

That decision left its mark on this book. I have written about the community that was attacked, AUF [the Workers' Youth League], and, in a broader sense, Norway. I have written about extremist reactions to the emerging new Europe, with a focus on Breivik's so-called manifesto. I have learnt a lot in the process. The events of 22 July showed that Norwegian society is strong, but also that some people are left out of it. The reasons for this are not always clear, including in this case.

The process of understanding what led to Breivik becoming such a radical outsider is important. Without knowledge of where the holes in the net of our society are to be found, it is difficult to mend them. On its publication in Norway in the autumn of 2012, this book caused a debate about writers' ethics and the roots of radicalization.Why do children from peaceful and prosperous societies end up as terrorists? While Breivik serves his possibly lifelong sentence, the discussion about the attacks on 22 July 2011 and the phenomenon of European terrorism continues. I believe that is a good thing, and this book is a contribution to that discussion.

Aage Borchgrevink

Oslo, 24 August 2013

The Tyrifjord and surrounding area, 22 July 2011 Redrawn from ‘Rapport fra 22. juli-kommisjonen’ [22 July Commission Report], Report for the Prime Minister, NOU 2012: 14, fig. 7.3, p. 118.

Utøya Redrawn from ‘Rapport fra 22. juli-kommisjonen’ [22 July Commission Report], Report for the Prime Minister, NOU 2012: 14, fig. 7.5, p. 120.

1

The Explosion

The bomb exploded at 15:25:22. The blast reverberated through the city. The van disintegrated. A motorcyclist and a chance passer-by vanished in the white flash of the explosion. A fierce fireball blinded the nearest surveillance cameras and was followed by a cloud of smoke and dust. Pieces of the van flew like projectiles in every direction, axles and engine parts spinning through the air.

At the scene, cars were flung around, and the lamp posts bent like blades of grass. The buildings on both sides of Grubbegata bore the brunt of the shockwave, completely destroying their lowest floors. The pressure wave pulverized the windows in the floors higher up, passed right through the building and smashed glass in other buildings around the square in front of the high-rise H Block. Ceilings collapsed above the offices in the H Block and in the Ministry of Petroleum and Energy. Splinters of glass and wood whistled through the corridors and offices, drilling their way deep into wall panels and cupboards.

The blast sparked fires on both sides of the street and gouged holes in the asphalt. The bomb crater gaped open right through two levels of tunnels running under the street. These corridors were used to transport documents between the ministries. The explosion cut deeply, uncovering hidden passageways and exposing the very nerves of administration in Norway. There was a smell of sulphur, like rotten eggs.

Eight minutes earlier, at 15:17, the large, white Volkswagen Crafter van had turned in off the street called Grensen. It drove calmly up Grubbegata towards the government district and stopped on the right-hand side in front of a metal fence covered with a white canvas to hide the construction works outside R4, the building that housed the Ministry of Trade and Industry as well as the Ministry of Petroleum and Energy. The driver put on the hazard lights, as illegally parked vans often do, and made his final choice.

A couple of minutes later, the van rolled forwards again. It turned off to the left by the H Block, stopping outside the main entrance to the Office of the Prime Minister. A man in a dark uniform got out of the vehicle and walked on up Grubbegata. A security camera captured him on his way up the pavement: a man with a black helmet, a lowered visor and a pistol in his right hand, turning round and staring back at the van he had left behind. The time was approaching half past three in the afternoon on 22 July 2011.

It was a sleepy Friday in the summer shutdown.

At Tvedestrand, further south, a man stood on the jetty by his holiday cabin, studying the cloud banks hanging above the grey sea. It was the summer holidays, after all, even for the foreign minister. He decided to take his sons out trolling for mackerel, and went to change the hooks on his fishing line.

A young, dark-haired woman sat nodding off in a car heading in to Oslo. She was dressed up in red boots and red earrings and was tired after a night out with her friends.

