An Unsettled Nation: Moldova in the Geopolitics of Russia, Romania, and Ukraine E-Book

Eduard Baidaus

38,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: ibidem

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Serie: Soviet and Post-Soviet Politics and Society

- Sprache: Englisch

This book investigates state-building, distorted identities, and separatism in the Republic of Moldova. It presents research on the historical preconditions and spread of the secessionist movement in Transnistria, the war in the Dniester River valley, and the diplomatic deadlock of the Transnistrian problem. It examines the conflicting positions that political parties, the public, and experts have taken towards the problems that challenge the nation- and state-building processes in this post-Soviet state. Additional focal points include the reassertion of Russia’s power in the post-Soviet space, Ukraine’s effort to become a major political player in the region, and Romania’s attempt to retrieve its influence in Moldova. This study demonstrates that separatism generates mutually exclusive nation-building projects on the territory of a single state, that international actors play a significant role in this process, and that domestic and external factors hinder the development of a resolution of the so-called "frozen conflict" over Transnistria. Honorable Mention, 2024 Taylor and Francis Book Prize in Slavic, East European, and Eurasian Studies, Canadian Association of Slavists.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 1021

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Ähnliche

To my parents and my family

Contents

Foreword

Preface

Acknowledgments

Abbreviations

Introduction Theoretical Framework: Nation-Building and Separatism

The Historical Context

Nationalism and Separatism: Linking the Imperial and Soviet Past with the Present

Objectives, Research Questions, and Working Assumptions

Prior Research: Historiography and Geopolitics

Materials and Methodology

Archives, Published Documents, and other Materials

Interviewees and Interviews

The Thematic Structure and the Chronological Framework

A Note on Transliteration

Language and Terminology

I. Moldova and Transnistria Historical Background and Political Roots, 1917–1985

I.1. Moldova: Past Domestic and Foreign State-Building Projects

I.1.1. A Bessarabian Project that Failed: The Moldavian Democratic Republic

I.1.2. The MASSR: The Second Moldavian Republic

I.1.3. “Sunny Moldavia”: From Foundation to Perestroika

I.2. Nation-Building: Challenges of Divisive Cultural and Identity Politics

I.2.1. Imperial Russia’s Moldavians: The Impeding of Making Romanians

I.2.2. From Moldavians into Romanians: Instilling a New National Consciousness

I.2.3. The Making of Interwar Soviet Moldavians in the MASSR

I.2.4. United and Merged: The Making of Soviet Moldavians in the MSSR

II. Perestroika, Nationalism and Internationalism in “Sunny Moldavia,” 1985–1991

II.1. On the Eve: “Sunny Moldavia” Prior to Perestroika

II.2. “We Are Romanians!”: The National Awakening of Soviet Moldavians

II.2.1. The Nationalist Framework and the Fight for Language Legislation

II.2.2. Perestroika, Glasnost, and Pan-Romanian Mobilization

II.3. Russian speakers in Soviet Moldavia: “Suitcase, Train Station, Russia!”

II.3.1. Becoming Domestic Outsiders: “Sunny Moldavia’s” “Russians”

II.3.2. The Counter-Mobilization and the Struggle for the Russian Language

II.3.3. Separatism at the “Gates”: The Warning Signs

II.4. Toward the Break: The Moldavian SSR, September 1989–December 1991

II.4.1. Unfolding Separatism, Romanian Symbols, and “The Bridges of Flowers”

II.4.2. Soviet Moldavia: Disintegration, Separation, and Independence

III. Damaged Peace: Preconditions That Heralded the Transnistrian War, 1989–1991

III.1 Transnistria: The Legitimization of Separatism and Justification of Self-Defense

III.2 Moldova: Failed Attempts to Preserve Political Unity and Territorial Integrity

III.3. Sliding Toward War: Pre-War Violence

IV. The Heat before the “Freeze”: The Transnistrian War, 1992

IV.1. Moldova’s Fighters: Duty, Patriotism, Fear, and Solidarity

IV.2. “This Was My War!” Defending Transnistria: Romania-phobia and Slavic Brotherhood

IV.3. The Involvement of Romania, Russia, and Ukraine

IV.3.1. Romania

IV.3.2. Russia

IV.3.3. Ukraine

IV.4. The Course of the War: Combat Actions and Wartime Diplomacy, 2 March–21 July 1992

IV.4.1. The Outbreak of War

IV.4.2. The War and Wartime Diplomacy

V. Separatism in Postwar Moldova: International Aspects, 1993–2013

V.1. The Impact and Geopolitical Consequences of the War

V.2 The Transnistrian Diplomatic Deadlock

V.2.1. Preconditions to the Failure of Negotiations

V.2.2. Postwar Diplomacy and the Stalling of Negotiations

V.3. Impediments to Reconciliation

V.3.1. The Cold War Relationship between Transnistria and Moldova

V.3.2. Russia’s Questionable Commitment to Moldova

V.3.3. Moldo-Romanian Unionism

V.3.4. Relations between Moldova and Ukraine

V.4. Failed Foreign Reconciliation Projects

V.4.1. The OSCE Mission in the Republic of Moldova

V.4.2. Russia’s Plans for a Settlement

V.4.3. Ukraine’s Yushchenko Plan

VI. The Nature of the Transnistrian Conflict and the Prospects of Its Resolution, 1993–2013

VI.1. Defining the ‘Frozen Conflict’ in the Republic of Moldova

VI.1.1. Views from the West

VI.1.2. Views from Romania

VI.1.3. Views from Ukraine

VI.1.4. Views from Russia

VI.1.5. “Protracted” rather than “Frozen”

VI.2. Assessing the International Input on the Transnistrian Problem

VI.2.1. Views from Russia

VI.2.2. Views from Ukraine

VI.2.3. Views from the West

VI.2.4. Views from Romania

VI.3. Expert Views on the Solutions and Prospects of Separatism

VI.3.1. Views from the West

VI.3.2. Views from Ukraine

VI.3.3. Views from Romania

VI.3.4. Views from Russia

VII. The Domestic Discourse on the Transnistrian Problem, 1993–2013

VII.1. Political Parties and Developments

VII.2. Divergent Views of History

VII.2.1. The Interpretation of the Past

VII.2.2. The Characterization of the Present

VII.2.3. Imagining the Future

VII.3. The Transnistrian Problem in Political Platforms

VII.3.1. Conflicting Approaches to Settling the Dispute

VII.3.2. Reality vs. Political Platforms

VII.4. Civil Society Organizations and the Issue of Transnistria

VII.4.1. The December 2012 Memorandum: The Purpose and Content

VII.4.2. The December 2012 Memorandum: Impact and Assessments

VII.4.3. Positions of Other Moldovan and Transnistrian NGOs

VII.5. Assessments of a Political Fiasco: The Unproductive Contribution

VII.5.1. Chisinau and Tiraspol Government Officials

VII.5.2. Domestic Civil Society Experts

VII.5.3. Accredited International Experts

VII.5.4. The Opinions of the General Public

VIII. Separatism and Nation-Building: Education and the Forging of Conflicting Identities, 1991–2013

VIII.1. Power of the Primers: Imagining the “Motherland,” Constructing Identities

VIII.1.1. The Predecessors: Soviet Primers

VIII.1.2. The Successors: Post-Soviet Primers in Moldova and Transnistria

VIII.1.3. Between Ethnocentric Nationalism and Civic Identity

VIII.2. The Stumbling of Reconciliation: Disruptive History Teaching

VIII.2.1. History Education in Moldova

VIII.2.2. History Education in Transnistria

VIII.3. History Narratives in Moldovan and Transnistrian Textbooks

VIII.3.1. Imperial Russia: Territorial Acquisitions and Nation-Building

VIII.3.2. Romanian Bessarabia and the MASSR between the World Wars

VIII.3.3. The Second World War, the Great Patriotic War, and the Holocaust

VIII.3.4. Postwar Recovery, Perestroika, and the Rise of Nationalism

VIII.3.5. Soviet Collapse, the Transnistrian War, and Bloody Separation

IX. Nation-Building and National Identity: Political Symbolism and Nationality Policies, 1989–2013

IX.1. National Symbols: Unity vs. Division

IX.1.1. Between Soviet Legacy and National Heritage: Flags, Coat of Arms, and Anthems

IX.1.2. National Symbols: Perceptions and Attitudes

IX.2. Holidays for Nation-Building?

