Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Birlinn

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

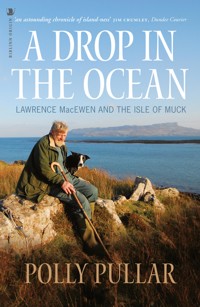

Polly Pullar tells the fascinating tale of one of the Hebrides unique thriving small communities through the colourful anecdotes of Lawrence MacEwen, whose family have owned the island since 1896. A wonderfully benevolent, and eccentric character, his passion and love for the island and its continuing success, has always been of the utmost importance. He has kept diaries all his life and delves deep into them, unveiling a uniquely human story, punctuated with liberal amounts of humour, as well as heart-rending tragedy, always dominated by the vagaries of the sea. Here are tales of coal puffers and livestock transportation on steamers and small boats, extraordinary chance meetings and adventures that eventually led him to finding his wife Jenny, on the island of Soay. It's a book about the small hard-grafting community of 30 souls on this fertile island of just 1500 acres.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 401

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

A DROP IN THE OCEAN

Lawrence MacEwen and the Isle of Muck

Polly Pullar has worked with animals all her life, as a sheep farmer, wildlife guide, field naturalist, photojournalist and wildlife rehabilitator. She writes and illustrates articles for numerous magazines including the Scots Magazine, Scottish Farmer, Tractor and People’s Friend and is currently the wildlife writer for the Scottish Field. She has written a number of books including Dancing with Ospreys, Rural Portraits – Scotland’s Native Farm Animals and Characters, and is co-author of the acclaimed Fauna Scotica: People and Animals in Scotland. She lives in Highland Perthshire.

First published in 2014 byBirlinn LimitedWest Newington House10 Newington RoadEdinburgh EH9 1QS

www.birlinn.co.uk

Copyright © Polly Pullar 2014Foreword copyright © Mark Stephen 2014Black and white photographs reproduced courtesy of the MacEwen family, Clare Walters and the Isle of Muck and Eigg archives.Colour photographs copyright © Polly Pullar.

The moral right of Polly Pullar to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

All rights reserved.No part of this book may be reproduced, stored or transmitted in any form without the express written permission of the publisher.

ISBN 978 1 780127 236 8eISBN 978 0 85790 822 3

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication DataA catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Typeset by Iolaire Typesetting, NewtonmorePrinted and bound by Gutenberg Press, Malta

For my wonderful son Freddy, and for Iomhair, who both made this possible

Polly Pullar

This story is dedicated to my wife, Jenny, who for 30 years has worked tirelessly to build the community on Muck.

Lawrence MacEwen

Contents

List of Illustrations

Acknowledgements

Map

Foreword

A DROP IN THE OCEAN

Lawrence’s Parents

Timeline

The Isle of Muck – a Brief History, According To Lawrence

List of Illustrations

Landing feeding stores from the puffer in Laurie’s launch, 1931

Unloading Coal in the 1940s

Putting cow in sling from Caledonian MacBrayne Steamer, c. 1950

Loading Sheep onto Estate Boat, 1940s

Commander MacEwen

Alasdair, Lawrence, Ewen and Catriona

The Commander, Mrs MacEwen, Alasdair, Lawrence, Catriona and Ewen

Lawrence c. 1960

Shepherd Archie MacKinnon with Alasdair, 1960s

Lawrence and Jenny’s wedding, Soay

Jenny with Colin

Jenny, Mary, Colin, Lawrence and Sarah

Puffer Eilean Easdil at Port Mor

Haymaking at Gallanach, 1970s

Lawrence’s mother in the farmhouse kitchen

2000 Wave arrives in Arisaig with lambs

Gallanach, farm, lodge looking to Eigg

Muck sheep with Rum

Highland mare and foal

Calves with Rum behind

Colin and Ruth’s wedding

Jenny with Mattie, April 2014

Amy waiting for the ferry

Coming off Lamb Island

Lawrence in the byre door

Lawrence with his beloved Fergie and beloved cows

Lawrence feeding ewes, 2014

Lawrence with Molly

Ruth and Hugh

Muck school with teacher Liz Boden and islanders doing litter pick

View from Beinn Airean

The Bronze Age Circle and MacEwen Grave with Rum behind

Rainbows over Gallanach

Camus Mor

Acknowledgements

Firstly, I want to thank Freddy and Iomhair for their advice, enthusiasm, invaluable input, patience and support.

Sincere thanks and gratitude go to the Society of Authors; in particular, the Authors’ Foundation and K. Blundell Trust for their generous help with this venture. Also to Caledonian MacBrayne, for support and sponsorship.

Special thanks to Mark Stephen for his incredible encouragement and enthusiasm, and to Debs Warner, who has done a wonderful job with the editing and made so many hugely helpful suggestions.

Further thanks go to the following: Jenny MacEwen, for putting up with it all, and for providing endless sustenance and advice; Ruth and Colin MacEwen, for their generosity in lending me Gallanach and Seilachan cottages – perfect places to find peace and creativity – and also for rooting out photographs and newspaper cuttings.

