Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Amalthea Signum Verlag

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

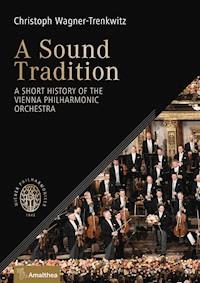

From Vienna into the World What would Vienna be without the Philharmonic? 175 years have passed since the founding of this world-class orchestra in March of 1842, 175 years in which the musicians have provided their public countless glorious musical experiences. Their inimitable and unmistakable sound has aroused truly rapturous enthusiasm everywhere. Christoph Wagner-Trenkwitz tells us of the milestones in the Philharmonic's history—collaboration with great conductors, the special quality of the "Viennese sound," the daily work of an international orchestra—and in so doing unearths memorable anecdotes from behind the scenes. With extensive illustrations and photographs from the Vienna Philharmonic archive

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 256

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Christoph Wagner-Trenkwitz

A Sound Tradition

A SHORT HISTORY OF THE VIENNA PHILHARMONIC ORCHESTRA

Translation from the German by John Hargraves

With 99 illustrations

To the memory of Ernst Ottensamer (1955-2017)

Visit us online at amalthea.at and wienerphilharmoniker.at

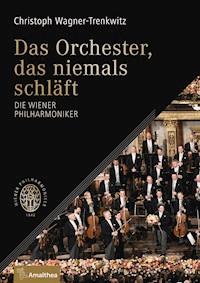

© 2017 by Amalthea Signum Verlag, WienAll rights reservedOriginal title: Das Orchester, das niemals schläftEditing: Murray G. HallCover Design: Elisabeth Pirker/OFFBEATCover photo: The New Year’s Concert 2017,conducted by Gustavo Dudamel © Wiener Philharmoniker/Terry LinkeGraphic Design: VerlagsService Dietmar Schmitz GmbH, HeimstettenTypeset in 11,5/15 pt Minion ProDesigned in Austria, printed in the EUISBN 978-3-99050-109-2eISBN 978-3-903083-85-1

Content

Foreword

Andreas Großbauer

Greetings

Heinz Fischer

The Vienna Philharmonic Society

Marifé Hernández

A Tour

A Stroll through Vienna and through the History of an Orchestra

Old and New Home

Founding and Establishing the Orchestra (1842-1870)

The “Golden Era“…

…began in the Golden Hall (1870-1897)

Mahler and the Consequences

The New Century (1897-1933)

The Burden of History and the Dawn of a New Age

Fascism, War and Reconstruction (1933-1955)

Sound and Tradition

What Makes the Vienna Philharmonic What It Is

“How Do I Get to the Philharmonic?”

And: How the Philharmonic Got to Where It Is

An International Orchestra

Today and Tomorrow

The Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra

Members in the Jubilee Season 2016/2017

Literature

Photo credits

Index of persons

Foreword

This year, the year of 2017, our orchestra is celebrating a special birthday. One hundred seventy-five years ago the Vienna Philharmonic was founded in Vienna, that city of music which has always attracted and been home to important composers and musicians. This anniversary is an appropriate occasion to trace the traditions and present-day challenges of our orchestra in a literary way. The well-known Austrian writer on musical matters, Christoph Wagner-Trenkwitz, has taken on this task, and with the present book A Sound Tradition he has written a short history in facts, pictures and anecdotes. (The German title is Das Orchester, das niemals schläft—The Orchestra that Never Sleeps).

This same vitality that he ascribes to the orchestra in the original title is evident in his book. For Wagner-Trenkwitz takes his readers on a journey in a very charming and knowledgeable way. This way first leads us to a place where the orchestra was founded and which appears in the name of the orchestra as a sort of seal of quality: Vienna. If you take this walk through Vienna with the author you will meet music at every turning, and wherever you meet music, you will also discover traces of the Vienna Philharmonic.

