Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Birlinn

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

Longlisted for the Highland Book Prize 2019 When Les and Chris Humphreys moved to Ardnamurchan 15 years ago, little did they realise they would be sharing their home with some of Britain's most elusive and misunderstood mustelids. Amongst all the animals and birds that visit their garden, they have formed a special bond with numerous pine martens, and have studied them and a cast of other creatures at close range through direct observation and via sensor-operated cameras. Naturalist and photographer Polly Pullar has known the Humphreys and their pine martens for many years. In this book she tells the remarkable story of the couple and their animal friends, interpolating it with natural history, anecdote and her own experiences of the wildlife of the area. The result is a fascinating glimpse into the life of a much misunderstood animal and a passionate portrait of one of Scotland's richest habitats – the oakwoods of Scotland's Atlantic seaboard.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 332

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

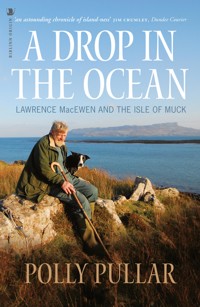

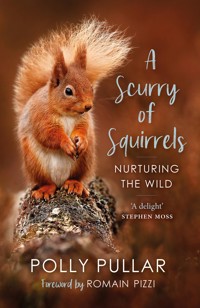

Polly Pullar is a field naturalist, writer and photographer who grew up in Ardnamurchan. She is also a wildlife rehabilitator. She contributes to a wide selection of magazines, including the Scottish Field, People’s Friend, the Scots Magazine and BBC Wildlife. She is the author of a number of books including, A Drop in the Ocean: Lawrence MacEwen and the Isle of Muck, The Red Squirrel – A Future in the Forest and co-author of Fauna Scotica: Animals and People in Scotland.

Sir John Lister-Kaye is an acclaimed naturalist, writer and lecturer who is also Director of the Aigas Field Centre in the Scottish Highlands. His books include Nature’s Child: Encounters with Wonders of the Natural World, At the Water’s Edge: A Walk in the Wild and Gods of the Morning: A Bird’s Eye View of the Highland Year, which was awarded the inaugural Writer’s Prize by the Richard Jefferies Society in 2016.

First published in 2018 by

Birlinn Limited

West Newington House

10 Newington Road

Edinburgh

EH9 1QS

Copyright © Polly Pullar 2018

Foreword copyright © John Lister-Kaye 2018

Line illustrations copyright © Sharon Tingey 2018

ISBN 978 178885 070 4

The right of Polly Pullar to be identified as Author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright,

Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form or by any means without permission from the publisher.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Designed and typeset by Initial Typesetting Services, Edinburgh

Printed and bound by Gutenberg Press, Malta

For Freddy and Iomhair,and Les and Chris’s family – Tim, Kathryn, Lizzie,Chas and Struan

CONTENTS

Acknowledgements

Foreword: The pine marten – a personal view, by John Lister-Kaye

Introduction: A brief glimpse

1. Oaks of the western seaboard

2. Early encounters

3. Eggs for tea

4. A question of feeding

5. The loch

6. A richness of martens

7. Sea eagles and spectres from the north

8. Bugged

9. Antics

10. More about martens

11. Of mice, shrews and weasels

12. Snipe by moonlight

13. More visitors

14. Of frogs, otters and shearwaters

15. Baffling badgers

16. Life and death

17. Small miracles

18. Walking the plank

19. Cuckoos and golden eagles

20. On the track of the marten

21. The storm

Family tree

Pine marten duration of stay

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I would like to thank the many people who have helped me, both directly and indirectly, to write this book. Firstly, Sue and Dochie Cameron. Not only did Sue introduce me to Les and Chris Humphreys, but over many years she and Dochie have provided me (and the collies) with a wonderful haven where I can write in peace. I would also like to thank Dochie for lugging in a table on each of my visits to Ockle for use as an all-important desk, and both him and his brother Dougie for dealing with water, electrics and various other domestic snags caused by the weather, or the mice!