To Clare Walters, for her time, stories and photographs; Zoe Moffat, for her creative input and hard work to produce the map; Dougie Irving, the itinerant dyker, whose input was hugely appreciated; Mary and Toby Fichtner-Irvine, for their support, and for doing a great deal of printing; Sarah Maitland MacRae, for photographs and general help; Julie MacFadzean, for meals, kindness and accommodation; Dave Barnden, for his well-timed Rusty Nail, and his encouragement and general unsurpassed support; Sandra Mathers, for extremely wise advice; Sandy Mathers, for fixing the door; Ewen Bowman, for really great craic; Cathy Vaas, for her help and comments; Ewen MacEwen, for kindly rooting out the missing diaries; Richard Bath of Scottish Field magazine, for the inaugural trip that sowed the seed; Molly Fitch, for archive images; and to Ian McCrorie, Les and Chris Humphreys, Fiona MacEwen, Ian Bell and Martin Beard. And to wee Willow Moffat, for her effusive welcomes at the pier.

Finally, thanks to the maestro: father, grandfather, farmer, forester, retired coastguard and Special Constable, Muck ambassador, unofficial grave digger, master of ceremonies, etc. dear Lawrence, who has been such a joy to work with and who ironically does not seem to think he has the ‘MacEwen’ determination. If this were not the case, then this story would never have been told.

Polly Pullar

Many islanders appear in the text and need no mention here, but there is another group of people who played a vital part in running the farm and have received scant attention: the students. First fed and watered by my mother, and later by Jenny, it is my hope that they left this island with experiences that will serve them well for the rest of their lives: James Alexander, Alec Boden, Charles Blundell, Jamie Brett, Nicki Brett, Lucas Chapman, Peter Douglas, Duncan Geddes, Alan MacBroom, Donald John MacDonald, Calum MacRae, Helen Nimmo Smith, John Slater, Kate Sutton, John Symon, Andrew Todd, Miles Tompothelthwaite, Mark Wang, Simon Ward, Andrew Watts, Philip Watts, Adrian and Justin. And, from Switzerland, Anna, Florian, Lorenz, Mitja and Roger.

Lawrence MacEwen

Map

Copyright © Zoe Moffat

Foreword

All islands suffer from a sort of romantic overlay, the application of a heedrum-hodrum filter that softens the edges, prettifies the reality and disguises all warts or blemishes; it’s a sort of geographical beer-goggles. That’s what makes writing about Muck so difficult. Muck is one of the smaller Small Isles, the others being Rum, Canna and Eigg.

The problem with writing about Muck is this. The light here is actually diffuse, naturally soft-focus; you’re not imagining it, that’s the way it is. It is beautiful, the views from it are superb and it’s a haven for wildlife – last night I stood under the thinnest of fingernail moons listening to snipe drumming in the dark, while geese grumbled and squeaked in the field above me and seals sang in the bay. Muck is no Shangri-La, but the folk here seem, on the whole, pretty happy and content. There is new building going on, children playing, projects being planned; a real sense of purpose. The houses are lived-in, worked from. This island has managed to avoid the pernicious spread of holiday homes that has hollowed out so many other west coast communities. The land is fertile and in good heart, the fields have that groomed look usually associated with the wealthier mainland farms, boggy sections and rushes are at a minimum. The sheep, cattle and ponies are all breeds that fit well into the landscape and thrive here naturally.

Much of this is due to the man who, together with his family, owns the island: Lawrence MacEwen.

If anyone ever gave Lawrence the manual on ‘How to Be a Landowner’, I can only assume that he used it to catch oil drips from his beloved vintage tractor; he certainly never read it. On the telephone you might mistake Lawrence for a toff – those gentlemanly Gordonstoun-trained vowels, the measured statements, the reflective pauses. In the flesh he looks like an elderly Viking jarl, cast out of time and into a boiler suit and wellies. His body is bent with 60 years of hard labour; his huge hands are maps of the island, the contour lines drawn deep into his flesh with soil and lanolin. A gentle man, he seems as comfortable hand-milking cows as he is playing with his grandchildren or chatting to his neighbours.

This is a man who dearly loves his flocks, both animal and human.

He is modest, hugely knowledgeable and undoubtedly infuriating to his family, who probably wish that he would act his age and stop being so bloody outspoken. He is a fount of stories, a few of which cannot be included or else they might land author Polly Pullar in court for years to come.

(In fairness, having described Lawrence I should also describe Polly.)

A slim, attractive redhead with a depressing ability to outrace larger, stronger men on the hill – I speak as one of those men – Polly is a countrywoman to her bones, curious about all things and closely familiar with plants, birds and animals. And she has a rare gift. She can listen, really listen, to what people are saying, their stories, memories and anecdotes. Her genuine admiration and respect for the storytellers shines through and, like a glass lens on a sunny summer’s day, she focuses each tale to a point of brightness and helps warm it, bring it to life. Her extensive bibliography and the respect in which she is held by country folk speak for themselves.

Scotland is fortunate to have people like Lawrence and Polly, but doubly so now that they have come together. It was a pleasure watching them work on this project; it seemed to me to be more than a friendship, something more akin to a father/daughter relationship.