But this journey with the orchestra leads the reader further: to the cities of Austria, first of all Salzburg, to the cities of Europe and indeed to cities all over the world. Here I would like to emphasize one city above all: New York, where a group of friends of the orchestra have united to form the Vienna Philharmonic Society. Its particular concern is also to celebrate the orchestra’s 175th anniversary in an appropriate way. So the Vienna Philharmonic Society and the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra created the idea for this book together, which is being published not only in German but also in English, so that many people from all over the world can participate in this literary-musical journey.

As the journey leads us to many different places, it also takes us to different times. Wagner-Trenkwitz takes us on a time journey from the orchestra’s beginnings up to the present, and not just as a mere account of dates and facts, but in an informative, anecdotal, and occasionally humorous manner. We are witnesses to the great moments of Philharmonic history, but also to those times when the musicians and their music were caught under the wheels of ideology and racist fanaticism.

The author accompanies us into the world of a Philharmonic player, starting with his/her audition, going through the experience of being in the orchestra pit of the opera and on the concert stage, up through the schedules and challenges of a Philharmonic year. Wagner-Trenkwitz shows us the world of the great conductors and lets us have a look behind the scenes of the Philharmonics’ everyday life with many a delectable story.

One of the special high points of the book is the chapter Sound and Tradition, in which the author takes a closer look at the mythic “Viennese Sound.” The mystery of this acoustic experience is based on many components: the particular instruments, the special approach to tone, the particular kind of vibrato, the requisite orientation to the human voice in sound and phrasing that comes from daily playing at the opera and much more. The special ingredients of their success are the trust that the musicians have in one another and their familial spirit, which in the end are the guarantors of that special sound attested to by many and on which the orchestra’s fame is based.

On the occasion of such a special birthday, it is incumbent on us to remember the beginnings. Whoever knows the principles of our founding fathers, who created the orchestra’s standard of highest artistic quality, its democratic structure and sense of humanitarian responsibility, will understand why we feel bound to honor this tradition. But tradition remains alive only through innovation, and this is true both for its social responsibility and its artistic focus. Thus the book points out the thorough reappraisal of the orchestra’s recent history, the artists’ social responsibility regarding the pressing problems of our time, local and global initiatives for peace and international understanding, the equal treatment of men and women in the artists’ collective, responsibility in creating programs with regard to contemporary music, the international recruitment of the next generation of musicians, and cultural education projects. Numerous activities of this kind show that the Vienna Philharmonic is, in the 21st century as well, an orchestra “that never sleeps.”

Andreas Großbauer

Initiator of the book and

Chair of the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra

in the Jubilee Year 2017

Greetings

The Vienna Philharmonic was founded in 1842. On the other side of the Atlantic, in the same year, without any coordination or consultation, the New York Philharmonic was also founded.

So both orchestras are celebrating their 175th birthdays this year (2017) and have had a close and friendly relationship for a long time—but not exactly since their founding. On March 28, 2017, there was a memorable birthday party for the Vienna Philharmonic at the Haus der Musik in Vienna (with representatives from New York in attendance) under the motto “Music knows no borders.”

That is truly an apt motto. For music, which is not bound to language and which expresses every emotion, feeling, and thought common to mankind, indeed knows no borders.

In a speech I gave at this birthday party, I said that the music of Mozart or Beethoven, and of many, many other composers as well as their interpretations effortlessly crossed the borders into over 200 countries of this world. And more than a few of these “musical border crossings” have had their beginnings in Vienna, in Austria, and with the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra.

Now a birthday party is a wonderful event; but it is just a “snapshot.” For the date of a birthday slowly approaches, we look forward to it, one day it finally arrives, but in a very short time it is behind us again and is gone.

As opposed to that, a book is something lasting, something that one can pick up again and again, can give to someone else, and will have its fixed place on the bookshelf.

Admittedly, there have been excellent books, based on the latest research, that have been written about the Vienna Philharmonic in the last few years. I am especially referring to the standard works of Clemens Hellsberg (1992) and Christian Merlin (2017).

