7,00 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Armida Publications

- Sprache: Englisch

Melissa Hekkers recounts her footsteps as she joins the journey of thousands of refugees seeking safety in Europe.

Pushing the boundaries of creative non-fiction, Hekkers recreates the moments that marked her the most, whilst volunteering in refugee camps in Lesvos, Greece, and during her ongoing involvement with the refugee community in Cyprus.

Amir’s Blue Elephant is a glimpse into the sorrows of one of the biggest challenges faced by humanity today. Told through the eyes of a woman struggling to understand the realities asylum seekers are thrown into, this is the story of people fighting for the fragile right to freedom and liberty, the right to life itself.

---

“Before COVID-19, the refugee crisis was Europe’s most pressing problem since WWII. Its legacy may be longer lasting. In years to come, when children, who braved the Aegean Sea in plastic rafts, have become adults, and feel resentlfl about being rejected, they will remember the peoplr they met on Greek island beaches, vilunteers like Melissa Hekkers. And they recall that, yes, there was a welocome, there was a kindness. Amir’s Blue Elephant broght a smile to a child of the Syrian War. A smile he will hopefully remember forever. Hekkers’ memoire is a very personal contribution to the early history of the 21st century.”

Malcolm J. Brabant, PBS NewsHourspecial correspondent

“From the infamous hosting facility of Moria to the darkest parts of cities in Cyprus, “Amir’s Blue Elephant” gives an insight to the hardships faced by refugees and migrants upon reaching European shores. Melissa’s experiences with refugees over time, shared in a clear and reader-friendly style, provide an opportunity to the most fortunate to reflect on what could and should be done to alleviate the loneliness of refugees in our midst; and most importantly to enable them to call their new countries a home. An antidote to the highly politicised and dehumanising discourse in our times.”

Emilia Strovolidou, UNHCR, Cyprus

"Melissa Hekkers' impassioned account of her time working with refugees on Lesvos and in Cyprus is unflinching and refreshingly honest. She highlights the messy, heart-breaking, human stories of those she meets and refuses to settle for easy answers."

Tabitha Morgan, Writer & Broadcaster

"Amir’s Blue Elephant is about keeping an open-minded approach to the world. Melissa tells us, in a most sincere way, how she feels about the persons who migrate in order to find a better life. Most importantly, with Amir’s Blue Elephant, she reminds us not to get used to human suffering, and she never points the finger at anyone. Her writing contributes to keeping our human empathy alive. After reading her book, you naturally come to the conclusion that the only solution is to cooperate all together in order to find structural solutions to this problem which concerns us all."

Françoise Gustin, Ambassador of Belgiumto Greece

“Read AMIR in one breath: disturbing, moving, engaging, with a frontal gaze at current issues.”

Ruth Keshishian, Moufflon Bookshop

“Hekkers delivers a true tour de force--with her lyrical and evocative writing, she shines a mirror on the humanity that unites us all. ”

Mellisa Felix, Head of Casale Flaminia Writing Residencies

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 173

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Ähnliche

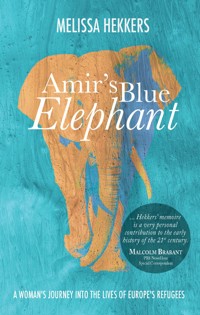

Amir's Blue Elephant

A woman's journey into the lives of Europe's refugeesby

Melissa Hekkers

Copyright Page

Copyright © 2020 by Melissa Hekkers

All rights reserved. Published by Armida Publications Ltd.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without permission of the publisher. For information regarding permission, write to

Armida Publications Ltd, P.O.Box 27717, 2432 Engomi, Nicosia, Cyprus

or email: [email protected]

Armida Publications is a member of the Independent Publishers Guild (UK),

and a member of the Independent Book Publishers Association (USA)

www.armidabooks.com | Great Literature. One Book At A Time.

Summary:

Melissa Hekkers recounts her footsteps as she joins the journey of thousands of refugees seeking safety in Europe.

