Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Birlinn

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

'Peppered with humour, empathy and kindness' - Sunday Post Ever since her pet sheep Lulu accompanied her to school at the age of seven, animals and nature have been at the heart of Polly Pullar's world. Growing up in a remote corner of the Scottish West Highlands, she roamed freely through the spectacular countryside and met her first otters, seals, eagles and wildcats. But an otherwise idyllic childhood was marred by family secrets which ultimately turned to tragedy. Following the suicide of her alcoholic father and the deterioration of her relationship with her mother, as well as the break-up of her own marriage, Polly rebuilt her life, earning a reputation as a wildlife expert and rehabilitator, journalist and photographer. This is her extraordinary, inspirational story. Written with compassion, humour and optimism, Polly reflects on how her love of the natural world has helped her find the strength to forgive and understand her parents, and to find an equilibrium.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 432

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

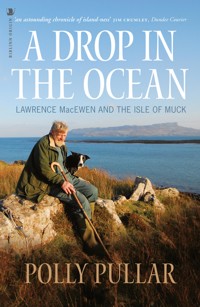

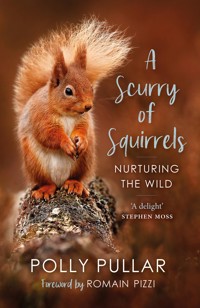

Polly Pullar is a field naturalist, wildlife rehabilitator and photographer. She is also an acclaimed wildlife writer and contributes to a wide range of publications, including BBC Wildlife, the Scots Magazine, Scottish Field and Scottish Wildlife. Her previous books include A Richness of Martens – Wildlife Tales from the Highlands and A Scurry of Squirrels – Nurturing the Wild. She lives on a small farm in Highland Perthshire surrounded by an extensive menagerie. Follow her on Twitter: @pollypullar1.

The Horizontal Oak

A Life in Nature

Polly Pullar

First published in 2022 by

Birlinn Ltd

West Newington House

10 Newington Road

Edinburgh EH9 1QS

www.birlinn.co.uk

Copyright © Polly Pullar 2022

ISBN 978 1 78027 780 6

This book is a work of non-fiction, however some names and identifying details have been changed to protect the privacy of the people involved.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored, or transmitted in any form, or by any means, electronic, mechanical or photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the express written permission of the publisher.

The right of Polly Pullar to be identified as Author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form or by any means without permission from the publisher.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Typeset by Initial Typesetting Services, Edinburgh

Printed and bound by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A.

For FreddyWith all my love

Contents

Introduction

1 A Childhood Eden

2 West of the Sun

3 The Spell is Broken

4Vive la France!

5 Exmoor

6 Skeletons out of the Cupboard

7 Monkey Business

8 A Bitch of a Month

9 Fishwifery

10 Gutted

11 Freddy

12 Snowy Owl

13 Not Good Enough

14 A Fawn, Two Collies and the Flight of the Condom

15 Making an Ass of Myself

16 More Misunderstandings

17 Geordie

18 Mongol Rally

19 Chasing Light

20 Hospital

21 Frogs

22 The Horizontal Oak

Epilogue

Introduction

There’s a single oak high on the flank of Ben Hiant, overlooking the Sound of Mull. I have known this resilient tree since my early childhood. It’s in a place I love very much. Massaged by the warmth of the Gulf Stream, battered by the wrath of the Atlantic and silhouetted by a thousand sunsets over the islands of Mull, Coll and Tiree, it is horizontal, its trunk fissured and colonised by tiny ferns. An oak sustains more life forms than any other native tree. Generally, we think of oaks as mighty: trees for building houses, boats or bastions; trees of grandiose parklands, their massive weighty boughs stretching to the heavens. The oaks of Scotland’s rainforest on the western seaboard are different: diminutive, wind-sculpted. Many do not stay the course while others, like mine, grow strong and beautiful as they find succour between a rock and a hard place. Raven, hooded crow, buzzard and tawny owl frequently visit this tree. Sometimes it will be the little stonechat with his dapper black bonnet. And, from time to time, it is me, for its trunk, having withstood so much abuse, offers me support too; the horizontal oak, high on a hillside west of the sun.

*

Ordinary families like mine hide secrets, issues and struggles that cause pain. When my mother died, I knew that it was time to come to terms with the strains of my relationship with my parents. For far too many years this consumed me, spiralling out of control and leading to tragedy. I usually write about nature and have found writing about personal issues troubling, yet this journey has been burning deep in my heart for a long time.

In nature – in wild places, and through some extraordinary close relationships with animals and birds, both wild and domestic – I have found the peace that nurtures my soul. In particular, I have returned again and again to Ardnamurchan, a remote, mercurial peninsula flung west towards the setting sun, where nature embraces me in its many moods. And to that oak tree; it’s as fine a place as I know for reflection. And calm.

Few are lucky enough to avoid life’s emotional battles, but it is how we survive them that matters. Do we cling on and become more weathered and lined, like my horizontal oak, or do we instead blow over with the first hard gust of wind? Perhaps this nagging at our roots strengthens us, and maybe even leads us to a better understanding of the problems we all face.

My life and work are woven around nature. The natural world forms a vital part of this memoir and provides a continual counter-balance of hope. Hope and a sense of humour are essential emotional ingredients for life. Laughter helps us find ways to continue when things are testing. Here, then, is a little part of that story.

