11,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Atlantic Books

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

With its distinctive history of civil liberties and the delicate balance between social order and the free pursuit of self-interest, England has always fascinated its continental neighbours. Buruma examines the history of ideas of Englishness and what Europeans have admired (or loathed) in England across the centuries. Voltaire wondered why British laws could not be transplanted into France, or even to Serbia; Karl Marx thought the English were too stupid to start a revolution; Goethe worshipped Shakespeare; and the Kaiser was convinced that Britain was run by Jews. Combining the stories of European Anglophiles and Anglophobes with memories of his own Anglo-Dutch-German-Jewish family, this utterly original book illuminates the relationship between Britain and Europe, revealing how Englishness - and others' views of it - have shaped modern European history.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Ähnliche

About the Author

Ian Buruma is the Henry R. Luce Professor of Human Rights and Journalism at Bard College in New York state. His previous books include God’s Dust, A Japanese Mirror, The Missionary and the Libertine, Playing the Game, The Wages of Guilt, Bad Elements, Murder in Amsterdam – which won a Los Angeles Times Book Prize for the Best Current Interest Book and was shortlisted for the Samuel Johnson Prize – and The China Lover. He was the recipient of the 2008 Shorenstein Journalism Award, which honoured him for his distinguished body of work, and the 2008 Erasmus Prize.

Praise for A Japanese Mirror:

‘Buruma’s informed and perceptive study not only tells us a good deal about the matriarchs, warriors and geishas, whores and hoodlums of Japanese fact and fiction, but also identifies the deeply rooted erotic, violent and sadomasochistic fantasies which lie just beneath the surface of an exceptionally ordered society.’ Evening Standard

‘A brilliantly funny book about the bizarre pop-culture phenomena of modern Japan, from its absurdly violent mass-circulation porno-comics to its sentimental movies about gangsters and vagabonds.’ New York Times

‘Audacious, compelling and entirely readable … A Japanese Mirror, with its rich and sexy anecdotage, is an engaging, at times disturbing read, not least because its author, having derived his framework from the gods, knows when to pull the screen.’ New Statesman

Also by Ian Buruma

Bad Elements:

Chinese Rebels from Los Angeles to Beijing

The China Lover

Murder in Amsterdam:

The Death of Theo Van Gogh and the Limits of Tolerance

Conversations with John Schlesinger

Occidentalism:

A Secret History of Anti-Westernism

Inventing Japan:

From Empire to Economic Miracle 1853–1964

The Missionary and the Libertine:

Love and War in East and West

Wages of Guilt:

Memories of War in Japan and Germany

A Japanese Mirror:

Heroes and Villains of Japanese Culture

Playing the Game

God’s Dust: A Modern Asian Journey

The Japanese Tattoo

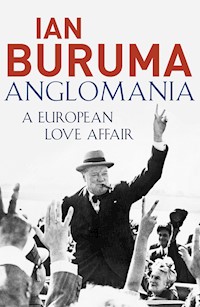

Anglomania

A European Love Affair

Ian Buruma

ATLANTIC BOOKS

London

Copyright page

First published in Great Britain under the title Voltaire’s Coconuts: or Anglomania in Europe in hardback in 1998 by Weidenfeld and Nicolson and in paperback in 1999 by Phoenix, an imprint of Orion Books Ltd.

This paperback edition published in Great Britain in 2010 by Atlantic Books, an imprint of Grove Atlantic Ltd.

Copyright © Ian Buruma, 1998

The moral right of Ian Buruma to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Acts of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

Every effort has been made to trace or contact all copyright holders. The publishers will be pleased to make good any omissions or rectify any mistakes brought to their attention at the earliest opportunity.

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN: 978 184 354961 1

Printed in Great Britain

Atlantic Books

An imprint of Grove Atlantic Ltd

Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London

WC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

Dedication

To Ann Buruma

and

G. M. Tamas

Contents

Acknowledgments

1 Churchill’s Cigar

2 Voltaire’s Coconuts

3 Goethe’s Shakespeare

4 Fingal’s Cave

5 The Parkomane

6 Graveyard of the Revolution

7 Schooldays

8 A Sporting Man

9 Wagnerians

10 Jewish Cricket

11 The Anglomane Who Hated England

12 Leslie Howard

13 Dr. Pevsner

14 The Man in the Tweed Coat

15 The Last Englishman

Sources

Bibliography

Index

Acknowledgments

Many people helped and inspired me during the writing of this book. There are several in particular to whom I would like to offer my special thanks. Conversations with John Ryle, Noel Malcolm, Ann Buruma, Graham Snow, Timothy Garton-Ash, Richard Nations, and Michael Ignatieff were invaluable in sharpening what began as a vague idea. Historical research was deepened and enriched by Michael Raeburn, Susie Harries, and Eva Neurath. Leo van Maris pointed me in the direction of valuable sources. Nicholas Philipson, Ian Jack, and Tom Nairn offered insights into Scottophilia. Ian Sutton and Emily Lane kindly shared their memories of Nikolaus Pevsner with me, as did Pevsner’s son and daughter, Dieter and Uta. Walter Blue and Lore Vajifdar helped me with my chapter on the refugee children. Michael Ignatieff, James Fenton, Leon Wieseltier, Stephen Beller, and Ann Buruma read various parts of the manuscript. Noga Arikha went through the final draft of the book with warm sympathy and a sharp eye. I could not have wished for better and more patient copy editors than Peter James and Martha Schwartz, a keener editor than Jason Epstein and his assistant, Ulf Buchholz, and more supportive agents than Andrew Wylie, Sarah Chalfant, and Jin Auh of the Wylie Agency. But even with the help and encouragement of all these people, I would have had a hard time finishing any task without the loving support of Sumie, my wife.

1 Churchill’s Cigar

It was in 1960, or possibly 1961, at any rate before the first Beatles LP, that I went shopping for cheroots with my grandfather. He was over in The Hague on a visit from England. I was about ten. I was born in The Hague. My father was Dutch and my mother English. To me a visit to Holland by my grandparents felt like the arrival of messengers from a wider, more glamorous world.

My grandfather, who had served as an army doctor in India during the war, liked Burmese cheroots. These were hard to come by in Holland, but if there was one shop in The Hague that was likely to stock them, it was a tobacconist named de Graaff.

