Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Batsford

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

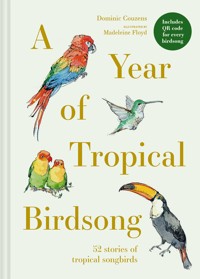

Fascinating stories of the birds and birdsong from the Tropics for every week of the year, with QR codes to bring the birdsong to life. From the incredible screech of the macaw, who shows amazing intelligence, to the imitations of humans of the mynah bird and the humming sounds of the hummingbird, this is a beautiful collection of stories about one of nature's wonders: tropical birds. Bird expert and writer Dominic Couzens invites you to enjoy not only their songs but also their amazing feats and colourful displays. With stunning illustrations from award-winning Madeleine Floyd and QR codes to listen to their songs as you read, you can immerse yourself in a tropical wonderland. A natural wonder that has captivated and fascinated generations, tropical birdsong is unique. This book offers the perfect tonic, whether you are an avid birdwatcher or just want to understand the songs from the most iconic birds in the world. With 52 weekly stories, the book takes you through the calendar year of tropical life. Listen and read about jewel-like toucans, mating cries of the cock-of-the-rock bird of paradise, duet songs of sunbirds, the fascinating glossy starling oxpeckers who sit on the backs of elephants and the gorgeous songs of hornbills. The latest research and information about these bright lights of the bird world is captured here by one of the most respected but accessible writers on birds. It's like joining him on a field trip. Anyone interested in birds and nature will be captivated by these stories and sounds.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 189

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Contents

WEEK 1 Galápagos penguin

WEEK 2 Ocellated antbird

WEEK 3 Purple-crested turaco

WEEK 4 Fiery-throated hummingbird

WEEK 5 Lesser flamingo

WEEK 6 Pink pigeon

WEEK 7 Blue-and-yellow macaw

WEEK 8 King of Saxony bird-of-paradise

WEEK 9 Red-capped manakin

WEEK 10 Resplendent quetzal

WEEK 11 Superb starling

WEEK 12 Screaming piha

WEEK 13 Black-faced solitaire

WEEK 14 Brown wood-owl

WEEK 15 Fire-tailed sunbird

WEEK 16 Northern carmine bee-eater

WEEK 17 Purple-crowned fairywren

WEEK 18 Red-billed oxpecker

WEEK 19 Oilbird

WEEK 20 Indian cuckoo

WEEK 21 Eastern paradise-whydah

WEEK 22 Blue whistling-thrush

WEEK 23 Hooded pitohui

WEEK 24 Asian koel

WEEK 25 Malayan banded pitta

WEEK 26 Bluish-fronted jacamar

WEEK 27 Indian peafowl

WEEK 28 Dark-necked tailorbird

WEEK 29 Black-naped oriole

WEEK 30 House crow

WEEK 31 Red-headed lovebird

WEEK 32 ‘I‘iwi

WEEK 33 Sparkling violetear

WEEK 34 Yellow-crowned gonolek

WEEK 35 Golden bowerbird

WEEK 36 Bay wren

WEEK 37 Rhinoceros hornbill

WEEK 38 Red-cheeked cordonbleu

WEEK 39 Andean cock-of-the-rock

WEEK 40 Common hill myna

WEEK 41 Yellow-vented bulbul

WEEK 42 Greater bird-of-paradise

WEEK 43 Village weaver

WEEK 44 Jungle babbler

WEEK 45 White-browed robin-chat

WEEK 46 Toco toucan

WEEK 47 Wompoo fruit-dove

WEEK 48 Common potoo

WEEK 49 Buff-breasted paradise kingfisher

WEEK 50 Harpy eagle

WEEK 51 Grey parrot

WEEK 52 Tinkling cisticola

Introduction

WELCOME TO THE WORLD OF TROPICAL BIRDS AND their songs.

You might well have an idea of what a ‘tropical’ bird sounds like in your imagination. Perhaps it’s a squawk, or a chatter, or something more melodious. In this book you have the sounds at your fingertips, on the page and through the QR codes.

