29,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

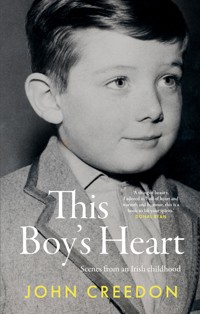

- Herausgeber: Gill Books

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

In The 1930s, Irish schoolchildren were tasked with asking their oldest relatives and neighbours about stories and superstitions from times past so that ordinary people's lives could be preserved and celebrated. What those schoolchildren wrote in their copybooks resulted in the National Folklore Archive's Schools' Collection, and this book contains a selection of its best stories. With chapters on ghost stories, agriculture, forgotten trades, schooling and pastimes, this is a people's history of Ireland. There are incredible stories of self-sufficiency from an era when everything on the table was homemade. Discover how people survived on flour, milk and potatoes, and how fabric, dye, soap and candles were made by hand. There are delightful memories of childhoods spent outdoors, gathering nuts and berries, playing Tig and fishing; while stories of folk remedies reveal how wellbeing in Ireland had long been a heady potion of miraculous medals, doctors, healers, holy wells and pilgrimages. With each chapter introduced and contextualised in John Creedon's inimitable voice, this beautiful treasury of tales is a stunning tribute to ordinary Irish people and how they lived long ago.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

We were all children once, so I dedicate this book to my eleven siblings: Norah, Carol Ann, Constance, Geraldine, Vourneen, Don, Rosaleen, Marie-Thérèse, Eugenia, Cónal and Blake.

CONTENTS

Cover

Title Page

Dedication

Introduction

1.Supernatural Beings

2.Mythical Heroes

3.Ghost Stories

4.Life on the Land

5.The Old Trades

6.The Food We Ate

7.Home Crafts

8.From Hedge Schools to National Schools

9.Games and Pastimes

10.Folk Medicine

11.Weather

12.Religion

13.Hard Times

14.Feast Days and Celebrations

Acknowledgements

Copyright

About the Author

About the Schools’ Collection

About the Illustrator

About Gill Books

INTRODUCTION

‘Thousands of old people dictated their own firsthand experiences from the 1800s and the traditions that dated back centuries further. With every story we’re introduced to a little boy or girl, with their own personality and turn of phrase. In some you can almost hear the melody of the local canúint. I trust many of these accounts will spark memories of your own childhood and the people who coloured it. I know they did for me.’

EVELATION OCCURS WHEN you least expect it.

My father and I agreed on most things: never outstay your welcome, never boo a fellow human being, and never tire of the road. From the age of fifteen, Connie Patrick Creedon had been driving Model T trucks for his father. He hauled lorry-loads of turf for CIÉ Road Freight during the Emergency and then drove Expressway buses until he retired to run the little shop that helped feed and educate his twelve children. In his old age, freed from the seven-day-a-week grind of a late-night cornershop, he picked up where he left off, packed up his little bag and hit the road.

He loved to sing in the car and most of his songs were songs of the road. Songs like ‘I’m a rambler, I’m a gambler’ or ‘The Jolly Beggar Man’, which captured many of the joys of the open road:

… of all the trades a’ goin’, sure beggin’ is the best, for when a man is tired, he can sit and take a rest.

These were songs of cowboys, hobos and drifters, all of them rollin’ along with the tumbleweed.

On a stopover during one of the road trips that lit up his final years – a journey he and I took to Mayo in July 1998 – he stayed up singing and playing the harmonica till early morning. After a few hours’ shut-eye, we were heading out of Westport just ahead of the sheriff and his posse. I asked if he had ever climbed Croagh Patrick, given that it was named Patrick after him.

‘Christ, my climbing days are well over, but c’mon so, we’ll take one quick belt out the road to make sure ’tis still there.’

Having ensured the Reek was still standing, I suggested we drive over to Murrisk to view John Behan’s National Famine Memorial, which had been unveiled by President Mary Robinson the previous year.

‘God forgive me my sins, but you’re worse than your sisters for d’oul art. Do you expect me to drag my poor oul bag of bones out of the car again?’ he groaned.

I did, and he did.

The large bronze installation depicts a coffin ship with skeletal figures. Set against the backdrop of Clew Bay and pointed westwards to America, the memorial is a dramatic reminder of the millions of people who died or were displaced during the Great Famine of 1845–49. My father was silenced by the power of the piece. With his two hands clasped behind his back, he limped slowly around the memorial, issuing the occasional tut or sigh to himself.

He hardly spoke all the way to Ballinrobe. I glanced once or twice to check if he had fallen asleep.

‘What’s going on in your head?’ I asked.

‘Yerra, those poor people in the Famine, God be good to them, they suffered something awful.’

‘I know … awful. Do you think they’d be proud or disappointed with the way Ireland is today?’

For the most part, my father never theorised much about anything. It was always a narrative, always a story to illustrate his understanding of a subject. I once asked him if he believed in angels: ‘Mother of God, I don’t know anything about that, but did I ever tell you about the time your grandfather thought he saw a ghost out towards Graigue?’ On this occasion, I pressed him for an opinion.

