Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Gill Books

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

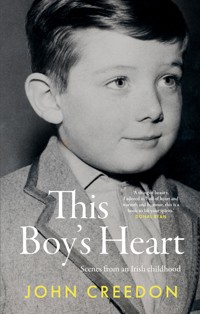

John Creedon's scenes from an Irish childhood paint a colourful and sometimes hilarious picture of a changing Ireland and the growing pains of boyhood. Set in a city-centre household bustling with humanity, the cast includes a dozen children and another dozen adults, including aunts, an American writer, an African doctor, and a Scottish bookie. The streets outside overflow with brewery horses, beat clubs, dance halls, nuns, priests, a Turkish delight shop and a pub where a child could sit up on a high stool and smoke his cigarette in peace. Creedon spent the sixties striding the streets of inner-city Cork, with summers 'farmed out' to friends and family in the countryside. His stories are set in wildly contrasting worlds, from urban exotica to spacious meadows, from tales of the open road to his classroom of over fifty boys. These are stories of friendship, fun, family and folklore. The result is a heart-warming and revealing journey into an Irish boyhood.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 337

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Author’s Note

These scenes are drawn from one decade of my life – 1960 to 1970 – and are set between the intense exotica of city-centre streets and the open meadows of the Irish countryside.

Most of us, I expect, will have experienced or witnessed injustice and cruelty during childhood. I know I have. However, I was spared the deep trauma visited upon so many children around the world. For the most part, my formative years were carefree. I grew up amongst a loving family in a country I dearly love. So it is with deep humility and gratitude that I offer this personal memoir.

I’m mindful that childhood is a shared experience and my beloved siblings, cousins and childhood friends will all have their own stories to tell. Many of them already have. So, in the spirit of an tAthair Peadar Ó Laoghaire, who wrote Mo Scéal Féin, this is my own story. I share it with deep affection and recollection.

Some names and locations have been changed.

Childhood is a fragile thing, and this book is dedicated to my grandchildren: Bonnie, Brodie, Chloe, Cody, Ella, Fiadh, Lucie, Mollie and Rosie.

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Author’s Note

Introduction

Where the Sacred Heart Is

A Rogue Is Born

Gentle as the Fawn

Sex on the Wall

Blessed Martin

Family Pass

Rite of Passage

A Neighbour’s Child

The Sound of One Hand Slapping

Putting the Fist into Pacifist

Ballybunion

Away with the Manger

Farmed Out

Tom the Traveller

Mrs Manley

Saints, Sinners and Santy

Aunty Theresa

Eurovision

One to Stop

The Orange Curtain

My Vocation

The Formica Bar

The Donkey Derby

Riding off into the Sunset

Postscript

Glossary of Terms

Acknowledgements

Copyright

About the Author

About Gill Books

Praise for the Book

Map

Introduction

With deep affection and recollection

I often think of the Shandon bells,

Whose sound so wild would, in days of childhood,

Fling round my cradle their magic spells.

On this I ponder, where’er I wander,

And thus grow fonder, sweet Cork, of thee,

With thy bells of Shandon,

That sound so grand on

The pleasant waters of the river Lee.

– Excerpt from ‘The Bells Of Shandon’, Francis Sylvester Mahony (‘Father Prout’), 1804–1866

I am in my sixty-fifth year and in the garden with my hero, Laoch, the warrior robin. I’ve been passing him sweet treats, mouth to beak, to the amusement of my grandchildren. In he comes again like a hummingbird, reverse flapping as he lowers the landing gear. We’re both in slow motion as he hovers. Two scaly claws extend, tiny drumsticks flex and retract like shock absorbers. Then, in one neat precision snatch, a dainty beak accepts the gift between my lips and, using my chin as a launch pad, he pushes off and away.

The show is over now and the children have galloped off, back indoors. Further along the northern slopes of the city, someone is playing ‘The Banks of My Own Lovely Lee’ on the ancient bells of Shandon steeple. The soft tolling of the bells summons up that minor-key melancholia of childhood memory.

A layer of ennui softly lands on the already textured soundtrack of the city below me: birdsong, children in a playground, a faint and distant ice-cream van, and an ambulance away out on the Southside.

