25,19 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Batsford

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

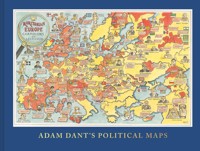

A timely, large-format collection of fine art maps from Adam Dant, looking at the fractious world of politics. Adam Dant's Political Maps is an all-new collection of this highly regarded artist's intricate, absorbing and beautiful maps, this time focused on the world of politics. Informed by his experiences as the official artist of the UK general election in 2015, these glorious works of art are amusing and subversive, hugely imaginative and packed with eye-catching detail. Themes range across the spectrum of British and global politics past and present, bringing in recent political upheavals ('Stop That Brexit') and current issues such as the controversy around certain statues ('Iconoclastic London'), alongside more timeless subjects like a map of US presidents ('Presidents of the United States of America'), and, of course, the pandemic ('Viral London'). Other highlights include: - Johnson's London: Notorious places associated with Prime Minister Boris Johnson, including all the houses he has ever lived in - New York Tawk: A visualisation of New York City through a century of its slang - British Left Groups: A fascinating history of left-wing parties and pressure groups through the decades - Quitting Europe: Brexit encapsulated in exotic European cigarette packets from the artist's youth Witty, acerbic and intelligent, this unique collection will delight history enthusiasts, art lovers and politics buffs of all persuasions, and its large format guarantees hours of happy browsing of the densely packed detail Adam Dant brings to all his images.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 158

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

CONTENTS

Introduction

Division

The Mother of Parliaments

The Government Stable

Johnson’s London

The Ministry + Passion of J.C

British Left Groups

Stop That Brexit

Ruritanian Europe

The Invasions of the British Isles

Quitting Europe: Some Anecdotes

Rudimentary London

The London Rebus

Viral London

Iconoclastic London

The London Calendar

The Universal London Underground Map

The Critic’s Perpetual Drinking Calendar

Jewish Spitalfields

Club Row Through the Ages

Guardians of London’s Lost Rivers

Civil War Defences

Argonautica Londinensi

Triumph of Debt, Royal Exchange Square

Triumph of Debt, Canary Wharf

Moneyscrape

Prime Ministers of the United Kingdom

Presidents of the United States of America

Cockney Rhyming America

New York Tawk

Paris Argot

The Oxford Meridian

Metaphysical Cambridge

Theatreland

A Map of the National Gallery: London’s Collection of Subliminal Images

Tulip Fever

Coco-opolis

Scottish London

A Walk Round the End of the World

Lindon: A Map of London as it Might Have Been

The Mind of East London

The Gentle Author’s Tour of Spitalfields

The Paradise of Sleaze

The Great British Beast Chase

The Meeting of the Old & the New East End in Redchurch St

Operation Owl Club

An Encyclopedy of Ye Age of Enlightenment Citizens & Kings

Stanfords World of Covent Garden

Acknowledgements and Credits

THE ART OF POLITICS AND THE POLITICS OF ART: MY LIFE AS A ‘POLITICAL ARTIST’

When artists apply the qualification ‘political’ to describe themselves and their practice it rarely means that they are involved in conventional politics.

Typically the ‘political map’ as opposed to a ‘physical map’ is a map that shows territorial borders, and though the maps illustrated and described within the pages of Adam Dant’s Political Maps do not for the most part describe the world according to its borders, their engagement with ‘the political’ as a facet of the everyday life of ‘the electorate’ worldwide can be deemed ‘political’ enough for the Chinese Communist Party to discourage all the printers of their nation from printing such a book.

Within this particular ‘atlas’ the parameters of what constitutes a ‘political map’ are stretched as wide as possible so as to include such diverse subjects as ‘A Global History of Chocolate’, ‘The Metaphysical Life of the Sculptures at the Seats of Learning in Cambridge’ and ‘The Gutter Language of the Parisian’, as well as the more obviously political themes of ‘US Presidents’, ‘British Left Groups’ and – for the reader who just happens to also be a serving UK politician – a handy map showing the locations of all the ‘Division Bells’ in Westminster.

Maps as a tool most famously manipulated by leaders, politicians and the occasional despot have provided us with the current widespread and slightly hackneyed Magritte-style view that ‘the map is not the territory’. In the way that the political maps within this tome have been wrangled and wrought to serve all manner of unusual functions, such as in the creation of a ‘Cockney Rhyming Slang’ glossary of the United States of America, there is barely even a slim possibility of their being taken as depictions of reality.