It may seem to you, on reading this, that Polly will have, must have, fallen into the classic Brigadoon trap I mentioned earlier, painting a man and his island, and its people, with a shortbread-tin gloss. She hasn’t. Yes, there are lives and experiences on these pages to envy, much to smile or laugh at, but this book also makes it abundantly clear that nobody ‘escapes’ to an island. If you have problems in the Home Counties, you’ll still have them here, and if anything they’ll be even more noticeable.

Polly has produced an extraordinary, unique portrait of a quirky, hard-working, fun-loving community and its democratically minded leader, who hates being called ‘the Laird’. It’s a fascinating, at times sad and frequently hilarious tale, as well as a valuable instalment in Scotland’s social history.

These are folk who voted for a less reliable ferry service so that the best view on the island wouldn’t be ruined: a generous, friendly un-clannish clan, constantly on the hunt for new members.

Can life on Muck really be like this? Well, on the basis of an admittedly brief acquaintance, I think so, but please don’t take my word for it, visit for yourself.

It’s two hours by ferry, but the scones alone are worth it and you can sing back at the seals if you want to . . . I did.

Mark Stephen, presenter of BBC Radio Scotland’s Out of DoorsIsle of Muck,Spring 2014

A Drop in the Ocean

A watercolour painting hangs above my bed. A treasured possession, it depicts a Hebridean shoreline: turquoise, black, grey and moody, a surging sea with foaming waves leads the eye to the distinct shapes of Rum’s forbidding peaks. In the foreground there is another island. Muck, a place that has punctuated my thoughts since I was a child growing up on Britain’s most westerly mainland peninsula, Ardnamurchan.

Whilst wandering at Achateny beach, looking for otters, I often sat daydreaming on a rock, gazing out to the islands as rain fell fizz-like on sea the colour of pewter, or clouds chased one another across an azure sky over Rum’s Askival, Sgùrr nan Gillean and Hallival, the nearby Sgùrr of Eigg, and the distinctive Cuillin Ridge on Skye. Muck, approximately six miles by sea from Ardnamurchan: it came and went through the weather, so near yet so far. Its name and erratic moods fascinated me.

From Ardnamurchan’s north coast, Muck’s outline is often a silhouette, akin to the shape of a melting iceberg. Its highest hill, Beinn Airein, just 451 feet, and the steep sea-girt cliffs bordering its southern coast, appear prow-like.

Other than a brief foray in my stepfather’s boat at the beginning of the 1970s, Muck remained largely a figment of my imagination. I knew so little, yet it is a fascinating place, with a passionate story. When I found myself there by sheer chance on a working mission, I lingered an extra day and fell heavily under the island’s spell and the ethos of its owners, the MacEwen family. That extra day was dismal: I endured the kind of rain that assures thankfully that the west coast of Scotland will never compete with a Spanish holiday resort. The horizontal rain seeps right into the skin, laying waste to the finest outdoor clothing on earth. And it was cold, too. I wanted to spend some time with the island’s owner, Lawrence MacEwen, a familiar name in farming circles, a man who has gained the greatest respect, a true countryman, an eccentric and benevolent character, and most importantly someone who, with his incredible wife Jenny, has been largely responsible for making Muck and its small community the success it is.

My photography work for Scottish Field magazine the previous day had thoroughly whetted my appetite for life on Muck. There had been a shoot, and an encompassing involvement from the islanders, including most of the children, something seldom seen elsewhere. The pheasant, partridge and duck shoot on Muck is a relatively new venture and the visiting guns told me that the event is unsurpassed; fabulous sport, fabulous home-produced food and great craic, so much so that they plan to make the foray an annual event. I had witnessed that camaraderie myself.

I briefly chatted with Lawrence and liked him instantly. We had quickly found common ground – a shared passion for hill farming and native breeds. Sheep have opened many doors for me, and once again they quickly did so. We passed a cheery morning gathering and then dosing and marking ewes in the fank in one of the sheds, while the rain battered the roofs with a vengeance. Following soup with Jenny, he took me on an island tour. It was not the best day for this, yet it mattered not; his stories were fascinating.

At one mile by two, and with only a short stretch of road, Muck may be small but it has plenty to offer. When I left in a worsening gale next morning, I couldn’t decide whether it was actually harder to leave or be stranded. If the forecast was accurate, then this was going to be the last trip for a few days for Ronnie Dyer, the skipper of the Sheerwater. I was already secretly planning my next visit. Over the following months, there were several.

It was a day of squalls lavished with brilliant shafts of low autumn sun. Fulmars flew low over the swell, waves massaged long wings and rainbows momentarily painted dark clouds with hope. From Arisaig, the crossing to Muck in the Sheerwater takes approximately two hours. It’s a turus mara – a sea journey – of heart-stopping beauty, as the play of light on the islands is sometimes almost too much for the human soul to bear.

The boat stops briefly at Eigg – if Ronnie has not been sidetracked en route by his passion for cetaceans, then passengers can land for half an hour. In summer, he frequently runs a little late. A minke whale is spotted. He prides himself on getting his passengers up close enough so that they may even smell the cabbage-like breath of a breaching whale. He may point out a pomarine skua, or some common dolphin; this journey is as much about wildlife as it is about reaching island destinations.

