Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Birlinn

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

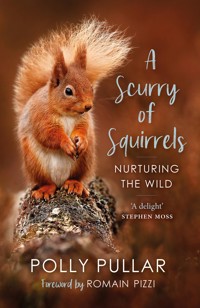

Polly Pullar has had a passion for red squirrels since childhood. As a wildlife rehabilitator, she knows the squirrel on a profoundly personal level and has hand-reared numerous litters of orphan kits, eventually returning them to the wild. In this book she shares her experiences and love for the squirrel and explores how our perceptions have changed. Heavily persecuted until the 1960s, it has since become one of the nation's most adored mammals. But we are now racing against time to ensure its long-term survival in an ever-changing world. Set against the beautiful backdrop of Polly's Perthshire farm, where she works continuously to encourage wildlife great and small, she highlights how nature can, and indeed will, recover if only we give it a chance. In just two decades, her efforts have brought spectacular results, and numerous squirrels and other animals visit her wild farm every day.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 366

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Polly Pullar is a field naturalist, wildlife rehabilitator and photographer. As one of Scotland’s foremost wildlife writers, she contributes to a wide range of publications, including the Scots Magazine, Scottish Field, BBC Wildlife and Scottish Wildlife. Her books include A Richness of Martens – Wildlife Tales from the Highlands and The Red Squirrel – A Future in the Forest with photographer Neil McIntyre. She is also the co-author of Fauna Scotica: Animals and People in Scotland.

Described by the Guardian as ‘arguably the most versatile and inventive vet in the world’, Romain Pizzi has operated on a vast range of animal patients. In addition to his work at the Scottish SPCA National Wildlife Rescue Centre, he has appeared on a number of TV documentaries, including Vet on the Loose and Big Animal Surgery.

First published in 2021 by

Birlinn Limited

West Newington House

10 Newington Road

Edinburgh

EH9 1QS

www.birlinn.co.uk

Copyright © Polly Pullar 2021

Foreword copyright © Romain Pizzi 2021Chapter-opening squirrel artwork by Potapov Alexander (Shutterstock)

All rights reserved

The moral right of Polly Pullar to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the

Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

ISBN 978 1 78027 704 2

eBook ISBN 978 1 78885 465 8

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or transmitted in any form without the express written permission of the publisher A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Typeset by Initial Typesetting Services, Edinburgh

Printed and bound by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A.

For Clare, with all my love,andfor Neil McIntyre,

who loves squirrels as much as I do

Contents

Foreword

Introduction

1. The Power of Squirrel Nutkin

2. Bough Lines

3. Cull of the Wild

4. The Arboreal Athlete

5. A Drey in the Life of a Squirrel

6. A Grey Area

7. The Compost Café

8. Care of the Wild

9. Drey in a Lunch Bag

10. For the Love of Trees

11. The Squirrels’ Return

12. Natural Conflicts

13. Ruby

14. Squirrel Tales

15. Squirrel Summer

16. Three Squirrels in a Bookshop

17. Squirrels Go West

18. Letting Go

19. Owls in the Chimney

20. Helen and Pipkin

21. Cloudy

22. Squirrels on the Move

23. Alladale

24. Foresting Hope for the Red Squirrel

Afterword: The Child in Nature

Acknowledgements

The Squirrel

Whisky, frisky,

Hippity hop,

Up he goes

To the tree top!

Whirly, twirly,

Round and round,

Down he scampers

To the ground.

Furly, curly,

What a tail,

Tall as a feather,

Broad as a sail!

Where’s his supper?

In the shell.

Snappy, cracky,

Out it fell.

Anon

Foreword

This book is a fascinating read, filled with anecdotes and wisdom from a life spent closely connected with the natural world. It is also Polly Pullar’s very personal story of habitat restoration on her small Highland Perthshire farm and the benefits this can have for native wildlife species, including red squirrels.

From her deep fascination with nature as a child stuck at boarding school to her ongoing work hand-rearing orphaned squirrels, as well as treating and rehabilitating all manner of animals for release back to the wild, Polly shares her thoughts on the state of nature as a whole. The result is a personal but holistic picture that no academic tome or coffee-table book can offer. We share in her efforts to syringe feed tiny, pink hairless baby squirrels no larger than her thumb and worry with her about how they will fare back in the wild when they are released.