Apart from the 13 years I spent in Dublin, I have lived my life under Shandon’s bells. When I was a small child, my bedroom window was within both earshot and eyeshot of the steeple, and on waking from a bad dream or feeling anxious about unfinished homework, Shandon’s quarter-hour bell would comfort me. With Seán Bunny, my bedtime huggy-pal, tucked under my arm, I’d lie there listening. Eventually, my attention would settle on the out-of-tune, slow notes as they reverberated and faded, drawing me with them through the sleep portal.

Although we attended the nearby Roman Catholic church, St Mary’s on Pope’s Quay, we had huge affection for Shandon. Its giant pepper-cannister tower sports the Cork colours. Two sides are faced in old red sandstone and the other two in white limestone, all topped by a huge golden weather vane in the shape of a salmon, known locally as ‘De Goldie Fish’. Each of the tower’s four giant clocks display a different time, which earned it the nickname ‘The Four-faced Liar’. But, as a neighbour of ours once observed, ‘Sure, if they all told the right time, we’d only need the one clock.’

The beautiful sadness of Abel Rudhall’s bells first rang out from St Anne’s, Shandon, to announce the marriage of Catherine Dornan to Henry Harding on the morning of 7 December 1752. Millions of Corkonians have since come and gone, but Shandon still holds the high ground and continues to serve those of the Anglican tradition.

While the repetition of the Rosary was my Catholic mantra, the Protestants provided my meditation bell.

Even now, in the garden, those chimes lull me into reflection. When asked for our earliest childhood memories, most of us, I expect, have vague, grainy home-movie images in our heads. Science would say that many of us can recall events from as early as two and a half years of age. But how do we know that a memory is a genuine eyewitness account of an event? Perhaps we are actually recalling a well-polished story, memorised from the telling and retelling of others? Family folklore is prone to exaggeration and colouring. I can visualise events that occurred before I was even born, but I’m searching now for fragments of real memoir.

For instance, there’s a photograph of my brother Don’s Confirmation and I’m not in it. I vaguely remember that I was sulking and refused to be in the photograph. I recall the gravel beneath me as I waddled away from the group.

There’s also a short, blurry memory of being in the yard of the Munster Hotel across the road from our house, where my friend Jimmy Corbridge lived before his family moved to Wales. His dad was a Welshman and chief engineer on the old Innisfallen, which ploughed the waves from Cork to Fishguard. I clearly remember sailing with my older sisters Eugenia and Geraldine to visit the Corbridge family. Eugenia and I, giddy with the excitement of sailing at night, kept interrupting Geraldine, who stood outside our cabin being chatted up by a handsome young steward.

Truly momentous events will sometimes occur, unbidden, in an otherwise ordinary life. I have a vivid recollection of seeing John F. Kennedy in June 1963 as his motorcade swept past the top of our street. The entire neighbourhood had gathered on Patrick’s Hill to see the handsome American president and his tan. I distinctly remember being hooshed onto a low roof by some older friends, and from there onto a dormer window, then hoisted by my arms onto the roof of the Provincial Bank of Ireland, the perfect vantage point to witness history. Little did JFK, or the rest of us gathered on that hill, know the fate that awaited him in Dallas a few months later.

I still have a blurry recollection of the day he died. I can’t actually remember what I was doing or who else was in the kitchen, but I do remember my mam turned down the shop lights and pushed out the shop door. My dad turned up the wireless and looked worriedly from my mother to the wireless and back again. I wasn’t quite six yet, so I had no idea what this would mean for all of us. I was confused that someone would shoot such a nice man with his lovely smile, white teeth and American tan. It was as if the world had momentarily stopped turning and we had entered a vacuum, until Mam and Dad would try to make sense of it for us.

I’m roused from my reverie by the sound of my grandchildren coming back out to the garden to say goodbye. Loads of hugs and they’re gone. However, the encounter with my own inner child lingers. I realise the boy within has so much he really wants to say. Maybe I haven’t listened to him as much as he would have liked. Maybe nobody did, or could, for that matter. But the boy and myself have the rest of the day to ourselves, so we strike off for an amble along Bóithrín na Smaointe and back by Memory Lane.

At times, I take him by the hand, but mostly he’s running along beside me, talking nineteen to the dozen. As the Shandon bells reverberate and fade, we’re off … wandering the streets of 1960s Cork in search of adventure. Back to a time when my father could skip across a bog carrying three children in his arms. A time when my mother would suppress a giggle as she taught us to waltz around the kitchen with a sweeping brush – one-two-three, one-two-three. A time when this boy’s heart was as light as the wild winds that blow.

