Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Birlinn

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

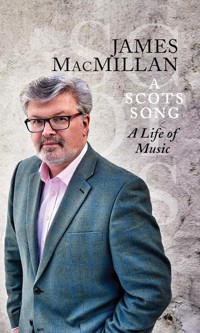

Sir James MacMillan first burst into prominence in 1990 with The Confessions of Isobel Gowdie. A steady stream of works has followed, with commissions from many of the world's major orchestras. A prominent part of his work is his religious composition, which includes settings of both the John and Luke passions, Tu Es Petrus (for the 2010 papal visit to Britain) and numerous smaller choral pieces. His works are heard all around the world – Seven Last Words from the Cross has been performed in 24 countries since its premiere in 1994, and his Stabat Mater received a private performance at the Sistine Chapel in 2018. He is a trenchant commentator on a wide range of political, social and theological issues, many of which spring from his commitment to the cultural life of Scotland. He is a passionate advocacy of community involvement in music and set up the burgeoning music festival The Cumnock Tryst in 2013. Much of his music reflects his strong Scottish roots and interest in all aspects of musical tradition.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 82

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

A Scots Song

First published in 2019 by

Birlinn Limited

West Newington House

10 Newington Road

Edinburgh

EH9 1QS

www.birlinn.co.uk

Copyright © James MacMillan 2019

ISBN 978 178885 225 8

The right of James MacMillan to be identified as author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form or by any means without permission from the publisher.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Designed and typeset by Mark Blackadder

Printed and bound by Clays Ltd, Elcograf, S.p.A.

Contents

Chapter 1Musical Roots

Chapter 2Polyphonies

Chapter 3Finding a Voice

Chapter 4The Search for the Sacred

Chapter 5The Accompaniment of Silence

Acknowledgements

For Lynne, Catherine,Aidan and Clare

Chapter 1

Musical Roots

Mass can be pretty tedious for young kids, and by the time I was five or six, I was bored with my weekly practice at home. I could never see very much, for a start, apart from the backs of heads, and I used to crawl around my parents’ legs, creating mayhem and mischief with my sister Suzanne. In the 1960s, we used to visit my aunt and uncle in Edinburgh, and it was at Mass in St Mary’s Metropolitan Cathedral in York Place that I was struck by something different and unusual – a ghostly, distant and affecting sonic concoction that gripped my childish attention. I strained my neck above the crowd in the pews in front of me. I couldn’t see much from the back rows, but what I heard was clearly connected to the hazy images I could just make out at the other end of the building.

What could I see? Stylised movements of adults and children in robes, clouds of smoke and actions of devotion that I didn’t yet comprehend. The sound was accompanying, facilitating. Looking back on it, and knowing now what liturgy is, I must have been hearing polyphony and Gregorian chant.

I later discovered that the choirmaster at St Mary’s in the 1960s was none other than Arthur Oldham, founder of the Edinburgh Festival Chorus and a friend (and the only composition pupil) of Benjamin Britten. He had come to Edinburgh and converted to Catholicism a few years before I visited the Cathedral. He then took up the directorship of the Cathedral choir, which, under his charge, had become one of the finest in the land, impressing the likes of Carlo Maria Giulini and Georg Solti, who invited the choir to perform at the International Festival. Oldham was one of the first musicians in Scotland to reintroduce Scottish pre-Reformation music such as Robert Carver’s 19-part motet O bone Jesu, and he gave the first Scottish performances of Benjamin Britten’s Missa Brevis.

Considering what I was to do with my own life in the decades ahead, these unexpected formative early encounters with music in the Cathedral seem like happy accidents. I’m writing this short book as I approach my sixtieth birthday and look ahead to August 2019, when the Edinburgh International Festival will celebrate my music and my long-held relationship with the Festival through a series of special performances across the city. My childhood experiences in Edinburgh and, in a more sustained way, back home in the working-class communities of Cumnock and East Ayrshire were seminal for me, shaping and moulding much of what I have done in my music and in my other activities, and in how I have thought about life and art in the years since. In this book, I want to share the things that have proved vital in my work – an inescapable search for the sacred, the role of religious practice, tradition and identity, the influence of political motivation, for good or for ill, and the importance of music in the communities I hold dear.