‘Do you think the people who suffered in the Famine would be happy or disappointed with us? You know what I mean, winning independence and the Celtic Tiger and all the rest of it?’

‘I have no idea about that, but I used to know a man who was in the Famine,’ he said, staring straight ahead.

‘In the Famine?’ I chuckled. ‘How could you possibly have known a man who was in the Famine? Sure, the Famine was 150 years ago.’

‘Well, I’m telling you now, I did know a man who was in the Famine.’

‘Go on, so – tell me.’

‘From the time I was five or six years of age, I used go out with Denis Lucey in my father’s truck to deliver meal around Bantry. Denis used call to an old man, named Sullivan I think, who grew up in Glengarriff and who lived well into his 90s. That man told us, not once, but several times, that when he was a small boy, the Famine was raging back West along. He said there was a man who would come out from Bantry Workhouse in a pony and wicker cart, known as the ‘ambulance’, to collect the dead and dying. One day, the driver stopped in Glengarriff and tied the horse outside where the hotel is now.

‘Sullivan said “I was with some other children, and we ran up to see the bodies inside the ambulance. I had a little sally rod that I pushed in through the weave of the wicker and poked a dead man in the shoulder. But the man managed to raise a hand and push the rod away. Clearly, he was still alive, but he was on his way to the workhouse nonetheless, God help us. And although I was only a small boyín at the time and didn’t know any better, it’s to my immortal shame that I did such a terrible thing.”’

Now it was my turn to be silenced.

I struggled with the maths. The Famine raged from 1845 to 1849. My father was born in 1919 and would have met Mr Sullivan in the mid-1920s. If, as old Mr Sullivan said, he was only a ‘small boyín’ during the Famine and went on to live to be over 90, then he could easily have been recalling his eyewitness account right into the 1930s, not to mind telling my father a decade earlier. So there was indeed ample time for each man’s life to have overlapped the next.

Floored by this revelation, I turned to my father and said, ‘How come you never told me this before?’

‘Because you never asked me,’ he replied, trying to pin the blame on me. In truth, he had forgotten all about it, until John Behan’s memorial sparked the memory and then, suddenly, there I was, listening to a man recall a firsthand account of the Great Famine.

Little did I know that my compadre was going to ride off into the sunset himself the following January.

The great lesson I took from that trip is … ask! That’s precisely what the Irish Folklore Commission did when they set up the Schools’ Folklore Collection in 1937. They asked. They asked schoolchildren to ask their parents and grandparents for their recollections. There was no time to lose. Here was a people whose culture and ways had been driven underground for centuries. Now there would be a drive to secure their stories in a national memory bank.

Remember, just fifteen years earlier, in June 1922, during the Irish Civil War, the Four Courts came under heavy shelling from Free State troops. The subsequent fire at the adjoining Public Records Office destroyed a wealth of information on births, deaths and burials. These priceless written records were erased forever, but now this oral history project would attempt to gather a social history from the memory of the living.

The scale and significance of the project cannot be underestimated. The Deparment of Education responded to the Irish Folklore Commission’s call with enthusiasm. With the support of the Irish National Teachers’ Organisation, they enlisted 50,000 schoolchildren in the 26 counties of the then Irish Free State. They would write over half a million pages of manuscript. Bailiúchán na Scol, or the Schools’ Collection, is the result.

Today, whether we like it or not, virtually every detail of our existence is recorded on CCTV, phones and online databases. It’s unlikely that our story will fall through the cracks ever again. But in these pages, amidst the chalk-dust classrooms and cleared-away kitchen tables of 1930s Ireland, we meet little boys and girls documenting, in their best handwriting, the ‘story of us’. Many of their elderly sources had little education and could neither read nor write themselves. But the Irish word for folklore is béaloideas, literally meaning ‘mouth education’ or ‘instruction’, and that’s exactly what happened. Thousands of old people dictated their own first-hand experiences from the 1800s and the traditions that dated back centuries further. With every story we’re introduced to a little boy or girl, with their own personality and turn of phrase. In some you can almost hear the melody of the local canúint. I trust many of these accounts will spark memories of your own childhood and the people who coloured it. I know they did for me.

I am so grateful for those long car journeys where my father told and retold his stories. I have also come to recognise the huge debt of gratitude we all owe to the thousands of Irish schoolchildren who formed the great folklore meitheal of 1937. This golden harvest is their great legacy to us.

1

SUPERNATURAL BEINGS

‘The threshold between this life and whatever lies beyond has occupied the human mind since Adam and Eve were babies. Like most cultures, when we don’t know, we’re forced to invent. The Celtic mind was particularly fertile.’

NEVER HAD A first-hand encounter with the banshee myself. However, on the night my grand-uncle Jeremiah was waked in Inchigeelagh, all the dogs in the village spent the night howling and wailing. They began their ológoning shortly after my father and I arrived from Cork. By the time the priest arrived, the blood-curdling keening had grown to the volume and pitch of an air-raid siren. There might have been a rational explanation. Perhaps it was ignited by the murmur of so many people gathering in the dimly lit village at an hour when Inchigeelagh and its dogs would normally be settled for the night. I remember the old men making sense of it all:

‘I s’pose they’re lonely after him. God knows, poor ol’ Jeremiah had a great ol’ grá for the dogs.’