This book introduces 52 tropical species, one for every week of the year. Bird song in the tropics is different to temperate bird song, in that it is much less seasonal, in line with the tropical environment, which lacks the defined winter, spring, summer and autumn (fall) further north or south. Many of the species found in this book vocalize all year round. However, I have tried to choose suitable weeks for each species, tending to choose its peak singing season, if it has one, which is often during the rains.

Hopefully, all your tropical favourites are here. On these pages, you will meet parrots, hummingbirds, toucans, birds-of-paradise, sunbirds, quetzals and many others. Many are dazzling in colouration and the rest are dazzling in their amazing lifestyles, which are often extreme and sometimes strange. Within these pages the QR codes will allow you to hear everything from a macaw’s screech to the ethereal loveliness of the black-faced solitaire. Hopefully, a combination of astonishing lifestyle and curious sounds will keep you entertained!

For clarity, it seems sensible to define the tropics and the birds therein. The tropics is the zone between the Tropic of Cancer at about 23°N and the Tropic of Capricorn at 23°S, which encompasses the Equator in the middle at 0° latitude. The zone includes both land and oceans, and accounts for about 40 per cent of the Earth’s land surface. For the purposes of this book, any bird that breeds in the tropics is valid for inclusion.

Most people are aware that the tropical zone holds a greater degree of biodiversity than the rest of the planet; about 75 per cent of all the world’s species, be they birds, plants, mammals or anything else, are squeezed into its area. As a general rule, this biodiversity reaches its peak nearest the Equator. Thus, you find astonishing disparities between places – a few hectares of equatorial South American forest may hold as many breeding species of birds as the whole of the North American continent, for example. To tread in these forests is to be nestled in the cradle of biodiversity, and it is an astonishing experience.

Intriguingly, there is no complete agreement as to why this area is so species rich, but there are two main hypotheses. One is that tropical regions are simply hotter, wetter and have high productivity and energy in the system; they lack the climatic extremes of north and south, so more species evolve and those that are there are able to survive for longer. The second hypothesis is that there has been more isolation and fragmentation in tropical regions over geological time, for multiple reasons, driving the divergence between species, and this has fostered the extraordinary biodiversity. Whatever the reason, recent studies have found that tropical birds, compared to their northern or southern counterparts, exhibit a wider genetic variation within species, and this variation is more persistent between generations.

There are four main tropical regions with different bird faunas. The New World tropics (neotropics) cover Central and South America and is the richest zone in terms of species; the Afro-tropics cover the African continent; the Asian tropics include much of south-east Asia and nearby islands, but the large island of New Guinea and continental land mass of Australia, plus the various islands of Oceania, is a separate region ornithologically, the Australo-Papuan tropics. For this book, I have chosen about the same number of species from each region.

There are some intriguing differences between temperate and tropical birds, not all of which are understood. One difference that has long been assumed as fact by most people, although based on anecdotal evidence, is that tropical birds are more colourful than the rest. Only recently has this been confirmed by mathematical colour analysis. It found that tropical birds were 30 per cent more colourful than the rest, especially in bright blues and greens, and that the colours were both more varied and more intense. Again, this is likely to be related to the overall energy and resource richness of the tropical ecosystems. If food is more readily available, a bird has more opportunity to put energy into evolving bright colours.

This also works for some of the elaborate displays and breeding behaviour exhibited by tropical birds. It has long been postulated that a diet of fruit, which can be found all year round and requires rather less time to satisfy a bird’s daily feeding requirements, has emancipated some male birds from the daily foraging grind and enabled them to evolve sexual ornaments and display routines of quite marvellous splendour. The manakins (see here), cotingas (see here) and birds-of-paradise (see here and here) are all good examples of this, providing the watcher with some of the most exciting wildlife viewing of any on the planet – and usually with a remarkable soundtrack, too. Some individuals may display every day of the year. When displaying against other males, in a communal display called a lek, they are easily compared and contrasted by visiting females, saving the latter the trouble of comparing widely-spaced individuals.