The rain lashed down over eastern Norway – again. The summer of 2011 would go down in the history books as one of the greyest and muggiest in living memory. People in their holiday cabins stayed indoors; no point in going out into the mist. The grass was wet, and if you wore trainers your feet would just get soggy.

A woman lit a cigarette and took a break from preparing dinner in the kitchen. She had moved to a small coastal town by the Oslofjord after retiring from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, but she still kept a small bridgehead in the capital: a studio flat in the West End. That evening, Tove was going to have some friends round.

A student from Stavanger and his friend, a girl from Oslo wearing a black turban, spoke quietly in his small room in Kafébygget [the Café Building]. Outside the window, the damp foliage glistened, blocking the view of the grey lake Tyrifjord. They were taking a short break together before the afternoon's programme.

At 15:21, the administrative secretary at the Electricians' and IT Workers' Union logged off the network and got up from her desk. Holidays at last. The union had its offices on the seventh floor of Folkets Hus [the People's House], the Norwegian Confederation of Trade Unions' building, which dominated one side of the square at Youngstorget. To the left of Folkets Hus towered Folketeaterbygningen [the People's Theatre building], where the Workers' Youth League, among others, had their offices. The administrative secretary was a sprightly woman in her mid-fifties, a former Norwegian football champion. She usually cycled home, but that day she had taken her bike to be repaired. She was wearing light-coloured jeans, black trainers and a brown jumper. It had cleared up when she went out of the building. Since she was going to the metro station, she could walk either down towards Jernbanetorget or up past the government district and the entrance into Stortinget metro station. It was not far to go either way, but the secretary turned right and walked up the incline. She strolled along Møllergata and turned right up the alley leading to Einar Gerhardsens Plass.

In the meantime, the man in the helmet had crossed Grubbegata, walked down to Hammersborg Torg and got into a silver-grey Fiat Doblò. A man saw what looked like an armed policeman reversing the van out and driving down Møllergata in the direction of Hausmanns Gate. The strange thing was that the policeman was driving the wrong way down a one-way street. Was he completely disorientated? Why did the policeman choose to go that way? The man at Hammersborg Torg took out his mobile and made a note of the small van's number: V-H-2-4-6-0-5. Green plates.

In the government district at Grubbegata, there were people at work all day long, all year round. The buildings never slept, but on Fridays during the summer holidays most people left the office early. Normally, more than 1,500 people worked in the government district, but at twenty-five past three on this particular day there were only about 250 people in the buildings and 75 out on the street nearby.

At 15:24, the security cameras in Einar Gerhardsens Plass picked up a man in a white T-shirt walking towards the main entrance to the H Block. The man, in his early thirties, was possibly one of the people who usually took the short cut through the lobby, past the guards behind the desk on the left, on the way to the exit onto Akersgata. The lobby underneath the Office of the Prime Minister was open to the public. Less than a minute later, a motorbike stopped next to the Volkswagen Crafter. In the back of the large van was a homemade bomb weighing approximately 950 kg, consisting of fertilizer, diesel and aluminium. It exploded.

On the streets of the city centre, the pressure wave mowed down people on the pavements. A man was thrown onto the asphalt, as if by an invisible hand. He immediately got up again and tried to find his bearings. Some pedestrians lay in foetal positions, lifeless, while others immediately ran away. In a busy street, first one person, then three, and eventually the whole crowd ran in panic, as fast as they could, away from the site of the explosion.

A dying woman in light blue jeans was left lying by the fountain in Einar Gerhardsens Plass.

A cloudburst of glass rained down over the city. All around Youngstorget, shards of glass from the shattered windows smashed down onto the paving stones. Out in the square, a woman touched her head and stared at her hand, which was red with blood.

The centre of Oslo is compact. It is only a couple of hundred metres from the government district to the Storting, the main party offices and the biggest media centres. If a radius is drawn out another few hundred metres from the government district, then Norges Bank, the Royal Palace and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs also fall in the circle. It was possible to drive up to any of these buildings. When the raining glass had subsided, dozens of people lay, sat and walked around the centre of Oslo with blood streaming from cuts to their heads, arms and shoulders.