‘Erra, he had … and they were fond of him.’

A dog is a great thing. Apart from their acute sense of hearing – the first line of household defence – their powers of perception seem to reach into that liminal space between this world and the next: a facility denied to all but the most intuitive of humans. When a snoozing dog suddenly cocks its head and points its ears, you can be sure that those little antennae have picked up something you have missed. An elderly widow, Nan Casey, and her sweetheart of a collie lived up the hill from us in Cork. If the collie ever growled at a caller to the door, Nan always closed it.

The threshold between this life and whatever lies beyond has occupied the human mind since Adam and Eve were babies. Like most cultures, when we don’t know, we’re forced to invent. The Celtic mind was particularly fertile. Even J.R.R. Tolkien, creator of The Lord of the Rings and The Hobbit, bemoaned the lack of an English mythology to match what he encountered on his trips to the West of Ireland.

The banshee was one of the busiest and most feared of Irish supernatural beings, for she was the mystical harbinger of an imminent death. ‘Banshee’ is a compound of the Irish words bean (woman) and sí (fairy). She was described by those who claimed to have seen her as a witch-like woman of not more than a metre in height who wore a cloak. She would swoop over a household, issuing a spine-chilling wail to herald the imminent death of some poor misfortunate within.

Another female supernatural being who also features prominently in our folklore is the mermaid. Unsurprising, I suppose, given that we are an island nation and share in a global tradition of tall tales from the sea. Remember, the Vikings settled here, and their sagas would also have been shared with the seanchaí around the open fire. Irish fishermen travelled deep into the Atlantic Ocean to the rich fish stocks off the coast of Newfoundland, curiously referred to as Talamh an Éisc, meaning ‘Land of the Fish’. Even without the benefit of a degree in marine science, fishermen could still clearly observe that whales, dolphins and mermaids occupy that middle ground between fish and us. After all, they are mammals, and the females give birth and suckle their young. The water-horse also occupies this space between the water and the land and that liminal space that connects our world with another (as Gaeilge idir-eatharthú, meaning ‘betwixt and between’). It is here that the imagination is free to roam.

The protective power of iron against evil forces is a recurring theme in these stories. The iron tongs were used to ward off the banshee, and in water-horse tales, horseshoes are considered an amulet against evil powers. I have one knocking around my garden for years. I have never actually found a place to hang it, yet despite numerous clear-outs, it has never gone into a skip.

The Irish word for ‘hare’ is giorria from gearr-fhia (literally, ‘short deer’). It’s a beautiful description of the animal, and I’m delighted to include here a fine example from the ‘witch-hare’ genre, in which an old lady shapeshifts into a hare and back again. I’ve even heard it said that you should never eat a hare in case it’s your grandmother! In this tale, there’s a dramatic ‘chase scene’, with a nod to Christianity overcoming the old magic and a reminder of the cruel ‘othering’ of people who are different from the norm.

While researching a television programme about the Hag of Beara, I was reminded of how elderly single women have often been dismissed as crones, witches and hags – and the fear of strange women exhibited in these otherworldly tales is plain to see. This is not exclusive to the Ireland of the past, as the term ‘crazy cat-lady’ is now liberally applied to older women displaying any signs of eccentricity. Military propaganda dehumanises the enemy by name-calling, referring to them as ‘Krauts’, ‘Yanks’, ‘Commies’ and so on. In Christian culture, the snake and cloven-hooved goat have been ascribed devilish characteristics. Is this the same motivation that drives our need to demonise the object of our pursuit, such as the hare?

But there is one figure that seemingly always evades capture. In the court of Irish mythology, the leprechaun is the jester and the rogue. I love leprechauns. Always have, always will, world without end, amen. The very first verse I ever learned by heart was William Allingham’s ‘Fairies’, which created the image of a leprechaun in my young mind. It was taught to me by my mother during a few rare days that I was off school with chickenpox, when we had each other’s undivided attention.

Up the airy mountain,

Down the rushy glen,

We daren’t go a-hunting

For fear of little men;

Wee folk, good folk,

Trooping all together;

Green jacket, red cap,

And white owl’s feather!

I wanted a leprechaun and, encouraged by my dad, I rummaged in every ditch and sceach, like a Jack Russell after a rabbit. There’s a spot on the old road from Cork to Killarney, at a bridge just west of Ballyvourney, where on the day I sat the entrance exam for secondary school, my father showed me where he had once sighted a leprechaun. It was the only time he had ever caught a glimpse of the little manín. But where there’s a sighting, there’s hope. To this day, if I spy a rainbow when driving along the motorway, I’m impulsively drawn to investigate … or at least pull in at the next filling station forecourt to buy a lottery ticket.

Reported sightings of leprechauns are so rare these days, I fear they may be near extinction. We all have a duty to maintain the wild places in the Irish countryside and maintain a landscape where the wee folk can get on with their own mischief. Otherwise, it may fall to future generations to try to reintroduce leprechauns to the wild.