Where the Sacred Heart Is

‘Hiren the wireless!’

‘No! Don’t! Lowern it!’

‘Will ye get up?!’

Reveille in the Creedon household followed the exact same pattern every school morning. The bugle boy, my dad, was first up to attend to the overnight deliveries. He unlocked the shop door at 6 a.m., dragged in the crates of milk and bundles of newspapers, and turned the ‘Open’ sign to face the world. That sign only ever faced the other way for five hours a day.

Dad would switch on the kettle and the big radio set on either side of the gold-framed Sacred Heart picture in the kitchen and let them both warm up. Then he’d pop upstairs and give my mother a shout so that she could take over when he was gone to work. In between domestic duties, Dad would serve the first few customers, usually other dads rushing for the Ford and Dunlop factories down the docks.

At precisely 7.30 a.m., five sharp pips would emanate from the extension speaker on the third-floor landing. You see, apart from the wire at the back of the kitchen radio that served as an aerial, my father, an ingenious man, had attached yet another wire to the wireless, as it was curiously called. This cable was tacked discreetly beside the lino and rubber nosing cover on the steps of the stairs. It ran all the way to the speaker on the landing windowsill on the top floor outside my sisters’ bedrooms. The speaker was housed in its own little mahogany box with fancy holes at the front to let the sound out. It looked like it belonged on a church wall, but it sat on that windowsill for decades. The knob on the side said ‘Vol’ and there were two little lines: one read ‘Min’, the other read ‘Max’. But no matter how you twiddled it, the vol was always at max. And it worked – the Creedons always had a good school attendance record. Radio Éireann, above in Dublin, was now in on the act, calling the nation to rise up with ‘O’Donnell Abú’, aptly described as ‘a rousing march’. It certainly put the heart crossways in the two dozen souls sleeping under our roof.

It was a particularly big roof as it spanned two conjoined three-storey houses, each with its own shopfront. There was a small yard behind one house and a large extension behind the other. The extension was built by ‘Johnny the Builder’ when I was a toddler, and it provided extra bedrooms and two bathrooms. All told, there were only 12 bedrooms, so at times it could be a little cramped.

There was Mam and Dad and their 12 children. Norah, Carol Ann, Constance, Geraldine, Vourneen, Don, Rosaleen, Marie-Thérèse and Eugenia were all doing just grand until number 10 – Baby John – arrived in November 1958. They still call me Baby John. Miss Healy and Margaret O’Sullivan, who worked in the shop, also lived with us, as did Aunty Theresa and sometimes Aunty Martha, my mother’s sisters. There was also a menagerie of dogs, cats and, at various times, a budgie, a hen, a piglet, a pigeon with a broken wing, and a hedgehog my dad found outside the shop door one morning.

There was also room on the far side of the house for two bedsits, home to the most colourful characters my mother could source from the classified ads in the Cork Examiner. There was Joey Connors, an American journalist, who wrote for Time Life, amongst others. You could hear Joey click-clacking away on his typewriter all day and into the wee small hours. He was tiny and wore a little hat, and he chain-smoked Lucky Strike cigarettes, which my mother would order in to the shop especially for him. With or without his glasses, he squinted. It was like having our very own Mr Magoo, and I loved calling around to visit Joey’s bedsit. He wouldn’t stop smoking or click-clacking for anyone, but with a cigarette dangling from one corner of his lip and his neck craning forwards to examine his own words on the typing paper as it emerged from the roller, he’d tell me all about America, communists, Steinbeck, Kerouac, Elvis and Martin Luther King Jr. He could type and talk at the same time, so he fitted right in with the chatterbox Creedons. Joey died in 1970 while on his way to Shannon Airport to cover President Richard Nixon’s visit to Ireland.

Dr Nguryganda lived on the floor above Joey. He was from Kampala in Uganda, and he wasn’t really a doctor. He was actually a dentistry student at UCC, but my mother insisted we refer to him as Dr Nguryganda to give him ‘the ole boost’, as my father would call it. He was handsome, like a young Sidney Poitier, and he wore skinny suits.