IX.3. Identity in Politics and Nationality Policies

IX.3.1. Identity: Constitution vs. Reality

IX.3.2. The Issue of Ethnic Identities and the Authorities‘ Nationality Policies

IX.3.3. The Problem of Identities in the Platforms of Political Parties

IX.4. Unsettled Identities and Self-Identification: “Amphibians,” “Budweisers,” or Undefined?

Conclusion

Appendices

Appendix 1. Interviews

1.1. Project description and consent form for interviews

1.2. Interview Questions. Group I.

1.3. Interview Questions. Group II.

1.4. List of Respondents

1.4.1. Moldova. Group I.

1.4.2. Moldova. Group II.

1.4.3. Transnistria. Group I.

1.4.4. Transnistria. Group II.

1.4.5. Romania. Group I.

1.4.6. Russia. Group I.

1.4.7. Ukraine. Group I.

1.4.8. The EU, the OSCE, and Germany

Appendix 2. Political Parties and Organizations.

Table 1. Moldova. Active political parties and organizations

Table 2. Transnistria. Active political parties and organizations

Table 3. The representation of the Moldovan political parties in Parliament after elections.

Table 4. The representation of the Transnistrian political parties in the Parliament of the TMR after elections.

Table 5. The priority placed by the Moldovan parties on “Transnistria,” “Foreign Policy,” and “National Security” in their political platforms.

Table 6. The priority placed by the Transnistrian parties on “Transnistria,” “Foreign Policy,” and “National Security” in their political platforms.

Table 7. The position of sections on the Transnistrian problem within the platforms of Chisinau-based political parties.

PNŢ

Table 8. Moldova. Types of approaches to the Transnistrian problem articulated in the platforms of political parties.

Table 9. Transnistria. Types of approaches to the Transnistrian problem articulated in the platforms of political parties.

Table 10. Frequency of the Declarations regarding “Transnistria” “Foreign Policy/EU Integration”, and “National Security” made by the Moldovan political parties between 2002-2012.

Table 11. Annual frequency of Declarations regarding “Transnistria” “Foreign Policy/EU Integration”, and “National Security” made by the Moldovan political parties between 2002-2012.

Table 12. Frequency of Declarations regarding the Transnistrian problem made by the Moldovan political parties between 2002-2012.

Appendix 3. List of the given names.

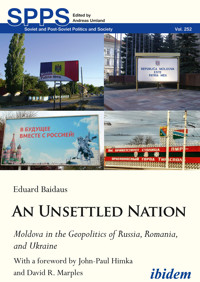

Appendix 4. Images

4.1. Billboards. Moldova (All in Romanian only)

4.1.1. “Love Your Language! Love Your Country!”

4.1.2. “Moldova—My Motherland.”

4.1.3. “The Republic of Moldova Is My Motherland.”

4.1.4. “The Republic of Moldova Is My Motherland.”

4.2. Billboards. Transnistria (In two languages)

4.2.1. “The Motherland Is Not For Sell!” (in Russian)

4.2.2. “The Republic Is Not For Sale!” (in Cyrillic Romanian [Moldovan])

Bibliography

Archival Sources

Published Primary Sources

Published Memoirs, Testimonies, and Recollections

Newspapers and Magazines

Books

Dissertations

Secondary Sources

Textbooks

Articles

Book Reviews

Unpublished Communications

Internet Sources

Interviews and Videos

Documents and Primary Sources

Articles

Map 1: Central and Eastern Europe, Map No. 3877

Rev. 8, August 2016, UNITED NATIONS

Map 2: Republic of Moldova, Map No. 3759

Rev. 5, February 2013, UNITED NATIONS

Map 3: The Principality of Moldavia in the 15th–18th Centuries.

Reproduced, with permission, from the Internet Encyclopedia of Ukraine (www.encyclopediaofukraine.com).

Map 4: Eastern Europe ca. 1650.

Reproduced, with permission, from Mykhailo Hrushevsky, History of Ukraine-Rus’, Vol. 10: The Cossack Age, 1657–1659 (CIUS Press 2014) (ciuspress.com).

Map 5: Ukrainian National Republic [Ukrainian People’s Republic], 1917–1921. Reproduced, with permission, from the Internet Encyclopedia of Ukraine (www.encyclopediaofukraine.com).

Map 6: Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic, 1919–1991. Reproduced, with permission, from the Internet Encyclopedia of Ukraine (www.encyclopediaofukraine.com).

Map 7: Ethnic composition of Soviet Moldavia.

Reproduced, with permission, from the Internet Encyclopedia of Ukraine (www.encyclopediaofukraine.com).

Foreword

John-Paul Himka and David R. Marples

Moldova is a small country, slightly larger than Belgium and slightly smaller than Taiwan; it has a population somewhat larger than that of any of the three Baltic States and is roughly equal to that of Utah (in the USA). It is essentially landlocked, except for a single port on the Danube, which can take in vessels from the Black Sea. Although the Soviets liked to call it “Sunny Moldavia,” it is sunny primarily by comparison to Moscow; Chisinau does not enjoy as much sunshine as, say, Rome or Madrid. And, as the excellent text that follows makes clear, it is still Moscow, not Europe, that makes the weather in Moldova.

In this book Eduard Baidaus analyses post-Soviet Moldova, and its breakaway republic of Transnistria, at a depth not hitherto achieved, but certainly warranted. He uses a large manifold of sources—the press in several languages, interviews and surveys, the programs of political parties, schoolbooks, archival documents, memoirs, and books and articles in English, Romanian, Russian, and Ukrainian. He examines his subject from many different angles and from the viewpoint of multiple stakeholders in the ongoing crisis that is called Moldova.

It is useful to think of east-central European political geography as a palimpsest. Differences in contemporary political cultures often reflect an underlayer of old borders. It makes a difference whether a particular region was part of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth or the Russian Empire, of the Ottoman Empire or Habsburg monarchy, or—as is really very common—of different polities over time, as states expanded, contracted, or were partitioned. In the case under examination in this monograph, the most relevant buried border is that produced by World War II and its aftermath.

As a result of its alliance with Nazi Germany in 1939, the Soviet Union acquired new territories to the west, and the border between the old Soviet territories and the new ones remains salient in several cases. Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia were incorporated into the USSR in 1940. Today these states are the only post-Soviet countries that have been accepted into NATO and the EU. In 1939, the Soviets took the Ukrainian-inhabited regions of Galicia and Volhynia from dismembered Poland. And in every post-independence election, these regions of Ukraine have voted differently from the rest of the country; there are also religious, linguistic, cultural, and memory issues that differentiate these regions from the rest of Ukraine. Moldova also has a cleavage along the same border. Most of Moldova was acquired by the USSR from Romania in 1940, but part of it, on the left bank of Dniester, had been a part of the Soviet state from the beginning. It is this latter part that formed the basis of Transnistria, the breakaway republic that made war with the rest of Moldova and remains a wound in the Moldovan polity and society to this day. The unpacking of the latter sentence is what this book is about.