She raised the death cry

SCHOOL:Ballynarry, Co. Cavan

TEACHER:E. Mac Gabhann

COLLECTOR:Hugh Sheridan

Some years ago there dwelt in one of the midland counties of Ireland a rich farmer, who was never married, and his only domestics were a boy and an old housekeeper named Moya. This farmer was well educated and was constantly jeering old Moya, who was extremely superstitious and pretended to know much about witchcraft and fairy world.

One November morning this farmer arose before daylight and was surprised, on entering the kitchen, to find old Moya sitting over the fire and smoking her pipe in a very serious mood. The farmer asked in wonder why was she up so early and the old woman said, ‘I am heart-scalded to have it to say, but there is something bad coming over us, for the banshee was about the house all night and she has almost frightened my life out with her bawling.’ This farmer was always aware of the banshee having haunted his family, but as it was some years since she had last visited the house, he was not prepared for old Moya’s announcement. He asked old Moya about the banshee’s appearance and when he heard all, he ordered her to prepare his breakfast, for he said he had to go to Maryborough that day and he wanted to be home before night.

The old lady advised him not to go that day and she said, ‘I would give my oath that something unlucky will happen to you.’ But the man was not one to take advice; after taking his breakfast he arose to depart. It was very cold and, the man having finished his business, he went to a public house to get some drink, and to feed his horse. There he met an old friend and glass, and they did not find time pass.

When old Moya found the horse at the stable door without his rider and the saddle covered with blood, she raised the death cry and a party of horsemen set out to seek him, and at the fatal spot he was found stretched on his back and his head almost in pieces with shots. On examining him it was found that his money was gone and a gold watch taken from his pocket.

‘Give me back my comb’

SCHOOL:The Rower, Co. Kilkenny

TEACHER:Labhaoise Nic Liam

INFORMANT:Mrs. Brennan, around 50 years old

About one hundred years ago, there lived in a house not far from the church of the Rower a farmer and his wife who were famous for giving charity and lodging to the travelling poor. They kept a servant girl who was a bit gay and reckless. She was in the habit of going out at night to take a ramble. One night when returning, she took a short-cut in through the orchard. The path led in by the gable end of the house. In the end there were two windows, one a couple of feet from the ground and one at the top of the house.

When the girl was passing by the window she saw a woman dressed all in white sitting on the window sill combing her hair. The girl, thinking it was her mistress who was trying to frighten her, snatched the comb and ran in. She had scarcely reached the door when she heard three weird unearthly cries. The girl fainted and the people of the house didn’t know what to do. The woman in white continued to cry out, ‘Give me back my comb, give me back my comb.’

Next night there came a poor travelling man looking for lodging. The mistress made him welcome, and gave him his supper, and put him to rest on the settle. After a while he noticed that the girl who used to be so gay seemed very dull. He asked the cause, and was told of her adventure of the night before. He told her she was very foolish, and never to meddle with anything that did not meddle with her, that woman was the banshee, and that she was sure to come again to look for her comb. Shortly after they heard the cries again, ‘Give me back my comb.’

The travelling man told the girl to redden the tongs in the fire and catch the comb with it and put it out through the end window. She did so, and it was well for her that she didn’t put out her hand with it because the banshee was so mad she bent the tongs with the grab she made at it.

The caoining

SCHOOL:Drumlusty, Co. Monaghan

TEACHER:Seán Ó Maoláin

INFORMANT:Edward Jones, age 60, Rahans, Co. Monaghan

‘The Banshee’ is supposed to cry for certain people. Therefore when some families hear the Banshee crying, they know that someone is dying belonging to them.

About a half mile from Drumlusty N.S. in the direction of Inniskeen, there are ruins of a dwelling house. A man named Walshe and his family lived there the time of the ’98 Rebellion. His wife died following the ‘CAOINING’ of the Banshee, and soon afterwards two of his children became ill and died, each death being preceded by the ‘caoineadh’ of the banshee. Soon afterwards another of his children became ill; late at night the door of the house was opened, and a brown hooded figure glided in and commenced caoining over the sick child. The man, becoming exasperated, seized the tongs and threw them at the ‘Banshee’. It disappeared at once, the child got well, and despite deaths in the family afterwards, the ‘Banshee’ was never heard ‘caoining’ them afterwards.

CAOINING, caoineadh: keening, crying.

A most unearthly cry

SCHOOL:Corracloona, Co. Leitrim

TEACHER:Pádraig Ó Caomháin

INFORMANT:Mrs. B. McMorrow

The old people around this district firmly believed in the banshee. I often heard my mother say that there were certain families that were always ‘cried’. These families were the McGowans, the Gallaghers, the Keanys, the Meehans and the O’Briens. I heard my father say that he and an uncle of his heard the banshee crying one night just before an old Keany woman died. A McGowan man lived beside us. He had a sister married down near Derrygonnelly, Co. Femanagh. Before this sister died the story goes that they heard the banshee. I also heard other people saying that they heard the banshee and it always foretold the death of some person.

