3,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Youcanprint

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

Il testo si presenta come un compendio sulla Siracusa antica della quale l'autore traccia un quadro che spazia dagli albori del V millennio a.C. fino alla conquista araba dell'878. Le argomentazioni, condotte con senso critico e metodo scientifico, riportano alla luce tesi e dibattiti volti a far rivivere le illustri vestigia di una città che seppe essere magnifica.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Ähnliche

Indice

Cover

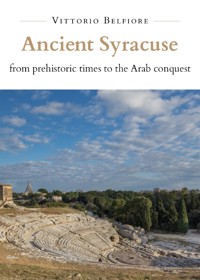

Ancient Syracuse

Vittorio Belfiore

Ancient Syracuse

from prehistoric times to the Arab conquest

Titolo | Ancient Syracuse

Autore | Vittorio Belfiore

ISBN | 979-12-20348-85-0

© 2021 - Tutti i diritti riservati all’Autore

Questa opera è pubblicata direttamente dall'Autore tramite la piattaforma di selfpublishing Youcanprint e l'Autore detiene ogni diritto della stessa in maniera esclusiva. Nessuna parte di questo libro può essere pertanto riprodotta senza il preventivo assenso dell'Autore.

Youcanprint

Via Marco Biagi 6 - 73100 Lecce

www.youcanprint.it

Art draws inspiration from divinity. It is none other than the personification of nature which communicates with mankind through the language of terror and admiration, both astonishing and exalting us, raising and lowering us until we come undone. From this spiritual commotion arose the masterpieces of the pen, chisel and paintbrush, passing ultimately into history as yet unparalleled models of imitation.

Art was once the sacred privilege held by the keepers of an ancient knowledge, initiates who served an exoteric function within the nascent Greek civilization in order to unveil the order of human affairs as connected to a universal nature. The entire system of civilization is a symbol of knowledge born out of the arts through which mankind, inspired by great destinies, ascended to truth.

The Greeks portrayed human events on the stage, representing them through the interaction of hidden and invisible beings. Mankind in such tragedies acted according to the will of fate, functioning as a blind tool for an unseen yet powerful being, a covert presence of implacable operation and whimsical vengeance. The audience of these tragedies was thus transported towards a spiritual and divine path, leading to beauty.

Beauty for the ancient Greeks was associated with goodness: that is, an ideal synthesis of human perfection in which a person’s exterior beauty and moral value are in harmony, an ideal encapsulated in the Greek term kalokagathìa. Beauty was the search for an ideal synthesis of the human body - the perfect proportion between body parts in symmetry and balance as described by Polykleitos in his Canon as the “Greek esthetic spirit”, a beauty underpinned by numbers and precise relationships. In the Greek world, divinity assumed a human form in the body at its most youthful and vigorous, communicating the idea of a perfect beauty, both incorruptible and immortal. Beauty was also found in the order of the kosmos, in which the harmony of things is represented in the three dimensions of the equilateral triangle or tetraktys which characterizes the physical universe.

Thus, the eternal and universal principle of beauty was a Greek ideal, conceived as a continual revelation of the sacred. It symbolized civilization and an expression of a perfect nature, uniting those parts that made up the whole. Beauty was a gift bestowed from the Gods unto man and thus Art, in all its magnificent splendor, communed with the soul and raised it heavenward. Such knowledge arrived in Greece from Jerusalem and Egypt during the time of Solomon via initiatory practices accessible only to a select few, spreading subsequently to Asia Minor before passing into Persia and Syria. From here, following the route of Ulysses, it landed in Sicily where it followed the migrations from East to West, before ultimately arriving at those two columns that the heroic demigod Heracles had established as the limit of the known world.

By virtue of its geographical position, from the fifth millennium BC the city of Syracuse acted as a bridge between the African, European and Asian continents, functioning as a fertile migratory crossroads for the civilizations bordering the Mediterranean Sea. The city is defined by glory and power, its ruins testifying to its past greatness and to its position as a place where history and culture came together and were immortalized in legend. Such is evident in the low-relief apotropaic metope once described between the city’s friezes and triglyphs, depicting a monster with snakes for hair and boar-like fangs: Medusa, the daughter of Phorcys and Ceto, the most beautiful yet only immortal Gorgon, and an archetype of Mediterranean religiosity.