The continuing power of the World War II border suggests some interesting points. One is that it helps explain the continuity of Russian policies in the region even when different leaders have been at the helm in Moscow. As Eduard was handing in the chapters of the dissertation on which this book is based, major events were unfolding in Moldova’s neighbor, Ukraine—the Euromaidan, the invasion and annexation of Crimea by Russia, the “Russian Spring,” and the outbreak of war in eastern Donbas. What struck us as we were reading Eduard’s texts against the background of the Russian intervention was all the similarities between what happened in Moldova in the early 1990s and the history unfolding in Ukraine in the mid-2010s. Russian tactics and policies were strikingly similar, and even some of the same military personnel were involved in both cases. Yet, in the Moldovan conflict, Boris Yeltsin—the politician who had shortly before dissolved the Soviet Union—headed the Russian state, and in the Ukrainian conflict, it was Vladimir Putin.

The similarities in policy and tactics indicate that, aside from the political ideas of individual leaders, structural reasons have to be taken into account in order to understand what was happening. One of these is clearly the division between old-Soviet Moldova and Moldova that was incorporated into the Soviet Union after World War II. Different former Soviet borders have also been a major factor in other post-Soviet conflict situations, notably the invasion of Crimea in 2014 and the wars over Nagorno-Karabakh, most recently in 2020.

The division between the two Moldovas also indicates how important the interwar period was for shaping political cultures. The bulk of what is Moldova today spent the interwar period within Romania, a state that espoused nationalism and a unified Romanian identity. But breakaway Transnistria was originally forged under the direction of the ‘Man of Steel.’ Stalin wanted to create a new Soviet man and managed to succeed in producing many copies of the homo sovieticus. It must be these differing experiences, lasting only two decades, that created such different political cultures in what later became our contemporary state of Moldova. Although all of Moldova had spent fifty years together in the Soviet Union before the land became independent, it was not enough to erase the distinct political cultures.

The fifty years was enough, however, to disperse Russophones throughout the new territories acquired as a result of the Nazi-Soviet Pact and World War II. Jobs in the communist and state apparatus brought Russians into these territories, and sometimes the dispersion of Russians and Russophones was a direct result of Soviet population policy. Russians account for a quarter of the population of Latvia and Estonia. Russophones still make up about 20 percent of the population of Lviv, the city considered to be the bastion of Ukrainian nationalism. In Moldova, about 15 percent of the population uses Russian for everyday communication. Language spoken does not directly translate into particular political opinions. However, Russophones read, listen to, and watch—in addition to local Russian-language media—media produced in Russia, media that advocate pro-Russian political and geopolitical positions. To some extent, these Russophones are like the Pieds-Noirs of revolutionary Algeria, and the Russian state understands them to be a form of geopolitical capital.

But what interest would Russia have in little Moldova, some seven hundred miles west of the current Russian border? The answer has little to do with the sunshine in the republic, and more to do with its strategic location. During the Russian Spring in Ukraine, Putin advanced the idea of “Novorossiya,” a territory carved out of Southern Ukraine that would connect Russia with the Crimean Peninsula and beyond, to the border of Transnistria. Ukraine would have been deprived of a sea coast and reduced drastically in size. Both Ukraine and Moldova would be demoted to client states. After all, how could Moldova stand up for itself against a neighbor like Russia, boasting a population over forty times as large, a GDP over a hundred times as large, and a land mass close to five hundred times as large? The Novorossiya project would have given Russia access to the mouth of the Danube and also closer to that long-time lodestar of Russian geopolitics, the Bosphorus.

As we write, relations between Russia and the West are at a low point, and they make no secret of being geopolitical rivals. There are many pro-Western Moldovans and Ukrainians who look to North America and the European Union to help them withstand Putin’s neoimperialist designs. But there are no pro-Moldovan forces in the West, and the USA and Canada are the only Western countries that can be characterized as, to a certain extent, pro-Ukrainian. From the perspective of the European Union, both countries are solidly in the Russian sphere of influence, as is Belarus. Membership in the European Union is not on offer to any of these countries. The EU offers verbal support of movements championing Western values in these countries, but it does not want to sour relations with resource-rich Russia any further.

At the start of 2022, the situation in Russia’s ‘Near Abroad’ appeared to be reaching a crisis point. One report suggested that there was a Russian plan to stage provocations in eastern Ukraine as a premise for a Russian invasion. Over 100,000 Russian troops had massed behind the border, equipped with modern tanks and missiles. Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov issued an ultimatum that NATO must state unequivocally that Ukraine would never be admitted as a member. He expressed his anger that there had been no response to the Russian terms and that the Russian leadership “would not wait forever.” Similar reports were coming out of Georgia, and also Moldova. The effrontery of such an ultimatum notwithstanding, it offers an indication of how important these territories remain to the current Russian government.

In 2021, the geographical region that Russia sought to control was facing a new phenomenon, namely a refugee crisis that was clearly initiated in one of Vladimir Putin’s dominions, namely Belarus, still under the de facto leadership of Aliaksandr Lukashenka, despite his failure to win the presidential election held on August 9, 2020. Having repressed several mass protests, Lukashenka has in a very real sense become Putin’s vassal. Dependent on Russian support with military aid and even national media, as well as large-scale loans, Lukashenka announced his decision to allow would-be migrants to come to Belarus with short-term visas and migrate to the EU through the border with Poland. A human crisis was created when the Poles refused admission for the migrants to enter and sent 10,000 troops to guard their border, leaving many Kurds, Iraqis, and others to roam the Belavezha forest for weeks in search of food.

This book is a clearly written and incisive analysis of the nature of the ‘Russian World’ that relies not only on brute force but also propaganda and hybrid warfare disseminated through social media. Russia has several advantages. First of all, all the involved countries were formerly part of the Soviet Union until 1991. Second, except for Ukraine, they can be categorized as small states, and third, they depend to a greater or lesser extent economically on the Russian resources of oil and gas. Lastly, as the wars in Moldova, Georgia, and Ukraine between 1992 and 2015 demonstrate, the governments are very much at the mercy of the Russian Army if they are unable to reach an agreement with Moscow. In December 2021, before his summit with Putin, US president Joe Biden affirmed that the United States would not aid Ukraine if the Russians cross the border. Ukraine, Moldova, and Georgia are not members of NATO.

Though it has not offered membership, the European Union is interested in the future of these states and has been prepared to cooperate with them since 2009 through the Eastern Partnership project (EP), which also includes Armenia and Azerbaijan, two countries that continue to cross swords over the status of Nagorno-Karabakh. Potentially, at least five of the six EP members could apply at some point for EU membership—Belarus is probably too close to Russia for such an application to be realistic. It was the promise of Association Membership in the EU and the refusal of then Ukraine president Viktor Yanukovych to sign it that brought Ukrainians to the Maidan in the center of Kyiv in November 2013. Moldova is a very complex case since it is also linked closely with Romania, as this book shows. Romania was accepted as an EU member in 2005 with formal membership starting on January 1, 2007. In 2020, Moldova elected a pro-European president Maia Sandu. Just a year later, it finds itself in an energy crisis, with a 65.8 million Euro debt to Russia’s Gazprom and price hikes that threaten to cause national upheaval. The crisis once again illustrates Russian leverage through energy resources.