G. de Graaff was an old-fashioned family firm. A portrait of the founder, a man with elaborate whiskers and a stiff white collar, hung on the wall behind the counter. We were served by the founder’s grandson, a small, dapper man in a three-piece suit, with the slightly fussy manners of an old-fashioned maître d’. He opened some boxes of cigars for my grandfather to sample. One or two specimens were taken out, to be pinched and sniffed. A purchase was made. I don’t know whether they were Burmese cheroots. But I can remember vividly the look on the tobacconist’s face when he realized my grandfather was an Englishman.

De Graaff said he had something special to show. He smiled in anticipation of my grandfather’s pleasure. “Please,” he said, and pointed at the wall, where Cuban cigars were stacked. And there, in an open space, between pungent boxes of Coronas and Ideales, hung a framed glass case containing two long, cinnamon-colored cigars, dry as old turds; one had been partly smoked, the other was untouched. The case had been sealed with red wax. At the bottom was a copper plate bearing the simple inscription 1946, sir winston churchill’s cigar.

I found out more about the famous cigar on my second visit to the shop, almost forty years later. The old de Graaff was dead. His son, a tall man with a somewhat ostentatious gray mustache, showed me the glass case, the two cigars, and a letter from Queen Wilhelmina’s court marshal, in which de Graaff was thanked for his supply of fine cigars. They had been presented at the queen’s lunch for Winston Churchill. One of the cigars had been lit by Churchill himself and passed through his very own lips. The other came from the same box. The partly smoked cigar had been put away because lunch was served and the queen couldn’t abide smoking in her presence. However, the two precious relics were saved for posterity by Churchill’s butler, who passed them on to one of the queen’s footmen, who presented them to de Graaff, who then had his solicitor draw up the document to vouch for their authenticity.

My grandfather would have been amused and, being a patriot, probably touched by this gesture. Then again, in those days he might have been accustomed to such small tributes being paid to being British. Through the late 1940s and 1950s, and even in the 1960s, the British were considered a superior breed in places like The Hague. For the British, together with the Americans and the Canadians, had won the war. So had the Soviet Union, but the Red Army was never anywhere near The Hague, and besides, the Red Army was, after all, the Red Army.

The British are no longer regarded as a superior breed, even in The Hague. The image of Britain as the land of war heroes is disappearing. Now when the British return to wage war in Europe, they come as soccer hooligans: history repeating itself as a beer-flecked horror show. But I still grew up with the image of British superiority, which gave me vicarious pleasure as well as the kind of slight resentment one might feel toward a very grand parent. It was an image that owed a great deal to snobbery, but to something else, too, something more political in origin: a particular idea of freedom. The characters in this book—Europeans who loved or hated Britain—were either attracted by the ideal of British liberty or disgusted by it. Since I am one of my own characters, and the one I probably know best, I shall start with my own account, about growing up in The Hague, and about my grandfather, whom I worshiped with the intensity of which only little boys and religious fanatics are capable.

My grandfather, Bernard Schlesinger, was the son of a German-Jewish immigrant, which explains, perhaps, his particular brand of patriotism. I would watch him as a child, during the summer holidays, as he worked in his Berkshire garden, picking vegetables or pruning the fruit trees, dressed in corduroys and tweeds. Even though he was in fact a pediatrician in London, he seemed to belong to the landscape: the fields, smelling of hay; the villages, smelling of horse dung and smoke; and the large Victorian vicarage that my grandparents bought after the war, smelling of candle wax and polished oak. This was his home. He would talk to me about the importance of loving one’s country, and how he loved England. I did not understand the depth or the nature of his love. I was never unhappy in Holland, but from quite an early age it was a place I always thought of leaving. The world seemed more promising elsewhere (a state of mind that, once entered, will never leave you in peace). But to my grandfather, England was not only the country he was born and raised in; after Hitler, it was, in his mind, the country that saved him, and his family, from almost certain death.

To be saved. Can the feeling of liberation ever be transmitted to those who have always been free? My father, who was forced to work in a German factory during the war, was liberated in Berlin by the Soviet Red Army. His memories of freedom regained are set to the sound of Russian dances and Ukrainian folk songs (after the Stalin Organs and the Flying Fortresses). But his case was unusual. For most Dutch people, freedom came from the West. As a child I read stories of the so-called Engelandvaarders, the men who sailed for England, in yachts, dinghies, even rowboats, anything that would float across the North Sea, to freedom. In the stories—though not in real life—they invariably made it and came back as heroes in Spitfires. Our ideas of England, or America, or Canada, were inseparable from the idea—rather abstract, to us—of freedom.

It is impossible to imagine quite what it must have felt like: the erotic rush of being freed. In the Netherlands, and elsewhere in Europe, the sexuality of liberation was not only subliminal; it was blatantly, frenetically acted out. Local men were pale and skinny from years of hiding, fear, and malnutrition. The sight of smiling GIs, lolling on the back of their jeeps, smoking Lucky Strikes and chewing gum, cannot have offered a greater contrast to the more familiar sight of marching German soldiers, stamping their boots and bellowing songs in perfectly drilled formations. Americans and Canadians, well fed, smartly turned out, and tanned from the Italian sunshine, liberated Holland to the swinging beat of Glenn Miller’s “In the Mood.” The British Tommies were perhaps weedier, knobblier, shorter. They carried less cash and could not show quite such immaculate teeth when they smiled their victory smiles. But the girls still adored them.

The summer of 1945 turned into an orgiastic celebration of liberty. At least seven thousand illegitimate children were spawned in one month in Holland alone. Everywhere, at street parties, in schools, in cafés and restaurants, there was the sound of swing and the smell of perfume, sweat, and beer. And sex: in short-time hotels, in rented rooms, in parks and abandoned houses, in jeeps, at dance halls, cinemas, and up against the walls of provincial back streets. Not until 1964, when girls jumped into the canals to touch the pleasure boat that bore the Beatles through Amsterdam’s canals like conquering heroes was anything like it seen again.