But the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra is an almost inexhaustible topic, and so I was very pleased to hear that Christoph Wagner-Trenkwitz, as an outstanding expert on the music scene in general and the Vienna Philharmonic in particular, has taken his pen or keyboard in hand to write about “the Orchestra that never sleeps” on the occasion of the 175-year Jubilee of the Vienna Philharmonic.

Emperor Charles V. reigned, as we know, over an empire on which the sun never set. When we consider the fact that the Vienna Philharmonic gave 49 concerts abroad in the 2015/16 season alone and were on the move giving these concerts from Japan to the US and from Sweden to Australia, then we can truly say that the Philharmonic members are probably active all the times of the day (Central European time) and thus “never sleep.”

And the best part is that the Vienna Philharmonic in the aforesaid period may have given 49 concerts abroad, but also 89 (!) concerts in Austria, and every single one of them at the highest standard.

I am proud of the Vienna Philharmonic and I wish this book, being published for the 175th Jubilee of this great orchestra, the greatest success.

Dr. Heinz Fischer

Bundespräsident (ret.) and

Patron of the Vienna Philharmonic

The Vienna Philharmonic Society

The Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra is known worldwide for its superb musicianship and unique sound. What is perhaps not as well known is that the Orchestra has a beautiful soul. Whether it is teaching children to play a violin, providing a safe haven for refugees to begin a new life or participating in the observance of a tragic event that must never recur— you will find the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra leading the efforts to help, heal and herald new beginnings.

The Vienna Philharmonic Society was founded in 2016 to help the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra bring its glorious music more often and to more cities across the United States. The Society is also bringing the values and ideals of this remarkable Orchestra to this country. A program of music education has already begun in New York for both public school children as well as advanced students in the music conservatories. That special Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra combination of musical magic and caring has been transplanted to the United States.

It is very moving to see such a talented group of musicians care so much about the problems of the men, women and children around them. Through its music and their strong philanthropy, the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra makes a difference in many lives whether in Vienna, New York or Tokyo.

We invite you to join us as author Christoph Wagner-Trenkwitz brings to life the history and personalities of the Orchestra as it celebrates its 175th birthday. The English translation from the German original is provided by our board member John Hargraves.

Marifé Hernández

Chairman of the Vienna Philharmonic Society

New York, October 2017

THE VIENNA PHILHARMONIC SOCIETY

Board of Directors

Michael G. Douglas

Elizabeth Ingleby

William D. Forster

Nizam Kettaneh

John Hargraves

Cynthia Sculco

Max Jahn

Theodora Simons

www.viennaphilharmonicsociety.org

Even if the orchestra does occasionally sleep, in the Musikverein the golden caryatids still keep watch.

A Tour

A Stroll through Vienna and through the History of an Orchestra

May I interest you in a little tour of the city? In less than twenty minutes, we will stroll by the most important centers of Philharmonic life of Vienna.

Home Base: the Musikverein

Let us begin with the Karlsplatz. Behind us, the baroque splendor of the Karlskirche, Ressel Park with its Brahms memorial, and the Technical University (formerly the Imperial and Royal Polytechnic Institute, where the Strauss brothers Johann and Josef studied). In front of us is the Musikverein building by Ringstrasse architect Theophil Hansen, who also designed the Vienna Parliament building, the Academy of Fine Arts at the Schillerplatz, the Stock Exchange on the Schottenring, and numerous palatial residences of the capital city. The home of the “Society of Friends of Music in Vienna” (Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde in Wien), founded in 1812, also houses the administrative offices of the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra (or as it is called in good old Austrian bureaucratese, the “Chancellery.”) Here, in the Great, or “Golden,” Hall of the Musikverein, since it opened in 1870, the subscription concerts of the Philharmonic as well as the New Year’s Day Concerts take place, which have contributed to its international standing.

Stars are set into the paving stones in front of the façade with the names of important musicians: the Austrian symphonic composer Anton Bruckner, the conductor Wilhelm Furtwängler, the contemporary German-Austrian composer Gottfried von Einem, and the Romantic Franz Schubert. These commemorative plaques are part of the “Vienna Music Mile.” This memorial is quite neglected nowadays and certainly not a worthy “walk of fame” for the music metropolis, but can nonetheless serve as a reminder and orientation guide.