Thanks also to my son Freddy and my partner Iomhair for unstinting support and understanding. To John and Lucy Lister-Kaye, whose work at the world-renowned Aigas Field Centre provides constant inspiration, and in particular to John for the lovely piece he has written to open my story. To Sharon Tingey for her sensitive illustrations and patience with an ever-changing remit. To wildlife photographer Neil McIntyre for the book’s front cover photograph. To Rob and Becky Coope for their input and valuable friendship. To Jim Crumley, wildlife kindred spirit with whom I often discuss our shared concerns for the future of the natural world. To Colin Seddon and Romain Pizzi, whose tireless wildlife work is inspirational and makes so much difference. To magazine editors Angela Gilchrist, Robert Wight and Richard Bath for giving me endless scope to write about what I love best. To Evelyn Veitch, who cares so beautifully for our burgeoning menagerie during my absences from home. To Dr Debbie Shann, who will understand why. Special thanks to Kevin and Jayne Ramage, and Sally and Dorothy of the Watermill Bookshop, Aberfeldy, for continual support and enthusiasm with literary ventures various. Special thanks also to Andrew Simmons of Birlinn, who is always such a pleasure to work with, and copy-editor Helen Bleck, who has also been a joy as well as an invaluable help. And of course to my publisher, Hugh Andrew, and the rest of the team at Birlinn.

None of this would have come about without the extraordinary dedicated input and patience of Les and Chris Humphreys themselves, who have put up with endless queries and cajoling from me, and sifted through reams of video footage and diaries to confirm information. They have been delightful to work with, and I want to thank them for all they have done and for trusting me with their extraordinary story.

And, finally, Les and Chris would like to thank Sue and Dochie, and Liz and Sandy for all their help and support over the years.

Polly PullarMay 2018

FOREWORD

The pine marten – a personal view

There is blood on the snow

and a trickle of rowan berry juice

on his bib where the pine marten

stands for a moment like a man.

from ‘The Pine Marten’,by David Wheatley

Just a memory now, fading but still there. That first glimpse, that splash down into realisation that such a creature still existed. I’d like to be able to say that it was just so, in such-and-such a place, precise and named. A moment so electric and unforgettable that even after all these years I could still tell you when – the year, the month, the day. I’d like to boast that it spun me into instant awareness or understanding, or love or obsession, or something – that it’s permanently branded. But no, I’d be lying. It wasn’t like that at all. It was a moment fogged with doubt, even disbelief – could it be . . . ? Was that a . . . ? Have I just seen . . . or am I fooling myself? Perhaps it was a just a cat.

It was so rare back then, rarer than a wildcat and as rare a sighting as an osprey – that now-much-cherished, cream and mocha fish-eagle gamekeepers had blasted to the brink of legend because ospreys had the temerity to eat salmon and trout. That was the way of things in those days, a relentless, focused persecution of any raptor and any carnivore, a tyranny almost never challenged. And no one seemed to care. The marten had gone the same way. After centuries of being hunted by Highlanders for their glossy, mink-like fur, when Victorian gentry refashioned the Scottish Highlands into a preserve for red deer, grouse and salmon, and gamekeepers were appointed as armed, over-zealous warlords to patrol and terrorise their vast upland estates, all predators were outlawed. Martens were poisoned, shot and taken with that most vicious of cruel weaponry, the tooth-jawed gin trap. A singular and determined extirpation was the only goal. That is why they became so rare. They were clinging on – just – by a claw and a whisker, and then only in the remotest mountain wilds.