1

A Childhood Eden

‘Polly, you are so lucky to have owls in your ovaries.’ I was peering through the kitchen window watching tawny owlets in the aviary in the garden with a friend’s eight-year-old daughter. Children do not realise the power and wisdom of their priceless statements. It was appropriate because wildlife has always been part of my very being, though perhaps not my ovaries. She was right; I consider myself fortunate to work closely with injured and orphaned wild animals and birds. As well as making me laugh, her statement brought forward a vivid memory from the annals of my mind, from Cheshire, around 1966: that morning when I discovered my first tawny owl.

The garden was an amphitheatre of birdsong. It drifted through my open bedroom window. Jackdaws were ferrying twigs to the collapsing chimney in the old stables next to the house. One of them had long wisps of sheep’s wool in its bill – it looked like a Chinese wise man with a drooping white moustache. I listened to their effusive chatter, so many different calls, some almost human. The fireplace in the wood-panelled tack room bulged with sticks and twigs spewing forth onto the cracked stone floor. Sometimes I collected them for Mum to use as kindling. They were surplus to the jackdaws’ requirements for they only used the ones at the top to create their shambling nurseries. In a continuous stream, more and more sticks were flown in, and the chimney echoed to the sound of their chortling, chakking communications with their voracious youngsters.

A dead jackdaw lay rotting in a verdant grave of emerging nettles close by. It had died a week earlier, but I didn’t know why. I’d found it when it was still warm, its smoky hood and glossed indigo-black plumage fresh, its eyes topaz blue. There was not even a speck of blood to reveal a fight with one of its kind; perhaps it had had a disease. I’d wished I could have saved it. I raced outside for another quick look before school. That day the bird’s eyes were sunken, the blue faded to storm-cloud grey, and its feet clenched in a death grip, claws earthy under sharp nails. I turned it over with my foot, watching iridescent beetles and creamy maggots working on its decaying flesh. The smell was overpowering, but the bird was moving in an intriguing way. Beside the gruesome scene, there was a splash of brilliance: celandines and dandelions were opening their bright faces. The bird had flowers on its grave.

I heard a soft churring sound, almost inaudible, merely a whisper. It was close. I had never heard it before. I looked up and saw an owl perched in the open hayloft doorway above me, its burnished bronze plumage dappled with light rays that briefly illuminated festoons of lacy cobwebs around the corners of the opening. It was the most beautiful bird I had ever seen. It drew itself up tall as if to make itself invisible, narrowing its huge dark eyes to mere slits, and then it swayed its body over to lean up against the sandstone. I stood motionless, captivated.

Mum shouted, ‘Pol, time to go.’

I pretended not to hear.

Then after a few minutes, she shouted again, ‘Pol, will you please hurry up?’

I stood still, frozen to the spot, watching. It was so similar to Old Brown, the tawny owl that snatched Squirrel Nutkin’s tail in the Beatrix Potter story Dad’s younger brother, Uncle Archie, had read to me. Mum yelled again and gave one of her trademark whistles. This time she sounded cross. I ran round to meet her, stumbled over a heap of slates and cut my knee on a sharp edge. There was no time to fuss, but the blood oozed stickily into my sock and made me wince. Mum was revving the car engine; I grabbed my satchel from the path where I had dropped it and leapt in the back as we hastily departed for school.

I hated school, and Mum understood because she had hated it too. On the way, I told her about my discovery. ‘I can’t wait to show you when I get home. It’s such a big owl and it’s just sitting and staring. Do you think it lives there? Will it be there when I get home? Please, can we go back now and have a look? I have a bit of a tummyache, perhaps I should stay at home today.’

The day dragged longer than usual. I was lost in reverie. Such a beautiful, perfect owl! Every O or 0 on the blackboard reminded me of those big, darkly round eyes.

‘Polly, will you please pay attention, what are you doing, you have not been listening to anything I have been saying, have you?’ snapped the teacher, rapping the blackboard with her knuckles and tutting loudly.

I didn’t like her; she was always irritable. The owl consumed me, and I wished it were time to go home. I wanted to venture up into the loft to see if I could get even closer, but the wooden stairs were collapsing and the slates were tumbling off the imploding roof. I wasn’t supposed to go up there.

As soon as I was home, I gulped tea in a hurry and ran across the yard to the cottage close by, where my friend Alan was waiting. He didn’t go to a boring all-girls school like me, and he arrived home earlier. Most days we raced out to play together.

‘There’s this gi-normous owl, we have to go and see it,’ I told him.

Alan’s eyes opened wide. He still had his grey uniform shorts on, had matching cuts on his knees, and a permanently dirty nose.

‘Don’t be late for your tea again!’ shouted his old grandma from her knitting perch by the fire. Alan shoved his wellies on the wrong feet and left the house coatless, without shutting the door.

‘Dad says she’s a silly old bat,’ said Alan, who ignored all instructions that didn’t suit him.

We crawled around the corner of the stables on our hands and knees so as not to frighten the bird away. Miraculously it was still there – this was its chosen daytime roost.