* * *

Music and spirituality are very closely entwined. They have a centuries-long relationship through the Church, and some of the great music of our civilisation has been written for divine worship. But even in modernity, when the master–servant contract between ecclesial authorities and composers has been broken, music continues its reach into the crevices of the human–divine experience. Music has the power to look into the abyss as well as to the transcendent heights. It can trigger the most severe and conflicting extremes of feeling, and it is in these dark and dingy places – where the soul is probably closest to its source, where it has its relationship with God – that music can spark life that has long lain dormant.

Some claim that all music is sacred, not just the stuff that is written for liturgy. When people, including agnostics and atheists, say that ‘music is the most spiritual of the arts’, they are accounting for the impact it has on their lives – its power to affect not just emotions but also relationships and ways of seeing the world, and the events which mark our individual and personal journeys. Music is able to ‘speak’ to the soul in a way that goes beyond what words and images can convey. I continue to have a relationship with the Church – I write music for its liturgy, but it’s not the main thing I do in my life. I spend a lot of my time with non-religious music-lovers with whom I share a fascination for and devotion to serious music. We are involved in a joint journey of discovery which takes us somewhere beyond ourselves, and which allows us to see ourselves as significantly more than the sum of our parts. Is that what makes music spiritual? No doubt we will have many different perspectives on this.

My instinct is that the secular and the sacred are inextricably connected, and that for me, my journey as a composer began in those distant snatches of Gregorian chant and Palestrina motets which floated down from the sanctuary of St Mary’s in the mid 1960s. I have a special place in my heart for plainchant. It has a timeless, numinous and soothing quality, of course – a kind of perfect, unending melody. And I am not surprised it has gained renewed popularity in the secular world. In the Western art tradition it has always been the root of music, inspiring composers from the Middle Ages onwards and shaping the nature of the song of the Church for centuries.

Even in the modern world, chant continues to inspire. My old friend and mentor, the now departed Peter Maxwell Davies, always had a copy of the Liber Usualis (the major compendium of Gregorian chant) on his desk. He was proud of this. He would delve into it, just for musical and spiritual sustenance, and sometimes music would emerge from his contemplations of it. He was no friend of the Church but, like many secular music lovers, he respected the roots of our musical, artistic and philosophical culture in Judeo-Christian civilisation.

My own rootedness in this civilisation had a lot to do with my family and the small community of Catholics in the Ayrshire mining town of Cumnock. The core of this community was the local parish church of St John the Evangelist, designed by William Burges for the third Marquess of Bute and constructed between 1878 and 1880. My parents were both baptised in St John’s as children and then married there in 1958. I was baptised there a year later, received the other Sacraments throughout the 1960s and played the church’s organ as a teenager.

The local primary school of St John’s had been served for decades throughout the twentieth century by the Sisters of the Sacred Hearts of Jesus and Mary. They educated me and, most importantly, arranged for Miss Gray, our classroom music teacher, to distribute a batch of plastic recorders to the children of Primary 5 one day in 1968. This event was like a light going on for me; from that day I knew I wanted to be involved in and create music. It wasn’t long before I was playing the piano, the trumpet and cornet and being pressed into service by the nuns at St John’s to accompany classroom hymns.

Central to my early encouragement in music was my maternal grandfather, George Loy. He was a coal miner all his life, like many men in the area, and spent his fifty-odd working years underground, but his main passion was music. He played euphonium in colliery bands and was a dedicated choir member at St John’s all through the 1930s, ’40s and ’50s. He introduced my mother Ellen to music when she was young, and she studied the piano and played until she married my dad. But her heart was never really in it. So when I came along, my grandfather was greatly pleased. He got me my first cornet and took me to band practices in nearby Dalmellington. He was keen for me to start playing the organ for Mass and bought me a basic organ tutor and a set of hymn books, which were pressed into service in due course.