It seems strange to find myself writing a foreword to a book on red squirrels, having grown up in South Africa with its famous ‘big five’ – the lion, leopard, rhinoceros, elephant and buffalo. Squirrel Nutkin bore no resemblance to the Cape ground squirrels I saw. Boisterous khaki characters standing on hind legs and living in burrows, they were more like meerkats than the illustrated squirrels with tufted ears I saw dancing along tree boughs in children’s books. Yet as Polly’s experiences bear testimony, despite their charming appearance – exactly as they are illustrated in Beatrix Potter’s stories – one quickly appreciates the tough lives these acrobatic creatures live. Not only must they survive the harsh Highland winter weather, there is also the constant struggle to find food – all the while carefully evading a host of hungry predators from domestic cats to large birds of prey. These are animals that are indeed wild, in every sense of the word.

Red squirrels now appear that very rare anomaly – a wild animal that no one in Britain maligns. Polly delves into their fascinating history, exploring how our confused attitudes to them have changed over time. It seems difficult for modern readers to fathom the sixpence bounty that was once paid for a squirrel’s tail, and the fact that they were blamed for everything from killing game birds to destroying trees. Due to this misconception, squirrel-hunting societies accounted for the deaths of shockingly high numbers.

Her beautifully descriptive writing transports you into her world – a microcosm of the bigger picture – in which predators are every bit as important as the prey they hunt, despite our misguided human needs to meddle. There are no ‘good’ or’ bad’ animals. They are all part of the natural world, just with different roles to play.

Although their reputation has now been completely rehabilitated, it is sad to realise that more people in Britain have likely seen a rhino in a zoo than a red squirrel, despite their perennial popularity on Christmas cards. And we must not forget that red squirrels are still in perilous decline in the British Isles.

Filled with perception, compassion and empathy, A Scurry of Squirrels is a poignant reminder for us to care for and nurture the wild, before we lose it forever.

Romain Pizzi

June 2021

Introduction

Until one has loved an animal, a part of one’s soul remains unawakened.

Anatole France

I never thought I would see the day when I actually enjoyed washing-up. It has to be one of the most tedious of all domestic tasks. However, standing at our kitchen sink, I gaze out on our wild garden and see red squirrels bounding through the branches, or frenetically chasing one another as they come into the feeders. Friends have described this view as ‘Squirrel Central’. Some days it’s very hard to tear myself away, and I could be accused of not concentrating on the task in hand. You may be surprised to know that you can learn a great deal while you are scrubbing at the pots and pans.

In 2020 my small farm in Highland Perthshire came of age. It is twenty-one years since I bought it for me and my son, who was eleven then, and during that time it has been transformed from an overgrazed and barren hillside into a wildlife haven. As well as a great many free-living wild visitors, I also take in injured or orphaned wildlife received from members of the public or our local vets. My aim is to eventually return them to the wild, and some of these encounters will form an integral part of this story, though this is predominantly a book about squirrels.

I have always adored trees, and have since planted over 5,000, together with numerous hedging plants. I have also created a wild garden rampant with shrubs and flowers, specifically to entice all creatures great and small. Being on a south-facing hillside where we are usually supplied with plenty of rain has suited the trees perfectly. Even if the increasing frequency of our monsoon-style deluges is not always to my liking, for the trees it has been a bonus. The results are spectacular. Friends have often commented that surely I am planting trees I will never witness in their glorious maturity. However, the young trees are already stretching their boughs heavenwards. In two decades we have small, noteworthy woods. It’s something that makes me immensely proud, even though in some areas of the farm, the exuberance of the trees is starting to obliterate the snaking view of the Tay Valley far below. As the trees have grown, and the habitat recovered from years of overgrazing, the red squirrels and numerous other animals and birds have returned.

There are probably few British native wild mammals, other than the red squirrel, that are so universally adored. Mention a long list that includes, otter, stoat, weasel, polecat, pine marten, badger, fox, beaver, seal, roe or red deer, and you are bound to face a wall of negativity. Someone somewhere will give you a tirade relating to the heinous crimes committed by whichever beast is being discussed. Foxes have been persecuted and reviled for centuries; badgers are blamed for almost every evil known to man; stoats, weasels and polecats are referred to as ‘murdering little egg thieves’ and are therefore loathed by game managers, as well as various other members of society. Pine martens fit the same category, and being partial to a chicken takeaway, are often simply viewed as ‘poultry killers’, instead of brilliantly adapted lithe and nimble mustelids with a penchant for mischief. Deer are ruinous to forestry, impede natural regeneration, and spoil the garden. And beavers, well these large reintroduced rodents are either worshipped or condemned, whichever side of the fence you perch. We have no cultural memory of the beaver’s presence in our midst, and it is taking some a long time to accept the positive aspects of this extraordinary, keystone aquatic ecosystem engineer.