So not so surprising that I couldn’t believe my eyes, couldn’t be sure that I had seen right. But it was. A furry dash across a twilit, single-track road somewhere up a glen – and I can’t even remember exactly which glen. And then nothing. It had vanished into an ocean of impenetrable broom and gorse. I stopped the car, reversed back, waited, got out, ran forward, ran back, willed it to show again. Nothing. It had gone. But I knew in the marrow of my bones that I had glimpsed one of Britain’s rarest mammals – Martes martes, a pine marten, the most agile and beautiful of the British mustelids, the weasel family. That second-long sighting had hoiked it back from literary obscurity. No longer was it just a name on a page or a blurry photograph in a book, as remote and impersonal as an ad on a hoarding. I had seen it in the flesh for myself. It had lived and moved and, for the blink of an eye, it had shared with me its agile, lissom, Bournville being.

That was then: some time back in the 1960s, when much of the Highlands was still a frontier of windswept, echoing emptiness. In the nineteenth century many of its people had fled to the New World or to southern cities for jobs, peeling away from the glens like blown leaves, a diaspora continuing well into the twentieth century, horribly compounded by two world wars. Many thousands of Highland men and boys never returned, leaving their pocket-handkerchief fields and tumbledown cottages to the sheep and the crows. As always happens when you give nature half a chance, wildness had come clambering back, filling the vacant niches, shouldering in with what biologists call ‘succession’, a land- and a hill-scape silently returning to the solace of its own flowers and trees and shrubby scrubland, its own bugs and bees and secret habitats. For centuries razed by half-starving Highlanders and their livestock, the hills and glens were once again going wild.

Then in the 1970s commercial forestry motored in, ringfencing whole valleys and deep ploughing the moors for Sitka and Norway spruce plantations. It became a craze – a plague even – transmogrifying entire landscapes into the coniferous uniformity of cornfields as far as the eye could see. Yet, in the way that an ill wind blows nobody any good, those deep, unsightly furrows broke through the blanket peat and iron pans to provide a turnover of nutrients that allowed weeds and other nutritious plants to burgeon. That new growth fostered a brief population explosion of voles, essential food for hen harriers, barn owls, kestrels, wildcats, foxes and yes, pine martens, all of which enjoyed a short-lived bonanza. As the young conifers established to the thicket stage, no longer able to hunt, the birds drifted away, leaving only an ever-darkening sanctuary for the previously persecuted wildcats and martens.

A decade slid past and those dark Sitka forests yielded up an expanding population of pine martens, unseen, uncounted and unstoppable. That is what happens when you give nature half a chance. The species was clawing its way back from the brink, accidentally rescued by one of the most extensive land-use transformations to storm across the uplands in centuries. But as the conifer canopies closed off the sunlight and the field layer of plants died away, so did the voles. By the 1980s martens were still able to exploit dark forests for safety, but were forced out into the wider man-occupied landscape for their food.

It was during those years that we established Aigas Field Centre in Strathglass. We didn’t know it at the time, but that happy resurgence of pine martens was occurring right on our doorstep, in our woods and other people’s woods up and down the glen. Eventually, by 1982, a bitch marten had whelped in the roof of an abandoned shed beside the Aigas Lodge cottage. Four enchanting kits entertained us that summer, popping up on bird feeders and delighting our guests. It would prove to be the beginning of a long and happy symbiosis, the martens enjoying our protection and our visitor numbers increasing year on year, as we became known as one of the few places in Scotland where martens could reliably be seen. We built a hide. To this day at Aigas every summer many hundreds of people enjoy close encounters with this special mammal.

To suggest we’ve become blasé is wrong. We never tire of seeing pine martens. I have long since lost count of the individual animals I have known over the years, literally dozens, but it never palls. We see them at night from the floodlit hides, and we meet them face-to-face about the estate all the time. We never know where next. It could be in a stable or a barn, skipping along a balcony rail outside the guest accommodation, checking out the hen run in the early morning, or nipping cross a roof in broad daylight.