But what are the Russian goals in the region it considers its neighborhood and legitimate area of control? To what sort of future can “Sunny Moldova” aspire? Its breakaway region, Transnistria has been ‘independent’ from Moldova for more than three decades. It is not recognized by a single UN member, and two of the three countries that recognize it (South Ossetia and Abkhazia) are themselves breakaway states from Georgia that also lack international validity. The other is Artsakh, formerly the Republic of Nagorno-Karabakh, the Armenian enclave inside Azerbaijan. Transnistria is a territory that exists through Russian collusion and support but Russia has not sought outright incorporation, just as it has not sought to annex South Ossetia or the breakaway regions of the Donbas. Thus, the truculence often displayed by Putin coexists with caution and limited goals.

On the other hand, as Eduard Baidaus shows, there are limits to what can be achieved through negotiations. Russia has undermined the stability of the EU states, it has used energy resources as a weapon, and it has resorted to outright threats when faced with the expressed wishes of these states to seek the defensive security of NATO membership. Thus, the future of Moldova depends very much on two factors.

First of all, the leadership of Vladimir Putin in Russia will not last forever. The anti-Western rhetoric emanating from Moscow and Russia’s focus on both its military and mercenaries to intimidate its neighbors is of relatively recent origin. Between 1992–1995, after Russia became independent, Foreign Minister Andrei Kozyrev attempted to orient the country toward the West. Even in 2001, just a year into the Putin presidency, there were signs of US-Russian cooperation in the fight against terrorism following the 9/11 attacks on New York and Washington. Putin made comparisons with Russia’s war in Chechnya and embraced a common enemy: militant Islam. The current impasse dates back to 2008 with the war in Georgia and the severing of relations with Ukrainian president Viktor Yushchenko (under the 2008–2012 presidency of Dmitry Medvedev in Russia). The 2013–2014 Euromaidan in Ukraine that removed a pro-Russian president was a culmination point. The Russian leadership perceived the uprising as Western-initiated and funded and as one of a series of “color revolutions” that would eventually be expanded to Russia.

Since then, the position of the Russian leaders has become increasingly entrenched and obdurate. The hard-line position extends beyond politics: indeed Putin, Lavrov, and others appear to regard the entire democratic West as degenerate and weak, from “Gay Evropa” to Donald J. Trump, Me Too, and Black riots. The practice is to probe constantly for weaknesses in the armor of democracy while espousing bold and angry narratives about NATO expansion into traditional Russian enclaves and announcing red lines that cannot be crossed.

But herein also lies a concealed weakness: Russia is not an economic power. It is a military state with a relatively small economic base and is run by a near-dictator and his security forces are backed by powerful oligarchs. Moreover, the Russian economy is heavily dependent on nonrenewable oil and gas. Living standards outside the two major cities are low. The ruble plummets every time there is an international crisis, and an invasion, say, of Ukraine would likely result not only in another currency fall, but also in a bloody conflict, thousands of casualties, and deeper Western sanctions that would destroy any possibility of economic growth. The world is global, and no state is autarkic. Russia depends on exports of energy to Europe, particularly Germany, its closest partner. It cannot isolate itself from economic partners and the EU is vastly superior to the Russian Federation as an economic power. In short, it is weaker than it appears.

For any authoritarian leader, a key area of concern is an exit strategy, yet Vladimir Putin does not appear to have one. Instead, he has amended the Russian Constitution so that his potential term expires only in 2036 when he would be 83 years of age. It is unlikely that he will remain for so long. We have seen major anti-Putin protests in 2012 and 2020, and mass protests in both Belarus and Kazakhstan between 2020 and 2022 against long-standing leaders who are close to Putin. But the possibility of a more democratic leadership also seems remote, so one cannot anticipate major changes in the approach to the neighborhood.

The future of Moldova therefore will be dependent on its actions and the response of the United States and European Union to Russian aggression. A viable response may require recognition of the reality: Russia is no longer a Great Power and relies heavily on threats, bluster, and media propaganda to create an image of a regional colossus that has legitimate concerns in independent states of the former Soviet Union.

Edmonton, Alberta, Canada

January 19, 2022

Preface

The separation of the Crimean Peninsula in 2014 and the ongoing war in Ukraine have sparked tremendous interest in the subject of pro-Russian separatism for scholars investigating international relations and nation-building. These events and the internationalized conflict in Ukraine in the post-Soviet space, however, are not a novelty. Strong separatist movements of ethnic minorities emerged during the dissolution of the USSR in several Soviet republics such as Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia, and Moldova.

This book investigates state-building, distorted identities, and separatism in the Republic of Moldova. At various times, this region was a former imperial Russia borderland, a province in interwar Romania, a republic in the Soviet Union, and ultimately a modern state where the interests of Moscow and the West collide. Similar to Ukraine, Moldova is a transitional zone between Europe and Eurasia, a country that faces the challenges of a post-communist society and represents a microcosm of mixed ethnic, cultural, and political identities.

The book presents research on the historical preconditions and spread of the secessionist movement in Transnistria, the 1992 war in the DniesterRivervalley, and the diplomatic deadlock of the Transnistrian problem. It further examines the conflicting positions that political parties, the public, and experts have taken regarding the problems that challenge the nation- and state-building processes in this post-Soviet state. Additional focal points include the reassertion of Russia's power in the post-Soviet space, Ukraine's effort to become a major political player in the region, and Romania's attempt to retrieve its influence in Moldova.

This study demonstrates that separatism generates mutually exclusive nation-building projects on the territory of a single state, where pre-existing historical conditions and geopolitical realities interweave and impede the construction of a modern nation-state. It also evinces that international actors play a significant role in this process and that they are dominant and superimposed on the local decision-makers. Moreover, domestic and external factors connected with nation-building policies often conflict with each other and hinder the development of resolution of the so-called ‘frozen conflict’ over Transnistria.

Acknowledgments

Many people and institutions helped me while I was working on this monograph. I am glad that I have reached this stage, and I would like to take the opportunity to thank everyone involved in the preparation and publication of this book. The idea for this work goes back to 2006 when I immigrated to Canada and met Frank E. Sysyn upon my arrival here. Following his encouragement and support from my family, I applied for Ph.D. study and was fortunate to be accepted at the University of Alberta in Edmonton. In essence, this work has leveraged my pre-emigration academic and life experiences as well as the challenging yet rewarding years of doctoral pursuit at the University of Alberta, taking shape in my dissertation and this book.

First and foremost, I owe an enormous debt of gratitude to Professors John-Paul Himka and David R. Marples from the University of Alberta. Their substantial and continuous guidance as academic supervisors enabled me to acquire a deep understanding of the history and current transformations in post-communist Europe. I have enormously benefited from their mentorship and inspiration as well as from their comments on my scholarly writing for years, while in the Ph.D. program and after graduation. The unstinting support they provided me with, starting with the initial phase of my doctoral research and ending with this book’s final draft, make me feel profoundly indebted to both of them.

I am deeply grateful to my Canadian colleagues, Serge Cipko, Heather J. Coleman, Stéphane-D. Perreault, Per Anders Rudling, Marko R. Stech, Mykola Soroka, Frances Swyripa, Jeff Wigelsworth, and Serhy Yekelchyk for their support at different stages of my work on this book. Wade Matkae’s input was also important to me. His experience as a UN Peacekeeper in Bosnia in the 1990s and his critical reading of my chapter about the Transnistrian war in the Dniester River valleywere of great help. I am also thankful to Tahir Alizada, whose intelligence and support always inspired me in this academic journey, and to Matei Sasu for reading my manuscript and providing valuable suggestions.