Though we are supposedly a nation of animal lovers, when it comes to wildlife we have preconceived ideas and like things to be orderly and to fit neatly into a category; they must be sanitised and convenient. We don’t want to witness any behaviour that shocks us or seems distasteful. When that is not the case, then I am ashamed to say that humans are the most efficient and destructive killers on Earth. We wrongly classify our wildlife as good or bad, vicious or gentle, and are unable to accept that we need predators just as we need prey. For centuries we have mercilessly hunted, poisoned, trapped, snared and shot, and despite current legal protection for a whole host of species, illegal persecution still continues.

It’s sadly true that if nature disrupts our lives then we endeavour to get rid of whatever it is that is causing disruption or not fitting in with our plans, in the mistaken belief that its removal will resolve the issue. However, nature hates a void, for every living thing would slot seamlessly into the bigger picture if we only let it. As soon as there is an imbalance then the entire ecosystem is unable to fully function. As we are witnessing every day through the negative world news that floods our inboxes, radios and televisions, we have pushed the natural world to the brink of total collapse.

Though you will always find someone somewhere who will tell you a damning story about a particular animal or bird, I have yet to find anyone who says anything negative about the red squirrel. It is a fine example of a British mammal we would neatly slot into our ‘good’ category. Little wonder, for this glorious little arboreal gymnast instantly intoxicates us. It exudes charm, fun and devilment, it is playful – almost elfin – and instils awe as we watch it dancing around the woodland canopy. It has an enchanting little face, a beautiful coat of burnished red that glows gold in sunshine, and a superb bushy tail that it can use in numerous ways, including as a parasol or umbrella. Its little ears are often fringed with dramatic tufts that make it look as if the wearer has used the crimping tool on the hair dryer. In this country we love red squirrels with a passion; they are high on the list, often on the top of the list, of the species we most want to see. However, what is shocking is that this was not always the case.

As we struggle to protect and safeguard our small remaining population of red squirrels, it is hard to accept that up until 1981, when they received full legal protection under Schedules 5 and 6 of the Wildlife and Countryside Act, it was perfectly legal to cull them. And they were culled in such large numbers that we almost wiped them out altogether. In fact in some areas we did just that, and even now, due to loss of habitat, urbanisation and an everincreasing road network, it is likely that many traditional red squirrel haunts have since become so ruined, or lost altogether, that they will probably never again be re-colonised by red squirrels.

Perception is a curious aspect to human nature. And everyone’s perception varies. It’s this that makes the way each of us in turn relates to the wildlife that surrounds us so complex. It’s much the same with our incredible native flora – we battle endlessly against dandelions, which are not only flamboyantly beautiful, but most importantly are vital to pollinators including the species we love – bees, butterflies and moths – and replace them with expensive plants from garden centres that often are far less rich in nectar. In nature there is no such thing as good and bad: each living thing, great or small, is part of the magnificent jigsaw that is life itself. The red squirrel is a vital piece, and without it, that jigsaw is incomplete.

The red squirrel has always been up against it. For far too long our forebears believed that it was simply another pest, because of the perceived threat it posed to forestry. It needed to be obliterated at every opportunity. Less than a century ago, the squirrel was viewed with much animosity, but now we have taken a 360-degree turn, and the nation’s swiftly dwindling red squirrel population is relishing a rebirth as one of the country’s favourite mammals. Yet our darling red squirrel is not perhaps as angelic as it might appear, and many are surprised to learn that it too can predate, and is not averse to occasionally filching eggs or fledglings from an unguarded songbird’s nest. Protein is an important part of its diet.

I have been fortunate to come to know and love the red squirrel from a very personal angle. I am constantly learning about its fascinating ways, its nature and its natural history. The more I learn, the more I realise that there is so much more to discover regarding these woodland specialists. Through working closely with squirrels, as well as a wealth of other mammals and birds, perhaps the most important thing I have learned is that time is fast running out and if we do not restore and protect valuable habitat, then this enchanting little rodent, and dozens of other species, may be lost and gone forever.

1

The Power of Squirrel Nutkin

I was always a child of nature and was extremely fortunate to spend part of my early childhood in one of the richest wildlife areas of the British Isles. There can be little doubt that I owe my parents an enormous debt of gratitude for living in some of the glorious places that they chose as home. Being steeped in nature from as far back as I can remember has helped to forge my undying, lifelong passion and my way of life as a writer and photographer in a bid to help others discover that precious connection with wildlife.