I remember my mother asking him about racism. It was a new word for me, but I distinctly remember him saying that some people had been cruel to him when he was studying in England. He recalled bringing a bag of washing to his local laundrette in London when some woman told him he should throw himself into the washing machine too. My mother was mortified to hear such a thing and I was cross. He said Irish people stared at him, but had not been nasty to him … yet.

I might well have been the first. One day, three African nuns, who were probably also studying at UCC, called to our shop looking for Dr Nguryganda. I was told to bring them around to the side door that led up to the bedsits. I did, and then decided to spy on them. I watched that hall door all day, and the nuns never came out. By mid-afternoon, a horrific smell was coming from the bedsit. It was as if someone was boiling something that was gone off. It was clear to me that Dr Nguryganda was, in fact, a cannibal and that he had the three nuns tied together, boiling in a big pot. I tried telling my mother but she wouldn’t believe me, so I had no choice but to burst into the bedsit and check.

Using the tried and trusted elements of surprise and confusion, I swept the bedsit door open and was in like a one-man SWAT team, lobbing a verbal smoke-grenade ahead of me to confuse them, ‘Hello! Hello! Doctor Nguryganda, your Daily Telegraph has arrived below in the shop. Will I bring it up or will you …?’

There they were – Dr Nguryganda and the nuns chomping away at their dinner. For a little boy, this was a traumatic introduction to garlic.

Dr Nguryganda and myself went on to become great friends. At my mother’s insistence, I was his guide on a trip to Killarney, 60 miles away in County Kerry. I was only a small child and he was from Uganda, so neither of us knew the roads. However, we did manage to get the 6 miles to Blarney and back.

I was also his guest on a few trips to the Opera House to see the Cork comedy revue Summer Revels. I felt like royalty, with all those eyes following us as we crossed the plush carpet of the lobby of the theatre, me, my exotic guest, and our box of Maltesers. Panto dames Paddy Comerford and Billa O’Connell swaggered across the stage dressed as two old ladies from the city lanes having a right old barney. Billa, standing with his hands on his hips, whined, ‘C’mere, gurl. If I spots you lookin’ at my Tone-ee with dat guzz eye of yours again, I’ll break every bone in your corset!’ I wondered if Dr Nguryganda could make any sense of it, but he laughed in all the right places, so I think he enjoyed it.

Our shop, the Inchigeelagh Dairy, began as a retail outlet in the city for my grandfather’s butter and egg business in Inchigeelagh. My father’s Aunt Julia ran the shop on Devonshire Street until she retired and my father took over. Dad’s older brother and best friend, my Uncle John, took the reins from Grandad in Inchigeelagh and ran the family hotel, shop, post office and milling business with his wife, Gretta, and their 14 children.

Devonshire Street was one side of a city block. Most of the buildings were hundreds of years old and included all manner of shops, pubs, family homes, flats, a bank, a hotel and an undertaker’s. Just around the corner was McKenzie’s agricultural suppliers with its shuffling queue of horses, donkeys and carts.

Because there were so many churches and schools in the city centre, our streets seemed to be full of nuns and priests and Brothers. We knew all the uniforms: Capuchins from Holy Trinity wore brown habits, the Ursuline nuns wore black with big wimples, other nuns wore navy-blue, and the Dominicans from Pope’s Quay wore white robes with black outer garments. At the time, Ireland was producing huge numbers of both clergy and children. While the clergy concerned themselves with the rites of Rome, we children were more focused on the right to roam.

More often than not, we just took off and knocked on the front door of our latest best friend. If asked, I would simply tell my parents, ‘I’m goin’ out,’ and run for it. Despite dire warnings, I’d often go missing and spend the afternoon on a high stool in any one of a dozen pubs or betting offices nearby. I’d while away the hours drinking raza (raspberry cordial and water) or tea, listening to the old fellas talking about dogs, hurling and the price of the pint. I still love the company of old people, but as I grow older myself, there seems to be less and less of them.

On our street alone, we had Granda Carr, who fought in World War I; Mr McAuliffe, a steeplejack who knew no fear; Johnny the Congo, who fought in Africa with the UN; Ned Ring the blacksmith; the Drummer Boy, who sang at Covent Garden; and Louie Angelini, a Scottish bookmaker with an Italian name.