Eigg was a bustle of activity – asthmatic Land Rovers and a throng of islanders met new arrivals, as backpack-clad tourists stepped ashore to be sniffed at by wagging collies. A bossily bristling Jack Russell terrier endeavoured unsuccessfully to mount a flirtatious collie bitch, then defiantly hupped his leg onto an unattended suitcase instead. There were reunions and new meetings, hugs and handshakes, laughing voices; everyone dived in to sort out provisions, luggage and supplies, from light bulbs to loo paper, spanners to sugar. Sheerwater and Caledonian MacBrayne’s Loch Nevis are lifelines. Boat arrivals are a social occasion, a gathering of long-awaited booty amidst a haze of revelry, and perhaps the aromatic whiff of wacky baccy.

We headed for Muck. The sea had turned inky blue-black, a storm cloud hid Eigg’s craggy sgùrr; a venomous shower was burdened with hail. The channel into Muck’s new pier is tricky. In severe weather and difficult tides, the small Sheerwater can often manage when the larger Caledonian MacBrayne boat cannot. Ronnie is intrepid but never puts his passengers at risk; Muck can be cut off for long periods.

Muck’s pier also buzzed with activity. Bedraggled dogs and antiquated vehicles were gathered. Unlike Eigg, on Muck bitches are sensibly the only resident canines, so avoiding unwanted pregnancies, hassles and heartbreaks. Small rosy-cheeked children raced about on bikes. In the midst of the melee stood Lawrence, a man entering his early 70s. He was chatting, slightly stooped. Like the island’s small trees, he appears almost wind-sculpted by the prevailing gales, honed by years of sheer hard graft and the vagaries of the climate, still handsome. Clad in a boiler suit and wearing yellow oil rig-style wellies (and usually no socks), this is no tweedy absentee landowner but a driven soul who participates in everything from farming to his grandchildren’s tea parties, from drain clearance to butchering pigs, from holding business meetings to biking off to meet new arrivals at the pier. He and Jenny have always worked interminably long days and seem to be everywhere all the time for everyone.

Lawrence MacEwen is, in fact, the laird of Muck, but you would never think it. A distinctive figure with incredible blue eyes and bushy ginger eyebrows, a shock of greying, blond hair and a ginger beard, some describe him as like a noble Viking. He smiled, as huge work-hardened hands warmly shook mine. Soon my belongings and provisions were loaded into the transport box of his vintage Ferguson tractor, together with me and my collie, and it spluttered into life, carrying us in style to our accommodation. Two island collies galloped beside us, as the reek from the tractor dispersed and we gently proceeded along Muck’s highway – just a mile of tarmac with a grassy fringe down its centre. The squalls had calmed, the air was sharp, clearing from the west. Rum looked spectacular.

At the end of the road, my chauffeur barrowed my belongings from the farm up a narrow path around the bay to an airy cliff-top cottage overlooking a view to die for. We chatted about the price of sheep, the forthcoming cattle sale in Fort William and the final electrification of Muck. Despite a dodgy knee and a painful limp, he was insistent on pushing the heavy load. As I was about to discover, it is this very dogged determination that has kept this man at the helm of Muck for all these years. I had arrived and was now starting a journey with one of the most extraordinary people I have ever met. Lawrence MacEwen’s story, the story of the remote Hebridean island of Muck, was about to unfold.

Muck, like all Hebridean islands, has a character all of its own. It’s part of a group known as the Small Isles which, though they may be relatively close to one another, all have a very different tale to tell: Eigg, with its chequered history of difficult landowners, is now owned by the community; Rum, a National Nature Reserve, with its minutely studied red deer population, is owned by Scottish Natural Heritage, as well as the local community; Canna, a farming isle bequeathed to the National Trust for Scotland by the Gaelic scholar John Lorne Campbell; and Muck, owned by the MacEwen family since 1896, the smallest and most fertile.

Muck is approximately 1,500 acres and has always had an excellent farming enterprise. The MacEwens are born stockmen and have farmed with the elements rather than against them, choosing highly suited native breeds with infusions of other blood to produce prime livestock. The good grazing supports 600 ewes, predominately dark-fleeced Jacob-Cheviot, plus 40 Luing and Luing-cross cattle. Recently Lawrence handed over the farm to his son, Colin, a man infused with the same MacEwen work ethic, and his equally hard-working wife, Ruth. Muck can produce surprisingly good crops, and over the years haymaking has been an important part of the agricultural calendar, though in recent increasingly wet summers silage has proved a less stressful option. Many of the island’s ancient drystone dykes have been recently rebuilt, adding greatly to the landscape features. There has been some new building – a new guesthouse/shooting lodge and a smart new community centre – and there are usually about eight children in a fairly modern school. The island population is currently around the 40 mark. Small woods planted since the mid-1900s have stood the abuse hurled at them by the climate, and have miraculously survived, providing vital shelter for birds and beasts.