Rather than existing as vehicles for polemic, proselytizing, pamphleteering or even as mere entertainment, these political maps append the cartographic milieu to an aesthetic and intellectual exercise, creating an armature on which to hang anecdotes, taxonomies, facts and factoids as part of various vaguely philosophical enquiries into the nature of systems, methodologies, social practices and the cataloguing of such seemingly random phenomena into lucid visual histories. Or, to put it more succinctly, in the words of Alan Sillitoe’s character Arthur Seaton: ‘All I’m out for is a good time … all the rest is propaganda.’

Each map in this volume thus embodies the word ‘politics’ according to its former meaning, being something for public benefit, at the same time as incorporating the kind of manipulative process for which the word more commonly stands today.

My own engagement as a fine artist with the world of conventional politics really opened up when I was appointed by the Speaker’s Committee for Works of Art as the UK Parliament’s Official Artist of the General Election 2015. The commission took me the length and breadth of the UK on a tour that involved sketching all manner of campaign events in preparation for the creation of a huge drawing to represent the UK electorate’s engagement with the democratic process.

Thus, although the resulting work of art, ‘The Government Stable’, can be described as a ‘political map’ of sorts, the political is very much enmeshed in the fairly mundane quotidian world that candidates strive via their manifesto promises to understand, fix and improve. The whole complex work of art is underpinned by a hidden cartographic matrix of the UK’s geography and was constructed around the quintessential object of electioneering during the 2015 campaign, namely the ‘Ed Stone’.

The Ed Stone, for those who need reminding of the most bizarre highlight of the 2015 general election, was a massive granite monolith inscribed with manifesto pledges that the former Labour leader Ed Miliband had promised to install as a hefty garden ornament at Number 10 had the British people chosen him as their prime minister.

During the 2015 general election campaign the Ed Stone was just one of numerous weird electioneering curios that found their way (hidden in a packing crate in the case of the Ed Stone) into ‘The Government Stable’.

A key is provided with the image to allow for the identification of all these objects, as even the most crazed politics geek would have trouble recalling the decorative screen that served as a backdrop for the display of Indian cooking in a Cardiff Balti House by Nick Clegg (then leader of the Liberal Democrats). The unfortunate incident of Ed Miliband and the bacon sarnie, when he’d been caught on camera the previous year awkwardly eating his breakfast at a New Covent Garden Market caff, had led to party press officers asking tabloid photographers to lay down their cameras at lunchtime. A polite but firm Lib Dem lady with a clipboard requested that I too put down my sketchbook while her leader had his curry. I remonstrated that my crayon renderings were not quite in the same milieu as the work of the paparazzi, but she insisted that they were the same thing. ‘What if I draw the scene from my imagination on the train home,’ I asked. She gave me a stern, humourless look and told me that her team would prefer – and indeed would recommend – that I didn’t.

For the most part the various parties’ political advisors and fixers of 2015 were charming, helpful and very smart. Things only got tense during unfortunate off-message moments, inevitable cock-ups and perceived biased-media stitch-ups. Until I pointed it out in a sketch, nobody had noticed that the sleeves of the Conservative leader David Cameron’s white shirt, which he always wore rolled up ready for the hard job at hand, had actually been steam-ironed thus by one of his loyal and fastidious aides. The SNP’s press officer told me he was ‘very disappointed’ with my illustrated artist’s diary entry from a huge anti-Trident rally in Glasgow. When I asked why, he told me that he’d been there with his kids and he hadn’t heard any of the crowd shouting to the press pen, ‘If any of you are from the BBC we’ll come down to London and burn down your houses,’ as I’d recorded.

The campaign trail of 2015 was a very friendly one and despite it being the first ‘Twitter election’ that particular social-media conduit had yet to become the cesspit of hostile opinion and spats that it is today. As a guest and in-house artist on ITN’s big election-night broadcast I was even given a biscuit decorated with a blue iced Twitter bird by the company’s political pundit. That things change so quickly in the world of politics – the faces, the events, the decisions all so fleeting – for the artist presents a subject that offers both an opportunity to be part of something that seems important and monumental at the time, while also embodying all the transient and, in terms of aesthetically compelling material, a series of extremely mundane-looking elements that attend the creation of legislation.

The current Atelier Dant.

DIVISION

When I was a child, in common with many other young people at the time, I wrote a letter to my local MP asking if they would give me and my classmates a tour of Parliament. My MP wrote back straight away and very soon a bunch of raggedy nine-year-olds were stuffed into the St Laurence’s Catholic Primary School’s rusty old school minibus and driven from Robert Rhodes James’s seat in Cambridge to the seat of power in Westminster.