According to legend, one night, Poseidon seduced Medusa in the temple of Athena. The goddess was so angered by this desecration of her temple that she transformed Medusa’s hair into snakes and ensured that whoever stared into her eyes would be turned to stone. While lying asleep in a cavern, Perseus killed the monster by decapitation and escaped being transformed by using his shield to avoid her direct gaze. From Medusa’s mutilated neck sprang two sons, the results of her tryst with Poseidon, named Pegasus and Chrysaor. From the streaming blood, red coral and amphisbaena were born. Perseus then showed the severed head to Atlas, who promptly turned to stone. In exchange for the reflective shield, Perseus brought the severed head to Athena who placed it at the center of her aegis, located in the pediment of the Athenaion of Syracuse.

In March 1917, the renowned archeologist Paolo Orsi, in collaboration with Rosario Carta, resumed work on the archeological excavations around the Athenaion within the external courtyard of the Archbishopric. The area was at that time still unexplored and untouched by construction work. One of the most significant discoveries was three walls, the purpose of which was unknown until one of these was identified as a more archaic Deinomenid temple’s peribolos, (having survived the other two) which once stood in the same spot as the Athenaion. All around, ceramic shards of both Sicel and Hellenic origin were found; ceramic fragments manufactured in bronze and glass paste as well as ornamental and votive objects made of ivory and bone. Among these was the discovery of a large number of ivory and bronze fibulae, which between the seventh and sixth centuries BC would have adorned the peploi of aristocratic Syracusan women as well as piously offered to Athena.

Orsi named these people the Sikeloi or ‘Sicels’, following his patient classification and comparative analysis of a rich yet unknown civilization down to the minutest of details. The Sicels were a primitive people who had however reached a decent level of civilization by the third millennium BC with the development of a certain social order. Within Sicel society, Orsi observed the contemporary existence of high-quality artefacts of foreign origin as well as the local population’s more low-quality attempts to imitate these. These objects were Aegean in origin, having been brought from the most important cities of the Mycenaean world: Cephalonia and Rhodes.

Orsi’s work cast an unexpected light on this most complex of issues regarding pre-Hellenic civilization, allowing us to imagine the Sicels in terms of their habits, defensive requirements, daily needs, and funeral rites. His activities initially focused on the exploration of pre-Hellenic necropolises, discovering tombs in which many examples of indigenous craftsmanship had lain untouched for millennia. His stratigraphic excavations revealed the various phases of ancient Syracuse, shining a light on its slow and laborious ascension from the barbaric customs of the Sicels all the way to the early Archaic period, characterized by an influx of Eastern influences and trade as well as the renewal of the magnificent temples of the Dynomenids. They also illuminated the decline of the subsequent centuries and ultimately the end of Greek civilization, following its only remaining features as they permeated into the Roman years and Byzantine civilization.

Orsi’s interests were not limited solely to the study of paleo-Sicel society, but also covered Hellenic civilization in the center of Ortygia. Following the battle of Himera, the island became the location of an extremely important religious complex. During the fight, the blessing of Athena was said to have manifested itself in a flock of owls, an animal sacred to the goddess, who descended upon the victorious Syracusan army. As a result, the tyrant Gelon, to celebrate his victory and to honor the goddess, demolished the primitive Archaic temple and in its place constructed the Athenaion.

The prior splendor of the original Archaic temple can however be pictured thanks to the discovery of terracotta pieces and architectural features once belonging to the complex. It was built in the seventh century BC in the Doric style, possibly prostyle, and characterized both by the absence of a peristasis and its long and narrow shape. It included a north-facing stairway built with the intention of establishing a ‘zone of veneration’ around the raised area, representing the continuation of an ancient and very sacred cult dedicated to Athena as described in an epigraphic document. Detailed exploration of the area around the Archaic altar also revealed paleo-Greek and Sicel material, as well as a cavity containing a large bronze armilla and proto-Corinthian ceramic fragments.