It was a colourful community. Up the street we had Armenian Christians, a Presbyterian church and a Baptist community. At one point, an American family of coeliacs moved into a rented house up the hill. My mother ordered special bread to the shop for them. I never knew their surname, but because everyone just referred to them as ‘the coeliacs’, I assumed they were a religious group like all the others.

Most adults were addressed as Mr or Mrs. Our shop assistant of 20 years was known as Miss Healy, which I believed to be her Christian name. For years, I just assumed her full name was Misshealy Creedon. I nearly fell out of my stand when she showed me a postcard she received. It was addressed to a Miss Brigid Healy, whoever she was. Really, you could not be up to adults.

I was gone all day and would only return home to regale my parents with mimicry and tales of the carry-on. Then, when they weren’t looking, I’d be gone again. The world was my oyster and Cork was my stage. It had a cast of thousands and a set made of open doors.

A Rogue Is Born

I greet you proud Iveleary’s sons and daughters fair and true.

Assembled at the South End Club old friendships to renew.

This annual opportunity I’m loth to let it pass.

Ere I recite a tale tonight on my Inchigeela Lass.

– Excerpt from ‘My Inchigeela Lass’, thought to be written by Seán Ó Tuathaigh and composed by Jim Cooney

On 18 March 1919, my father, Connie Patrick Creedon, crash-landed onto his parents’ bedroom floor. ‘I slid along the lino and when I finally came to a halt, I gathered my senses, had one good look around me, and with my two little arms aloft, I declared, “Inchigeelagh! Thank you, God! Thank you!”’

At least, that’s what he told me, anyway.

Unlike my dad, who witnessed his own birth in all its pain and elation, I cannot recall the day I landed at the Bon Secours hospital on College Road, Cork. I was told I was born on 4 November 1958, but I discovered recently that it was actually 3 November. Now, it may just have been a long labour, as I was huge. My sister Norah claims I was 12lbs at birth. Even in the new money that’s still 5.44kg: a fine-sized turkey or two healthy babies. I sometimes wonder if that’s it – maybe I’m actually a set of twins who never shut up.

But I do remember the day I first realised that my dad was 40 years older than me. It was the day of my Confirmation. I was 10, the youngest boy in the Confirmation class, and my father was dropping me off at the North cathedral. As he turned to leave, a schoolfriend’s dad spotted him and enquired, ‘How’ru, Connie?’

‘Erra, only average, Tommy. Cuíosach gan a bheithmaíteach, mar a dhearfá.’ (Average without being actually sick, as they say.)

‘Why? What’s wrong with you, old stock?’

‘Yerra, the usual. AND I hit the big five-oh today.’

‘Jaysus, are you fifty, Connie?’

‘I am, and ’tis downhill all the way to the grave from here on in.’

He was right, it was downhill all the way to the graveyard from the cathedral, but I had no idea before this moment that my dad was dying. I mean, we had been planning for my Confirmation, not his funeral. Yet there he was, hurrying away to die.

Inside, we lined up to get a clatter across the face from Bishop Connie Lucey. As we shuffled towards the front of the queue, I discreetly leaned towards my best friend, Tony Bullman, and whispered, ‘My father’s going to die!’

‘SHHH!’ spat a parent behind me.

Shortly afterwards, I got the clatter and became a strong and perfect Christian.

As it turns out, my dad did eventually die and we did carry him downhill all the way to his final resting place. However, that came a full 30 years later, when I was 40 and he was just a few weeks short of 80. Despite a little rust in the hips and ankles, my dad clocked up his fair share of miles in his fourscore years. He began, aged 15, driving Model TT Ford trucks for his father’s mill in Inchigeelagh, before becoming a bus driver for CIÉ in Cork City.

My grandfather, Cornelius Creedon, an industrious man, was a native Irish-speaker who left Oileán Eidhneach (Island of the Ivy)/Béal Átha an Ghaorthaidh (Mouth of the Stream in a Thorny Place) in the late 1800s and headed for Butte, Montana. He worked there as a copper miner before returning to Ireland with a bag of money to marry my grandmother, Norah Cotter, on 18 April 1912. Norah was the postmistress in the village of Inse Geimhleach (Inchigeelagh) on the eastern end of Loch Allua, where the lake narrows to become the River Lee again before picking up pace on its journey to Cork Harbour and out to sea. Within a few years, Con and Norah’s household included four sons, the village post office, a shop, a mill, some trucks and a small hotel in the village. The area was a breac-Gaeltacht (speckled Gaeltacht), where some households spoke Irish and others spoke English. Growing up behind the counter of the post office, my father, the youngest of the family, was fluent in both.