Going By the Ticket and Ball Office…

We cross Bösendorferstraße, bearing the name of the famed Viennese piano manufacturer, and walk down Dumbastraße (named for the Austrian industrialist Nikolaus von Dumba, who was vice president of the Musikverein and board member of the Vienna Men’s Choral Association in the late 19th century), to the Kärntner Ring, where we will turn left.

Philharmonic conductor Hans Richter asks his “dear friend” Ludwig Bösendorfer to tune his pianos.

A few meters on from there we reach the Ticket and Ball Office of the Vienna Philharmonic, in front of which we see more music-stars: for Pierre Boulez, Johann Sebastian Bach and Johann Strauss. The Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra, the only musical organization so represented here, has a star commemorating its first concert on March 28, 1842. As we walk backward through history, we are now approaching this magical date.

Passing stars for Dmitri Shostakovich, Anton von Webern, and Herbert von Karajan (the plaque is graced by the maestro’s signature as well, which Hildegard Knef thought looked like “a cardiogram”), we continue along the Ring to the State Opera building, rising to our right, and which, like the Musikverein, can be considered home base for our orchestra. For since its birth, the Philharmonic has recruited its players from members of the opera orchestra; aside from versatility, this provides economic viability for its musicians. A prerequisite for being accepted into the concert orchestra (organized as an association) is membership in the opera, which has a probationary period of several years. We will come back later to this “double identity” feature of our orchestra. For the moment, let us note that Philharmonic musicians, while playing in the opera, may not be called that, but should sound like it!

…and the other homebase: the State Opera

Only one year older than the Musikverein, the Court Opera Theater on the Ring was completed according to plans of the architects August Sicard von Sicardsburg and Eduard van der Nüll in 1869 and opened on May 25 with Mozart’s Don Giovanni (back then presented in German as Don Juan).

The space to the right of the Vienna State Opera (as seen from the Ring) originally had no name, as it was part of Kärntner Straße. At the instigation of the then director of the State Opera, Ioan Holender, the tract was named Herbert-von-Karajan-Platz in 1996. On the one hand, honoring the outstanding conductor and eminent house director (from 1956 to 1964) is quite appropriate; on the other hand, it makes one wonder how a half century after the end of the war, a square in the capital of Austria can be dedicated to a prominent former Nazi party member…A research group commissioned in the early 2010’s by the University of Vienna and the city to deal with street names identified the Karajan-Platz as a “case needing further discussion.”

Several more musical celebrities are remembered here with stars: the composers Alban Berg and Richard Strauss and their superb conductors Clemens Krauss and Karl Böhm. Then, lined up together, Giuseppe Verdi, Leonie Rysanek, Hans Knappertsbusch and, last but not least, Gustav Mahler. Directly across from the side entrance of the opera house is the beginning of Mahlerstraße, a name it bore at first only between 1919 and 1938. It mutated under the Nazis to “Meistersingerstraße” until 1945 when the name and remembrance of the Court Opera director were restored.

The Kärntnertor-Theater— today Vienna’s most famous Hotel

Behind the opera runs the Philharmonikerstraße, which was given that name in 1942 to mark the orchestra’s Centennial Jubilee year. Crossing this street we find ourselves in front of the world-famous Hotel Sacher. It got its nickname—“Vienna’s most musical hotel”—not just from the huge number of guests from “next door,” but also due to its precise geographic location: from 1709 to 1870 the “Imperial and Royal Court Opera Theater by the Kärntnertor,” the forerunner of the Opera on the Ring stood in this spot. If we just scan the decades before the founding of the Vienna Philharmonic, the Kärntnertor-Theater premiered performances of, among other things, a Schauspielmusik and a piano concerto of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, operas by Joseph Haydn, Antonio Salieri, Conradin Kreutzer, Carl Maria von Weber and Franz Schubert. Schubert’s song Der Erlkönig was first heard here in 1821, and eight years later, Frédéric Chopin had his Viennese debut as a pianist in this theater.