Fifty miles due west of Fort William lies the rock-hewn Ardnamurchan peninsula. This, the most westerly mainland point in the country, is a place of savage beauty, diverse in its land and seascapes, surrounded on clear days by sweeping views to the Western Isles, and to some of Scotland’s great mountain vistas, including the Skye Cuillin, Knoydart and the wind-scoured ridges of Torridon. Gale-battered Atlantic oak woodlands fringe the peninsula, providing an unsurpassed environment for a host of living things including rare invertebrates, flora, mosses and bryophytes, as well as fabulous fauna: red deer, golden and sea eagle, wildcat, pine marten, otter, fox and badger. Though at the end of the 1960s I grew up surrounded by an unequalled diversity of wildlife that I often encountered on a daily basis, the red squirrel was missing.

However, the red squirrel has been a part of my psyche for as long as I can remember, because I was reared on the tales of Beatrix Potter, and count these as amongst the very finest works of children’s literature. They are highly entertaining for grown-up readers too. The fact that Potter wrote the stories and created the artwork is important. The marriage of words and pictures is unsurpassed. Her illustrations are entrancing, and often skilfully humorous. Though in most cases she anthropomorphises her animals, and her stories depict them behaving like us while dressed in clothes, her shrewd naturalist’s eye ensures that each is perfectly portrayed, with an attention to critical detail that reveals very real facets of its wild character. Undress her subjects and what lies beneath is astonishingly accurate. Squirrel Nutkin has long been one of my favourite Beatrix Potter figures. Like most of the handreared squirrels I have been fortunate to spend time with, Nutkin is a little devil overflowing with mischief and playfulness.

When The Tale of Squirrel Nutkin was published in 1903, naturalist Potter probably had no idea that her brilliant squirrel portrayals and her clever words would be a catalyst that began to change our point of view. Some fifty years later, another red squirrel was a crucial player in the evolution of our attitudes towards red squirrels. Tufty became the figurehead for a road safety campaign aimed at small children. When I was six years old I was made a member of the Tufty Club and wore my badge with pride. I still have it. Now when I see an increasing number of pathetic little red squirrel bodies dead on our busy roads, it is heartrending to witness that the Tufty Club’s wise message for children can do nothing to protect the vulnerable relatives of its cult hero.

It was not until I was nearly nine and sent away to a small all-girls boarding school set on a wooded Perthshire hillside at Butterstone, near Dunkeld, that I began what has since proved to be one of my wildlife love affairs.

Hating being away from home and suffering from acute homesickness and the instabilities surrounding the pending separation and subsequent divorce of my parents, to the staff I must have been the problem child. I was more intrigued by the birds in the garden than the lessons and I was permanently crying because I missed home and our family’s large menagerie so much. A finicky eater, I hated the school food too: stodge, stodge and more stodge. We were not allowed to take food back to school with us but we could take birdseed and nuts to put out on various bird tables in the grounds, and I constantly asked my parents for more supplies. I sometimes got so hungry, having been repulsed by the proffered meals, that I ate the birds’ food to stave off my hunger pangs instead. Nuts have remained a favourite food ever since. Compared to the freedom I had experienced in Ardnamurchan, now there was a strict new regime and there were also two ‘big’ little girls who were bullies, and who teased me incessantly. I simply wanted to go home. When I look back over it, I realise that Butterstone was not a bad place. Its setting is idyllic for a nature-loving child, as it is surrounded by oak woods and freshwater lochs where I quickly discovered that there was plenty to take my mind off my yearning to go home.

My inauguration at boarding school began in September. I remember that for the first few miserable days after term had begun, it rained incessantly. I kept diaries – hardly literary gems: ‘It rained again. Missed mummy, Ginger (my pony) and the dogs. School food is horid. Bridget said she might be my frend.’ An Indian summer then followed this damp tear-soaked start, with balmy days that made the landscape glow as swathes of rosebay willowherb set loose their fluffy seed heads to float in the breeze. The surrounding forests blended to a palette of yellow, ochre and bronze, and jays shrieked as they flew in bounding flight on their acorn-collecting forays, filling the air with the sound of tearing linen. Then one morning at break time when we were playing in the garden I saw a red squirrel swinging on the peanut feeder of our bird table. I remember it vividly because instantly it seemed so similar to Squirrel Nutkin, particularly as it then leapt onto the table and sat up to eat, holding nuts in what I saw as its perfect little furred hands. That night my diary entry read: ‘Saw my first squirel – it is so beautiful I cannot believe it. It looked Soooo like Squirrel Nutkin.’ And thus began another journey.