I also extend sincere thanks to my colleagues in the USA. Dovilė Budrytė and Donald J. Raleigh always encouraged me as I was making progress on this work. Albert Ringelstein’s detailed feedback and meticulous language suggestions have been instrumental in improving the quality of my final manuscript draft.

In the course of this long journey, I have also benefited from the assistance of colleagues, scholars, friends, and public officials in Moldova, Romania, Ukraine, the EU, and Russia. Special thanks go to Eugen Cernenchi, Dorin Cimpoeșu, Ion Costaș, Victor Damian, Andriy Deshchytsia, Nina Gorbaceva, Sergiy L. Gnatiuk, Svitlana Iakubovska, Sergey P. Karpov, Iosif Moldovanu, Octavian Munteanu, Sergiu Musteață, Dirk Schübel, Ion Stavilă, Domnița Tomescu, Victor Țvircun, and Valentin Yakushik.

I am eternally grateful to my high school teacher from my native town Drochia, the late Petru A. Trifăilă, thanks to whom I decided to become a historian. I should mention Professor Demir M. Dragnev, who supervised my first doctoral project in the 1990s in Moldova and helped me become a researcher. I am equally thankful to everyone who offered me research opportunities during my fieldwork in Eastern Europe, as much as to the officials from the German and Romanian embassies in Chisinau, the Delegation of the EU, and the OSCE Mission to Moldova who kindly agreed to interview with me.

The materials identified and compiled from libraries and archives represent a significant part of this study, and I would like to acknowledge the professionalism of librarians and archivists who I worked with in Edmonton, Chisinau, Bucharest, Tiraspol, and Tighina-Bendery.1* I also want to thank scholars, public figures, political analysts, and everyone else who was directly or indirectly related to the appearance of this book.

To complete this interdisciplinary project, I benefited significantly from scholarships and awards. The Frank Peers Graduate Research Award, the Queen Elizabeth II Graduate Scholarship, the Kule Institute of Advanced Studies Dissertation Fellowship, the Andrew Stewart Memorial Graduate Prize, the David R. Marples Eastern European Travel Award, and the Faculty of Arts International Travel Award at the University of Alberta allowed me to conduct research abroad and gather various types of data.

The publication of my book was also made possible, in part, by the Extended Funding Grant and the Professional Development Fund from Red Deer Polytechnic in Red Deer, Alberta, Canada.

My book would not have reached this stage without the anonymous peer-reviewers’ critical and constructive suggestions. They too deserve special thanks. I am thankful to Andreas Umland for including my monograph in the SPPS book series. I thank Elanor Harris for her proofreading and editing services. I also acknowledge the enthusiasm and helpfulness of Katharina Bedorf, Jana Dävers, Valerie Lange, Malisa Mahler, Michaela Nickel, and others at ibidem-Verlag / ibidem Press, as well.

In writing this book and in all my academic undertakings, my wife Marina’s infinite patience, understanding, and optimism, and the support of my daughters, Mihaela and Jessica Diana Ksenia, have been—needless to say—immeasurable. Heartfelt words of appreciation are due to my sister Elena Cotos. Not only has she stood by me all these years, providing unwavering help and expertise, and insightful advice, her impressive scholarly achievements have served as excellent motivational examples for my research and career endeavors.

I dedicate this book to my family and to my parents—my father Vladimir and my late mother Vera, who always believed in me and gave me strength, courage, and energy.

1* Tighina (Bendery) is a Moldovan town located on the right-bank ofthe Dniester River. As it was influenced by the idea of separating from the Republic of Moldova, it became an outpost of the breakaway Transnistrian republic. The Moldovans call it “Tighina,” that is, the name in Romanian language they gave to this locality before the Ottomans changed it to “Bender” in the sixteenth century. To the Transnistrians it remained as “Bendery,” the name kept both by the tsarist and Soviet authorities. In this book, for the sake of clarity, I use both names of the place, i.e., Tighina-Bendery.

Abbreviations

AEI

Alianța pentru Integrare Europeană

Alliance for European Integration

ANRM

Arhiva Naţională a Republicii Moldova.

ANR

Arhivele Naționale ale României

AOSPRM

Arhiva Organizaţiilor Social-Politice din Republica Moldova

AUPSICC

Arhiva Universității Pedagogice de Stat Ion Creangă din Chisinău

APE

Asociaţia pentru Politică Externă

Foreign Policy Association

ASM

Academy of Sciences of Moldova

CIS

Commonwealth of Independent States

CSAPOK

Central State Archive of Public Organizations in Kyiv

CPSU

Communist Party of the Soviet Union

CSCE

Commission on Security and Cooperation in Europe

CSOs

Civil Society Organizations

DMSR

Mişcarea Democratică în Sprijinul Restructurării/Democratic Movementfor Support of Perestroika

ECHR

European Court of Human Rights

ENP

European Neighborhood Policy

EU

European Union

EUBAM

European Union Border Assistance Mission

GKChP

Gosudarstvennyi Komitet po Chrezvychainomu Polozheniyu/State Committee on the State of Emergency

GUAM

Georgia, Ukraine, Azerbaijan, Moldova

GULAG

Glavnoe Upravlenie Lagerei

Chief Administration of the Camps

ICSPU

Ion Creangă State Pedagogical University

JCC

Joint Control Commission

KGB

Komitet Gosudarstvennoi Bezopasnosti

Committee for State Security

MASSR

Moldavian Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic

MDR

Moldavian Democratic Republic

MFA

Ministry of Foreign Affairs

MIA

Ministry of Internal Affairs

MSSR

Moldavian Soviet Socialist Republic

NATO

North Atlantic Treaty Organization

NGOs

Non-Governmental Organizations

OMON

Otdel Militsii Osobogo Naznacheniya

Special Purpose Police Unit

OGRF

OGRV

Operativnaia Gruppa Rossiiskikh Voisk v Pridnestrovie/Operational Group of Russian Forces in Transnistria

OSCE

Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe

OSTK

Ob’edinonnyi Sovet Trudovykh Kollektivov United Work Collective Council

OUN

Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists

PFM

Popular Front of Moldavia (Moldova)

RSFSR

Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic

TMR/PMR

Transnistrian Moldovan Republic/Pridnestrovian Moldavian Republic

TMSSR

Transnistrian Moldovan Soviet Socialist Republic

UNA-UNSO

Ukrainian National Assembly-Ukrainian People’s Self-Defense

UN

United Nations

UPA

Ukrainian Insurgent Army

UPR/UNR

Ukrainian People’s Republic

Ukrainian National Republic

USSR

Union of Soviet Socialist Republics

IntroductionTheoretical Framework: Nation-Building and Separatism

The breakup of the Soviet Union and the fall of communism shattered the contemporary world and notably changed the international borders in Central and Eastern Europe (Map 1). The struggle against totalitarianism, centrifugal irredentism oriented toward political independence, and cultural revival dramatically impacted the fate of the twentieth-century states. Pre-World War II nation-states were re-established (e.g., the Baltic States), and new ones emerged (e.g., North Macedonia, Ukraine, Belarus, Georgia, and Moldova). Elites and ordinary people in the former socialist camp experienced the joy of freedom and sovereignty differently.