From then on, every day after school we looked for it and sometimes saw it flitting silently through the trees. I became so absorbed by our woodland explorations that I never noticed how stung and scratched I was until I stepped into the bath at night, and then my stings and cuts made me yelp. We learnt that the blackbirds and other songsters gave the game away, scolding and revealing the whereabouts of owls or other birds of prey roosting deep in the surrounding woodland. We carefully followed their irate protestations and were usually rewarded. Then we discovered a heap of owl pellets beneath the hayloft window and began a forensic investigation of their contents. Alan borrowed a magnifying glass from his grandma, and Mum gave me an old pair of tweezers. Within the woolly grey casing, we revealed perfect little vole and mice skulls bleached white, tiny feathers and minute skeletons, as well as beetle cases. We also tracked deer, rabbits and hares, following their prints through muddy pathways where tripwires of brambles waited to snag bare legs. I grew increasingly feral as my desire for wildness blossomed.

My parents never minded that I was outside all day and only appeared for meals. I often missed those too. Mum, remembering her own free-spirited and outdoor childhood, could clearly relate to mine, whilst Dad worked long hours in his office in Liverpool, only returning when I was ready for bed. Dad loved nature too.

When the window was empty, the owl gone, we tiptoed up to the hayloft, barely putting our weight on steps like seesaws. Upstairs, it was stifling with the smell of rats; there were layers of dry grain husks and mould-covered droppings, fusty empty hessian sacks latticed with cobwebs and massive spiders emerging threateningly from every corner.

‘There are probably vampire bats up here. It’s the perfect spot for them,’ Alan informed me as he led the way. He seemed brave and knowledgeable.

The gaps in the floorboards were wide as crevasses, and shafts of light revealed even more cobwebs, with struggling bluebottles fizzing out their last before succumbing to the spiders’ efficient strangling shrouds. And then there were even bigger spiders. Startled pigeons clattered from the rafters as we leapt back and teetered on the edge of a gaping floor crack.

Bones lay in a heap by an upturned metal bucket plastered with white droppings. ‘Do you think they belong to a dead person?’ I asked Alan.

He laughed dismissively and replied, ‘I bet they do.’

That attic made me feel uneasy and itchy, all the dust and rancid hay left in piles. It caught the back of my throat and scared me.

‘My grandma says a tramp sometimes sleeps up here. She says he is an escaped convick,’ Alan announced.

‘What’s a convick?’ I asked.

But he didn’t know either and shrugged. Even though I was frightened, the prospect of getting a little closer to my owl made it worth the terror. Little did I know then that owls, in particular the tawny, were birds that would continue to feature intermittently throughout my life, birds that I would come to know, love and understand quite well.

The only time we were not outside was when we watched the television series Animal Magic and Daktari. Presenter Johnny Morris of Animal Magic was our hero, and on the programme he was often a zookeeper projecting imagined voices of the various animals he cared for. His conversations with them were hilarious. I was intrigued by the chats he had with a huge gorilla. For me, a ring-tailed lemur called Dotty was the main attraction; she was always keen to take another grape from her keeper. It made Alan and me giggle when she politely took one from his extended hand. I longed to have a ring-tailed lemur too. Due to Animal Magic, I quickly learnt to recognise many exotic animals and birds, and on wet days lost myself in books with photographs of wonderful creatures.

Daktari is Swahili for ‘the doctor’; that programme was set in Africa and centred on Dr Tracy and his daughter Paula, who protected animals from poachers and rescued various ailing birds and beasts. They had an animal orphanage. As I wanted to be a vet, Alan and I acted out dramatic animal rescues. He was the dashing Dr Tracy, and I was Paula, whilst Penny, our yellow Labrador, was their famous pet, Clarence the cross-eyed lion.

When I was alone, Penny also sometimes became Yellow Dog Dingo from Rudyard Kipling’s Just So Stories, another favourite of the books that Uncle Archie read to me. She was very obliging and, being a greedy dog, was happy to go along with anything providing there was a titbit involved. When she came with me through the woods on my expeditions and I found dead things, she’d let the side down by rolling in them and then we’d both get a row when we got home. I had a large toy monkey that we used for Judy, Daktari’s chatty chimpanzee. We had pots of red poster paint for the blood transfusions that we carried out on our imaginary patients, and bamboo canes stuck onto toy building blocks as our walkie-talkies; we ran around the woods and garden frantically searching for ailing wildlife. We sometimes found needy fledglings, once or twice a road-casualty hedgehog, and tried to save them. Mum helped too, and was especially good with the hedgehogs.

Once, we found an abandoned pigeon squab that looked like a dodo. ‘Pigeons are difficult baby birds to rear,’ said Mum, ‘because the babies need special milk made in their mothers’ crops and they feed by putting their funny little bills straight into their mothers’ throats.’

There were other excursions, such as when Alan and I sneaked over a tall iron-spiked fence at the manor house close by, and into an ancient orchard to steal apples belonging to Lord Leverhulme. Once, we were almost caught and a woman yelled at us as we fled in a panic. We were in such a hurry to get back over the wicked pronged fence that my bright-blue knickers snagged and ripped right off, and I had to race home without them. They were still hanging there next morning like a little tattered flag, but I dared not go and retrieve them.