My homesickness began to ease and I even found myself eagerly anticipating playtimes so that I could go out into the garden and the school’s extensive surroundings to look for squirrels. They were plentiful and the more nuts we put out, the more seemed to come. They were often there very early in the mornings but there was never time to go out before breakfast, and by the midmorning break time they had usually gone. They had a routine and after an early start they returned at lunchtime and then again at teatime, but in winter as the days became shorter and shorter, their visits tended to be harder to time.

In the early mornings and late afternoons, fallow deer emerged shyly from the shadowy woods too. Though I was very familiar with our two native deer species in Ardnamurchan – the red and the roe – I had never seen fallow before. Their four colour variations intrigued me: common – rusty brown with speckles; leucistic – a pale cream colour; menil – with spots and dark brown around their tails rather than black; and melanistic – a really dark brown form. The gardener always complained that they ate his flowers. Sometimes he mumbled and grumbled because they also left little heaps of shiny black currants around the grand front door entrance. It always made me giggle. I had a pet sheep back home called Lulu and she did the same thing around the doorways of my parents’ hotel in Kilchoan. Only sometimes she also went right upstairs and left currants outside guests’ bedrooms. This was unappreciated.

We were allowed to build dens in the huge grounds, and the rhododendrons and an unruly stand of bamboo made perfect places for foundations for superb structures. However, I usually played by myself and made dens further out on the edge of the garden specially for watching the red squirrels and the fallow deer.

Living in such a beautiful landscape meant that nature education was a positive and prominent aspect to our time at Butterstone. We had a large nature table and were encouraged to bring things in for everyone to share and talk about. I asked cook for a jam jar with holes in its lid so I could keep a chrysalis I had found and we could watch it transform into a lovely moth. I excelled at nature education, art, English and reading, and was pretty bad at everything else because I found the teachers boring. We could also watch the birds and other animals from the windows, and even had walks into the out-of-bounds areas of the woods in spring to listen to birdsong. By May the cuckoo would arrive, and once I saw a tiny willow warbler struggling to keep pace with the gluttonous appetite of its obese fostered cuckoo chick. So though to begin with I hated being away from home, there were bonuses.

There were also regular school outings to nearby Loch of the Lowes. The Scottish Wildlife Trust purchased this nationally important wooded wetland site in 1969 and it has since become their flagship reserve and is in particular famous for its breeding ospreys. Soon after the purchase, a pair of ospreys conveniently turned up. On my initial school visit the spring after my first term, small groups of us were allowed to clamber up into a shoogly hide built on stilts to watch these magnificent fish-eating raptors. Without proper binoculars or telescopes at that early stage of the reserve’s development, and no cameras on the eyrie, it was primitive compared to the way every midge, every buzzing fly, the piping of an egg as it begins to hatch, and the diamond beads of raindrops on a sitting bird’s ruffled feathers can be viewed today right around the globe by anyone with internet access. While the ospreys were fascinatingly exciting, particularly as the reserve’s warden related the story of how these migrating birds that returned to Scotland to breed in spring had been persecuted to near extinction, it was the red squirrels that captivated me. At Loch of the Lowes some of them were so tame that they would come and take peanuts from our hands, providing we kept very still and quiet. When it involves wild things and wildlife-watching, oddly, though I am told I am a keen talker, I have never had a problem with keeping quiet. The squirrels in the school grounds were wisely wary. This was no surprise, given the racket made at playtime by a lot of shrilly shrieking little girls. However, I realised that if I broke away on my own from the team games we played in the garden, and instead went off to the woodland fringes and hid myself in my den, it was different. There I put out food on the old crumbling drystone wall, and the squirrels began to venture in closer and closer. I soon attracted enchanting little wood mice and bank voles too. One day a weasel popped its foxy little face from out of a mossy hole in the wall. Its body was like a piece of elastic. I began to recognise individual squirrels and could see that each was unique, that its mannerisms and the particular way that it interacted with the other squirrels was different too. Some had very blonde tails and flamboyant ear tufts, while others had lost these wonderful extra head adornments. Most of them preferred to be there alone and would not tolerate imposters on this new food supply; they clearly were under the impression it was theirs entirely. Squirrels are no different to people, and each has a unique character and its own particular behavioural traits. Some were more tolerant than others but in most cases, if another squirrel dared to try to venture in then it was swiftly chased away with a flurry of angrily waving tail and loud squirrel bad language. Incidentally, red squirrels have quite a temper. They are also surprisingly vocal, and won’t hesitate to let you know when they are displeased, or particularly content. With fast tail flicking and irate chitter-chatter, an imaginative watcher can easily translate this to a squirrel’s version of ‘go forth and multiply’, for that is exactly what they mean. Some of my little visitors quickly became bolder and bolder, and bounded up close to me, while others remained edgy. It filled me with a frisson of excitement that I still feel every time I view any wild thing from a close perspective.