Pushing the boundaries of creative non-fiction, Hekkers recreates the moments that marked her the most, whilst volunteering in refugee camps in Lesvos, Greece, and during her ongoing involvement with the refugee community in Cyprus.

Amir’s Blue Elephant is a glimpse into the sorrows of one of the biggest challenges faced by humanity today. Told through the eyes of a woman struggling to understand the realities asylum seekers are thrown into, this is the story of people fighting for the fragile right to freedom and liberty, the right to life itself.

[ 1. SOCIAL SCIENCE / Emigration & Immigration, 2. SOCIAL SCIENCE / Refugees, 3. SOCIAL SCIENCE / Volunteer Work, 4. SOCIAL SCIENCE / Human Geography, 5. SOCIAL SCIENCE / Social Classes & Economic Disparity, 6. BIOGRAPHY & AUTOBIOGRAPHY / Social Activists, 7. BIOGRAPHY & AUTOBIOGRAPHY / Women,8. BIOGRAPHY & AUTOBIOGRAPHY /Editors, Journalists, Publishers ]

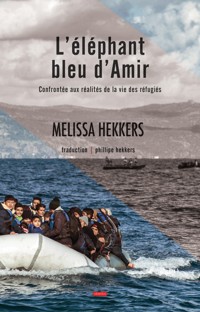

Cover

Photo by Orlova Maria on Unsplash

Photo by Keyur Nandaniya on Unsplash

Photo Credit: Antonis Farmakas

This memoir is a truthful recollection of actual events in the author’s life. Some conversations have been recreated and/or supplemented. The names and details of some individuals have been changed to respect their privacy.

1st edition: September 2020

ISBN-13 (epub): 978-9925-573-32-5

Acknowledgements

The journey that led me to write this book is very close to my heart. It's through the realms of a humanitarian crisis that I met myself. It's also where I met hundreds of people who cultivated my passion for humanity, for righteousness and for a way of life that meets eye-to-eye with my virtues and visions. It can only be symbolic to want to thank each of these people. Yet there are specific people who have contributed to making this book a reality, and this is why I want to single them out here. The Casale Flaminia Residency, Ralph Overbeck in particular and Mellisa Felix, my mentor, for your support, encouragement, trust and abundant guidance. My Publisher (Armida Books), Haris Ioannides, for embracing my work and pushing on through, my parents and family for an ever growing faith in my never ending (ad)ventures, my closest of friends -you know who you are- who insistently remind me that following your dreams is non-negotiable and my daughter, for all her brightness.

Table of Contents

Copyright Page

Acknowledgements

Dedication

Chapter 1 - Breaking Free

Chapter 2 - The Departure

Chapter 3 - Finding Lesvos

Chapter 4 - The Truth

Chapter 5 - The Storm

Chapter 6 - Selfies & Ambiguities

Chapter 7 - Parting

Chapter 8 - Alternate Dimension

Chapter 9 - Beni’s Reality

Chapter 10 - The slap

Chapter 11 - Coming Home

About the Author

Dedication

For Lara

Chapter 1 - Breaking Free

My work desk was neat and tidy. Like it was every morning. The only remains of last night’s shift was my empty coffee cup. The lingering brown coffee grounds at the bottom of the cup resembled the way I felt. Dry. Stagnant. Empty. Not much to say for myself; unless someone was willing to read my coffee cup; delve into its whispers. I guess that would be a solution to finding my way around my next steps. Let someone else envision my life for a while. Day in, day out, the gloom of the newsroom impelled me to break loose; forget about everything and seek the truth elsewhere than within the news headlines.

As a journalist, I had been preoccupied with the ever-growing refugee crisis for the past ten years, at the very least, although it somehow felt like much longer than that. By nature I felt that I had been a migrant all my life. I had migrated from my birth country with my mother at the age of eight and I had never really acquired a new home; or the feeling of belonging that I imagined was attached to it. This was one of the reasons why my career as a journalist very much revolved around migration issues. It spoke to me.