Another breeding system often adopted by tropical birds is group living. Also seen in birds of arid zones, it involves extended families contributing to a communal breeding attempt. One of the factors that enables this to occur is that, at least among songbirds, individuals live longer in the tropics. That means that a young bird can spend a season helping its parents with a new breeding attempt, ‘assuming’ it will live long enough eventually to graduate to a breeding attempt of its own in future years. Several species in this book, including the purple-crowned fairywren (see here), jungle babbler (here) and superb starling (here) follow this type of lifestyle.

There are several other interesting differences in tropical bird biology, and these are still being studied in an attempt to explain them. For example, temperate birds lay consistently larger clutches of eggs: in an analysis of 5,000 species, tropical birds laid two eggs on average and temperate birds 4.5 eggs. However, in another study, it seems that tropical birds try more clutches per year. In yet another study, it was discovered that tropical songbirds grow their wings more quickly than temperate birds, meaning that they fly well when they fledge. It is thought that, with such diversity in the forests generally, there are more potential predators, so learning to fly as soon as possible is a good survival strategy. The upshot, though, is that tropical parents feed their chicks for longer than temperate birds, because the chicks’ overall weight increases more slowly in the tropics.

And, of course, songs and other vocalisations also show differences. As mentioned above, one is that tropical bird songs are much less seasonal. Singing effort may increase prior to and during the rains, when a bird is preparing for breeding, but it many cases it continues all year round.

A reminder is in order here that there is a broad distinction used everywhere between bird SONGS and bird CALLS. SONGS are the typically complex vocalisations that birds use to make a point – perhaps defend a territory or attract a mate, or both. Songs also stimulate birds’ brains to release hormones associated with breeding, and typically help a male and female to be synchronized physiologically. CALLS are simpler vocalisations, often just a single note or two, that are used in multiple situations, such as contact or alarm. In the tropics, members of mixed parties tend just to give calls to keep together. Call notes may not be associated directly with breeding, but songs always are.

That said, one very significant difference between the tropics and temperate zones is that female song is much more significant and frequent in the former. There are a small number of species in which females sing more than males (such as the streak-backed oriole of Central America and Mexico in parts of its range) and, since this is an area where research is quite intensive, there will no doubt be many more discovered. But generally speaking, it is very common in the tropics for females to sing loudly and frequently, whereas it is unusual in temperate areas.

There are probably several reasons for this. In the tropics, songbirds live longer and often form long-lasting, stable pair bonds. In this situation, it makes sense that both would contribute to the usual role of song, which is to defend a territory from other birds or pairs. At the same time, in places where seasons are less well-defined and there are fewer cues to begin breeding, if both members of a pair sing they can mutually stimulate each other and prepare in synchrony for breeding.

Related to this is another typically tropical phenomenon, duetting. It isn’t exclusive to the tropics, but it is much more common in this region. It is found in about 200 species worldwide, including the bay wren (see here) and the yellow-crowned gonolek (see here), and will probably be found in many more. Duetting involves the male and female singing at the same time. Sometimes they will simply alternate their contributions (antiphonal duets) but at other times they will integrate in a far more complex and intricate manner – it can be all but impossible, listening, to tell that it is two birds, not one bird, vocalizing. Duets are associated with birds that have long term monogamous pair bonds, and in its simplest form a duet can enable a member of the pair to know that its partner is nearby. Duets can also be aimed at neighbouring pairs and competitors, ensuring that territories and pair bonds are preserved.

This book, therefore, is a celebration of all things to do with tropical birds, from their bright colours to their unusual and complex lifestyles. The soundtrack is as varied as the birds themselves. Hopefully, you will find and hear something that you find inspiring and amazing.

As ever, with any such book, there is a sadness in writing it. No reader will be unaware that tropical birds all around the world face large population declines in line with their shrinking habitat. This book is a reminder that the world is an astonishing place and the wildlife within it has the capacity to thrill us and make our lives immeasurably better. Everything, from the birds themselves to the sounds that they make, is worth preserving.