The gardener had a large cat, and one morning it narrowly missed catching one of the squirrels as it was burying nuts on the lawn. Sometimes that damn cat would appear with birds poking from its gaping jaws, pathetic little feathers soggy with feline spittle. And it tortured and teased mice, patting at them with its fat paws, and sometimes throwing them into the air before it finished them off. And worse still, one wet morning I saw to my horror that it was carrying a squirrel’s tail. I began to hate that bloody cat, and got into trouble for referring to it as such to one of the teachers. I was made to write pages of pointless lines that said: I must not swear, because it is rude. I have been worrying about the effects of domestic cats and dogs on squirrels ever since. Though squirrels are nature’s finest trapeze artists, they are sometimes woefully un-streetwise when on the ground and come to grief all too often.

When my parents – separated by now – independently came to take me for sporadic day’s out from school, it invariably included a visit to Loch of the Lowes. I had told them that the squirrels there would feed from our hands. They certainly enchanted my father during a visit one afternoon in late autumn when we were lucky to watch several of them having a final feed before they vanished back to their dreys for the night. One of them landed on his bald head. Afterwards we sat in a hide in the pinkly transforming dusk as smoky trails of mist spread over the loch, drinking tea from his thermos flask to the accompaniment of the cacophony of hundreds of wintering greylag geese splashing down onto the water to roost. That Christmas holiday I went to spend a few days with Dad. Following my parents’ separation, he had moved temporarily to London and he took me to see a ballet, The Tales of Beatrix Potter. Squirrel Nutkin’s performance on stage left me in no doubt that with the exception perhaps of the rare great crested grebe, a bird I had also seen at Loch of the Lowes, the red squirrel was indeed the finest dancer in the natural world.

2

Bough Lines

The red squirrel has been in the British Isles for a very long time. Fossil remains found at the end of the last Ice Age from some 12 million years ago reveal a similar mammal to the one we now know. The Latin name of the red squirrel is Sciurus vulgaris and the name squirrel comes from the Greek skiouros, meaning a shadow, and oura, a tail – shadow tail. Old local names are more prolific south of the Scottish border and include scorel, squerel, skuggie, squaggie, skoog, swirrel, squaggy, scrug, skarale and scuggery. These are likely to have evolved through the different pronunciations of our richly diverse regional accents all around the British Isles. Puggy has little similarity to the others but often appears in old documents. When I was at school and first encountered squirrels we used to refer to them affectionately as squigs, and the name has stuck. I still find myself using it on occasion as in, ‘I am just going out to feed the squigs.’

The red squirrel’s Gaelic names are feòrag and toghmall. Though the translation may be hazy and open to various interpretations, some of which refer to its woodland home, the best and most appropriate is ‘the little questioner’. Given the extraordinary inquisitive nature of the squirrel, this translation fits it perfectly.

The French word for squirrel is écureuil, and in German it is Eichhörnchen or Eichkätzchen – literally meaning oak kitten, a name that aptly depicts an animal with an incredibly playful ‘kittenish’ spirit that is also often associated with oak trees. We use the term ‘squirrel’ as well as ‘magpie’ to describe someone who hoards or collects things. This is due to the squirrel’s habit of caching and burying food for the winter. We ‘squirrel’ things away – special food items or perhaps precious items we don’t want to share with others. Incidentally, the magpie has been known to steal items of shiny jewellery that have been left close to open windows, but the squirrel does not have the same attraction to such things. Use of the word ‘con’ for a squirrel is commonly found in dusty Victorian natural history tomes, and was employed in parts of England as well as in Scotland.