My dad always ate his food with relish – sometimes Yorkshire relish, other times just plain enthusiasm relish. I was often transfixed by a dimple on the side of his forehead that went in and out as his mandible chomped away on a pig’s head or a big bowl of tripe and drisheen that had been boiled in milk with a knob of butter. He would add a few taps of the small drum of Saxa white pepper that never strayed too far from our kitchen table. Having grown up in a hotel popular with English anglers, where pheasant, venison, wild trout and salmon were staples, my dad was a connoisseur. He often regaled us with the story of a less erudite guest at the hotel who, when offered ox tongue by the waitress, baulked at the idea and replied, ‘I couldn’t possibly eat something that came out of an animal’s mouth. I’ll just have an egg instead.’ Charming!

With the move to Cork City to attend secondary school, my father’s taste for the exotic deepened. Living with his Aunt Julia in the Inchigeelagh Dairy on Devonshire Street provided young Connie Pa with an opportunity to dive into the delights of the city centre. The streets of 1930s Cork bustled with trams and horse-drawn trailers laden with barrels of porter from Murphy’s Brewery, Thompson’s cakes, Hadji Bey’s Turkish delight, corned beef, spiced beef, offal, fresh coffee and blended teas … all produced within a few steps of our front door.

Connie Pa sucked the marrow out of life as if it were a leg of lamb. I can still see him with a tea towel flicked over one shoulder, hopping between serving customers in the shop and buttering mountains of brown bread for us, with the daily observation ‘I feed my men well!’ The tradition prevails. I never serve as much as a bowl of cereal to a guest without issuing the same salute to my own generosity.

Dad tipped the scales at 20 stone and he’d charm the birds from the trees. He was a swashbuckler, handsome and broad shouldered, a hurler, a hunter and a champion angler. As well as English and Irish, he spoke Classical Greek, Latin and Hainakatina, a language he created himself as a sort of shortcut to the word he was actually trying to think of. He would ask for a ‘coo-jack-a-swivvey’ as a generic term for the next tool he needed from the toolbox. If nature called while in company, he’d enquire if there was a ‘conswilly’ in the house. In a less affluent home, where the convenience might be outdoors, he’d probably ask for the ‘tinny shed’, the ‘fowl house’ or whatever other notion popped into his head.

A retired CIÉ man once told me about an occasion when some bus drivers were chatting as they finished up their shift for the day. It was Christmas week and they were in the locker room at Capwell bus garage on the south side of the city. Having handed in their takings and dockets through the hatch to the accounts clerk, the drivers were preparing for home. On the wall was a large wooden rack with rows of named pigeonholes, where a bunch of keys or an envelope could be left for a colleague. As they chatted, my father reached over and removed three envelopes from the box with ‘CP Creedon’ on the front.

The conversation continued as he opened the first of the envelopes. Inside was a Christmas card from a Mrs Barry, saying how grateful she was to my father ‘for keeping an eye on young Denis during the year when he was travelling to school on your bus’. There was a pound note inside the card. The second envelope had a ten-shilling note enclosed and the message wished him and his ‘fine big family the best of everything in the New Year’. The third envelope contained a large card and another pound note. This was from an ‘M. Heffernan’ in Blackrock and read, ‘Many thanks for stopping between the bus stops for me all year. I hope I didn’t get you fired! Happy Christmas and God bless you, Mr Creedon.’

‘Aren’t people wonderful?’ noted my dad. ‘All we are doing is our job and yet they still go to all this trouble and expense for us.’ He tucked the money and cards into his inside pocket and bade them farewell. ‘All the best, lads. Have a great old Christmas now, let ye. Good luck!’

‘I tell ya, that fella is some charmer,’ said one of the other drivers. ‘I mean, we all do our job the best we can, but you don’t see passengers sending us money in the post. I tell ya, Connie Pa is some beauty.’

My father waited until March before announcing to his colleagues that he had actually sent those three Christmas cards to himself.