It seems so long ago, that summer of 1945, which to me is not even memory but history. And not even history per se, but movie history. In my mind’s eye, the liberators of ’44 and ’45 are not those anonymous men kissing girls on tanks in black-and-white photographs, but John Wayne, Kenneth More, Richard Burton, and Robert Mitchum landing at Normandy. I still weep at the scene in The Longest Day when the Frenchman, played by Bourvil, in his carefully preserved World War I helmet, waves a champagne bottle, like a madman, at the British and American troops who rush past him. “Welcome, boys!” he shouts. The soldiers laugh but have no time to stop. They are amused, but they fail to see the pathos of the situation; they cannot feel what he does. He is the one being freed. In the end, he is left on his own, in the rubble of his town demolished by artillery and bombs, still cradling his bottle of champagne, with no one there to share it.

When I stood in the center of Amsterdam, exactly fifty years after liberation, watching the British and Canadian jeeps pass by once more, perhaps for the last time, in celebration of Liberation Day, I had a whiff of what it must have been like back then. It was hot. The streets were packed. There was music: Glenn Miller on the square in front of the royal palace; Vera Lynn somewhere near the hot dog stands behind the Krasnapolsky Hotel. Young people danced to a rock and roll band, and over by the station somebody was playing “Hail the Conquering Heroes Come.”

It was a sentimental, anachronistic reconstruction. How could I know what it had really been like? I wasn’t hungry, for one thing. Yet it was impossible not to be moved as the jeeps rolled slowly down the Damrak toward the royal palace. Elderly Canadian and British veterans, dressed in uniforms that no longer fit, tried to keep their lips from trembling as men and women, especially women, along the route surged forward to touch their hands, the way they did fifty years ago, shouting, “Thank you! Thank you!” For a few hours, old men, whose stories had long worn out the patience of the people back home, were heroes again in the country they had liberated.

It is one of the great differences between Britain and the western seaboard of Europe, this divide between those who remember being freed and those who did the freeing. Since these experiences have passed into history, the actual memories have dimmed, but the divide remains. It is there, like a shadow, clouding every British debate on “Europe”: Britain is free, Europe must be liberated or left to its own devices. It is disturbing to hear British nationalists ranting against “Europe” by invoking Churchill’s war, precisely because I, and others of my generation, still respond to such rhetoric so easily. But to see the rhetoric of freedom as simply a product of Dunkirk nostalgia is to miss an important point. The idea of British freedom under threat from Continental tyranny goes back centuries. And it is not entirely spurious.

Britain has been a haven for refugees from many purges and tyrannies: Huguenots in the seventeenth century, aristocrats after the French Revolution, revolutionaries after 1848, Jews in the nineteenth century and again in the 1930s. This idea of freedom—not egalitarianism or fraternity—is what has drawn people to the United States as well. And there are similarities between Anglo- and Americophilia. The French often lump les anglo-saxons together as a composite model of economic laissez-faire and shallow materialism. The idea of a special Anglo-American bond still has a sentimental appeal in Britain and among the eastern upper classes of America. And yet there is also a great divide in the camp of the liberators.

It was visible in June 1994, when the D-Day landings were remembered in Normandy. Veterans from many countries marched on the beaches, stiffly, proudly, aware that this might be their last reunion. Bands played; people cheered; neat rows of soldiers, buried in the war cemeteries, were thanked by public figures for having “laid down their lives” for freedom. Representatives from all the main Allied powers spoke. But I was struck, watching the proceedings on television, by the differences in style.

The United States was represented by its elected head of state. But President Clinton was too young to remember D-Day. And on this occasion the veterans’ speeches carried more weight. They were elderly now, bald, white-haired, portly men, dressed casually in T-shirts and baseball caps. They did not stand stiffly to attention. These were the men who had lolled on the back of their jeeps, smoking Lucky Strikes, as they rode into the arms of thousands of girls in Paris, Brussels, and Amsterdam. Their speeches were not flowery, or poetic, or even very eloquent, but they spoke of liberty without a hint of old-world cynicism. They believed in it, and this gave them a dignity that no amount of pomp could contrive.

In British ceremonies and commemorations, the tone was set by royalty, nobility, and the clergy, dressed up in traditional finery. The duke of Edinburgh spoke about freedom and survival, and the veterans, wearing their wartime decorations, saluted the duke with quivering hands. They marched past the queen and saluted her too. Archbishops delivered sermons, and the chaplain-general carried out his duty with solemn grace. BBC reporters told their viewers in hushed tones “how well we still do these things.” There is indeed a certain poetry in British pomp and something grand about the pride in continuity and the belief in tradition—even if the tradition is often not as old as it pretends to be. The ancien régime of Britain survived, heroically, while America liberated the world, or at least large parts of it.

No doubt many people, including Americans, would have found the British talk of freedom and the deference paid to social rank contradictory. Many British people, especially those on the left, would too. But not British conservatives, and not a certain kind of Anglophile. For they would argue that freedom and democracy are safeguarded by deference and tradition—vox pop tempered by enlightened aristocracy. That was the Britain Winston Churchill stood for. It is the reason why a snobbish tobacconist in The Hague was so proud to own a stub of the great Englishman’s cigar. If freedom is one component of Anglophilia, snobbery is another.

The Hague always was a snobbish town. As with many snobbish towns, there is not a great deal to be snobbish about. The criminal underworld is large and brutal. The people are not especially friendly, and the local patois is rough and charmless. But The Hague is the official residence of the royal House of Orange. The government is there, and so are the embassies. From the seventeenth until the late nineteenth century, the town had a certain cosmopolitan elegance, with a fine municipal theater built in the French style, and several good concert halls. Mozart played there as a child prodigy. Voltaire spent time in The Hague. The leafy center, near the medieval parliament building, was a place for fin-de-siècle flâneurs to be seen, strolling among the trees of the Lange Voorhout, on their way to the Hotel des Indes, where Anna Pavlova, the ballerina, died in her suite in 1931. (Round the corner lived Mata Hari, who entertained her gentleman friends at the same hotel.)

The Hague was a smallish town with aspirations to a grand style. This style was inspired by (when not a direct imitation of) foreign manners and fashions. The architecture of Louis XIV was copied at the end of the seventeenth century. Two hundred years later, and in some cases long after that, smart people still spoke French at home. Adopting the manners of a foreign elite is a way for local society to feel distinguished. Since Amsterdam was the only real city in Holland and Rotterdam the center of commerce, a grand style was essential for The Hague to dress itself up as being something more than a provincial capital. This lends to parts of The Hague a peculiar staginess: the perfect setting for people who like official decorations, protocol, and the subtleties of placement at diplomatic dinner parties.