Collective nouns for animals and birds have always fascinated me. For squirrels it is a scurry, or occasionally you may find reference to a drey of squirrels too – which does not seem very imaginative, given that this is the name of their nest. However, I have often thought that a knot of squirrels would also be appropriate. Having hand-reared numerous litters of kits, when they are asleep together they become so entwined that it can be impossible to see which body part belongs to which little squirrel as they bind themselves tightly together as if in a beautiful tight knot.

Considering the long love-hate relationship that has surrounded the red squirrel, it is perhaps surprising that its association with folklore appears to be largely non-existent. Squirrels do, however, feature as heraldic symbols and their presence on a coat of arms, usually sitting and holding a nut or acorn, is thought to symbolise caution, thriftiness and conception. Depictions of squirrels as heraldic symbols were far more prevalent for families from the north of England; although the Earl of Kilmarnock – family name Boyd – had two squirrels on the family coat of arms, and squirrels also occur on the seal of Robert Boyd, Lord of Kilpoint in 1575, their presence for a Scottish family is thought to be unusual. While mammals such as the hare have always been revered and feared, viewed as totems, signs of good fortune, and conversely of impending doom, given both our turbulent relationship with the squirrel and its numerous charms, it seems odd that it has not captured people’s imaginations in the same manner as other animals.

Ever since its arrival in Britain around 10,000 years ago, it would seem that this is an animal that has always been battling for survival. It has come dangerously close to extirpation on far too many occasions. Much of this is due to a constantly changing woodland environment, but disease and relentless persecution have played their part too. While species such as our largest land mammal, the red deer – also primarily a mammal of woodlands – can adapt to a life without trees, this is not the case for the red squirrel. Without healthy forests, red squirrels stand no chance.

The sylvan history of the British Isles is one of frequent deforestation. Since Neolithic times woods have been harvested, replanted, and often cleared entirely, initially to make way for early pastoral and agricultural activities. In the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries major timber-felling pushed squirrels to the edge, and during this era they vanished entirely from Ireland. In some places woods were even purposely razed by fire. Some were torched to drive out enemies during battles. Other enemies included the wolf. Before it was annihilated from our midst during the eighteenth century, tragically entire forests might also be burned in a bid to kill it. Inevitably, it was not only the wolves that came to a brutal end.

More recently, during the two world wars intensive tree felling for the war effort led to further deforestation on a gut-wrenching scale. During these dark periods of our history, many of the country’s finest native woodlands were lost, together with a host of specialists, including the great grouse of the woods – the capercaillie. Though Lord Breadalbane subsequently reintroduced capercaillie in 1837 to pinewoods on his Taymouth Estate in Highland Perthshire, where for a time they appeared to thrive, it once again faces extinction here in Scotland. The demise of our ancient woodland cover has been progressive and continuous. Sadly, that trend has not changed.

In Scotland, the fall of the extensive boreal forests was to entirely transform the landscape. We became accustomed to seeing vast open tracts of moorland and to view these wet deserts as the norm. Even now we continue to see them as savagely beautiful. This is the real Scotland. This is Scotland in the raw. But is this a commensurate reflection of what would once have been here? Previously, in many parts of the country, a richness of native trees including Scots pine, oak, ash, hazel, willow, birch, juniper, rowan and holly would have spread their lush mantle to cover glens and valleys, painting entire hillsides with a palette of glorious hues that altered through the seasons. These were places that provided a vibrant mosaic of mixed habitat, supplying food and shelter for a myriad of species, including the red squirrel.

An old saying states that a red squirrel could once travel freely from Lockerbie to Lochinver without ever touching the ground. All around the country there were similar sayings, including this one from the Cotswolds – A squirrel can hop from Swell to Stow without resting his foot or wetting his toe, and another from Cheshire – From Birkenhead to Hilbere a squirrel could go from tree to tree. Even if statements such as these are only partially true, they highlight the extent of our sylvan losses all around the British Isles. For squirrels and numerous other specialists, natural wooded corridors, as well as extensive native woodland and hedgerows of mixed ages, hold the key to their survival.

When I speak about woodland and the pressing need for continual planting, I am frequently met with the response, ‘but there are plenty of trees, so what are you making all the fuss about?’ And as we travel around the country we may indeed be under the illusion that there are woods everywhere, and that therefore they must be brimming with wildlife. We may be forgiven for thinking that vast tracts of land lost under the cover of tightly packed dark trees means that we have plenty of forest. But the hard fact is that only 13 per cent of the UK’s landmass is forested compared to 37 per cent of Europe. In Scotland, only 19 per cent of the country is wooded, but worse still only approximately 4 per cent of that consists of native woodland. It’s a very low figure. Worryingly low.