The MacEwens made two smallholdings to accommodate the islanders, but Muck is not honeycombed with crofts; Lawrence and his family are about as far removed from the archetypal ‘feudal laird’ mould as it is possible to be, but their leadership and guidance has greatly helped the island’s stability. Despite this, problems and tragedies have been aplenty, some of them so heartbreaking and hard to deal with that they have doubtlessly led to a deep inner sadness.

In savage weather Muck can be one of the hardest places to live, but on days when sky and sea are as blue as topaz, and the bogs are red and emerald green with verdant mosses spiked with the delicately green-veined white waxy flowers of Grass of Parnassus, and the curlew calls over the sandy beaches, it is also heaven on earth. The flora and fauna of Muck is richly varied. In spring bluebells carpet the small woods and grassy banks, and stunted orchids dot bog and headland, while snipe drum high in the sky serenaded by cuckoo, skylark and a host of newly arrived migrants. In the sheltered bays the amorous cooings of dapper pied eider drakes posing to prospective mates also heralds the beginning of another busy tourist season. Though the wildlife is varied, there are few land mammals – otters are occasionally seen, common seals are numerous and haul out onto the skerries at Gallanach every day, and some grey seals come ashore to breed on Horse Island in the autumn. Their melancholy singing mingles with the wind and on moonlit nights adds an eerie dimension to the backdrop of silhouetted islands. Whales, in particular the minke, basking sharks, dolphins and porpoises can also be seen. It has been suggested that the Gaelic name for porpoise – muc mara, sea pig – is perhaps the origin of the island’s name. Both golden and sea eagles appear, though do not nest, on Muck. During one particular stay at Gallanach Cottage, a young sea eagle passed several times each day, sweeping so low and close around the headland that the sky noticeably darkened. I stood in a garden vibrant with fuschias and montbretia and watched it drift over in the direction of the duck pond – sea eagles are lazy hunters; it had clearly learned that an easy takeaway could be found courtesy of the Muck shoot. Toby Fichtner-Irvine, husband of the MacEwens’ daughter Mary, who runs the shoot, was philosophical about it: ‘The visitors will love it and I am sure we can spare a few duck and partridge for the sea eagle.’ Nature is quick to take advantage. Peregrines, too, were a daily sight and I found a plucking post on a prominent rock near the shore, with remnants of rock pipit’s feathers. Since the advent of the shoot and the arrival of numerous game birds, and the associated feeding of grain, numbers of passerines have increased dramatically, but so too have the rats. Occasional passing rarities cause a flurry of excitement, as ‘twitchers’ flock from near and far to add another tick to their lists, despite the logistics of the journey. As Lawrence wryly put it: ‘When we had a very nondescript bird, a veery, a North America member of the thrush family, hanging around the silage pit, they came in droves and stood there with telescopes and massive lenses – I suppose they must record it on Twitter.’

Muck has never had a shop or post office. There is no doctor or nurse, and until 2013 there was no round-the-clock electricity. In fact, it was one of the last places in the UK to be electrified. Jenny MacEwen, who Lawrence describes as the ‘human side of Muck’, runs a thriving tearoom; it bulges at the seams in summer with day-trippers calling in on either of the two boats. Island fisherman Sandy Mathers, one of few remaining residents bred here, keeps her stocked with shellfish. She is up at dawn baking delicious bread and cakes, as well as vast vats of soup with home-produced ingredients. Many visitors will walk no further than the tearoom close to the pier and, satiated with Muck’s fine fodder, leave to tell friends and family how lovely it all is, though relatively they will have seen nothing.

Muck, like neighbouring Rum and Ardnamurchan, is important geologically and is largely composed of basalt lava flows. The dramatic shoreline and cliffs at Camus Mor on the island’s south-west side are a Site of Special Scientific Interest; fossils found here are confined to stunted oysters forming layers amongst other material. Surrounded by a dramatic panorama of islands, views sweep to the rugged hills of Knoydart, Torridon and Ardnamurchan Point; this tiny drop in the ocean captivates all who visit but not only for the scenery, flora, fauna and peace.

Growing Up on Muck

Lawrence’s debut on the island was perhaps a little unceremonious. In July 1941, when Mrs MacEwen was returning from hospital to Muck with the latest addition to her family, she travelled as usual from Mallaig on the Loch Mhor, skippered by the well-respected and fearless West Highlander Captain ‘Squeaky’ Robertson. He descended from the bridge with aplomb and greeted her whilst peering into the Moses basket, where the new infant was lying peacefully. ‘Ah, Mrs MacEwen,’ he said smiling broadly, ‘he looks chust like a boiled lobster.’

The second of four children, Lawrence, due to the age gap, was closest to his late brother Alasdair. Catriona and Ewen are respectively three and five years younger.

‘In the beginning, Mother was running the farm, as Father was in Shetland, where he would have been having a relatively cushy time looking after the harbour in Lerwick; Mother had a lot to do. Father had Wrens to iron his shirts, while Mother had to look after us hooligans, as well as doing the farm. Father did send a naval rating over to help us, who had come from a Lewis croft, so he was quite good – he used to carve us little wooden boats as well. I suppose at that stage there was no paperwork on the farm and you just had to look after the livestock. She had quite a reasonable staff, as agriculture was still important: if you were working in that line, you weren’t called up. Sometimes I remember, she sent some washing over to a Mrs Campbell, who was a washerwoman on Eigg, though it was just linen, as a note from her read, “No body clothes.”

