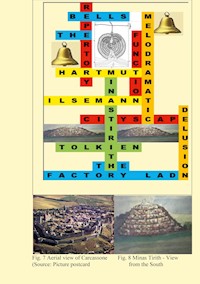

Analyses of 19th Century Melodrama plays and The Symbolic Function of Cityscape in J.R.R. Tolkiens The Lord of the Rings E-Book

Hartmut Ilsemann

Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Books on Demand

- Kategorie: Fachliteratur

- Sprache: Englisch

Der Band umfasst drei Aufsätze, zwei davon behandeln Rezeption und Strukturierung von Melodramen im neunzehnten Jahrhundert. Analysiert werden The Factory Lad (Walker) und The Bells (Lewis). Der dritte Aufsatz stellt die Symbolfunktion der Stadtlandschaft in Tolkiens The Lord of the Rings dar. Die Darstellung erfolgte vollständig in englischer Sprache.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 111

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Preface

This volume contains the English-language print version of my essays published in German in the 1980s and 1990s.

These are:

Repertoireabhängige Steuerung der Zuschauerwahrnehmung und Konkretisation von Wahn in Leopold Lewis' The Bells, in Wahn in Literarischen Texten, L. Glage u. J. Rublack, Frankfurt: R.G. Fischer, 1983, 80-93.

Repertoire-dependent control of audience perception and concretisation of delusion in Leopold Lewis's The Bells, Norderstedt: BoD, 2022.

Radikalismus im Melodrama des 19. Jahrhundert, in Radikalismus in Literatur und Gesellschaft des 19. Jahrhunderts, hrsg. G. Claeys u. L. Glage, Frankfurt: Peter Lang, 1987, 65-83.

Radicalism in the Melodrama of the Early Nineteenth Century, in Melodrama: The Cultural Emergence of a Genre. Ed. M. Hays and A. Nikolopoulos, New York: St. Martin's Press, 1996, 191-206. Reprint Norderstedt: BoD, 2022,

Die Symbolfunktion der Stadtlandschaft in J.R.R.Tolkiens The Lord of the Rings in The Green Knight, Festschrift für G. Birkner, 12. Juli 2006.

The symbolic function of the cityscape in J.R.R. Tolkien's The Lord of the Rings, Norderstedt: BoD, 2022,

As to the melodramatic interpretation of The Bells I am particularly grateful to Joanne Wood and Andrew French, two former students of Bristol University, who arranged a first translation into English. I have also greatly benefited from the stimulus, correction, or information imparted by my colleagues in the English Department of Hanover University regarding the treatment of radicalism in nineteenth-century melodrama. Last but not least the approach in the treatment of the theme of the urban landscape is influenced by Gerd Birkner's reception aesthetics and was supplemented with structuralist procedures.

Contents

Preface

THE VICTORIAN PERCEPTION OF MADNESS IN LEOPOLD LEWIS`S THE BELLS

Elements of literary repertoire

Extra-textual Repertory Elements

Psychoanalytical Decoding

Conclusions

Literature

RADICALISM IN THE MELODRAMA OF THE EARLY NINETEENTH CENTURY

Literature

THE SYMBOLIC FUNCTION OF THE CITYSCAPE IN J.R.R. TOLKIEN'S THE LORD OF THE RINGS

Literature

The Victorian perception of madness in Leopold Lewis`s The Bells

When the melodramatic play The Bells by Leopold Lewis first appeared on the stage of the Royal Lyceum Theatre in London in 1871 it met an audience which was deeply impressed by the subtlety that Henry Irving lent to the leading character`s consciousness. For more than thirty years Irving excelled in this role by plunging into the sufferings of a tormented mind, and he played the role of the mayor Mathias so brilliantly that The Bells became one of Queen Victoria`s favourite plays.1