Yet at the peak of the crisis in 2015, I felt that my purpose to divulge the truth about what really lay behind the movement of peoples wasn’t being met. I was done with reporting on the number of boats that crossed the shores of Turkey and Libya into Italy and Greece. I wasn’t interested in the battles NGOs fought with local authorities on the ways the influx of people was being (mal) handled. I was weary of government spiels on the immensity of the problem. And I was silently witnessing the urgent needs of people being uprooted from the destinies they had worked on for an entire lifetime to realise. Just like thousands of us around the world, I was guilty of assessing their truth based on assumption.

“So what you working on today?” blurted Oliver, my editor-in-chief, a tall, middle-aged man who carried himself well and whose grey goatee defined his composure. Over the years, he had defiantly managed to keep me on my toes and in consequence I repeatedly second-guessed the actuality I purveyed through my words. Deep down, his judgement centred on an ambiguity I knew wasn’t justified yet his position of power allowed it. Rarely did he accept any piece of my writing without having something to add, something to nitpick.

“Is this geezer real?” he asked me, pointing at one of the stories I had written for the morning paper. He was scanning the newspaper as he paced around the office. As I watched him prance around, he stretched his arm out to switch the radio on.

“Those were his words Oliver. Word for word,” I replied as a matter of fact. My tone of voice indicated that I had no time for his whims. I had written a story about a family of stateless Syrian Kurds who were on a hunger strike outside the presidential palace, seeking Cypriot nationality and consequently freedom of movement. I despised the way he dismissed people’s opinions, their aspirations, and merely anything that wasn’t logically sound. He disregarded any piece of writing that had a human angle to it. He wanted numbers. He wanted facts. He wanted the cold reality.

“But do you believe him, is the question,” he added speaking slower than usual with the irritating smirk he so often made use of. He was an avid football fan who brought his four sons up with a vengeance. He thrived on asking rhetorical questions that shattered my approach to news writing, yet throughout the years I had always maintained that what true journalism was really about was discovering the truth and more importantly letting others tell the story, unfiltered through my own biases and understandings.

The sound of the fax machine behind us jolted me back to Oliver’s question. As if he’d never left the ’90s, he still relied on these relics. The fax machine should have been something of the distant past yet he lived by it; at times I joked that press releases printed on fax paper descended from another era. But before I managed to formulate a full sentence in response, he had already scanned the fax he had just picked up from the fax machine and threw it on my desk like a Frisbee.

“Here’s a story. Two English Typhoon jets are being deployed from the RAF’s base in Limassol to back the military action against the so-called Islamic State in Syria. Write something about that. For the website. It must be up on Reuters already.”

“Jesus,” I muttered to myself as I scanned the document. I had just booked a one-way ticket to the Greek island of Lesvos[1] to get a closer look at what the refugee crisis looked like on the ground. On the one hand, I wanted to get a concrete understanding of what Syrian people were fleeing from, what their take on the war was, what they were enduring but, more importantly perhaps, I was seeking to stand by them on their journeys. I wanted to tell them that I intrinsically understood what it meant to ‘lose’ your home, how it felt to have to deal with migration bureaucratic whims and what was implied when you found yourself in a position where your mother tongue has no power and in a place where your means are totally insufficient to build the life you hope for.

“All I need is jet planes flying along with me,” I continued to mutter to myself as I reread the facsimile.

I swirled around on my chair in an attempt to get up to go and fill my coffee cup with some substance. As I stepped forward, lifting myself off my chair, I accidently pulled the Internet connection wire out of its socket. Nothing was easy or perhaps this was the beginning of another underlying story that would define my day. I bent over and knelt down to reconnect the wire just as I heard Oliver re-enter the room.

“Need any help there love? It’s a bit early to be on all fours, no?” he sniffed.

My blood pressure hit the roof but, closing my eyes tightly shut, I forced myself to remain steady. Once I had made my way out from under my desk and perhaps plucked enough courage to speak my mind, Oliver had disappeared.

I patted the dust I had collected from under the desk from my knees, I lifted my coffee cup off the desktop and headed for the door. I knew it was going to be a long day.

[1] Lesvos (also called Lesbos or Mytilini).