Dominic CouzensUK, September 2024

WEEK 1

Galápagos penguin

Spheniscus mendiculus

GALÁPAGOS ISLANDS, OFF WESTERN SOUTH AMERICA48–53cm (19–21in)

THERE WILL BE PLENTY OF TROPICAL favourites featured in this book, but let’s begin with a penguin. After all, what bird would you least expect to find among the parrots and hummingbirds on these pages? Perhaps one that is supposed to live with a backdrop of icebergs? Yet here it is, completely worth its place, a bird that doesn’t just live in a very hot climate but occurs right on the Equator, the very heart of the tropics. And, whisper it quietly, it also lives permanently in the Northern Hemisphere, which penguins ‘are not supposed to do’.

The Galápagos penguin is still an outlier and owes its existence to the cold-water currents of the Pacific Ocean, two of which, the Humboldt and Cromwell currents, flow as far north as the Galápagos Islands. Despite all the photos you have seen, what penguins really need is not cold land but cold water. Some of the world’s most productive oceans, where turbulence is the norm and nutrients are swept violently up towards the water surface, are found in the seas and oceans around Antarctica. But cold currents can also flow north. The waters off the Galápagos are unusually cold and unusually productive, hence the anomaly. Not too far to the south, another penguin, the Humboldt penguin (S. humboldti), lives on the coast of Peru. Both are very small species.

In these curious surroundings, penguins still do penguin things. The Galápagos penguin spends much of its time in the water chasing fish, in this case usually no more than 60m (200ft) from the shore. It relies on large shoals of small species such as anchovies, mullet and sardines. It tends to dive below a shoal and snatch them as it heads for the surface. Although we typically think of penguins as fast swimmers, they don’t reach speeds more than 2m (6½ft) per second when hunting. At night it roosts on land but spends almost all its day in the water.

For breeding, these penguins don’t have very much choice, so they use crevices in the volcanic rocks of the islands where they breed (Fernandina, Isabela). Where there is loose soil, they will dig a burrow. This species breeds twice a year, with a peak in egg laying at this time of year (December to March) and another between June and September, quite a contrast to the larger penguins, which might raise one chick every one and a half years. The normal clutch is two, and the youngsters hatch anywhere between two and four days apart, which usually favours the older nestling. The pair bond is exceptionally stable in this species; 93 per cent of all adults remain together between one year and the next. Divorce is a pretty risky process when your entire population is only 2000 birds.

Galápagos penguins are always vulnerable to the vagaries of the cold currents that are their lifeblood. Whenever the local waters heat up to 25°C (77°F), the populations of fish plummet and breeding success crashes. Every time there is an El Niño event, the cold current is reduced in strength and the penguins either try to breed and quickly fail, or they don’t try to breed at all. Unfortunately, these events are becoming increasingly common, with the seas being too warm too often. This delightful penguin is already listed as Endangered on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species, and its future is in very real peril.

For now, though, the Galápagos penguin continues to defy our perceptions of its family, and here’s an astonishing thought. On the Galápagos Islands, penguins may incubate their eggs in extreme heat, sometimes as high as 40°C (104°F). Contrast this with their relatives in the same family, the Emperor penguins (Aptenodytes forsteri), which incubate eggs on their feet at ambient Antarctic temperatures of -40°C (-40°F). That’s a remarkable range within a single bird family.

The Galápagos penguin spends much of its time in the water chasing fish, in this case usually no more than 60m (200ft) from the shore.

WEEK 2

Ocellated antbird

Phaenostictus mcleannani

CENTRAL AND NORTHERN SOUTH AMERICA17–20cm (6¾–8in)

IT’S DAYBREAK IN A LOWLAND RAINFOREST in Central America. Out of the darkness comes a loud, accelerating, then decelerating whistle, vaguely recalling a blast from a sports referee. This is the song of the ocellated antbird, and it’s a bird in a hurry. It’s the antbirds’ rush hour.

Trying to locate an ocellated antbird in the morning gloaming can be a fool’s game. You might hear one close by and peer into the understorey hopefully, but the chances are that it will move on rapidly before you spot it. The next song may be from around a corner on the forest trail, then the next a little further away. This is because, unlike most birds singing in the forest at dawn, this one is on the move.

The reason for the antbird’s skittish daybreak behaviour is that it is searching for the right place to begin its foraging for the day. It’s not looking for a glade of sunlight or a fruiting tree, but something much more unusual. It is searching for a moving column of soldier ants (Eciton spp.).