I had a strange personal experience in this connection. On the night of the 14th of March 1919 (the time of the big flu epidemic) my sister and I went out at 10 o’clock to get some turf to ‘rake the fire’. Suddenly we heard a most unearthly cry. It started about a mile away from us and ran along the ground for about half a mile. Then it began to ascend and went up, up, up, getting fainter as it went, until it died away in the sky. We never heard anything so weird and concluded that it must be the banshee. We went home and told our people that we heard a banshee. They laughed at us. It happened that our next door neighbour, Mrs. D–, whose maiden name was Gallagher, took the flu that night and was dead that day week.

The white hare

SCHOOL:Clifden, Co. Galway

TEACHER:An Br. Angelo Mac Shámhais

COLLECTOR:Connie McGrath, Clifden

INFORMANT:Mrs. J. Lysaght, Clifden

Long ago there was a student from Ballynahinch in France studying for the priesthood, and a year before his ordination he was home at his native place. He was always a keen sportsman and his people were ever proud to have a fine hound.

About this time there was a lot of talk about a white hare that was often seen on the slopes of the Twelve Pins in the direction of Maam Valley. It was said that this hare used to suck the cows and many times the cows belonging to the poor people of the district would come home in the evening and would have not a drop of milk. Some women also complained that the milk would produce no butter and they said that the white hare was surely a witch. The student heard all this talk and he said that he would chase the white hare. Some old people in the place said that it was often chased but got safely away from all hounds, and said that there was no hound to kill that hare except an all-black hound. The student enquired around the neighbourhood and at last discovered an all-black hound near Oughterard.

It was a fine May morning when this lively young man set out with his all-black hound to chase and kill the white hare on the hillside near Ballynahinch. After a short time up gets the hare in a RUSHY CURRAGH, and headed for a valley in the mountains.

The chase was very thrilling but the student had a very good view and had high hopes that the black hound would succeed. Among the rocks and round the lakes the hare kept her distance, and for over an hour it seemed as though the hound would be baffled, but still the hare was not able to get out into the open mountains. The student saw that the hare was ever trying to escape in one direction, and he kept on that side.

At long last the hare headed for a small stream that tumbled down the rugged slopes, and the hound, still in good running form, came in close pursuit. The student saw a little hut or cabin in the distance and in a few moments the hound, hare and huntsman were just beside the hut. After a few clever turns the hound was within biting distance of the hare, and just as the hound was springing to bite, the hare made one jump in a little opening that acted as a window.

The student rushed to the door, which was small, and stuffed with heather tied in a bundle, and to his great surprise saw an old woman sitting at a spinning wheel and working away as if nothing had happened. He questioned her sternly as to whether she saw a hare coming in and she denied that that was so. He looked around the cabin, which was made of bog sods, and could see no place where the hare could hide. At last, a little vexed, he walked over to the woman and pulled her off the stool, thinking that she might have the hare hidden beside her. To his great amazement he saw a pool of blood on the floor and at once it struck him that the woman was bleeding; she seemed to be out of breath.

After a few threats she admitted that she was bleeding and that she had been bitten by the hound and that she was the white hare that used to suck the cows. She promised to give up her evil ways and she did.

This woman was well known before this event. She lived alone in the hut and was never suspected of doing anything wrong.

RUSHY CURRAGH: a fen covered in rushes.

An caipín bréaghach

SCHOOL:Dromclough, Kilcarra Beg, Co. Kerry

COLLECTOR:Bridie Flaherty

INFORMANT:Mrs. Ellen Foley, 74, Mountcoal, Co. Kerry

A fisherman went down to the seashore one morning to see if any seaweed was in after the night’s tide, and saw a beautiful young girl sitting on a rock combing her hair. He said to himself, ‘This must be the mermaid I hear all the people talking about.’

She did not see him at all as her back was turned to him. He stooped and took off his shoes, and tip-toed out to the rock. He heard it always said that if you could steal her cap she would follow you. He saw the cap on the rock beside her, and he took it, and went off with it, and she followed him on. He ran for home, and she ran after him roaring for her ‘CAIPÍN BRÉAGHACH’.

He took the house of her, and there was a loft where a CLEEVE of turf could be put up. He threw the cap up there. She went into the house and asked for the cap that she could not go back to her home in the sea without it. ‘No,’ said he, ‘I want a housekeeper, and I’ll keep you now as I got you; I have no one in the house with me.’

So she sat down; he began to cook his dinner, and she got up and helped him. All the neighbours gathered in to see the mermaid. She was there for a week, and he sent for the priest and they got married. She forgot all about the sea until one day in due time a baby boy was born to them, and after five or six years they had four children.

In them old times everyone’s home was filled with canvas sheets made from flax. In that time they never washed them during the three months of winter. According as they would get soiled they would pack them up in the loft until the Spring. Then they would be washed and put out to bleach.

When the Spring came he said to the mermaid he would take a few bags of corn to the market to sell it. He went off, and she said to herself it was time to wash the sheets. She was never known to laugh during the while she was there. She put down the water and threw down the sheets. When she had last of the sheets thrown down, she found her little cap.