Within a few minutes, the pictures of R4 in flames, Grubbegata strewn with wreckage and the mangled H Block were being seen around the world. The pictures spoke for themselves. Devastated buildings, dust, smoke, people in shock and bleeding. Similar pictures had been broadcast many times over the past twenty years: Oklahoma City in 1995, Nairobi and Dar es Salaam in 1998, Moscow, Buynaksk and Volgodonsk in 1999, New York in 2001, Bali in 2002, Beslan in 2004, Mumbai in 2008 and, time after time, towns in Israel, Iraq, Afghanistan and Pakistan.

The damage being seen by television viewers around the world seemed to have originated outside the building. ‘A car bomb?’ wondered a man walking up Grubbegata as he filmed the inferno.

Over the course of the counterfactual hours before it became clear who was behind the bomb, many dark-skinned Norwegians in Oslo instinctively kept their heads down. The signature of al-Qaeda seemed to be written all over the Norwegian government district in fire, glass and blood. The explosion in Oslo struck like a bolt of lightning at the social and political landscape in Norway, splitting open divides like chasms. Could immigrants be behind it?

A foreigner watching the television pictures from the centre of Oslo while he commented on an English-language forum wrote that he ‘did not know Norwegians looked like Arabs’. A well-known Norwegian blogger immediately answered: ‘In Oslo they do. Arabs, Kurds, Pakistanis, Somalis, you name it. Anything and everything is fine as long as they rape the natives and destroy the country, which they do.’1 Who was the blogger representing when he wrote that ‘the left-wing government of Jens Stoltenberg that was just bombed is the most dhimmi [and] appeasing of all Western governments’? The term dhimmi describes non-Muslims who live under sharia, and in this case probably meant something along the lines of repressed and cowardly.

The notion of Norway as characterized by a sense of community and solidarity, as a harmonious island in a troubled world, faded. Had Norway suddenly ended up in some kind of revolutionary situation without most people noticing? The stench of the bomb was pungent. A layer of smoke descended on Oslo, obscuring the question of what was rotten in Norwegian society.

Shortly before four o'clock, I stood in front of the physics building on the University of Oslo campus and stared over the roofs towards the centre of the city. The cloud of smoke rose up from the government district and hung over the city centre for a while before slowly dissolving and disappearing. The surreal sight reminded me of burning villages in the Balkans and bombed towns in the Caucasus. Complicated local situations often lay hidden behind the suicide attacks and massacres I had investigated there. But here, in Oslo? It was hard to fathom.

I thought about my parents’ accounts of 9 April 1940, when German aircraft swarmed over the city and Vidkun Quisling staged a coup d'état live on Norsk rikskringkasting [Norwegian Broadcasting Corporation; NRK] radio. Most of all I thought about the fallen towers in New York in 2001, and about the ideology that unites terrorists of many stripes in a common hatred towards Western cities and all that they stand for. The explosion was of such a magnitude that it appeared to be a declaration of war, an attack of geopolitical dimensions.

Yet this was only the beginning of the tragedy. Not only would the follow-up be more horrific than anybody could imagine, but the course of events would turn out quite differently to any preconceived notions. The man in the helmet was not dark-skinned, but white. Hmm, I thought, when I heard that: Chechen? Bosnian? Albanian? This must have originated in a distant warzone. No, it was not that straightforward. The man was neither Muslim nor a foreigner but one of my neighbours from the West End of Oslo.

In order to get closer to the origins of this atrocity, I would have to go not further away, but deeper. As I explored the dark online worlds of the past decade, fantasy culture and Oslo gangs of the nineties, I found that I kept on crossing my own tracks. What appeared to be political extremism, and in a way was, would turn out to have a complicated local dimension at its core here too. Some people had seen a monster taking shape, but their ignored warnings lay buried beneath layers of time, and witnesses were silent.