What I remember in particular from our tour of the upper and lower chambers of Parliament with its dark, scary, wood-panelled, bookcase-lined Victorian corridors was Mr Rhodes James’s description of his home in the capital. Did he come here from Cambridge every day? I’d asked. When he informed us that he also had a home in London ‘within the division bell’ my stupid nine-year-old imagination (and I was not alone in thinking this) immediately imagined our MP having his living quarters inside an actual bell. One of the nuns had been reading to us from James and the Giant Peach that term. If a seven-year-old boy could live in a big piece of fruit then why couldn’t a politician live in a big bell? It’s a good idea.

Once I’d finished drawing this map, which locates several of Westminster’s ‘off-site’ division bells, I realized that in effect our MPs do all live within a big bell.

As well as the bells that sound within the Parliamentary estate to call MPs back to the chamber to walk through the division lobbies whenever there’s a vote, there also exists a whole network of extramural tintinnabulary tips to make sure members know that if they don’t get back to the Central Lobby within eight minutes then they’ll be ‘locked out’ and miss a vote. When the Houses of Parliament were rebuilt after the destructive fire of 1834, the provision of victuals was not as copious as today, necessitating lunches at the pubs and kitchens of the general environs. The unofficial famous last words of Pitt the Younger were not the prosaic ‘Oh, my country, my country,‘ but ‘I could eat one of Bellamy’s veal pies,’ Bellamy being the chef to the Parliamentary estate.

In creating ‘Division: Who Goes Where in Westminster’, stories of political ‘gourmandizing’ are rife. Every venue that has a bell, from the St Stephen’s Tavern to the Cinnamon Club, has a colourful tale to tell. The general operation of this system in its off-site incarnation (with 172 locations, according to Wikipedia) is a mystery worthy of investigation by the legendary ‘double-0’ denizens of the St Ermin’s Hotel, whose doormen proudly point out their own recently restored (but possibly ‘disconnected’) division bell to all visitors.

There’s a lot of work that can be done in the pubs and restaurants of Westminster secure in the knowledge that votes will not be missed thanks to this arcane system of wires, circuits and metal cloches. I tried to trace the source of the system but, after being blinded by science and secrets in a basement room behind a door labelled ‘Engineering Control’ directly underneath Parliament’s Central Lobby, I much prefer to stick to the idea that our elected representatives are happily installed and ready for action, owl-like, clustered within a massive bell.

DIVISION

Hand-tinted print56 × 76cm (22 × 30in)

THE MOTHER OF PARLIAMENTS

‘The Mother of Parliaments: Annual Division of Revenue’ is a contemporary almanac that took its inspiration from the state of British politics in 2017 and the political life of Baron Ferdinand de Rothschild (1839–98), Liberal MP for Aylesbury from 1885 to 1898, who built Waddesdon Manor.

This particular almanac is a modern and subversive response to the exhibition ‘Glorious Years: French Calendars from Louis XIV to the Revolution’, which showcased a remarkable – but little-known and never before displayed – collection of calendars (originally named ‘almanacs’). The exhibition charted the evolution of these calendars from their golden period under the reign of Louis XIV to the French Revolution, when time itself was re-invented.

Our modern politicians are re-imagined through the lens of the official almanacs of the Old Regime. The Mother of Parliaments replaces the French kings and their attributes, with the unusual spectacle of the glorification of modern British MPs, their power and reverence communicated through an everyday print.

Almanacs are political documents, issued as propaganda exercises by the French establishment and, later, by those seeking to overthrow it. As a modern reflection of that spirit, it exists as a print for the British electorate of 2017.

Suitable for hanging on the walls of every British kitchen in place of the ubiquitous kitten calendar or stately-home tea towel, ‘The Mother of Parliaments: Annual Division of Revenue’ allows for the division of the annual governmental budget among its various departments to be pencilled in from year to year using blank roundels across the design. The central calendar panel lists the birthdays of the UK Parliament’s 650 MPs in the manner of a liturgical or Jacobin menologion.

Set against a backdrop of the Central Lobby of the Palace of Westminster is a schematic rendering of the important buildings, figures and symbols of government. Familiar political faces such as the then Prime Minister, the Leader of the Opposition and MPs in charge of the Foreign Office, the Home Office and HM Treasury are rendered in the timeless style of classical allegory.