* * *

It is the 15th of September and the cycle of our field centre year is almost complete. Today dawned calm, chill but not cold, and as fresh on the cheeks as a splash of cologne. These fleeting moments of the autumn are among those I cherish most. Before the equinoctial gales sweep in from the west and night temperatures crash to ground frosts that sugar the morning lawns, there are great riches to celebrate. The mysterious world of fungus shows its hand. Fruiting bodies emerge from nowhere, bursting out of tree trunks or levering the earth aside mole-like to surface and spread their delicate gills and pores. Eugenia, the centre’s creatively inspired cook, heads off into the birch woods with a trug over her arm and a broad cep-and-chanterelle grin herding her cheeks up under twinkling eyes.

She is also to be seen emerging from a thicket or from under a hedge, hair in knots and tangles as wild as the undergrowth where she has been harvesting nature’s free fruits. As the first streaks of colour creep into the foliage, as the bracken turns to rust and the deer-grass, Trichophorum cespitosum, the common, wiry grass of the uplands, lends a ginger wash to our hill ground, so the branches of every rowan tree are drooped with tight clusters of scarlet berries as blazing as a harlot’s lipstick. Eugenia will collect baskets of them to boil down and render into rowan jelly, a mildly tart accompaniment for venison, other game such as grouse, woodcock and duck and, best of all, with good oldfashioned mutton. She will produce dozens of jars of the bright orange-pink jelly, a supply to keep us going all year. In a week or two these trees will be stripped bare by migrating thrushes, fieldfares and redwings from Scandinavia, undulating across our hills and glens in their tens of thousands, but for now they attract another unusual marauder, as well as Eugenia.

No one expects a carnivore to have a passion for fruit, especially not a fruit that appears to be so unpalatable. To the human tongue rowan berries are almost impossible to eat raw. The soft red flesh produces a bitterness as sharp and dry as a crab apple, with so sour and grimacing an after-taste it leaves your soft palate cringing even when you have quickly spat them out. No one in their right minds would eat rowan berries off the tree. For Eugenia’s jelly they need to be boiled down, the seeds strained out and then oodles of sugar and the same quantity of cooking apples added before the bittersweet juices coagulate into a surprisingly delicate and piquant flavour.

No such refinement for the pine marten. He takes his berries raw off the tree – and he gorges on them every September. We don’t really know why this is, but it seems likely that they are a rich source of vitamin C, which may be lacking in their diet if other mammal prey species, such as field voles, are in short supply. Pine martens are omnivorous despite their pointedly carnivorous dentition. It is well known that peanuts and strawberry jam will attract them to bird tables, and they consume large quantities of blueberries and blackberries as well as other fruits.

On our bird tables I have tempted them with many delights: rhubarb crumble, apple pie, fruit cake, roast potatoes, baked beans and much more. They take the lot. Once in a week of vicious winter frost I took a hunk of stale fruitcake out for the starving blackbirds to pick at. No sooner had I turned away than a marten popped out from under a bush, leapt up onto the table, grabbed the entire hunk and made off with it back into the undergrowth, all while I was still standing there.

A few days ago I took off with Alicia, our Staff Naturalist, to explore some rowan trees up in the woods to see to what extent martens had raided them. We examined about twenty trees, all laden with dense clusters of fruit. Seventeen had been attacked. The problem for the martens is that although they are excellent climbers, the fruit forms on the outer extremities of the slender branches, too far out and too slender to carry the weight of the marten. So it has to climb up, get as close as it can, bite the twig off so that it falls to the ground, and then nip down and feast on the spoils. Most of the trees we examined had a ring of scattered berries and stripped clusters around them. I had never witnessed this happening, but I see the consequences every year, immediately followed by little piles of marten droppings deposited in prominent places on paths, on gateposts, on boulders. They are unmistakable; the berries are only partially digested and clearly pass through the martens at high speed, looking more like a vomited bolus than faeces – a rowan purge. This intriguing behaviour will continue for as long as the berries are available on the trees.

What it suggests to me is that the martens may have difficulty in obtaining as much live mammal prey as they would like. Field vole populations famously soar and then crash. In lean years, the martens may not be able to get as many as they need to supply them with the essential vitamins taken in by the voles’ catholic feed. As Rowan berries are rich in vitamin C, when the autumn bonanza comes along perhaps some curious metabolic alchemy is telling them to gorge while the going is good.