It seems to be obvious that there was a deep affinity between the play and the late-Victorian audience. This short study attempts to explain the attraction between the audience and the presentation of insanity by portraying the aesthetic experience that was typical of Victorian playgoers and was also ingrained in the textual structure. Often referred to as repertoire,2 these effect-producing elements of drama will be identified firstly as melodramatic mode of reception whose main task it is to create expectations and to build up hypotheses, particularly at the opening of the play, secondly as sentimental control which derives from 18th century domestic drama and arouses the audience`s compassion for the hero`s misfortune, and thirdly as a revival of neo-Platonic thought, whereby the main character`s insanity and subsequent death are revealed as a transcendentally caused punishment for having committed murder, thus establishing a strong deterrent for the audience against pardoning any such deed. Together with the audience`s knowledge of sensational events in the fields of psychology, hypnosis, and mesmerisation the three elements of the repertoire are intended to explain the play`s outstanding success in late Victorian times. But they also account for the fact that it is regarded as outmoded today. Freudian psychoanalysis, which is part of the modern audience`s repertoire, is capable of elucidating the main character`s steps towards insanity, defying at the same time those norms and values in the character that caused his mental illness and are representative of middle-class Victorian attitudes. Thus the play incorporates the idiosyncracies of Victorian society and the dubious position of man within it. Torn between selfishness and personal gain acknowledged as common practice and as the driving force behind economic processes on the one hand, and the demand for a metaphysically-grounded morality on the other, man seems to have the choice between opting out of the pursuit of wealth and remaining sane, or following the common pattern, which may well result in madness.

Elements of literary repertoire

The first step in determining audience or reader participation and in discovering the control mechanisms which the play`s structure exerts upon the audience lies in registering the situation and the character`s views at the beginning of the play, as these provide an important initial orientation.

The first act opens onto the interior of a village inn in Alsace. A familiar guest enters, knocks the snow from his coat and orders a glass of wine. The dialogue with the landlady reveals when the play is set - it is Christmas Eve, the year 1833, as can later be deduced from the court scene. At the same time, information is provided in this dialogue which - how could it be any different at the beginning of a play - is altogether superfluous within the internal communication system. It therefore has an immediate audience-oriented function in that it directs its attention to the forthcoming wedding of the landlord`s daughter, Annette, to the quartermaster, Christian, stresses the unequal financial situation of the couple, and praises the unselfish attitude of the bride`s father, who is only concerned for his daughter`s happiness. We also learn that he is the much respected mayor of the village.

In between, background music emphasizes the various utterances of the group of guests, which has meanwhile grown, and creates further suspense. In face of the wedding preparations this provides very strong identifications for the spectator and builds up anticipations, within which the young couple together with their parents can be certain of the benevolence of the audience. Pfister sees the clue to the high degree of suspense, next to the identification of the audience with characters, in the giving of information which indicates what the future holds, and as a special form of this the atmospheric and psychic omen.3 This becomes apparent when Christian, the bridegroom, enters to a musical accompaniment, and the conversation of those present turns to the particular weather conditions.

CHRISTIAN. Your winters are very severe here. WALTER. Oh, not every year, Quarter-master! For fifteen years we have not had a winter so severe as this. HANS. No - I do not remember to have seen so much snow since what is called "The Polish Jew`s Winter."4

The following conversation concentrates conspicuously on the events of fifteen years ago. Within the internal communication system the conveying of this information is motivated by the storm which rages outside and by Christian`s ignorance. As to the external communication system, however, it fulfils the function of awakening the audience`s anticipation. Through their repeated treatment, the themes of the murder which took place at that time, and of the expected return of the absent mayor, become points of reference which show a strong affinity with one another. For a while the audience might fear that Mathias could have been attacked on his way home that night, but this thought does not occur to the figures on stage. They recapitulate the events of that night as far as they are known to them. The narration ends at the point when the Jewish tradesman is left alone in Mathias`s bar and is taken up again at the point when the horse and cloak of the murdered man are discovered. Between these two events lies the deed, which no-one is able to say anything about, but at this very moment the storm raging outside shatters the window in the next room. When Christian is finally called outside by one of his gendarmes the non-explanation of the case remains behind in the room as a fact. Meanwhile, the other guests continue to discuss the forthcoming wedding in positive terms and to stress the high regard generally felt for the bride`s father Mathias. Any fears that something could have happened to Mathias are dispersed when he enters the bar to the accompaniment of a powerful chord. In this way one possible connection between the murder and Mathias has proved to be invalid through the structure of events, but among the references to Mathias his connection with the murder has been stressed.