She made three hearty laughs that rang in the air. She then turned and kissed the little children, and put on her cap, and made for the Cashen where she saw a few fishing boats. The men tried to catch her, for they knew what had happened. She was too clever for them and made a terrible jump into the sea, and was never heard of or seen since.

When the man came home he asked where she was, and they said they did not know. The eldest boy told what happened. He saw all the clothes, and he thought of the ‘caipín bréaghach’. He searched for it, but it was gone. Day after day he went to the rock, but she did not appear anymore.

CAIPÍN BRÉAGHACH: this could mean ‘false cap’ or ‘deceiving cap’.

CLEEVE: a wicker basket.

The magic mantle

SCHOOL:Enniscrone, Co. Sligo

TEACHER:Bean de Búrca

COLLECTOR:Emily O’Connor

INFORMANT:Nora Whyte

Many stories are told about mermaids in this district. They are like human beings, except that from their waist down is similar to a fish. Mermaids have beautiful hair. Their hobby is combing their hair.

The only family that were connected with mermaids in this district were the O’Dowds, who lived in the old castle in the Castle Field. One day Chieftain O’Dowd was shooting in Scurmore Wood. He saw a mermaid sitting on a rock combing her hair. He brought her home and married her. They had seven children, and after some time the mermaid became lonely for her sea friends. Knowing this, Chieftain O’Dowd hid her mantle, but his youngest daughter saw him hiding it; the child told her mother. The mermaid was delighted; now that she had the magic mantle, she could go back to the sea; without the mantle, she would have to stay ashore. That night, taking her seven children with her, the mermaid stole from the castle. She brought them to a field near Scurmore; there she changed six of them into rocks, and took the youngest child, who told her where the mantle was hidden, with her into the sea. And the mermaid nor the child were never seen or heard of again. But the six rocks are still to be seen in the summer where the waves of the bar lap and wash over them at times. It is said that these rocks bleed every six years. If you touch each rock, you will dream of fairies that night.

The lake of the knife

SCHOOL:Carrowbeg, Co. Donegal

TEACHER:Rachel Nic an Ridire

COLLECTOR:Robert Mc Eldowney, Ballymagaraghy, Co. Donegal

INFORMANT:Pat Mc Colgan, age 87, Ballymagaraghy, Co. Donegal

In ancient times, so the people relate, there lived in Lough Skean a beautiful mermaid. Every morning, at sunrise, she used to rise from the lake and sit on a rock about three hundred yards from the shore and sing a weird ‘caoineadh’ which could be heard for miles around.

The man from whom I heard this told me that his grandfather, who had seen the mermaid, described her as the most beautiful creature ever a human being laid eyes on. Her fair golden hair fell in ripples down below her waist, while her skin was as white as snow, and her features as clearly cut as those of a marble statue. Her body from the waist downwards was covered with large greenish scales, and very much resembled that of a fish.

It is related in the district that a youth named Sean O’Connor fell in love with her but the mermaid, hearing this, knew she could never live on dry land. One morning Sean went as usual to the lake, expecting to see his love emerge and sit on the rock. For hours he waited but poor Sean, having given up hope of ever seeing her again, drew up a large knife and plunged it through his heart.

Ever since the lake has been called Lough Skian or the lake of the knife. The mermaid was often seen sitting on the rock after that but on still nights her weird caoining can be heard for miles around. It is said that she is mourning Sean O’Connor, the boy who gave up his young life for the love of her.

A beautiful mermaid

SCHOOL:Lissadill, Co. Sligo

TEACHER:Gleadra Ní Fhiachraigh, A.E. Ní Chraoibhín

A man was fishing off the coast of Raughley, about four miles from Lissadell. He saw what he thought was a fine fish and struck it with a harpoon. He did not succeed in catching it and both fish and harpoon were lost to him.

Some weeks later he was working in a field close to the shore when a very finely dressed gentleman rode on a beautiful horse to him. He talked to the man and asked him to go with him. The fisherman at first declined but was so pressed by the gentleman to go with him that he said he would if the gentleman would leave him back again. After a moment’s thought the gentleman promised to do so.

They both rode off on the horse. The horse went down to the shore and plunged into the sea and swam some yards and then descended into a cave. There on a rocky bed was lying a beautiful mermaid with the harpoon in her side. Her husband (the rider) asked the fisherman to pull out the harpoon and explained that it was necessary to bring the man who stuck the harpoon into the mermaid to remove it again; otherwise the mermaid would die.

The fisherman removed the harpoon and was then brought back to the field again. The rider explained that only for he had given a promise to bring him back again he could not have allowed him return to earth.