Martens are still limited in their range, but they have spread south and east throughout the Highlands and down into Fife and the Central Belt, even to the outskirts of the great Glasgow conurbation. Here, in these glens of the northern central Highlands, they are now widespread, even common. It is no longer a rare sight to see one dead on the roads – a sure indication of a mobile population currently estimated at between three and four thousand animals. Alicia tells me we have several individual martens occupying our ground on a more or less permanent basis. She gives them names according to the characteristics of their pelage: Spike, Blondie, One Spot, Thumbs, Patch and so on. Some stick around for several years, others seem to disperse quickly, or perhaps get killed off on the roads or by the few people in the glen who don’t like them because, if given half a chance, they will cause mayhem in a hen run. Our resident martens den in the stables roof and occasionally in the lofts of estate cottages and outhouses. I am often amazed by their ability to find a tiny entrance hole, a way in under the eaves. In our hides our field centre guests are happy to sit out the long summer evenings waiting for them to come in to the peanuts and jam we put out.

* * *

It is dawn, the moment in the day I have always loved most. It’s a long standing obsession and it hauls me out, out and about, often doing nothing in particular, just enjoying the lifting light and the world around me pulling on its clothes for the day. September dawns are often still and cool with a tang of freshness all their own. The only bird singing is the robin, tinkling his gentle, melancholic aria that always presages the first light of day.

I have just let out our twenty-five chickens by pulling the cord that lifts their hatch. One by one they tiptoe into the new day with mildly bemused expressions, slightly lost, as though such a thing has never happened before, rather like inexperienced travellers getting off at an unfamiliar railway station. Then something seems to click and they remember where they are and what to do. With a flap and scratch they head straight into pecking mode without any of the wary looking around you might expect of a bird so regularly ravaged by furtive, dawn-slinking predators like the martens. I throw them a scoopful of grain to reward them for their patience.

I walk quickly away from the hens’ paddock and turn up the old avenue of limes and horse chestnuts, picking my way through the prickly shells of fallen conkers on the path. I cross the burn on the little bridge where the water from the high moor, brandy-wine brown, gossips a private conspiracy between mossy stones, hurrying down to join the Beauly River. It is difficult to pass over and I stand on the bridge for a moment or two, smiling inwardly.

Just then I get the overpowering sense that I am not alone. I have experienced it many times before and I’ve long since given up trying to explain it. If it is a sixth sense, I can’t define it beyond observing that it is seldom wrong and I value it greatly. Like a line from a cheap thriller, I feel someone’s eyes drilling into the back of my head. I turn slowly. At first I think I must be mistaken, but then, as pure and shocking as coming downstairs and finding a stranger in your kitchen, our eyes meet. At my eye level and only ten feet away a pine marten, the size of a small cat, is perched upright in the central fork of a rowan tree beside the burn. His black front paws rest on a diagonal stem and his long, elegant tail floats below. He is staring straight at me. I am rooted. How long has he been watching me? Why hasn’t he run away? Why has he let me get so close? What is going on inside that tight little torpedo of a skull?

He is magnificent. His head is angular and pert, a sharp little face reflecting a sharper intelligence within. The ears are small and rounded. His wet nose gleams in the morning light. Dressed in velvet suiting of dark chocolate, a V-shaped bib runs down his chest and between his forelegs, a bib as orange as the filling of a creme egg. A single cocoa spike-shaped smudge at the bottom of his bib gives him away. He is Spike, a full-grown dog marten we know well, a marten with pizzazz, who visits the hides and has been around for a couple of years. Unblinking, his eyes are as bright as polished jet. He doesn’t move.

A pine marten’s life is simple. They are driven by need and fear – those two. Need for food and a mate; fear of man the dread predator, the exterminator. Occasionally a golden eagle, swooping from above will catch a marten out in the open; their remains turn up in eyries from time to time, and just occasionally, very rarely, a marten accidentally gets into a tangle with a badger or a fox or perhaps even an otter, and comes off worst, but man is by far the greatest threat.