*

When I was in my teens, and long after my parents had parted company, my mother laughingly told me that during the early years of their marriage, she and my father were nicknamed ‘the two PBs’ – the pompous bugger and the promiscuous bitch. It’s not the greatest accolade applied to a couple, is it? As far as I can understand, and from numerous photographs and anecdotes relating to those early years, they were in fact incredibly popular. They were a flamboyant pair who loved parties, and were both renowned for their wit and devilish sense of humour. Mum made an impression wherever she went – she was sexy, flirtatious and colourful, she dressed with style, and men found her irresistible with her red hair and exuberant twinkle. She had a gap between her front teeth through which she could whistle so loudly and efficiently that it could make even the most disobedient fleeing dog skid to an immediate halt. It had a similar effect on people too. Particularly men. Mum was effervescent, and game for anything. When I was a small child, she was always kind. She let me spend most of my time outside, as she had done during her own childhood. And this suited me just fine.

Men said that Mum looked just as sexy in her old gardening clothes as she did when dressed for a special occasion. She was athletic, loved swimming and tennis, and had learnt to ride bareback with the local gypsies on a carthorse called Blossom, whose back was so broad you could have played patience on it. In many aspects Mum was fearless, but she hated flying and boats, and was a dreadful back-seat driver.

My grandmother told me that Mum was a very naughty child. One of her early school reports read: ‘Anne is a born leader, it’s just a pity that she leads in the wrong direction.’ That particular comment came after she had taken her school friends out onto the roof through an attic window and waved at the headmistress, who was standing below in a state of anxious rage.

Mum was passionate about animals. When I was very young, we visited the exotic Harrods pet shop, in Knightsbridge, where we almost succumbed to the charms of an armadillo. The poor thing was utterly miserable and dejected in a wire cage. I was desperate for Mum to buy it, but it came with a hefty price tag. For the rest of her life, we frequently spoke of that little creature that had been stolen from a remote part of wild South America, only to be brought back to this country to be put up for sale in a fashionable London emporium. We always wondered what happened to it.

‘I longed to buy it,’ Mum said, ‘not only because it was gorgeous but also so we could look after it and give it a nice home. But it really was way out of our budget. I have regretted it ever since and get miserable even thinking about it.’

Both my parents were involved in raising money for the World Wildlife Fund. I remember how aware they were even during the 1960s of the parlous state of the natural world. They would be deeply concerned, saddened and shocked if they knew how serious the situation has since become.

Mum adored my father, though she was advised not to marry him as his family had a history of alcoholism. Mum went ahead anyway. She had the stubbornness and determination of a jaded donkey that has worked a tourist beach all its life and is sick of demands made by horrid little children. If she disagreed with something, she wouldn’t budge; like a donkey, she would dig her toes in. Indeed, she probably was promiscuous. Reflecting back on it all now that both my parents are long gone, I think she had good reason.

Dad – ‘the pompous bugger’ – had delusions of grandeur. If he had been a duke or an earl, he would have been happy. He loved double-barrelled names, as well as titles. Mum always joked about it. In 1950 he changed the family name by deed poll so that he and his brother, Archie, became ‘Munro-Clark’ instead of just plain ‘Munro’. Clark was part of their mother’s name. It was an odd thing to do. He was always adamant that people employ his full appellation. He was indeed pompous at times, sometimes so much so that it made me cringe.

But Dad was also exceedingly charming and had impeccable manners. His wit and humour were equally as sharp as Mum’s, and he loved practical joking – he had caught out all his close friends with his innovative trickery. These jokes were always humorously entertaining and never designed to hurt. Some were complex and involved considerable planning. Many were played out over the telephone. He loved the phone and used to infuriate my mother by ringing someone shortly before a meal, and then spending hours engaged in conversation. Dinner went cold.

Dad loved tweed – Harris tweed especially. He loved perfectly crisp shirts from London’s smart Savile Row. He loved cufflinks, and endless changes of socks – the latter because he had sweaty feet and athlete’s foot. Our bathmats seemed ever to be liberally sprinkled with a snowy dusting of foot potions. Even though they had little money, he insisted on having his best clothes made by ‘his tailor’, as he grandly put it. He dressed immaculately, and in the perfect garb for whatever he happened to be doing at any given moment – even digging the garden – though he usually tried to extricate himself from that.

Dad was highly skilled in the art of manipulation and avoidance and could make an excuse to get out of anything he didn’t like doing. He had avoided National Service because he said he had ‘flat feet’, and then of course there was the athlete’s foot. He hated moving furniture and evaded any suggestion that he might lend someone a hand to move, say, a bed, or a sofa, and instead instantly made reference to his bad back. He would then go in search of a copy of Yellow Pages to find a firm of furniture removers. However, he could out-walk almost anyone, particularly if it involved hills and mountains, flat feet and bad back long forgotten. He loved shooting and deer stalking, but at school, though bright and academic, Dad had never been any good at ball games. He was a serious bookworm and read avidly. All the time. He also always knelt at the foot of the bed every night and put his hands together to say silent prayers. I found this fascinating.

Dad loved gourmet food, and he loved bitter black chocolate, strong tea, and even stronger coffee. Sometimes it seemed like liquid toffee. It was usually lavishly sprinkled with saccharine instead of sugar. ‘If I had sugar too, I would be even fatter.’ He loved to eat double cream straight from the pot. ‘I cannot resist it,’ he would say, dipping a teaspoon straight into a carton laced liberally with soft brown sugar. Thick yellow Devonshire clotted cream made him childlike.