‘During the war, even Muck had a blackout, though we must have been well out of range. However, it was important that the German bombers would not see us. They reached as far as Fort William and dropped a few bombs there. We only had double burner lamps, which hardly gave any light, but even with these insignificant lights we were supposed to have brown paper over all the windows. Then we had ration books with vouchers valid for the Co-op in Eigg; it was amazing how well we all survived on hardly any food. Not everything was rationed, but to acquire most items little squares were torn from a ration book. We were fortunate to be fairly self-sufficient. We had our own meat on the farm, and eggs. In fact, we used to sell the latter on the black market in Tobermory and got paid a good price for them. Driftwood often used to wash up on the shore and this was a big thing for us in the war. The Atlantic was rife with German U-boats busy sinking merchant ships by the dozen, so deck cargos of timber from Canada and all sorts of other treasure came ashore. The MacDonald family, who lived in Pier House, always kept watch and patrolled around the shores day and night with hurricane lamps. Timber was piled high on the shore, but sometimes amongst it bodies were found – two were British and had come from HMSCuracoa. It had been hit by the Queen Mary in fog and was literally cut in half; it was a huge tragedy, with over 350 killed, though it was all hushed up at the time. There were two Germans from a submarine and their bodies were transferred from a grave in Muck and eventually in the 1980s sent down to Cannock Chase, but the British are still up there in the graveyard.

‘One of my early memories is of a mine going off. There were extensive minefields between Scotland and Iceland. Six mines came ashore and one appeared into Port; everyone was very frightened. There was no telephone at that time and only a weekly boat, so forms had to be filled in and sent off so that eventually the mine disposal team came out in a Motor Launch, an ML, and disposed of it. I remember being very impressed by them, as they had all sorts of shiny things hanging from the belts on their uniforms. I was with Father when one mine went off. There was a huge bang, but no one was hurt. Once a bit of mine casing hit a tup and killed the poor beast.

‘Right at the end of the war we had a bit of excitement when Alick MacDonald, one of the men who worked on the farm, came rushing over to tell Mother that there was a raft coming ashore. We were eating our revolting porridge at the time – during the war the oatmeal was really horrid. We raced out and saw this square raft coming into Gallanach. I would have been about four. We gingerly explored it and found tins of wonderful ship’s biscuits. Alasdair got an anchor and tied the raft to the shore, but the rope was rotten and eventually after only a few days it floated off again.

‘In 1947, two major events took place. First, a tractor arrived. It totally transformed farm life. It was a grey Fergie TE20 and we still have it. Our son Colin tried unsuccessfully to get it going again when he was about ten. It arrived on top of a load of coal on the puffer. Father drove it off the pier because Alick, the farm steward at the time, was not very good with machinery and had tried to dance up and down on the clutch; Charlie, who also worked on the farm, managed it no problem. Sadly, the tractor meant that most of our five workhorses were replaced, though we still had Dan, a pure Clydesdale, and Dick, a Highland Clydesdale cross.

‘We shared a load of coal with Kilchoan in Ardnamurchan; the puffer always went there first so that some of the coal had been offloaded. We tried to arrange for her to come in during spring tides at high water and then she could sit grounded all day whilst we unloaded the coal. If the flat-bottomed puffer was too heavily laden, she would be too low in the water even at high tide and would ground astern. Ideally for Muck we needed a boat that was no bigger than 180 tonnes. As the weight in a puffer tended to be all in the stern anyway, it was important that there was enough left in the bow to ensure that, as it came into Port, it could cope with the shallow water and get alongside the pier to unload. Shovelling the huge pieces of coal into a five hundredweight bucket was hard work.

‘The second momentous thing to happen in 1947 was school. Mother had taught us a reasonable amount of reading and writing, and even a little French. She used to draw little pictures to illustrate new words – I remember la maison and the picture of a house. But she could not illustrate the important things, such as the verbs to be and to have, and we all got totally bored with it. I was never any good at French. School was in Port Mor – we usually walked there barefoot in spring and summer. It began in earnest in January, but by February 1947 we were experiencing one of the coldest spells we ever had. I remember walking to Port and sadly finding lots of dead curlews on the track. We never had bikes then because the road was so rough, with large potholes, and our parents were clearly worried about us falling off and damaging ourselves. Soon after this we all developed scarlet fever and were in bed for weeks, so that put paid to school.