There were still remnants of the grand manner when I grew up in The Hague. Upper-middle-class matrons would insist on pronouncing certain Dutch words à la française. Old colonials from the Dutch East Indies—most of whom settled in The Hague—would dress up in tropical suits and order rijsttafels at old-fashioned restaurants as though they were still at the club in Batavia. And gossip was still exchanged in drawing rooms around the Lange Voorhout, or an area known as Benoordehout, literally “North of the Woods,” about this ambassador or that. But the predominant style among “Our Kind of People” (Ons Soort Mensen, or O.S.M.) had become English instead of French.

North America was respected for its wealth and power, but Britain held a singular fascination for the snobs, that is to say, much of The Hague’s elite. Churchill’s Britain had fought off a Continental tyranny to preserve its liberal institutions. But something else had survived in Britain, or perhaps I should say England, something Shakespeare called degree and we call class. Class distinctions exist everywhere in Europe, but after World War II there were few traces left of an ancien régime, even in the Continental monarchies, no aristocratic upper houses, no great landowning dynasties. Some of the names had survived, but they played no significant part in public life. What was unique, and therefore so fascinating about England, was not the mere survival of aristocracy but the survival of an aristocratic style aspired to and imitated by the upper middle class.

Elements of the Dutch bourgeoisie, perhaps more than was later admitted, were attracted before the war to the German idea of a Nordic Herrenvolk, as indeed were some English aristocrats. North of the Woods Anglophilia might be superficially related to this. But I don’t think so. What the Anglophiles admired was not so much aristocracy, let alone a racial elite, but something both more liberal and more bourgeois than that: the gentleman, whom André Malraux once called England’s grande création de l’homme. A bourgeois man with aristocratic manners, a tolerant elitist who believes in fair play: the image of the English gentleman, bred rather than born, appeals to snobbery and liberalism in equal measure. North of the Woods bristled with would be English gentlemen.

North of the Woods is not a grand place. There are no particularly grand houses. It is much like those English suburbs mocked in Bateman cartoons. I associate the summers of my childhood with the monotonous swish-swish of garden sprinklers and the smell of freshly cut grass. Winter or summer, the streets always looked immaculate and dull. But there, mowing those lawns and working those sprinklers, were the doctors, dentists, lawyers, and bankers in their blue blazers, English brogues, and club ties: the Anglophiles. Grown men would sit in the wooden pavilion of The Hague Cricket Club with transistor radios pressed to their ears, following the latest Test Match results in England. “Cowdrey’s out!” one would shout, or “Trueman’s got a wicket!” All this exclaimed in Dutch, but with the drawl of North of the Woods gentility. It is a sound easier to imitate than to describe on paper: something between a goose’s honk and a duck’s quack.

The Anglophiles took the badges of their peculiar identity seriously. They were almost fetishistic about them. It is possible to write a study on the significance of the club tie alone. The yellow and black cotton HCC tie was readily available at designated sports shops. But there was more prestige in wearing the yellow and black tie of Clare College, Cambridge, which was made of silk and had to be bought in England. Anyone traveling to England would get so many requests to purchase this item at a special club tie shop in Margaret Street, London W1, that he would come back laden with neckwear, like a traveling salesman.

Brogues were another sartorial fetish. Many shoe manufacturers made these shoes with ornamental holes, originally designed to let water drain out when one went sloshing through Scottish peat bogs in the rain. But not every kind of brogue would do. Only the classic English brogue was acceptable. Oddly, other types of English shoes, more popular in England, were not. The elastic-sided Chelsea boot, for example, was considered too eccentric. A young HCC cricketer once came back from England with a pair of suede Chelsea boots. No matter how he tried to convince his friends that these were absolutely fine in England, in their eyes they still looked ludicrous.

The English style was never adopted wholesale. Authenticity was not the point. I was an oddity as a boy in The Hague because my mother liked to dress me up in long flannel shorts and knee socks, like an English schoolboy. Authenticity, divorced from its context, is absurd. To my peers, my Marks and Spencer outfits made me look like Little Lord Fauntleroy. When I was at secondary school, in the middle 1960s, the fashion in North of the Woods was to wear imported British college scarves with colored stripes. I had one of those, with black and yellow Clare College colors, worn wrapped around my neck with studied nonchalance. But then my grandmother bought me a double-breasted overcoat at a school outfitters in London. This was a step too far. It was the sort of coat only elderly bankers might have worn in Holland, before the war.

Anglophilia is of course a fantasy, like all forms of “philia,” which can easily degenerate into a form of pretending to be something you are not. My view of England was no less fantastic than that of my friends at the HCC, but it was fed by knowledge they didn’t have, by Boy’s Own annuals and comics about British schoolboys winning football matches and British heroes winning the war, killing cartoon Germans who were all named Fritz. I consumed British fantasies about Britain, without being British. This caused a certain amount of confusion, more to do with nationality than with class. In my case, the fetishism of the club tie was infinitely expanded: I made a fetish of nationhood itself. To be more English I would spend hours imitating my mother’s handwriting, as though something of the effortless English superiority, something of my grandfather’s Berkshire landscape, some vital if undefinable essence of Englishness would rub off.

But what was my grandfather’s landscape, this English way of life glimpsed during school holidays, which seemed so much more glamorous and desirable to me than our perfectly good life in The Hague? My grandparents’ house: I still go there sometimes to look at what is left of it. I park my car furtively in the drive and gaze at the old Victorian vicarage, so white, so large, so warm in my memory, and so remote now. It has had several different owners since my grandparents sold it, and several coats of paint. The color changed from white to gray, and back to white again. It seems to have shrunk since I was there as a boy. Details have been fixed. The gardener’s cottage is now a weekend house with glazed windows. The chicken coops, where I used to collect eggs, are gone. And the garden that seemed to stretch for miles up to “the fields,” where cows grazed beyond a row of beech trees, looks smaller, more fenced in, than the way I remember it. The M4 cuts through the fields now. You can hear and see the traffic rushing past a petrol station and “service center” built on the old runway of a wartime aerodrome, which, when I first saw it, was already over-grown with weeds.