The arrival of commercial forestry might have been seen initially as a positive aspect to our woodland history, but in some cases due to the attraction of government tax break initiatives during the 1970s and 1980s, it led to blanket planting regimes with nonnative conifers such as Sitka spruce. This was to prove detrimental to most species. With their uniform ranks, and fast-growing habit, all light was quickly excluded. In such conditions a forest floor, usually so fecund and dynamic, transforms to a sterile and uninviting environment. Without a healthy understorey and vibrant plant and insect communities, few animals and birds are able to exist. If you are unaware of these problems you may think that commercial planting schemes provide havens. The truth is that the exact opposite is the reality. I think of red squirrels as litmus paper indicating the health of our environment. If the habitat is right for them, then it will be right for numerous other species too.

With such paucity of suitable habitat, current estimates as of 2020 suggest that there are only around 140,000 red squirrels in the UK. And it’s a number that continues to fall. However, counting red squirrels is not the easiest task, and it’s certainly difficult to be accurate, so this figure is indeed at best only an estimate. It could even be far lower. Scotland remains their stronghold and holds the bulk of 75 per cent of the population.

In England and Wales red squirrels are just about managing to cling on by their sharp little claws, and are still found in small, vulnerable populations, including those of the Isle of Wight, Anglesey, and Brownsea Island, and there have been introductions to a few other safe islands; there are reds in some woods and forests of Northumbria and Cumbria. Positively, commercial forestry is now changing and new woods that are grown specifically for timber are a diverse mixture that includes important native trees too, providing bough lines to help enrich the wooded environment.

Countrywide, it’s not only the loss of valuable verdant native woodlands on which the squirrel and a host of other specialists depend that has led to the current decline. The situation is complex, and there are many other serious threats too. For centuries the red squirrel has indeed ridden a roller-coaster. Inevitably, there have also been natural population crashes, due largely to weatherrelated circumstances: winters of deep snow, or protracted periods of ceaseless rain, all of which make life for a fragile little squirrel extremely challenging. However, in these instances, when the population has plummeted, numbers will eventually begin to build up naturally again when climate conditions and food availability, particularly the production of suitable tree seeds, are conducive.

Life for the red squirrel then is far from certain, and it is likely that we will continue to hear both good news and bad regarding its situation. Our hopes for its secure future may be raised and then we are made aware that it is facing yet another seemingly insurmountable obstacle simply in order to maintain its numbers. Currently, population expansion in many areas is challenging, despite the dedicated work carried out by squirrel groups and conservation bodies all around the country who are constantly trying to improve the situation.

As is usually the case with most problems for wildlife, it is humans who continue to have the greatest impact on our native squirrel population. With the ceaseless industrialisation of our landscape, and the continuing sprawl of the urban environment, an everincreasing road network and the insidious threat of the introduced North American grey squirrel that now numbers an astonishing estimated 2.5 million, the red squirrel has much to contend with. Roads account for the deaths of many thousands of animals every year, and young squirrels are particularly vulnerable. In some areas, rope bridges slung high across trees on either side of blackspots and known squirrel crossing areas can help, but fabrication and erection costs are high, and sadly often councils are not prepared to invest heavily when the population of squirrels in a given area may already be low. What price a squirrel? Often concerned locals and wildlife groups work hard to raise funds or to campaign for special squirrel signs, or rope bridges to be put in place. Even if only a handful of squirrels are saved, then surely it is worth it? Recently, lifelike model squirrels placed close to the road edges have been found to slow some drivers – but not everyone is either that observant, or that caring. In some cases these models have also been stolen.

It is vital to remain positive, though I admit often to finding it extremely hard. In Scotland, we now recognise that the beautiful contorted wind-blown ‘granny’ Scots pines that we see on postcards and calendars are in fact trees that have come to the very end of their long lives. Some may be so old that they have even witnessed the presence of the wolf. If only they could tell us of the incidents that they must surely have seen. The pressures of overgrazing from too many deer and sheep mean that these primeval pines cannot naturally regenerate without our intervention. We are beginning to acknowledge the need for a rich forest network, including the need to plant mixed hedgerows to provide habitat connectivity that can help our precious wildlife to travel in safety to find food, shelter and a mate. All over the British Isles, a growing number of charities, as well as private landowners and individuals, are carrying out exemplary work to reinstate natural ecosystems.