Both my parents spent a lifetime battling with weight issues. I grew up thinking that saccharine actually kept you slim. I even tried eating it straight from the container. It was disgusting. Dad frequently won his weight battles and went through trim phases. Relapse, however, was guaranteed. He had a highly addictive personality.

Mum, conversely, totally lost control of her increasing buoyancy. She always blamed me: ‘It’s your fault entirely, I was quite thin until I got pregnant, and piled it all on then.’

Early photographs prove that this was not entirely accurate. Mum was never a sylph – she was simply not made that way. Dad also loved fine port, French wine, champagne, whisky, gin and brandy, indeed anything alcoholic. Unfortunately. Dad loved it far too much.

The two PBs – Anne and David Munro-Clark – rented part of a rambling house from Lord Leverhulme on the Wirral peninsula. It was a beautiful sandstone pile riddled with damp and dry rot and surrounded by a wild, rampaging garden; a maze of azaleas and rhododendrons formed dark, exciting tunnels for dens and exploration, and in spring a green slimy pond overflowed with frogs and toads. The house had a leaky conservatory that housed flowers and peaches. In the other half of the house lived a wonderful eccentric family who became my parents’ long-standing close friends. Their daughter, Heather, was made my godmother when she was only eleven years old. This was an act of genius on the part of my parents as she has always been the greatest support throughout my life.

Builders were tackling the dry rot while we lived there and, typically, left their scaffold and shambles up the sweeping staircase whilst vanishing off to do other jobs. One of them had scrawled, ‘THE POPE FOR PRIME MINISTER’ on the crumbling plaster. Venturing up and down was a hazardous obstacle course. Early one Sunday morning, I found Dad suspended over one of the lower rails of the scaffold like a battered scarecrow, in a semi-rigor state, with a shoeless foot in a bucket of hardened cement and fag ends. He was snoring loudly and dribbling whilst repeating, ‘Poor show, poor show,’ over and over again. He didn’t resemble the Dad I knew. I felt scared and beetled back to bed.

Years later Mum told me that she had given up trying to manoeuvre him in his inebriated state and had said, ‘Fuck it’, and just left him to get on with it.

Dad was exceedingly well read. He went to Cambridge, and though my mother was no academic and never passed any exams, it was there that they met one another and fell in love. She had been invited for a weekend and had tagged along to yet another drunken soirée where Dad was apparently both intoxicating and intoxicated. She soon became part of his Cambridge set.

Now they are both gone, and I can no longer ask them what happened next, I have to imagine so much of their story, and there is a gap I am unclear about. However, later, Dad, having studied law, decided not to take it any further because he unexpectedly inherited a timber business in Liverpool from an elderly uncle. Part of their business was supplying coffin oak, and on one occasion a Jewish undertaker took him into the back of his premises to show him a beautiful young woman perfectly made up and lying in her coffin. This really upset Dad, who realised that he was in totally the wrong profession. He didn’t like it anyway. With the business, he also inherited two elderly gentlemen who worked in the office, filling ledgers in with ink quills in perfect copperplate writing. They became victims of one of his many practical jokes, on this occasion, more cruel than usual. He put stink bombs in their room so that each blamed the other for having rotten guts.

*

Our lives were filled with animals. We had another gluttonous golden Labrador, Jane, who was Penny’s mother, and later two spaniels and numerous other dogs, and a ginger Persian cat called Oswald Bull – named after Miss Bull, his eccentric breeder. He got knots in his fur and suffered from incontinence. He piddled on my parents’ eiderdown so that the red dye ran onto the sheets, leaving a pink, immovable stain. ‘That’s Ossie’s piddle patch,’ Mum announced each time she hung the sheets on the line.

Mum, who had always been fascinated with parrots (perhaps that’s why I am called Polly), had an African grey with a nasty cough for which, despite extensive, expensive veterinary investigations, no reason could be found. We later discovered that the parrot’s previous owner had been a chain smoker and coughed uncontrollably every morning.

Jane and Penny were dreadful scavengers and often bumbled off on their own little expeditions. For some weeks they came home stinking appallingly and had to be bathed. Eventually, the source of the vile stench was unveiled. A policeman called in to see my parents and told them that a dead tramp had been found in a nearby ditch and wanted to know if they had ever seen him before. This caused much upset. The dogs were in disgrace – they had found him first. The golden duo also regularly raided Lord and Lady Leverhulme’s bins, something my parents found embarrassing.

‘Ah! Theirs must be a far better class of rubbish,’ Dad commented grandly. He liked living in close proximity to a lord. His middle-class family were never wealthy, but it didn’t stop his aspirations.

I had a square chestnut Shetland pony called Peggy that I had been given for my sixth birthday. Peggy was over thirty and knew all about children and how best to handle them, having done the rounds locally. She was a besom. She dented my confidence and regularly bucked me off into the nettles, or placed her sharp little hoof deliberately over my foot, leaving it raw and bruised. She was an awful biter too, but such Thelwellian ponies were part of a character-building package that for a tomboy like me included copious amounts of tree-climbing, den-building and nature absorption.

Dad’s brother Archie, who was a schoolmaster, had a flat in part of our rented house. I became hopelessly overexcited when I saw his little car coming up the drive returning for his school holidays. He loved children and always brought wonderful books to read to me. He gave me the complete set of Hugh Lofting’s Dr Doolittle. I used to dream of being able to talk to animals as the doctor did. These stories unfolded a vast world full of fauna that formed a mantra for my life.