Impressions come flooding back, which, when I think about them, seem too quaint, too stereotypical, too Merchant Ivory, to have been true: people drinking sherry on the terrace; village fêtes on the lawn; my grandmother, in brown gardening shoes caked with fresh mud, carrying hampers filled with vegetables; cooked breakfasts kept warm under silver covers; The News of the World and the smell of stale sweat and cigarettes in the cook’s tiny backstairs room; cavernous linen cupboards; a larder smelling of cheese and butter; picture books of Lancaster bombers, left behind by uncles who were children during the war; the crunching sound of cars rolling up the drive. When the sun wasn’t shining, it was snowing. It was never simply dreary. For it was a childhood idyll that memory has turned into a vision of Arcadia, like a sentimental Christmas card.

And it was there, in that Arcadian house, that I first realized that foreigners were funny. Our name was funny, our accents were funny. Amongst ourselves, my sisters and I spoke Dutch, which was particularly funny. I also concluded another thing, not entirely unrelated to the funniness of foreigners, something that was never openly stated, at least not by my own family, or at least not until my grandfather’s mind started wandering and his opinions coarsened. It was something I could not but conclude from the huge lawns, three-course breakfasts, four-course lunches, daily high teas, and stacks of presents at Christmas: the absolute superiority of life in England.

There was, however, something unusual about this childhood Arcadia. My grandparents were both children of German immigrants. Their parents had once been foreigners too. The very English life I observed at the house in Berkshire had been the result of conscious decisions, considerable effort, and a kind of stoicism. My great-grandparents decided to give their children the most English education available. My grandparents had broken out of a narrow Jewish émigré community in North London. And they had been stoical when others chose to see them as being less British than they did themselves. My own Arcadian view of England was linked to these decisions and these efforts, for I learned to look at England largely through my grandparents’ eyes.

This was not something my fellow North of the Woods Anglophiles could share. Their concern was, as I said, class snobbery, to which I myself was by no means immune. I sat up on the balcony of the cricket club pavilion with the other boys, calling out “rug merchant,” before withdrawing our heads like turtles, whenever Mr. W. walked by in his cavalry twill trousers and his Clare College tie, with a copy of The Daily Telegraph rolled up in the pocket of his immaculate blue blazer. Mr. W. was a handsome man with dark shimmering hair. He was perhaps a little overgroomed, a little louche even, with a fondness for hair oil and tinted glasses. His older wife was a large and over-dressed woman who had inherited several grand hotels. The rumor got around, even to us younger boys, that Mrs. W. had married her husband for his looks, and that before his turn of fortune Mr. W. had been in charge of laying the carpets in one of her hotels. We sniggered at the rolled-up English newspaper, which he never appeared to read. We sneered at his lounge lizard hairdo. We mimicked his accent, which, to our exacting ears, was a touch off. The sin of Mr. W. was not that he lacked Englishness, despite all the trappings, so painstakingly assembled. His sin was that he lacked class.

We were much more forgiving toward real Englishmen. Members of visiting English cricket teams rarely lived up to the idealized image of the English gentleman. They were Rotarians from the Midlands, car dealers from Kent, or policemen from the outer suburbs of London. Few, if any, matched their hosts in the blazer and brogues department. There might have been the odd club tie, but that was it. And if they didn’t look like David Niven, they didn’t speak like him either. But this did not really matter. British guests were not expected to live up to the semiotics of Dutch class divisions.

Then came the sixties. The English club tie began to lose some of its magic as the decade unfolded, even North of the Woods, but for the younger generation the glamour of Britain got a boost from the Beatles, the Who, and the Rolling Stones. For the second time in twenty years liberation came from the West. It was as though Glenn Miller and Lucky Strikes hit Europe once again, this time with a louder beat. But the second wave of Anglo-American liberation was different. What gave British youth culture its zest was the rude working-class challenge to middle-class boredom and complacency. Such emblems of British respectability as the national flag, the King’s English, old school ties, brogues, or having enjoyed a “good war” were treated as jokes. These signals were not always picked up accurately on the European Continent, but we heard the beat and knew something exciting was going on. Instead of coming back from holidays in England wearing college scarves and gabardine coats, I now sported a powder blue Beatles hat from the King’s Road.

British working-class heroes have their own peculiar attractions. In a way, Britain was the only western European country that still had a true working class, with its own class traditions and culture, in which it took pride. This, too, was part of the ancien régime. While revising this chapter, I had tea with a German-born British peer. We were sitting in the tearoom of the House of Lords, me in my jacket and tie, he in his pin-striped suit (Gieves & Hawkes, Number 1 Savile Row). He had had a distinguished career as a German social democrat before deciding to become an Englishman. He had been a classic liberal Anglophile. “Well, well,” he said, “well, well …,” and he took a sip from his cup of tea. There was a look of deep sadness on his face as he gazed on the gray gloom of the Thames outside. “What one admired about this country,” he said in his soft German accent, “was the aristocracy and the working class. Now that Britain has become a middle-class nation, it’s no longer any different from anywhere else in Europe.” He sighed, resigned to his melancholy. “Well, well,” he said, “well, well.”

What attracted Europeans of my generation, however, was not the culture of miners’ brass bands, trade unions, or cheery pub songs; it was the culture of rebellion. Perhaps there was a tenuous link between this—pop music and rebellious attitudes—and earlier forms of Anglophilia, rooted in the revolt against absolute monarchy. There was even a link with aristocracy. While imitating American rock and roll, many British pop groups expressed an aching nostalgia for a pre-American England, an Edwardian or even Regency England of music halls and dandies, striped blazers and Crimean War uniforms. The past was treated with irony but with a melancholy longing too, for a kind of aristocratic hedonism. It was as though a generation of working-class children had raided a vast stately home and dressed up in the master’s old clothes. When British pop stars struck it rich, many of them bought stately homes and lived like stoned lords and ladies. This gave them a sense of style that had no Continental parallel, for we had no ancien régime. It was theatrical, nostalgic, ironic, exciting, and intensely commercial.