The depiction of each is elevated stylistically in the manner of the 18th-century French almanac model. The drudgery and grey facade of Civil Service life thus acquires something of the triumphant self-aggrandisement of the French Court or the Revolutionary National Assembly.

ALMANAC FOR THE YEAR 1734 (THE AUGUST PORTRAITS OF THE FIRST BORN SONS OF OUR KINGS)

(Unknown, 1733). Etching and engraving on paper, Waddesdon Manor.

THE MOTHER OF PARLIAMENTS

Hand-tinted print with interchangeable calendar56 × 76cm (22 × 30in)

THE GOVERNMENT STABLE

‘The Government Stable’ currently hangs on the mezzanine at Portcullis House, alongside other works of art from the Parliamentary collection: portraits of MPs styled according to reputation, depictions of cabinets long gone and now the subjects of BBC period dramas, and the occasional image of Parliament on fire in 1834.

The two dozen sketchbooks I had filled with ‘lightning’ sketches of campaign events, manifesto launches and voter canvassing from across the length and breadth of the UK, politically as well as geographically, have just been donated to and acquired by the Speaker’s Advisory Committee on Works of Art. In 2001 this parliamentary committee, under its then chair Tony Banks, had created the role of ‘Election Artist’.

Speaking recently to the 2019 Election Artist, the sculptor Nicky Hirst, we both agreed that despite the post being a great privilege for an artist it also had the potential to be a disorientating and nerve-wracking experience fraught with all manner of unfathomable unknowns.

On learning of my own appointment for the 2015 general election there was an expectation from the political candidates, the press and the public that my ‘official Election Artist’ role might be akin to being some kind of cruise-ship cartoonist or even like a ‘War Artist’.

Despite insisting that I was not a caricaturist, John Humphries on the Radio 4 Today programme kept asking me who was the best party leader to draw. In frustration I was on the brink of saying that of all the candidates, with his static oration style and ‘LibDem standard’ looks, Nick Clegg would make the best nude life model. Sadly the Slade’s loss is Facebook’s gain there.

The war artist comparison was closer, though in my admiration for the ‘reportage’-style drawings of Goya, Winslow Homer, Ronald Searle and Linda Kitson I was concerned that a visually dynamic view of an exit poll, for example, or a drawing of Samantha Cameron gloss-painting a park bench might not prove quite as dramatic as the bloody horrors of the Peninsular War.

My initial concerns as to whether an election campaign might provide much in the way of visually interesting material were allayed as soon as I received the first Liberal Democrat Party’s ‘operational notice’ inviting me to a press call at a hedgehog sanctuary.

The campaign trail from one bizarre event to the next continued apace for six weeks. From witnessing the Queen guitarist Brian May handing out enamel prefects’ badges with Caroline Lucas under the Brighton bandstand to the DUP candidates hanging from the back of a London bus, Summer Holiday style, in the midst of a remote field in Northern Ireland, I soon had a nice sketchbook collection of strange campaign tokens and mementos.

It was the attendant objects, props and effects of electioneering that, for me, when separated from the grip of politics, added a more humanizing and poignant aspect to a political process that can by turns appear cloying, tedious, repetitive, desperate and – in the case of the most recent 2019 election campaign – nasty and divisive.

In the end, politicians are entirely absent from ‘The Government Stable’. The closest any of the 2015 contenders come to being depicted is David Cameron, whose disembodied arm, sleeve rolled up (and ironed) is mounted trophy-like on a wall clutching the infamous ‘I’m afraid there is no money!’ note scribbled by Labour’s outgoing Treasury Secretary Liam Byrne in 2010. Nigel Farage is somewhere in there too, but buried deep within a life-size alabaster sculpture of a seething press scrum.

THE GOVERNMENT STABLE

Sepia ink drawing2.74 × 2.13m (9 × 7ft)

PLACES

1. Leeds Town Hall: The Victorian civic architectural splendour of Leeds Town Hall is the venue for the BBC’s final leadership orations. Ed Miliband has a slight Madonna-at-the-Brit-Awards stumble from the stage. The ceiling and arches are decorated with the logos of the UK political parties.

2. Central Methodist Hall, Westminster: The clock and pipe organ are from the hall where the BBC’s ‘Challengers’ Debate’ takes place. The clock marks the time – 10pm – that polling stations across the UK close and voting ends.

3. Swindon University Technical College water tower and courtyard pavement: Venue for the Conservative Party manifesto launch, the college occupies Swindon’s former railway village.

4.