Archie was more down-to-earth than Dad, and far less conscious of his appearance. Whilst Dad loved looking smart and dapper, Archie was more casual, though having spent two years in the Royal Navy he could be just as immaculately turned out when the need arose. He was the seventh generation of the family to go to sea and though he almost stayed on, he decided instead to pursue an academic career; after graduating from Cambridge he took a post at a boys’ prep school in the south of England. This became his lifelong career. He was a supreme communicator with people of all ages. Well-read, like Dad, he taught English, History and Games, and also wrote and produced the school plays.

Being a schoolmaster meant fantastic long holidays, and paid accommodation in term time. When he came back to stay with us, Archie and Dad sometimes smoked fat cigars together and sat up long into the night talking. In the morning the tarry aroma lingered amid the unwashed whisky glasses on the kitchen draining board.

Archie was always laughing. He’d laugh on long after a joke had passed. The sound reverberated around a room so that even if you didn’t understand the reason for all the hilarity, it was infectious. He was always laughing at himself too. I liked that.

Mum, Dad and Archie were very close and clearly enjoyed doing things together. I remember now that they were together for much of the school holidays. Though Dad also read to me, he was often absent, and Archie filled the gap. At the time I never questioned this. It was simply the way it was. Perhaps Dad was working late.

My finest early childhood memories are those of Mum’s mother, my grandmother, Bo. She was a treasure. A plain-speaking Yorkshirewoman, she was the kindest person I have ever met. There was nothing complicated about Bo; she was perfectly at one with herself and everyone else, and she too had a fabulous sense of humour. She and I shared the same birthday, and were as close as identical twins. She frequently fetched me from school, and I stayed with her in her lovely low, white cottage in the village of Heswall in Cheshire. The walls were thick and uneven, the stairs creaked, and there was a damp stain spreading over the bathroom wall that looked like a map of Africa. She would put an electric wall heater on whilst she ran my bath, and the room would fill with a dense blanket of steam. ‘Is there anyone in here?’ she’d laugh as she came in to check. The steam made the paint peel.

Bo had a blue budgerigar, Charlie, who was very talkative. ‘Why do you buy such small packets of birdseed for him?’ my grandfather asked her. ‘It’s so much cheaper to buy large ones.’

Without a moment’s hesitation she replied, ‘He is so old I am worried that if I buy a big packet, it may tempt fate and he will die, so I daren’t.’ She was a very generous person, but Charlie meant a great deal to her.

My grandfather’s name was Wilfred – Wilf – but he had always been nicknamed Fitte. ‘Fitte’s bloody awkward,’ Mum would say.

I never saw that side of him. Their relationship had always been volatile. When she was a child her strong will drove her father to distraction and, as it had become even stronger over the years, they did indeed seem to have a problem getting on with one another. There were frequent clashes. I once overheard Mum saying – ‘My father prefers Polly to me.’ She sounded hurt.

Fitte’s mother was said to have been erratic, with a lashing tongue that was reputed to cut you in half. She was from a large Irish family in County Tipperary, and her grandparents were tinkers. I loved it when Fitte told me stories about them after he’d had a few glasses of sherry in the evenings. They sounded dramatic, colourful, wild, unruly, and so exciting. When I thought back on this years later, I often found myself hoping that I might have inherited some of their genes, rather than a collection of alcoholic ones from the other side of the family, for both Dad’s parents had serious drink problems. This sad fact was frequently rattled out as part of the conversation.

‘You come from a line of bloody drinkers,’ Mum would say.

It didn’t sound a great prospect, though at the time I didn’t understand what it really meant.

Fitte was a quiet, shy man with a sense of humour so dry it would have served as kindling. Like Bo, he was very generous. He had been a market gardener and still kept a beautiful garden lush with vegetables and bordered by dozens of cheerful polyanthus. The sweet little tomatoes from his greenhouse picked straight from the plant, tasting of sunshine, were something we relished.

Bo once said the only religion that mattered was being kind. She also told me that you should always tell people what you think of them with regard to love, and treat them as if today might be the last day you saw them. Once, when she was very old, there was a knock at the door and a man pushed his way forward, saying, ‘I have come to tell you that Jesus has risen from the dead!’

Without hesitation, Bo replied, ‘Right, I had better go and put the kettle on straight away.’ And then she politely shut the door.

Bo was fun and, like Archie, she was always laughing. She had slim legs and a big bosom, and she wore corsets and stockings, something I found intriguing as she hooked herself into an odd rigid garment that she said helped hold her tummy in. She was a huggable person, overflowing with warmth; everything felt right when I was with her.

We used to go straight to the local bakers from school and collect iced buns, or chocolate eclairs for tea. One day whilst we were waiting to pay, I asked, ‘Was your grandmother an Ancient Briton?’ as we were studying them at school.

Everyone in the shop laughed. ‘I’m not that old,’ I heard her tell them.

Bo was a skilled bridge player, and was closely involved in the local club where she was in great demand as a partner. She often had bridge afternoons with sumptuous afternoon teas, and then ‘a spot of sherry’, or a glass or two of Gin and French. Those tea parties lasted well on into the evenings. She was an integral part of village life, and everyone adored her.