In the subsoil immediately surrounding the building, geometrically patterned Greek and proto-Corinthian ceramics were unearthed, as well as glass and amber beads, bronze rings, an ivory fibula plate, a small bronze plate, bones belonging to a large animal, and a piece of a basalt ax; an assortment of peculiar yet delightful relics that provide us with a glimpse of primitive religious life in Syracuse. The rites of the first Ortygian colonies took place at the altar, into which a large hole had been excavated in order to drain sacrificial blood into the virgin ground below.

Gelon was a member of the Dynomenid family. A mercenary despot, he sought to ingratiate himself with the Syracusan business class and forge a connection thereby strengthen his tyrannical hold on the city. In order to do this, he demolished the Archaic temple and in 480 BC, using the resultant material, constructed the Athenaion in the highest part of Ortygia. It was built as a peripteral hexastyle and supported by Doric columns which swelled slightly in the middle (an effect known as entasis) and featured twenty vertical grooves, as well as having the echini of the capitals slightly flattened. Of these, there were six standing along the temple’s width and fourteen along its length.

The new temple had a length of 56 meters and a width of 22 meters, standing upon a 3-step stylobate. The cella’s pronaos faced East, whereas the opisthodomos was oriented towards the West. This precise alignment functioned in such a way that the rays from the rising Sun would pass through the temple during the equinoxes, from one end to the other. The cella walls were covered with a series of painted panels, which depicted the Battle of Agathocles against the Carthaginians, as well as seven portraits of the tyrants and kings of Sicily. At the temple door, the shutters featured decorations made of ivory and gold. Pliny also described a panel which depicted compassionate yet dangerous act of the Syracusan Mentor who, during his travels in Syria, removed a thorn from the paw of a wounded lion.

According to tradition, a large copper shield adorned the pediment of the temple. Its elevated position meant that it reflected the Sun’s rays, making it visible even to the most distant sailors and thus bestowing the goddess’s favor on long voyages. It was said that before leaving port, sailors would bring aboard three clay vases filled with honey, incense, and wine. After setting out, they would wait until the glint of the shield was out of sight, at which point the three clay vases would be thrown overboard in order to bring good fortune and invoke the protection of both Athena and Poseidon.

At the edge of the Archaic temple’s foundations, towards the eastern part of the temple, Orsi discovered a series of structures arranged in a row, featuring empty joints. This immediately roused suspicion that this could be a cover for an underlying cavity. This was confirmed by the removal of two smaller boulders from the structure, which revealed an underground tunnel. The first part of the tunnel was particularly interesting, where a fine layer of soil-like sediment had been deposited. Further clues indicated that this structure had undoubtedly been used as a cloaca, disposing of water which drained from the temple above. From the Byzantine era, the tunnel no longer functioned a cloaca but served as a shelter for the Syracusans, who used it to escape from conflict by heading seaward, unexpectedly towards the invading enemy.

Orsi also discovered the remains of a temple in the Ionic style, lying parallel to the Athenaion. The temple was dedicated to Artemis, daughter of Zeus and Leto, who was considered the protector of women in labor and during birth. She was symbolized by the Moon, thought to be the primary matriarch through which female consciousness was exposed to unconscious processes and thus spiritual rebirth. The Moon represented the feminine archetype par excellence, serving as a primitive and original image that was imbued with symbolism and myth in such a way as to impinge on the psyche, despite having no ‘real’ structure.

In her youth, Artemis is said to have asked Zeus for a short peplos, a bow, arrows, and to let her stay a virgin that no man would ever be able to possess. She went hunting accompanied by sixty nymphs, the daughters of Oceanus, as well as twenty other young girls, the daughters of the rivers. Like Artemis, they were all bound the oath of virginity. Ovid tell us in Metamorphoses that Zeus saw the nymph Calisto, whose name in ancient Greek describes her as “the most beautiful”. Seducing her was forbidden due to her position, both as follower and lover of Artemis (according an ancient homosexual initiation rite between adult women and young girls). However, this failed to deter Zeus, who disguised himself as Artemis. While bathing with the other nymphs, Artemis discovered that Calisto was pregnant and thus killed her with an arrow. Zeus, moved by pity and perhaps guilt, supposedly then transformed Calisto into the constellation of Ursa Major, and her unborn baby into Ursa Minor.