The dissolution of Czechoslovakia took place without bloodshed, or as Eric Stein put it, it was a rather “peaceful divorce […] [and] a startling exception” compared to other places.1 For example, separatist movements by strong ethnic minorities emerged on the territories of the former USSR and Yugoslavia. Georgia resisted secessionism in Southern Ossetia and Abkhazia. Armenia and Azerbaijan continued their dispute over the Nagorno-Karabakh region. Ukraine faced aspirations for independence in Crimea and separatism in Donbas, Albanians in Kosovo challenged Serbia, while Serbian nationalism obstructed nation-building in Bosnia and Croatia.

This book focuses on nation-building and Transnistrian separatism in Moldova,—a former imperial Russia borderland, Soviet republic, and post-Soviet state where the interests of Moscow and the West collide (Map 2). Similar to Ukraine, the Republic of Moldova is a transitional zone between Europe and Eurasia, a country that faces the challenges of a post-communist society, and represents a microcosm of mixed ethnic, cultural, and political identities. Domestic secessionism, the so-called ‘frozen conflict’ over Transnistria, citizens’ unsettled civic and ethnic identities, political instability, and failed economic reforms challenged this fragile post-Soviet state.

The book has three main objectives.First, it describes the historical background and geopolitical roots of the modern nation- and state-building in the Republic of Moldova. Second, the book investigates problems of separatism and the implication of the major international actors in the settlement of the Transnistrian conflict. It indicates that not only “patterns [of Russian] power and dominance remained unsettlingly in evidence” in Eastern Europe,2 but also that domestic contradictions and West-East rivalry generated pro-Russian irredentism and obstructed national reconciliation in this country. Finally, the study shows how a politically and territorially divided nation forges exclusivist ethnic and political identities through education, political symbolism, and nationality policies. The aim is to demonstrate that separatism generates mutually exclusive nation-building projects on the territory of a single state, where existing historical preconditions and geopolitical realities interweave and impede the construction of a modern nation-state. Geopolitical preconditions and historical past, which constitute the foundation of the domestic yet internationalized conflict in the Republic of Moldova, transformed this post-Soviet republic into de facto two independent entities: Moldova and Transnistria.3

The Historical Context

Two centuries of imperial might transformed Russia into a multiethnic state in which various non-Russian and non-Eastern Orthodox Church nations conflicted with the central authority. Expansion, conquest, and annexation wars made many contemporary nations subjects of the Romanov realm. In Europe, Poland-Lithuania ceased to exist due to its more powerful neighbors, i.e., Austria, Prussia, and Russia (1772, 1793, and 1795). Earlier, during the Khmelnytsky Uprising against the Poles some regions of modern-day Ukraine became part of Muscovy (1654), while in the Caucasus, Georgia was incorporated into the Russian Empire at the beginning of the nineteenth century.

Most of the lands that today belong to the Republic of Moldova shared a similar dramatic past. The medieval Principality of Moldavia, the independence of which Hungary and Poland challenged at first (Map 3), ended up as a vassal state to the Sublime Porte in 1538 (Map 4). A few decades later, Wallachia’s ruler Mihai the Brave attempted to unite Moldavia, Walachia, and Transylvania under his scepter in 1600. However, as the Habsburgs assassinated the protagonist of this project, the unification of the lands populated by Romanian speakers was postponed to the mid-19th century, an epoch that Stefan Berger called “the classical century of nationalism and of the aspiring nation-state.”4 During the early modern times, the Principality of Moldavia remained a disputed land between Poles, Austrians, and Turks until the emerging Russian Empire came onto the scene under Peter the Great (1682–1725). Russia’s interests in the Balkans and wish to conquer Constantinople transformed this Danubian principality into a bloody battlefield between Ottomans and Russians. Moldavia along with Wallachia became an arena of diplomatic intrigues in which the monarchic courts in Vienna, Istanbul, and St. Petersburg appeared as irreconcilable political orchestrators.

Scholars often make references to the partitions of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth when they speak about state-building, identity construction, and imperial expansion in the nineteenth century.5 Their interest can be explained by the role this country played in European history and the complex nation-building processes that took place in its territory. However, Poland-Lithuania was not the only one divided by the Great Powers. Other countries had a similar fate (e.g., Hungary, Wallachia), and Moldavia was among them as well. The first time, the Ottomans ceded to the Habsburgs the northwestern region known as Bukovina (1775); the second time was when the Turks lost to the Russians the eastern half of that principality after the conclusion of the Russo–Turkish war in 1812. The Romanovs named the newly acquired province “Bessarabia.”6 Whereas the western part of Moldavia and Wallachia united in 1859, created Romania in 1866 (Map 5), and fought against the Turks for independence during 1877–1878, the eastern part of Moldavia (Bessarabia) became Russia’s new borderland and a strategic gate into the Balkan Peninsula.

In its quest for imperial power, Russia included lands that once belonged to different states, which were populated by non-Russian and often non-Orthodox believers. Without exception, all territorial acquisitions were to be integrated politically, economically, and culturally through Russification into the larger imperial framework.7 Some provinces benefited from the various levels of self-government; others were deprived of any “national” (ethnic) autonomy. However, although “Russians were strict in their refusal of Polish self-governance,”8 the legal status of the Kingdom of Poland and that of the Grand Duchy of Finland within the empire cannot be compared with the fate of the lands that today belong to Belarus, Ukraine or even Lithuania.9While in the case of the former the functionality of the “national” establishments was evident, i.e., the Diet in Finland and the Sejm in Poland, no such institutions ever existed in the case of the latter.

The situation of eastern Moldavia, or the territory, which Russians renamed into Bessarabia, was somewhat different. At first glance, it seemed to be similar to that of Russia’s Poland and Finland. Six years after the annexation (1818) the region was granted autonomy; the ancient privileges of the local nobility were confirmed, and traditional administrative units were preserved.10 Nonetheless, the essential difference between Bessarabia’s status and that of Poland and Finland consisted of the type of autonomy it was granted. The nature of its self-governance was not “national” (ethnic) as in the case of the Poles and Finns; rather, a purely Russian administrative model was introduced in the region.

Although initially in the region Russia allowed the use of the Moldavian Principality laws and language, Russia’s policymakers had no intention to provide national autonomy to the Moldavian aristocracy in the province. In their view, Bessarabia’s “particular way of governance” (osobyi obraz upravleniia) meant exclusively the imperial legislative, judicial, and executive bodies rather than a provincial diet based on historical traditions and composed of the local nobles.11 Ten years later, in 1828, the region lost its quasi-administrative autonomy and became an ordinary province until the Romanovs lost the throne in 1917.12 As subjects of the Tsar, the Romanian-speaking Moldavians suffered culturally from Russification and economically from the colonization of their land with the intra-state migrants (e.g., Ukrainians and Russians), and foreigners (e.g., Bulgarians, Gagauzes,13 Germans, and others).14

As mentioned above, similar to other annexed lands, no signs of national self-governance existed in Bessarabia under Russian rule. The only appointed ethnic Moldavian governor was Scarlat Sturdza (1812–1813), a boyar who settled in Russia after the conclusion of the Russo-Turkish War in 1792.15 However, he was soon replaced by the representatives of the imperial administration for Russians, as George F. Jewsbury pointed out, “had no illusions about the Romanians’ dedication to work for the good of the [...] empire.”16

The forced integration within the Russian Empire made impossible the survival of any kind of state institutions that would have reminded the natives of Eastern Moldavia (Bessarabia) about the Principality of Moldavia from which they had been separated in 1812. The contacts between the people that for almost five centuries belonged to the same state and shared cultural identities with Romanian-speaking western Moldavians, Wallachians, and Transylvanians were impeded. The situation changed only after Nicholas II abdicated and Moldavian nationalism surfaced on the waves of the Russian revolutions in 1917. The Moldavian Democratic Republic (MDR) was formed in December 1917 and the union with Romania in 1918 reintegrated Romanian-speaking Moldavians of Bessarabia into the framework of the modern Romanian nationhood established during 1859–1862.