Both my grandparents were heavy smokers. Mum laughingly told them, ‘You two will puff yourselves to death if you don’t stop.’ However, they had a goal to acquire more cigarette coupons so they could obtain toys and games for me, and garden tools out of the cigarette company’s catalogue; they must have had a marathon smoke in order to secure enough coupons for a wonderful shiny bike with stabilisers, but they did it.

My grandparents loved the birds in their garden. We would watch them bathing in a stone birdbath, or feasting on all the things Bo put out for them. We loved the starlings best because they were cheeky, and their antics and mimicry made us laugh. One in particular could perfectly imitate a curlew, whilst another was a buzzard impersonator, and several had perfected the cries of herring gulls. Then there was one champion that could whistle like Bo’s cheeky milkman. She referred to them as the ‘star-spangled starlings’ due to their iridescent rainbow plumage. When the sun shone on them, I thought their colours resembled oil spilt on a puddle: purples, mauves, blues and yellows – pure perfection! Fitte had a passion for the robins that followed him around when he was digging. He always kept a few titbits in his shirt pocket.

The best thing about grandparents is that good ones have time. Both Bo and Fitte listened to all my chatter. They believed in me and were always encouraging. At times children need to be taken seriously. Ours was a relationship like no other. My grandparents were earthy country people, and everyone respected them both.

2

West of the Sun

During the 1960s, my parents found Cheshire’s increasing urbanisation a threat. Dad hated the timber business and was trying to sell it. They had reached a point where they wanted to have a complete change. Though the Wirral peninsula was beautiful, the roads were becoming busier every day and the landscape scarred by sprawling development.

As our house was only rented for a nominal rate, my parents had bought a tumbledown cottage called Ogof in the mountains in North Wales. It was in an isolated situation near a remote, unmechanised hill farm. Sometimes we went to the farm to help the Jones family – two brothers and their wives and children. At milking time, in the afternoon, we would often help them bring in the cows, and in summer extra hands were always much appreciated to help with hay making. I remember the steaming cowshed where they kept half a dozen cows. Their hot, sweet breath hung in thin clouds that danced slowly upwards, among sparkling dust specks and weak sun-light that poured through the small window.

‘Taste this,’ said one of the brothers, passing me a small enamel mug of milk that he had dunked into a metal bucket as he rhythmically milked their house cow. It was frothy and creamy. Everyone laughed because I had a milk moustache on my top lip.

I was playing in the garden with the dogs when I encountered my first adder. A passing buzzard had perhaps dropped it. When I saw it, I assumed that our dogs had pinched a very similar-sized rubber snake I had that we frequently used as a prop in our Daktari safari adventures. I went to reclaim it. Then it wriggled and swiftly moved towards the old wall that surrounded the garden. Mum shouted urgently from the window and told me to leave it alone. She rushed out waving a tea towel. She seemed worried. There was urgency in her raised voice.

Once the adder had vanished, she explained that this was Britain’s only poisonous snake, and I must never touch one again. ‘They are lovely, beautiful reptiles but you really don’t want to be bitten. Sometimes dogs die of adder bites, Pol, so please do take care and if you see one again, you promise me you will leave it alone, won’t you?’

When Mum told me to leave something alone, I never questioned her. She had always taught me to look into birds’ nests and take note of their beautiful eggs, but never to touch them or take any. Mum knew about nature and how important it was to have respect for it. Like the tawny owl, the adder fascinated me. Grey, black and terracotta markings patterned its body, and its head had distinctive Vs on it. I found some adder pictures in one of my books. I wished there had been an opportunity to look at it really closely. Perhaps most surprisingly, it hadn’t looked slimy. So why did people always refer to snakes in this way?

In 1966, when I was six years old, we were to spend Christmas at Ogof, and in the lead-up whilst visiting Father Christmas in a soulless department store in Liverpool, I became terribly anxious in case he might not know where I was going to be. The shop was hot and stuffy, frantic with shoppers, as we made our way to the grotto, a tented den at the back of the toy department with a sad-looking plush reindeer standing at the entrance. Its eyes were too big. I knew reindeer did not have lashes that long as I had seen them in my books. I was also sure their noses weren’t red. This one had half of a red ping-pong ball stuck onto the end of its snout.

Inside the grotto Father Christmas sat bursting forth from his crimson suit. I sat on his capacious knee and explained my worrying predicament. ‘You see,’ I said, ‘I’m not going to be at home this Christmas and I want to make sure you know where to come. You don’t even have my address do you?’

He listened intently as part of his beard began to peel away from his fat, round flushed face.

‘We are going to be in Wales, and this is the address: Ogof Llechwyenn, Penrhyndeudraeth, Gwynedd, Merionethshire, North Wales.’ I slowly spelled it all out for him to make sure he was left in no doubt.

He looked at me curiously, every stitch of his red outfit doing its duty and his white beard now quite adrift. Then he exclaimed in broad Liverpudlian, ‘Flippin’ ’eck, chook, thare’s a mouthful!’

Ogof was a beautiful place nestled deep in mountainous landscape. The surrounding hills were the domain of buzzard and wild goat. Sometimes I could smell the goats. The billies had a ripe, sickly smell that I didn’t like. We occasionally saw choughs, crimson legs and bills cherry bright against a cloudless sky, their teasing, chuckling calls echoing over the valley. High above the cottage, hidden in the hills, there were eerie caves with dripping ferns fringing dark entrances that gaped like the toothless mouths of old men. Sometimes we would walk up and shine a torch inside, but Mum and Dad never let me go in. The area was latticed with old slate workings, and many of them were collapsing. Dogs had been lost, and once a boy had gone missing too. He was never found.