‘School really was so boring. We had a reader, and a jotter that we had to fill with “pot hooks” – these are lines and lines of tedious curves supposed to teach good handwriting. Goodness, it never worked for me, unlike Father who had super copperplate-type writing. When things got tough at school, one of the problems was the teacher’s son, Francis MacLeod. Needless to say, he really did not have much respect for his poor mother; he was not a bad boy, but he and I used to gang up on poor Alasdair, who was a very good boy by comparison. We used to call the teacher Mrs Mouse. When we got fed up with lessons, we just got her to read to us. The book I remember most was about whaling, The Cruise of the Cachalot. To begin with, school was just from nine till noon. Mrs MacLeod complained she did not have enough time to teach us so it was extended. Then we had to take our lunch and I really did not enjoy being there for a longer time each day. We had dip pens with inkwells and they were horrid, as they were so messy. When we were at school till early afternoon, Mother was pleased if we did not arrive back till about five because if we were out of sight we were out of mind. After we left the school we went off on wee expeditions and Francis sometimes came with us. He seemed to have access to boxes of matches and we loved lighting little fires in the heather, and occasionally did this in the lunch hour, too.

‘The island had no telephone or radios at that time. If someone took ill and our boat was away, it could be quite serious. Father had arranged that if there was an emergency we would light a fire as a beacon on the island and then help would come from Eigg. It was a good system. The post office was on Eigg, and if we had an important telegram they would light a fire there and we would see it and go over to collect it in the island boat. Father used to be away collecting telegrams quite often, and even more so between the two wars, when he had his own private yacht. With his naval background, he was a very competent sailor.

‘Anyway, we lit this fire during lunch and it rather took off. It was spotted and caused mayhem. Then the Eigg boat, the Dido, came over to the bay. Well, by the time we got back home to Gallanach, Father was waiting for us, looking furious, and he had a bunch of birch twigs in his hand. We really thought we were going to get a beating. Miraculously, he seemed to accept all the excuses we made about not knowing about that system and we had a very narrow escape.’

Another fire adventure could have been far more serious. Leaving school one day, the children went off towards Camus Mor and found another good place for some pyrotechnics, lighting heather growing in an old ruin. There was something wooden sticking out and after a few minutes there was a loud bang. They panicked, thinking it was a gun belonging to Charlie. It turned out that Hector and Charlie had stored a box of detonators there that had washed ashore and they were letting them off by degrees when the coast was clear.

The freedom of Muck provided the ‘feral’ MacEwen children with an idyllic childhood: running barefoot all summer, toes were frequently bashed on the rocks but their feet soon became hardened. In winter they wore tacketty boots.

‘We used to escape to go camping and sneaked out of one of the windows after bedtime. We would take quilts from the house, lowering them out. We did have a ground sheet, but I cannot say it was a formula for a good night. Sometimes we slept under a big rock known as Pug’s cave – it was a tight fit, but we were very small and somehow managed to wriggle our way in. Our parents must have known, but they just let us go – probably because they knew how tired we would be from lack of sleep: it was funny how we could never do it two nights on the trot. We never got into too much trouble and often would camp under just one quilt together.

‘Picnics were the great thing and Mother was very keen on them. We had excursions all around the island, particularly on Sundays, when we would gather driftwood.’

Mrs MacEwen’s hayfield teas were also famous. She made large batches of scones and cut them into four, covering them in jam or cheese and tying it up in a clean dishtowel to take out to the fields together with a large kettle of tea. Lawrence remembers Ewen being in the pram in the hayfield as his mother came out and how she always made special tea for her husband, as he did not like tea so strong that the spoon stood up in it. She was always adamant that the men got their tea before anyone else; the children worried that there would not be any scones left for them, especially the jammy ones. Mrs MacEwen appears to have been the farmer for much of the time and she always ensured that she looked after the workers – an important trait she clearly instilled in Lawrence and his brothers and sister from a young age.

When Lawrence was only 11, already a daring maverick and showing his leadership skills, he decided to scale the craggiest cliff face of Ben Airein with his eight-year-old sister Catriona. His brother Alasdair had gone to prep school, so he had no one to keep him under control. It is an impressive cliff face even for a seasoned climber. They clung onto the rock and heather for grim death. Lawrence, being scared of heights, looked down at his sister and kindly asked if she was all right. ‘Of course I am,’ she replied crossly. ‘Now, hurry up and get on with it, will you?’ She was clearly not suffering from vertigo as he was. Once he reached the top, he raced away from the edge and collapsed on the grass, so relieved to have achieved it. Led by her unruly brothers, Catriona was a tomboy whom they nicknamed ‘Girl’.

Collecting aluminium fishing floats from the shore provided the children with a source of pocket money, for they could get half a crown for a good one and even a shilling for one in less than perfect condition. They wandered around the coast looking for them and when they had enough they were sent to Mallaig, where Willie Fyall from St Monans, in Fife, collected them. Once, their mother took them over to Ardnamurchan for a few days’ camping and Lawrence remembers how much he enjoyed it; they had found plenty of floats there, though it was almost impossible to carry them. They would also go over to collect floats on Rum; the south-west side at Papadil was the best.

There would be plenty of opportunities for swimming, and when they were still very young they all climbed Askival and Sgùrr nan Gillean on Rum, despite Lawrence’s fear of heights. Their mother loved brambles and, though at that time there were few growing on Muck, they would sometimes go with a load of lambs en route to the mainland and get dropped off on Eigg, where they were plentiful, then the boat would collect them on its way home.