The eastern part of the Moldavian Principality, i.e., the former Russian gubernia of Bessarabia (excepting the areas that the Kremlin transferred later to the Ukrainian SSR in 1940 (Map 6), i.e., Northern and Southern Bessarabia), represents the core land of contemporary Republic of Moldova. However, its predecessor, the Moldavian SSR (MSSR), which Moscow created after the USSR invaded Romania in June 1940, was composed of two separate units. The MSSR (Map 7) was created from the territory of most of Bessarabia to which several districts of the Moldavian Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic (MASSR) established in Ukraine in 1924, were added. The land from which the MASSR emerged and where Moldavians lived alongside other ethnicities belonged in the pre-modern era to Poland-Lithuania and the Crimean Khanate. It was also disputed between the Ottomans and Poles and briefly controlled by the Zaporozhian Cossacks (Map 4). The Ottoman Porte lost this territory once Russia expanded westward and for two decades that followed (1792–1812), the Dniester River was the new Russo-Turkish frontier in Eastern Europe.

In the 19th century, Russian imperial authorities divided the lands, which they incorporated in 1792 between the Podolia and Kherson gubernias. After the 1917 events they briefly belonged to the pre-Soviet Ukrainian state (1918–1920), were given to the MASSR in 1924, and parts of them were transferred to the MSSR in 1940. Since 1990, this territory has been controlled by the self-proclaimed Transnistrian Moldovan Republic (TMR). The Transnistrian republic is a product of the effort Moscow made to halt re-Romanianization and de-Sovietization in Soviet Moldavia. Its establishment and existence, but in particular its survival, represent a geopolitical attempt of the Kremlin to preserve Russia’s influence in Moldova based on the pro-Russian orientated elite, population, and Transnistrian quasi-state.

Nationalism and Separatism: Linking the Imperial and Soviet Past with the Present

The nationalistic movement and centrifugal separatism challenged the promoters of the imperial idea and confronted the guardians of the nineteenth-century empires. The Poles rose against the Romanovs, the Hungarians managed to impose themselves against the German Austrians, and the Greeks fought for their freedom against the Ottomans. The once-powerful empires of the Habsburgs and Ottomans disappeared and remained a historical legacy of the past. Moreover, they had no potency to re-emerge and there were no emancipated nations that wished for their ‘reincarnation.’ The case of Russia seems to be different. There, the communist ideology and the spirit of the revolution were put in place and preconditioned the projection of a greater (Soviet-born) Russia on the ruins of the empire that fell in 1917.

The Bolsheviks employed the idea of people’s right to self-determination for their own interests. Yet, in the given circumstances of post-Great War Europe and of civil war in Russia they had no choice but to lose significant parts of the disintegrated empire to save the emerging Soviet state. National revival, political ambitions, and the determination to gain independence allowed Poland, Finland, and the Baltic States to appear on the political map of the modern world after 1918. The overthrow of the Provisional Government in Petrograd in October 1917 put several immediate tasks on the agenda of Vladimir Lenin and his close associates. The war with the German Empire had to be ended, the domestic political opposition annihilated or at least subdued, and the strategy of preserving Romanovs’ territorial possessions, when and where it was possible, had to be implemented as well.

At first, several ephemeral Soviet republics already appeared under the red flags of the Bolsheviks in 1918. In Ukraine, the Odesa Soviet Republic, the Soviet Socialist Republic of the Tauride, the Ukrainian SSR, and the Donetsk-Kryvyi Rih Soviet Republic, were all counterposed to the independentist Ukrainian People’s Republic with Kyiv as its capital city (Map 5).17 On the other hand, the Soviet republics of Lithuania and Belarus were merged in 1919 into the Lit-Bel—an artificially united polity of two nations designed to keep them as integral parts of Soviet Russia.18 Last but not least in this chain of the short-lived quasi-states was the Bessarabian SSR, which the pro-Russian Bolsheviks proclaimed in Odesa in the same year.19That was nothing but a direct political response that Moscow gave to Bucharest. The latter incorporated Bessarabia along with the Habsburgs’ Transylvania and Bukovina in 1918 as it considered all these provinces indissoluble parts of the historical Romanian nationhood. The Soviet government did not give up or stand back from the aim to recover territories of Tsarist Russia after its initial failure to do so. The end of the civil war in 1921 and the legalization of the first proletarian state in 1922 were events that allowed Moscow,—the capital city of Bolshevik Russia,—to reconsider its tactics and strategies for achieving such a goal. Thus, it made use of what Terry Martin has called the Piedmont Principle and created a number of ethnocentric polities at the border with the enemy states.20In fact, they targeted those nations that successfully broke away from imperial Russia on the waves of revolution and Great War and against whom Soviet Russia had territorial claims. The Soviet republics of Belorussia and Ukraine were meant to challenge Poland, while the autonomous republics of Moldavia in Soviet Ukraine and Karelia in the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic (RSFSR) were “political propagandistic” factors to be played against Romania and Finland.21 Although there was no strong pro-Russian secessionist movement beyond the Soviet border if at all, the combination of an alleged historical Slavic brotherhood with communist propaganda was widely exploited with respect to Ukrainians and Belarusians in the interwar Piłsudski’s Poland.

Romanian-speaking Moldavians of Bessarabia and the Finns were in a similar situation. In their case, ethnicity and ideology also served as a camouflaged excuse for extending Soviet borderlines under the slogans of liberation and internationalism. In the interwar period, Moscow relied first of all on the re-invented Piedmonts and on pro-Soviet oriented agents of Bolshevism sympathetic to socialism, rather than on the will of the masses of the local titular nations. Nonetheless, the USSR did not hesitate to use force against Poland and Finland in 1939 and intimidation and blackmail against Romania in 1940 to get what it could not achieve by diplomatic means or through the functionality of the Soviet “Piedmonts” that in fact failed geopolitically.

One may argue that the nationality policies that the Communist Party implemented throughout the entire period of the existence of the USSR, but specifically after the conclusion of the Great Patriotic War (1941–1945), created “[necessary] conditions conducive to Russian irredentism” in post-Soviet republics shortly before and after 1991.22 The all-union republics had not only been made economically dependent on each other but they were also fused with what has become known as homo sovieticus. It was the latter who perceived Motherland Russia as the Soviet Union, to whom Russian became the only lingua franca and to whom any corner of the immense country represented a welcoming piece of the great native land.