So here we are: the man and the marten. I’m glad he doesn’t know that we have persecuted his kind to extermination throughout most of Britain and I’m glad that in this frozen exchange he doesn’t yet see me as so dire a threat as to trigger instant flight. The seconds tick by. My eyes are locked onto his; his onto mine. My brain has emptied down, nothing to offer. For as long as it will last, time has stopped. He is glaring at me like an angry drunk at the other end of the bar, daring me to look away.

Very slowly I withdraw my wits from his demonic, levelled gaze. I know why he is there. It is a rowan tree. It is his time for gorging on berries and he does not like to be disturbed. He has been to the top of the tree and bitten off several weighty bunches of fruit. They lie scattered on the ground between us. He was on his way down to get them, caught in the middle. His dilemma is twofold: to come down for the spoils, or let discretion win and just flee, to leap away through the trees as fleet as a squirrel. If he ventures down to the fallen berries he must come closer to me. If he flees he could be gone in a flash of chocolate fur. He wants his berries. I know that if I move even an inch, he will go. Indecision and indignation have clashed in his taut little marten brain. For the moment it is stalemate.

I have seen martens on countless occasions, far too many encounters to remember any but the most exceptional, but I have never been fixed like this before. It is as though I am no longer in control and I have to wait for his next move. The chess analogy is irresistible. We could be here for a while.

Not in a million years would I have predicted what happened next. I had only foreseen one realistic option: that his nerve would eventually fail and he would turn and vanish into the trees. After all these years of seeing and thinking I knew pine martens, I would have put good money on it. Oh! We are so smug. We gain a little familiarity and a little knowledge and we think we’ve got it sorted. We think that wildlife behaves as it always does, predictable, reliable and you can tempt it in with a bait, trap it, radio-tag it, plot it on a graph and check it all out in a book. Insofar as we’re prepared to concede that other species have intelligence or wills of their own we insist that they are locked within the limitations of their species’ hard-wiring. All we have to do is read the wiring and we’re home and dry. We think we know the pine marten.

I was enjoying this encounter, but the smugness of our own imprinting was wrapping me round like a fog. I fooled myself into thinking my superior brain was back in control. It was just a matter of waiting – yes, a game of who will blink first, and it was I who was in charge. And it would be Spike, as I had determined it must be. But that wasn’t how Spike saw things this morning. It was as though he had sussed that I wasn’t going to give in – had weighed it all up and carefully considered his options.

Without the slightest hint of panic or hurry he turned away and disappeared down the far side of the trunk of the rowan. Ha! I thought, I’ve won. I was wrong. Oh God! I was wrong, wrong, wrong. There was nothing hard-wired about Spike this morning. He appeared again at the foot of the tree and in three quick bounds he came straight towards me. From only five feet away a chittering yell of abuse broke from his throat, hurled at me with all the venom he could muster. Then he snatched up a bunch of berries – his berries – threw me a disdainful glance and vanished back into the undergrowth. Checkmate.

In this charming and profoundly personal celebration of the return of the pine marten, Polly Pullar has provided us with an essential extra dimension to its habits and characteristics – that of people living with martens and other wildlife. It is something us humans are not very good at; our record is dismal. But Polly and her friends demonstrate not just that it is possible to tolerate wildlife in and around our homes, but also that to welcome it, understand it and enjoy it can be an immensely rewarding intellectual and philosophical exercise. It is also vital if we are to protect and maintain wildlife and their habitats for future generations. I salute Polly and her family for their dedication to that wise and vital cause.