Chapter 2 - The Departure

From the day I booked my ticket I had doubts about my choice. Admittedly, I was taking a break from the newsroom I so resented. In many ways I think I believed I could change the world by seeking and acknowledging its cruelty. But in truth, as a single mother, I was leaving my 8-year-old little girl behind in order to attend to other people’s needs.

Dara was young, bold and as clumsy as I was. Light in her being but hefty in her will, she never ceased to surprise me.

“Mom, you know my blue elephant? The teddy I won at that festival we went to in the mountains?” she called out from her bedroom as I meticulously packed the last bits and pieces I envisaged I may need.

I shuffled around in contemplation, holding a flash light in my right hand and a map of Lesvos I had insisted on taking with me in the other. As if a paper map would guide my way and not the calamity of Lesvos’ plight.

“Euh, I think so… You mean the one with the chequered bib? I think it’s on your bed.” Dara was forever losing things; she depended somewhat on my photographic memory to find her own belongings.

“I know it’s on my bed mom, it’s here,” she appeared in my bedroom holding the blue teddy in her hands, waving it from side-to-side, confirming that she could find things if she really put her mind to it. I was about to comment but opted to remain silent. I was leaving tomorrow after all; better not stir things.

“Take it with you,” she said, throwing it on top of my rucksack. “Give it to someone there. A refugee. I don’t need it. I have exactly the same one, the one that Zara gave to me. Remember? I love his trunk. It’s so soft,” she added taking the elephant back in her clasp and stroking it with admiration.

She stared at me as she tenderly stroked her teddy. I was dumbfounded by her boldness. She wanted to be part of the venture I was about to engage in and obviously her only way to do so was to share what she could: her teddy bear collection. Willingly she wanted to give one of her teddies away, admittedly a duplicate, yet by doing so I knew she was with me, all the way. I squeezed her so tight that evening. Without knowing it, she had propelled me into believing that I could potentially change the world, because if she, an 8-year-old, could understand my quest to help those in need, I had already won half the battle.

Our morning call wasn’t the one that I had envisioned. Both tucked in bed, under the warmth of my flowery duvet, I opened my eyes and savoured the details of my sleeping child’s face. It wasn’t until I looked at my alarm clock that I sat up in distress.

“Shit! Dara, wake up my love. We’re late. I didn’t hear the alarm. Damn it,” I added as I jumped to the floor. I slipped on the clothes I had lazily taken off and left on the floor the night before and headed for the corridor.

“I’m going to make your lunch box, but get your clothes on. Do you have PE today? I think I put a clean pair of shorts in your drawer. And don’t forget to brush your teeth!”

Dara seemed completely oblivious. Hiding under the covers, she didn’t move. I walked into the kitchen with a thousand thoughts in my mind. Almost like a checklist. Lunch box. School. Cat food. Water plants. Lock the door. Don’t forget passport. Call mom. Warm hat. Money.

“Mom! Do you know where my shoes are?” She was up and about.

“Here. Slip these on. I’m ready in five. Are you ready? I didn’t put cucumber in your sandwich; I didn’t buy anything fresh ’cause I’m leaving. But I have an apple,” I mumbled as I slipped my coat on and grabbed my car keys.

We sat silently in the traffic that led us to Dara’s school. It was sunny but the cold wind we endured to get to the car had left imprints on our bones. I alternated between sitting on my right and then left hand in an attempt to warm them up. Dara sat still by my side with her hands tucked into the sleeves of her jacket. I turned the radio on, a morning ritual I had adopted ever since I had started to work in the newsroom. It helped me formulate an idea of what I was going to deal with throughout the day. It gave me time to make myself a cup of coffee once in the office, only to be tied to my computer screen for hours on end.

“…The full horror of the human tragedy unfolding on the shores of Europe was brought home this morning…” I looked at Dara to seek for her reaction. I could tell she was aware I was looking at her, but she just looked out straight ahead with a blank look on her face.

“...Images of the lifeless body of a young boy – one of at least 12 Syrians who drowned attempting to reach the Greek island of Kos – reflect the extraordinary risks refugees are taking to reach the West… The picture, taken this morning, depicts the dark-haired toddler, wearing a bright-red T-shirt and shorts, washed up on a beach, lying face down…”[1]

I held my breath. I changed the channel. This wasn’t the time to delve into this.