Perhaps that’s why Anglophilia thrives in seaports and trading places, such as Hamburg, Lisbon, Milan, and cities on the Dutch coast. When merchants get snooty, they become Anglophiles. There was no more snobbish, more Anglophile city than prewar Hamburg, with its yacht clubs, horse racing, and quasi-rural suburbs. Wealthy shipowners continued to send their sons, named “Teddy” or “Mickey” or “Bobby,” to British boarding schools well into the 1930s. They were hurt and bewildered when British bombers destroyed much of their city in one moonlit night in 1943. But to say that Hamburg Anglophiles were snobbish is not to say they were reactionary. On the contrary, like most seaports, “the Free and Hanseatic City of Hamburg” has a long liberal tradition. Merchants can’t afford to be reactionary. Their snobbery is a sign of social mobility, of acquired airs and graces, not of birthright or noble privilege.

The Hague was never a city of traders. But it became known as “the mightiest village in Europe” during the seventeenth century, when it was the capital of the Dutch Republic, a maritime trading power facing Britain as its main partner and rival. The Hague would never be mightier than during that Dutch Golden Age. Hugo Grotius developed his doctrine of freedom of the seas there. Forbidden books from France and elsewhere were published there. But things began to slide in the eighteenth century. The lowest point for The Hague, and the entire western province of Holland, was when Napoleon enforced the Continental System, which outlawed trade with Britain. Well, perhaps not quite the lowest point.

A few years ago I came across a curious book in a secondhand bookshop in Amsterdam. It was a German book entitled Face of the Netherlands, published in Berlin in 1943 and written by one SS Obersturmführer Ernst Leutheusser. This fascinating document, illustrated with pretty black-and-white photographs of churches, canals, cheese markets, blond children in regional dress, and industrious farmers with stern “Nordic” faces, was a kind of guidebook for SS officers posted in the occupied Netherlands. The picture of Holland is by no means hostile; on the contrary, the author emphasizes the fraternal relationship between two Nordic peoples. The historical nature of that relationship is explained by the SS Obersturmführer.

There are really two parts of the Netherlands, he says. There is the authentic, eastern half of the country, largely agricultural, facing Germany and populated by people of good Saxon stock who feel they are part of Europe. (Europe is, so to speak, in their blood.) Then there is the western seaboard with its cities, dominated by merchants, looking toward Britain and the oceans beyond for opportunities to enrich themselves through trade. This is the “deracinated” half of Holland, dependent on “Britain and other anti-European powers.” The western merchants and patricians have turned against their European roots. Regrettably, their “materialistic, bourgeois-capitalist mentality” has infected the rest of the country, resulting in its increasing “alienation from Europe.” But we should rest assured, for under the benevolent tutelage of the Third Reich, this would all soon be put right.

I was strangely moved by this book, for here, in the words of the enemy, was a description of the Europe I consider my home. It stretches from the Baltic states, via northern Germany and Denmark, all the way down the Atlantic coast to Lisbon. One might call it an Anglophile Europe. It consists of great cities populated by bourgeois capitalists who like to trade freely with others, whatever their race or creed. It is from this part of Europe that expeditions went out to discover the world and build empires, for better and for worse. It is also here that liberal politics and ideas thrived. And they thrived more continuously in Britain than anywhere else.

So even though Anglophilia is often no more than a tiresome social affectation, it can be something nobler than that. For about three hundred years, since the Glorious Revolution, Britain attracted liberals from all over Europe, including Russia, because of its remarkable combination of civility and freedom. It was also a society of great social and economic inequality, cruel penal codes, cultural philistinism, barbarous mobs, and insular attitudes to the outside world. But for long periods it was the only major European power that had a free press, freedom of speech, and a freely elected government.

And yet European Anglophilia is not what it once was. The United States has replaced Britain as a great power. People who would have admired Britain in the past now often look to America for inspiration. And those who would have hated Britain for its commercialism, its individualism, and its tolerance of inequality will hate America today. But there is another reason for Britain’s loss of standing on the European continent. Seen from the rest of Europe, post-imperial Britain often appears to have retreated into an insular sulk.

When I came to live in England in 1990, for the third time in my life, I noticed a mood of fretful introspection. “Englishness” had become a subject of endless discussion not only at university seminars but in the popular press. Fox hunting was a topic of debate, not just about the pros and cons of killing for sport but about hunting as an irreplaceable (or reprehensible) badge of “Englishness.” Loyalty to the England cricket team was another hot issue, thrown up by a Conservative politician who was oddly convinced that patriotism was a matter of skin pigment. And the future of the monarchy was seldom out of the news.

There was an anxious tone to much of this chatter, which I recognized. I had lived in Japan for some years. There, too, the matter of national uniqueness, of an essential, semimystical, ineffable “Japaneseness,” to be protected from socialists and American cultural imperialism, was discussed, dissected, and fretted over. In the English case, it was linked to the loosening bonds of the United Kingdom, but even more to the growing bonds with what was loosely termed “Europe.”

As in all discussions of national character, this worrying over Englishness usually results in great balls of intellectual wool. Englishness is a romantic not a political concept. There is nothing particularly wrong with this. It might even produce some good poems—though it is likely to produce many more bad ones. But the narrow defensiveness of much anti-European rhetoric often obscures the more practical reasons why many Europeans have admired Britain in the past.

I have chosen to reexamine some of those reasons from a European point of view or, rather, from a gallery of views. I have selected a number of European Anglophiles and, by way of contrast, some ferocious Anglophobes, to see what Europeans particularly admired (or loathed) about Britain and how much, if anything, of these virtues (or vices) has survived. The choice of characters might strike the reader as eccentric. Some are famous, others obscure. Some obvious candidates have been left out; Napoleon, for example. None of my Anglophiles loved Britain blindly (blinding passion is more a mark of the haters). Most of them, especially the more starry-eyed, saw their dreams tarnished in the end by a sense of disillusion—the necessary condition for recognizing something approximating the truth.

Since Anglophilia is often a matter of style, some of the examples in the following chapters might seem superficial, or frivolous. But frivolity can contain hidden depths. I have a Hungarian friend named G. M. Tamas. He is a professor of philosophy and a classic Anglophile. Like many central European Anglophiles, Tamas could not be less English in behavior or appearance—in spite of his white linen suits and Harris tweeds. He is a thin, dark, bearded man, intensely intellectual, garrulous, and excitable about culture and politics. Tamas is the kind of man you would expect to see at a café table in Budapest or Bucharest, manically arguing an abstruse philosophical point. He is a talker. He takes things seriously. He worries about the world, which is always on the brink of catastrophe.