She can talk, sing and cry

SCHOOL:Carrowbeg, Co. Donegal

TEACHER:Rachel Nic an Ridire

COLLECTOR:Robert Mc Eldowney, Ballymagaraghy, Co. Donegal

INFORMANT:Pat Mc Colgan, age 87, Ballymagaraghy, Co. Donegal

There were supposed to be mermaids in the district long ago. There was once a man in Buttach who got married to one of them and one day when he hid her tail in the barn, he went to the town, but while one of the children was playing, he found it and brought it to her, and she put it on at once and off she went to the sea again. The children used to go down to the beach every morning to get their hair combed with her own comb and their faces washed in the salt water and it was always their own mother came up to the surface to do it for them. They were often heard crying when leaving her.

Half of the mermaid is a woman and the other a fish. She has lovely, curly, golden or yellow hair. She can talk, sing and cry. When fishermen hear her cry, they do not like to go to sea as it is supposed to be a sign of a storm. This one that I mentioned in the story is the only one I ever heard tell of coming ashore. When she is seen she is usually sitting on a rock singing or combing her beautiful hair. She uses no mirror as she can see herself in the water. There were some local families connected with mermaids in the past. When there was going to be a death in the family the mermaid came and cried outside the house. Fairies do the same thing in certain families but when they cry, they are known as the ‘banshee’.

The water-horse

SCHOOL:Annagh More, Co. Mayo

TEACHER:Mártain Ó Braonáin (also the collector)

One time a man went down to the sea and he got a water-horse and brought him home to do his work. When he had the horse a while he got a set of shoes on him. The man kept the water-horse until he had all his work done. Then he sent his son down to the sea with the horse, but the horse could not go out into the water on account of the shoes being made out of iron and the iron is blessed. The boy brought the horse to his father again and he took the shoes off him and put the boy riding on him again and they went off to the sea. When the boy was near the sea he tried to halt the horse but he could not. The horse started to gallop and he ran out in the sea with the boy on his back. When he got under the water he ate the boy and there was no more about him.

Our hero the leprechaun

SCHOOL:Parteen, Co. Clare

TEACHER:Ciarán Ó Ceallaigh

Leprechauns are small little men living in a moat or commonly called a fort and they wear a tiny cap on top of their heads, a tiny coat of green and a pair of buckled shoes. Some people say that they have a crock of gold stored away in inland places.

The oldest fairy is always the cobbler and he mends the other fairies’ shoes. He always sits under an oak tree at this work during the hot weather and he is always found here either in early morning or else in late evening. If you wish to find a leprechaun you must go very, very easy by the ditches and listen very attentively till you hear the ticks of his little hammer, and if you are in luck to find him you must be very careful to keep your eyes on him, because if you look away behind you he will disappear.

A young man was once lucky enough to catch one coming from behind; he stole on tip-toe and grabbed him by the jacket and lifted him off the ground and demanded his purse of gold.

‘She has it,’ says the imp.

‘Who?’ says the young man.

‘That lady behind you,’ says the imp.

With that the young man let go his hold and turned round quickly to catch the young lady, as he thought, but she was nowhere to be seen, and turning again, our hero the leprechaun was a hundred yards away bursting his sides laughing at the fool.

A fairy cobbler

SCHOOL:Curraghcloney, Co. Tipperary

TEACHER:Máire, Bean Uí Fhloinn

INFORMANT:Mrs. James Dalton, 42, Boolahalla, Co. Tipperary

There was once a man named Jack Reilly who set out one moonlight night to set snares for rabbits. He came home when he had them set and at about 11 o’clock he went out to see if there was anything in the snares. In one of the snares there was a hare and on the fence near the snare stood a fairy cobbler. The man was thinking if he could catch the leprechaun and get the gold from him it would be better for him than all the rabbits in the world. He made a run at the little man but he was too quick for him and ran down the hill. The man threw the dead hare after him, hoping to knock him, but when the hare struck the fairy it became alive, and up on his back jumped the fairy and left the man staring open-mouthed after him up the hillside.

A pot of withered leaves

SCHOOL:Abbeytown Convent N.S., Boyle, Co. Roscommon

TEACHER:Sr. M. Columbanus

COLLECTOR:Marjorie Carney, Easter-Snow, Co. Roscommon

INFORMANT:Mr. Martin Gaffney, Ballyfarnon, Co. Roscommon

In ancient times, the people of our district used to tell quite a number of old tales connected with the fairy folk, especially leipreachauns, but most of the old inhabitants of the district have died long since, bringing most of those old stories to the grave with them. Some of those old stories are still told by the old inhabitants, but there is one in particular told about the fairy cobbler of Lough End.

Once upon a time there lived on the shores of Lough End, which is situated about two miles east of Ballyfarnon, a poor widow and her son, Padraig Mulvany. Padraig was a very lazy fellow, and every time he got a chance he used to steal away to the fairy LIOS behind the house, and dream the day away, hoping against hope that a leipreachaun or fairy might appear and give him a pot of gold.

One day, he was sitting in the usual spot at the top of the lios when a fairy leipreachaun appeared. As quick as lightning Padraig seized him by the scruff of the neck and demanded a pot of gold. The leipreachaun, remaining quite cool, told Padraig to follow him to a hollow tree, in which the gold was hidden. Padraig seized the pot of gold quickly, but the leipreachaun, taking out his gold snuff-box, asked Padraig to take a pinch.