The most significant moments in the house’s history are associated with the name of Ludwig van Beethoven: the premiere of the final version of Fidelio occurred on May 23, 1814, and that of the Ninth Symphony on May 7, 1824. And both were performed by members of the orchestra that was to become the Vienna Philharmonic. The Viennese public felt such a close connection to this musically important site that when the Hotel Sacher was built on the same place, it was forbidden in writing to have any opera performance there.

We could turn right and go on along the continuation of Philharmonikerstraße (Walfischgasse no. 13 was once “Café Parsifal”, frequented equally by opera cast, staff and audience members) but we shall instead stroll up Kärntner Straße. At the end of the block is Maysedergasse, named for the violin virtuoso Joseph Mayseder, who was both a “Concert and Solo performer” at the Court Opera Theater. He never became a member of the Philharmonic, but nonetheless appeared as a soloist in the orchestra’s first concert. We turn right onto Annagasse, at the start of which we are greeted by a memorial star for Arturo Toscanini. The Italian “maestrissimo” shaped the history of our orchestra for only a few years: his debut in October 1933 marked the start of the guest conductor system at the Philharmonic. In early 1938, the fiercely democratic Italian decided to shun Austria, now joined to the German Reich by the Anschluss, and its top class orchestra.

The Haus der Musik

We saunter down Annagasse (passing by the Ristorante Sole, where artists and the public like to go after opera performances), at the end of which is the Haus der Musik. Here we come excitingly close to the founding moment of the Vienna Philharmonic: the composer and conductor Otto Nicolai lived in this building during his service as Viennese Hofopernkapellmeister (Court Opera conductor). A memorial tablet placed in 1942 (at the hundred year jubilee of his once-in-a-century idea to form a concert ensemble from the opera orchestra) shows Nicolai’s portrait, the dates of his all-too-short life (1810-1849), and the date of the first concert he conducted (March 28, 1842—a date we shall not forget so quickly!) remind us of this music-historical milestone.

The text on the house on Seilerstätte opposite turns out to be much more flowery: the marble tablet commemorates the legendary dancer Fanny Elßler, who was born the same year as Nicolai, but lived until 1884, and whose fame became downright mythical. The inscription: “She was the smiling face of her century, one of those rare masterworks whom the creator weighs in his hands for many ages, before releasing them to life.” The most frequently performed work of the 1823/24 season in the Kärntnertor-Theater was the magical ballet The Fairy and the Knight/Die Fee und der Ritter—and the record-breaking number of performances was due to none other than its star: Fanny Elßler.

Let us enter the Haus der Musik, the former “Palais Erzherzog Carl” in the Seilerstätte. It houses, among other things, the Historical Archive of the Orchestra as well as certain publicly accessible memorabilia from the rich history of the orchestra in the Museum of the Vienna Philharmonic.

On the first floor, we pass by displays devoted to the history of the Vienna State Opera before entering a room containing information on the history of the world-famous New Year’s Day Concerts of the Vienna Philharmonic. To the right we are led into an imaginary concert hall, where visitors can experience the high points of the last New Year’s Concert or the Summer Night Concert of the Philharmonic, on large-screen displays. To the left is the historic Hall of Mirrors. Here there is documentation on concert tours, honors and distinctions, the Vienna Philharmonic Ball and the orchestra’s artistic collaborations with composers such as Johannes Brahms, Anton Bruckner, Gustav Mahler, Richard Strauss, Hans Pfitzner, Franz Schmidt and Alban Berg, using original objects.

One’s eye falls on the batons of numerous prominent orchestra leaders— at first glance, that of Toscanini looks to be as long as the others. But if we recall that the Italian maestro used to use an especially long stick to conduct with, we look a bit closer—and in fact, the stick is broken off. This probably occurred as the result of one of its owner’s legendary fits of rage…

The adjoining Nicolai Room has a special document of Austrian cultural history on display: the decree founding the Vienna Philharmonic (see page 27). It also contains the first photograph of the orchestra (1864) and pictures of Otto Nicolai, the violinists Georg and Joseph Hellmesberger and others. And last but not least, the program of the first Philharmonic concert…you surely remember the date!