What Mathias tells of his journey carries even more weight and significance in setting up a hypothesis. A mesmerist from Paris had hypnotized citizens in the market place and had asked them questions to which they would never have given an answer had they been aware. Such an ability appears sinister to Mathias. He quickly changes the subject, gives Annette the wedding present that he has brought with him, and it seems as though the wedding sequence, which had been in the foreground until now, will continue to be so, when one of the guests, completely unmotivated, and using practically the same words, takes up once again the topic of the weather and the death of the Polish Jew.

Mathias, who had just made himself comfortable, instantaneously stops drinking and the sound of sledge-bells can be heard in the distance. To make sure that he is not hearing things, Mathias asks the others whether they can also hear bells ringing, to which their answer is no. He shivers, the lighting changes and through the back wall of the room which has become transparent he sees a sledge and in it the figure of the Polish Jew. No-one else shares this vision. The mayor`s sudden collapse is regarded by them as a result of hypothermia which must have been caused by his arduous journey through the snow-storm.

So at the end of the first act Mathias`s hallucinatory perception is clear to the audience. What is more, it correlates with their own perception and contrasts with that of the play`s figures who attempt to rationalise Mathias`s behaviour because they lack the ability to understand anything which lies beyond their fictional level. Furthermore, with the focus now on Mathias there is a shift within the framework of suspense in that those events concerning the murder emerge as the main plot, whilst all those connected with the wedding become part of the sub-plot. In place of a putative initial exposition, a successively integrated form of exposition can be found which reveals itself accordingly as actualized past as the murder is confessed, and the increasing tendency towards psychosis is illustrated in soliloquies and inner psychic projections.

First of all, the theatrical conventions familiar to the Victorian audience must be looked into. In contrast to the present day, selective musical entries, even in spoken drama, were common. At this point it would be a good idea to mention the function and literary role of the musical entry. It must be emphasised that it is not motivated by or situated within the internal communication system, but as a convention of the "mélodrame" it signalises character entrances and exits to the audience. In the first act it is a decisive contributory factor in laying stress on particular events, for example the forthcoming marriage between Annette and Christian, and in establishing connections, for instance between the murderous deed and Mathias. The atmospheric effect evokes and strengthens the secrecy around the murder and its consequences, whilst the soft and enticing music of the wedding sequences gives rise to sentimentality.

In the history of drama and dramatic effects both effects belong broadly to melodrama in the early nineteenth century, which, due to its markedness as a play of gothic, supernatural horror, held ready for the spectator a set of criteria by which it could be judged, as well as definite horizons of expectancy. Stereotyped plots and fixated stage characters in sensationhungry melodramas therefore make it possible for us to reconstruct overall expectations.5 So the 19th century audience had to be prepared for the positive casting of the bridal pair and for the connected sequence to be disturbed. The audience also had to fear that the esteemed father figure, Mathias, well endowed with Victorian values, would, by means of a misfortune or some other secret event, be wrongfully robbed of his wealth or even his life. This hypothetical projection is not totally unimportant for the description of suspense. An indication of the starting point for expectations and the consequent participation of the spectator is also relevant in another respect, since it facilitates the description of the dynamics of plot action and of the constantly changing perspectives within the external communication system. This is valid both on the syntagmatic and paradigmatic axis in as far as correspondences to and deviations from the melodramatic receptive mode can be mentioned. What is of interest at the moment, though, is the dynamic process of giving information, which leads to a newly generated comprehension that may be contrasted with the spectator`s initial attitude.