“So, I’ll call you when I arrive?” I eventually managed to say as I reached for Dara’s right leg. “I’m going via Athens so I’ll arrive early evening.”

Dara just nodded. Generally, I travelled a lot. I didn’t feel absent from her life, it just bothered me that she wanted to travel with me and that I couldn’t take her along. Either she was at school, or I was travelling for work. On other occasions I just didn’t feel comfortable taking her with me. I had spent the last couple of years exploring the Middle East. I was far from being ready to introduce her to these countries for they were so alive, the cultures so vibrant, the life in these vicinities so simple yet so complicated and perhaps I wanted her to understand the complexities of the region before she set foot in them. But this time was different. I was scared. Any travel is an experience but this time around I was travelling to a humanitarian crisis. No joke.

I shook my head in discontent. My mind drifted to the meeting I had had with Nikki a couple of days back. Nikki was an experienced American relief worker who had just returned from Lesvos herself. Her words rang clearly in my mind.

“What worries me is the threat of cholera developing in one of the camps. People have been using the top of the hill to relieve themselves and now that the rainy season’s kicked in, all that waste is making its way down the hill and into the main area of the camp. If any of that waste is contaminated, you’re looking at a potential epidemic. It’s shocking.” She had spoken within the confined walls of a university classroom she had borrowed to inform anyone interested or planning on making their way to Lesvos. She was a big lady, sharp with her words, explicit in her thinking, passionate about humanity yet extremely factual.

Up until that meeting I hadn’t thought about the potential health hazard I was walking into. I was more concerned about the health condition of people on the move, their well-being.

“How can we stop this?” I had asked her as I rolled a cigarette. I often sought refuge in my cigarette smoke. In many ways, cigarettes had become my companion. Too many of the cigarettes I smoked went by unnoticed, but some of them, like this one, induced contemplation, assisted me in my processing, gave me a window of time to go within and seek.

“Look, ideally, when you get there, you buy five or six shovels and you find a group of people to dig a trench with you, along the tip of the hill and bury it all. And then you have to try and form some sort of system whereby refugees will bury their waste into the ground each time they relieve themselves. But I’ve alerted the authorities so I don’t think you should worry about that right now.”

We were now sitting opposite each other. Everyone else had gone. She was tired from her journey. I could tell she had seen things she wasn’t conveying. I sought her reassurance but she wasn’t in a position to provide that. She very much stuck with the numbers. She gave away concrete facts. Oliver came to my mind. It struck me how similar they were to each other, particularly at that moment, for I was sure Nikki had an emotional layer to her she wasn’t revealing. It was impossible to talk to either of them about what they imagined it felt like to lose your home, your family, your aspirations. Neither of them understood the perpetual void your identity slithers through as you become more and more distant from your childhood memories. I had experienced that feeling on so many occasions and I had found solace in very few people.

“Once you get there, the best thing to do is boil as many eggs as you can, as often as you can. These people are malnourished and weak. Eggs are full of protein and the beauty of them is that they have a shell around them, so you can pass them around, people can keep them for later, they’re easy to handle and they can’t be contaminated with anything. I’ve seen volunteers walk on camp giving out chocolates. Sugar’s the worse thing to give out to people in distress, particularly when they’re coming off the boats, wet, in shock.” Shaking her head from side-to-side, she hadn’t realised I had drifted away from the conversation.

“It really annoys me when I see thoughtless actions. If you don’t know, ask for Christ’s sake! So much time and energy is wasted on pointless and at times dangerous initiatives,” she paused and watched me light my cigarette as I pulled my eyes away from her. “Just give them eggs, good protein. Nourishment. It’s simple,” she concluded in a different, calmer tone.

Suddenly I snapped out of my trail of thought and realised we had reached the school gates. I bit my lip in guilt. Once again my mind had travelled to the refugee crisis, disregarding what was going on around me altogether. I should have used this time to connect with Dara. “Damn it Christine,” I judged myself.