1842—What a Year!

We could continue our wanderings onto Singerstraße; the inn “Zum Amor” once stood there, where, according to a romantic account, the founding of the orchestra is said to have occurred; then, around the corner in Grünangergasse, in the editorial room of the Allgemeine MusikZeitung the plan was in fact conceived to form the first professional “sound body” of Vienna to give independent concerts…But now it’s time for a pause. If we put that mythic year of 1842 under a magnifying glass, it shows itself to be a most significant year. Let’s pull out the most important dates:

On March 3rd, the “Scottish” Symphony of Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy had its world premiere in Leipzig’s Gewandhaus and was conducted by the composer. A short week later, on March 9th, Giuseppe Verdi’s first international success, Nabucco, first appeared on stage at the Teatro alla Scala in Milan. Verdi was a fateful figure for Otto Nicolai in two senses: for one, the latter had rejected the (in his opinion) inferior Nabucco libretto (“endless raging, blood-letting, screaming, beating and murdering is no subject for me”) and in so doing opened up a pathway for the younger Italian to world fame. And for another, Nicolai’s greatest opera success, The Merry Wives of Windsor, was outmatched more than 40 years later by Verdi’s masterpiece on the same subject, Falstaff, and—unjustly—eclipsed by it. It is no surprise to us that Nicolai could simply not abide the Italian’s music: “He orchestrates like a fool […he] must have a heart like a donkey’s, and is truly in my eyes a pitiful, contemptible composer.”

The scarcely thirty-year-old Verdi visited Vienna in April of 1843 and conducted his Nabucco at the Kärntnertor-Theater—and thus with the musicians of the Philharmonic Orchestra. They had already performed the world premiere of Gaetano Donizetti’s Linda di Chamounix on May 19, 1842. It is noteworthy that the “Rossini-Craze” of the early 20’s, that is, the rage for the composer of the Barber of Seville, was “reignited” two decades later with Donizetti. Back then, German opera played second fiddle in Vienna, even though its greatest master was already standing at the door: Richard Wagner’s Rienzi was produced on October 20, 1842, at the Royal Court Theater of Dresden. It was not to have its first Austrian performance until May 30, 1871, in the “new” house on the Ring. Other new works of note in the year 1842: Michail Glinka’s Ruslan and Ludmilla (December 9 in Saint Petersburg) and finally, on the last day of the year, Albert Lortzing’s Der Wildschütz at the Stadttheater in Leipzig.

Arrigo Boito, the Italian composer and librettist (of Verdi’s last operas, Otello and Falstaff, among others) was born on February 24 of 1842, the operetta composers Carl Millöcker, Arthur Sullivan and Carl Zeller on April 29th, May 13th and June 19th. Our orchestra had hardly any contact at all with the latter-mentioned composers; more, though, with the works of the Frenchman Jules Massenet, who was born on May 12th: his opera Werther had its world premiere in the Vienna Court Opera in 1892.

The birthday of a sister institution should be mentioned, which falls on the 2nd of April 1842: the “Philharmonic Symphony Society of New York” was founded on that day, thus making the New York Philharmonic just a few days younger than the one in Vienna and the oldest symphony orchestra of the USA. Two death dates will round out this musical review of 1842: Mozart’s widow Constanze passed away on March 6 in Salzburg (a mere 51 years after her husband!) and the then celebrated composer Luigi Cherubini died on March 15th in Paris. When the Vienna Philharmonic, then still known as “Orchestral Personnel of the Imperial and Royal Court Opera Theater”, gave its first concert, it included two pieces by the late composer in its program.

In the Nicolai Room of the Haus der Musik, we are in fact physically close to the founding of the Philharmonic, and we can hardly believe that at one time other “founding” dates were being talked about besides this year of 1842…but more of that in the next chapter.