John Lister-KayeMay 2018

INTRODUCTION

A brief glimpse

In the still of an evening I sit by the shore as Loch Sunart sways soothingly. I hear the calls of curlews, and the haunting cry of a distant red-throated diver. I watch quietly as a grey seal appears. It is the watched that observes the watcher, as well as the other way around. It is bottling and snorting, in sea that fizzes with drizzle, with a thin, watery rainbow as its backdrop. Salty droplets cling to its whiskered face as it exhales loudly, poking its dark head up even further, the better to see me. Perhaps I may also see an otter. The sun begins to slip reluctantly into its bed far to the west over an ancient swathe of woodland ornate with plant riches, a natural kingdom of immeasurable value. Close by me the tortured form of an oak has pushed its way forth from out of a fissure in a massive barnacle-covered rock cleft. Now almost horizontal, it has been kissed by a thousand sunsets over Mull, Coll and Tiree. It is no less impressive than its gigantic English parkland counterparts. In fact perhaps it is more impressive, tenaciously clutching as it does to succour between a rock and a hard place.

The seal has become bored with me and swum off. I sit a while longer, not wanting to stir; the afternoon is drowsy and peaceful, with only the whisper of a vole in the grasses. Then in my silence I catch a movement. Something brown and exuberant is busy on the edge of my viewpoint. It is darting about as if playing, and momentarily vanishes in the waving flag iris on the shore’s edge. My foot spasms with cramp but I dare not move to rub it. I wait. A male stonechat with his bramble-black eyes and dark hood alights on a foxglove. I raise my binoculars in slow motion, and there behind him is another movement. A curvy form dances out into the open, wearing a coat of mocha colour and a pristine yellow-cream bib. It is playing with something, and then rubbing its elastic body over it. It picks it up in its mouth and throws it into the air, then leaps to catch it before pirouetting onto a rock. It turns and stands silhouetted against the low light – a pine marten with a vole. And then as quickly as it appeared it melts silently into the shadows.

* * *

Fleeting vignettes like this, revealing the life of the pine marten and the creatures that share its habitat, have always absorbed me. I have been fortunate to have developed my life’s passion into my profession, folding the time I spend in the wild into my working life as a writer and photographer, recording many of the wonderful moments I have spent with our country’s precious, diverse wildlife. At home, in Highland Perthshire, my partner Iomhair and I use trail cameras; we have recorded a wonderful range of wildlife that regularly comes to our garden, including pine martens.

The story of the pine marten reveals much about the wildlife of the more remote regions of Scotland; and the observations of an extraordinary, dedicated couple, Les and Chris Humphreys, who have turned their own garden on the shores of Loch Sunart over entirely to martens and a host of other fauna, have opened up fresh insights. Over the past fourteen years, my close friendship with them has added another aspect to my wildlife sojourns in Ardnamurchan – a place that has grounded my passion for the natural world since my early childhood – and given me a unique opportunity, and inspiration, to write about these rarely seen creatures. The Humphreys’ story has over the years merged with mine, and as they would never have written it I have agreed to do so.

As a naturalist, I have learnt that whilst I may set out to look for a particular bird or animal, often I will be side-tracked and absorbed by something different altogether – a swathe of flowers I have never noticed before, the colour and detail of tiny lichens and mosses growing on a stump, the sounds and behaviour of a flock of unusual birds high in a tree, or a place where a badger has been digging out a wasps’ nest, its claw marks scored onto bare earth. Then the journey takes another path altogether as I become eager to discover more. Being side-tracked is integral to watching nature, and therefore, though pine martens form the thread running through this book, the chapters that follow encompass a far wider perspective. My tales largely revolve around the unique Ardnamurchan peninsula and the wealth of its nature in its many moods, but include a few forays to other remote and wind-hewn parts of the Highlands and Islands too.

The pine marten’s collective noun is a ‘richness’, and though the marten is the leading character in my story, the term ‘richness’ also usefully highlights the diversity of my meanderings.