Padraig stretched out his hand, but the leipreachaun threw the box of snuff into his face. When he had stopped sneezing poor Padraig looked round for his pot of gold, but all he could see was a pot of withered leaves.

LIOS: an enclosure or ringfort

A small, funny-looking little man

SCHOOL:Banagher, Co. Offaly

TEACHER:Séamus Ó Maoilchéire

INFORMANT:Tom Rogers, 78, labourer, Banagher, Offaly

The leipreachaun is a small, funny-looking little man. He is a fairy cobbler and he repairs shoes for the fairies. Every night he sits on a fairy mushroom with his last and his other implements in front of him on another mushroom and, with his hammer in his hand, he mends the shoes. He has ears like an ass and a long crooked nose, but he is supposed to have a box of gold.

There is a man living in Banagher by the name of Mr. Tom Rogers who caught a leipreachaun. One moonlight night he was coming home from a gamble. It was after midnight so he took a short-cut that led by the side of an old RATH OR LIS.

He was just going past it when he heard a tapping. Crawling to the edge of the lis, he saw a leipreachaun mending shoes in the centre of it. Tom stole up behind him and caught hold of him.

‘What do you want of me?’ said the leipreachaun.

‘Where have you the gold?’ said Tom, and he making sure to keep his eye on him, for it is said that if you look away at all he will vanish.

‘Look at the big dog behind you,’ said the fairy.

‘You can’t trick me, me boyo,’ said Tom, and he caught the poor fairy by the throat. ‘Tell me where is the gold or I will choke you.’

‘It’s down under my feet,’ said the leipreachaun.

Tom looked down and when he looked up again the leipreachaun had vanished. ‘I know where the gold is, anyway,’ said Tom, and he marked the spot with a thistle and went home.

The next morning he went to the fort again with the spade. The night before there was only one thistle in the lis; now the whole place was covered with them. Tom had to go home again because he didn’t know which thistle marked the spot.

There was a poor farmer and his wife who also caught a leipreachaun. They locked him up in a chest. One night they were sitting by the fire when the leipreachaun said, ‘It’s a fine night for sowing beans.’

‘Begorra,’ said the farmer, ‘there is something in that,’ and he went out and sowed the beans. He then let the leipreachaun go.

At this time Saint Patrick was travelling around Ireland. He came to the place where the farmer lived and asked for a drink. ‘That is a fine crop of beans you have,’ said the saint. ‘Would you sell it?’

‘It’s only stalks, sir,’ said the farmer. He did not know the saint.

Saint Patrick bought the stalks, which were wattles of gold. He gave the farmer hundreds of pounds for them. It is said that it was with this gold he built all his churches and schools.

RATH OR LIS: both words refer to an enclosure or ringfort.

The stocking of gold

SCHOOL:Bekan, Co. Mayo

TEACHER:P.S. Mac Donnchadha

COLLECTOR:Patrick Kelly, Lissaniskea, Co. Mayo

The leipreachaun is a small man supposed to be living in the old forts and in the woods. He dresses in a little green jacket, red cap and tiny little shoes. The chief trade he has is shoemaking for the fairies.

There is a story told about an old man named Tom Tighe who lived near a big fort in Lissaniskea. This man used to be out very late at night. As he was a poor man, he had not much money to buy food with, so he used to set traps for rabbits and birds.

One night, as he was coming home, what should he see but a leipreachaun caught in one of his traps. As soon as the leipreachaun saw the man coming he tried his best to get free, but he knew he was caught. The man took hold of him and told him to give up his gold. The leipreachaun said he had none and begged of the man to let him free. After a while the man saw the stocking of gold stuck into a little shoe. He took it out and put it into his pocket, saying to the leipreachaun, ‘If you had not told me a lie I would only keep half of the gold, but now I have it all and I’ll keep it.’

The man hurried home then, proud of his good fortune. He said he would not have to go bird-catching anymore. Then he let go the birds that were caught, for he had made up his mind that at sunrise he would go to town and buy some good food. When he arrived home he went to bed and brought the gold with him for fear it would be stolen.

The cock was crowing when he got up and he began to open the stocking. There was a very hard knot on the end of it and, try as he would, he could not open the stocking. He tried to make a hole in the stocking with his knife but he broke the blade. He sat down to think, and after a while he came to the conclusion that it was best to return the gold to the leipreachaun and catch a rabbit for breakfast.

He found the leipreachaun in the place where he had caught him the night before, cold and nearly starved with hunger. The man gave the money back to him and let him go. After thanking him, the leipreachaun asked the man what gift would he like to have. ‘I would like to be a good player on all musical instruments,’ he replied.

‘Very well,’ said the leipreachaun. ‘Your wish will be granted and you will also be able to put the bagpipes playing by itself.’ The leipreachaun disappeared then and a rabbit was caught in the trap when he looked at it.

When the man had eaten a good breakfast, he got his old bagpipes and the minute he touched them they began to play reels, jigs and hornpipes. There was a fair in town on this day and he went there with the pipes and soon a crowd of people were gathered around him listening to the wonderful bagpipes.