Artemis, an orgiastic goddess accompanied by a paredros, was represented in many emblems which included the date palm, the doe, bees, moonlight, and gamebirds. However, the most sacred animal to Artemis was the quail, a bird that would stop in Ortygia in the Springtime during their long migration northwards. It is also said that the river god Alpheus, smitten with Artemis, pursued her throughout Greece before finally arriving in Ortygia where Artemis had taken refuge. There, she and other nymphs supposedly smeared their faces with plaster so as to be indistinguishable from one another, eventually forcing Alpheus to retreat to the sounds of their mocking laughter.

Undoubtedly, the rite of the “she-bears” arrived in Sicily from Greece. The festival known as Brauronia (due to the location of the shrine to Artemis in Brauron) saw Artemis assume the title of ‘Great-She-Bear’ and young girls inducted into her cult as ‘she-bears’. The cult has its origins in a myth that describes how a tame bear, an animal sacred to the goddess, had scratched a young girls’ face near her sanctuary. The girl’s siblings took revenge on the bear and killed it, an act that angered the goddess and led her to unleash a plague on the city of Athens. The Athenians sought help from the Oracle, who instructed them that, in order to placate the goddess, young girls must assume the role of bears in order to replace the animal. In symbolic terms, it signified the devotion of young girls to Artemis prior to marriage: no girl could be married without first having served the goddess as a ‘she-bear’.

Artemis was considered a healer of disease and venerated by shepherds as a protector of herds and flocks: “country song, sing country-song, sweet Muses, in search o’ thee. O a fool in love and a feeble is here, perdye!1”. Since it was customary to perform devotional dances to the goddess accompanied by flutes, she was also named Eleosina and Clitonea, while the virgins who implored her for husbands named her Canephoria. These feasts were written about by Theocritus in several of his idylls, where they describe in detail the rural beauty of the ancient countryside.

The construction of the temple of Artemis, the Artemision, can be dated to approximately the sixth century BC thanks to the discovery of remains located in a sealed well below the foundations. It was built by workers from the island of Samos who had fled their city in the year following the tyrannical reign of Polycrates and found a home with the aristocratic Syracusan landowners, the gamoroi. The temple, constructed using local limestone, was a peripteral temple featuring a wide covered pronaos with several naves and open-air cellae. The structure was supported by six columns along its width and sixteen along its length. These were 15 meters tall and had Samian bases, built by laying the torus over the scotia. These were placed on a rotating device which carved thin notches into the edges of the twenty-eight grooves which decorated the shafts of the columns, a technique imported from Egypt. They also featured volute capitals, whereas the second row of columns in antis were made with only one echinus decorated with kymation, thus without volutes. The two rows of columns around the nucleus of the cella emphasized the monumental character of the temple, which faced eastward in accordance with Greek custom.

Syracuse’s divine protector Artemis is linked to the myth of Arethusa in Cicero’s In Verrem, where he writes: “in hac insula exstrem est fons acquae dulcis, cui nomen Arethusa est, incredibili magnitudine, plenissimus piscium, qui fluctu totus operiretur, nisi munitione ac mole lapidium diiuncts esset a mari”. At the far end of the island, there was a spring named “Arethusa” whose waters were full of fish and whose flow would be completely submerged were it not for an imposing stone wall which separated it from the sea. The sight of this torrent flowing at the island’s craggy base, so crucial for those who dwelled there, amazed Cicero. Its fame extended beyond Ortygia, being reportedly known in Elis and Aetolia by Cretan sailors and thereafter by Greek colonizers all over the Mediterranean. At the time, it was believed that water gave rise to every lifeform, giving rise to the idea of a divine presence at every spring.

Arethusa was the daughter of Nereus and Doris and one of Artemis’s nymphs. Pausanias and Strabo wrote about the myth, in which the young Alpheus is said to have fallen completely in love with her and stopped at nothing seduce her against her will. In order to escape his advances, Arethusa sought refuge in Ortygia and requested the intervention of Artemis, who thus transformed her into a fertile spring. Moved by these events, Zeus transformed Alpheus into a river beginning in Olympia, stretching underneath the Ionian Sea, and arriving at the spring in Ortygia. In this way, the waters of Alpheus and Arethusa would be united forever.