1

Oaks of the western seaboard

When I was seven years old, my parents owned the Kilchoan Hotel in Ardnamurchan. We had moved from rural Cheshire at the end of the 1960s because they wanted a complete change, a new challenge. They were concerned about encroaching development on the Wirral peninsula, and my father was fed up with running an inherited timber business in Liverpool. He was totally unsuited to it, and knew this. They took the plunge and moved to another peninsula – this one Britain’s most westerly. Our lives would never be the same again. They certainly found the challenge they were looking for.

For me as an impressionable, inquisitive tomboy with a mad passion for wildlife right from the outset, our decampment northwest was to prove significant, and gave me the grounding for a love that swiftly became a way of life. Ardnamurchan is at the root of my very being, and its diverse wildlife and wild places quickly forged my burgeoning fascination for the natural world. Soon after we moved I was fortunate to see a host of species I had previously only dreamed of, including wildcat, otter, red deer and golden eagle. And what was more, I saw all of them, with the exception of the wildcat, on an almost daily basis, and even the wildcat was still occasionally seen towards the end of the 1960s, and on into the early 1970s. I became increasingly absorbed and was seldom in the house, even on the wettest days. I feel fortunate that I had parents who understood my need for freedom, and my fascination and love for the wild; my mother’s own childhood in rural England had also been dominated by nature, and my father was fascinated by red deer, their natural history, and the traditions and management surrounding stalking. I could wander almost anywhere I wanted to go and the dangers of the sea, the cliffs, or being lost on the open hill in dense low cloud were things I learnt about very quickly, and grew to respect.

It seems perhaps odd to reflect back and realise that as children growing up in that remote Gaelic-speaking village more than fifty miles from the nearest town, Fort William, no one worried about health and safety issues, and we all made our own entertainment – nature being very much at the heart of the matter – thankfully. It fills me with horror now to think that had I been born half a century later, things might have been very different.

The Corran Ferry, one of few remaining mainland car ferries, traverses the racing currents of Loch Linnhe between Nether Lochaber and Ardgour, providing a vital link to the Ardnamurchan peninsula. A drive from Strontian to the village of Kilchoan, almost at the peninsula’s end, reveals some of the most dramatic oak woodlands in the British Isles. The importance of these woods was finally recognised towards the end of the 1970s, and since then work has continued in an effort to restore and regenerate them back to their former glory.

Gnarled, wind-sculpted and massaged into extraordinary forms by the salt-laden gales that drive in off the Atlantic, the Sunart oak woods are some of the largest surviving remnants of this important type of woodland, and provide vital rich habitat for many creatures, from the smallest invertebrates to the largest mammals. These exceptional woods contour the rugged coastline, their roots spreading far as they struggle to hold tight to thin soils. A scattering of other oak woods of equal importance is found in Knapdale, and Taynish on the Kintyre peninsula, and on Mull and Skye, whilst a few survive further north along the western seaboard, creating a lush pelmet dripping with lichens and polypody ferns where burns tumble down the steep hillsides in their hurry to reach the sea.

In my formative years, when my family lived here, I spent a great deal of my free time wandering in one particular oak wood. I could ride my pony so far along the shore, and then leave him to happily graze on an area of old pastureland whilst I went off on my expeditions into the trees. It is one of the loveliest places I know.

Ben Hiant, roughly translated from the Gaelic as the enchanted mountain, is a small hill that dominates the area. It is but 528 metres high, but despite its size has the strength and character of a far larger mountain. From its steep-cragged summit above the Sound of Mull, the view wanders out to the islands of Mull, Coll, Tiree, Rum, Eigg, Muck, Canna and, on clear days, north to Barra and the Uists. And the sylvan glory of the ancient oak wood that grips its western flank is of unsurpassed quality, the domain of raven, buzzard, eagle, otter and pine marten. I return to this special haunt on a regular basis for it refuels my soul; there is little doubt that those early childhood explorations are embedded in my psyche, and helped inspire my love for the wildness that is Ardnamurchan. Sadly, though largely unaltered over past generations, these oak wood remnants are now heading towards the end of their natural life, and grazing pressures from sheep and deer mean there is little natural regeneration.