While the lads were still trying to make sense of this revelation, he delivered the killer blow. ‘Of course, you do all know that envy is one of the seven deadly sins, don’t you?’ Game, set and match to Connie Pa yet again. He was a master of the practical joke. He wouldn’t think twice about sending an anonymous letter to his son-in-law as a prank or a sheet of sandpaper, complete with stamp, as a postcard to a grandchild. You couldn’t help but love him.

Poker or pranks, my old man knew how to play the long game. His hunches were good too. Many years ago he tipped Mick Mortell, a student in one of our bedsits, to become President of UCC (which he did), and our good friend Johnny Buckley, a student priest, to become Bishop of Cork and Ross (which he did). Then in 1993, a few years before he died, my father and I met the then Lord Mayor of Cork, Micheál Martin, at a function in City Hall. Micheál was with his dad, Paddy ‘Champ’ Martin, who was great old friends with my dad when they worked together at CIÉ. Dad took the opportunity to tell Champ that his son would someday become taoiseach. We all laughed our heads off when, in fact, we should have gone straight to the bookies – President of UCC, Bishop of Cork and Ross, and Taoiseach of Ireland would have been some treble. The lot of us could have gone off to Honolulu for the rest of our lives.

Still, a life on the road would always trump easy street for Connie Pa. He loved the people and stories that flowed through his day. It was all one big adventure. I remember being with him in the Westbury Hotel in Dublin a few months before he died. We were meeting up with my sister Marie-Thérèse and her family. At one stage I volunteered to accompany him to the ‘tinny shed’. As we were passing through the lobby, a young waitress stopped in her tracks to let him pass. He acknowledged her kindness with a wink and his usual ‘Good man, Julia’. She smiled back at him.

‘You’re an awful man,’ I chided.

‘Yerra, God help us,’ he tutted. ‘There’s no harm in me and I s’pose I haven’t too long to go now anyway.’

‘Are you sure now this time?’ I teased. ‘You’ve been telling me that you’re about to die for the last 40 years.’

‘Well, I am this time, and I’m ready to go too. No problem. There’s only one thing I’m worried about.’

‘And what’s that?’ I enquired.

‘I’m only worried that I might miss myself when I’m gone.’

I knew exactly what he meant. Although ready for the next life, he loved this life too. For all of the responsibilities that went with raising 12 children, Dad travelled light. It was life’s unfolding story rather than ‘things’ that interested him. He often reminded me that ‘there’s no pocket in a shroud’. For Connie Pa, it was all about the journey.

On the night he died, I did the maths. He was driving a Model TT Ford from the age of 15, then he moved on to buses for CIÉ, trucks for the road freight and back to driving buses again until he retired on his sixty-fifth birthday. Limerick was 120 miles return, a round trip to Dublin was 320 miles, even Ballybunion was 200 miles return, and the spin to my mother’s home in Adrigole was 140 miles there and back.

So, in his 50 years on the road, using the Cork– Limerick route as an average, he was driving 600 miles a week, giving an annual mileage of 31,200 miles. That would total 1,560,000 miles in his 50-year driving career.

Earth to the moon is 238,855 miles, or 477,710 miles return. In other words, my dad drove to the moon and back 3.2 times in his professional life. Add another couple of hundred thousand miles on the clock for a lifetime of private motoring with the family and we can conservatively estimate that he made four round trips to the moon from the day he was born to the day he died.

We know he crash-landed in Inchigeelagh in 1919, but I trust my man on the moon had a soft landing on his final return.

Gentle as the Fawn

She was modest as the cooing dove and gentle as the fawn

That roam over Desmond’s storied heights,

those highlands o’er Gougane

No goddess fair in Grecian days in beauty could surpass

My winsome rogue, my Máirín Óg, my Inchigeelagh Lass.

– Excerpt from ‘My Inchigeela Lass’, thought to be written by Seán Ó Tuathaigh and composed by Jim Cooney

Both of my parents were born into an Ireland still ruled by Britain. My mother was two years younger than my father. She was born on 1 October 1921, a full 14 months before the 26 counties became the Irish Free State and almost three decades before they became the Republic of Ireland.

Life is never simple and neither are parents. My father was a talker; my mother was a listener. They loved each other dearly. While both my parents bemoaned the fact that the island of Ireland had been divided, they had no dislike of England. They listened to the BBC World Service on our big old radiogram in the kitchen and loved to see the Irish do well in Blighty. Singer Val Doonican and female impersonator Danny La Rue were huge stars in Britain and a source of great pride at home.