In addition, the state-administrated in-migration of Russians and Russified minorities in non-Russian republics, the transfer of the territories from one republic to another, and the significantly changed intra-state borders gave the Kremlin sufficient tools to interfere in the nation-building process in the newly emerged sovereign states after 1991.23 This time, in contrast to the interwar period and instead of the communist idea, another sort of ideology was and is being used—the political support and military defense of Russians and pro-Russia minorities in the former Soviet republics. Since the USSR began to collapse and during the decades that followed, Moscow relied on the “Russian immigrant population […] perceived as instruments of former Soviet oppression and as a possible fifth column in case of Russian revanchism,” particularly in those territories, which the Kremlin considers as strategic pieces of Russia’s ‘Near Abroad.’24

The annexation of Crimea in 2014 and the war that is underway currently in Ukraine demonstrate patterns of historical pro-Russian separatism in the provinces that belonged earlier to the Romanov dynasty and modern-day Russia’s keen interest in the countries that emerged in the territories of the collapsed USSR. Moldova is an interesting precedent of a political experiment, where pro-Romanian ethnic nationalism and pro-Russian irredentism have been in direct conflict for almost four decades now. There, separatism in Transnistria, which is a small but compact-living, institutionally well-organized, and politically-mobilized splinter of the so-called ‘Russian World’ [Russkiy Mir], obstructs state-building, impedes national reconciliation, and makes the reintegration of this divided country improbable for some time.

Objectives, Research Questions, and Working Assumptions

This study analyzes the process of nation and state-building in modern-day Moldova. It bridges the national revival of the Romanian-speaking Moldovans with the rise of anti-Moldovan resistance and pro-Russian separatism in Transnistria. It argues that the unsettled identities in the past, the shattered post-Soviet nationhood, and the impact of international factors on domestic affairs have impeded state and identity construction in this country since the breakup of the USSR. It reveals how the conflict over the legal status of the TMR obstructed national reconciliation, territorial reintegration, and political reunification of Moldovan nationhood.

This interdisciplinary project involves history as well as international relations, political science, and studies in ethnicity, culture, nationalism, and conflictology. It addresses such issues as the influence of historical preconditions on the nation-building process in the Republic of Moldova, the reasons for its failure in the past, and the impact of pro-Romanian nationalism and the Russian-speaking minority’s centrifugal tendencies on the current geopolitical situation in this country. The study relies on the premise that the construction of a small-sized nation, based on ethnocentric or civic principles, is determined by the ability of the local elites to negotiate and resolve domestic political disputes, where the involvement of international actors is more than crucial. The questions guiding the study were as follows:

To what extent did Moldovan, Romanian, and Soviet state-building and identity construction echo the national revival of Romanian speakers and the irredentist mobilization of Russian speakers in the late 1980s–early 1990s?

What were the circumstances that led to the outbreak of the war in the eastern districts of the Republic of Moldova in 1992, and how did its geopolitical consequences impact the internationalized conflict resolution process?

Why were the negotiations stalled, and why did the attempts to reconcile Chisinau and Tiraspol fail?

What strategy did the international mediators employ in their attempts to resolve the Transnistrian problem?

How was the conflict between Moldovans and Transnistrians reflected in the domestic political discourse?

Why and how can separatism generate mutually exclusive nation-building projects on the territory of a single state?

This book describes the separatist movement in the Republic of Moldova as a domestic, yet internationalized impediment to the Euro-Atlantic integration of the country. There are three central working assumptions. First, the collapse of the USSR did not prevent post-Soviet Russia from interfering with the domestic affairs of the former sister republics. On the contrary, protracted conflicts like that in Moldova, Georgia, and more recently in Ukraine, have contributed to the Russian Federation’s reaffirmation as a regional power and exposed its global geopolitical ambitions.

The second working assumption is that the term “frozen conflict” is inappropriate for the Transnistrian problem. This term, widely used in publications and often utilized by scholars, politicians, and the media, is in fact a source of confusion. It neither reflects the real state of affairs in the Republic of Moldova nor does it correspond to the situation beyond Moldova’s borders.

The third assumption is the presupposition that the irreconcilable legacy of the Romanian, imperial Russian, and Soviet past, the conflicting vectors of foreign and domestic leadership policies, and the geopolitical orientation of ordinary citizens have transformed the Republic of Moldova into the hostage of a continuing political crisis. This impedes nation-building, prevents reconciliation, and places it before a challenging choice—either to become part of the Western world or to remain an object of Russia’s ‘Near Abroad’ and ‘Russian World.’

Prior Research: Historiography and Geopolitics

After the iron curtain divided the world into two ideologically rival camps, Soviet history became one of the most popular subjects for scholars and politicians.25 The scholarship was concentrated on anti-Soviet resistance, nationalities policies of the Communist Party, and many other topics that revealed, from the Western perspective, the complex nature of the relations between the Russian center and non-Russian periphery.26 The disappearance of the USSR, an event which Tony Judt called “a remarkable affair, unparalleled in modern history,”27 facilitated research in the studies of nationalities in the former Soviet Union and about the newly established independent states.28 The historiography was enriched by a series of works published by Ronald Grigor Suny, Terry Martin, and Francine Hirsch, to name the authors of the most fundamental opuses dedicated to nationalism and nationality policies in the USSR.29

The processes that perestroika and glasnost generated and the events that followed afterward opened new research directions in Western scholarship. The turbulent times, which encompassed state- and nation-building and the quest for national identity in the post-Soviet era, have increased the interest in the developments of the former Soviet republics.30 In addition, the enlargement of the EU and the expansion of NATO into the countries that earlier belonged to the communist camp or were subjects of the USSR stimulated the publication of works that explored the re-emerging confrontation between the West and Russia for geopolitical spheres of influence.31 Noteworthy, the internal and intra-state (often called “frozen”) conflicts and Russia’s struggle to resurrect itself as a Great Power encouraged scholars to pay more attention to the countries in which Moscow demonstrates a close interest.32 Namely, in this context, the Republic of Moldova appears among other case studies under scholarly investigation in which its fate was partially covered or touched.33

Over the last thirty years, scholars have published numerous books and articles related to the struggle of the Republic of Moldova to build a modern state and an authentic civil society. However, to date, there is no in-depth study examining the complex international and regional influences exerted on the origins, evolution, and later developments of the Transnistrian conflict. The same can be said about the impact of the pro-Russian separatism on nation-building in Moldova, Moldova’s course toward Euro-Atlantic integration, and its attempts to resist the Kremlin’s interference in domestic affairs and foreign policy.

Various approaches have surfaced in the recent Western scholarship with respect to Moldova. Charles King briefly discussed the “Transnistrian conundrum” in his study on Moldovans, as did Matthew H. Ciscel in a monograph dedicated to the language identity of the country’s titular nation.34 Stefan Troebst has focused on state-building in Moldova’s self-proclaimed Transnistrian entity; Stefan Wolff has discussed the perspectives of conflict resolution, while Claire Gordon has written about the EU involvement in the negotiation process.35

Concerning the role Russia has played in Moldova’s national project and diplomatic defense against the pro-Moscow secessionists, the books by Bertil Nygren and William H. Hill are worth mentioning.36 While the former integrated the Transnistrian problem into a broader analysis of Russia’s foreign policy toward the former Soviet republics, the latter attempted to learn lessons from the West’s relations with Russia based exclusively on the example of the Moldovan-Transnistrian confrontation. Furthermore, with the ongoing military conflict that broke out in the Donbas region in Ukraine in 2014, there is a tendency in scholarship to contextualize, compare and contrast it with the events that took place in Moldova in 1992.37 In some cases, when mentioned in publications about Ukraine, post-Soviet Moldova is referred to as a “cleft country.”38 In other cases, Transnistria falls under the category of “gangster states.”39

A more recent book by Rebecca Haynes offers an interesting account of the history of Moldova, starting with its antiquity (“Origins”) to the present day (“Democratic Politics”). The author discusses all the stages of the modern Moldovan nation-state and the circumstances surrounding its development.40 In addition, Johannes Socher, while focusing on Russia and self-determination movements in the post-Soviet republics, dedicated an interesting sub-chapter to Moldova’s Transnistria.41