The primary rainforests of the neotropics play host to huge colonies of these formidable insects. These are the ones that sweep across the forest floor, catching and killing every invertebrate (or small vertebrate) in their path. In a raid lasting a day, 200,000 marching ants may kill up to 100,000 other animals; the next day is the same. At night the ants make bivouacs out of their own bodies, fitted together using hooks on their feet. But at daybreak, the rivers of ants flow out once again and may be 100m (330ft) long.

It is these columns that the ocellated antbird is seeking. You might quickly assume that the ants themselves are nourishment for the birds, but this isn’t the case. Instead, the birds station themselves at the margins of the columns, particularly at the front, because what they are after are the invertebrates fleeing the ants. Knowing that doom awaits them if they stay still, many thousands of insects, spiders and others flee for their lives; it is at this moment of vulnerability that the antbirds strike. It might be a kinder death. Most animals that the ocellated antbird eats are smaller than 25mm (1in) in length.

The ocellated antbird is unusual for being what is known as an obligate ant-follower: it spends its entire life following ants and never feeds anywhere else.

Effectively, then, the antbirds are cashing in on the ants’ raids, and they aren’t the only ones. Within these superabundant forests there is a whole guild of species that do the same thing; these aren’t just antbirds, but birds from many other families as well. At the swarm there is a hierarchy. The ocellated antbird, being larger than most, is dominant, and often forces other birds away from the best perches at the head of the ant column. The ant followers often stay around 2m (6½ft) above ground, and are especially adept at clinging on to vertical stems.

Within the ant-following guild, there are differing levels of dedication. Some species come and go, alternating the odd bout of ant-following with other, more conventional types of foraging. Some species are only occasional followers. But the ocellated antbird is unusual for being what is known as an obligate ant-follower: it spends its entire life following ants and never feeds anywhere else. Even when attending its nest during breeding, it still visits the ant columns. Only in the stable and extraordinarily rich and diverse habitat of a tropical forest could such specialization occur.

Ocellated antbirds have quite large territories of about 50ha (124 acres). Within this territory, multiple ant colonies occur and a given pair will visit a number of these each day. Their most important appointment, though, is in the early morning, and the first meal of the day.

WEEK 3

Purple-crested turaco

Gallirex porphyreolophus

SOUTHERN EAST AFRICA42–46cm (16½–18in)

TURACOS ARE THE PUBLIC ADDRESS systems of African forests. Every daybreak, groups of these birds announce the dawn with loud barking calls. When one group proclaims from the dimly lit treetops, the neighbouring group is stimulated to do the same, and so their crowing resonates through the district as everyone awakes. Local legend has it that turacos call on the hour, every hour, and nearby farmers can time their activities accordingly. There are more melodic birds that welcome the African dawn, but the turacos are the loudest. It is almost as if they have heard about the famous sound of that other herald of the dawn – the cockerel – and this is their attempt to emulate it.

The purple-crested turaco, found in evergreen and riverine forests in the south-east segment of tropical Africa, has one of the more elaborate reveilles among its small family of 24 species, often emitting 10–15 or more grating calls in sequence. In common with many members of the family, hearing it is a lot easier than catching a glimpse. Turacos are the very definition of an arboreal bird, spending almost all their time in the forest canopy and this means that, despite their size, they can be difficult to spot. The best time is when a pair or group decide to move trees; they tend to do this in single file, each bird flapping at treetop height, slightly unsteadily, the long tail trailing behind.

For many centuries, turaco feathers have been much prized and placed in head-dresses.

The feet of turacos are unusual. They have four toes, two facing forward and two back, but one of the back toes can rotate almost 70 degrees, allowing remarkable flexibility when the bird is in the tree canopy, where it may need to run along branches or hang in awkward positions. Turacos are more agile in the trees than they are in the air.

What they are seeking in the forest canopy is fruit, their exclusive diet. In common with many tropical birds, they are particularly fond of figs, but they eat a very wide range and have been recorded eating 134g (4¾ oz) of food in a day. Most of the fruits are swallowed whole.