The musical repertoire in our car was led by my dad and included show songs such as Paul Robeson’s ‘Ol’ Man River’ alongside popular songs in the Irish language, sean-nós and light opera. Ballads of the 1916 Rising like ‘The Tri-Coloured Ribbon’ and ‘The Foggy Dew’ sat side by side with ‘The Laughing Policeman’ and classics from Gilbert and Sullivan’s HMS Pinafore. The carload of Creedons would be in stitches at Dad’s hilarious rendition of ‘Barnacle Bill the Sailor’ from the English music-hall tradition, where my father performed both parts: the big bass-baritone voice of Barnacle Bill the sailor and the falsetto of the fair young maiden. Whenever my father sang a verse from ‘My Inchigeela Lass’, especially the part about the cooing dove and the gentle fawn, I always felt like he was addressing my mother. He would have passed through that stunning landscape around Gougane on his way from Inchigeelagh back to visit my mother’s home when they were courting.

Only once ever do I remember my father persuading my mother to sing. We were travelling west to Beara in the car and were taking it in turns to contribute to the sing-song. Rosaleen and Marie-Thérèse harmonised beautifully as they sang ‘Frère Jacques’, which they learned in school from the Ursuline nuns at St Angela’s. Eugenia and myself belted out our usual party piece, the bawdy Dublin street ballad ‘The German Clockwinder’. Eventually, after much persuading from my dad and loads of pleading from us, Mam agreed to try a song. She virtually whispered a beautifully shy performance of ‘Bantry Bay’. When she ran out of words and said, ‘That’s all I have of it,’ my father declared, ‘This is not a singsong any longer, children. What we are now witnessing is a recital! Well done, Siobhán!’ We all cheered for her.

At various stages my mother was known by Hannah Maria Blake, which was her birth name; Joan, which some of her older friends called her; and Siobhán, as she called herself. I always called her Mammy.

Well, not always. Once I secured the right to roam, aged about six, I took to calling her Mam, an abbreviation favoured by the rest of the gang. I mean, you can’t be threatening all-out war on the Dominick Street gang and still be calling your mother ‘Mammy’.

My mother was the seventh sister of 10 girls born to William and Kate Blake of Crooha, Adrigole, on the stunningly beautiful Beara Peninsula. Beara, like its people, is both lush and durable. Like a finger pointing defiantly at the Atlantic Ocean, it faces the prevailing weather from the south-west and absorbs more sunshine and showers than most.

My mother loved her home place and spoke with great tenderness of her parents and the games of dress-up and make-believe she shared with her nine sisters. Although high on a hill, the Blake farmstead was protected from the bitterness of the north wind by the peninsula’s ridge behind it. Their lofty aspect afforded them expansive views southwards across Bantry Bay and westwards along the peaks and valleys that ripple all the way to the ocean. Unlike the clamorous city streets of my childhood, my mother’s memories of home were painted in a blur of watercolour brush strokes. Lush hedgerows of emerald fern with clusters of lemon-coloured primrose at its feet; swathes of saffron-orange montbretia and blobs of blood-red wild roses entwined in the burgundy fuchsia that went on for ever. Everything seemed so gentle: the neighbours, the collie, the cattle.

But underneath Beara’s flourishing surface lay a harsh bedrock – reality. Bad land, big families and British rule led to incredible hardship and the inevitability of emigration. My great-grandfather Edmund Blake was born to John and Margaret Blake on 1 April 1844 and would have been just a baby, taking his first steps, as the shadow of famine crept up Hungry Hill. My grandfather, William Blake, was born in 1883. Unlike his namesake, the English poet, our grandfather knew real hardship. The post-famine years saw a trail of tears pouring down Beara’s slopes and away to America. Somehow, William maintained his grip on the rock. However, all but two of his children were to leave Adrigole. In 1930, when my mother was aged 8, her older sisters Maura and Elizabeth, both aged 17, sailed for America. Maura eventually became a nurse and Betty went her own way, returning to Ireland just once when I was about 10.

My mother loved the pastoral poems of Padraic Colum, such as ‘A Cradle Song’ and ‘An Old Woman of the Roads’. As a young girl, she read and reread Ulrick the Ready, a historical novel set in Ireland during the 1600s. It was written by Beara’s literary giant Standish O’Grady.