Tamas was born in Cluj, Transylvania, where his grandfather was a cantor at the local synagogue. After moving to Budapest, he became a political dissident. Like many who suffered under communism, he admired Margaret Thatcher. Tamas paid the usual price for his dissent: isolation, arrests, spells in jail. After 1989, he became a liberal conservative politician. But he was soon disgusted with the political climate in his country, which he still regarded as a degenerate, antidemocratic madhouse. So he became a philosopher at large, roaming the world, talking incessantly about the Central European debacle, and dreaming of an English home.

In 1988, a year before the end of the Soviet Empire in Europe, Tamas wrote an article in The Spectator that contained an image that provided the kernel for this book. Like Churchill’s cigar, the Clare College tie, and the brown brogues, it concerns a fetish. It is the best, most concise expression I know of a timeless Anglophilia:

How to be a gentleman after 40 years of socialism? I recall the tweed-clad (Dunn & Co, 1926) and trembling elbow of Count Erno de Teleki (MA Cantab, 1927) in a pool of yoghurt in the Lacto-Bar, Jokai (Napoca) Street, Kolozsvar (Cluj), Transylvania, Rumania, 1973. His silver stubble, frayed and greasy tie, Albanian cigarette, implausible causerie. The smell of buttermilk and pickled green peppers. A drunk peasant being quietly sick on the floor. This was the first time I saw a tweed jacket.

2 Voltaire’s Coconuts

“By G——I do love the Ingles. G—d dammee, if I don’t love them better than the French by G——!”

—Voltaire

Why can’t the world be more like England? This is the question raised by Voltaire in the Philosophical Dictionary of 1756. It is a curious question to ask, especially for a Frenchman. But Voltaire first came to England in 1726, thirty-eight years after the Glorious Revolution and twenty-six years after the building of the Bevis Marks Synagogue in London (with money from a Quaker and wooden beams donated by Queen Anne). Having suffered a stint in the Bastille for publishing a satirical poem and unable to publish another poem on religious persecution in France, Voltaire saw England as a model of freedom and tolerance. That is why I will start my gallery of Anglophiles with him. Voltaire is the first or at least the most famous, most eloquent, most humorous, most outrageous, and often the most perceptive modern Anglophile.

So why can’t the world be more like England? In fact, Voltaire’s query was a bit more specific: Why can’t the laws that guarantee British liberties be adopted elsewhere? Of course, being a rationalist and a universalist, Voltaire had to assume that they could. But he anticipated the objections of less enlightened minds. They would say that you might as well ask why coconuts, which bear fruit in India, do not ripen in Rome. His answer? Well, that it took time for those coconuts to ripen in England too. There is no reason, he said, why they shouldn’t do well everywhere, even in Bosnia and Serbia. So let’s start planting them now.

You have to love Voltaire for this. It is liberal. It shows reason and good sense. It is wonderfully optimistic. And it is too glib. But then comes the Voltairean kicker at the end: “Oh, how great at present is the distance between an Englishman and a Bosnian!”

I was thinking about his coconuts while sitting in Voltaire’s old garden in Ferney, now called Ferney-Voltaire, just across the French border from Geneva. It was an open day at the château. I had just been inside Voltaire’s old bedroom. The walls were decorated with prints of his heroes: Isaac Newton, Milton, and George Washington. There was also a larger picture of Voltaire himself ascending to a kind of secular heaven, being greeted by angels, or muses, while his critics writhe in agony below, like sinners in hell.

Voltaire was proud of his garden. He thought it was an English garden. He often boasted of having introduced the English garden to France, along with Shakespeare’s plays and Newton’s scientific ideas. He wrote to an English friend, George Keate, that Lord Burlington himself would approve of the garden. “I am all in the English taste,” he wrote. “All is after nature,” for “I love liberty and hate symmetry.” He designed it himself. But in fact, the style, judging from old prints, and from what is still visible today, is too small, too neat, too formal, too fussy—in a word, too French—to be a truly English garden of the eighteenth century.

Yet it is not without charm, even today. It is formal yet quirky and allowed to run a little wild here and there. There is a splendid terrace, with a view of a round pond and a fountain. Straight gravel paths are lined with lime trees and poplars. Behind the house is a long path with a straight row of hornbeams growing on either side—the “longest row of hornbeams in Europe” according to a local tourist guide. It must have been near there that Voltaire tried to grow pineapples, which, alas, died in the cold European winter. His vegetable garden is still there, however. And so is his fish pond, now dry.

I sat in the old fish pond, waiting for a reading of Voltaire’s texts to begin. After a while, two actors, a dark-haired young man in jeans and a leather jacket and an elegant blond woman, climbed onto a wooden stage and began to read. The text was “Catechism of a Gardener,” Voltaire’s satire on nationalist prejudices published in the Philosophical Dictionary. The actor and actress read most of it in French, but when they found some passages unpronounceable, they giggled and continued in Serbo-Croat. They were Bosnians from Sarajevo.

Voltaire’s first impression of England was of its fine, sunny weather. He landed at Gravesend, at some time—we don’t know quite when—in the spring of 1726. “The sky,” he recalled, “was cloudless, as in the loveliest days of Southern France.” He wrote this at least a year later, and it may well be that the cloudless sky, as well as much else in Voltaire’s account of England, owed something to the writer’s imagination. The weather had to be fine; it matched Voltaire’s idea of England, as the land where the Enlightenment found its brightest expression.

Voltaire gazed at the Thames in Greenwich, with the sun casting jewels on the gently shimmering water. The white sails of merchant vessels stood out against the soft English greenness of the riverbanks. And look! There were the king and queen, “rowed upon the river in a gilded barge, preceded by boats full of musicians, and followed by a thousand little rowing-boats.” The oarsmen were dressed “as our pages were in old times, with trunk-hose, and little doublets ornamented with a large silver badge on the shoulder.” It was clear from their splendid appearance and “their plump condition” that these watermen “lived in freedom and in the midst of plenty.”

The French visitor then proceeded to a racecourse, where he was delighted by the spectacle of pretty young women, all of them “well made,” dressed in calicoes, galloping up and down on their horses with exquisite grace. While feasting on the beauty of Englishwomen, Voltaire met a group of jolly Englishmen, who welcomed him heartily and offered him drinks and made room for him to see the action. First Voltaire was reminded of the ancient games at Olympia, but no, “the vast size of the city of London soon made me blush for having dared to liken Elis to England.” His new friends told him that at that very moment a fight of gladiators was in progress in London, and Voltaire instantly believed himself to be not in Greece but “amongst the ancient Romans.”