The myth has also inspired a great number of poets, who wrote of a magical world contained in the spring’s crystal waters:

Sicanio praetenta sinu iacet insula contra, Plemyrium undosum, nomen dixere priores Ortygiam. Alpheum fama est huc Elidis amnem occultas egisse vias subter mare: qui nunc ore, Arethusa, tuo Siculis confunditur undis. Iussi numina magna loci veneramur:

“Off the Sicilian shore an island lies, wave-washed Plemyrium, called in olden days Ortygia; here Alpheus, river-god, from Elis flowed by secret sluice, they say, beneath the sea, and mingles at thy mouth, fair Arethusa! with Sicilian waves. Our voices hailed the great gods of the land”

(Virgil, Aeneid, Book III, vv.692-697, trad. Theodore C. Williams)

Albeit in a rather prosaic manner, the myth is said to symbolize the migrations that took place in the eighth century BC, where a great number of people on rather fragile craft landed in Eastern Sicily. Just as the Corinthians colonized the island, Alpheus in river-form flowed towards Ortygia from the source in the wild mountainous Peloponnese.

Privitera also tells us how not even Horatio Nelson was immune to the charms of Ortygia, stopping at the island while travelling to face Napoleon in June 1798. On the 22nd of June, Nelson wrote of the island “thanks to your exertions, we have victualled and watered, and surely, watering at the Fountain of Arethusa, we must have victory”. Nelson went on to defeat the Napoleonic fleet at Nabunikir. Two years later, he was treated to a magnificent welcome back to Syracuse and awarded several honors, including a gold medal from the Senate and a diploma written in Latin, drawn up by Tommaso Gargallo.

Syracuse’s origins can be traced back to people who arrived in eastern Sicily from the northern coasts of Syria and southern Anatolia at the beginning of the fifth century BC. Among the coastal plains dotted with springs and riddled with streams, they found an ideal environment to continue their agricultural and sheep farming practices and thus settled in an area stretching from Syracuse to the Aeolian islands, including the area surrounding Mount Etna. Their establishment in Sicily symbolizes the beginning of an entire civilization, traces of which are identifiable in the settlement of Stentinello, near Syracuse.

Unlike their African predecessors, the people of Stentinello no longer inhabited caverns but instead opted for flatter areas on which they could build a system of cohabitation. These consisted of solid rectangular huts, which were supported by poles driven into the naked bedrock. Such structures, which could resist poor weather conditions, stood together in a village encircled by a trench dug into the rock, which was reinforced by stone aggers. The settlement was oval in shape and covered an area of approximately 220 x 140 meters. Due to the inhabitants’ fears of incursion from the sea (an event that never really transpired in the Aeolian islands due to trade with similar ethnic groups), the village was fortified. This represented one of the first military structures of its kind in Sicily and provided defense for a people to whom both metals and warfare were unknown. They were instead experts in stonecutting and sand, drawing on local materials and creating blades with regular shape, which were occasionally reworked at the end to create scrapers. Plates were made of obsidian imported from nearby Lipari, an exceptionally hard and ductile material.

The Stentinellians also manufactured flint sickles, solidified lava millstones, basalt ax blades, and animal bone awls and smoothers. This polished stone ax symbolizes the period of Neolithization, and played a pivotal role in the deforestation of cultivable areas as well as the gathering of wood for the construction of huts and other tools. The Neolithic was a turning point in the evolution of man, representing humankind’s passage from hunter-gather lifestyle to agricultural practices. Agriculture was the primary source of sustenance for Stentinello, specifically the growing of grain and wheat and the rearing of sheep, goats, cows, and pigs. This period also saw the development of the concept of property, whereby farmers would now come to own both land and livestock.