One morning some gamekeepers with aggressive, scarred, rough-haired terriers passed the cottage. They had been out looking for foxes and had a very young injured badger cub in a bloodstained game bag. My mother was talking to them over the garden gate, and by the time the conversation was over she had persuaded them to part with the tiny cub. This was my first experience of hand-rearing a wild mammal. We took it home with us when we left Ogof after the weekend. Sadly, though Mum did her best, keeping the cub warm on hot water bottles, and feeding it every few hours with puppy milk from one of my doll’s bottles, it skirted precariously on the edge of life for a week, and then died suddenly. Mum said that the dogs had probably caused irreparable internal damage, and told me that it had succumbed to peritonitis, and severe stress brought on by separation from its mother and the other cubs. By the time I was having breakfast, Mum had already been out into the garden and buried it. When she told me, I was beside myself with a sadness I had never before experienced. It burnt deep inside and made butterflies race in my stomach, and with them also came fear – a fear that was new to me. I cried so much I had to miss school. However, I quickly learnt that if you love animals you must also learn to accept the devastation of their departures. That first close proximity to death lingered long.

Most years, Mum and Dad had holidays in Scotland and went deer stalking every autumn. They had always wanted to move north and return to their roots. By the time I was nearly seven, they were planning to leave Cheshire and to sell Ogof; they were looking for an alternative lifestyle. Dad no longer wanted to commute back and forth to Liverpool, and in a flash of inspiration they thought of running a hotel together instead.

We went to view two West Highland hotels, travelling by sleeper with the car from Crewe to Inverness. This was a service called Motorail that ran for a short time for long-distance travellers. Watching Dad drive onto the train’s special deck added excitement to the trip. I loved the sleeping compartment that I shared with Mum, with its crisp white sheets and delicious little packets of biscuits brought with the morning tea by the steward at some ungodly hour.

‘Make sure you aim straight, Pol,’ giggled Mum after she had squatted over the porcelain potty full of piddle and then posted it back into its cupboard, delivering its contents onto the railway line.

Going on the sleeper was an adventure as it rocketed along rhythmically covering the miles. ‘I’m not going to sleep, I want to watch the lights as we flash past,’ I announced, peering under the window blind. But I was soon overcome with tiredness.

At Inverness we drove on north, heading through a world of wild, sweeping grandeur, where vast sprawling lochs fringed by russet and gold reeds and bogs perfectly mirrored the mountain drama. When I saw Stac Pollaidh (pronounced Polly) for the first time, on our way to Achiltibuie, it filled me with excitement, for not only did it have my name, it looked like a giant’s castle straight out of a Grimm fairy tale, its grey grizzled battlements and turrets honed from sheer rock. Its craggy, giddying top wisped with low cloud like smoke coming from a secret hidden chimney on its castellated bastion. Just a couple of years later whilst on a fishing holiday, Uncle Archie took me to the summit. Stac Pollaidh was one of the first mountains I ever climbed, and I have been joyously climbing mountains ever since.

At the Summer Isles Hotel, the owner proudly showed us around, with great emphasis put upon the importance of fine fare despite the remoteness of the location. We were taken into the larder and shown an enormous cheese bell.

‘This is where we always have a perfectly ripe vintage Stilton, a vital part of any good menu,’ he announced, lifting off the lid.

‘So important to accompany a glass of exquisite vintage port,’ said Dad, smacking his lips and putting on an exaggerated grandiose tone. Dad was passionate about strong cheese, and quite a connoisseur.

Atop the reeking cheese, a small, immaculate brown mouse sat cleaning its whiskers. The lid was firmly put down again as our host glossed over this minor cartoon-scenario setback. We laughed about it for days.

However, instead of the Summer Isles, my parents chose the Kilchoan Hotel, in Ardnamurchan, on the Sound of Mull. The mouse nearly swayed their decision.

We were embarking on an adventure, and I was filled with excitement, but worried that I’d miss Bo and Fitte who were staying on in Cheshire. On the other hand, I had seen so many pictures of red deer, wildcats and eagles in my books that the thought of perhaps being able to see them for real filled me with glee. And I hated my dull school and hoped that perhaps my new one might be better. And then to live really close to the sea might mean I could see whales and dolphins.

Moving house is chaotic. Months of planning and packing result in eternal cardboard boxes and piles of miscellaneous belongings that fail somehow to warrant a place in the bin, the local charity shop or the new abode. When a move involves a complete change of occupation, a totally different lifestyle, and a far-flung location, bravery also plays a part. My parents were fortunate that the timber business sold quickly, and someone had also bought Ogof. Whilst they packed up and made interminable plans, I spent time with Bo.

Our departure from Cheshire in November of 1967 in a long-wheelbase Land Rover crammed with luggage, dogs, a parrot and a cat, was fraught. On the eve of our departure, there was a deafening thunderstorm that terrified me and made the dogs howl eerily. Rain fell like a monsoon and bounced violently off the house and out-buildings, and a large chunk of the jackdaws’ nesting chimney came crashing down. In the morning it lay smashed in the middle of the yard. It had narrowly missed our packed Land Rover.