As I walked back through Marienlystparken [Marienlyst Park] with my mobile phone in my hand, I tried to find out how my friends and colleagues were doing in the city centre. The ambulances screeched down Kirkeveien from Ullevål Hospital. Sometimes, the solution is closer than you think, and hatred is written on the wall where nobody notices it. By chance, a friend of mine had seen a glimpse of it at a bar in the autumn of 2010.

Notes

All translated quotations from non-English-language texts are the translator's own, unless indicated otherwise. Quotations from Breivik's compendium are reproduced as in the original English text, although some minor changes have been made to punctuation and capitalization.

1 These comments were made on a blog post by Edward S. May (Baron Bodissey), ‘Terror Attack in Central Oslo’, Gates of Vienna, 22 July 2011, http://gatesofvienna.blogspot.co.uk/2011/07/terror-attack-in-central-oslo.html, cited in Øyvind Strømmen, Det mørke nettet [The Dark Net] (Oslo: Cappelen Damm, 2011), p. 17.

2

Bacardi Razz

Skaugum

In mid-July 2011, the regular customer turned up for a last drink at Skaugum, an open-air bar at the back of the Palace Grill near Solli Plass in the West End of Oslo. It was the middle of the week, but there was little difference between weekdays and the weekend when everyone was on holiday. When the weather dried up, people flocked to bars and cafés like swarms of ants. The man pushed his way forward through striped shirts, hoodies and lace tops to order a Bacardi Razz, a sugary raspberry-flavoured rum that in Oslo's West End bars is often mixed with Sprite, decorated with a slice of lime and called a Butterfly.

The customer was quiet and polite as usual.1 He was a typical West End boy, or man, of the sort that were two a penny at Skaugum, and he did not stand out apart from being less drunk and loud-mouthed than most of the others. He was medium height, blond and with an average build, in good shape. The bartender remembered the customer well from his days at Oslo Commerce School, one of the neighbouring buildings, in the late nineties. Over the years, as his hair slowly became thinner and his jaws rounder, he had continued to come back to the Palace Grill.

Most of the other boys from the nineties had got degrees and careers, grown up and settled down, but this regular customer had not followed the usual path from the Commerce School to a secure job in trade or industry. He did not have to pick anyone up from nursery at four o'clock and did not get up at seven to go to work. Some take longer to find themselves, and an unmistakeable aura of interrupted studies and failed business ventures surrounded the customer at the bar. ‘Get rich or die tryin’, he had said to his acquaintances in the Progress Party youth wing early in the noughties, quoting the rapper 50 Cent.2 But he was not much richer on this mild summer evening ten years later than he was back then.

Some of his businesses had made something, while others had gone quite badly. He had earned good money selling cheap phone call packages and fake diplomas, but his friends were still laughing about some of his ideas. For several months he had worked on his ‘unemployed academic’ project. He had developed a prototype of a pedal-driven billboard by putting together a bike and a newspaper cart. His idea was to take on an unemployed academic (of whom there were plenty, he thought) to cycle the vehicle with the billboard round Oslo: mobile advertising or, alternatively, ads-on-wheels.

It did not go well. The wind blew the cart over on the very first day, sending the billboard flying off to hit a woman. The ‘unemployed academic’ project was abandoned after its maiden voyage. Maybe his ideas were a little too big. The plan was not only about earning money but perhaps more about humiliating academics. Even though his friends thought he was enterprising, he was often strange and obstinate.3 An odd eccentric who wore sunglasses around town, even though it looked peculiar in the evening, and who was perpetually vain, wearing a Canada Goose-branded down jacket in the winter or with his shirt collar folded up under his Lacoste jumpers. A metrosexual, as he said himself. Before he went out, he put on make-up. He was considering hair transplants and dental bleaching. He had a nose job done when he was twenty.

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!