He was not alone in this conceit. It had become fashionable among the English themselves to think of their country as the incarnation of the Roman republic, pure, simple, uncorrupted by imperial fripperies, a model of liberty and classical grace. Venice was another source of inspiration. The combination of trade, freedom, and the rule of a noble elite was irresistible to Whiggish aristocrats who saw merit in trade and championed individual liberty. They could not get enough of Canaletto’s paintings of Venice to hang on their walls. When the great Venetian came to London in 1746, he too envisioned the British capital as a modern Rome.

But after the sun went down, a darker side of paradise was revealed to Voltaire. In the evening, he was presented to ladies of the court. Thinking they would surely share his enthusiasm for the sunny scenes he had witnessed on the riverbank, he told them all about his day, only to be met with an agitated flutter of fans. The ladies looked away from the excitable Frenchman in disdain, breaking the silence only to cry out all at once “in slander of their neighbours.” Finally one lady felt compelled by common courtesy to explain to the foreigner that the young women he had admired so foolishly were maidservants, and the jolly young men mere apprentices on hired horses.

Finding this hard to believe, or perhaps not wishing to believe it, Voltaire went out the next morning to look for his companions of the previous day. He found them in a dingy coffeehouse in the City of London. They showed none of their former liveliness and good cheer, and all they said to Voltaire, before discussing the latest news of a woman who had been slashed by her lover with a razor, was that the wind blew from the east. Hoping to find more gaiety in higher circles, Voltaire set off for the palace, only to be told there too that the wind was in the east. And when the wind was in the east, said the court doctor, “people hung themselves by the dozen.”

Although Voltaire was enough of a realist to treat the drawbacks of English life with sardonic wit, his England remained on the whole a sunny place, for it was based on an idea. The core of the idea was liberty and reason. Since reason, in his view, was a universal value, England, to him, provided a universal model. This makes him the father of Anglophilia, even though the nature of European Anglophilia would change considerably, especially after the French Revolution. Voltaire truly wished the rest of the world to be more like England. Others, like Montesquieu, soon took up the same idea. And this at a time when the ton of the upper class in England was still firmly Francophile.

Voltaire’s idea of England was a caricature, to be sure. There is a line to be drawn, crooked, frequently distorted, often imaginary, but a line nonetheless, from Voltaire to Margaret Thatcher: Britain as the island of liberty, facing a dark, despotic Continent. As with all good caricatures, Voltaire’s idea was not without substance. Even as the British aristocracy was imitating the language, dress, and manners of the French court, eighteenth-century Britain was a freer, more tolerant place than France. The Glorious Revolution had produced a constitutional monarchy, while in France an absolute monarch had robbed French Protestants of their religious freedom. After the Edict of Nantes was revoked in 1685, more than eighty thousand French Protestants and dissenters moved to London. Some of them would meet at the Rainbow Coffee-house in Marylebone to discuss politics and religion. They read the books of Locke, Shaftesbury, and Newton. And news of their discoveries soon found its way back to France, where they inspired Voltaire and Montesquieu.

Voltaire became an Anglophile in about 1722. Before that he had been a gifted libertine on the make, a powdered rake with a taste for actresses and rich men’s wives. He liked to amuse old roués with satirical poems, and he annoyed the authorities enough with his sallies to be jailed at the Bastille. His first literary success—a sensation, in fact—was his play Oedipe, performed in 1718. At the age of twenty-four Voltaire was hailed as the heir of Corneille and called the Sophocles of France—comparisons he himself did nothing to discourage. Philippe d’Orléans, the French regent, gave him a gold medal. And so did King George I of England, after the British ambassador, the second earl of Stair, had called Voltaire “ye best poet maybe ever was in France.” (Not that the Hanover king would have understood this fine phrase; he didn’t speak English.)

Voltaire’s second literary success, which made him even more famous, could not be published legally in France. This time the poet aspired to wear Virgil’s mantle. La Henriade is an epic poem, modeled on the Aeneid, celebrating the glory of Henri IV. It was not the poetry that offended the French censors but the ideas it contained. Henri IV had fought a war of succession to the French throne as a protector of the Protestants. He was backed by Queen Elizabeth of England. Although he later converted to Roman Catholicism—unconvincingly some thought—Henri signed the Edict of Nantes in 1598, guaranteeing freedom of conscience, the very thing that was revoked a hundred years later. La Henriade was an argument for religious tolerance and an attack on the fanaticism of the Catholic church. Since Catholicism was the French state religion, and religious dissent outlawed, Voltaire’s poem was about as subversive a document as one could wish. It was first printed in The Hague, and later published under the counter in Rouen.

One of Voltaire’s greatest admirers at the time was Henry St. John Bolingbroke, a Tory aristocrat compelled to live in France after conspiring with the Catholic pretender to the English throne. Bolingbroke shared with Voltaire a taste for libertinage, brilliant conversation, and unorthodox religious views. Voltaire recorded in his notebook how London prostitutes rejoiced when Bolingbroke became minister of war under Queen Anne. His new salary was greedily discussed by the whores in St. James Park. “God bless us,” they cried, “five thousand pounds and all for us.” In exile, Bolingbroke married the marquise de Villette, a French widow twelve years older than himself, and tended to his garden park at La Source, a woody estate near Orléans, which he transformed in the English mode, with streams, grottoes, groves, and a hermitage.

Voltaire visited La Source in 1722, and was enchanted. Bolingbroke, he wrote in a letter to his friend Nicolas-Claude Thieriot, was an illustrious Englishman who combined the erudition of England with the politesse of France. This was typical of Voltaire’s Enlightenment Anglophilia. England was the land of thinkers, of rationalists, while France was the nation of fine manners. Much of what we know about Voltaire in those days comes from his letters to Thieriot. Receiving Voltaire’s letters and acting as his drum-beater was Thieriot’s main role in life. He was a literary flâneur and a permanent guest at various grand houses, where he would recite Voltaire’s works and solicit praise for the master. It was to Thieriot that Voltaire later wrote Letters concerning the English Nation, his bible of Anglomania.

Dangerous ideas that could not be expressed publicly in early