Our ramble through Vienna from the Musikverein to the Haus der Musik

As a token of gratitude for the first Philharmonic concert, the orchestra presented Otto Nicolai with a portrait of himself (lithograph by Josef Kriehuber).

Old and New Home

Founding and Establishing the Orchestra (1842-1870)

After our tour of present-day Vienna, we will now journey into the history of our orchestra to discover more than one anticipation of the present. Today, it is almost impossible to imagine that in the first third of the 19th century, no professional orchestra existed in Vienna. Even Ludwig van Beethoven had to resort to amateur organizations for the performance of his symphonies.

The First “Ninth” and the “Künstler-Verein”

In many respects, the premiere of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony in May 1824 was the first signal flare of the Philharmonic idea. It took place in the Kärntnertor-Theater and was played by the house musicians, augmented by the Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde orchestra. We are reminded of the famous saying by Alexander Wunderer, the oboist and Board Chair of the Philharmonic: “We are the heirs of those who were taught by Beethoven.” The event required two musical leaders, along with Beethoven himself, who by that time was completely deaf. It suffered from the fact that, as demanding a work as it was, it was allowed only two rehearsals with full orchestra and chorus.

The first attempt to found a professional concert orchestra in Vienna dates back to Franz Lachner. Like Otto Nicolai, who successfully founded a lasting institution nine years later, Lachner was a composer and leader of the opera orchestra. The “Künstler-Verein,” or Society of Artists, which Lachner called into being from members of the opera orchestra, gave four subscription concerts in January 1833—however, due to faulty preparation, the undertaking was an economic failure.

“Kreuzdonnerwetter—Schwerenoth! Aufgewacht!”

Nicolai was the first to breathe life into the idea of a professional concert orchestra, with an energy and visionary pertinacity that could take on quite dictatorial traits. We have no record of the first orchestra meeting, but, miraculously, we do have the “Founders’ Decree” from Nicolai’s pen. It begins like a written, but very revved up, carnival manifesto: “Trin tin tin! Hark! Hark! The time has come, no more for musicians just to sleep, or play their violins in bed! Ye sons of Apollo, all together, unite, put your hands to work, on something great! Kreuzdonnerwetter—Schwerenoth! Aufgewacht!” (approximation: Hell and Damnation! Emergency! Wake Up!)

Then Nicolai gets to the point: “All Orchestra personnel of the Imperial and Royal Court Opera Theater and the Kärntnerthor-Theater, led by its good director Mr. Georg Hellmesberger, have united to give a concert under Kapellmeister N[icolai]’s direction, which will be unmatched in the annals of Viennese concerts.” After a short program sketch comes this self-confident concluding paragraph: “Bravo Nicolai! And may the public encourage you in this endeavor, so that from this seed perhaps a beautiful tree will bloom!”

A Prussian from Königsberg, Nicolai had become Kapellmeister at the k. k. Hofoperntheater for a second time (after a brief intermezzo in 1837/38) in 1841. He celebrated his “comeback” in May of 1841 with a highly acclaimed production of his opera Il Templario. (This operatic rarity was recalled and earned enthusiastic reviews in the Salzburg Summer Festival in 2016.) His contract called for him to produce a new opera in Vienna, but it did not happen. The self-confident, all-giving, but all-demanding artist left the city in 1847 following a disagreement with management and the orchestra. Nicolai conducted the premiere of his Merry Wives of Windsor in Berlin on March 9, 1849, and died there two months later. For this native Prussian, Vienna could not be replaced by anything, as he confided to his diary: “Berlin probably has more order, which I missed so dearly in Vienna—but the Viennese has more music in his blood […] The south just has more talent!”

The “Founding Decree” in Otto Nicolai’s hand

The Triad of Founders…

…of the Philharmonic, besides Nicolai, consisted of the Viennese writer and journalist August Schmidt (1808-1891) and the Manchester-born German Alfred Julius Becher (1803-1848). Schmidt was, among other things, a co-founder of the Allgemeine Wiener Musik-Zeitung (1841), of the Wiener Männergesang-Verein