Furthermore, the Neolithic saw mankind develop a knowledge of natural resources and therein an awareness of materials with the most favorable characteristics for a given task. They also gained awareness of how to control growth rates and production through environmental modification, such as deforestation and irrigation systems. Farmers were forced to construct settlements consisting of stable structures in the vicinity of their land, the high productivity of which permitted some inhabitants to dedicate themselves not only to food production, but also artisanal craftsmanship. As a result, the villages experienced a growing separation between different specialized activities, creating thus distinct categories with in an increasingly complex and articulate set of social strata.

Stentinellian ceramic production was characterized by the unrefined production of large hollow-form vases, such as basins, cups, and tall-footed fruit bowls. These were decorated with linear, geometric or zig-zag incisions pressed into with fingernails, stamps, or valve shells prior to firing. Representations of the human eye were also frequent, represented schematically by rhombi or circles for the eyes, topped by simple or fringed linear elements for the eyebrows. This effect was most intense when using a sequence of diamond shapes around the walls of the vase, which was undoubtedly apotropaic and exorcizing in intent. A finer form of pottery was also produced, characterized by a closed-form variety of artefacts with a smoother and more polished look. Such items swelled in the middle to a width greater than the mouth of the vase and featured a convex base.

Decorative elements commonly consisted of raised white gypsum-like encrustations, often quite exuberant and covering the entire surface of the vase. It is important to note that ceramic decoration assumed a magical, religious, and symbolic function in Neolithic societies. From the moment that a particular shape or decoration became sacred, these would remain virtually unchanged and evolve very slowly over time. This culture’s burial sites, for example, are found all over Sicily (but not in Stentinello proper). They were dug into the rock and generally oval-shaped, in which the deceased would assume in a crouched position.

A finer variety of ceramics was introduced thanks to a second phase of migration originating in the Balkans in the Middle Neolithic, made of a purer and shinier clay. This was often adorned with imprints and painted with two-tone red bands or flames on a lighter background. The decorations, more sober in character, were limited to one or two fine bands around the lip, although this was sometimes avoided altogether. The items found at Stentinello were judged to have originated in this second migration. This was due not only to the presence of rare painted ceramic fragments, but above all thanks to a rich range of decorations, carved and imprinted with an ability and finesse unknown to the first Neolithic colonies.

Scarce traces of other Stentinellian-type settlements have been discovered all along the Syracusan coastline, such as those of Punta Castelluzzo, Terrauzza, Arenella. The areas near Brucoli, Capo Santa Panagia and the Gisira Plateau are also home to such remains. Two coeval villages are thought to have existed on the small island of Ognina, and a settlement in Petraro di Melilli is also considered noteworthy.

The final phase of the Neolithic was characterized by painted ceramics which took their name from the site of Contrada Diana, located at the foot of the acropolis on the island of Lipari and now an archeological park. The style observed at Contrada Diana is indicative of a significant cultural evolution and transformation that stemmed from the influx of new trends and ideas introduced through migration from the Eastern Aegean and the Balkans. This new period marked a decisive change with respect to the Neolithic, manifesting itself in a changing style most evident in ceramic production.

Archeologists have estimated that Contrada Diana covers an area of some 10 hectares. The abundant ceramics discovered there demonstrate a notable improvement in craftsmanship and firing processes, yet the formal repertoire remains much the same as the preceding period. Painted decoration disappears, the ceramics take on a monochrome red-coral color, and the handles are simplified in favor of a more functional and typical ‘spool’ shape. Stratigraphic data allow us to follow the gradual evolution of these ceramics, which can be subdivided into three distinct phases in terms of shape, handles, and surface coloration.

In this first phase, vase shape is very similar to the style of ceramics of the Serra d’Alto style, preserving the high flared lips. The handles assume a more cylindrical or ‘spool’ shape, typical of this period. The decoration consists of red bands, without margins, painted onto a lighter background. The second phase, the height of the lips is greatly reduced, and the spool-shape handles are lengthened and thus become thinner. The vases now feature three colors, but preserving the coral-red color. The final phase at Diana is marked by the disappearance of the lips, and the handles undergo one or two changes. Either they become so small as to become purely symbolic and devoid of any functionality, or they become thicker and heavier, greatly expanding at one end. Painted decoration also becomes considerably more sober, and the vases take on a monochrome coloration consisting of a shinier and more uniform coral red, a color both more intense and elegant.