‘Another thing I spent a great deal of time doing was watching the tide in the evenings. None of the others did it, but I would stand for hours just glued to it, particularly as it was coming in during spring tides. I was totally mesmerised by it. Mother would eventually shout and tell me it was teatime and I would drag myself away. I now ask myself, was this the equivalent of Facebook or PlayStations? I suppose it was, though I cannot help thinking it was a bit more useful. Alasdair’s great passion was naval history and when we went to bed he would regale me with all this. Looking back, it is quite amazing how much he knew even for just a wee boy. Of course it just went in one ear and out the other, at least most of it did. I was always thinking about farming, even then.

‘I remember we could earn pocket money by helping to carry the thrashed straw to the stirks in their sheds. It was un-baled and was very bulky, and we heaved it up in a big hessian sheet; it was very heavy for us. Father paid me 1s per day and I subcontracted this out to Catriona for 3d and Ewen for 2d. We also had to bed the pens with straw chaff as well. The cattle were fed linseed cake and bruised oats; Ewen could carry buckets of this, as it was not too heavy, and he was just big enough to fill the troughs. Catriona liked climbing up on the hay. She was very acrobatic and used to hang by her legs from the beams, sometimes with a 20-foot drop below her.

‘As Alasdair had been sent away to boarding school and could no longer accompany father, the perks of the job for me were to go with him to the Oban sales – I loved this and went for two years before I too was sent away.’

Lawrence’s first trip away from Muck was to the Salen Show on Mull when he was just seven. It was there, in the streets of Tobermory, that he first saw cars. He and his father stayed at the Western Isles Hotel, overlooking the bay. The best part of this was that at dinner there was ice cream, a treat that Lawrence clearly remembers.

‘I used to think about the ice cream – and sausages, too – for weeks before we went, as these were things we seldom had at home. We would stay in the hotel and then early next day set sail again, heading for the show with the sheep in the boat. We went straight to a private pier owned by a Miss Heriot-Maitland. There we offloaded the sheep and then drove them about a quarter of a mile to the show. We sometimes did very well, but there was staunch competition from Boots the Chemists, who owned Ardnamurchan Estate; the Department of Agriculture, who owned Glen Forsa on Mull; and another big Mull estate, Killiechroanan.

‘One year, I remember there was an announcement over the tannoy. We were all busy with the bustle of the show and this voice said: “Could the parents of Ian Clifton please come to the secretary’s tent, as he is about to cry?” One of our friends who had come with us was very inquisitive and rushed over to see the distraught little boy. When she got there, she found our poor little brother Ewen, who we had not even noticed was missing. Of course he must have been upset and, as he was on the verge of tears, they had misheard his name as he had tried to pronounce his first two names, Ewen Christopher. It was so funny.’

Though the MacEwens loved showing, the logistics of getting animals on and off the island by boat made it a serious challenge, particularly as the weather so often spoilt plans. However, Lawrence’s early determination and tenacity, which some describe as foolhardiness, have meant that he has defied all odds on numerous occasions and got beasts to their destinations come hell and high water, often in the most dubious conditions.

The houses on Muck were sadly wanting. In 1951 under a special Hill Farming Scheme to help modernise facilities and boost productivity for farmers, all the dwellings on Muck were finally given a makeover. Until that time most had not had running water or inside toilets; the women had carried all their water from wells at Port. Rayburns that ran continuously and heated the water were fitted and were a major advance on the ancient ‘black’ stoves. A new house was also built, with materials arriving precariously by puffer. Not surprisingly some of the builders were cowboys; the island was full of Glaswegians who stayed in huts and ate in the bothy, where Jessie MacDonald cooked for them. However, a three-ton lorry brought to help soon expired and clearly could not tolerate Muck’s terrible road.

‘I remember watching all this stuff arriving on puffers and being very excited about it. I was so naive then. The contractor was called Spiers, Dick and Smith and as they had put in a tender of £17,000 – £10,000 below their nearest rival – it is hardly surprising that they cut a few corners. Poor Charlie MacDonald spent the next ten years rectifying all the botched jobs but never complained about it until finally the builders had all gone. I suppose he did get a good new house out of it; he had lived in a tin shed up to that point.’

Stealing My Own Chocolate

Lawrence’s school years were not particularly happy. He was sent to boarding school at Aberlour when he was 12 and felt like a fish out of water. It was all a far cry from the freedom of his island home. Lining up to have hands and shoes inspected before meals and not being able to chat after lights out, to say nothing of the strict regime, went against the grain for a child who was as wild as the wind that frequently swept over Muck. Lawrence, who was already mad on farming, quickly made friends with other farmers’ sons; Martin Weir from Loch Fyne became his best friend, and they at least chatted about the things they loved. When Lawrence bumped into him many years later in Mallaig, he was shattered to find out that Martin was a sales rep for a biscuit company and not a farmer. He explained that poor health had prevented him from following his chosen career.

One of many attributes that I recognised in Lawrence very early on in our friendship is the fact that, though he may be very stubborn, he is an incredibly fair person. However, at prep school one particular incident seemed so unfair to him that he has never forgotten it.